The four books of The Nature of Order constitute the ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth in a series of books which describe an entirely new attitude to architecture and building. The books are intended to provide a complete working alternative to our present ideas about architecture, building, and planning — an alternative which will, we hope, gradually replace current ideas and practices.

| Volume 1 | THE TIMELESS WAY OF BUILDING |

|---|---|

| Volume 2 | A PATTERN LANGUAGE |

| Volume 3 | THE OREGON EXPERIMENT |

| Volume 4 | THE LINZ CAFE |

| Volume 5 | THE PRODUCTION OF HOUSES |

| Volume 6 | A NEW THEORY OF URBAN DESIGN |

| Volume 7 | A FORESHADOWING OF 21ST CENTURY ART: |

| THE COLOR AND GEOMETRY OF VERY EARLY TURKISH CARPETS | |

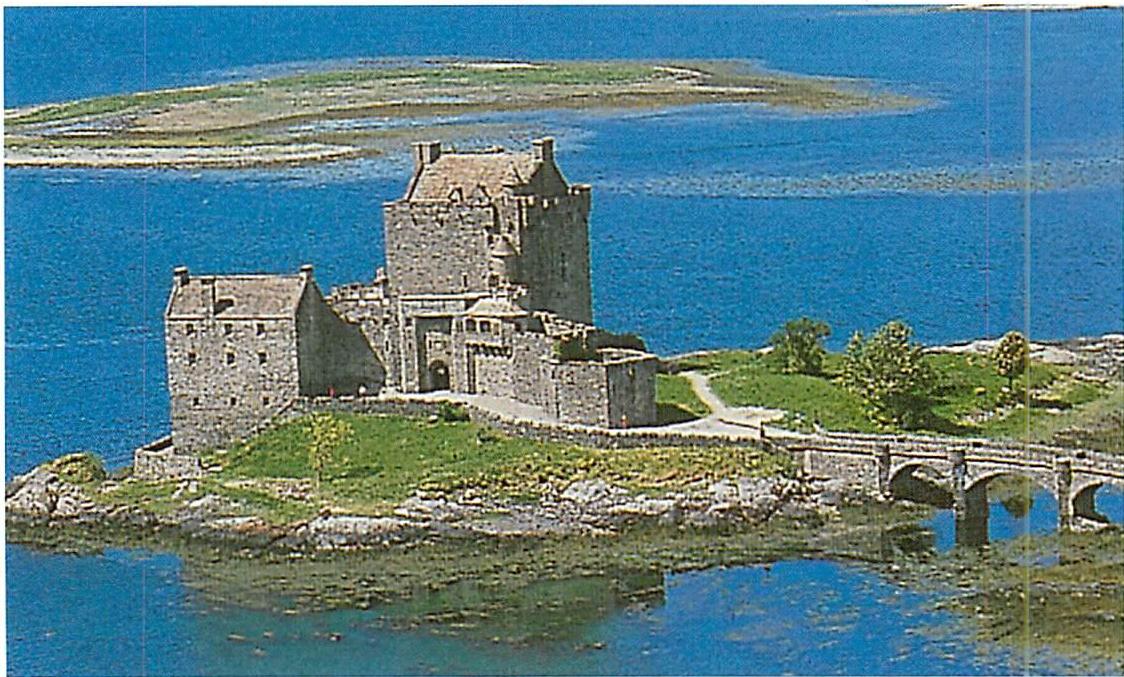

| Volume 8 | THE MARY ROSE MUSEUM |

| Volumes 9 to 12 | THE NATURE OF ORDER: AN ESSAY ON THE ART OF BUILDING |

| AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE | |

| Book 1 | THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE |

| Book 2 | THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE |

| Book 3 | A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD |

| Book 4 | THE LUMINOUS GROUND |

Future volume now in preparation

| Volume 13 | BATTLE: THE STORY OF A HISTORIC CLASH

BETWEEN WORLD SYSTEM A AND WORLD SYSTEM B | | --- | --- |

THE NATURE OF ORDER

An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe

BOOK ONE THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

BOOK TWO THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

BOOK THREE A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

BOOK FOUR THE LUMINOUS GROUND

THE CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL STRUCTURE in BERKELEY CALIFORNIA in association with PATTERNLANGUAGE.COM

© 2002 CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

PREVIOUS VERSIONS © 1980, 1983, 1987, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001 CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

Published by The Center for Environmental Structure 2701 Shasta Road, Berkeley, California 94708 CES is a trademark of the Center for Environmental Structure. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Center for Environmental Structure.

ISBN 0-9726529-2-2 (Book 2) ISBN 0-9726529-0-6 (Set)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Alexander, Christopher. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe / Christopher Alexander, p. cm. (Center for Environmental Structure Series; v. 9–12). Contents: v.1. The Phenomenon of Life — v.2. The Process of Creating Life v.3. A Vision of a Living World — v.4. The Luminous Ground

- Architecture—Philosophy. 2. Science—Philosophy. 3. Cosmology

- Geometry in Architecture. 5. Architecture—Case studies. 6. Community

- Process philosophy. 8. Color (Philosophy). I. Center for Environmental Structure. II. Title. III. Title: The Process of Creating Life. IV. Series: Center for Environmental Structure series ; v. 10.

NA2500 .A444 2002 720°.1—dc21 2002154265 ISBN 0-9726529-2-2 (cloth: alk. paper: v.2)

Typography by Katalin Bende and Richard Wilson Manufactured in China by Everbest Printing Co., Ltd.

BOOK ONE: THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

PROLOGUE TO BOOKS 1-4

THE ART OF BUILDING AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . 1

PREFACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

PART ONE

- THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

- DEGREES OF LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

- WHOLENESS AND THE THEORY OF CENTERS . . . . . . . . . 79

- HOW LIFE COMES FROM WHOLENESS . . . . . . . . . . . 109

- FIFTEEN FUNDAMENTAL PROPERTIES . . . . . . . . . . . 143

- THE FIFTEEN PROPERTIES IN NATURE . . . . . . . . . . . 243

PART TWO

- THE PERSONAL NATURE OF ORDER . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

- THE MIRROR OF THE SELF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 313

- BEYOND DESCARTES: A NEW FORM OF SCIENTIFIC OBSERVATION . . 351

- THE IMPACT OF LIVING STRUCTURE ON HUMAN LIFE . . . . . 371

- THE AWAKENING OF SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 403

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 441

APPENDICES: MATHEMATICAL ASPECTS OF WHOLENESS AND LIVING STRUCTURE . . 445

BOOK TWO: THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

PREFACE: ON PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

PART ONE: STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS

- THE PRINCIPLE OF UNFOLDING WHOLENESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

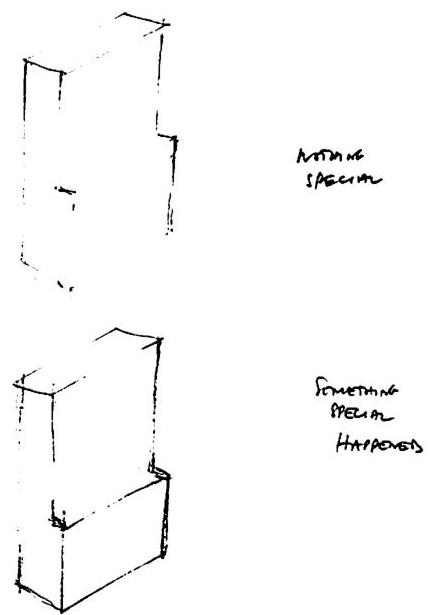

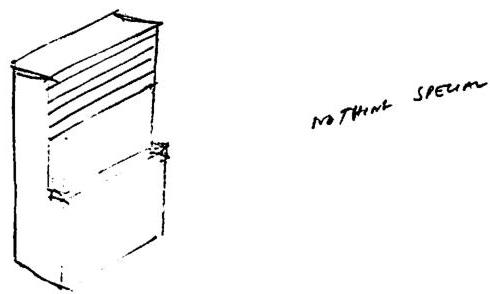

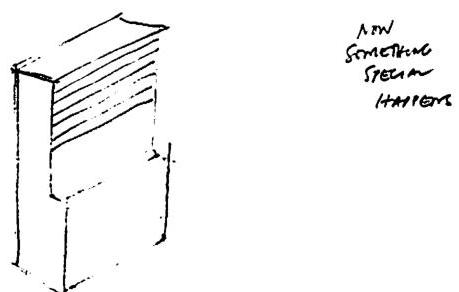

- STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

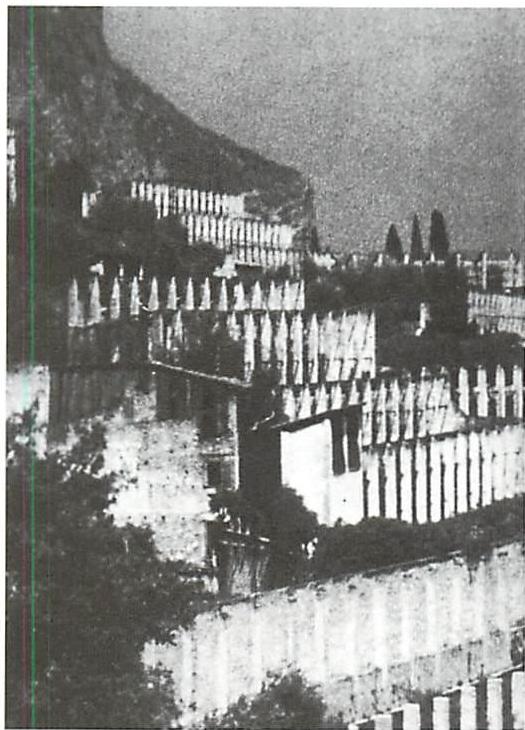

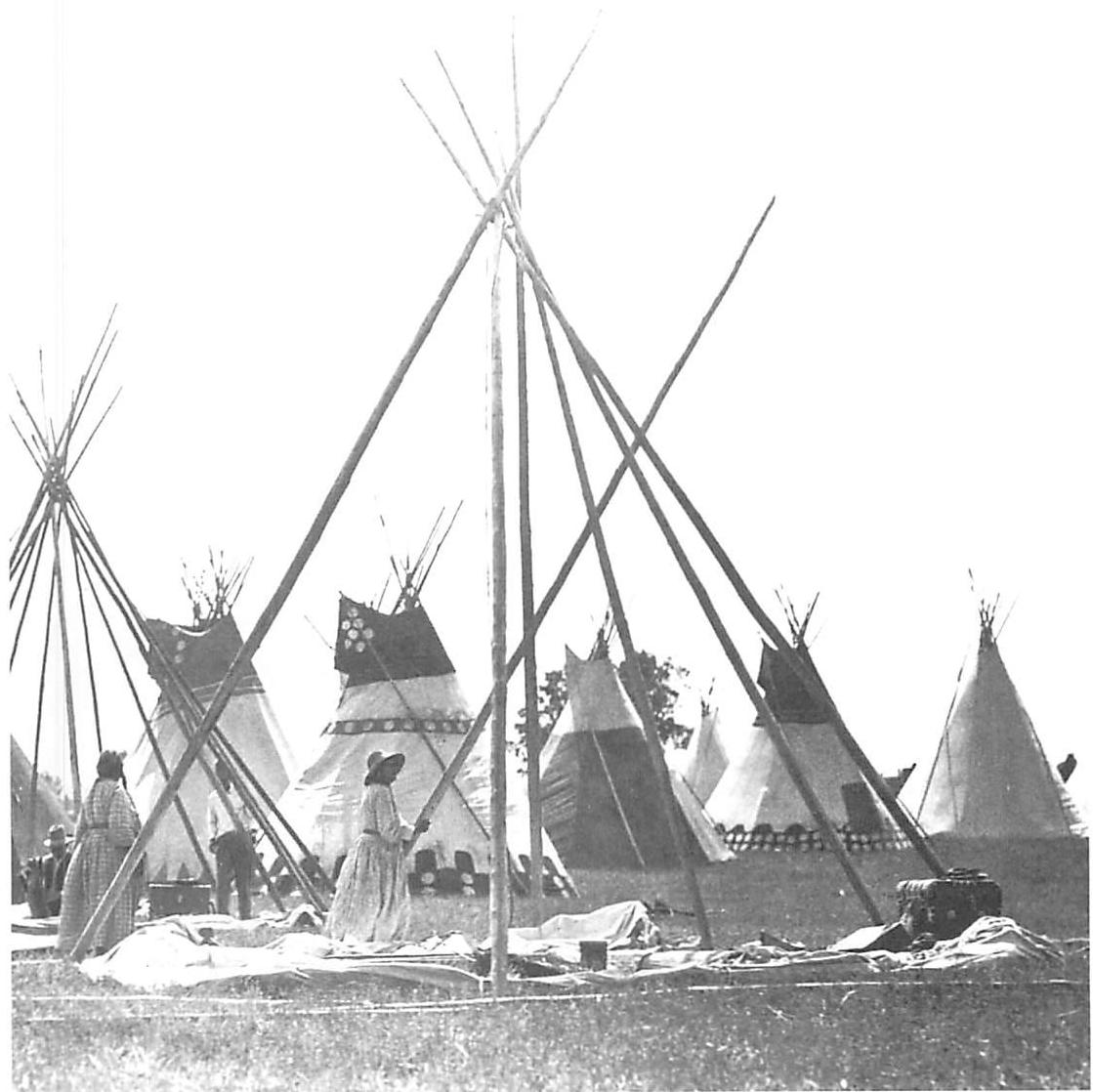

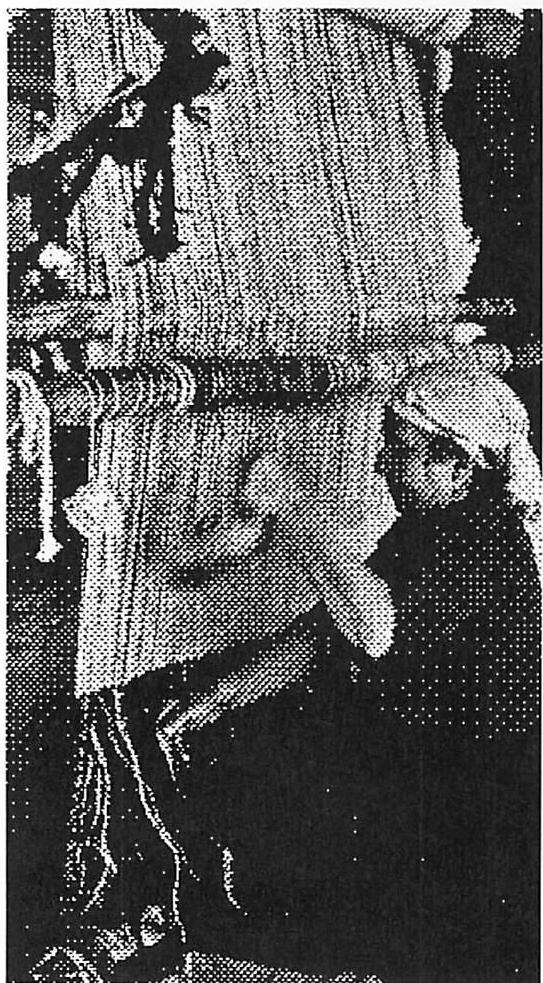

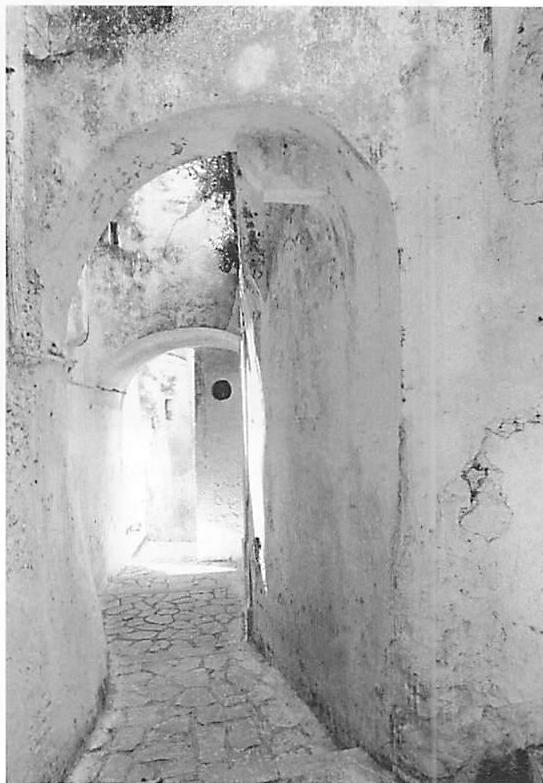

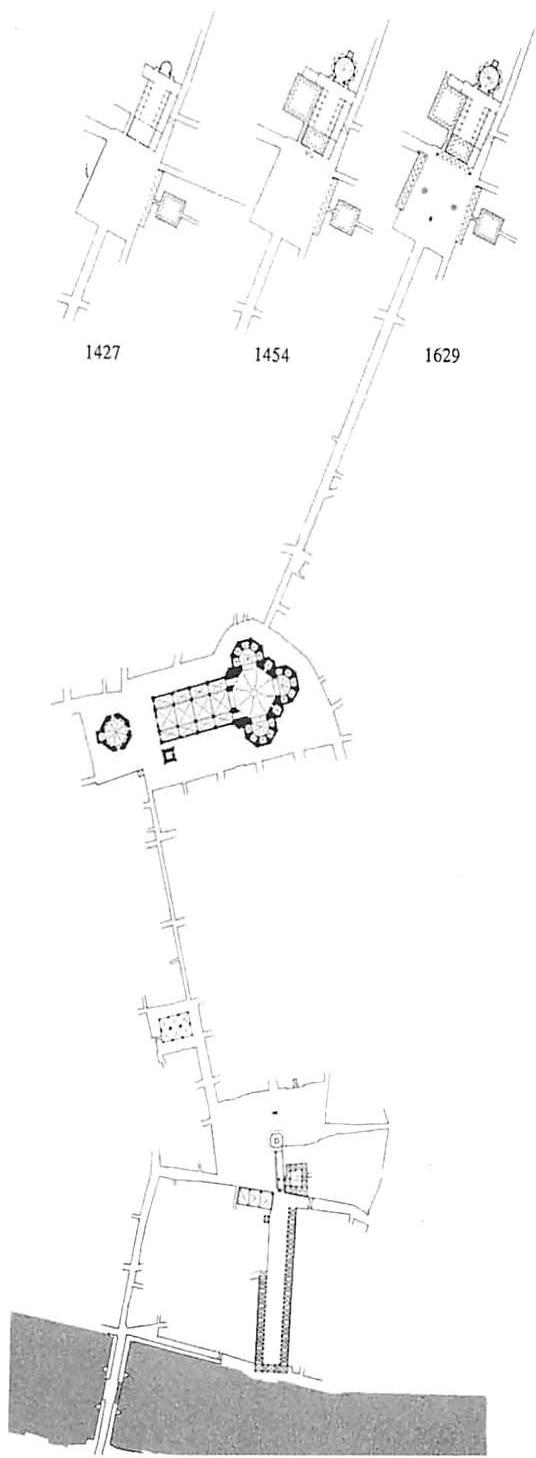

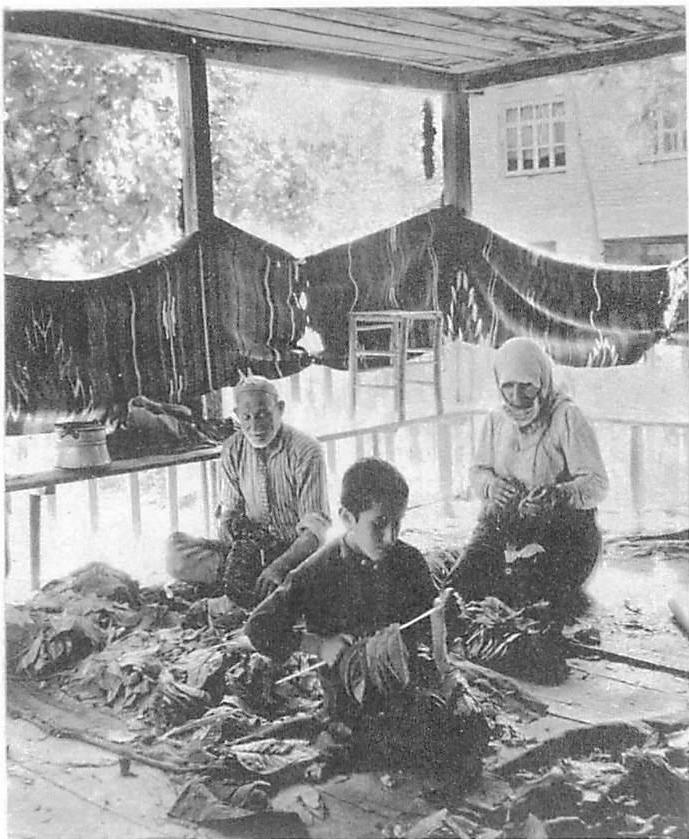

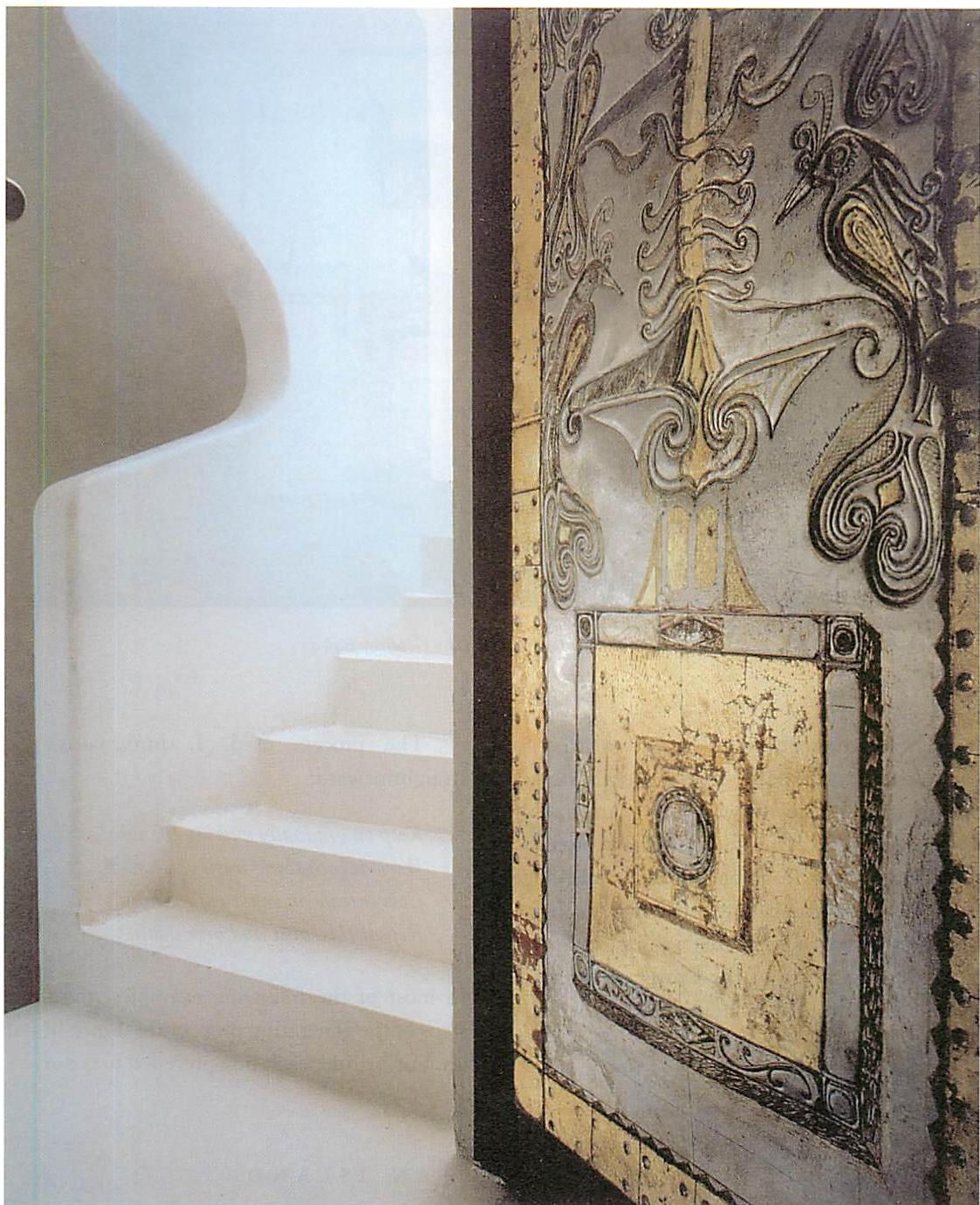

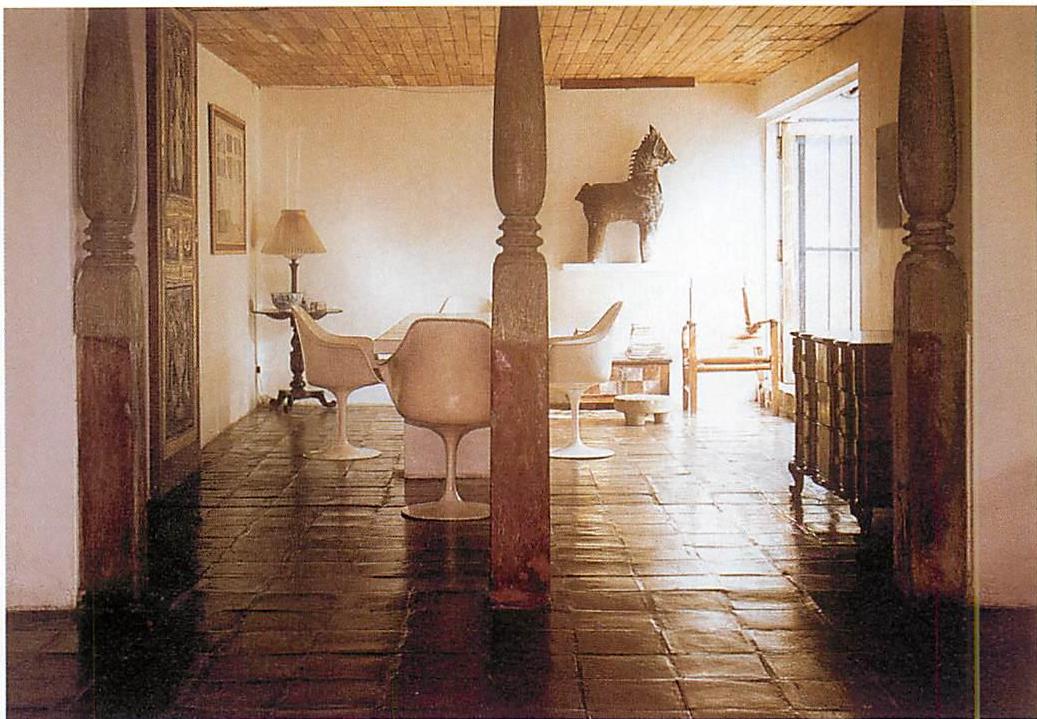

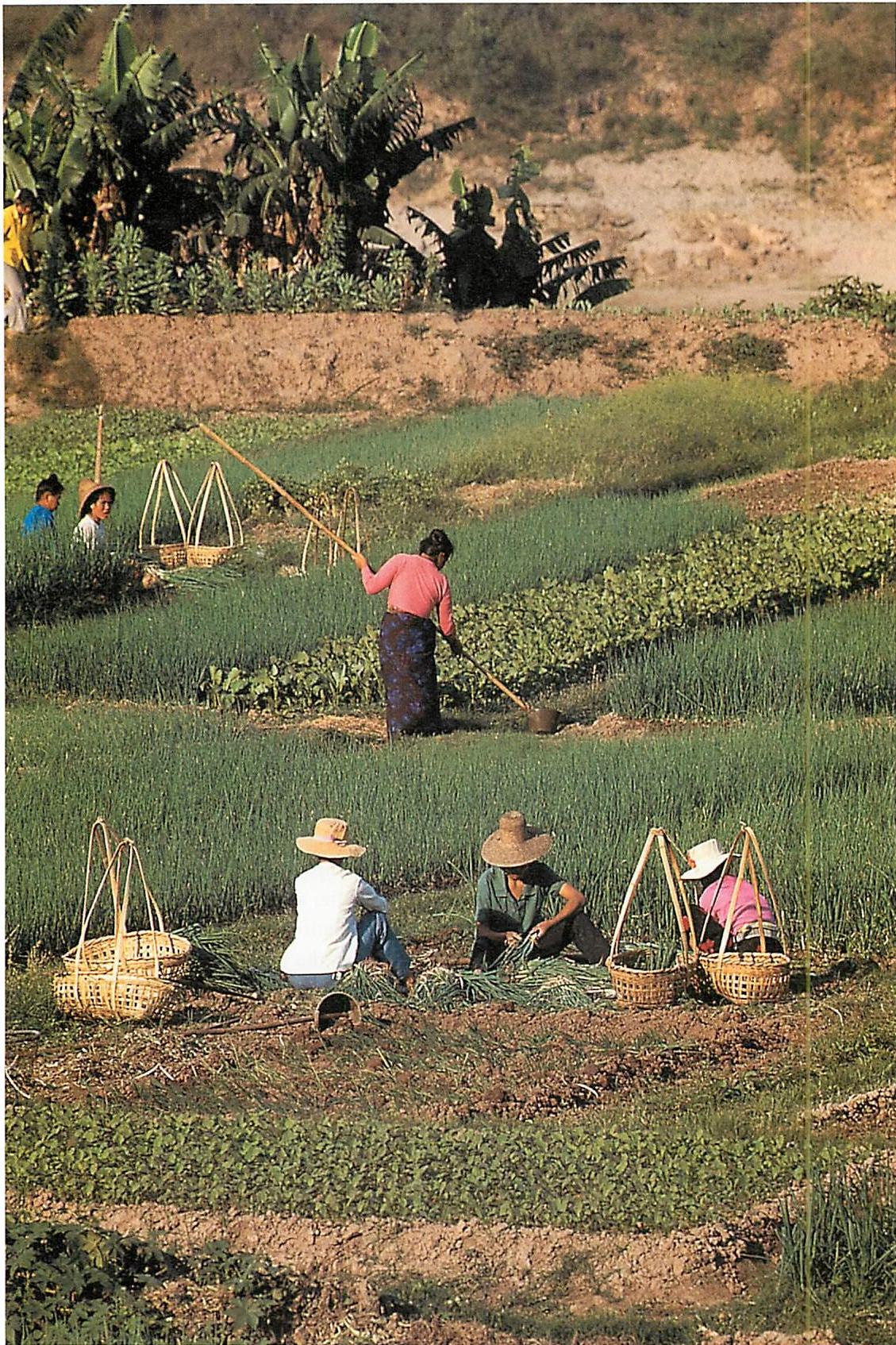

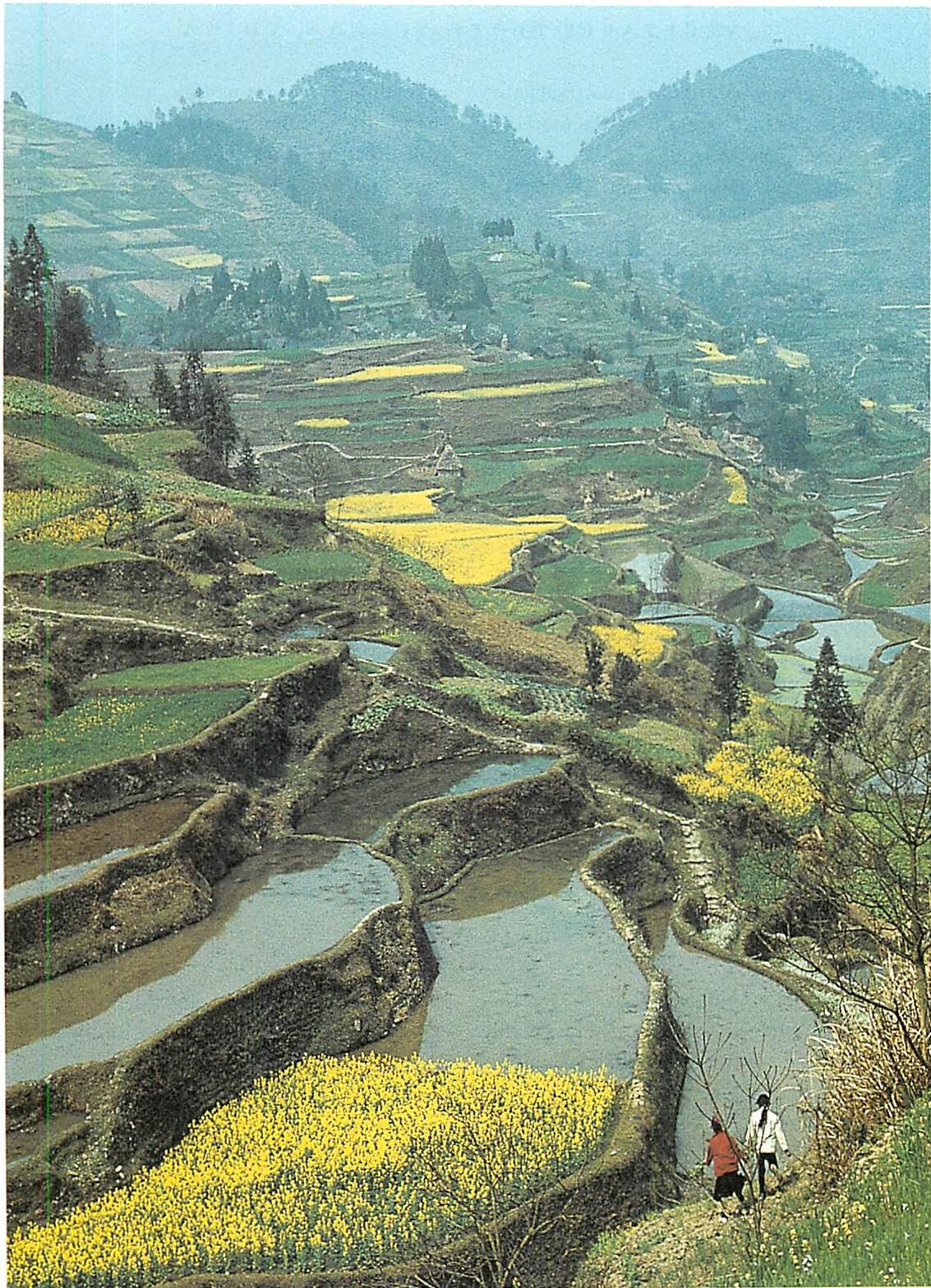

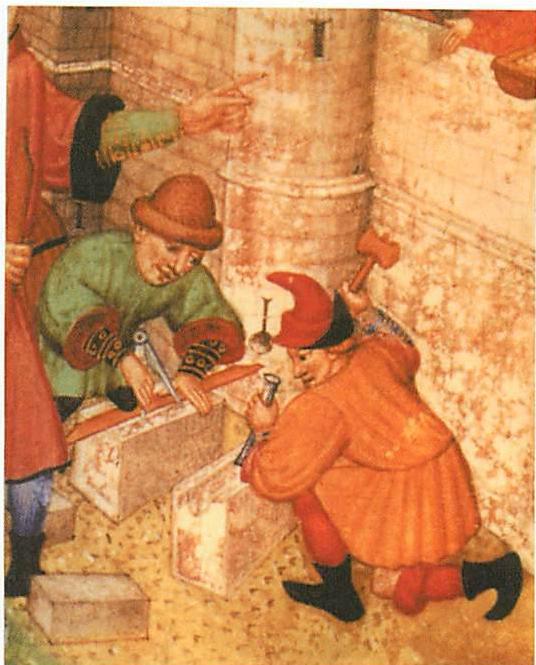

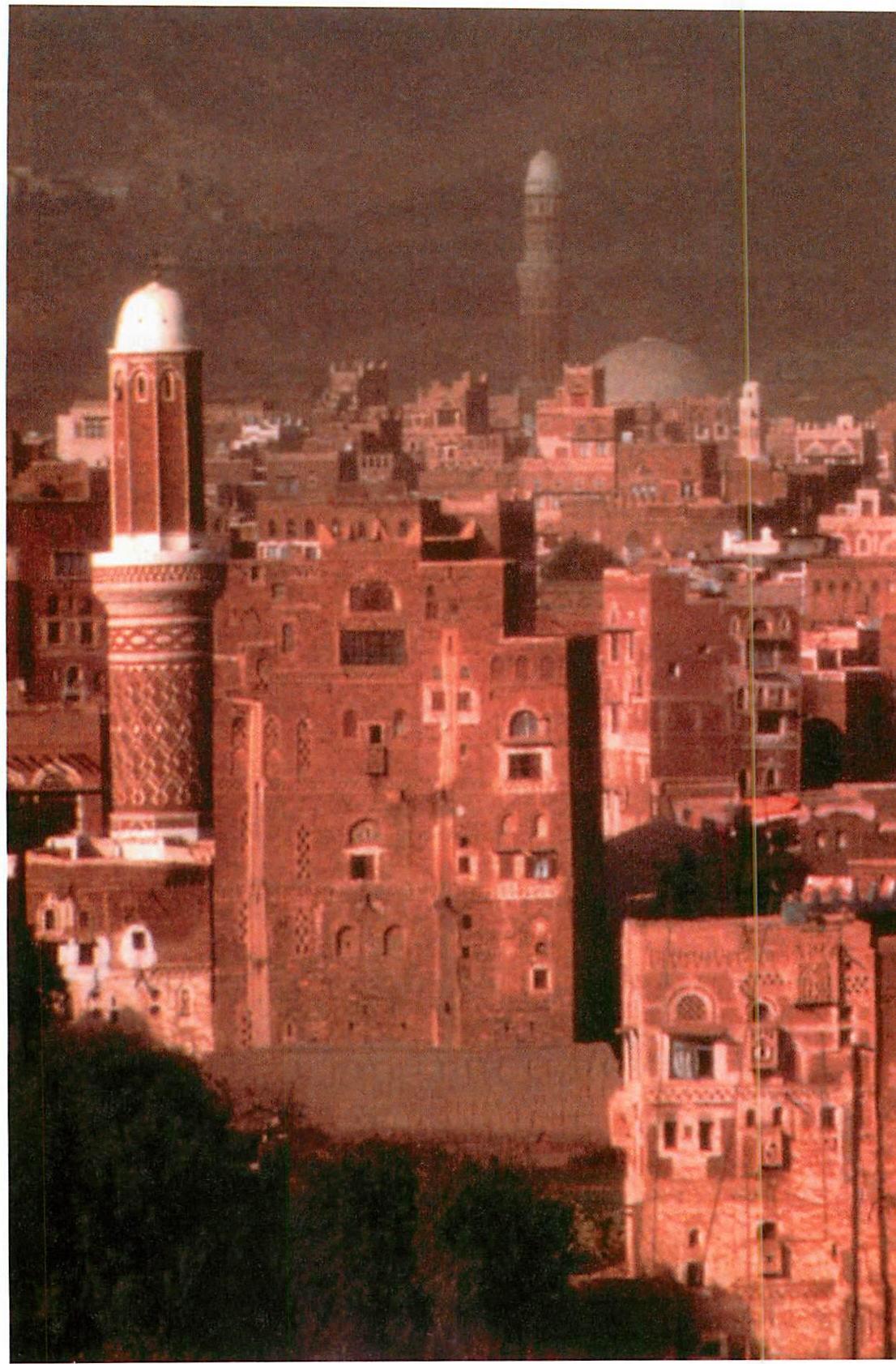

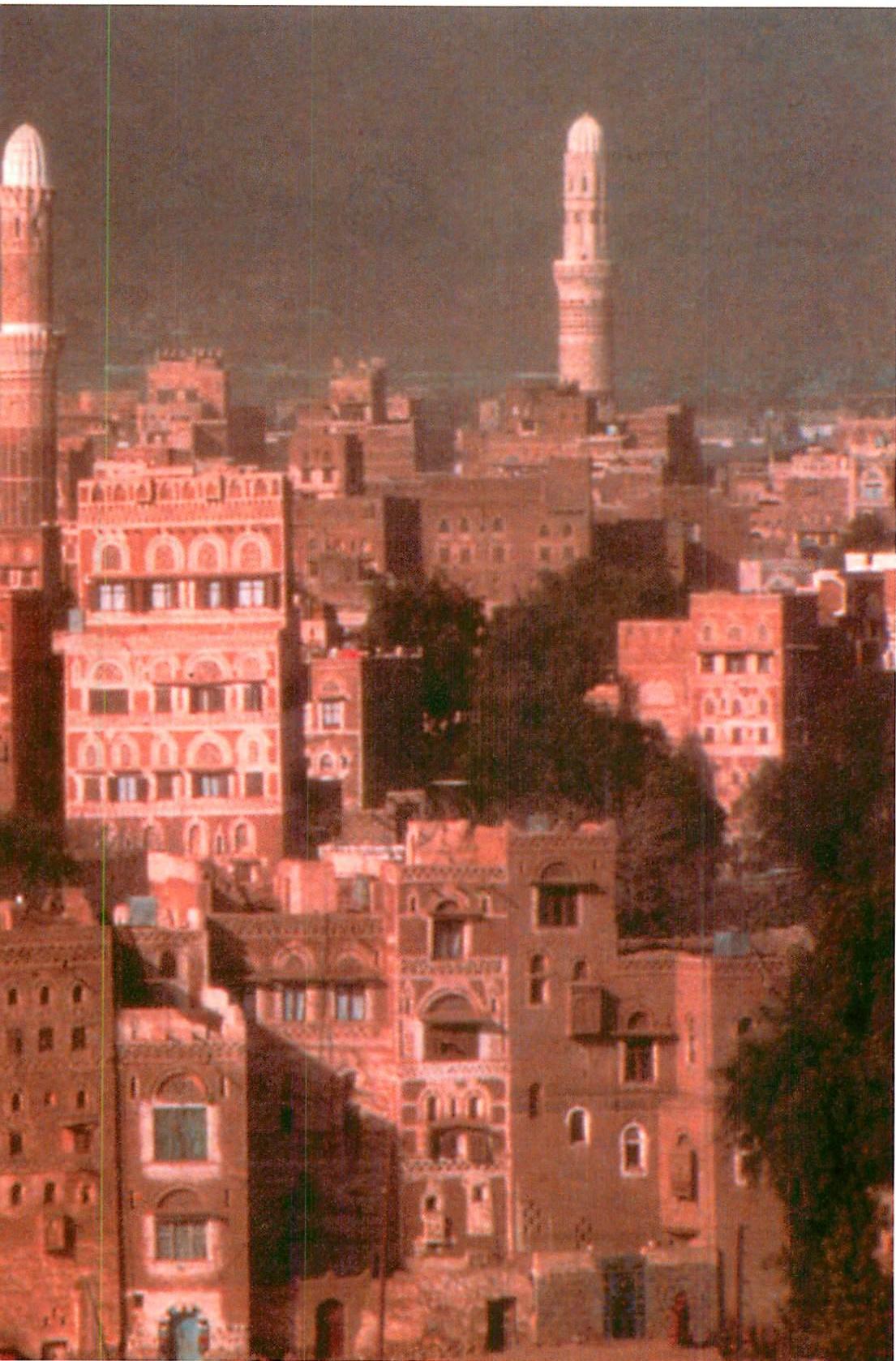

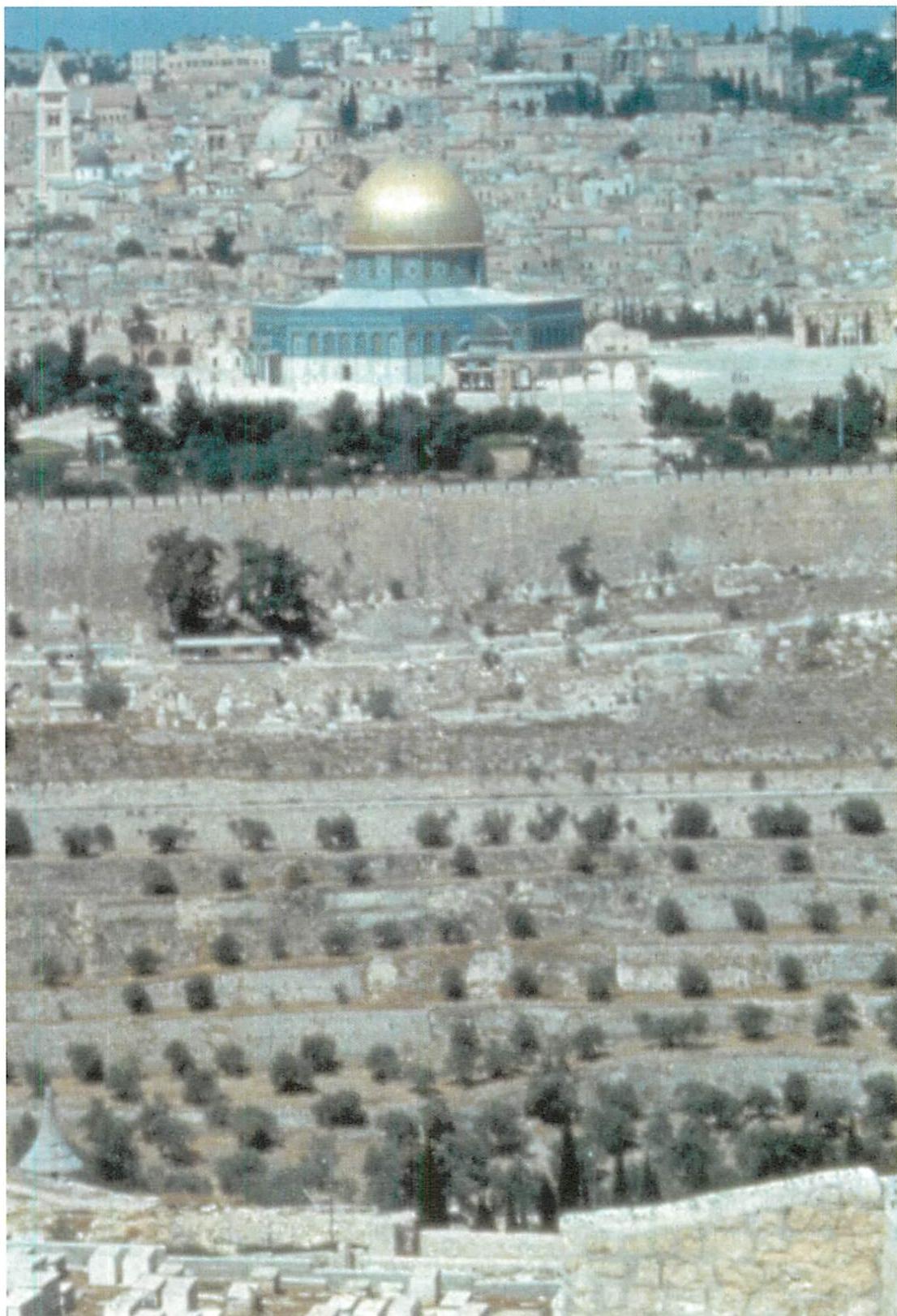

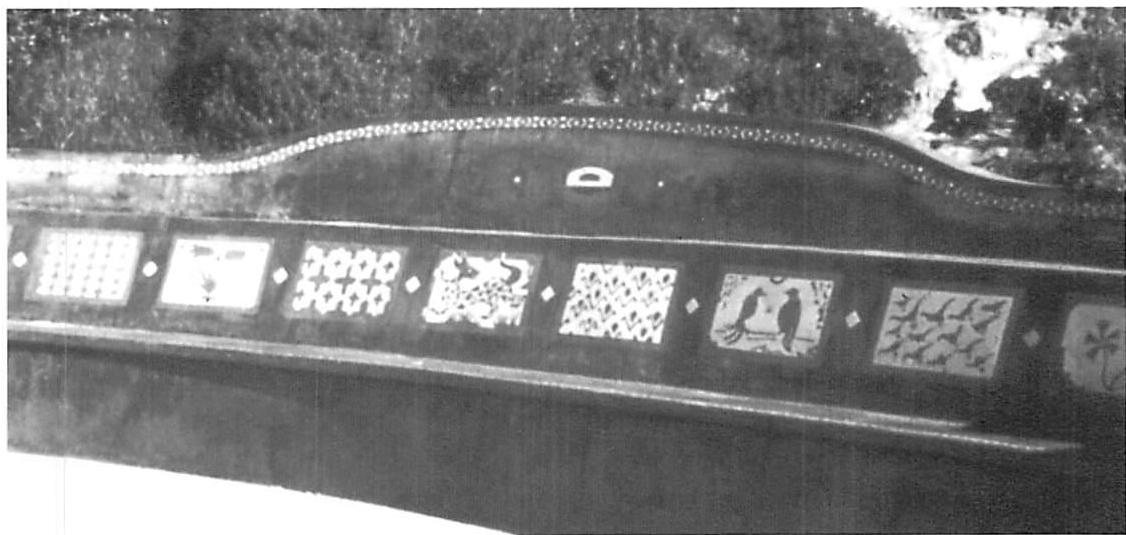

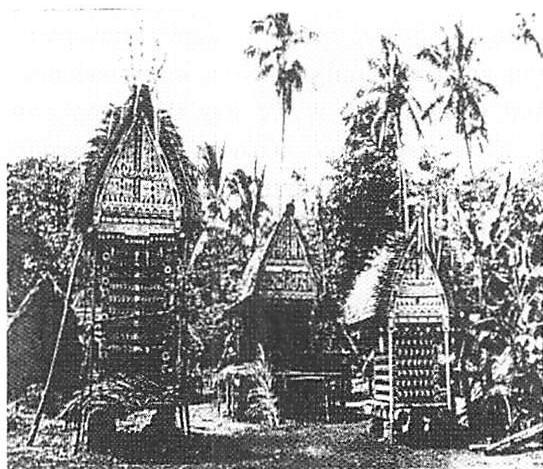

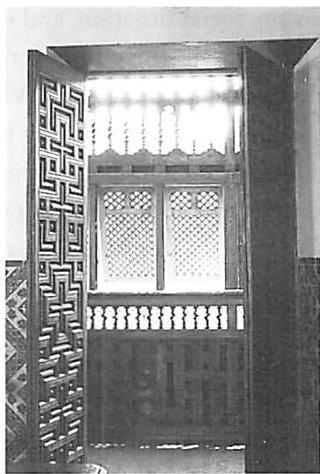

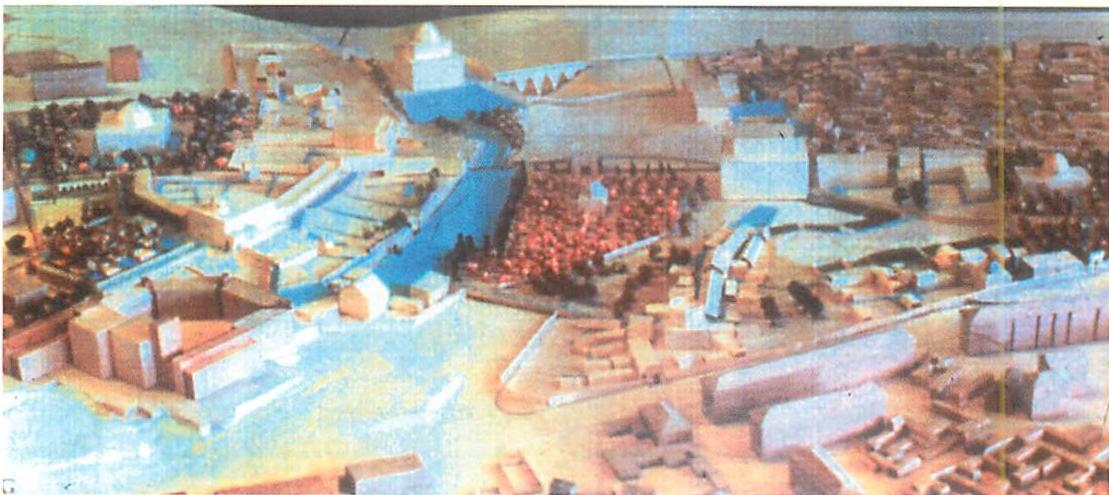

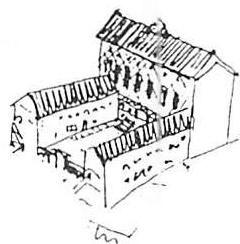

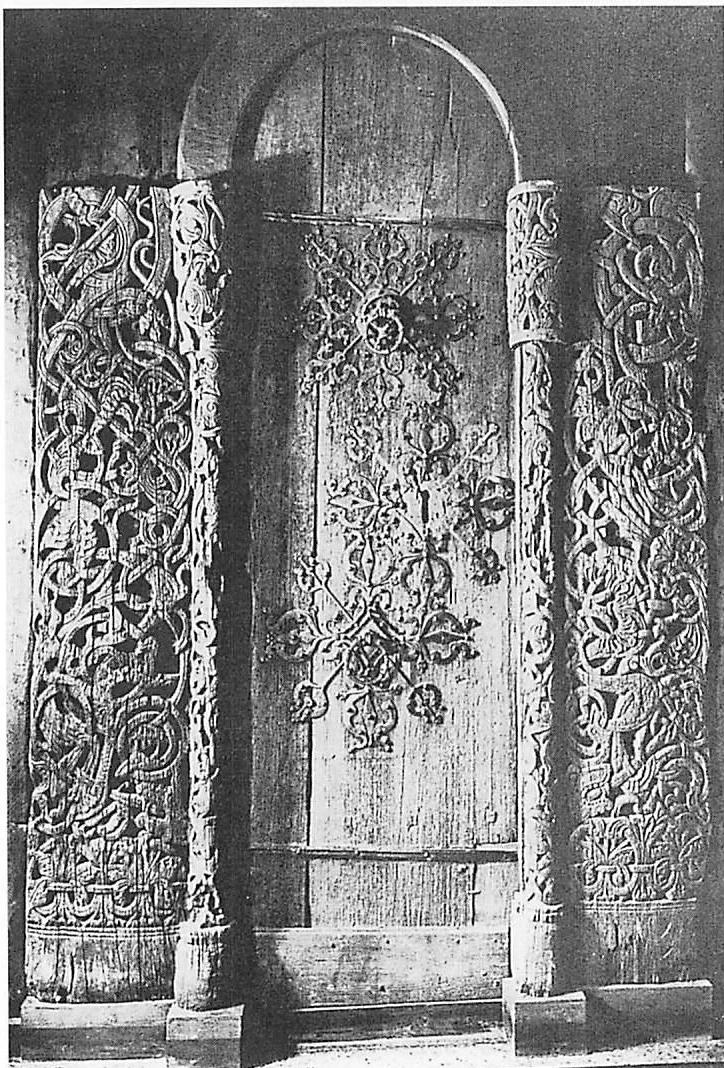

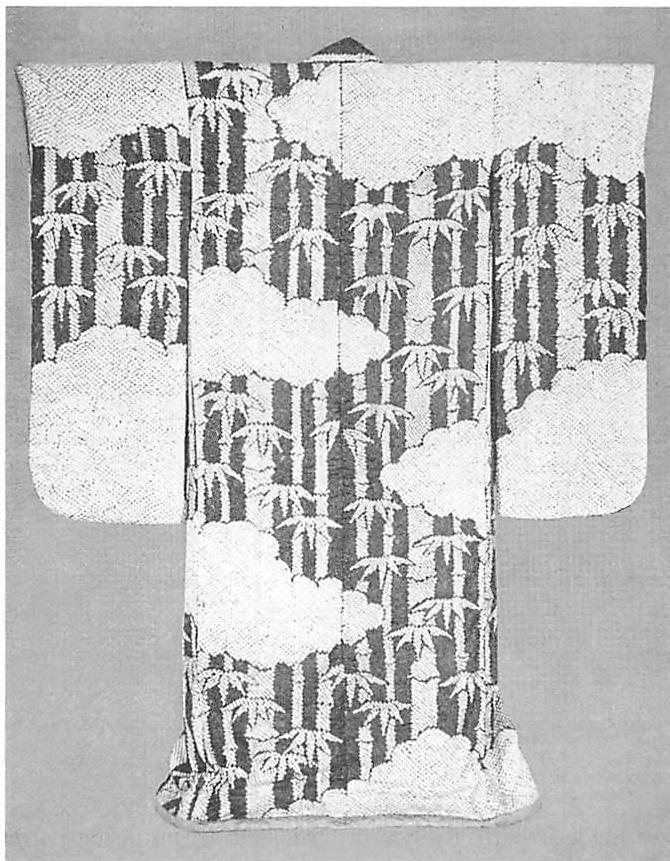

- STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRADITIONAL SOCIETY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

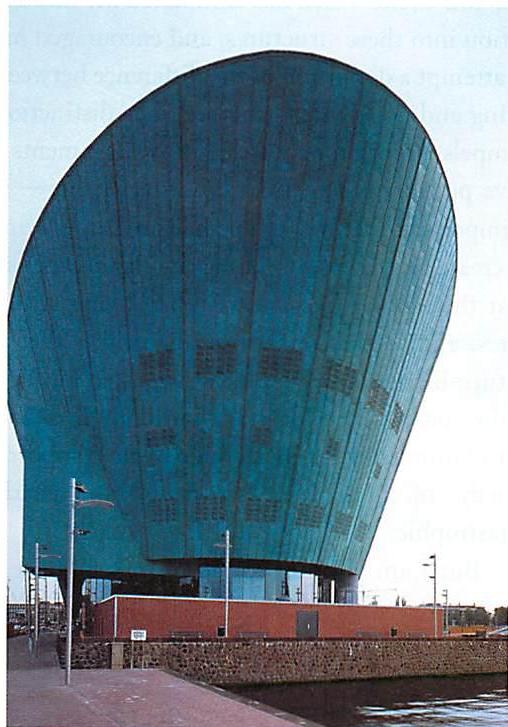

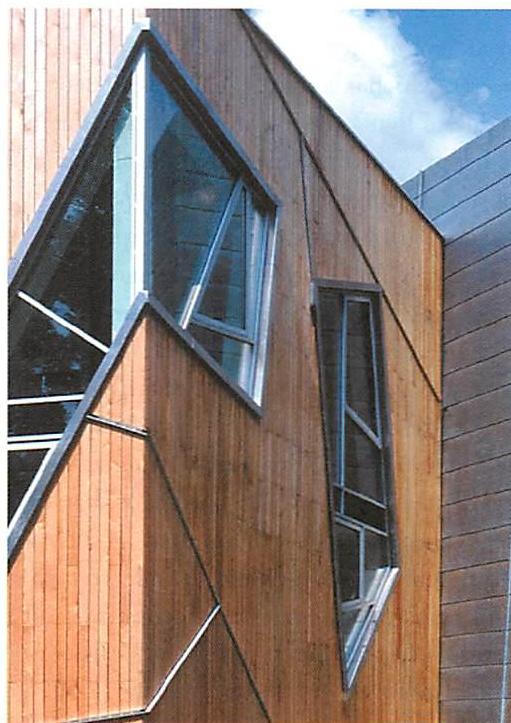

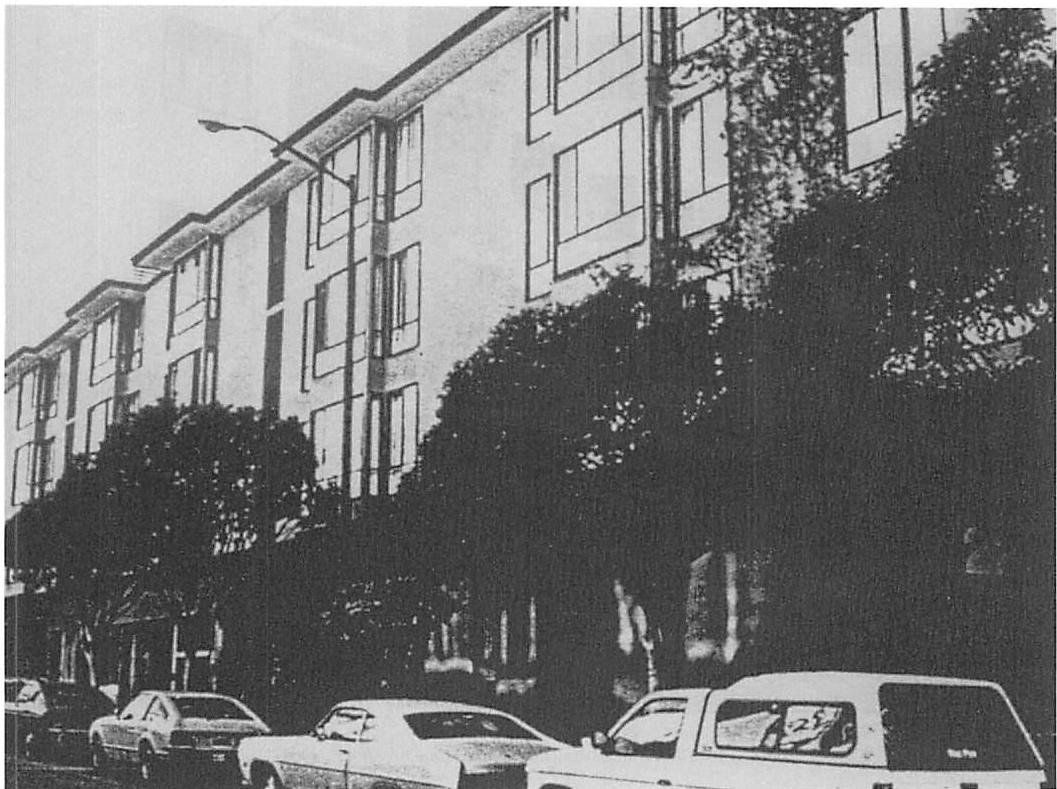

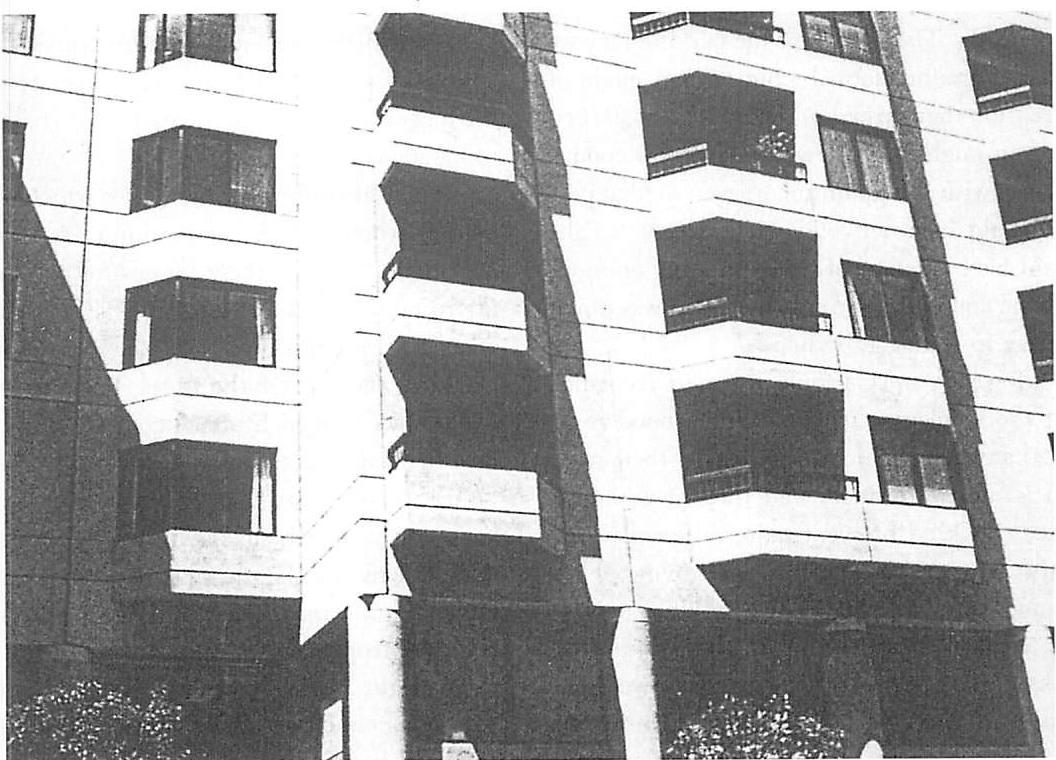

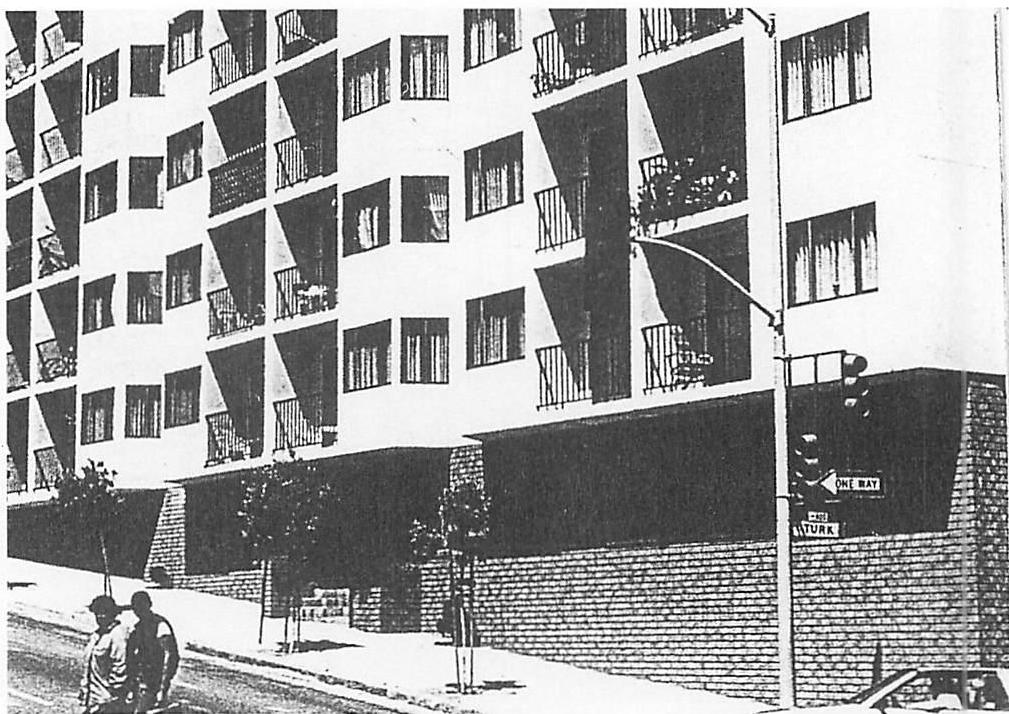

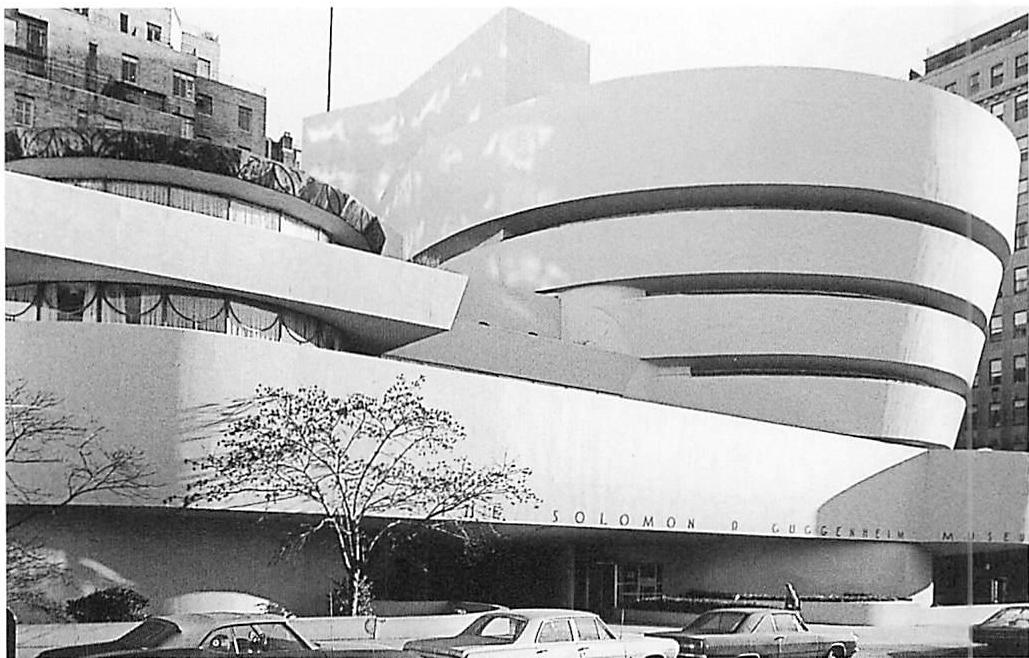

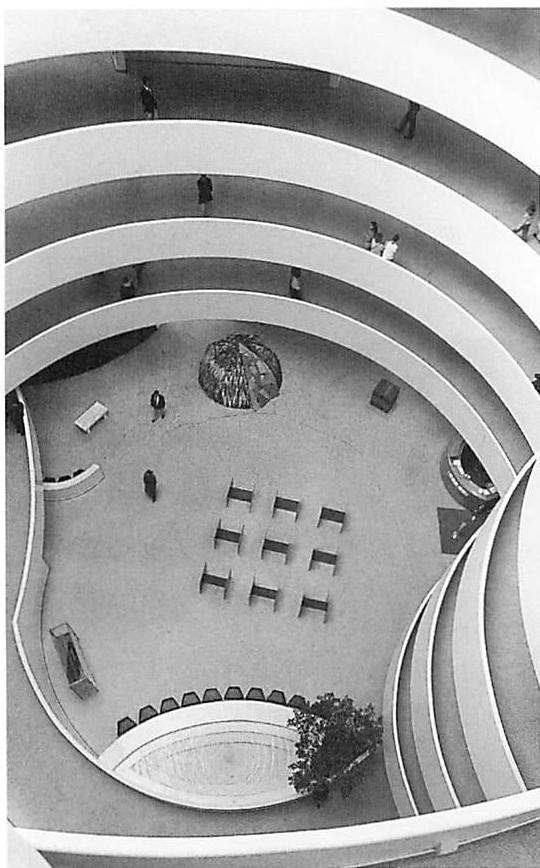

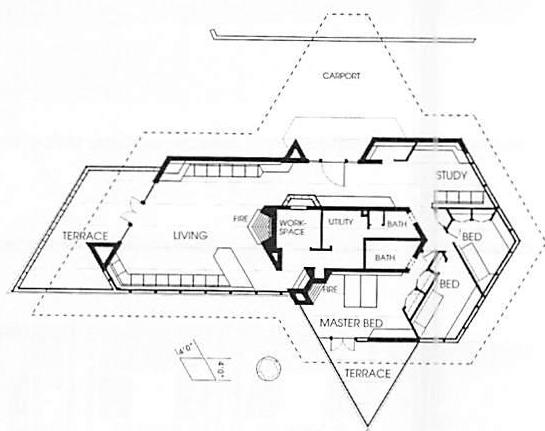

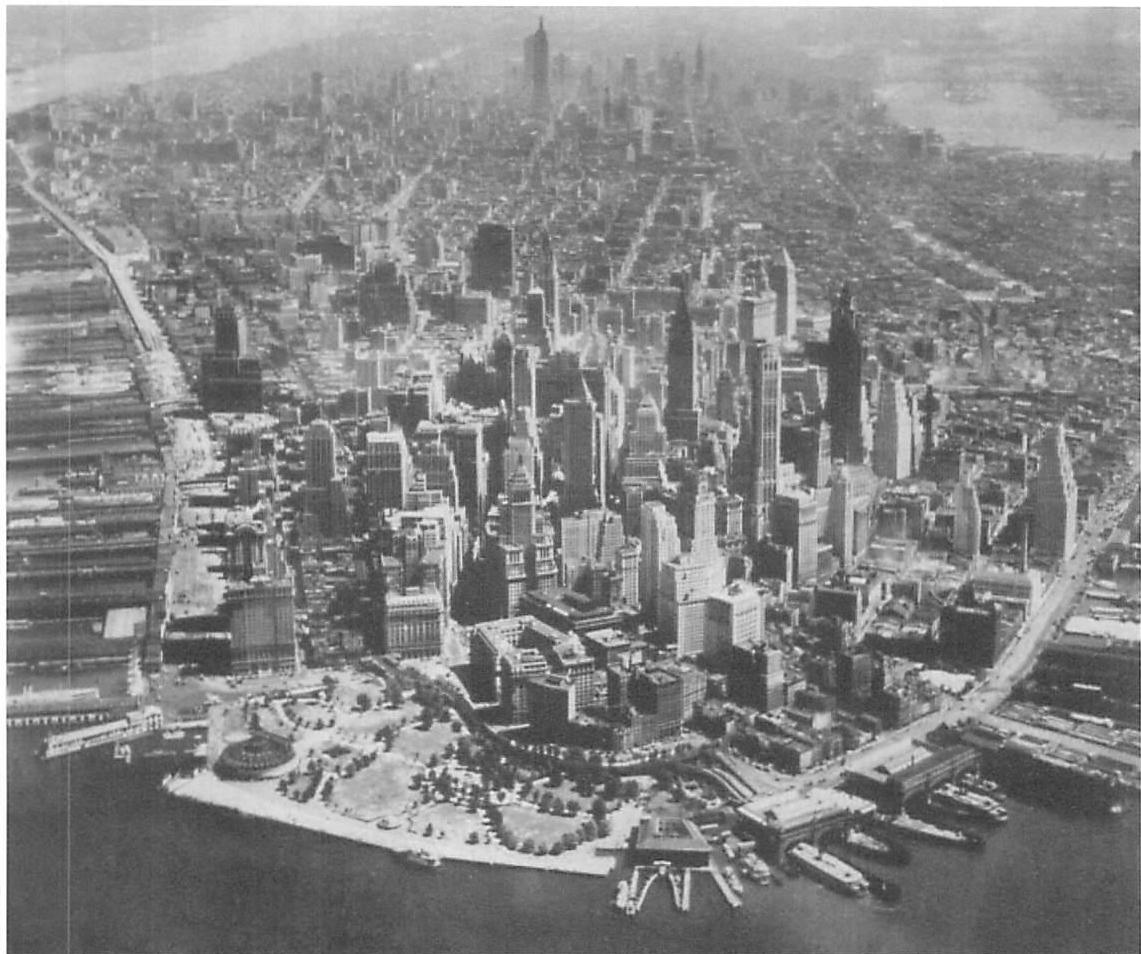

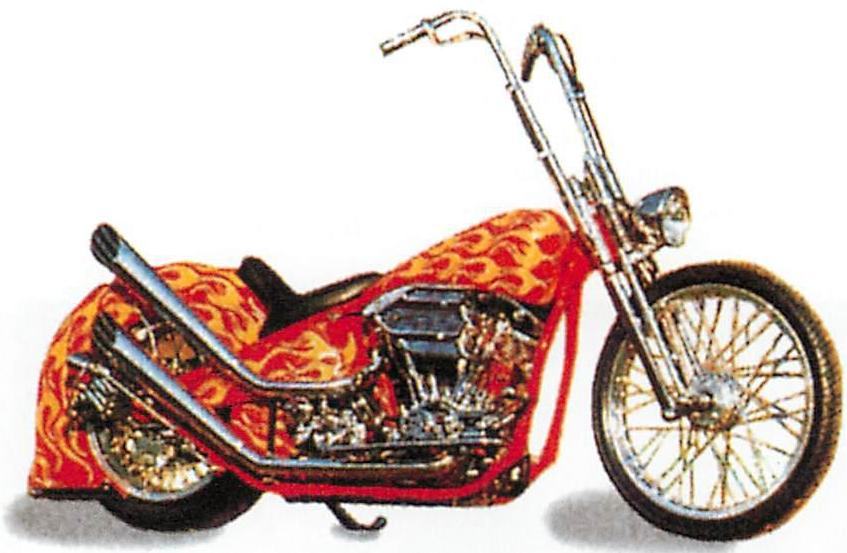

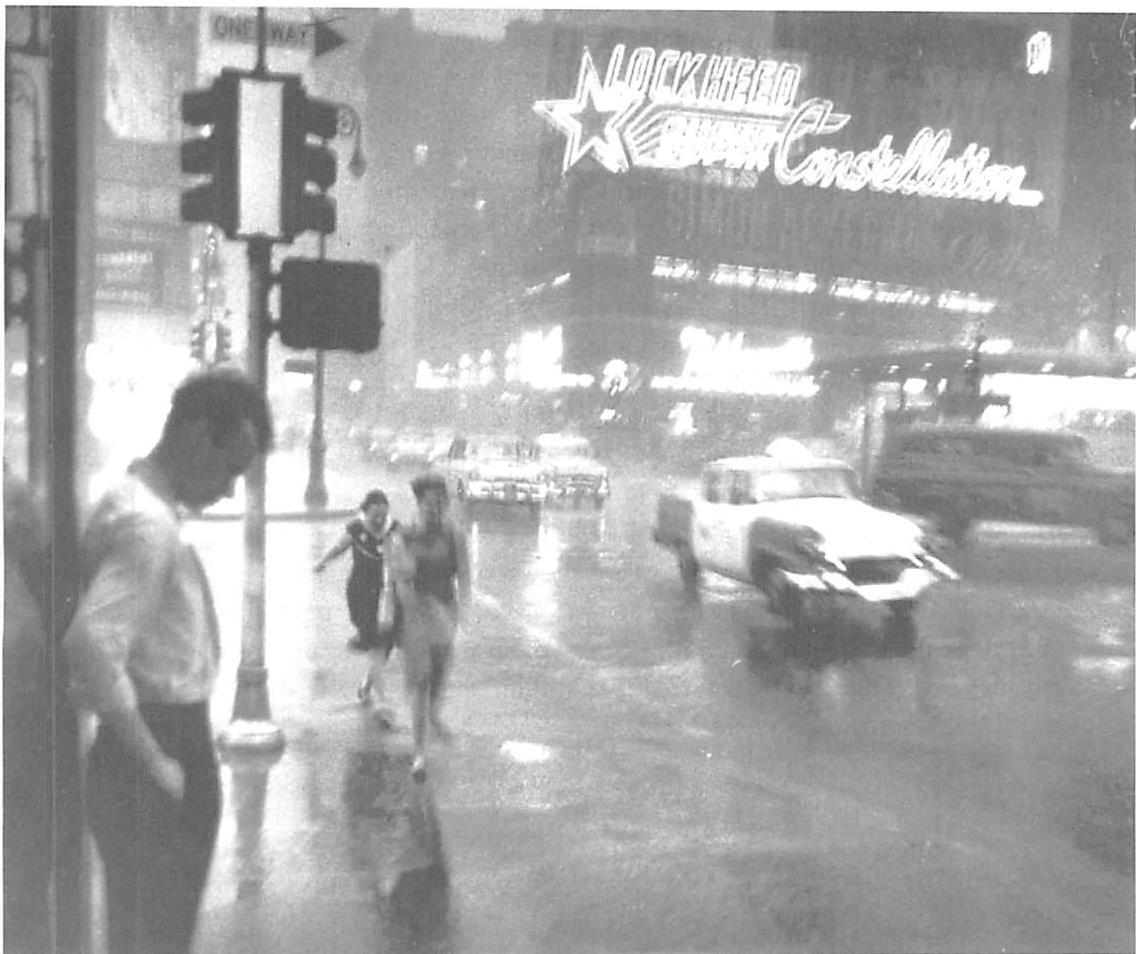

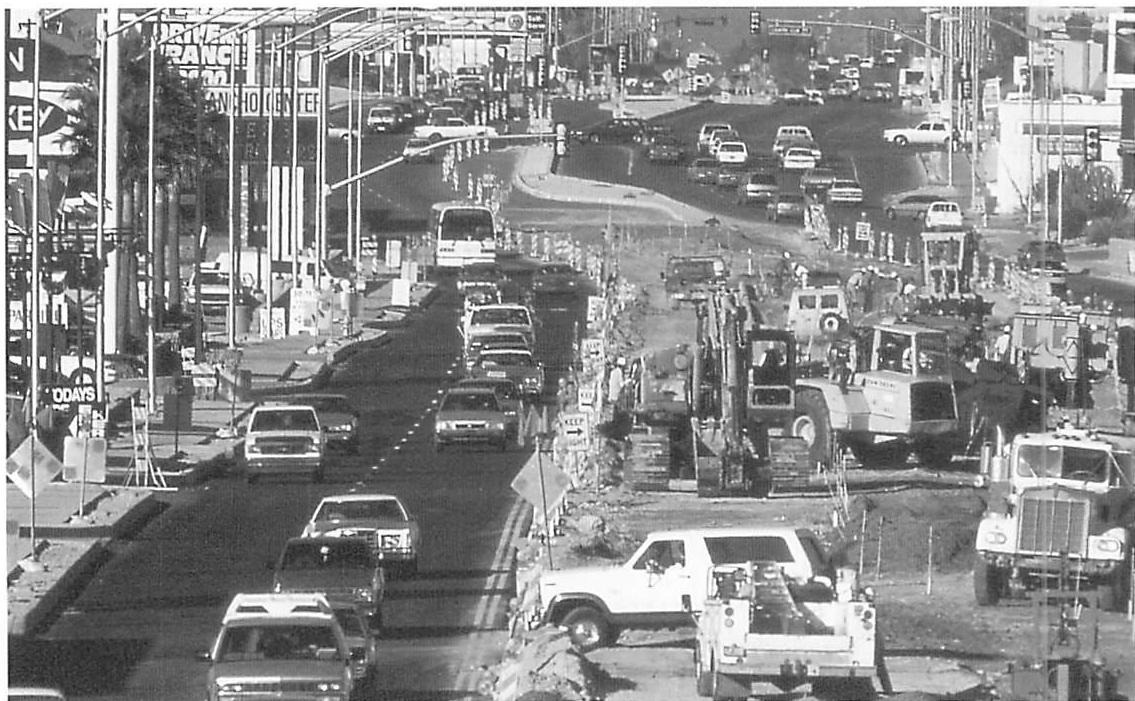

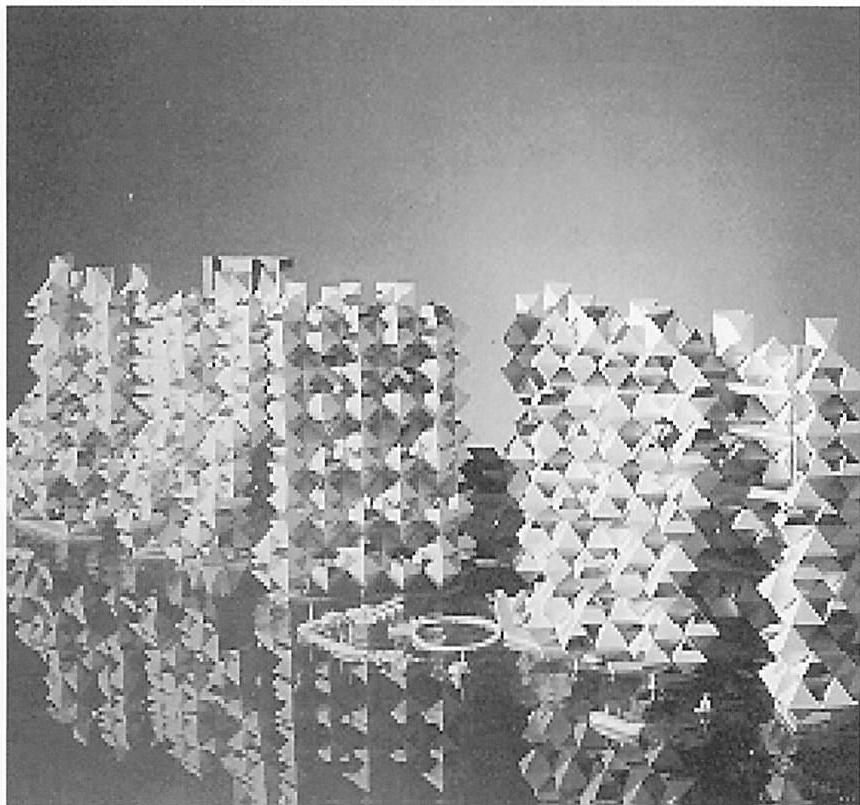

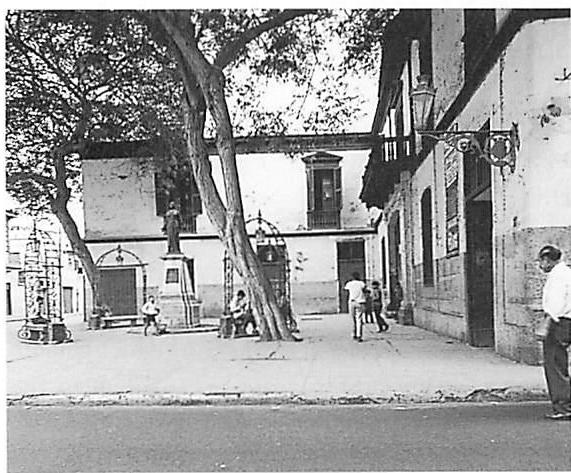

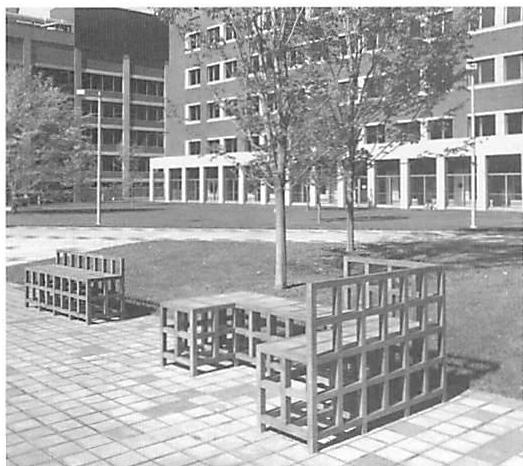

- STRUCTURE-DESTROYING TRANSFORMATIONS IN MODERN SOCIETY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

INTERLUDE

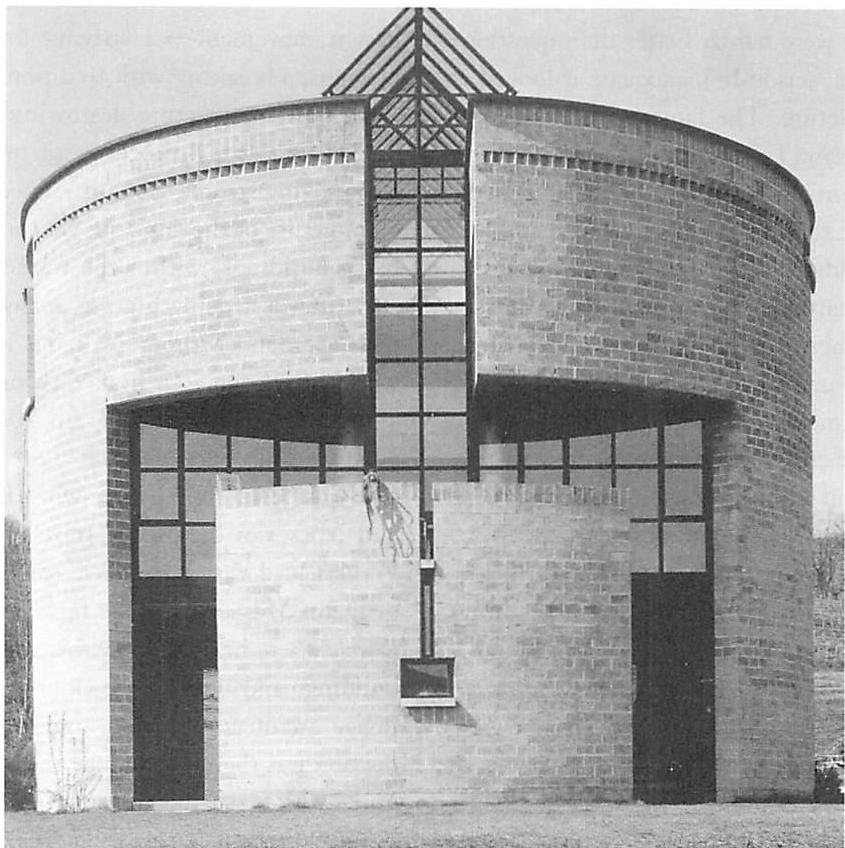

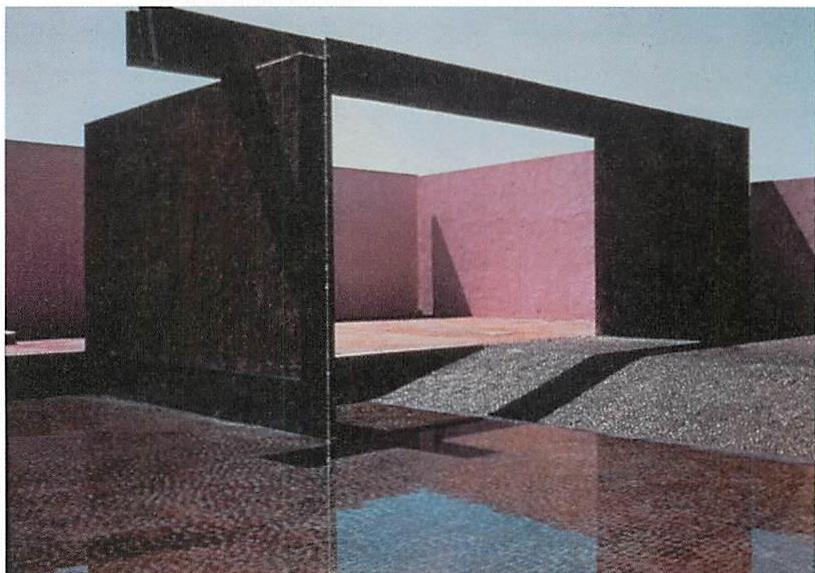

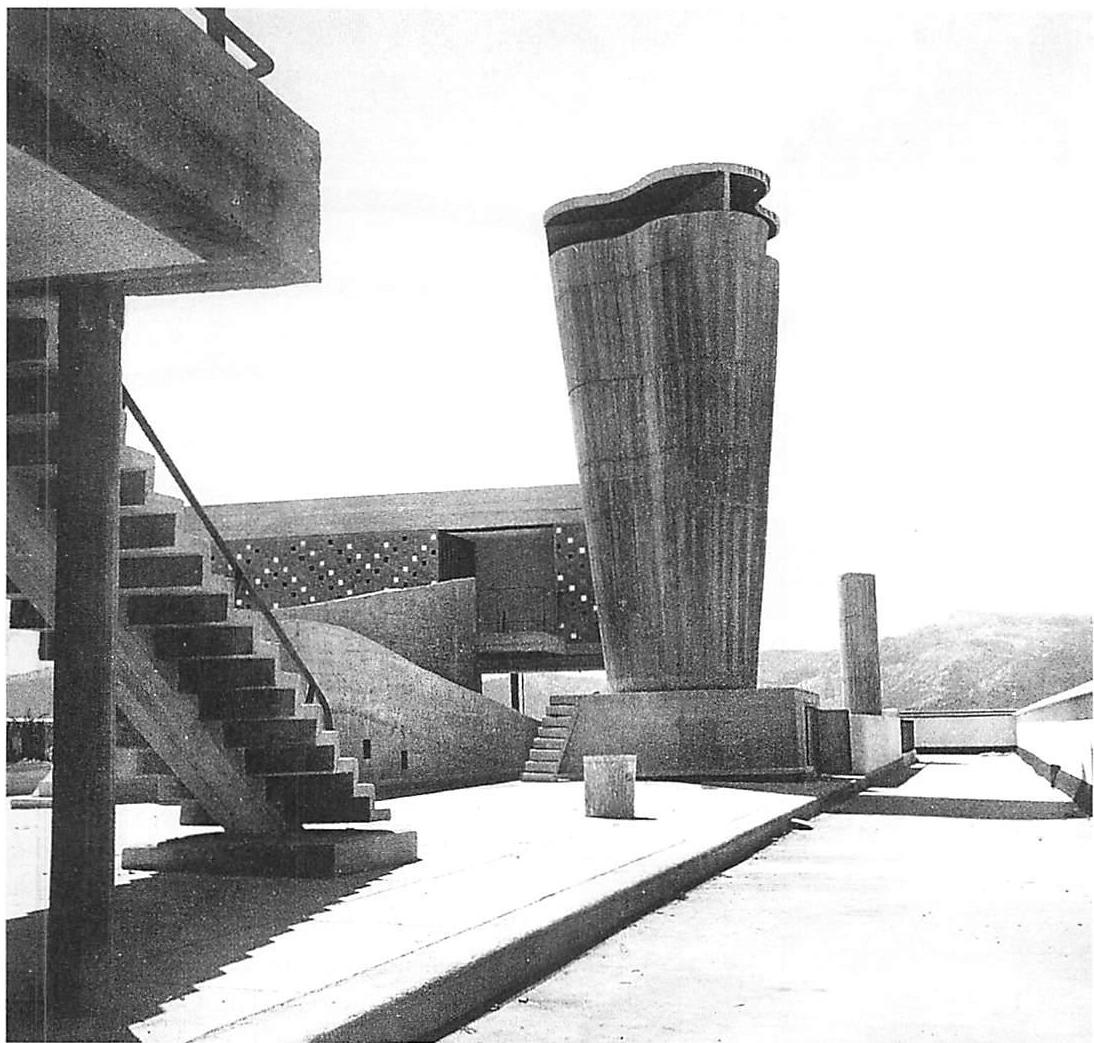

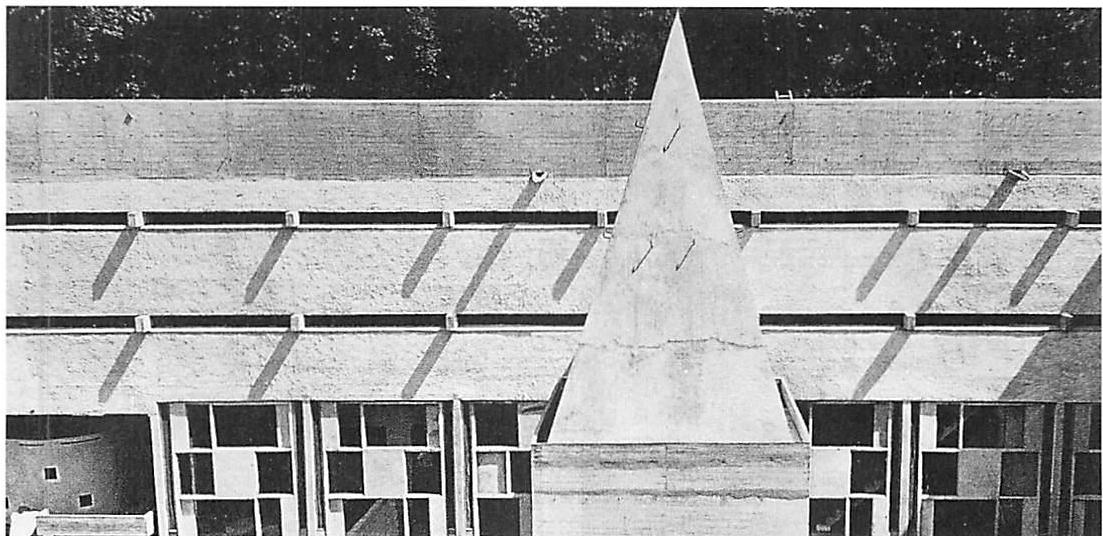

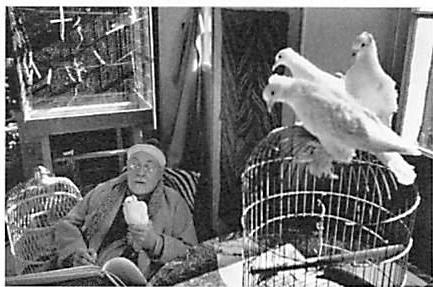

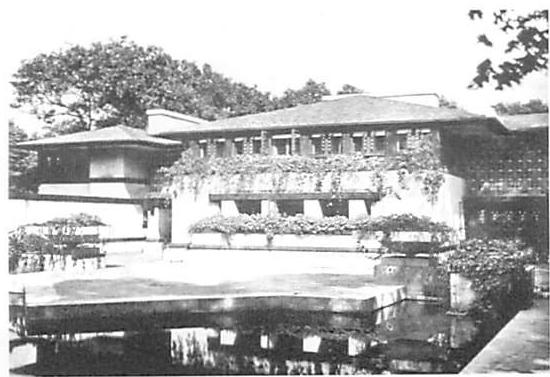

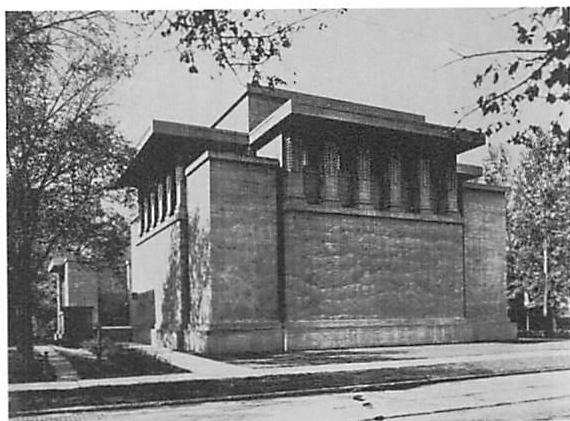

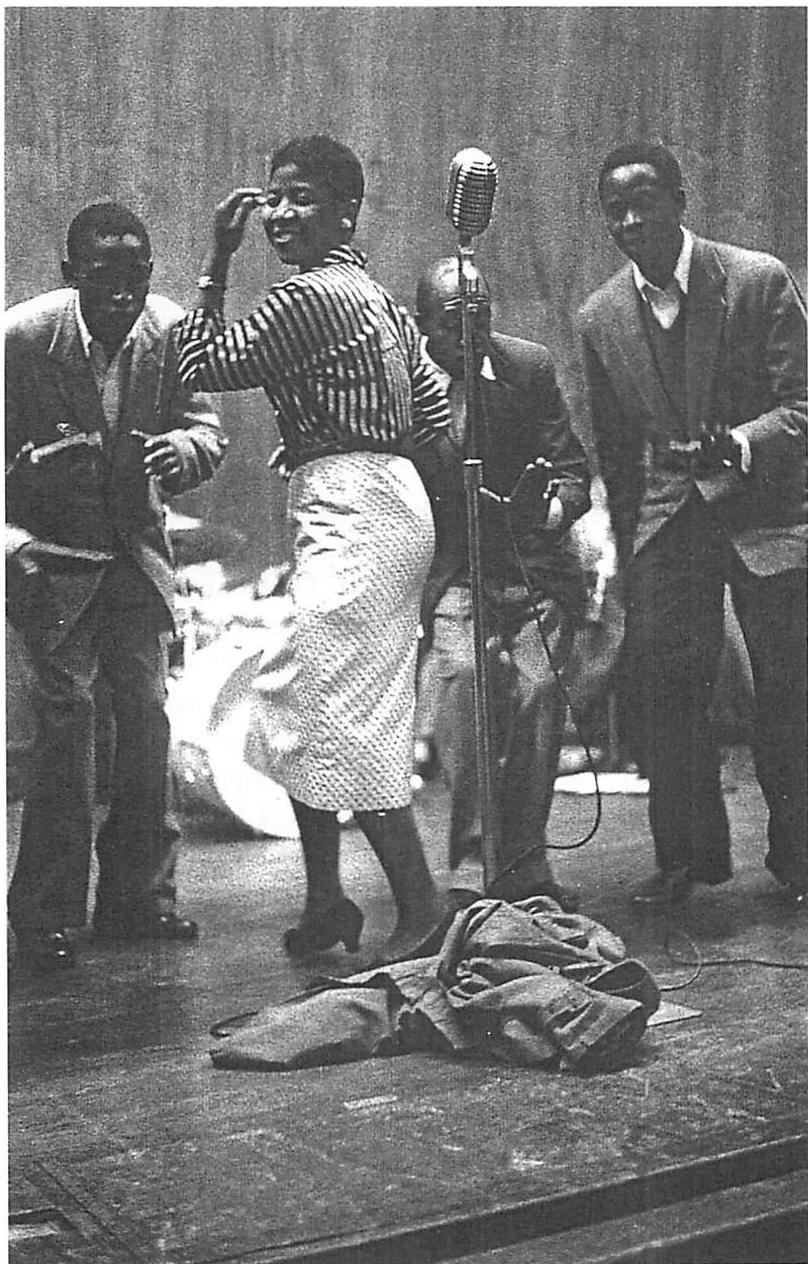

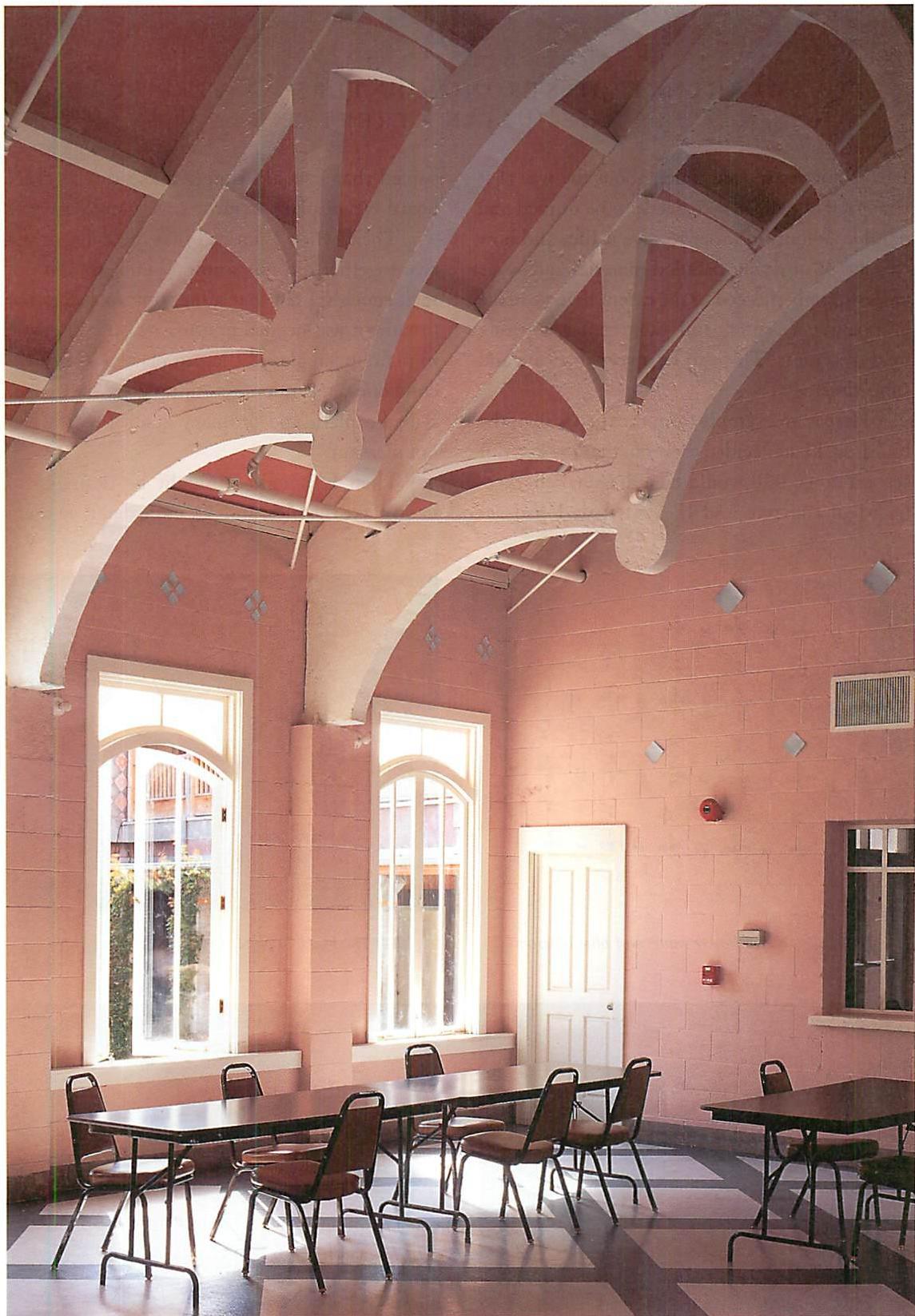

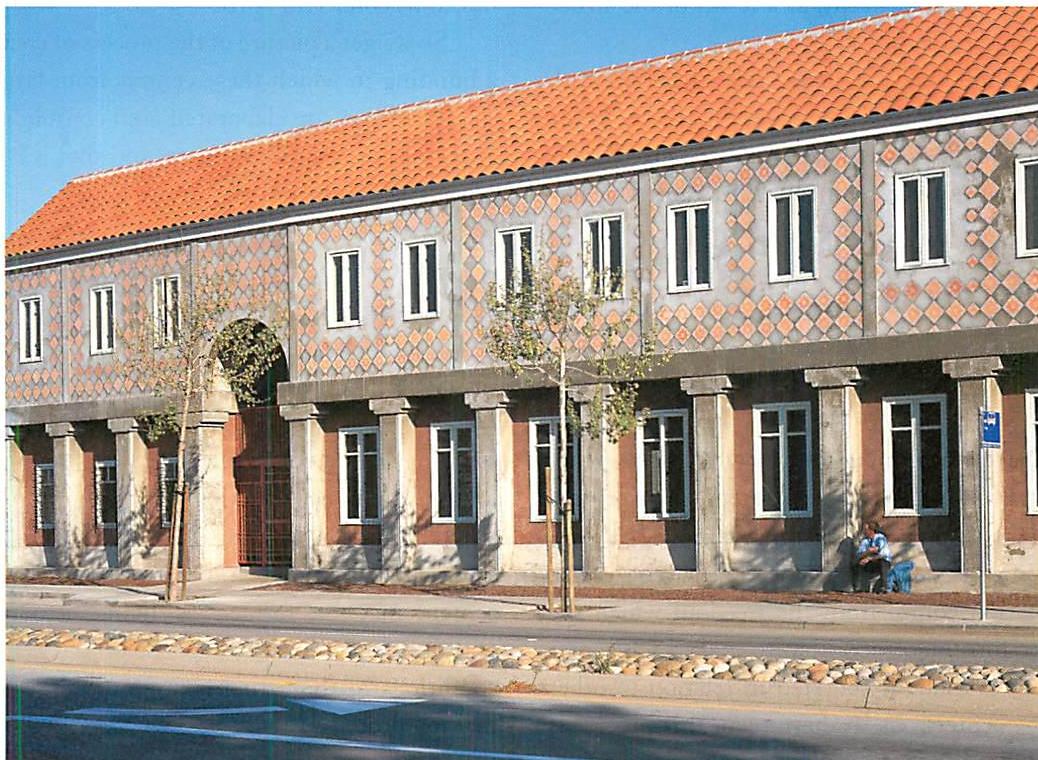

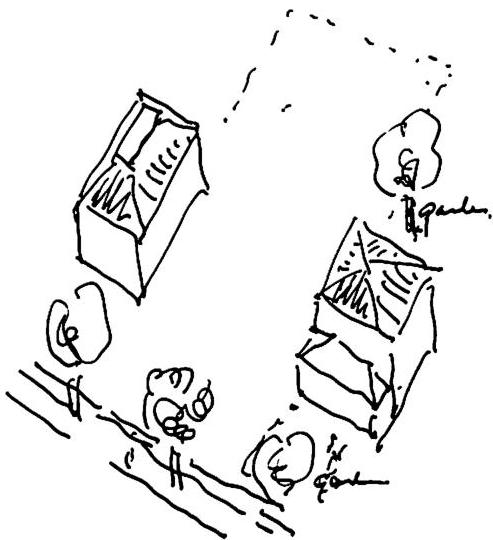

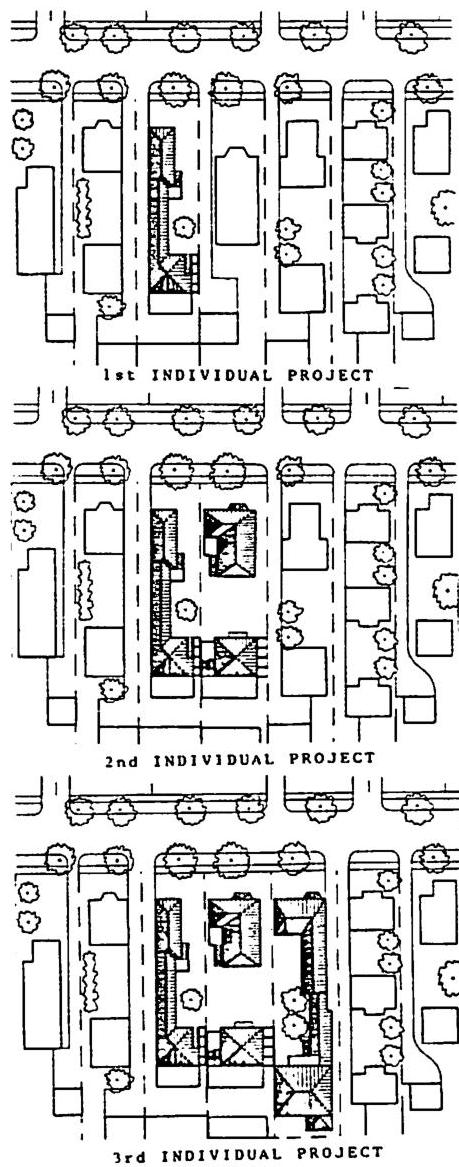

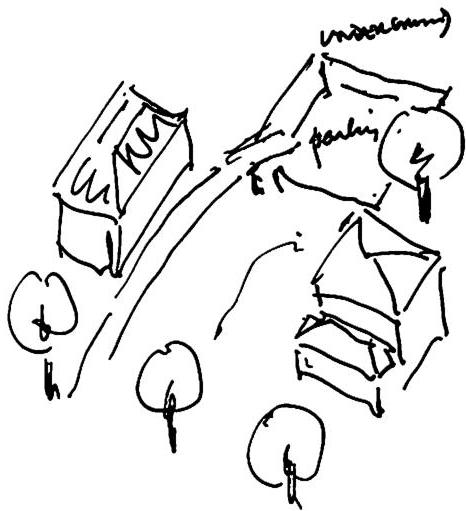

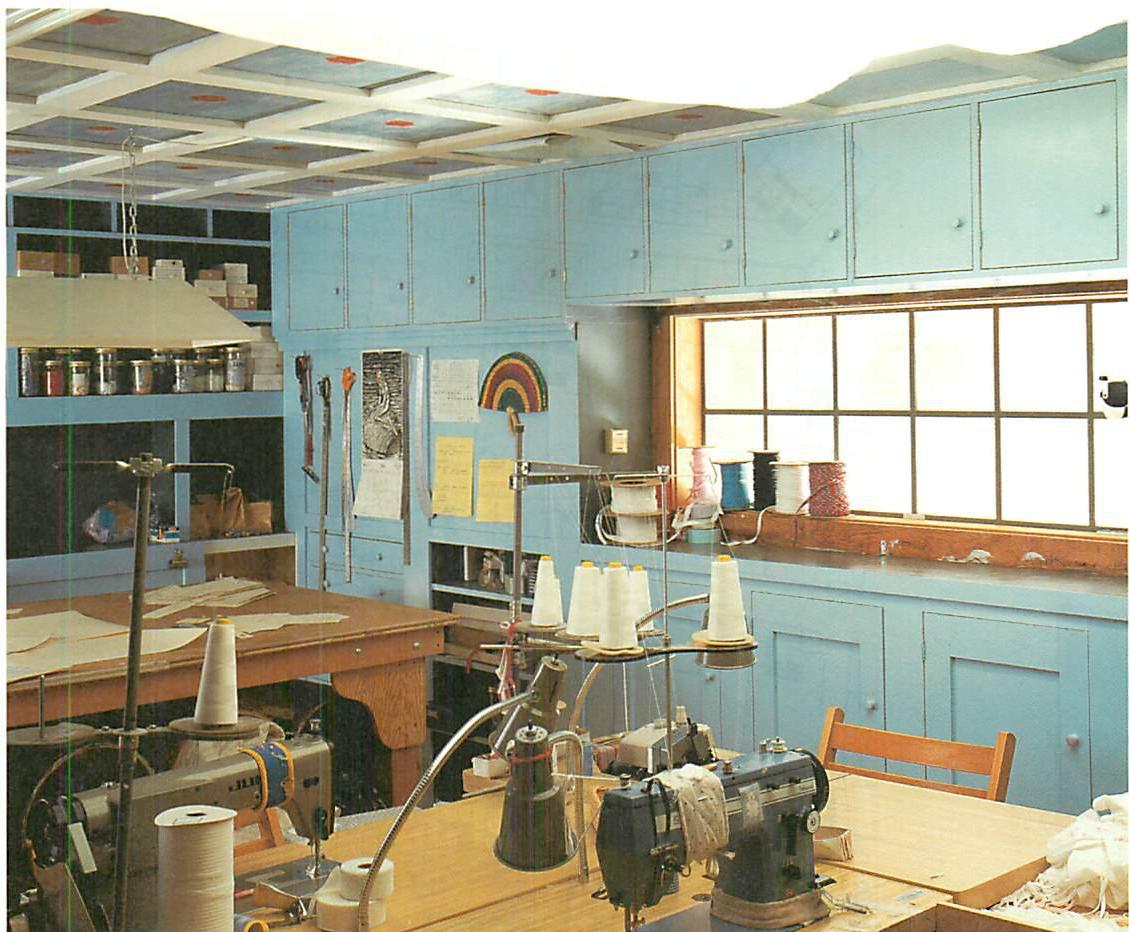

- LIVING PROCESS IN THE MODERN ERA: TWENTIETH-CENTURY CASES WHERE LIVING PROCESS DID OCCUR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

PART TWO: LIVING PROCESSES

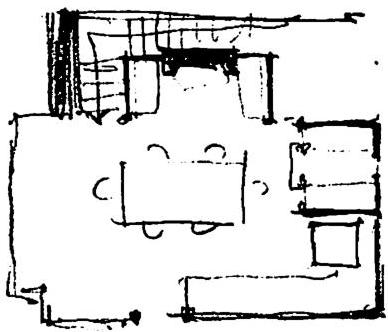

- GENERATED STRUCTURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

- A FUNDAMENTAL DIFFERENTIATING PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203

- STEP-BY-STEP ADAPTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

- EACH STEP IS ALWAYS HELPING TO ENHANCE THE WHOLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

- ALWAYS MAKING CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

- THE SEQUENCE OF UNFOLDING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

- EVERY PART UNIQUE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 323

- PATTERNS: GENERIC RULES FOR MAKING CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 341

- DEEP FEELING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369

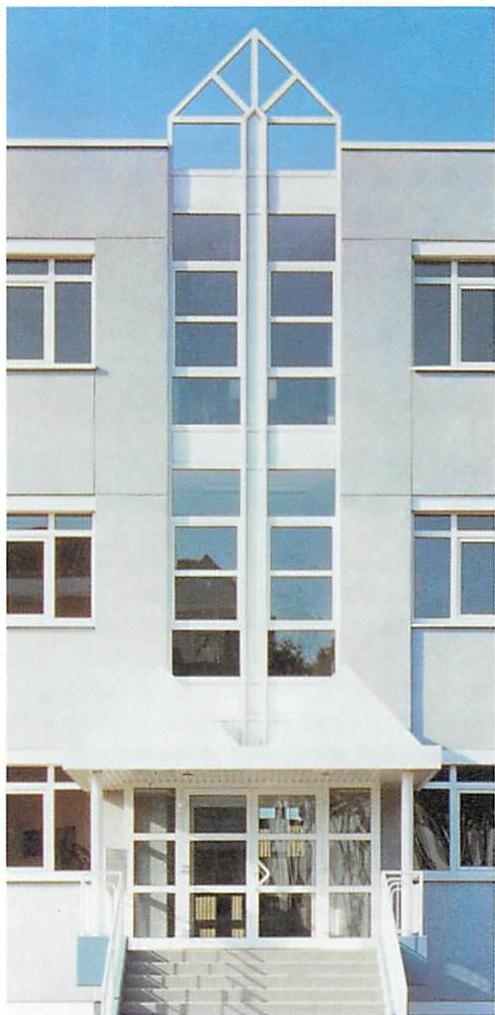

- EMERGENCE OF FORMAL GEOMETRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 401

- FORM LANGUAGE AND STYLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 431

- SIMPLICITY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 461

PART THREE: A NEW PARADIGM FOR PROCESS IN SOCIETY

- ENCOURAGING FREEDOM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 495

- MASSIVE PROCESS DIFFICULTIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 511

- THE SPREAD OF LIVING PROCESSES THROUGHOUT SOCIETY: MAKING THE SHIFT TO THE NEW PARADIGM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 531

- THE ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT IN THE THIRD MILLENNIUM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 551

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 565 APPENDIX: A SMALL EXAMPLE OF A LIVING PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 571

BOOK THREE: A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

PREFACE: LIVING PROCESSES REPEATED TEN MILLION TIMES. . . . . . 1

PART ONE

- OUR BELONGING TO THE WORLD: PART ONE. . . . . . . . . . 23

- OUR BELONGING TO THE WORLD: PART TWO . . . . . . . . . 41

PART TWO

- THE HULLS OF PUBLIC SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

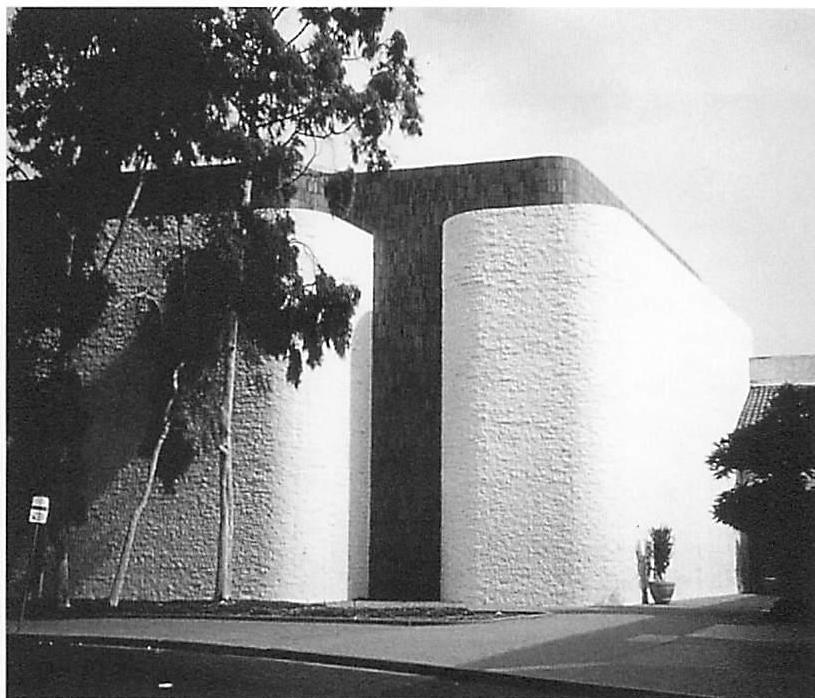

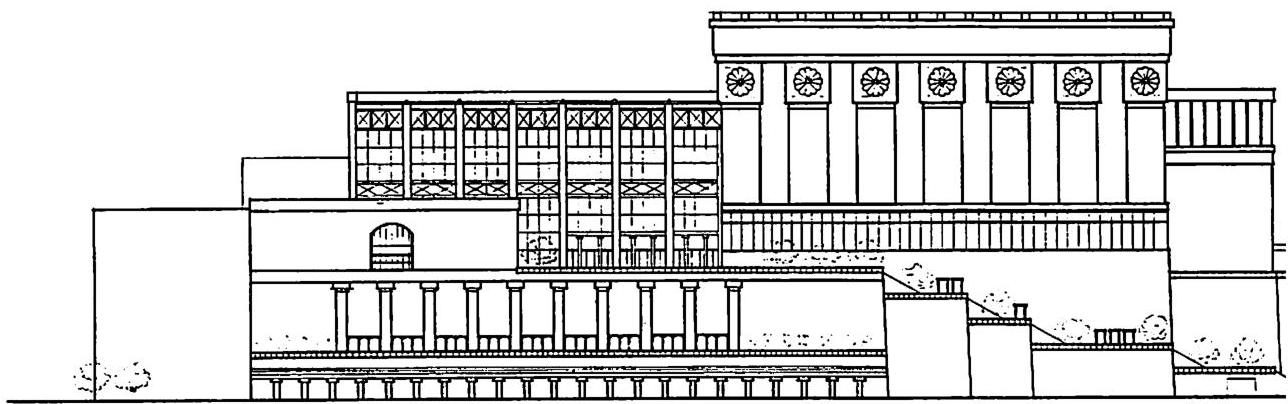

- LARGE PUBLIC BUILDINGS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

- THE POSITIVE PATTERN OF SPACE AND VOLUME IN THREE DIMENSIONS ON THE LAND. . . . . . . . . . . . 153

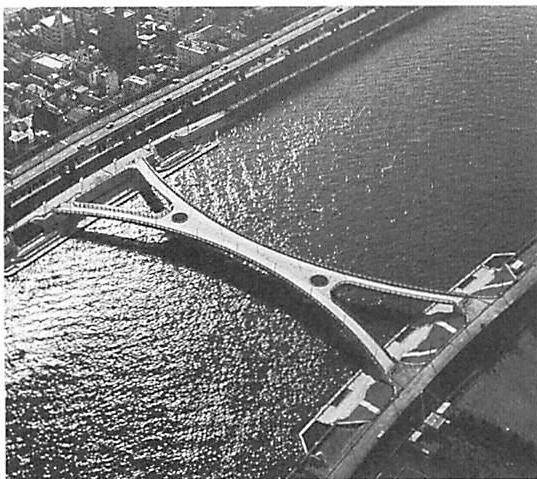

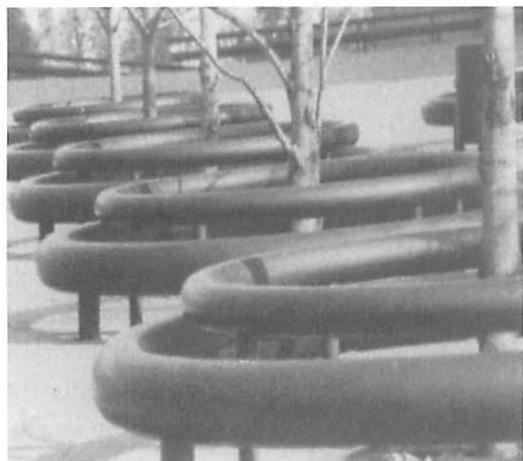

- POSITIVE SPACE IN ENGINEERING STRUCTURE AND GEOMETRY. . . 191

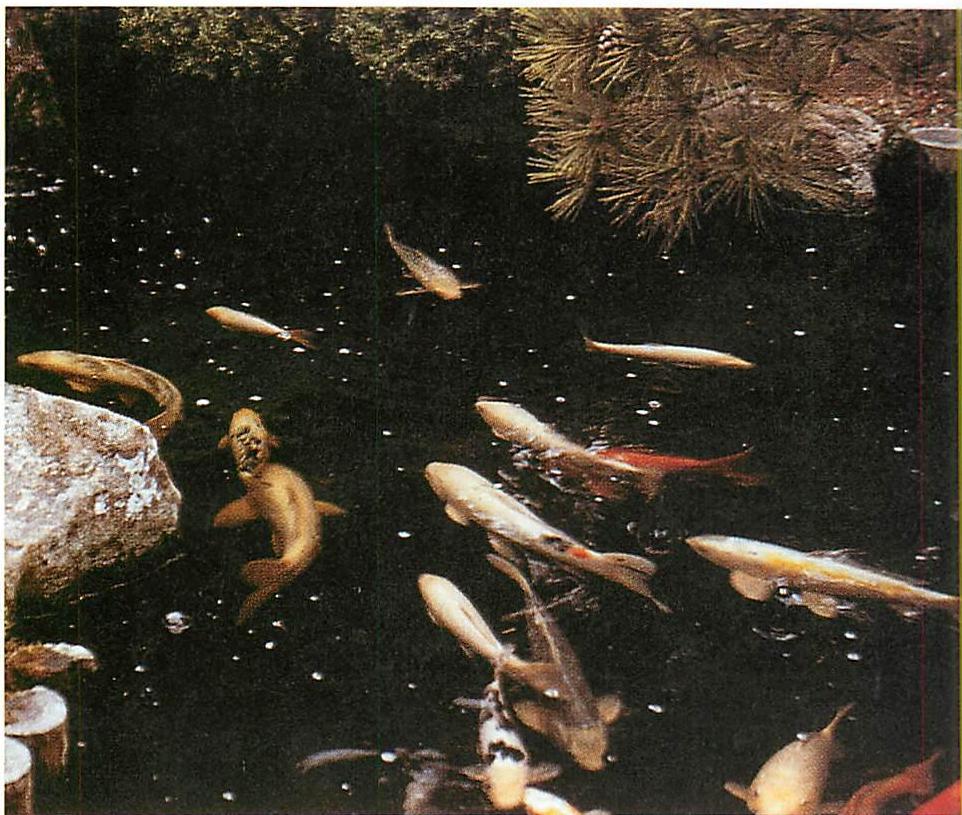

- THE CHARACTER OF GARDENS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

PART THREE

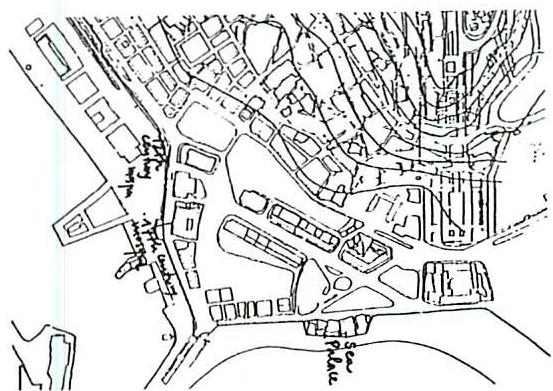

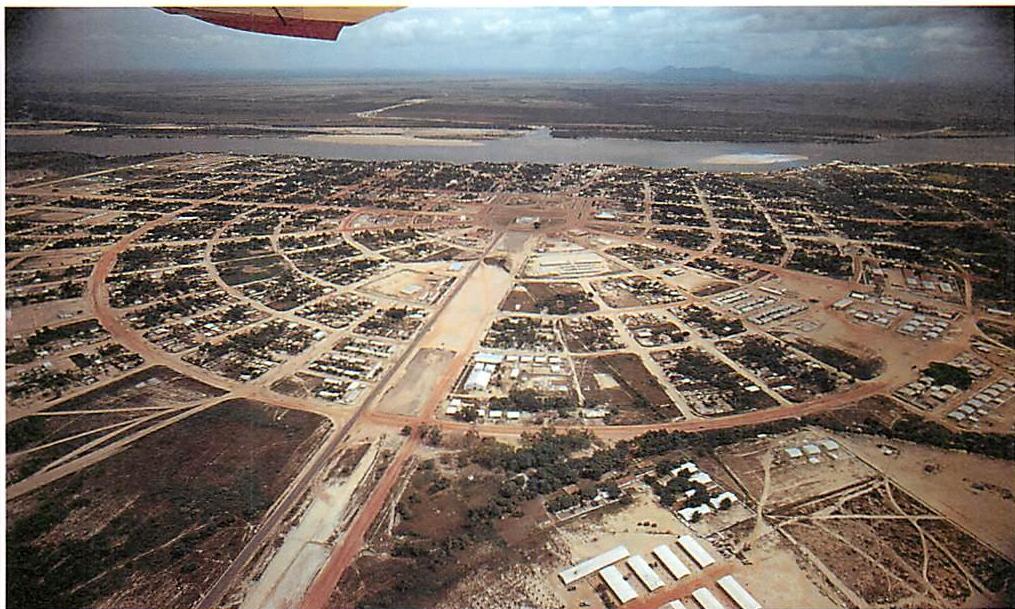

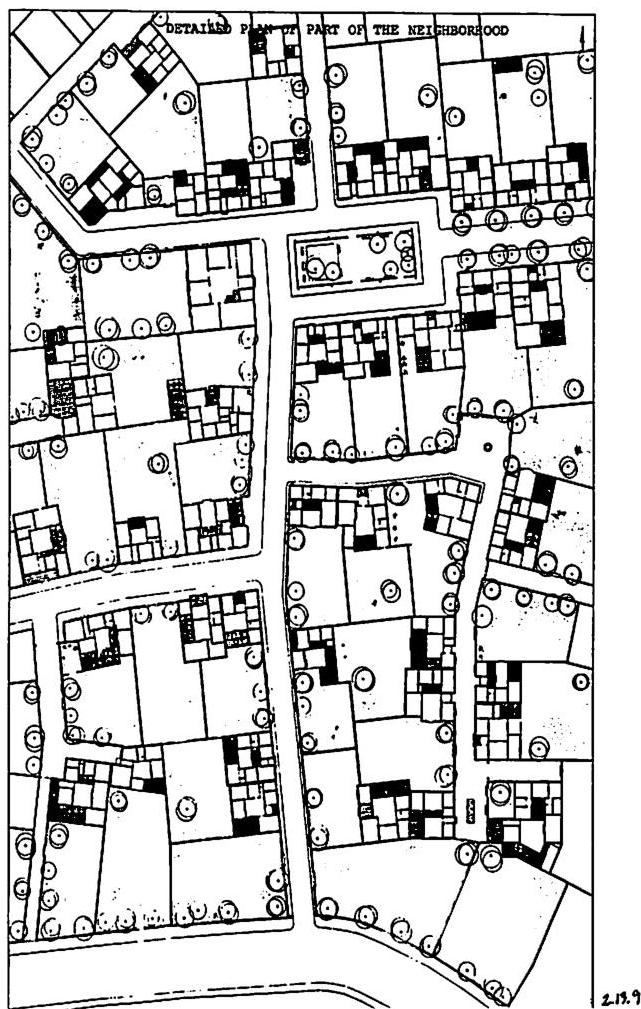

- PEOPLE FORMING A COLLECTIVE VISION FOR THEIR NEIGHBORHOOD. 257

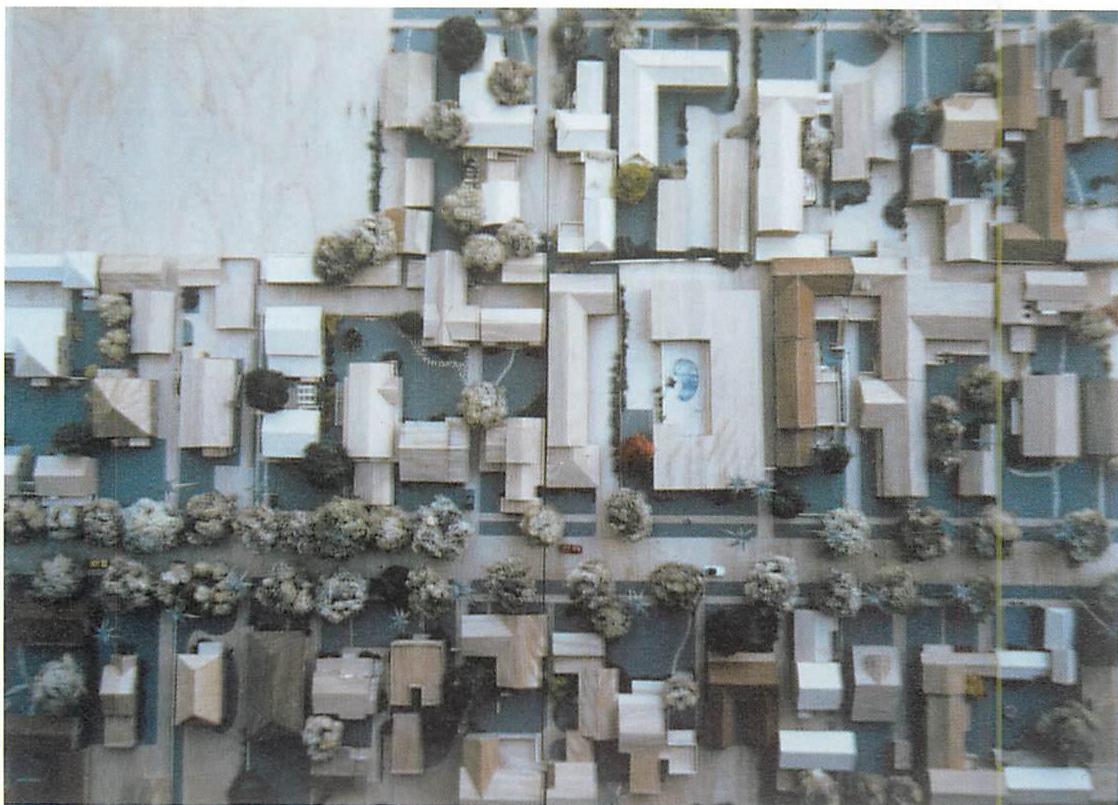

- THE RECONSTRUCTION OF AN URBAN NEIGHBORHOOD . . . . . 283

- HIGH DENSITY HOUSING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 311

- NECESSARY FURTHER DYNAMICS OF ANY NEIGHBORHOOD WHICH COMES TO LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 333

PART FOUR

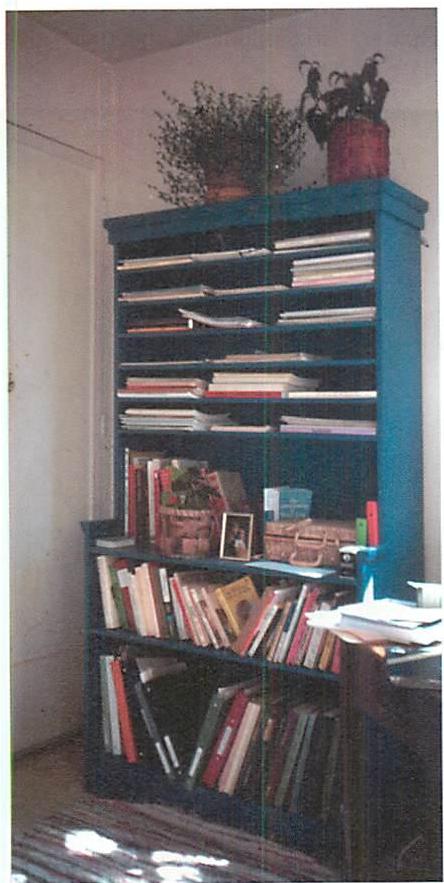

- THE UNIQUENESS OF PEOPLE'S INDIVIDUAL WORLDS . . . . . . 361

- THE CHARACTER OF ROOMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 411

PART FIVE

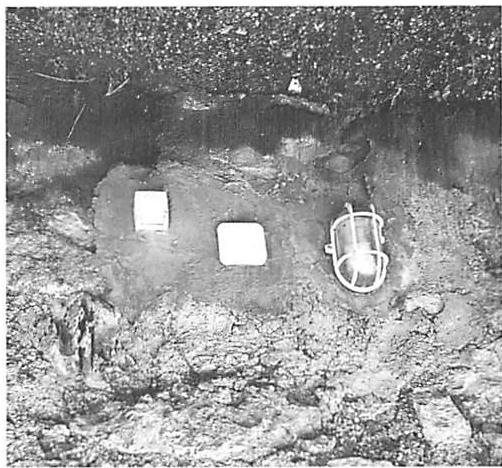

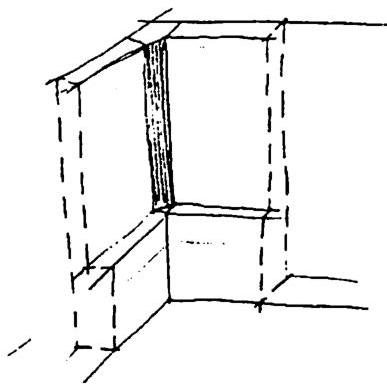

- CONSTRUCTION ELEMENTS AS LIVING CENTERS. . . . . . . . . 447

- ALL BUILDING AS MAKING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 481

- CONTINUOUS INVENTION OF NEW MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES . . 517

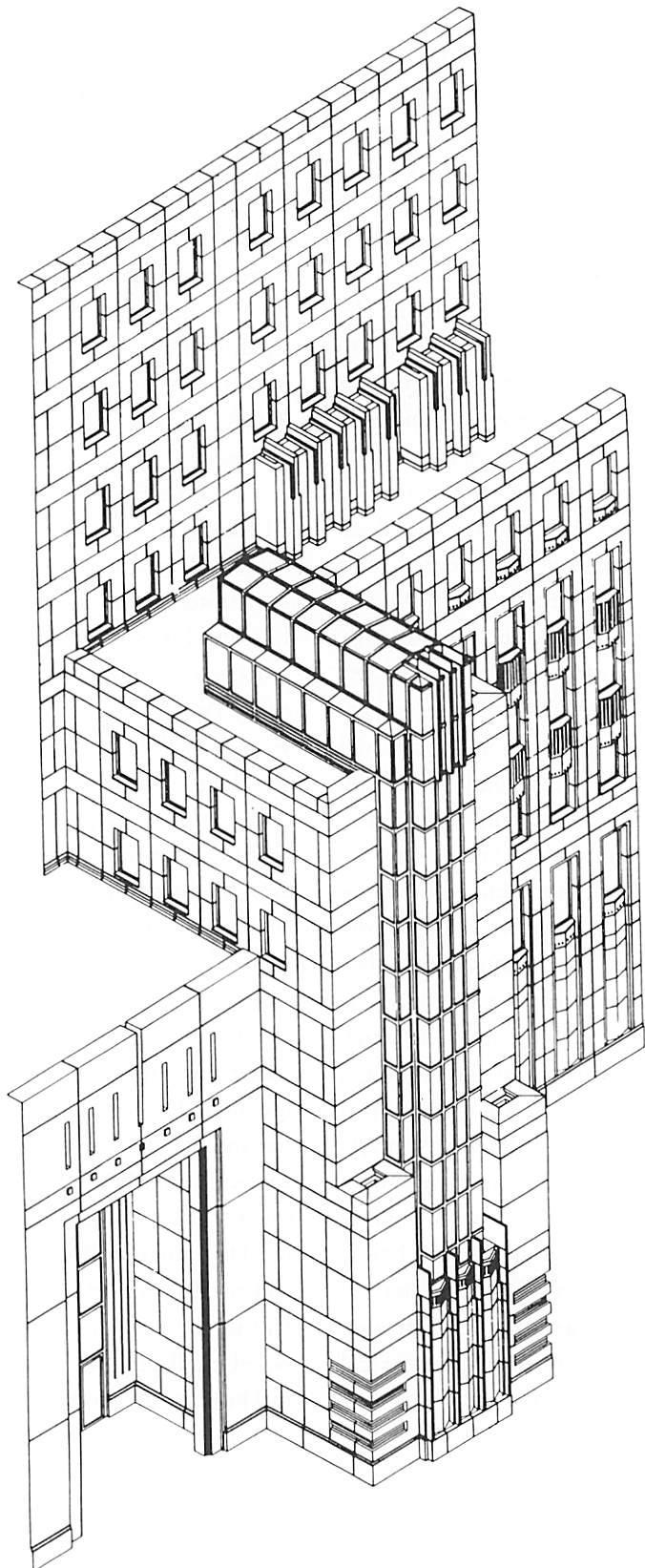

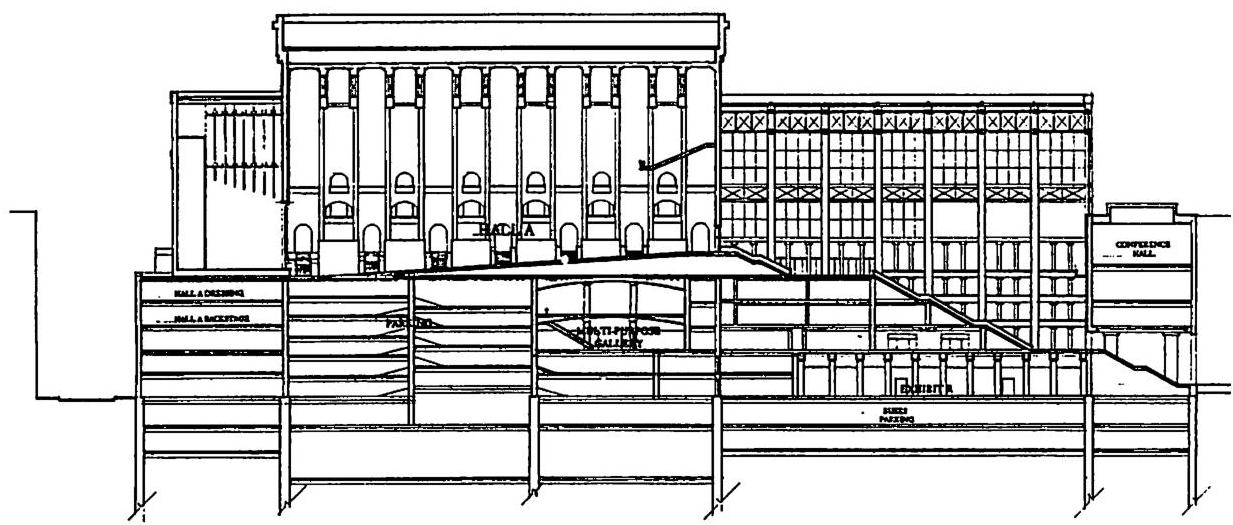

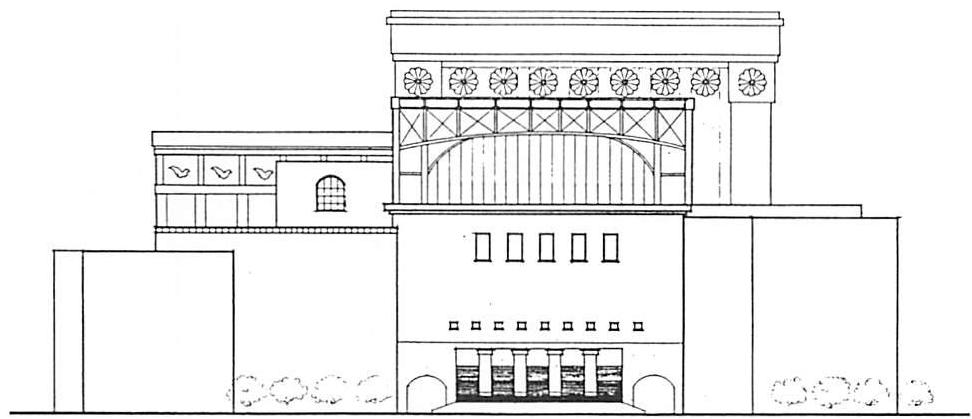

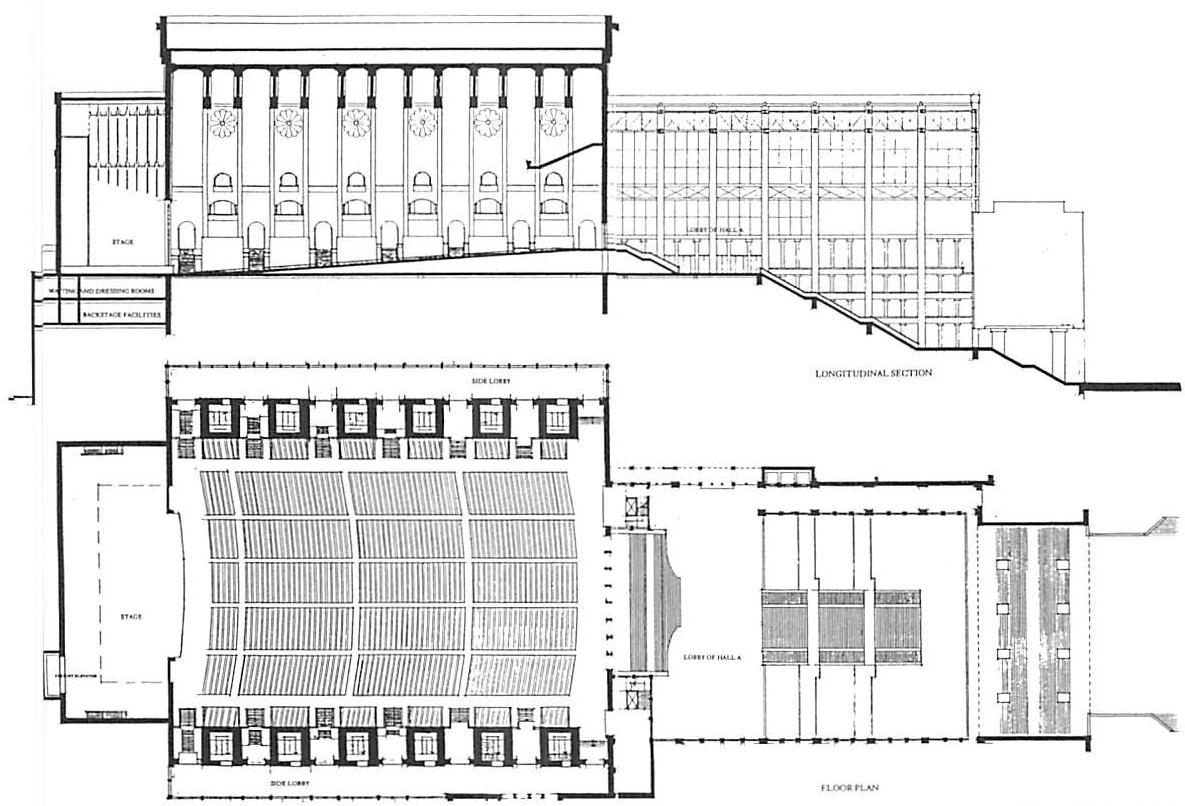

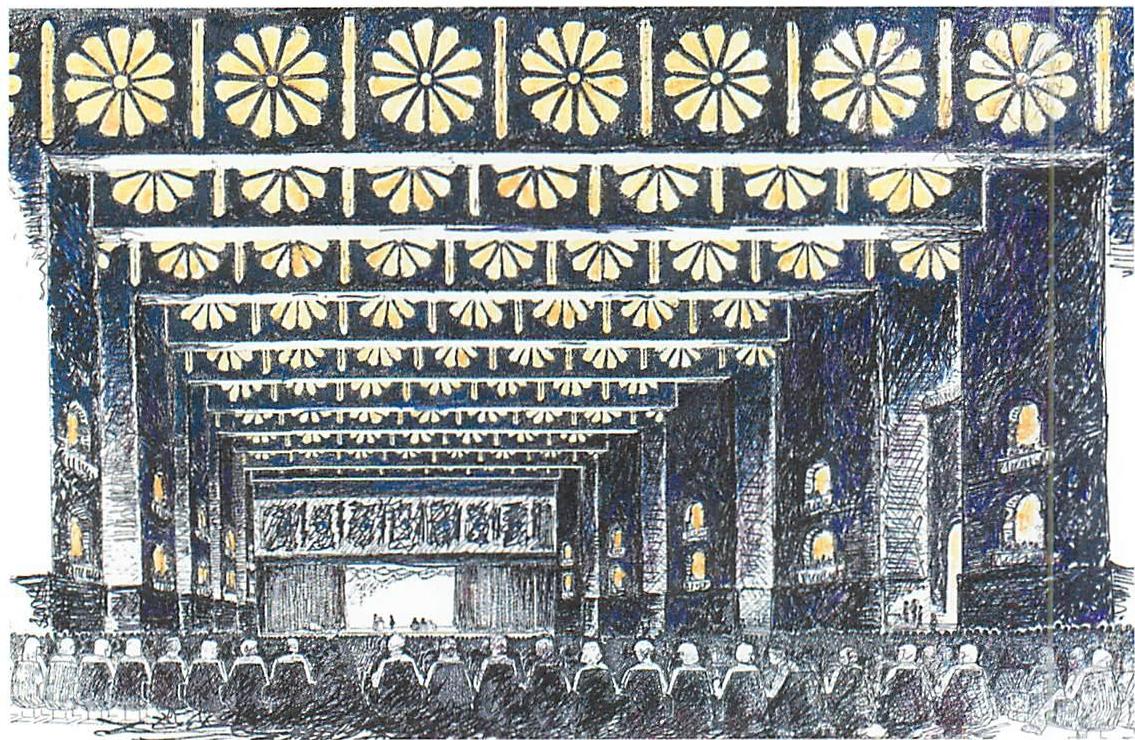

- PRODUCTION OF GIANT PROJECTS . . . . . . . . . . . . 561

PART SIX

- ORNAMENT AS A PART OF ALL UNFOLDING . . . . . . . . . 579

- COLOR WHICH UNFOLDS FROM THE CONFIGURATION . . . . . 615

THE MORPHOLOGY OF LIVING ARCHITECTURE: ARCHETYPAL FORM. . . 639 CONCLUSION: THE WORLD CREATED AND TRANSFORMED . . . . . 675 APPENDIX ON NUMBER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 683

BOOK FOUR: THE LUMINOUS GROUND

PREFACE: TOWARDS A NEW CONCEPTION OF THE NATURE OF MATTER . . . 1

PART ONE

- OUR PRESENT PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . . . . . . . 9

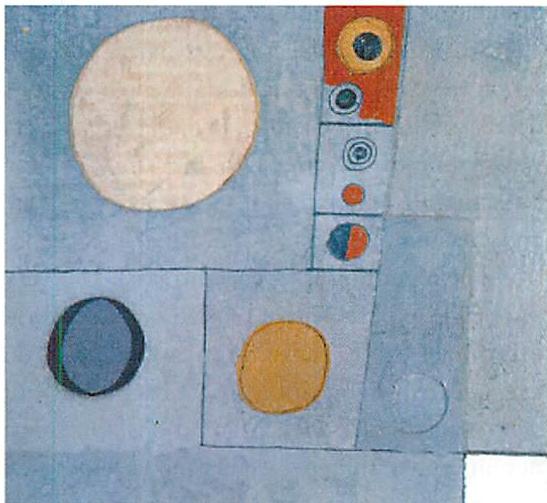

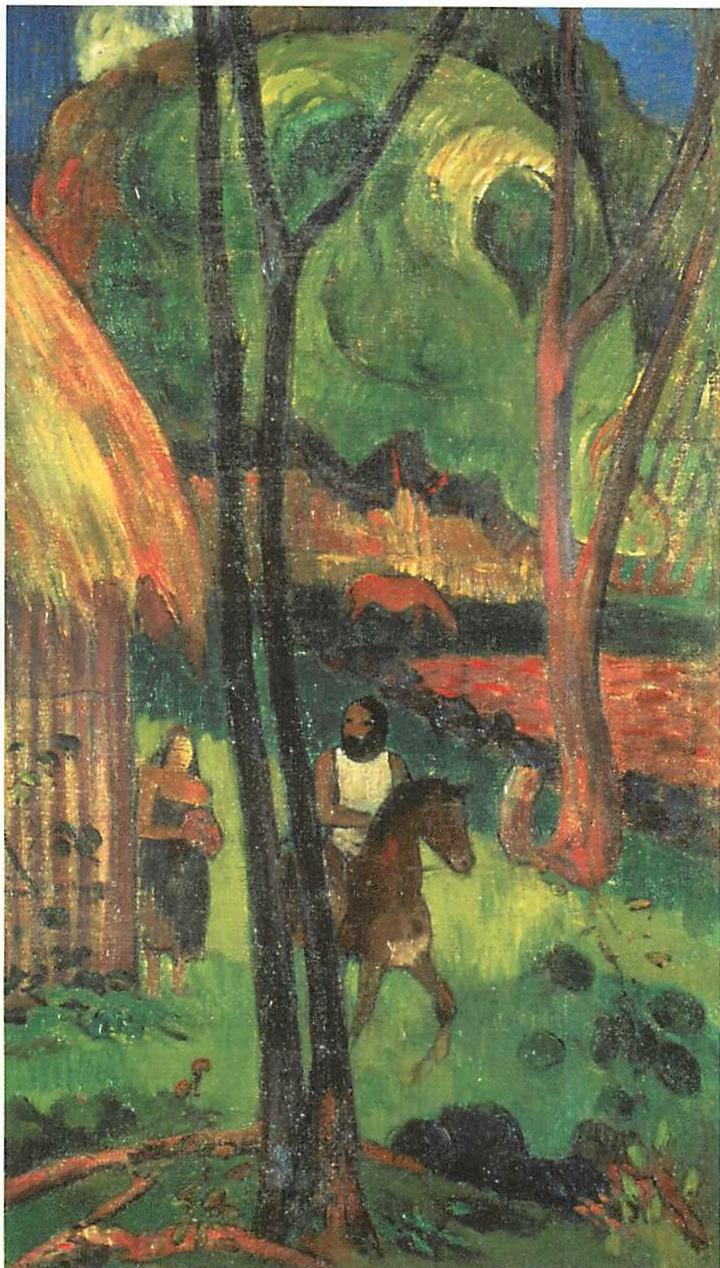

- CLUES FROM THE HISTORY OF ART. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

- THE EXISTENCE OF AN "1" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

- THE TEN THOUSAND BEINGS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

- THE PRACTICAL MATTER OF FORGING A LIVING CENTER. . . . . 111

MID-BOOK APPENDIX: RECAPITULATION OF THE ARGUMENT. . . . . 135

PART TWO

- THE BLAZING ONE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

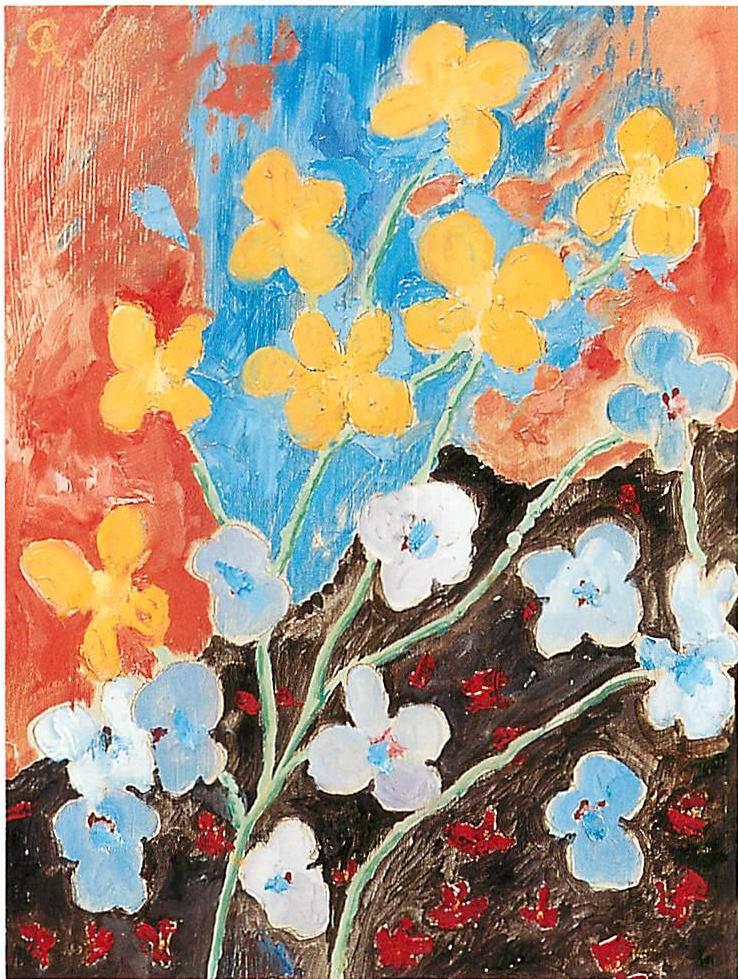

- COLOR AND INNER LIGHT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

- THE GOAL OF TEARS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

- MAKING WHOLENESS HEALS THE MAKER. . . . . . . . . . 261

- PLEASING YOURSELF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271

- THE FACE OF GOD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 301

CONCLUSION TO THE FOUR BOOKS

A MODIFIED PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . . . . . . . 317 EPILOGUE: EMPIRICAL CERTAINTY AND ENDURING DOUBT . . . . 339 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 345

I DEDICATE THESE FOUR BOOKS TO MY FAMILY:

TO MY BELOVED MOTHER, WHO DIED MANY YEARS AGO;

TO MY DEAR FATHER, WHO HAS ALWAYS HELPED ME AND INSPIRED ME;

TO MY DARLINGS LILY AND SOPHIE;

AND TO MY DEAR WIFE PAMELA WHO GAVE THEM TO ME,

AND WHO SHARES THEM WITH ME.

THESE BOOKS ARE A SUMMARY OF WHAT I HAVE UNDERSTOOD ABOUT

THE WORLD IN THE SIXTY-THIRD YEAR OF MY LIFE.

THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THE CONCEPT OF LIVING STRUCTURE

In order to provide a background for Book 2, it is necessary to summarize what I have, I believe, accomplished in Book I, THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE.

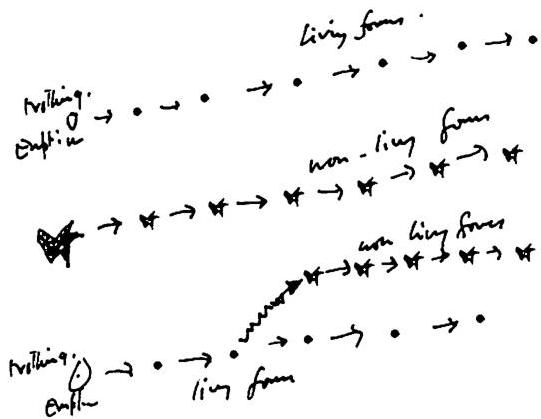

The basic idea is this: Throughout the world, in the organic as in the inorganic, it is possible to make a distinction between living structure and non-living structure. In nature, most structures which appear (whether organic or inorganic) are living structures to a fairly high degree. This is a class of structures which does not pertain exclusively to organisms or organic life. It is a more general class of structures, existing within the very much vaster class of all possible three-dimensional structures.

As I use it, the term "living" applied to structure is always a matter of degree. Strictly speaking, every structure has some degree of life. The main accomplishment of Book I is in making this distinction precise, in providing empirical methods for observing and measuring degree of life as it occurs in different structures. Perhaps most important, I gave in Book I a partly mathematical account of living structure, so that we may see the content of living structure, its functional and geometric order, as an established and objective feature of reality.

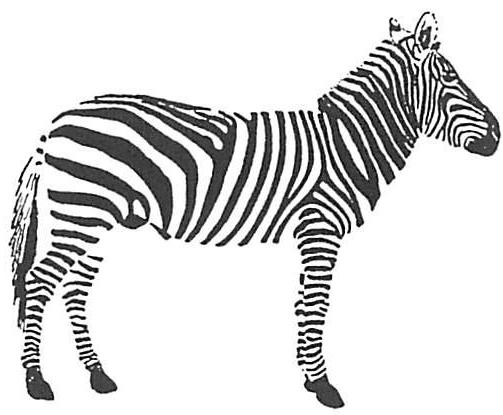

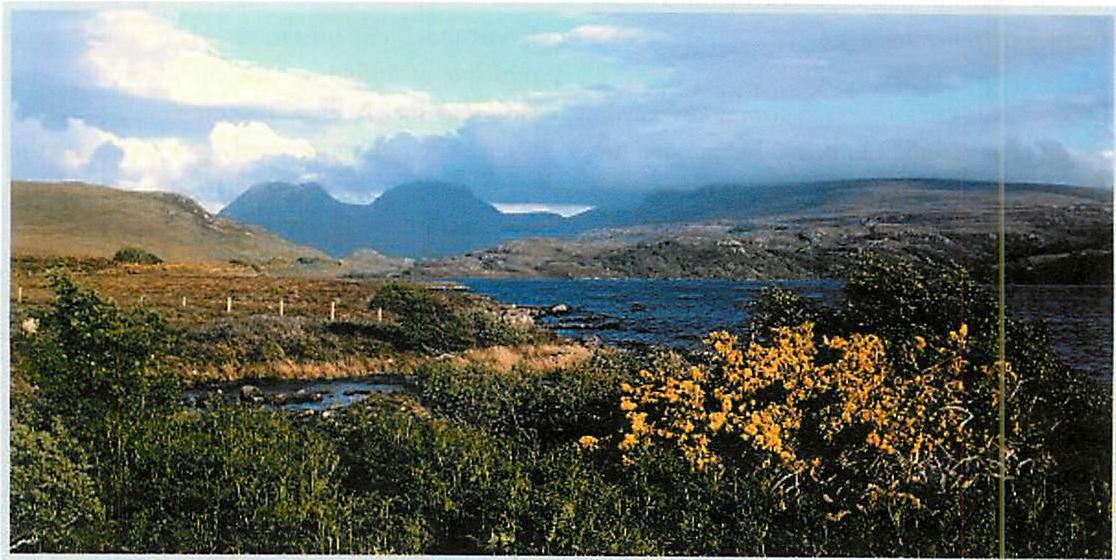

In nature, almost everything has living structure: waves, sand, rocks, forests, thunderstorms, birds, snakes, and moss. That is why, I think, scientists have not previously drawn attention to the existence of the class of living structures, nor to the distinction between living and non-living structure. It has not, in physics, or geology, or biology, or chemistry, so far been a necessary distinction.

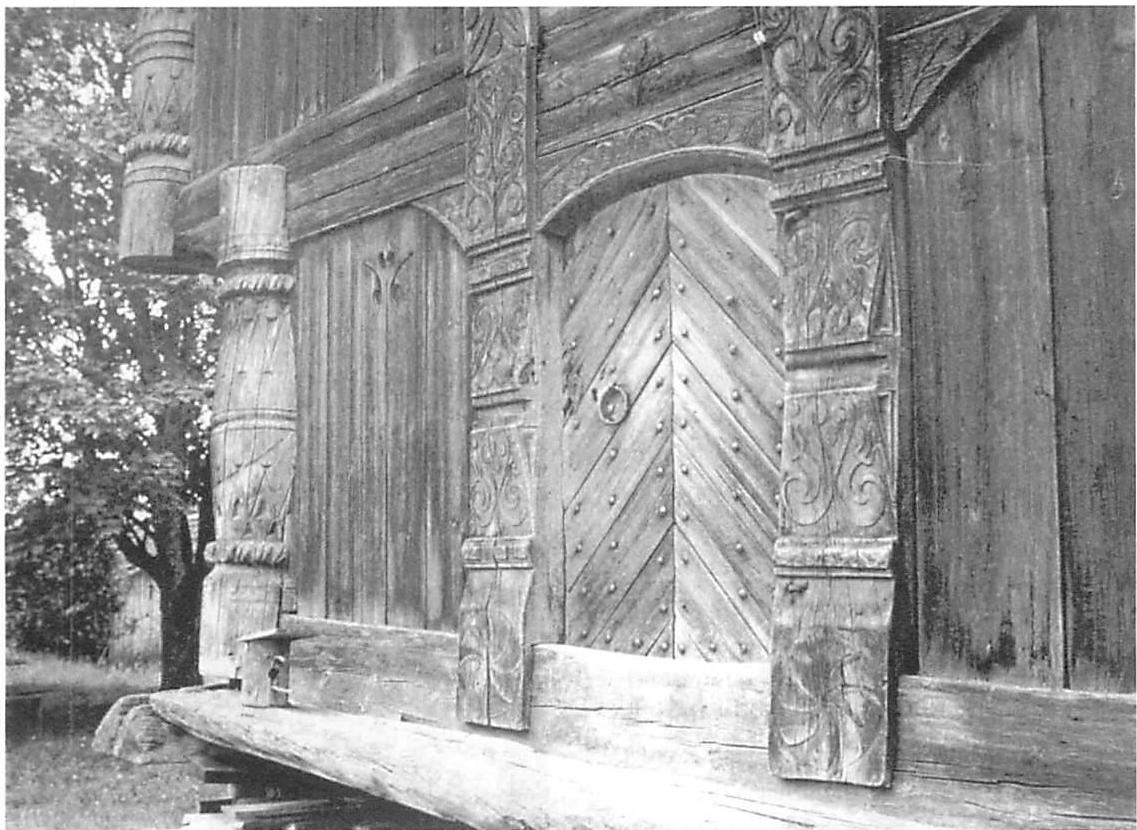

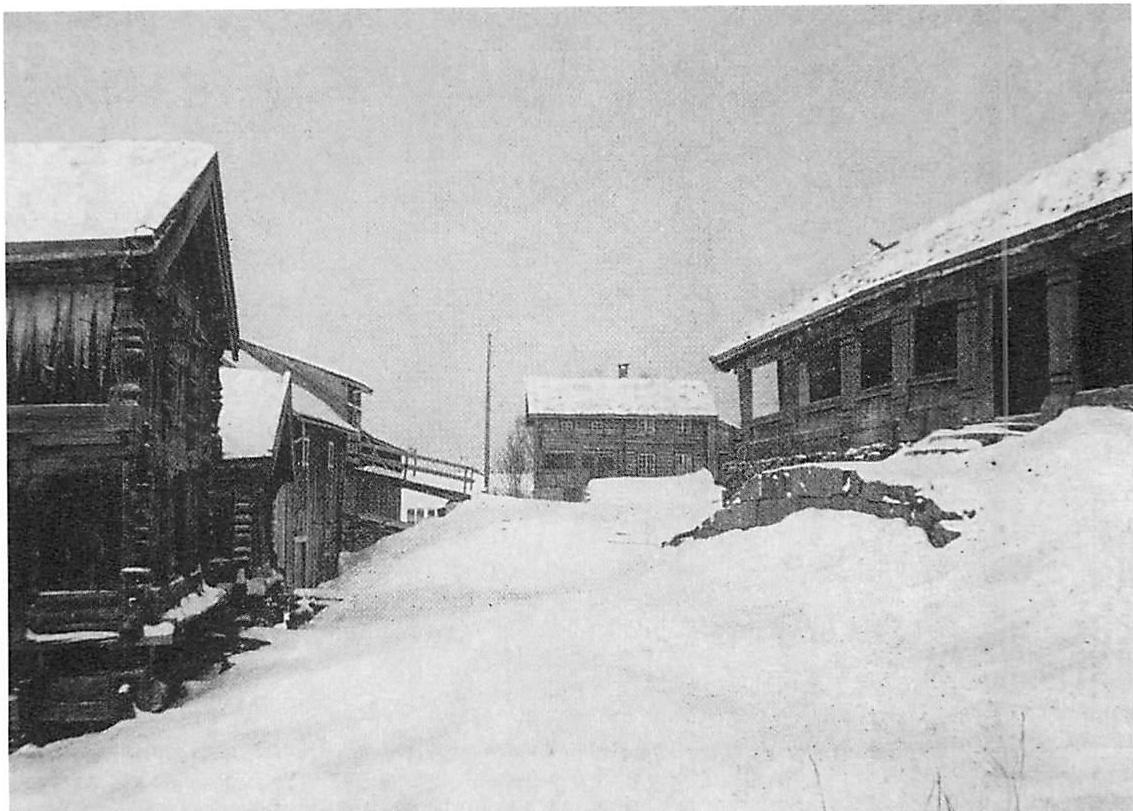

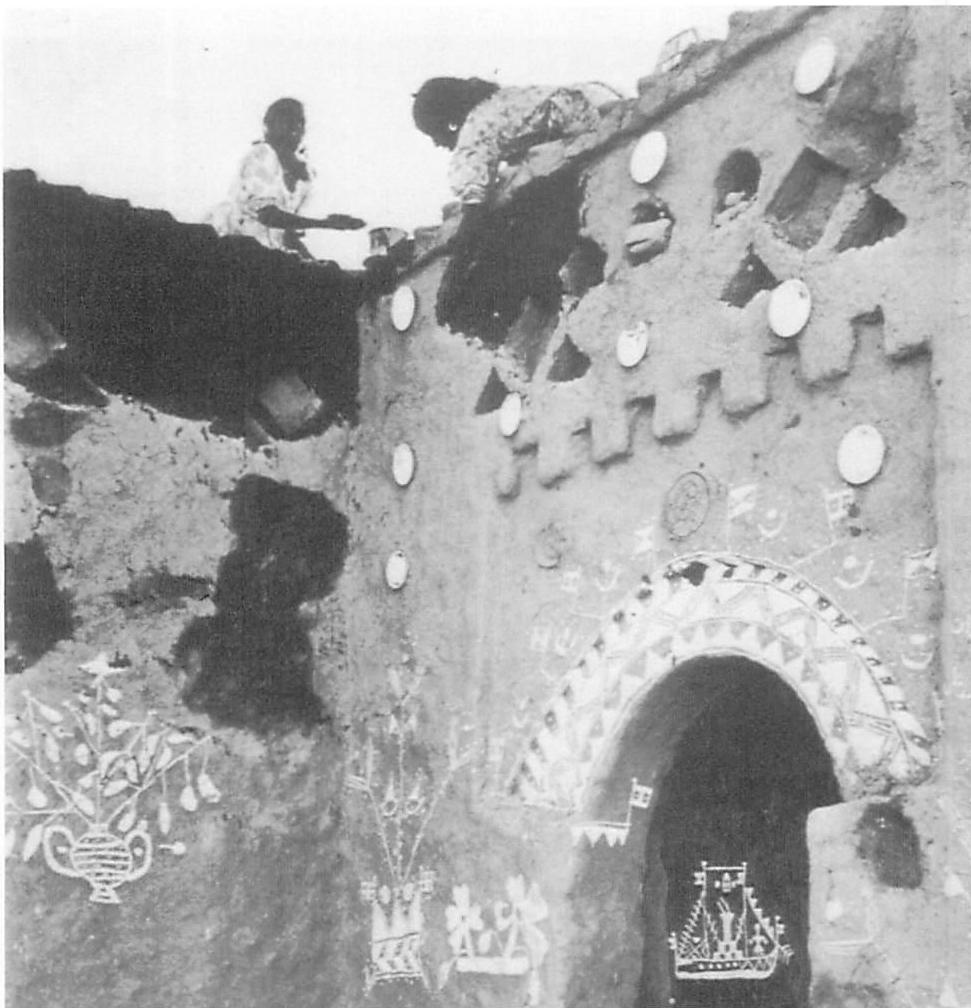

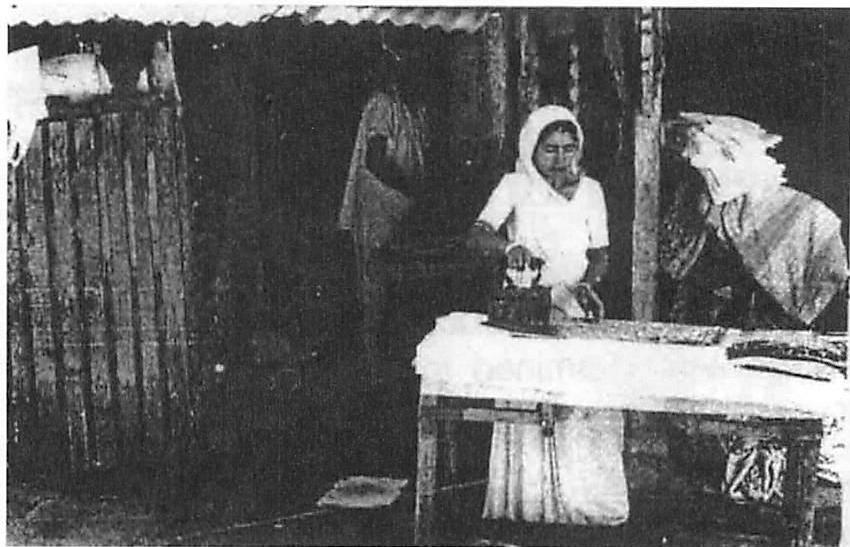

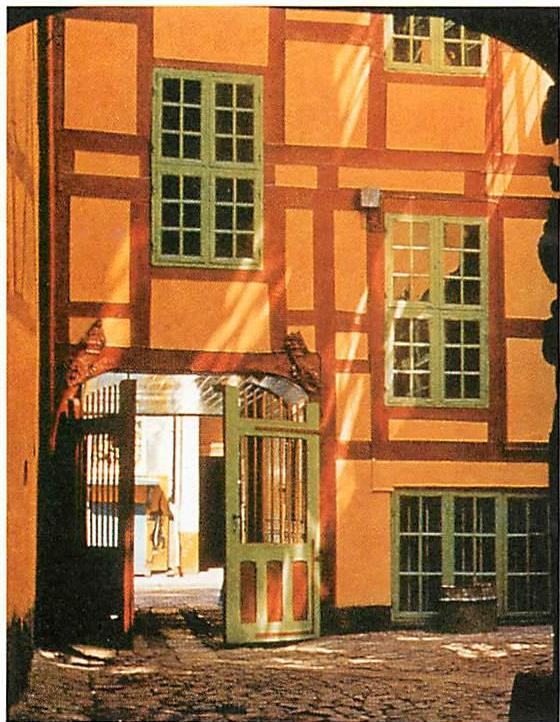

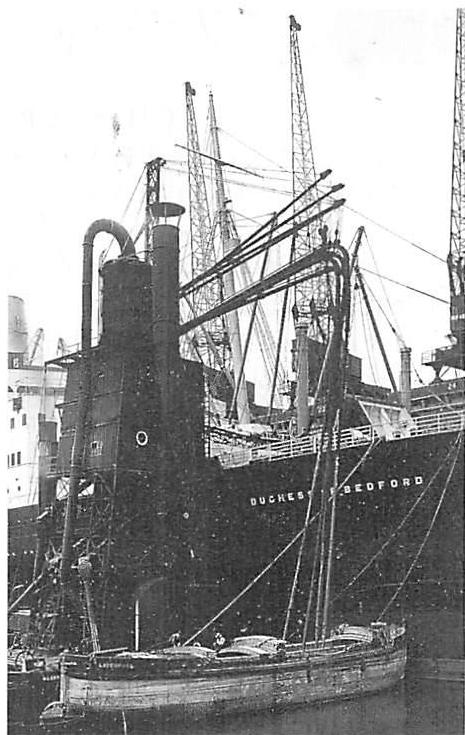

In primitive society builders also needed no distinction, because within the processes available to them, nearly everything made by people had living structure, just as systems in nature do. By and large, traditional builders, even as recently as a hundred years ago, also still made buildings, fields, and artifacts which had living structure.

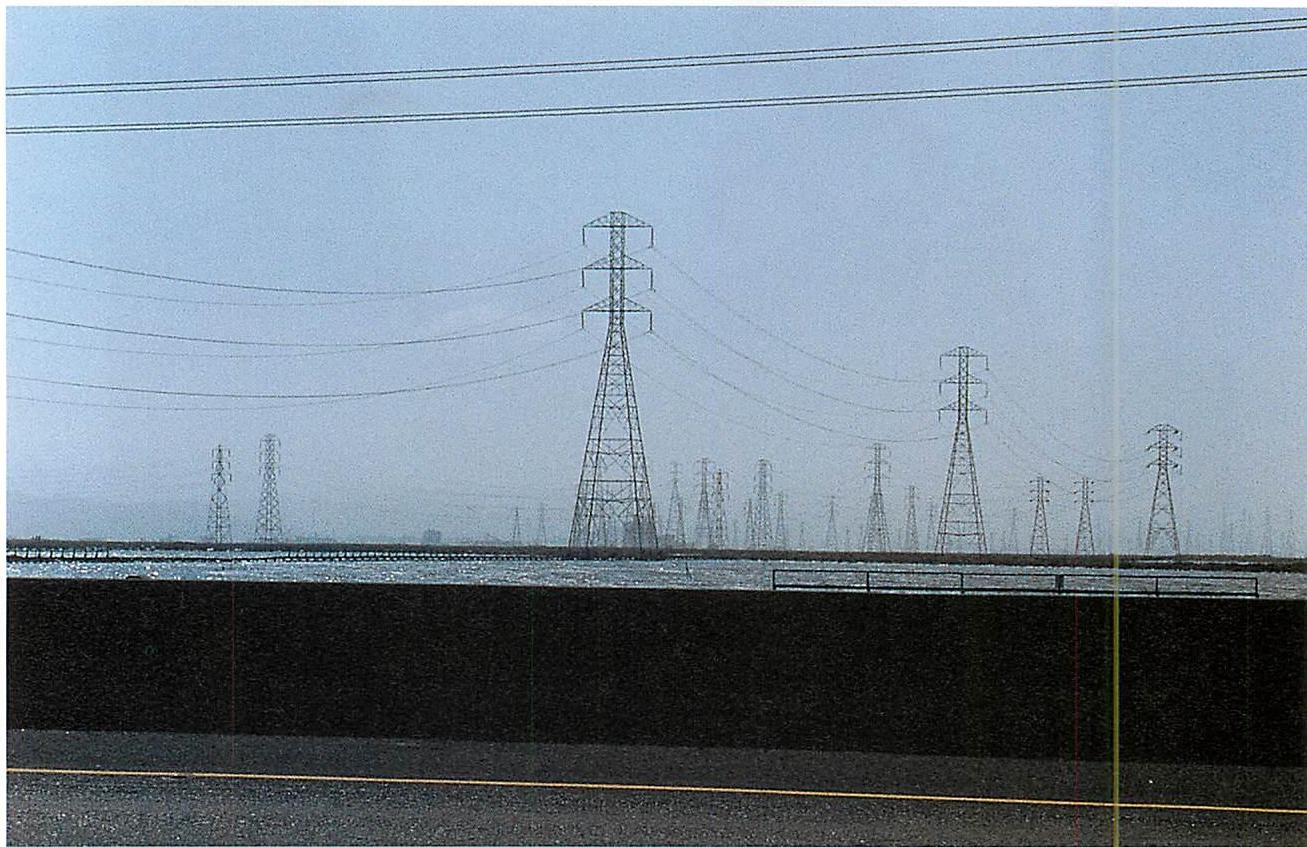

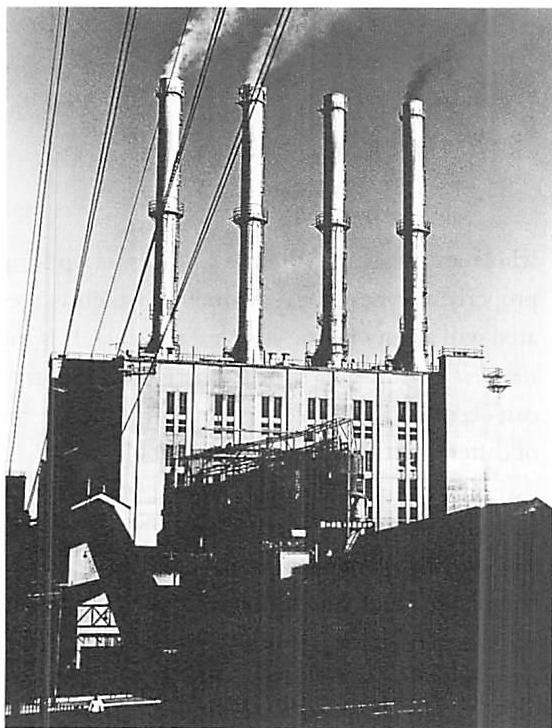

But in the past century, we have, for the first time, become able to conceive, design, make, manufacture, and produce non-living structure: kinds of things, arrangements of matter, buildings, roads, artifacts which do not belong to the class of living structures and which, for the first time, focus our attention on the distinction.

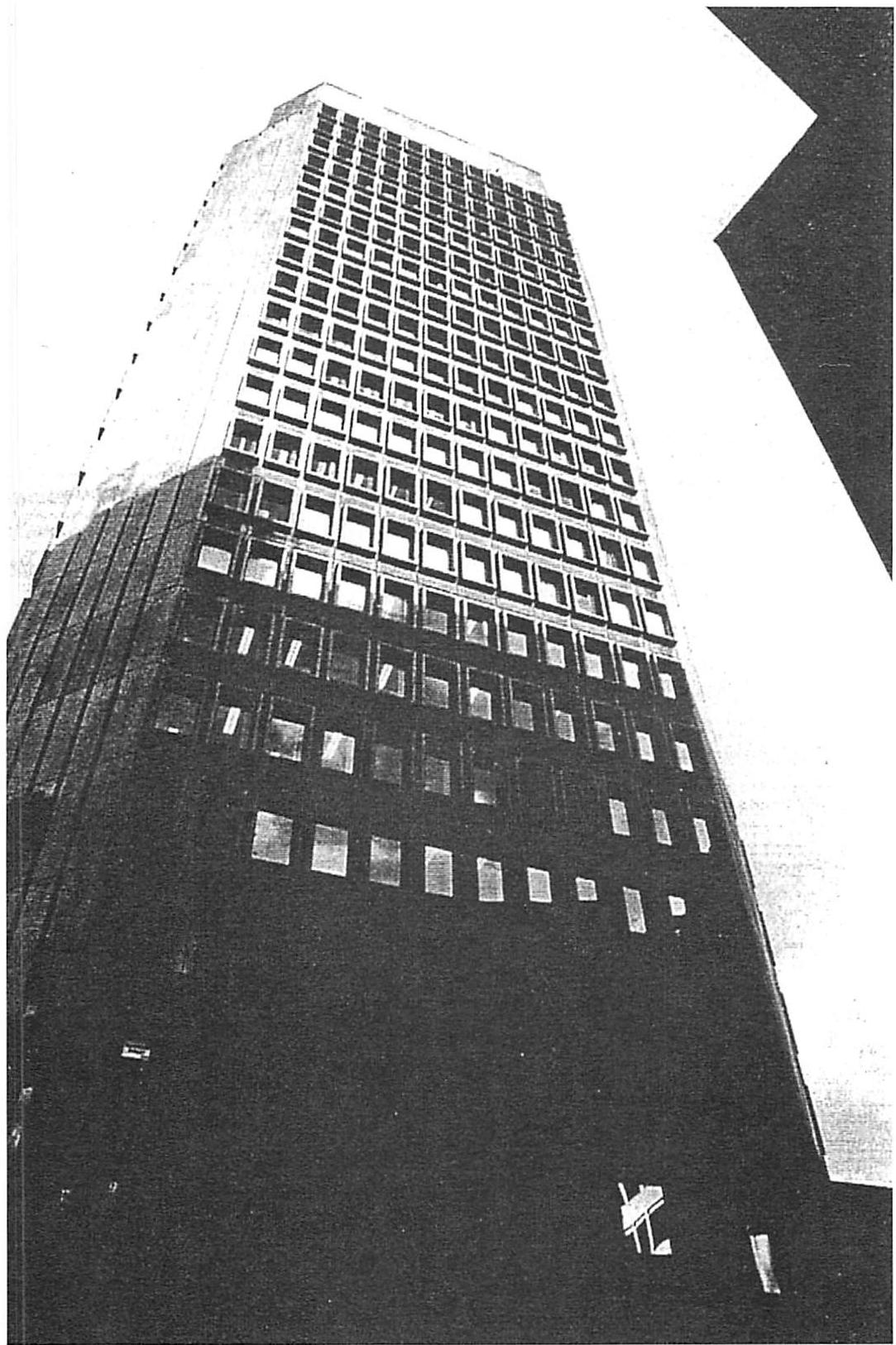

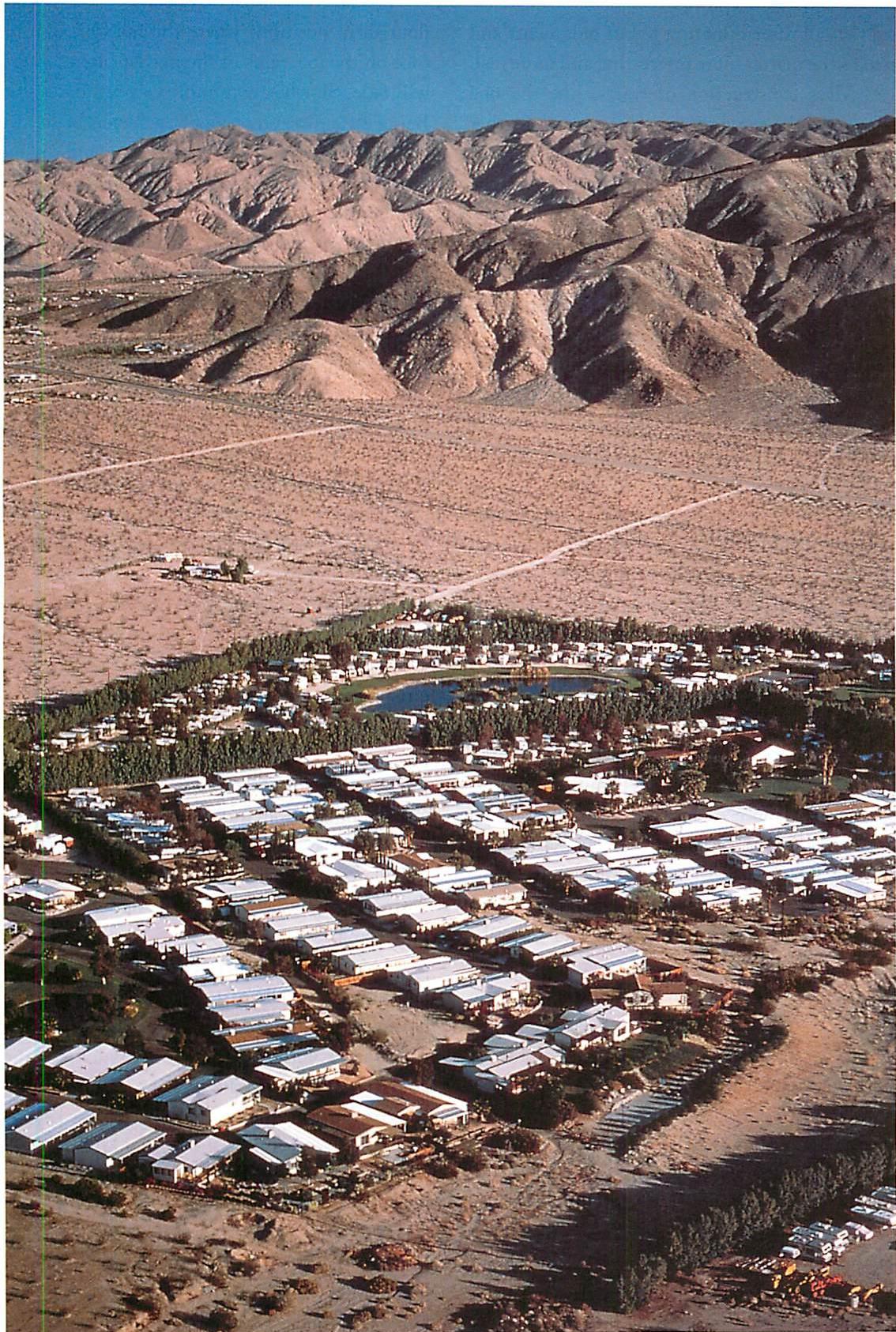

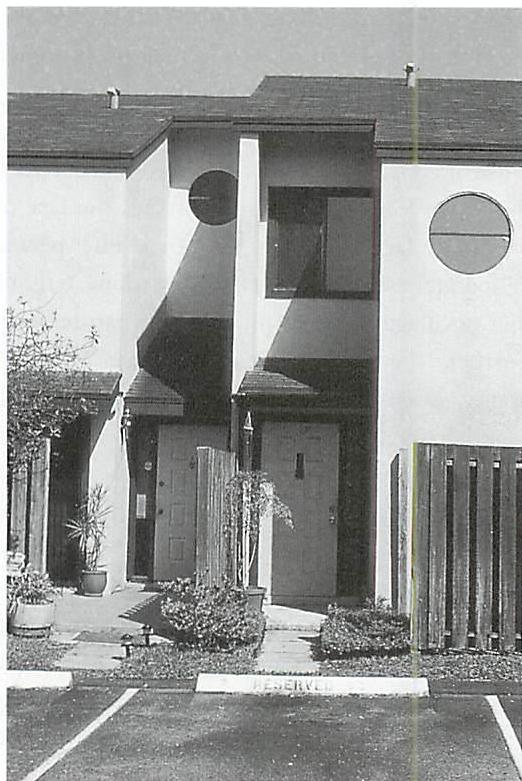

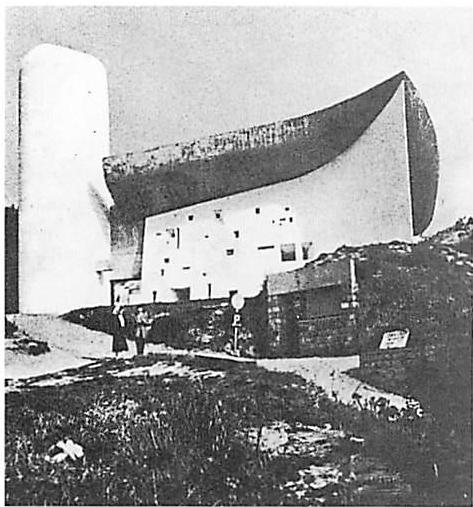

Thus the objects, buildings, and landscapes created by human beings in the past century have, very often, been outside the class of living structures. More exactly, they are often systems with significantly low levels of living structure, much lower than occurs in nature. That is something new in human history.

For reasons which will become clear in the next chapters, I believe that many of these new artifacts and buildings — including, for instance, the apparently harmless developer-inspired motels of our era or our mass housing projects — are structures which can be thought, invented, created artificially, but they cannot be generated by a nature-like process at all. Thus they are, structurally speaking, monsters. They are not merely unappealing and strange. They belong, objectively, to a class of non-living structures, or less living structures, and have thus, for the first time, introduced a type of structure on earth which nature itself could not, in principle, create.

It is this event which has stimulated my investigation into these structures, and encouraged me to attempt a definition of the difference between living and non-living structure. The distinction compels attention because — if the arguments I have put forward in Book I are legitimate — it is important that we, as a people on Earth, learn to create our towns, buildings and landscapes so that they too — like nature — are living structures, and so that our artificial world is then a nature-like system. As I have suggested in Book I, the consequences of living our daily lives and maintaining human society in a world composed chiefly of non-living structure, are nearly catastrophic.

But I am jumping ahead of myself, since

what I have just said already depends on the conclusions of this book. My present starting point is simply this: there is such a thing as living structure, and there is an objective distinction between systems which have relatively more living structure and systems which have relatively less living structure.

The distinction has been brought to the fore by the history of zoth-century design and construction, which forced our attention — for the first time — on the fact that not all structures made by human beings are living ones.

The question is, How is living structure to be made by human beings? What kind of human-inspired processes can create living structure?

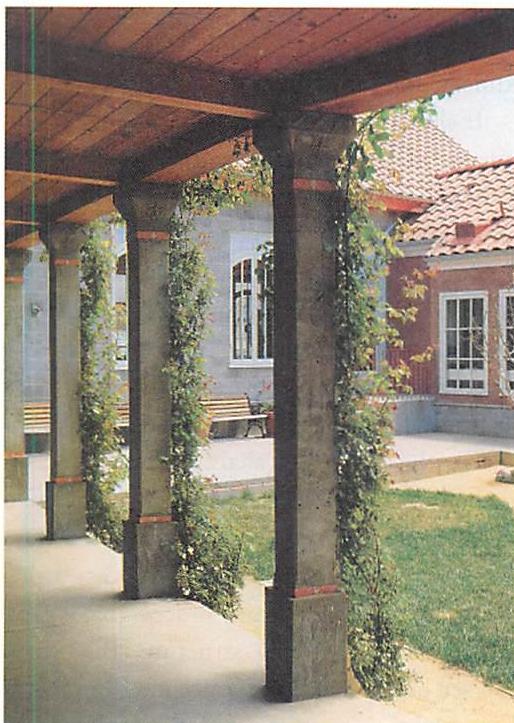

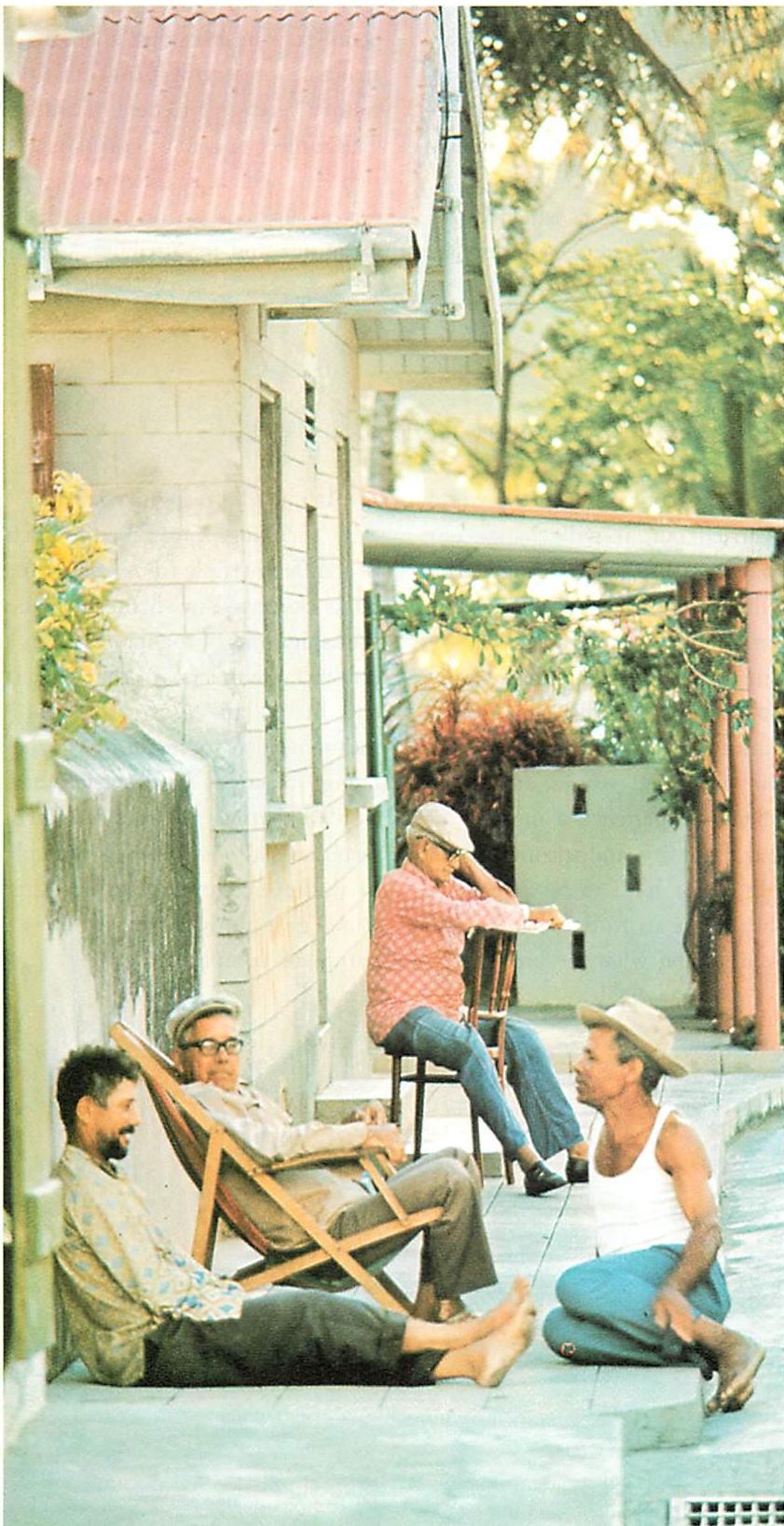

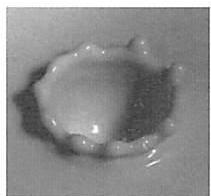

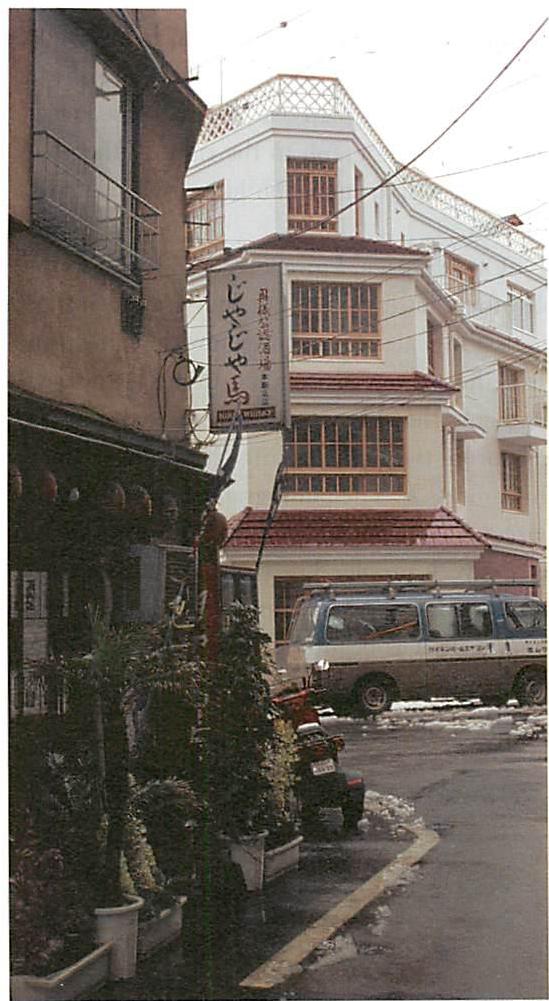

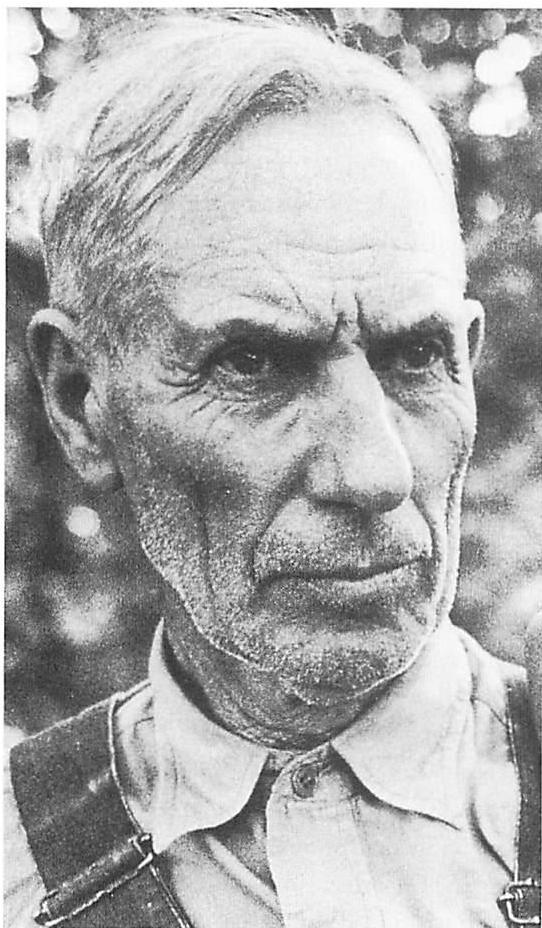

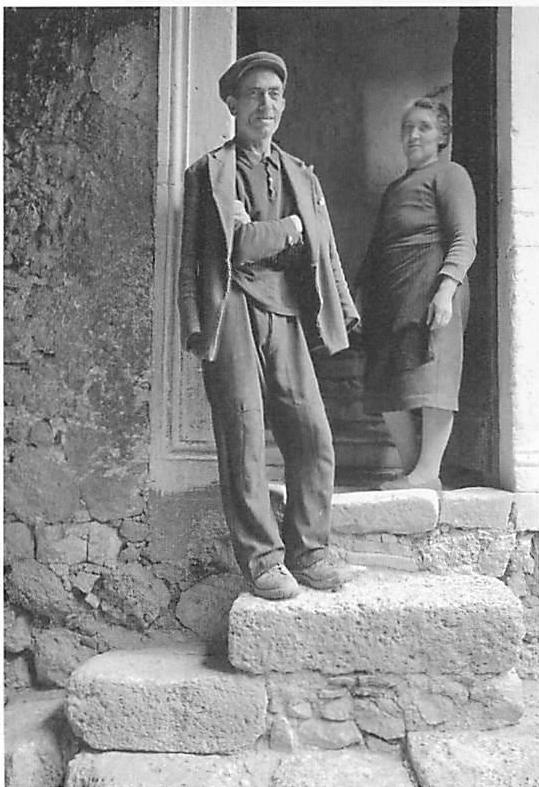

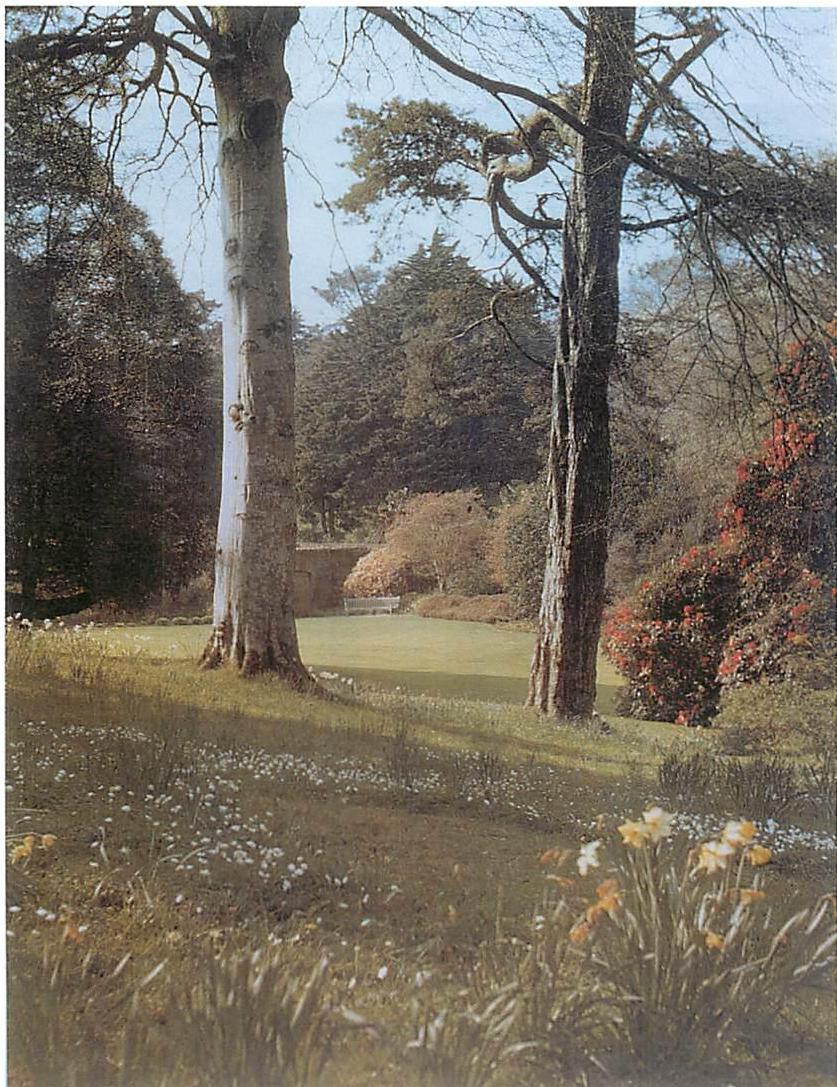

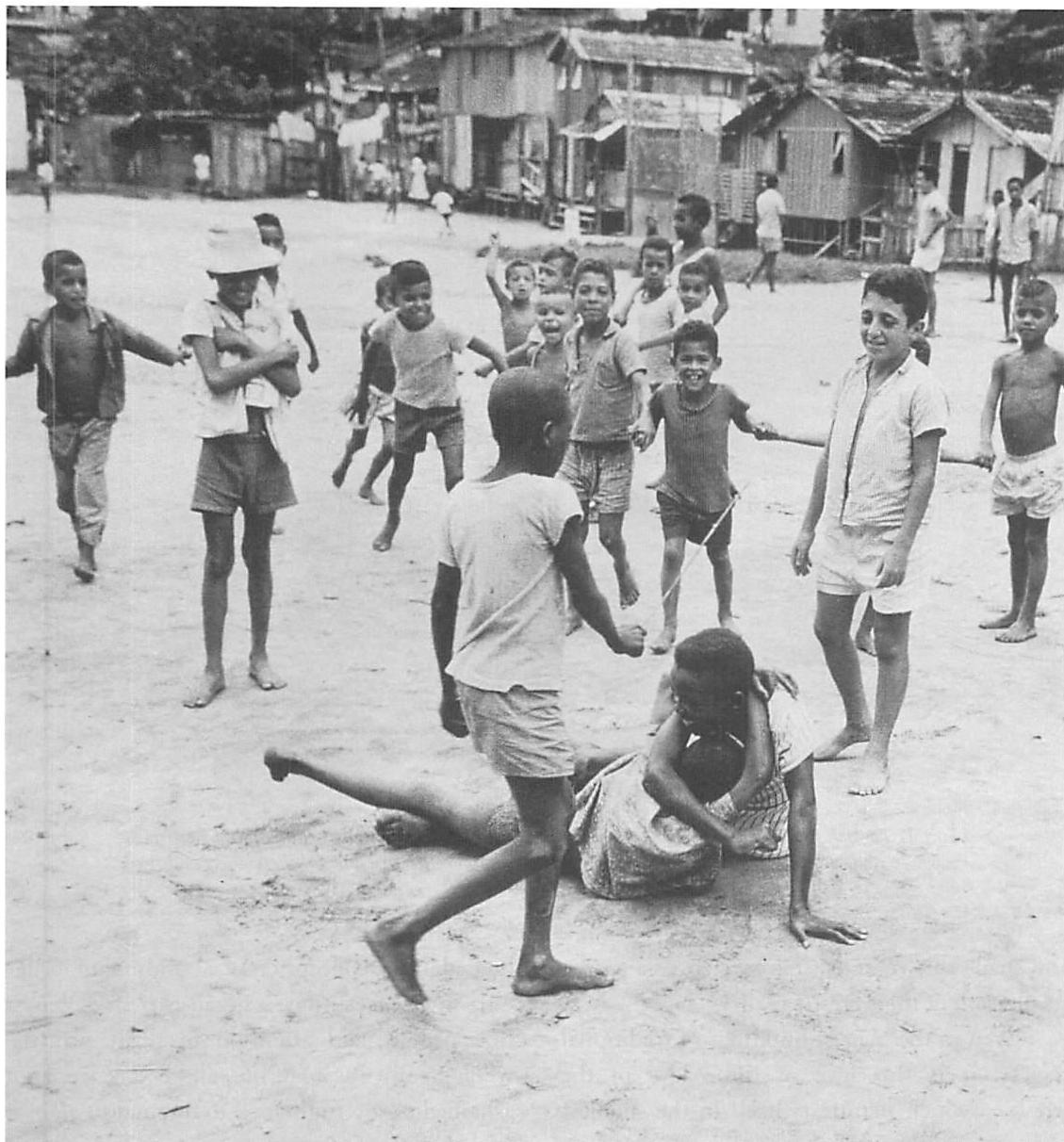

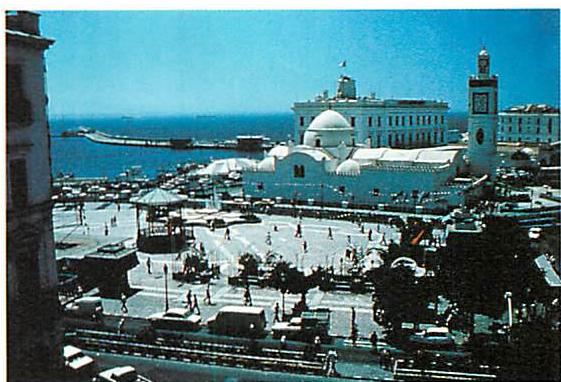

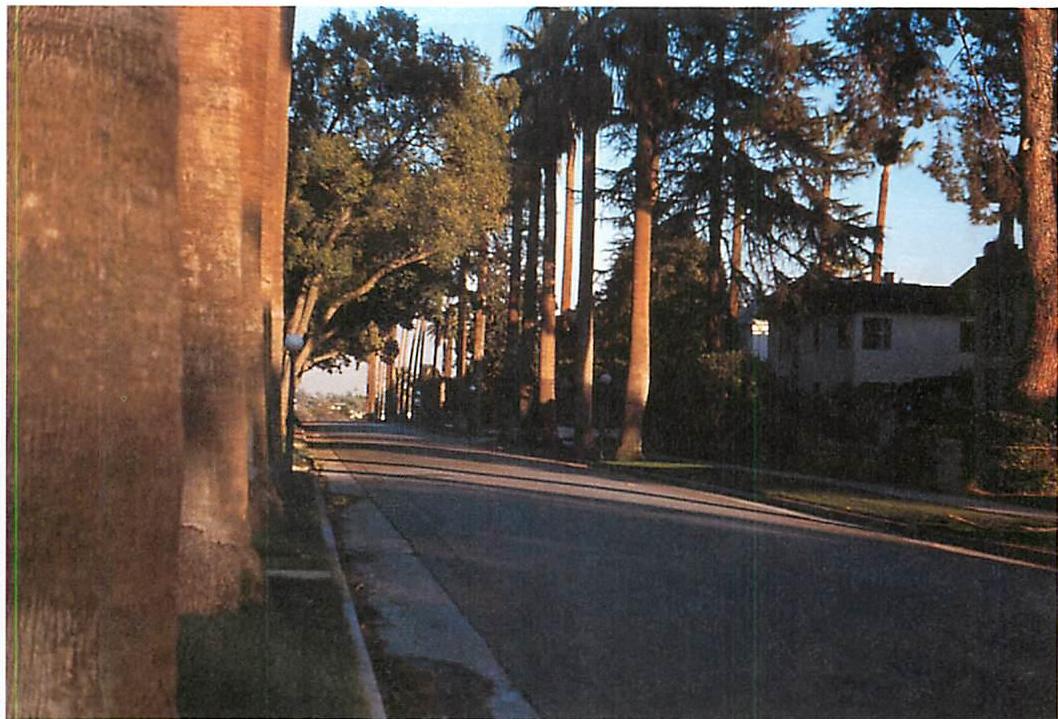

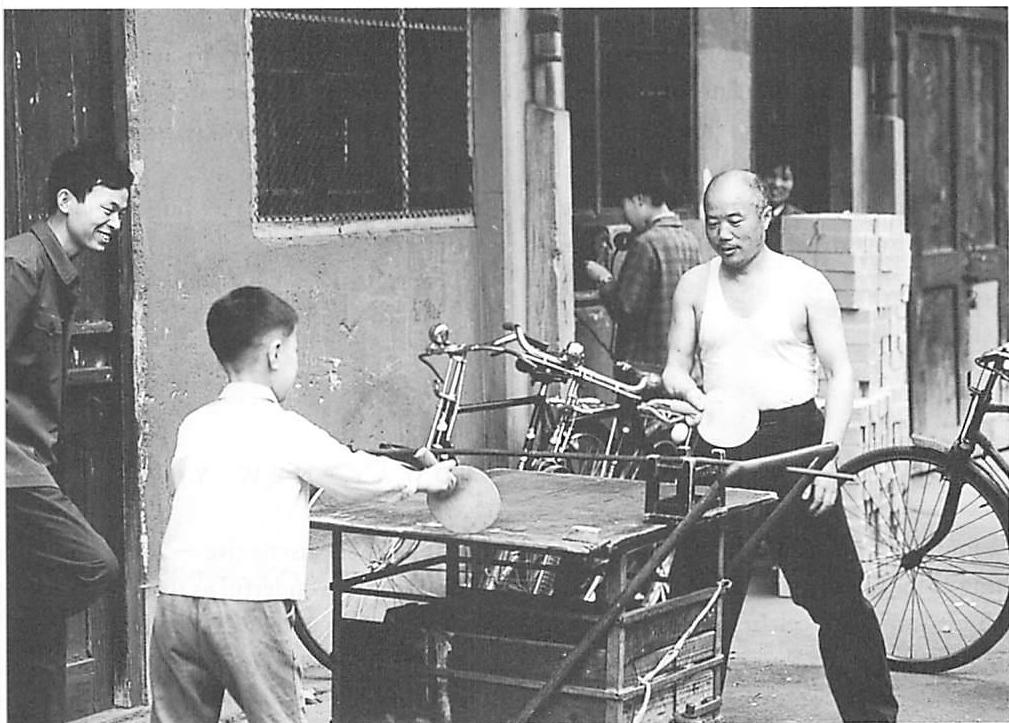

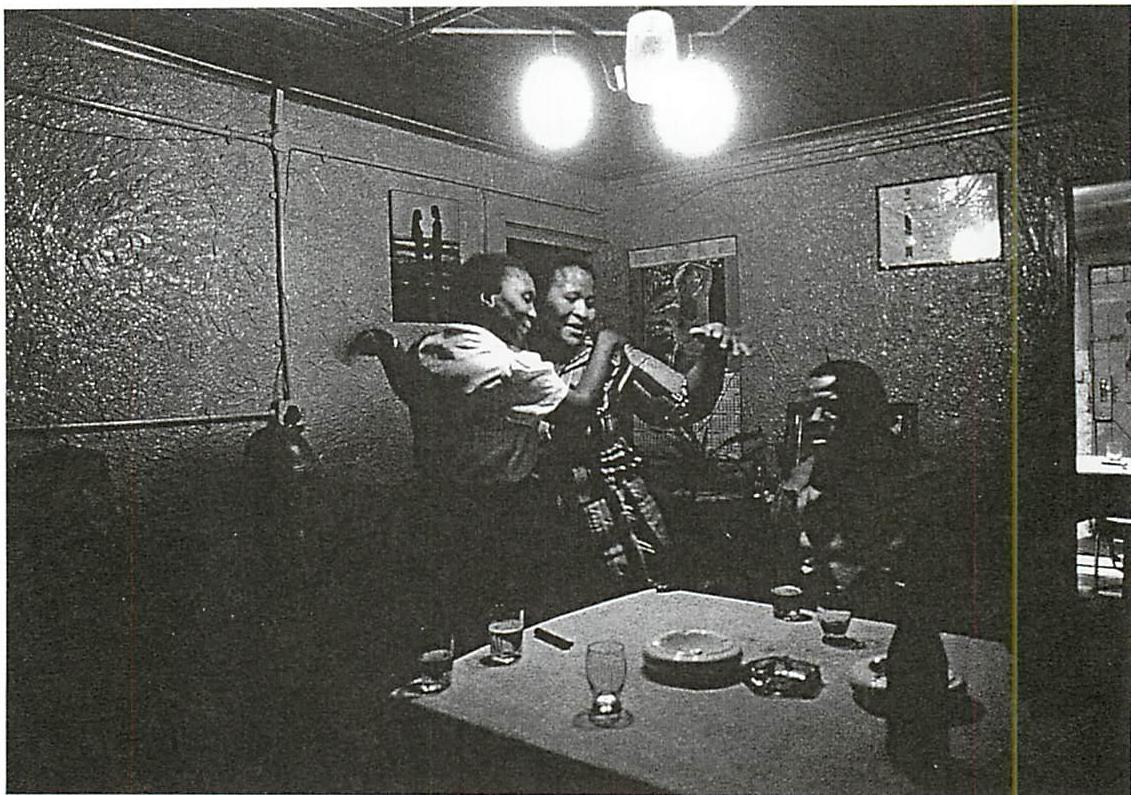

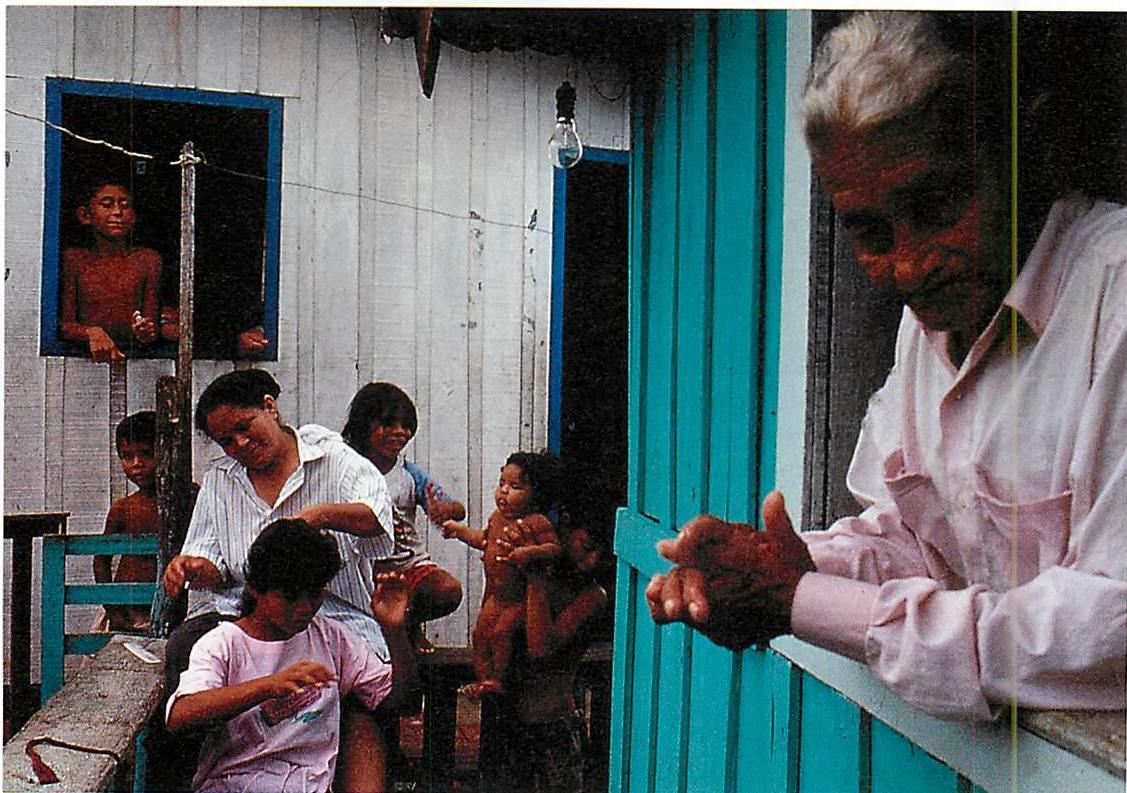

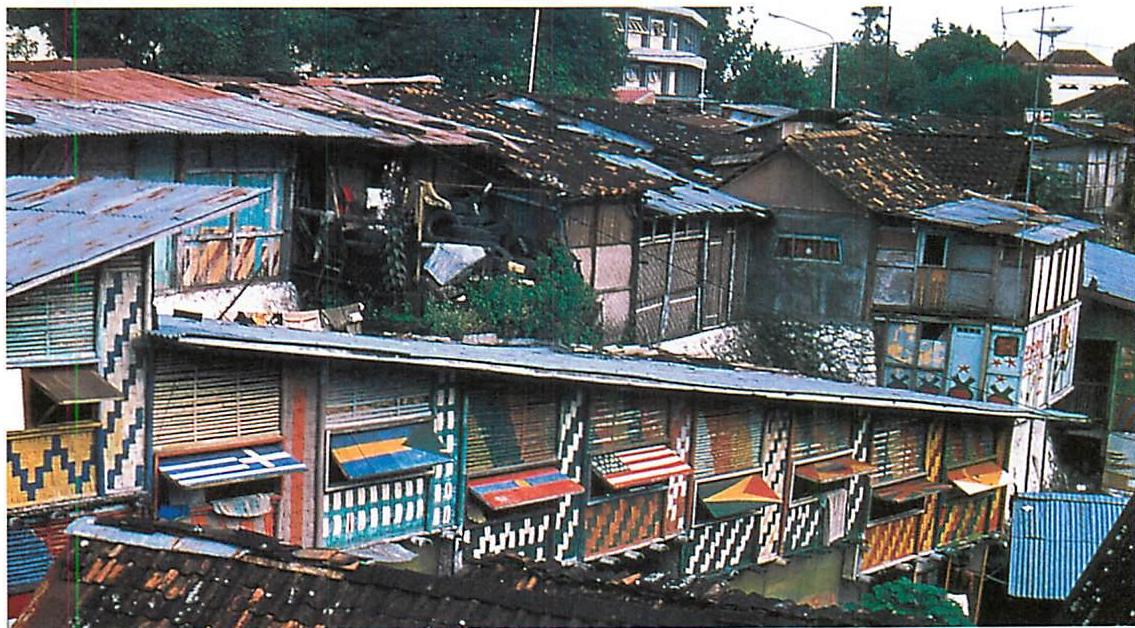

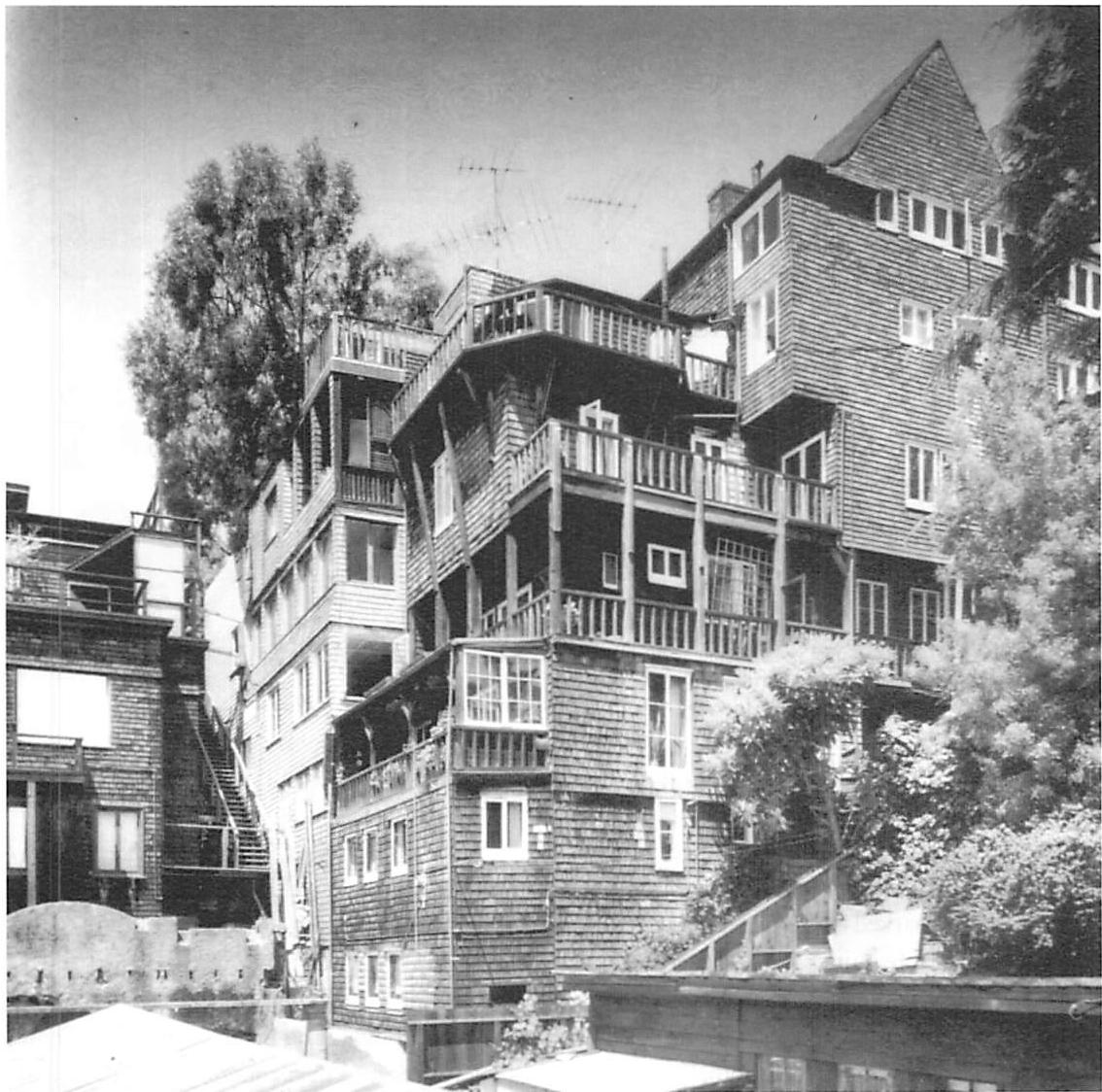

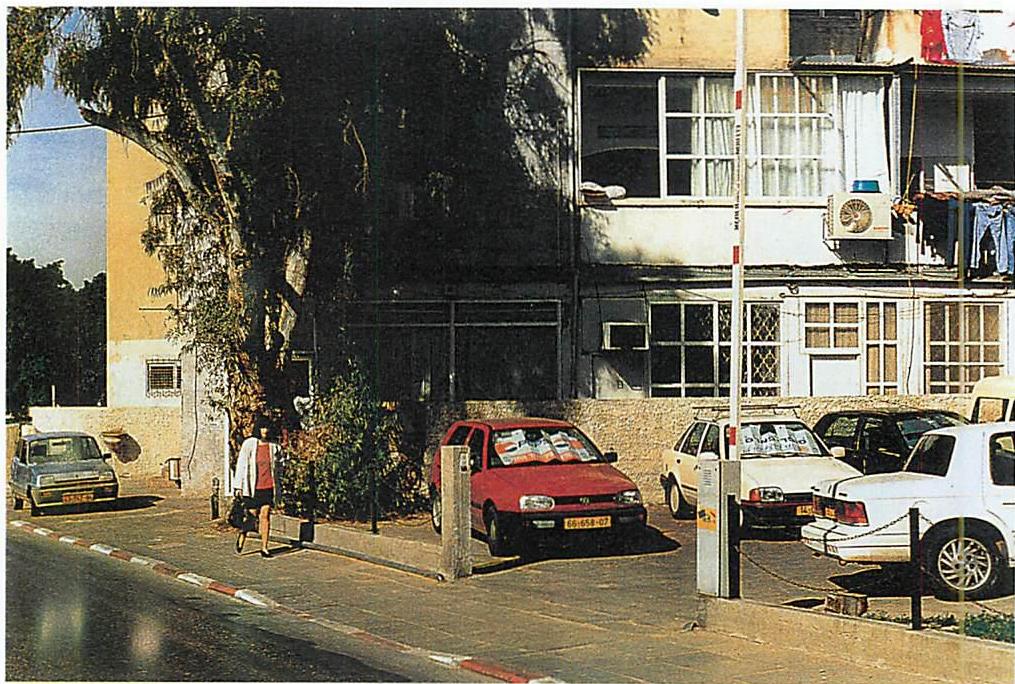

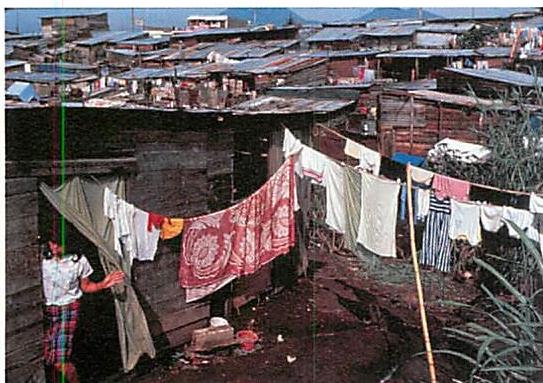

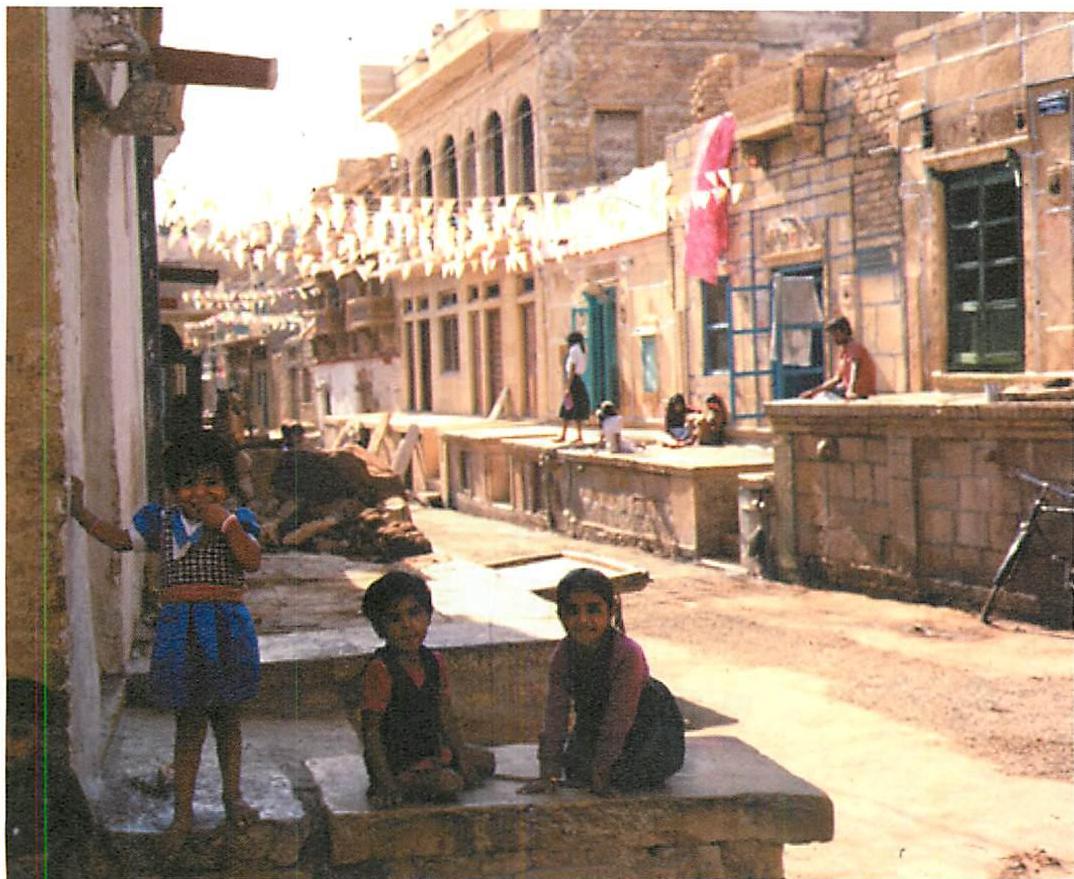

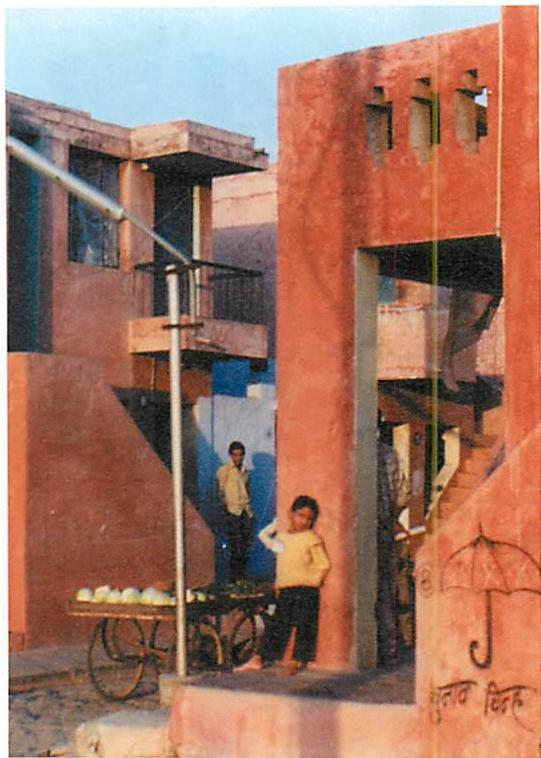

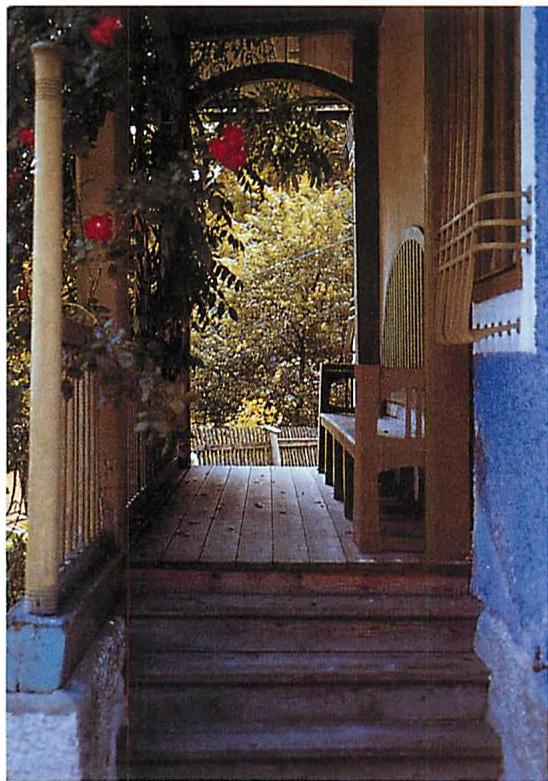

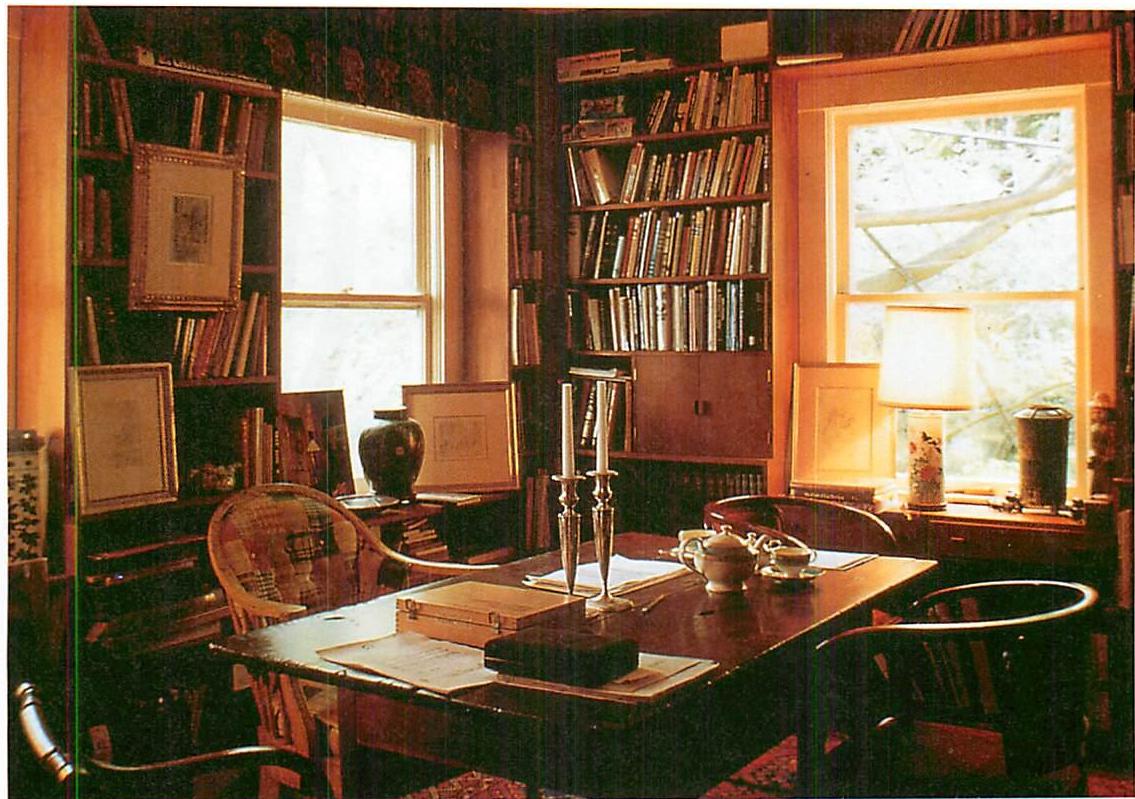

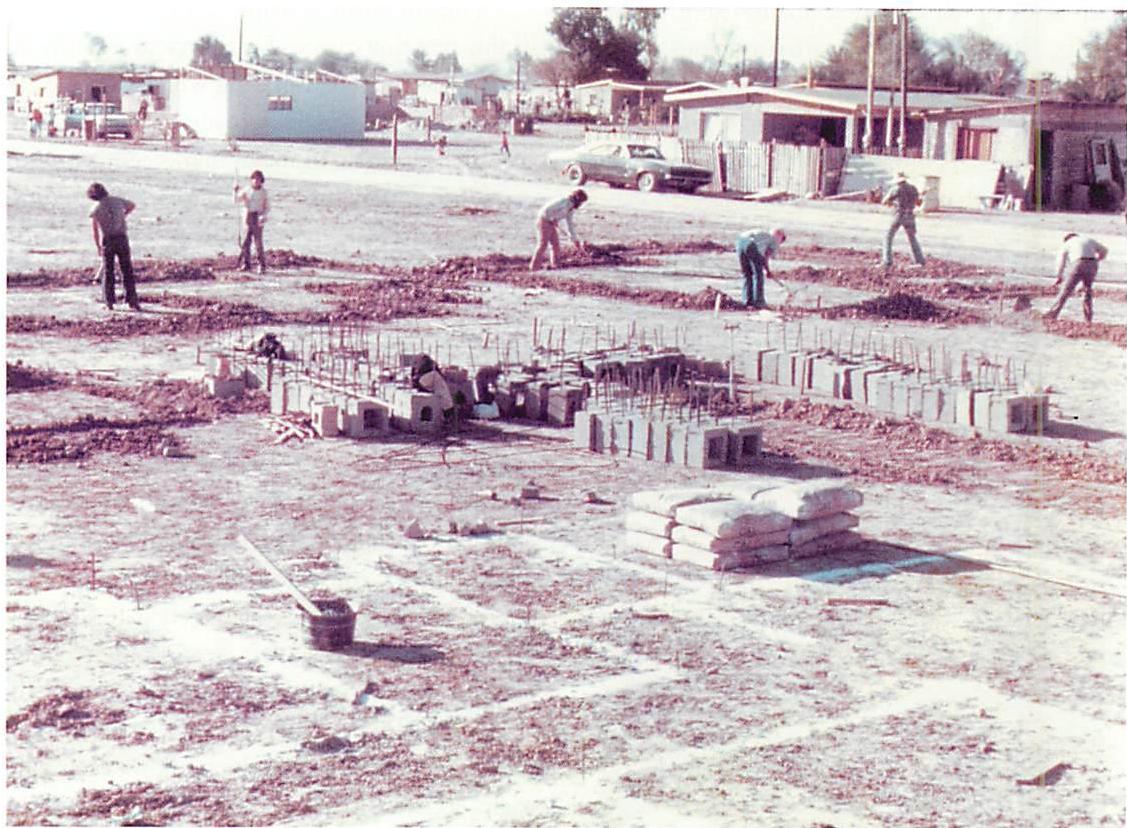

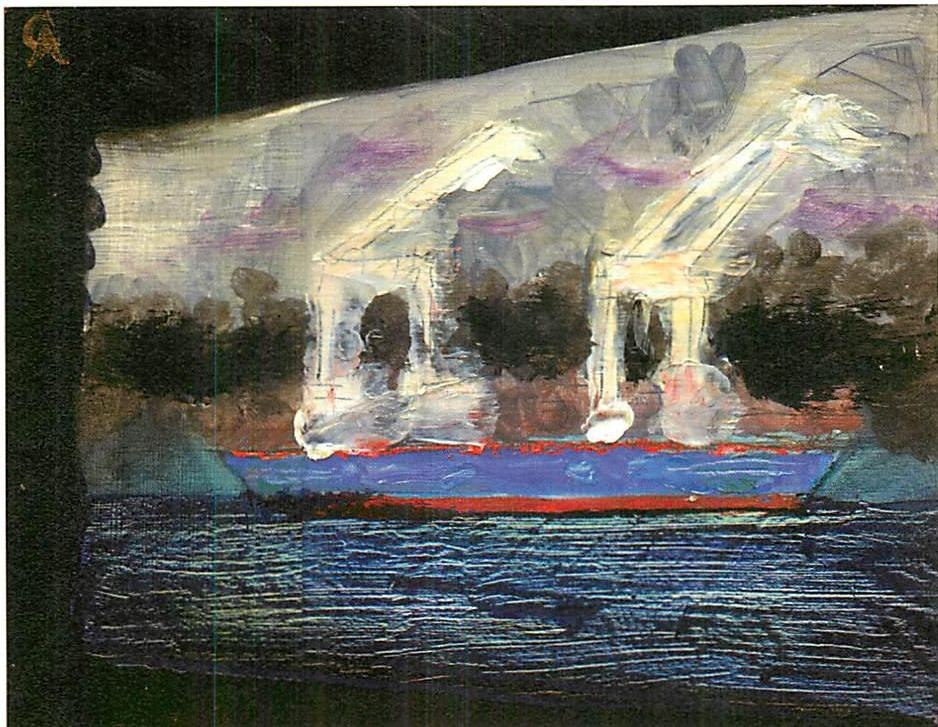

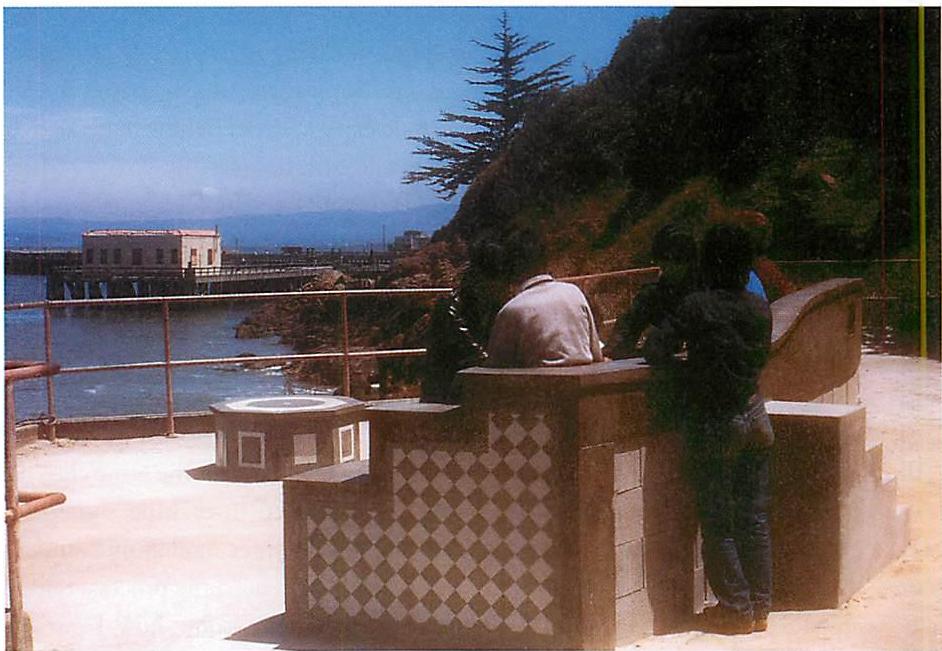

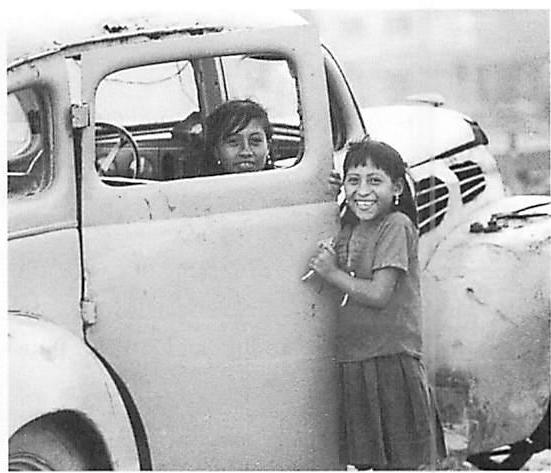

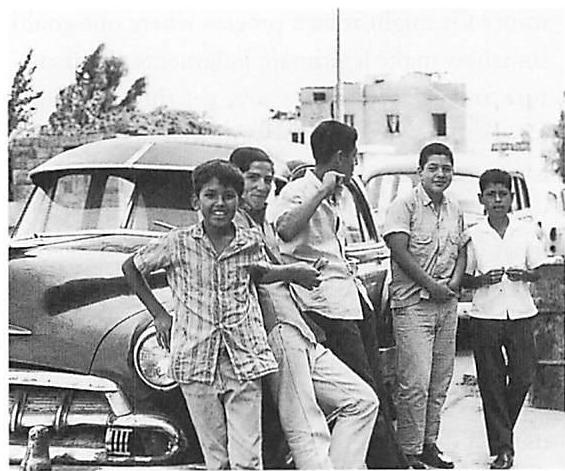

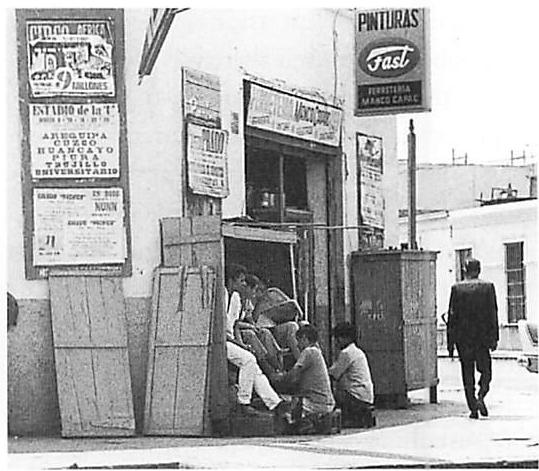

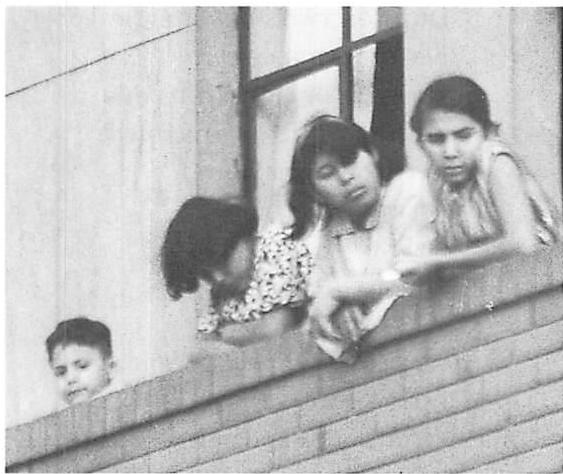

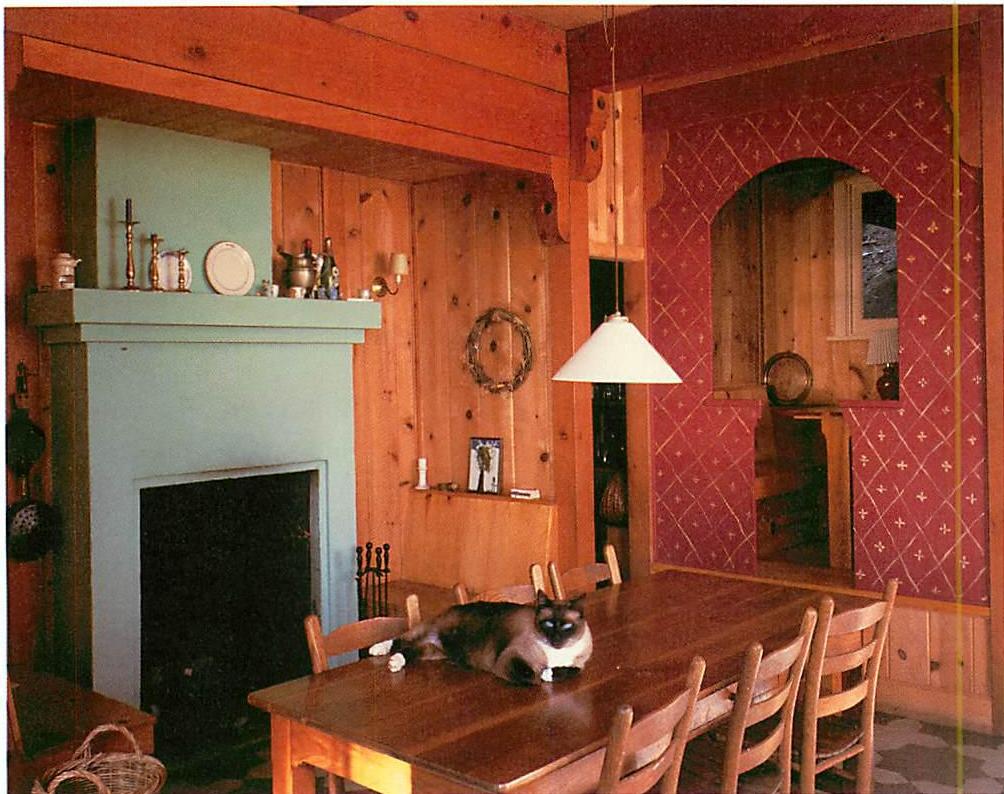

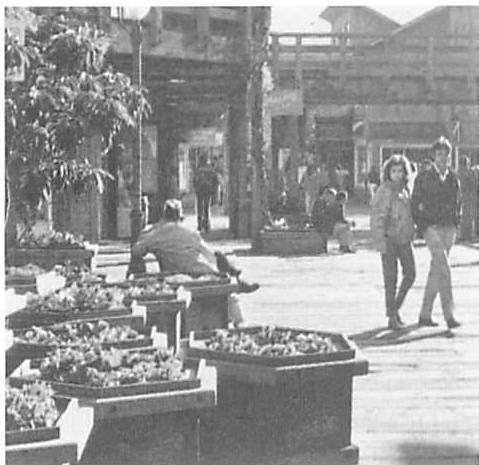

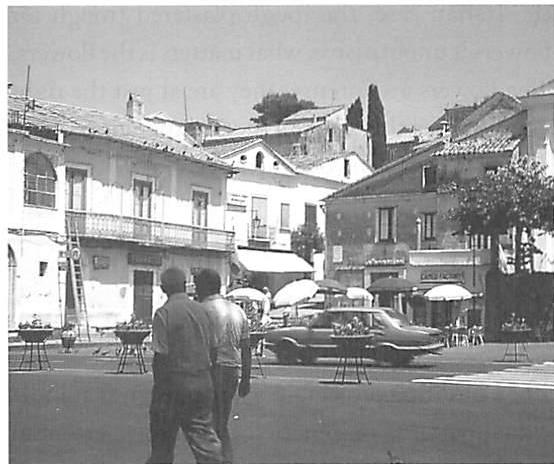

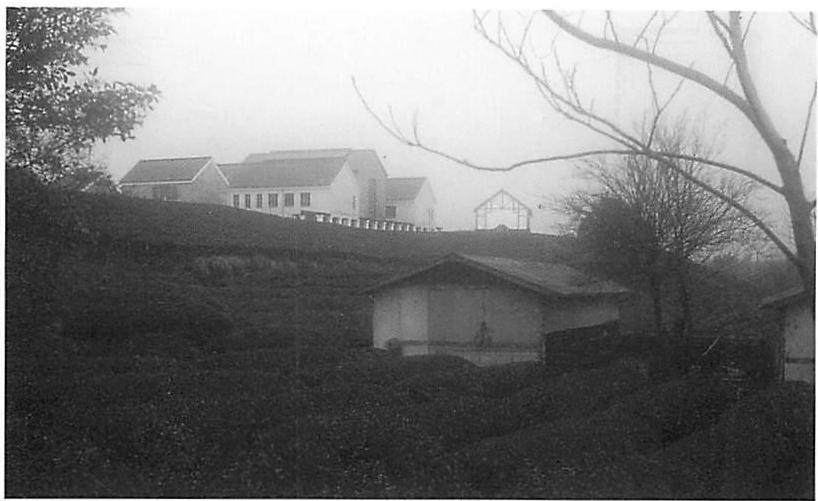

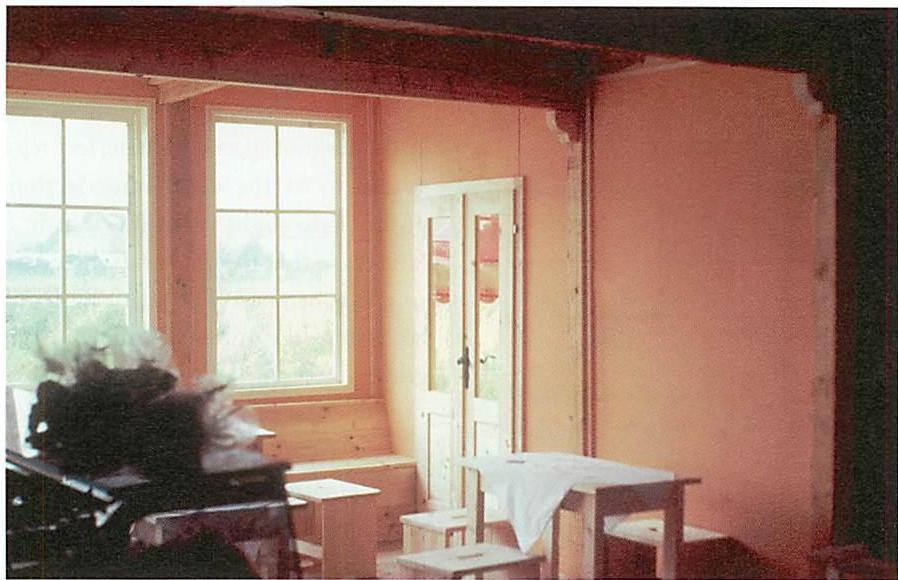

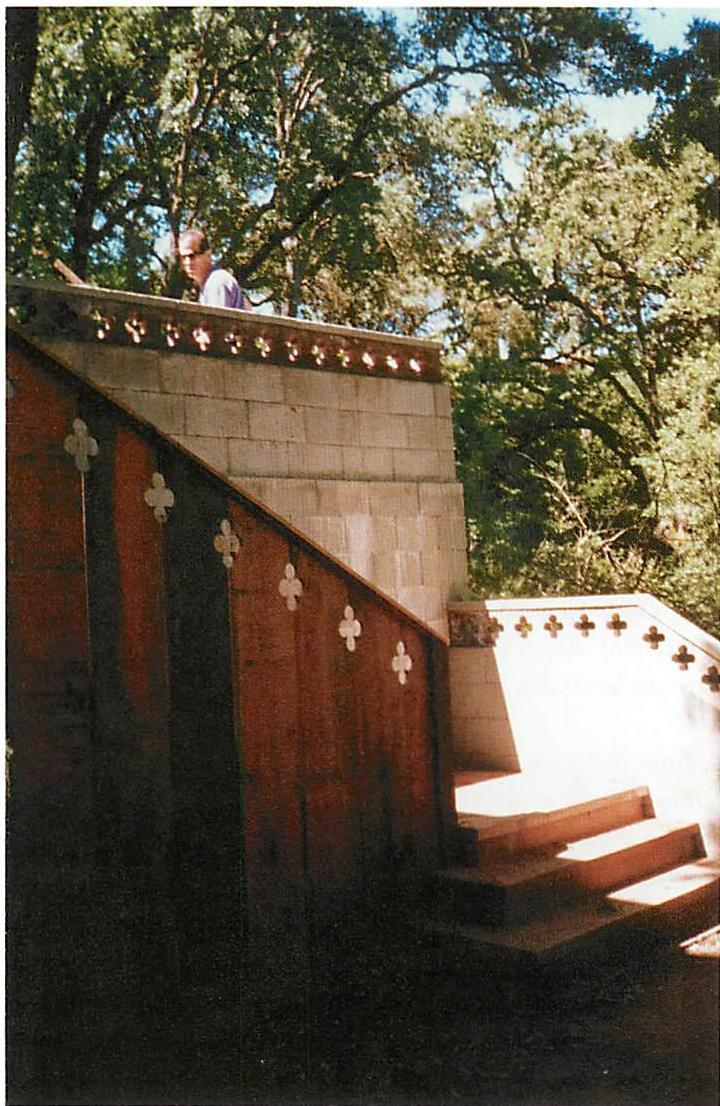

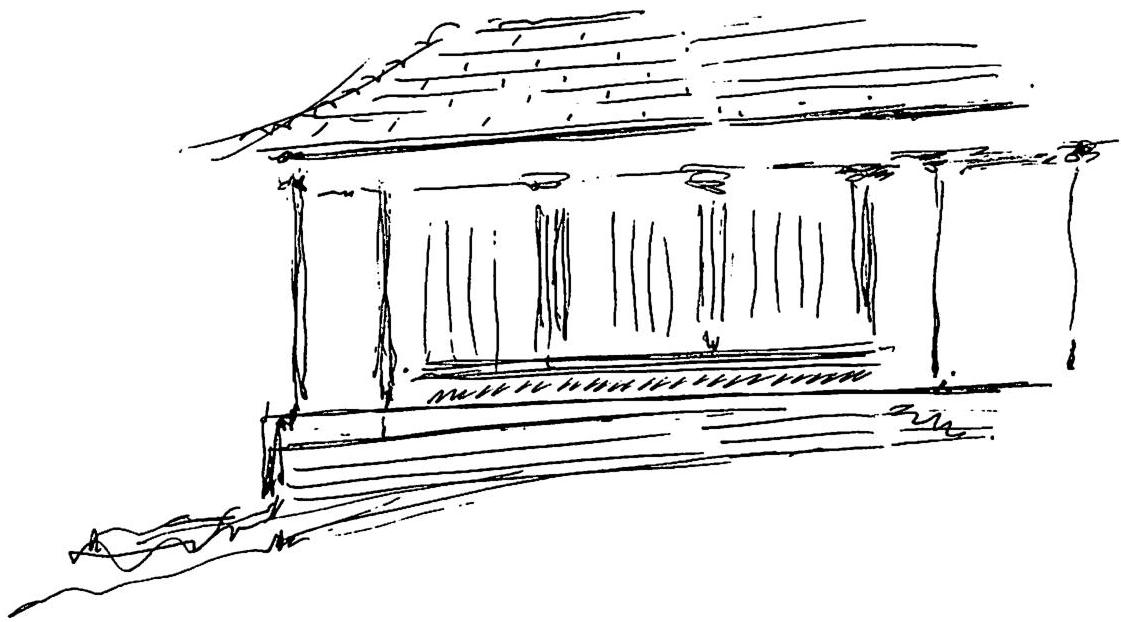

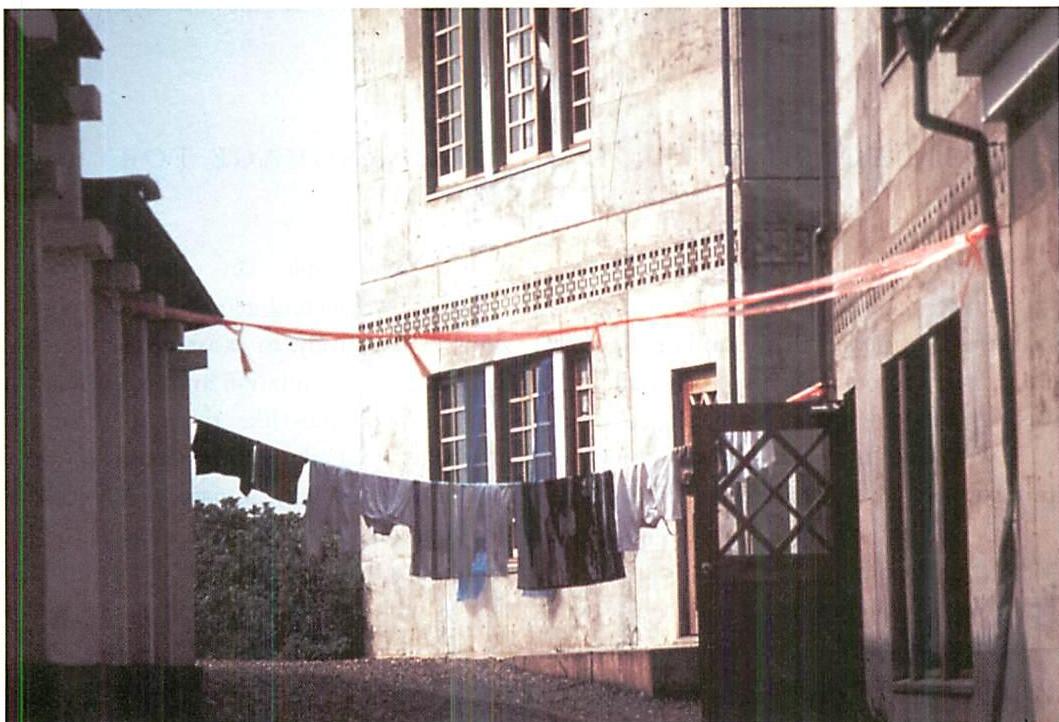

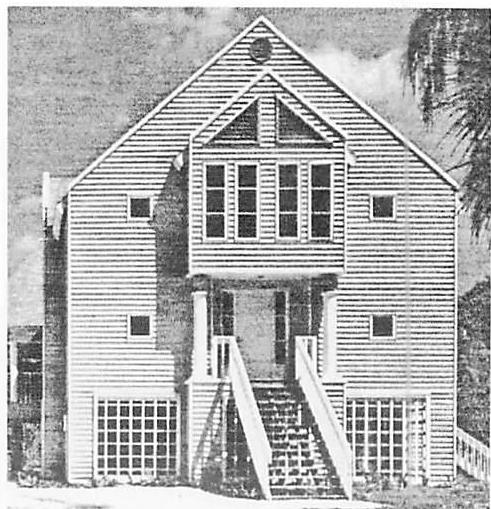

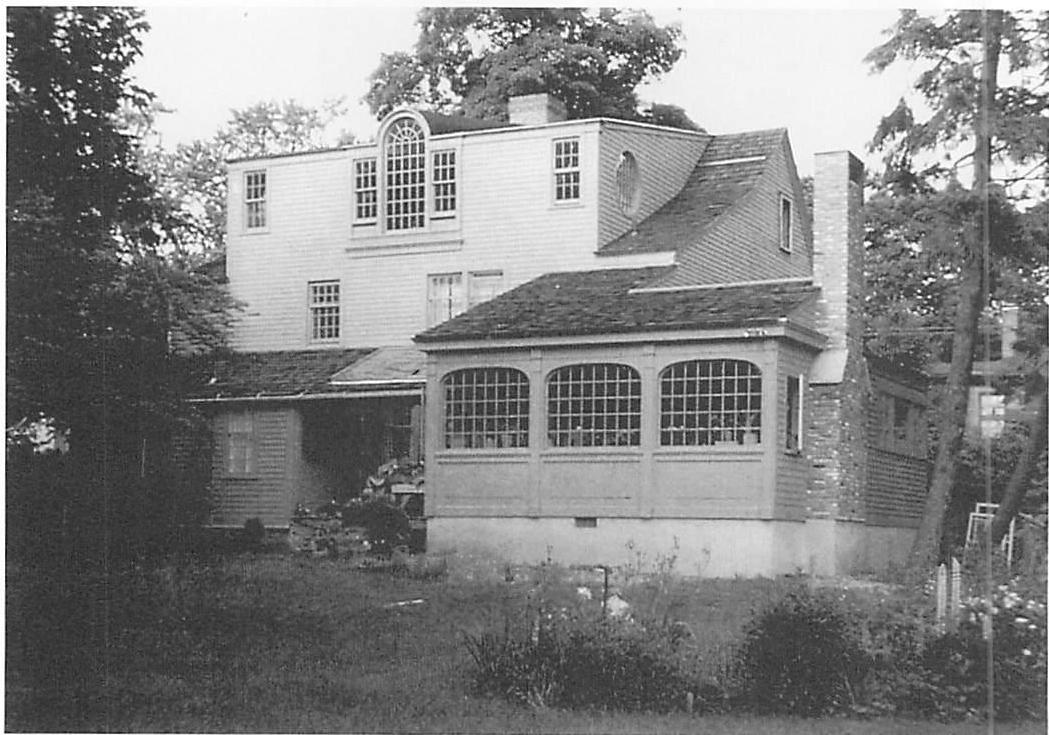

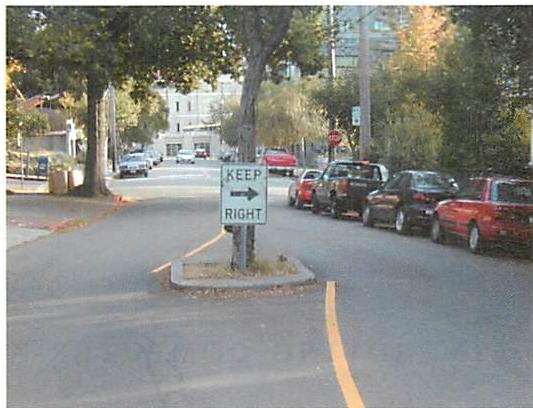

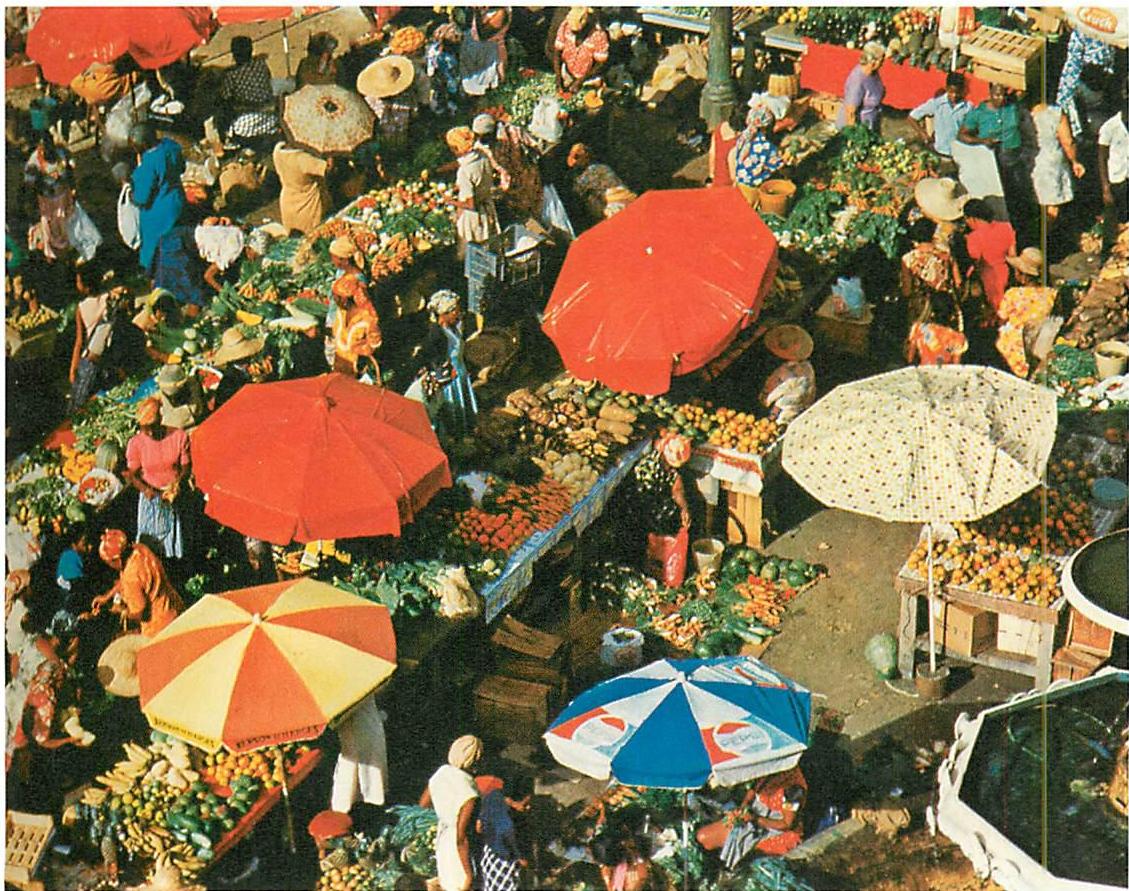

REAL LIFE CREATED BY A PROCESS IN THE CARIBBEAN

In the photograph opposite, we see a situation which would, normally, be classified as poverty. The houses are rudimentary, the road is roughly paved, two of the men are barefoot. Yet for all its poverty, which is certainly real, we can detect the residue of living process in this scene. The men are happy, evidently. They are talking and smiling and dreaming with quiet enjoyment. The road goes just where it is needed. It interferes little with the land, and leaves it harmonious. The houses, made of wood and corrugated iron, are placed in convenient spots, the right distance apart, making a lively spot between. The vegetation of the mountain is largely untouched. In this scene — both in its human happiness and in its architecture — we see a case of wonderful life. We see the impact of hundreds of acts, done by different people, making a living street where, rich or poor, people are truly comfortable. The ordinary old porch, steps, windows, and doors — how pleasant the way they sit with the street. One man sits happily, half on his side, comfortable, looking at his friend, and leaning on the ground. The trees, the columns, the deck chair, the tree branches have all happened step by step, with the

hardly conscious adaptation of each fence-post, path, seedling, each season of painting. Buildings and plants, even the people with them, have unfolded together, making something comfortable, ordinary, and profound.

It should be repeated again and again, and understood, that the capacity of a society to create living structure in its architecture is a dynamic capacity which depends on the nature and character of the processes used to create form, and to create the precise sequence and character of the unfoldings that occur during the daily creation of building form and landscape form and street form.

For this purpose I shall, in the chapters of this book, move from the technical language of structure-preserving process to the broader and more intuitive language of living process. I shall define a living process as any process that is capable of generating living structure. But, as we shall see in the book, the concept — and its implementation — require a wider and more everyday understanding of what is involved, an understanding which fits with the daily acceptance of day-to-day process and generic process — in

short, one that can be compatible with everyday individual and social process and with the institutionalized process of professions like architecture, and of the other social activities which play a major role in shaping the environment.

Above all, the living processes which I shall describe, are—as it turns out—enormously complex. The idea that all living processes are structure-preserving turns out to be merely the tip of a very large iceberg of hidden complexity. The subject of living process is a topic of great richness, which is likely to keep us occupied for centuries as we try to master its variety of meanings and its attributes and potentialities.

A SOURCE OF LIFE

All this will have direct meaning in the world around us. If carried out, it will change our conception of our own life, and of our world. Above all it will change the character of our results. What may appear superficially as an informal, relaxing, rambling roughness of the Caribbean photograph is actually a far deeper order than the norm. It is what we experience as life. That is where real stories are made; where human beings experience a measure of the freedom, and difficulty, and incongruity of being human. It is not hard to be at ease in such places. They invite us to be what we are, and they allow us to be what we are.

It must be recognized that—morphologically speaking—to generate such complexity is a different task from generating the lifeless hulks portrayed in chapter 4, which have been the aspirations of too many clients and developers and architects in the modern age. This real life is an entirely different matter. The means needed to create this real life, to create living structure in the true meaning of the word—that has an order of difficulty we architects have almost never contemplated yet. Indeed, the small example of the street in Guadeloupe gives only a tiny glimpse of the true nature of complexity.

PREFACE

ON PROCESS

1 / A DYNAMIC VIEW OF ORDER

In Book 1, I tried to rearrange our definition of architectural order in such a way that it forms a basis for a new view of living structure in buildings and landscapes, escaping from the mechanistic dilemma.¹

Book 1 invited us to see the world around us — buildings, plants, a painting, our own faces and hands — as field-like structures with centers arranged in a systematic fashion and interacting within the whole. When a structure is living we will feel the echo of our own aliveness in response to it.² Book 2 takes the necessary next step of investigating the process of how living structure creates itself over time. A child becomes an adult without ever losing uniqueness or completeness. An acorn transforms smoothly into an oak, although the start and endpoint are radically different. A good building or city will unfold according to the living processes that generate living structure. What I describe throughout Book 2 is a comparably new view of architectural process, with a focus on architectural processes that are capable of generating living structure. It is my hope that a world of architecture, more suitable for human life, will emerge from this new view of living process and of what process is.

Book 2 invites us to reconsider the role and importance of process and how it is living or not. It is about the fact that order cannot be understood sufficiently well in purely static terms because there is something essentially dynamic about order. Living structure can be attained in practice, and will become fully comprehensible and reachable, only from a dynamic understanding. Indeed the nature of order is interwoven in its fundamental character with the nature of the processes which create the order.

When we look at order dynamically, the concept of living structure itself undergoes some change. Book 1 focused on the idea of living structure, and the viewpoint was geometric, static. In Book 2, I start with a second concept, based on the idea of an unfolded structure. The point of view — even for the structure itself — is dynamic.

The two conceptions of structure turn out to be complementary. In the end we shall see that living structure and unfolded structure are equivalent. All living structure is unfolded and all unfolded structure is living. And I believe the concept of an unfolded structure is as important, and should play as essential a role in architecture, as the concept of living structure. Thus we shall end up with two equivalent views — one static, one dynamic — of the same idea.

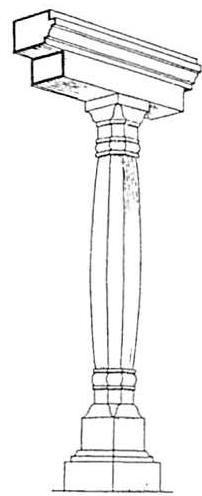

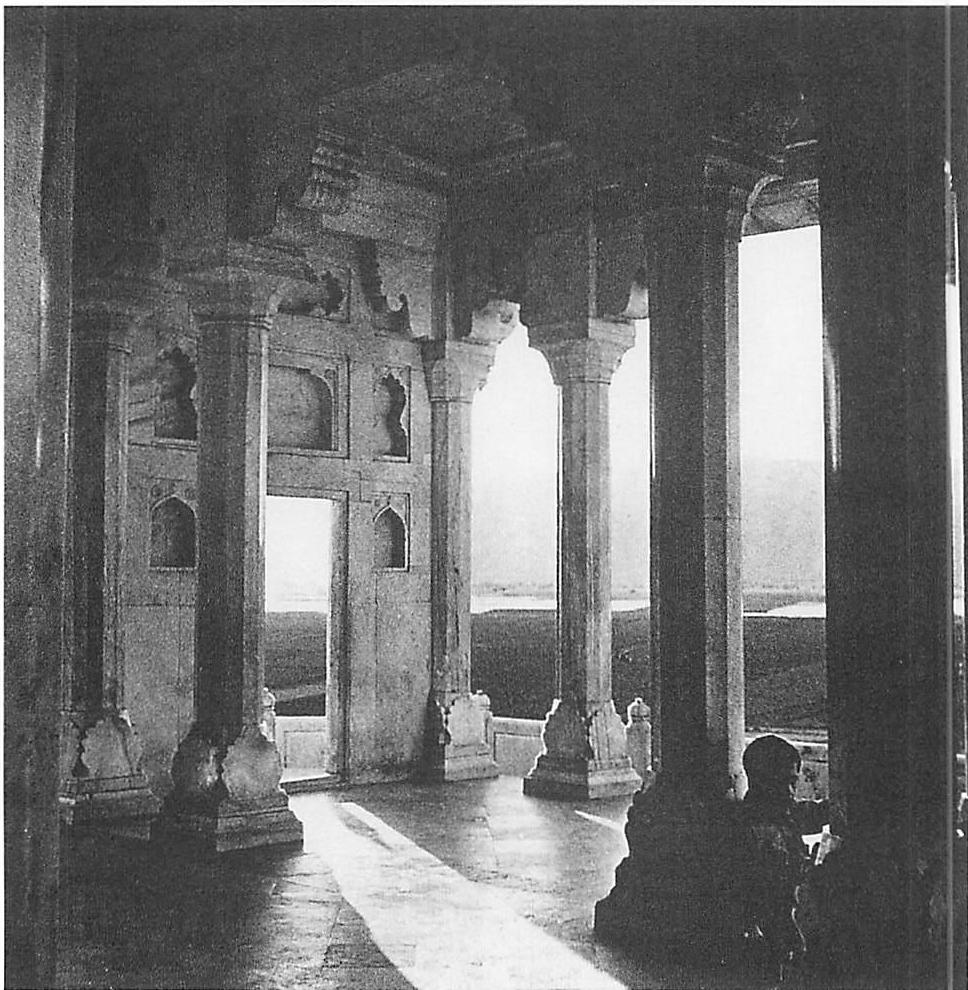

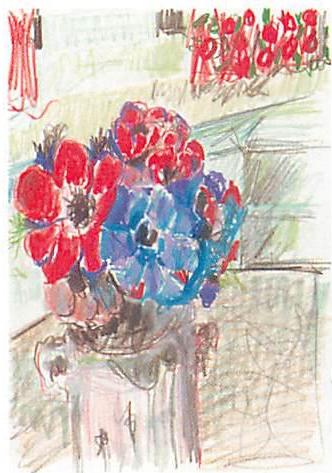

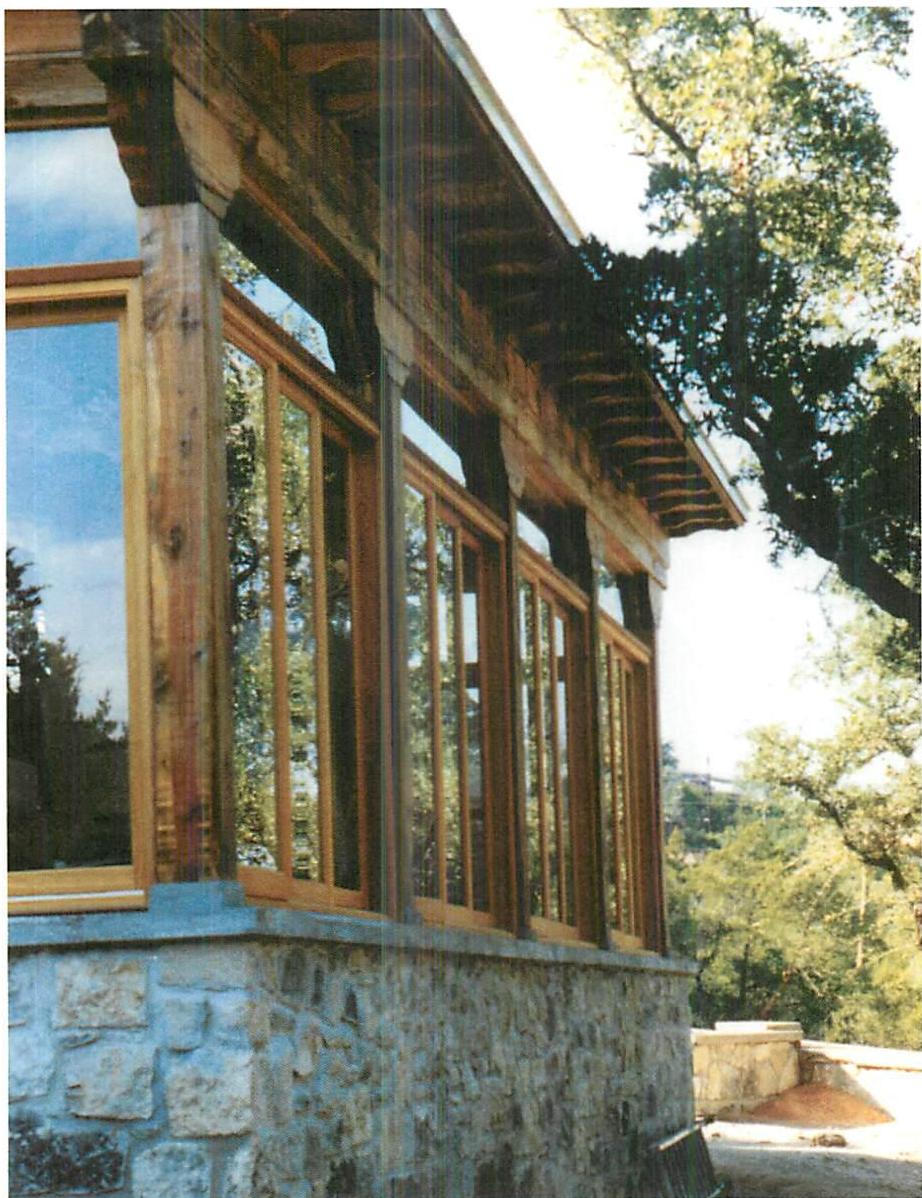

2 / THE NECESSARY ROLE OF PROCESS

The task of architecture may be simply stated. We seek to make a living architecture: that means an architecture in which every part, every building, every street, every garden, is alive. It has tens of thousands of living centers in it. It has rooms, gardens, windows, each with their own life. It has stairs, passages, entrances, terraces, columns, column capitals, arches. In a living environment, each of these individual places is a living center in its own right. The window is a glorious living center with light, comfort, view, and so on. The window sill is a living center, with shape, seat, a place for a vase of flowers. Even the smallest part of the most insignificant

room, a forgotten corner, has the quality of a living center. Even the smallest part of the physical structure, a brick, the mortar between two bricks, the joint of one piece of wood with another, also has this living character.³

What process can accomplish the subtle and beautiful adaptation of the parts that will create a living architecture? In a certain sense, the answer is simple. We have to make—or generate—the ten thousand living centers in the building, one by one. That is the core fact. And the ten thousand centers, to be living centers, must be beautifully adapted to one another within the whole: each must fit the others, each must contribute to the others, and the ten thousand centers then—if they are truly living—must form a coherent and harmonious whole.

It is generally assumed that doing all this well is the proper work of an architect. This is what an architect is supposed to do. It is what an architect is trained to do. And—in theory—it is what an architect knows how to do. There is a general belief that how it is done by the architect and others is part of the mystery of the art; one does not ask too many questions about it. Questions about how it is best done—by what process—are rarely raised. Yet in this book I shall argue that careful thought about the adaptation problem shows that it can only be done successfully, when following a certain very par

ticular kind of process. This does not mean that there is one ideal process which must be used. There are many thousands of different processes which can succeed. But to succeed, these processes must meet definite conditions—defined in the chapters which follow. Processes which meet these conditions, even though there may be thousands of them, are limited. They are rare and precious, compared with the millions upon millions of processes which are used daily for conceiving, designing, and building by architects and builders all over the world.

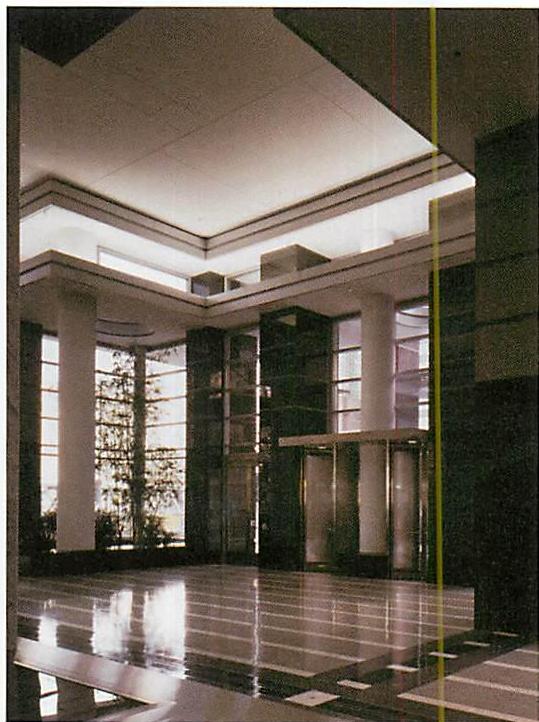

Many of the processes used today, sadly, are nearly bound to fail. We see the results of this failure all around us. The lifeless buildings and environments which have become common in modern society are not merely dead, non-living, structures. They are what they are precisely because of the social processes by which they have been conceived, designed, built, and paid for. No matter how skillful the architects, no matter how gifted, no matter how profound their powers of design—if the process used is wrong, the design cannot save the project.

Thus we shall see that processes (both of design and of construction) are more important, and larger in their effect on the quality of buildings, than the ability or training of the architect. Processes play a more fundamental role in determining the life or death of the building than does the "design."⁴

3 / ORDER AS BECOMING

In many sciences, it has become commonplace to consider process as an inescapable part of order. In physics, for example, forces themselves are now seen as processes, and the structure we observe in the world of atoms and electrons is known to come about as a result of the continuous play of subatomic processes defined by quantum mechanics.⁵ In biology, the structure of an organism is understood to be inseparable from

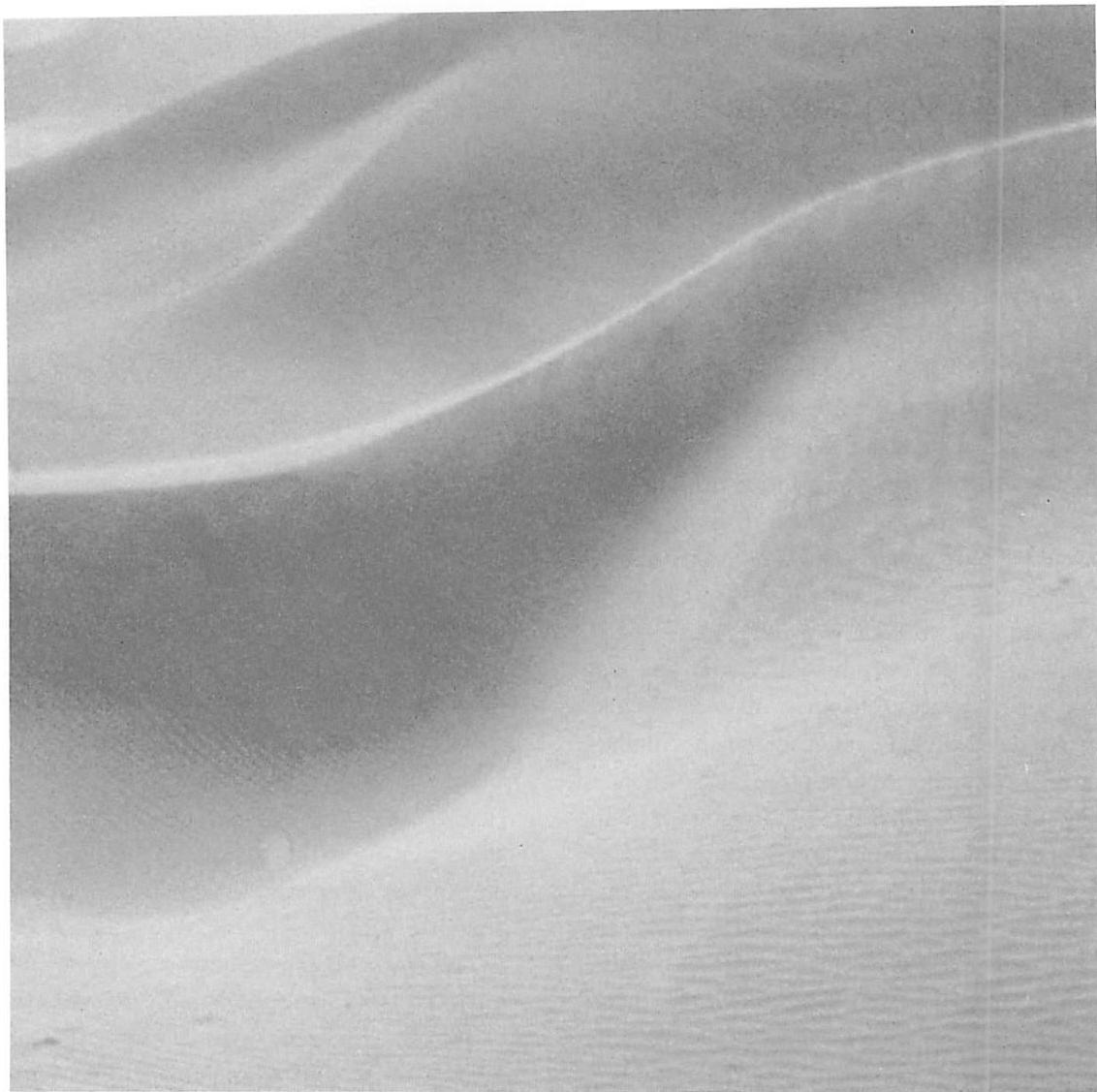

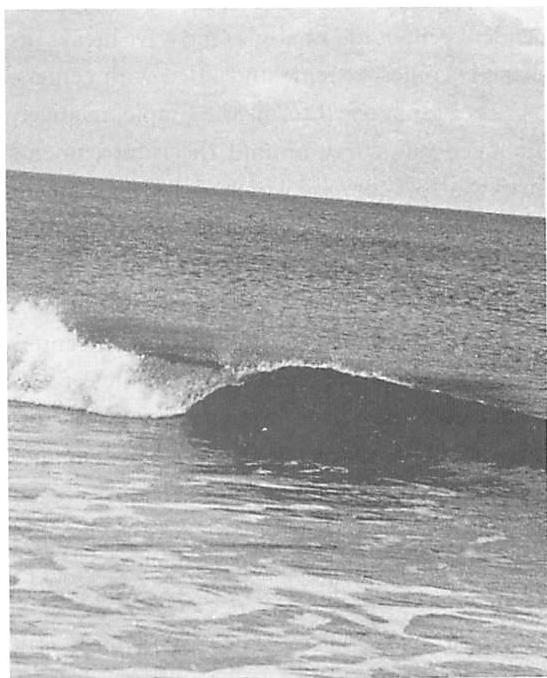

the process which creates and maintains it: an animal, at any instant, is the ongoing result of certain genetically controlled processes which create the organism to begin with, and which continue to create that organism throughout its life. A cloud is a transitory by-product of the condensation of water in the atmosphere. The waves of the ocean are the flowing product of the process of interaction between wind and water.

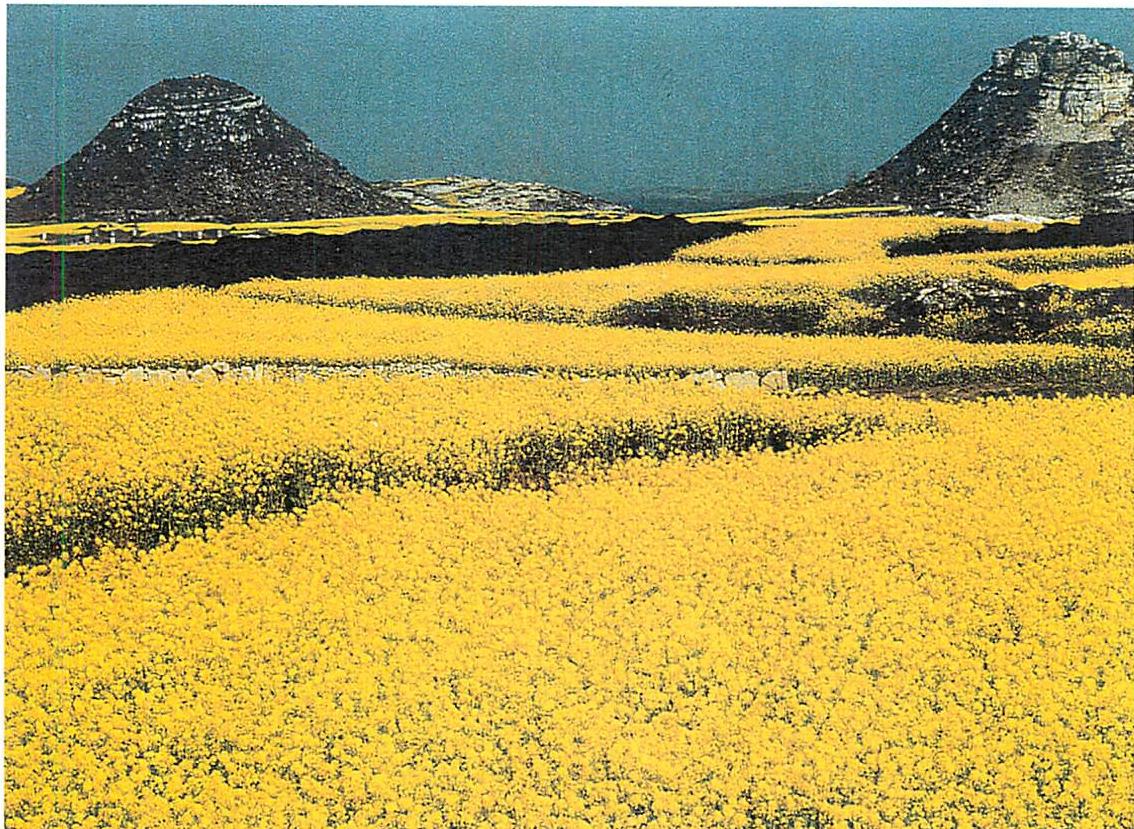

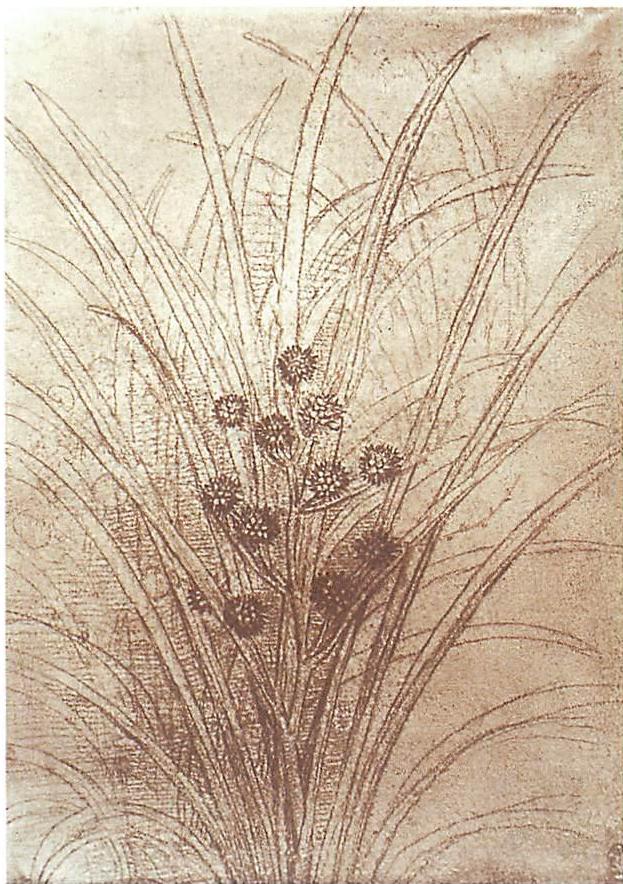

The sand ripples in the Sahara are the product of the process by which the wind takes sand, picks it up, and drops it. The mountain is the temporary product of the folding and heaving of the earth. The flower is the temporary product of the unfolding of the bud and seed pod under the driving influence of DNA. In each case, the whole system of order we observe is only an instantaneous cross section, in time, of a continuous and ongoing process of flux and change.

These insights originated 2,500 years ago with Heraclitus and his assertion that we can never step into the same river twice. But arriving at this understanding in modern science has been a difficult affair. D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, describing the origins of biological form in 1917 as a necessary result of biological growth, had to struggle intellectually, showing again and again by example that biological form could only be understood as a product of the growth process.⁶

Much more recently, the physicist Ilya Prigogine took decades, and many books and papers, to show that physics must be understood as a directional process — and that the way classical physics viewed phenomena without the orientation of time was fundamentally at odds with reality and was incapable, therefore, of describing some of the most important physical phenomena. As Prigogine wrote in 1980: "in classical physics change is nothing but a denial of becoming and time is only a parameter, unaffected by the transformation that it describes."

Now, at the turn into the 21st century, the "process" insight has finally arrived in most scientific disciplines. Gradually, a modern view has come into focus where we understand that it is the transformations from moment to moment which govern order in a system.

However, despite the great progress made in many sciences and humanities, the concept of process has not yet become a normal part of the way we think about architecture. The words Prigogine used in 1980, criticizing mainstream 20th-century physics, could still be applied equally to contemporary mainstream architecture. Our current view of architecture rests on too little awareness of becoming as the most essential feature of the building process. Architects are much too concerned with the design of the world (its static structure), and not yet concerned enough with the design of the generative processes that create the world (its dynamic structure).

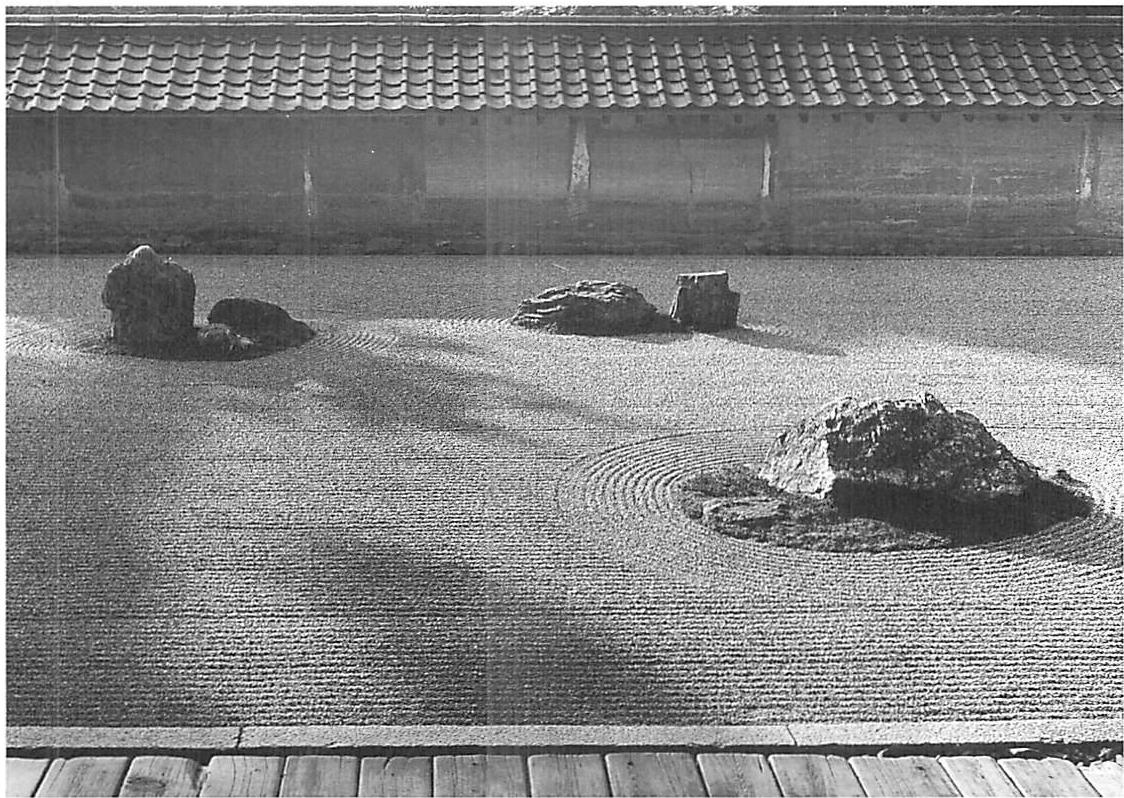

4 / PROCESS, THE KEY TO MAKING LIFE IN THINGS

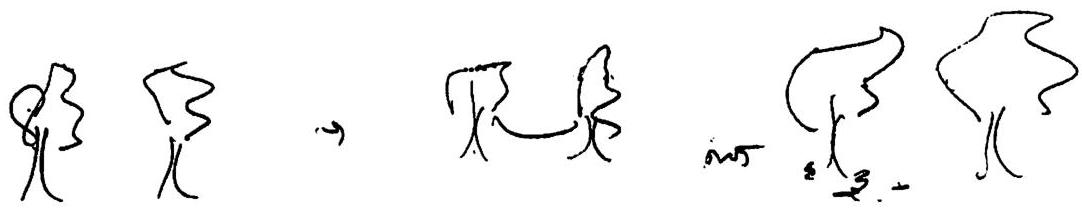

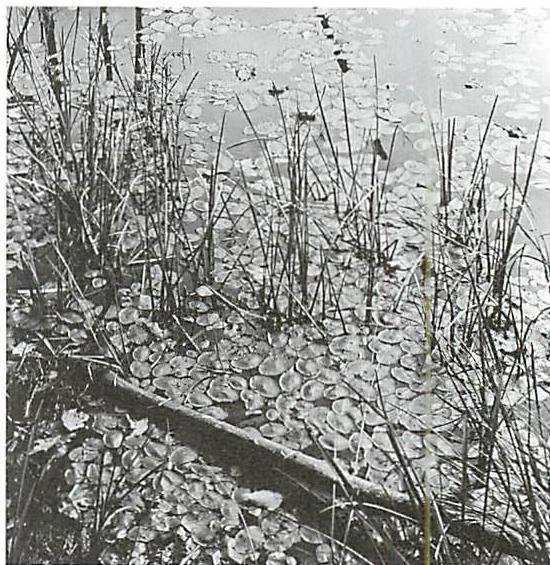

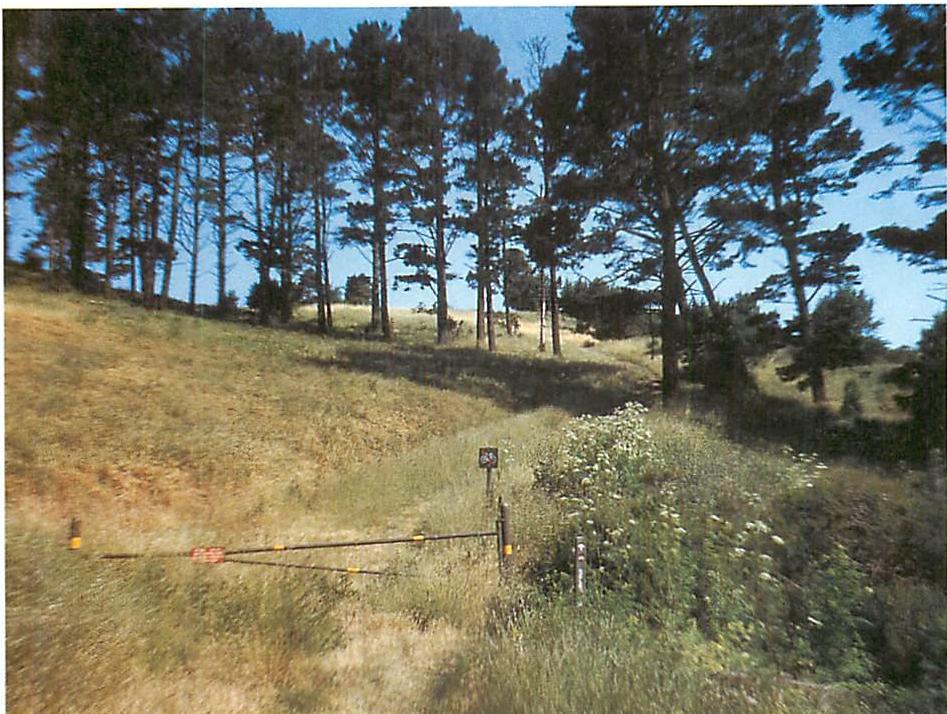

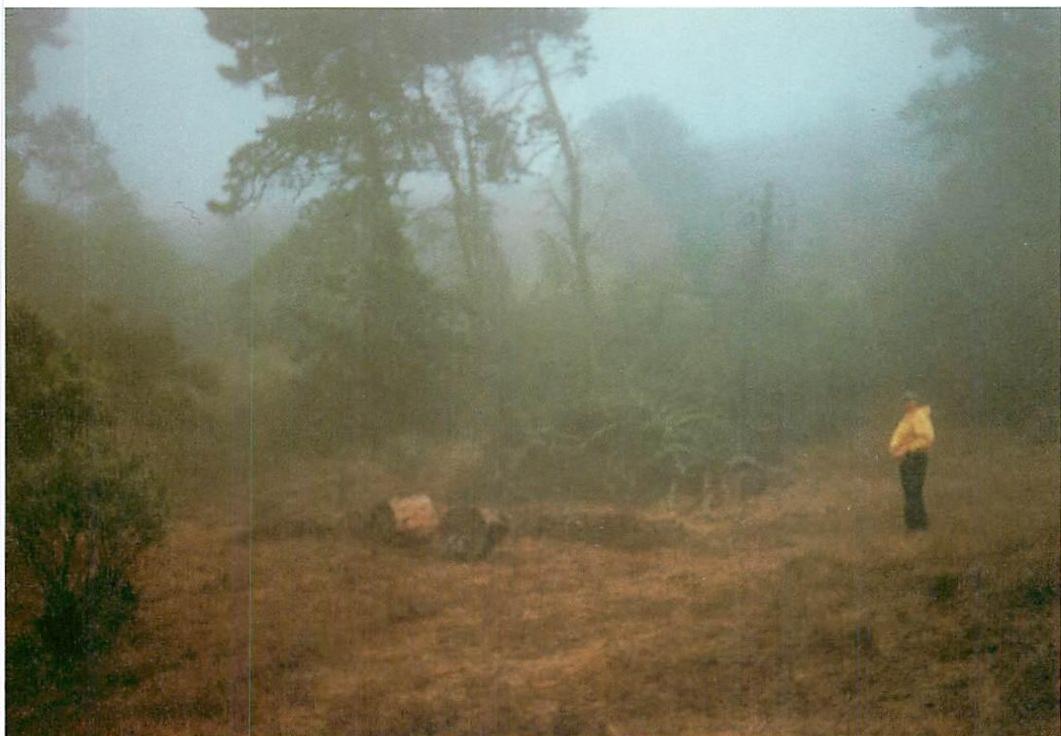

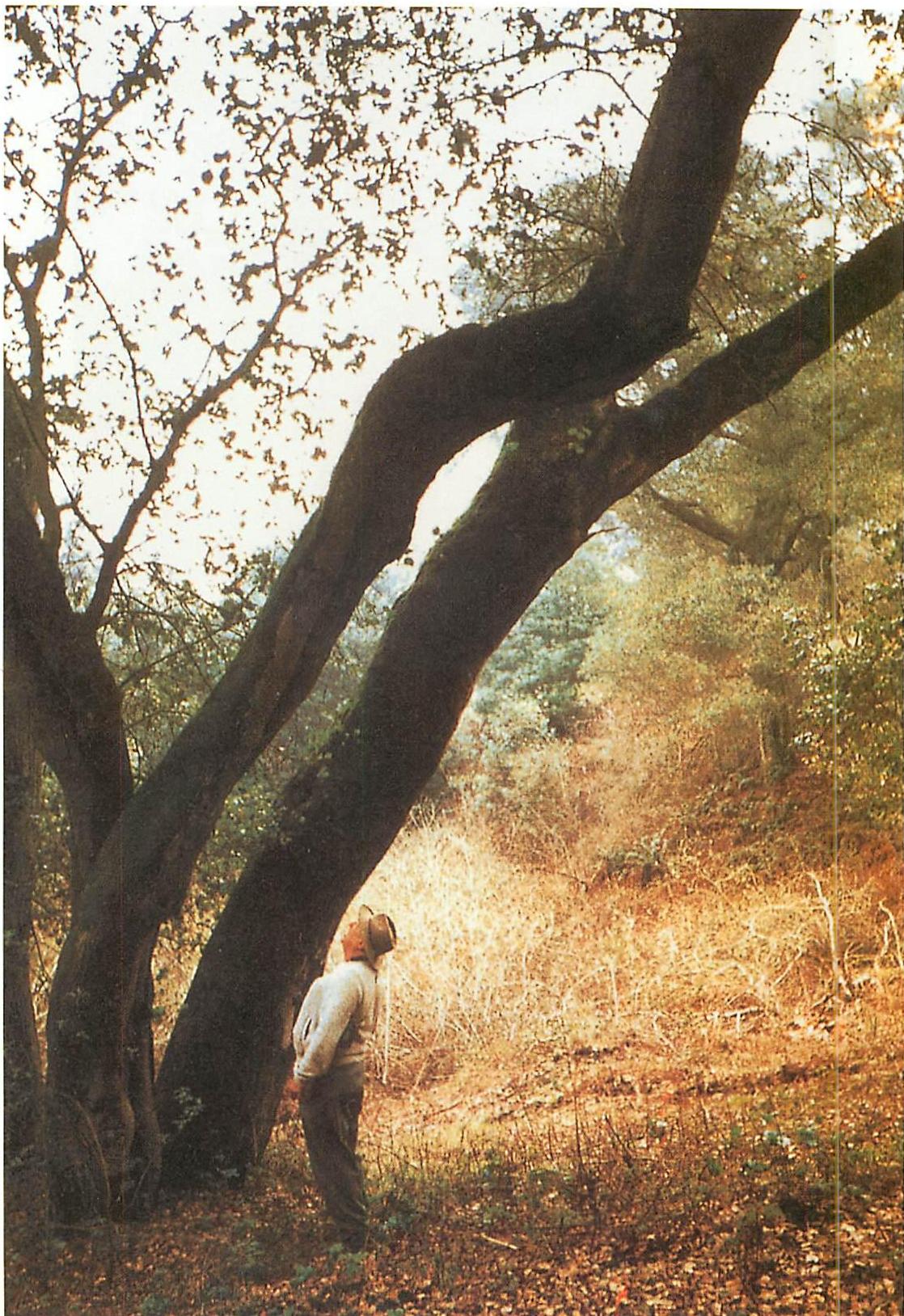

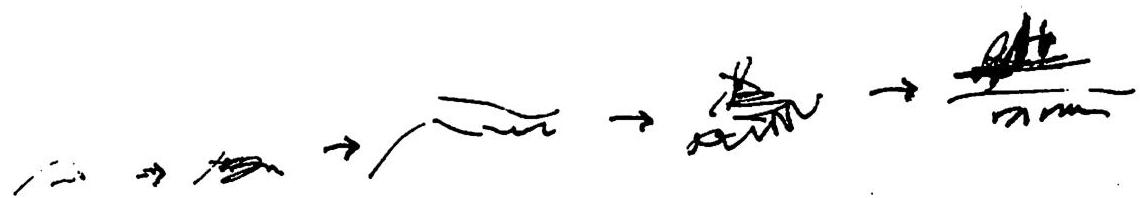

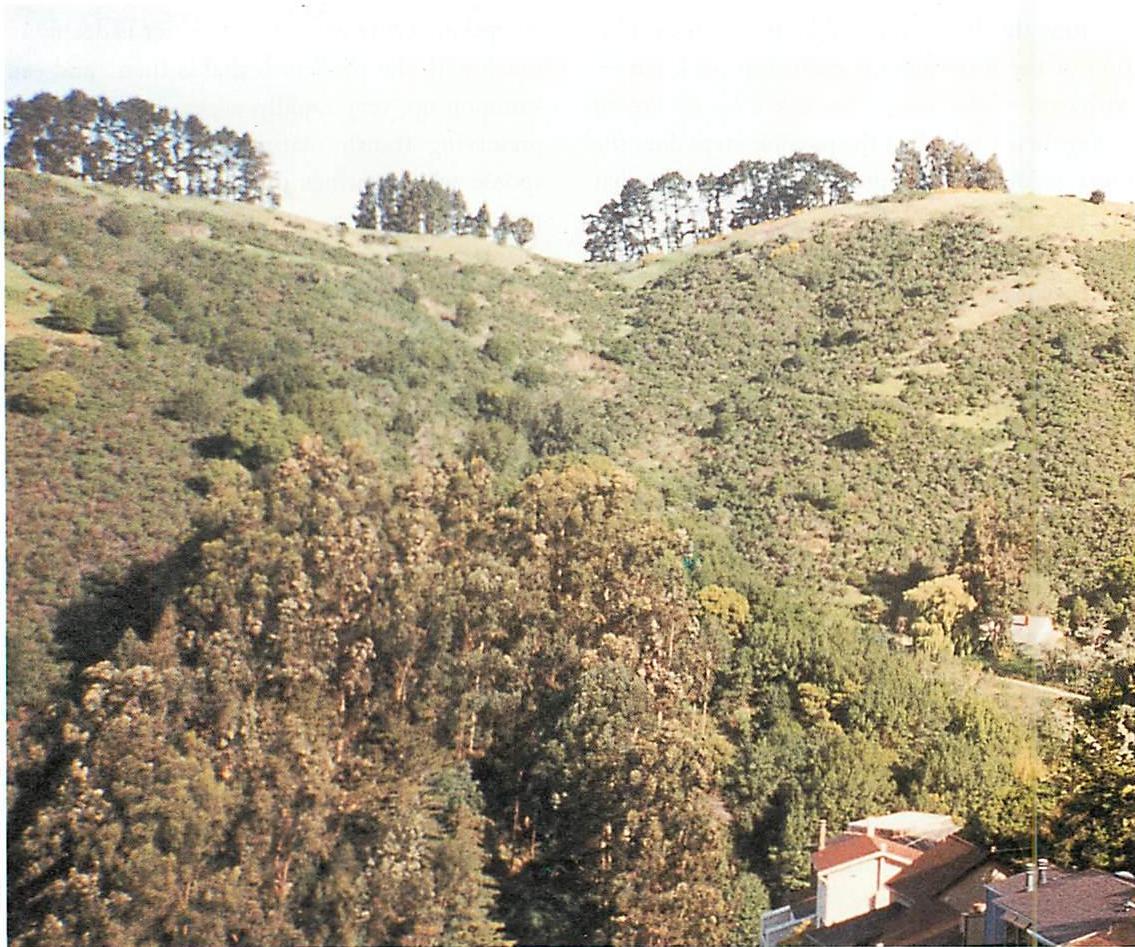

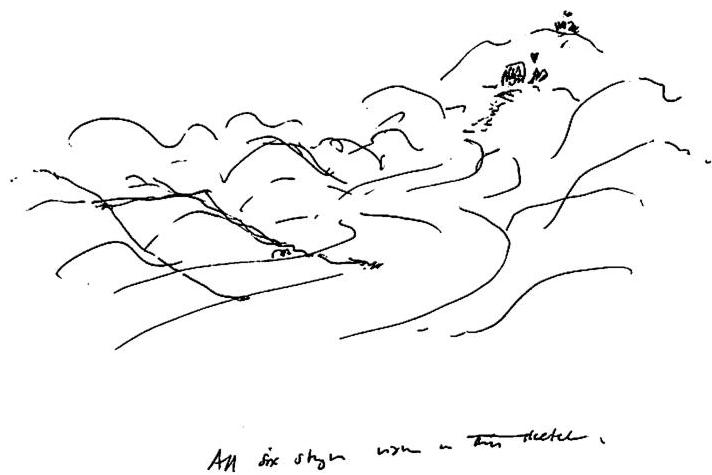

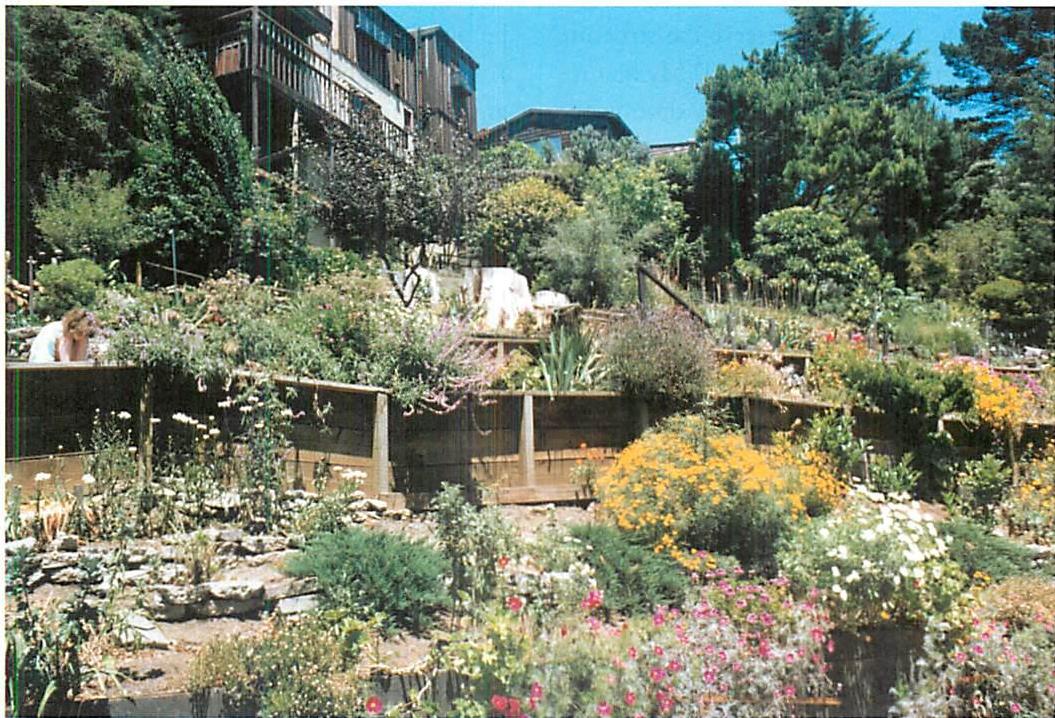

I think of my friend Bill McClung making his meadows in the hills of Berkeley.⁷ The near-wasteland of brush and eucalyptus, an overgrown and damaged landscape on the fringes of Berkeley becomes under his hand, something beautiful, alive.

Day after day, he goes up, gathers wood. He cuts poison oak and brush and thorn. He mows grassland, takes out bushes which have overgrown, takes out a tree which prevents another tree from having the light, from having its magnificence. He makes a pathway where I can walk, where he can walk.

Gradually, by cutting and removing, with a careful eye, he forms meadow: patches of grassland where the light falls, bounded by trees, looking toward a landscape, looking out toward the bay.

From something nearly destroyed, beautiful patches of land are formed. He clears the land of that scrub which makes the land too vulnerable to fire. He opens it, concentrates its beauty. Under the hand of this embellishment, each part becomes better; its uniqueness is preserved; its character intensified.

When he is done, each meadow has a different character. Each is ordinary, but a jewel,

an individual jewel. The fabric of the jewel-like living meadows all together, if he succeeds, will cover the ridge of the Berkeley hills.

When I ask him what makes him keep doing it, he answers, “The knowledge that I am making life: that something living is being enhanced. That keeps us inspired. It makes it worthwhile. It is a tremendous thing.”

But then I ask him, pushing, “Isn’t it really more the actual pleasure of each day? You go, and go again, because each day, each hour, is satisfying. It is simple work. You enjoy the sunshine, the open air, the physical sweat of carrying, and cutting. The smell of the grass as it opens up, the dog running in the grass, the comments of the neighbors.” And there is also the feeling of community, as people living near this bit of park begin to recognize Bill as a fixture, hope that he will keep on coming back; they appreciate what he does. His act makes him part of a community. And most of all, it is just pleasant, worth living for. The hours and minutes spent are rewarding in themselves.

I ask him if this pleasure in the process he is following is not worth almost more than the

knowledge that he is making something come to life? He acknowledges my comment and admits, “Yes, this daily ordinary thing is almost more important than the other.”

But it is the two together: the daily pleasure, breathing in the smell of the newly cut grass, with the deeper knowledge that goes with it that in this process he is making a living structure, up there on the ridge of the Berkeley hills.

On the other hand, processes which work against the existing life of a place, which fragment it, ignore it, cut across it, do damage. Even when they only ignore the wholeness or defy it with the best intentions, damage is done, disorder begins to occur. And as we watch the progress of the world, its growth, its change, we find that various acts — coming either from outside or from inside the thing itself — may be helpful or unhelpful to this wholeness which exists. This happens because the wholeness of any given thing may be helped or hindered by the character of the parts which it contains.

Once we recognize the possibility that some centers will be helpful to the life of an existing wholeness, while others will be antagonistic to

it, we then begin to recognize the possibility of a highly complex kind of self-consistency in any given wholeness. The various centers within a wholeness may be in harmony with one another in different degrees, or at odds with one another in different degrees. And this is where the degree of life, or degree of value, in any given thing comes from.

Thus we see that each given wholeness has a certain history: the wholeness becomes more valuable if the history allows this wholeness to unfold in a way that is considerate, respectful, of the existing structure, and less valuable if the steps which are taken in the emergence of the wholeness are antagonistic to the existing structure.

What is fascinating, then, is the hint of a conception of value which emerges dynamically from respect for existing structure. We do not need any arbitrary or external criterion of value. The value exists within the unfolding of the wholeness itself. When the wholeness unfolds unnaturally, value is destroyed. When the wholeness unfolds naturally, value is created.

That is the origin of living structure.

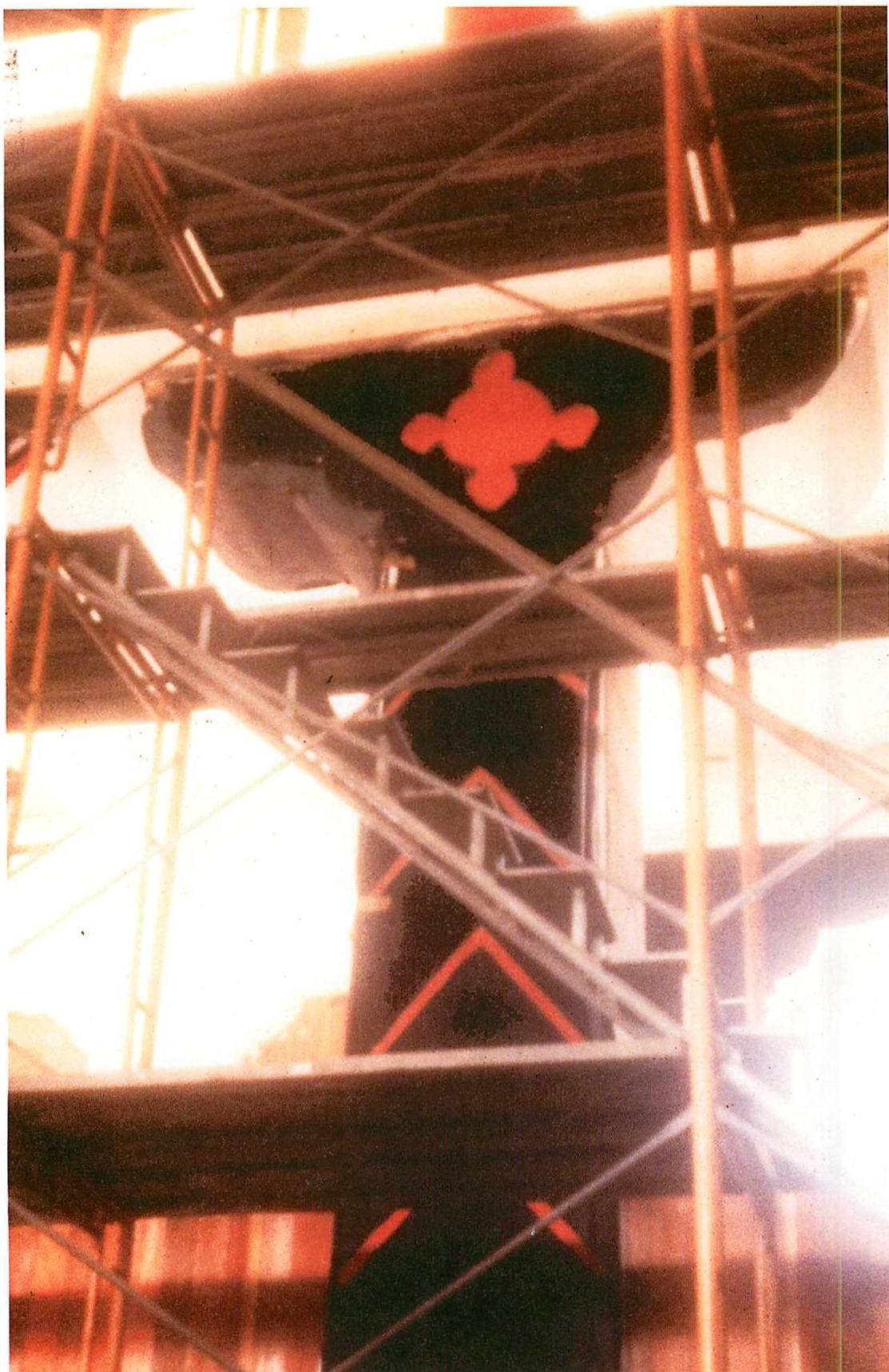

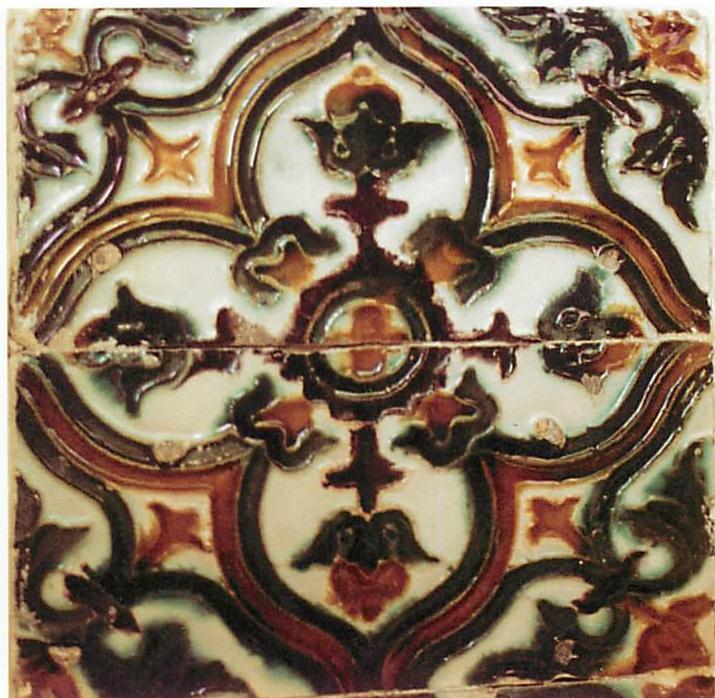

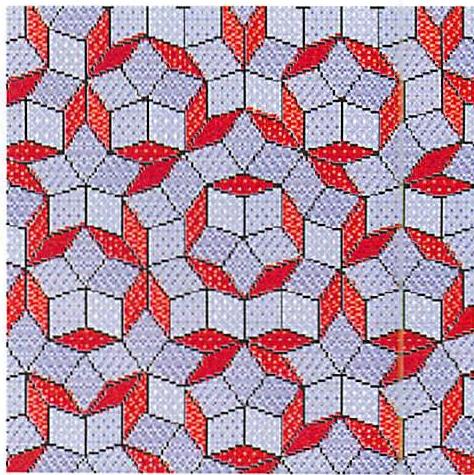

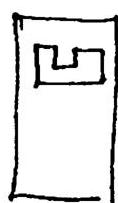

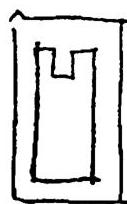

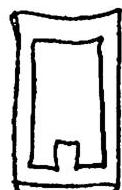

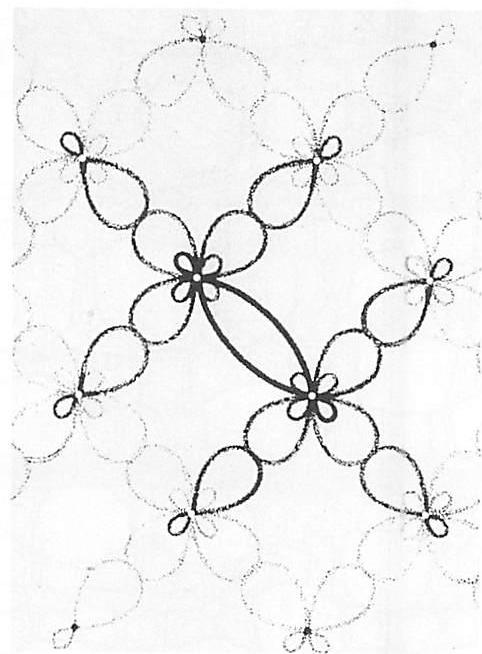

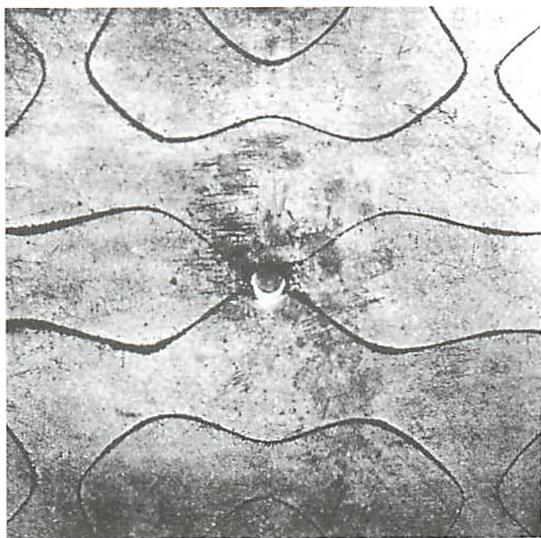

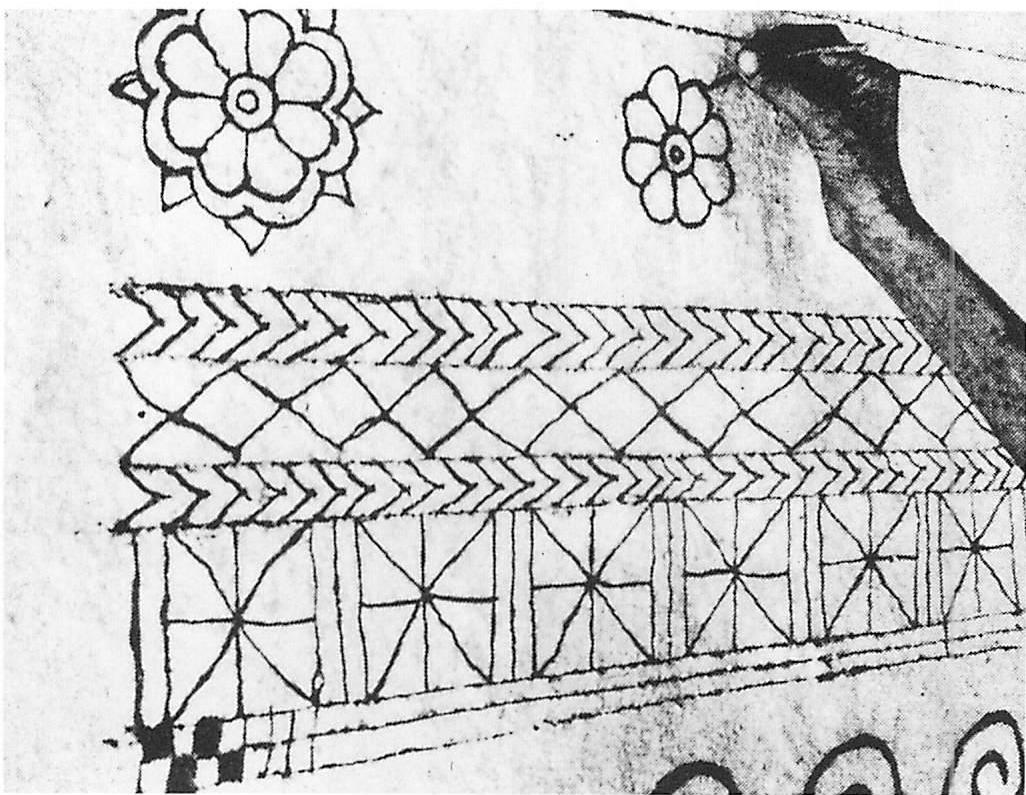

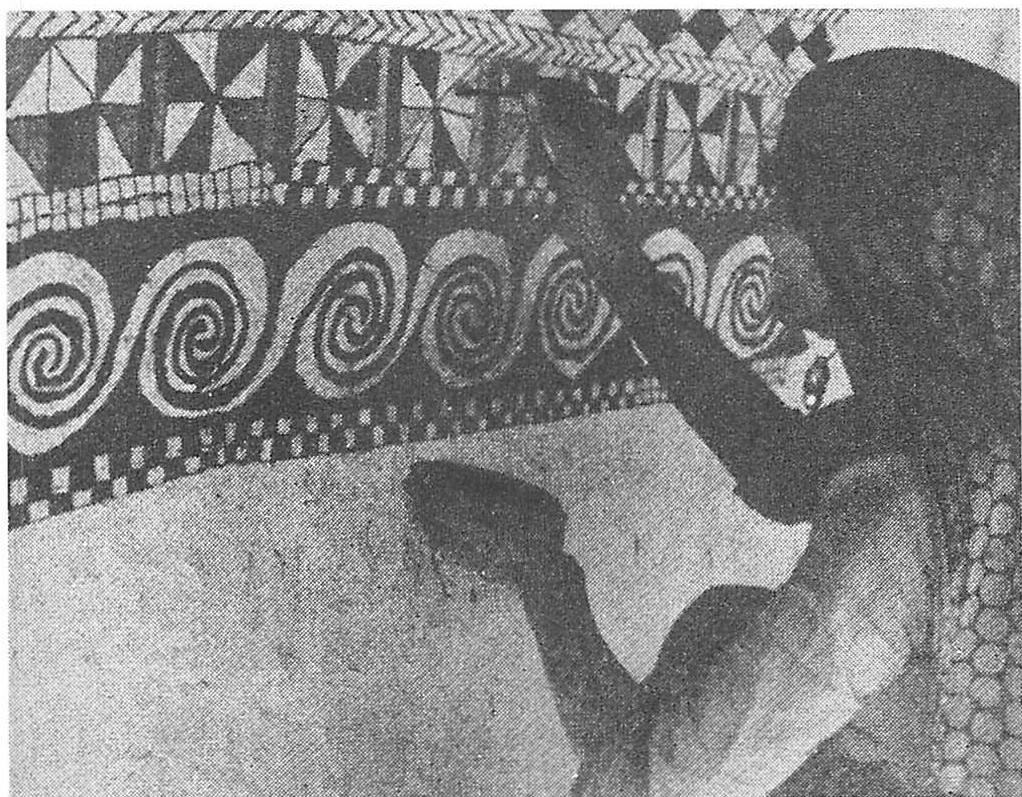

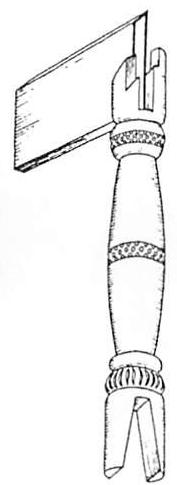

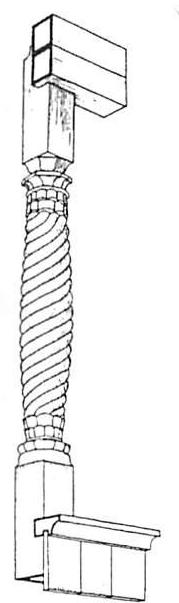

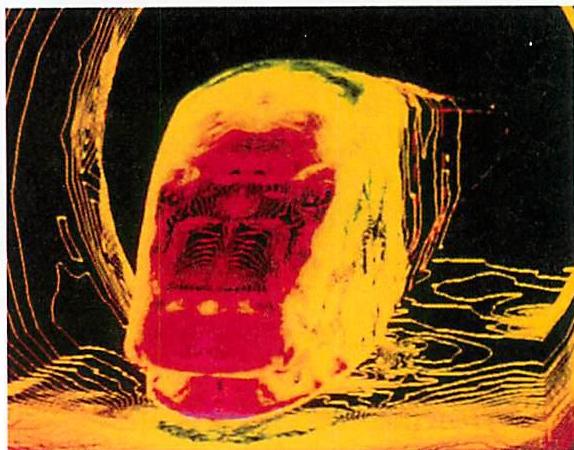

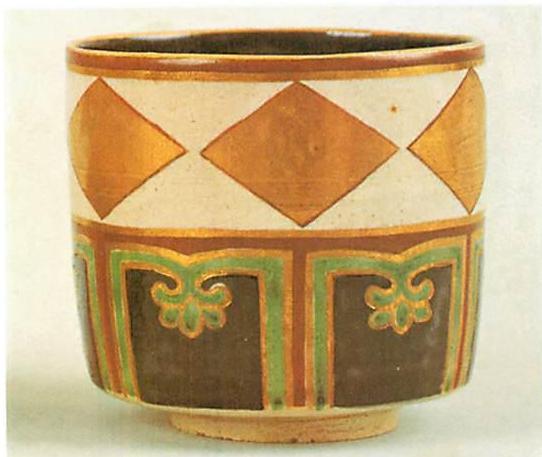

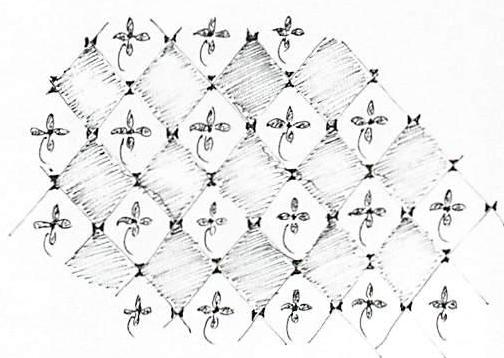

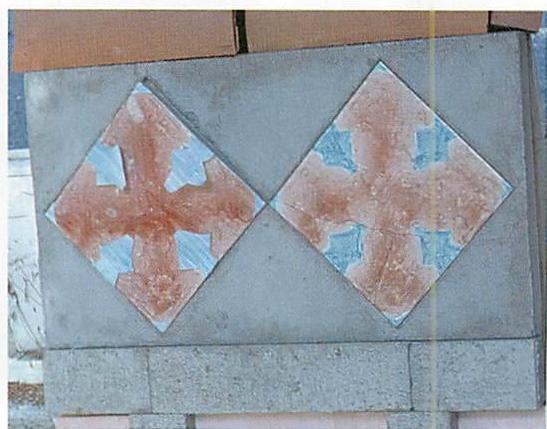

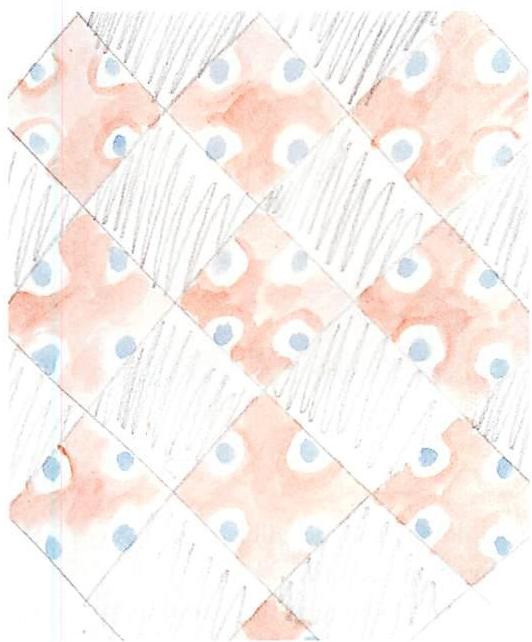

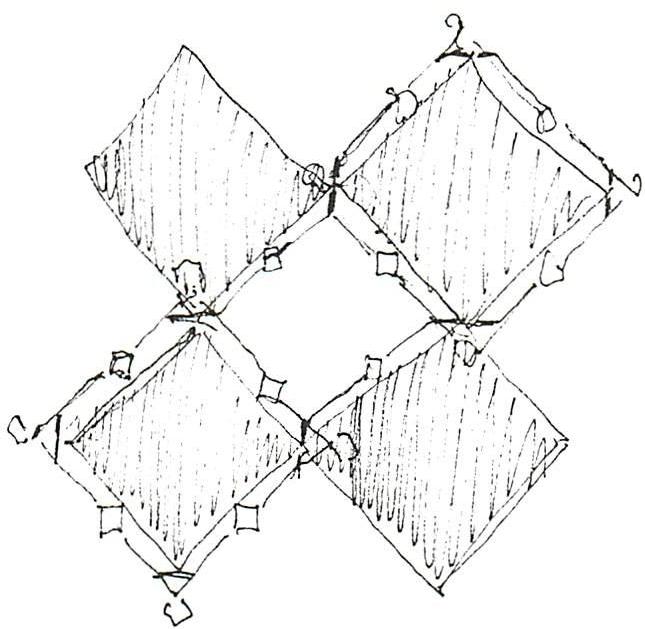

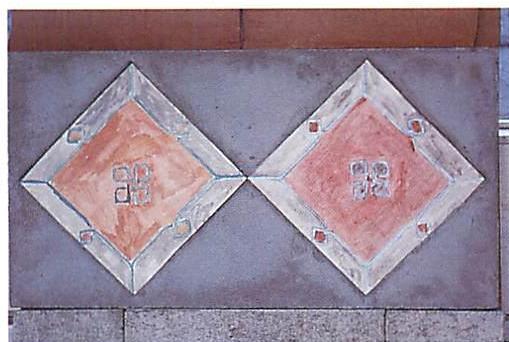

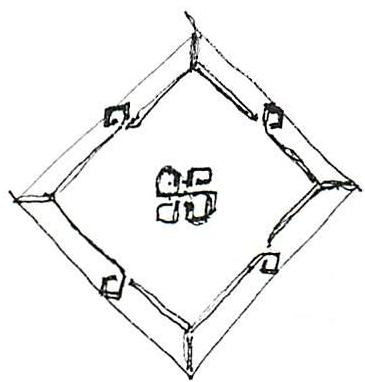

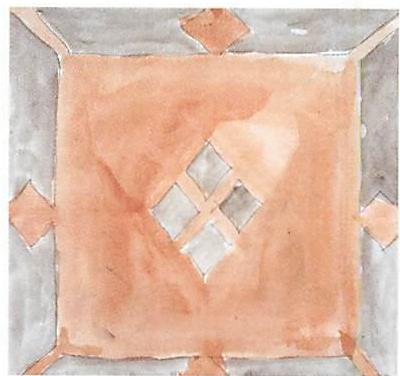

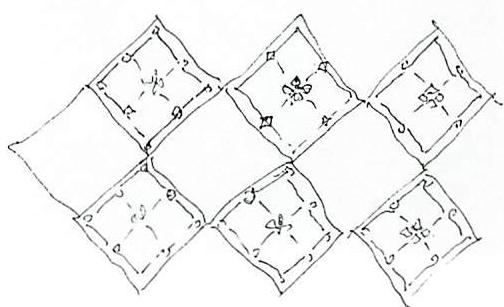

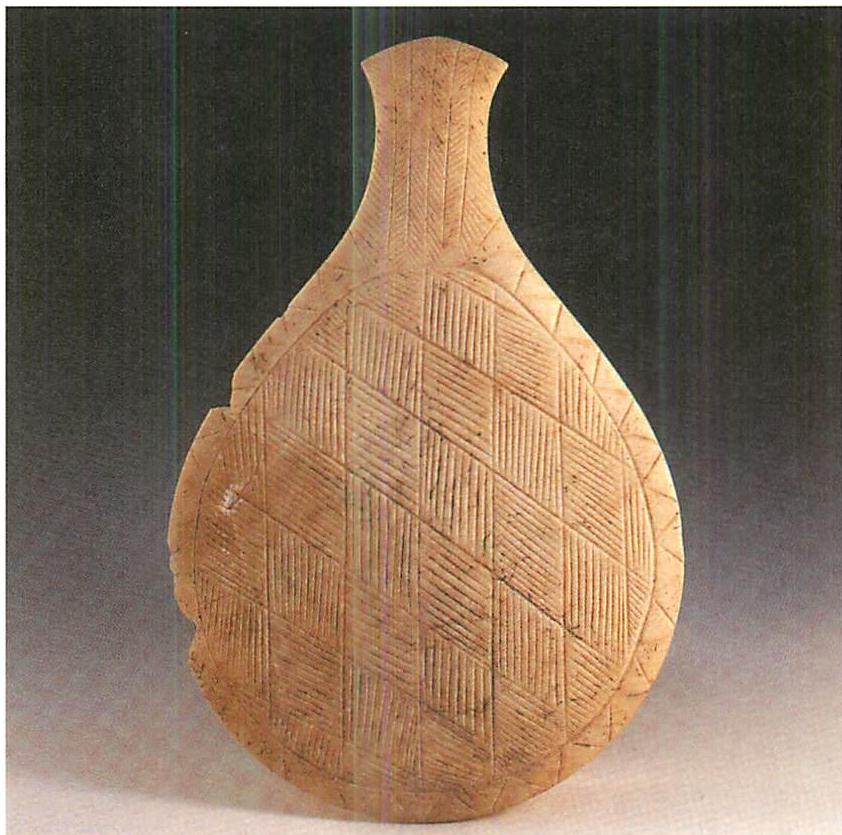

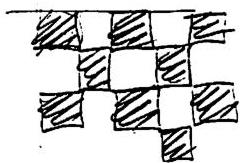

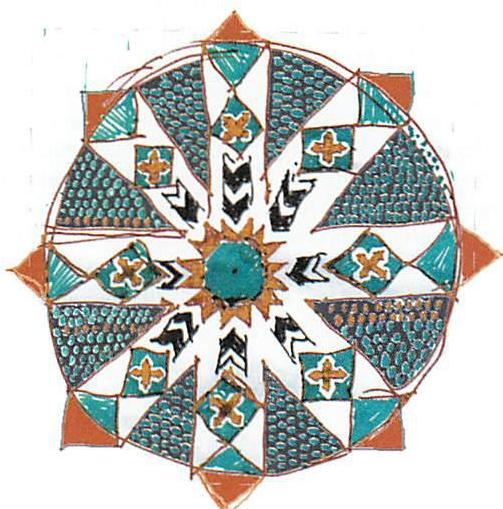

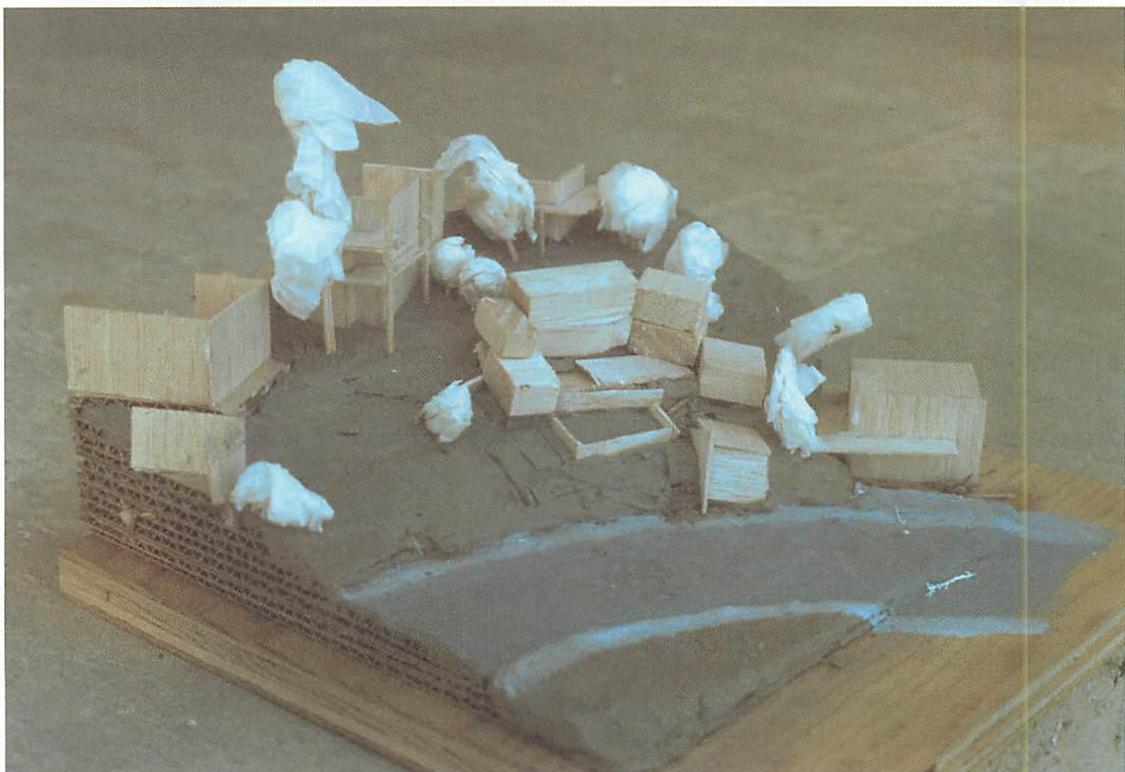

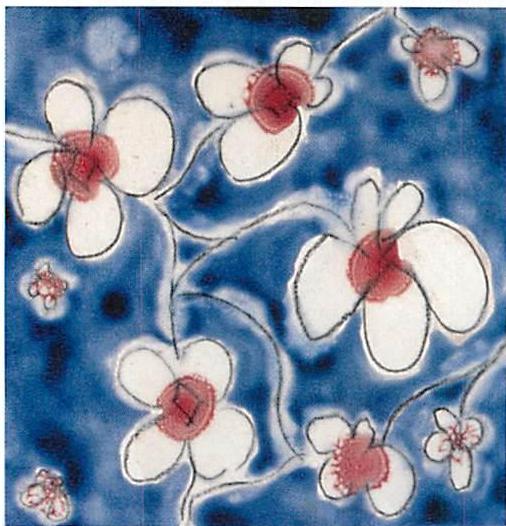

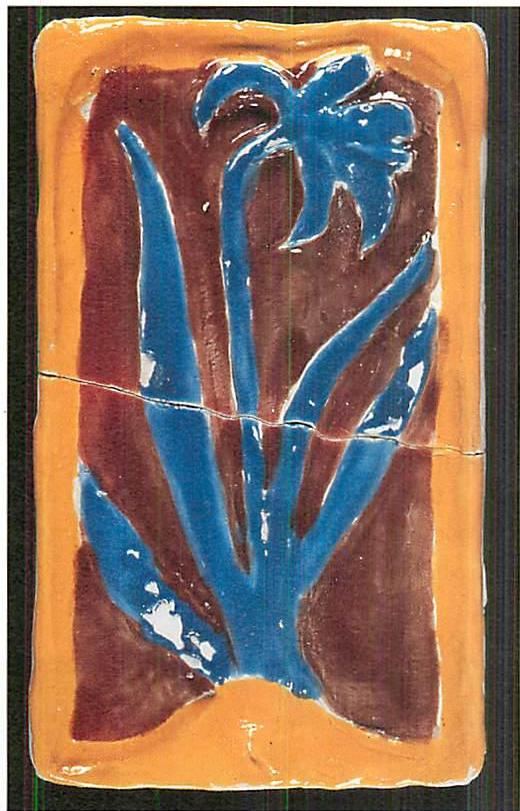

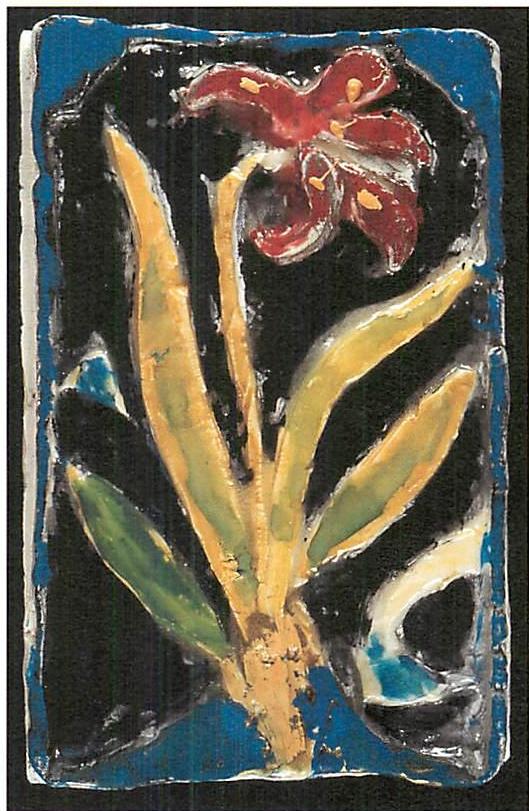

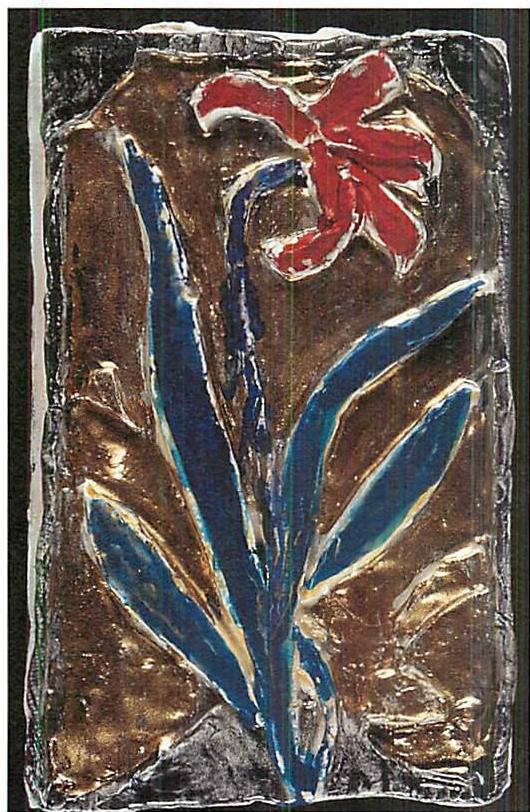

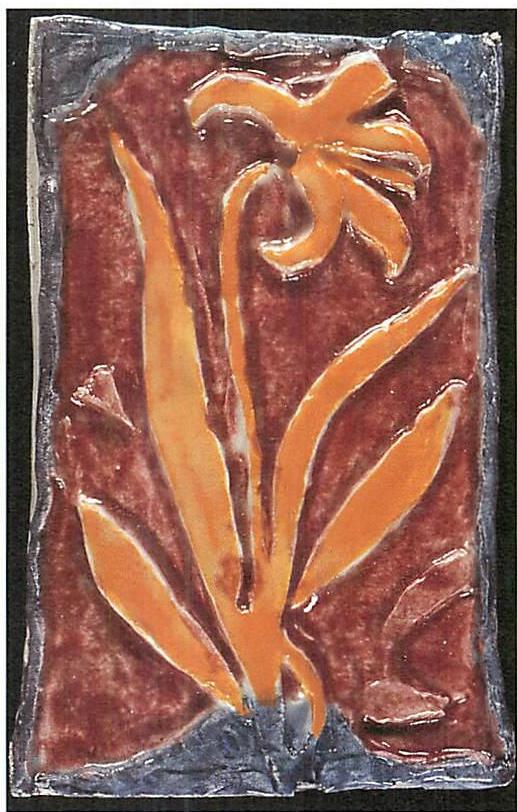

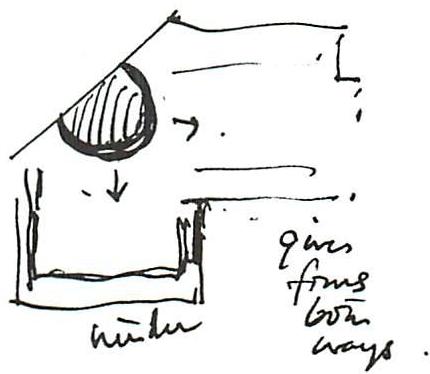

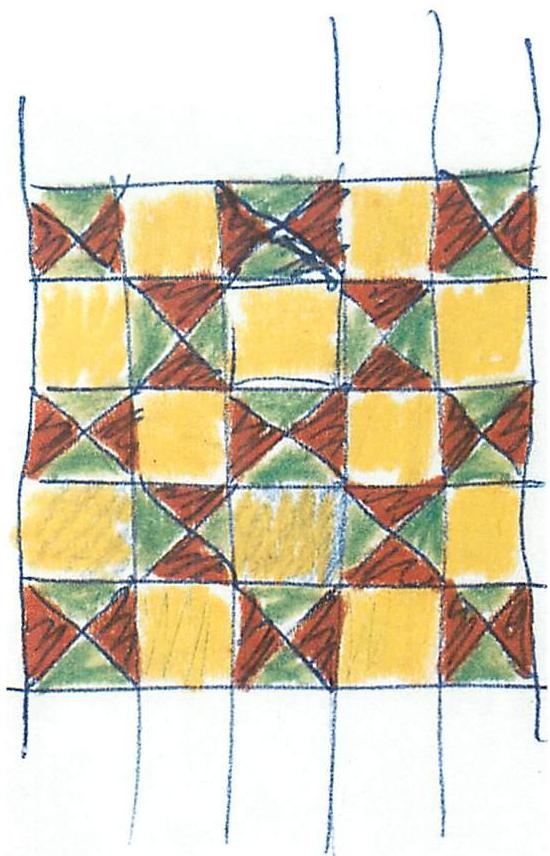

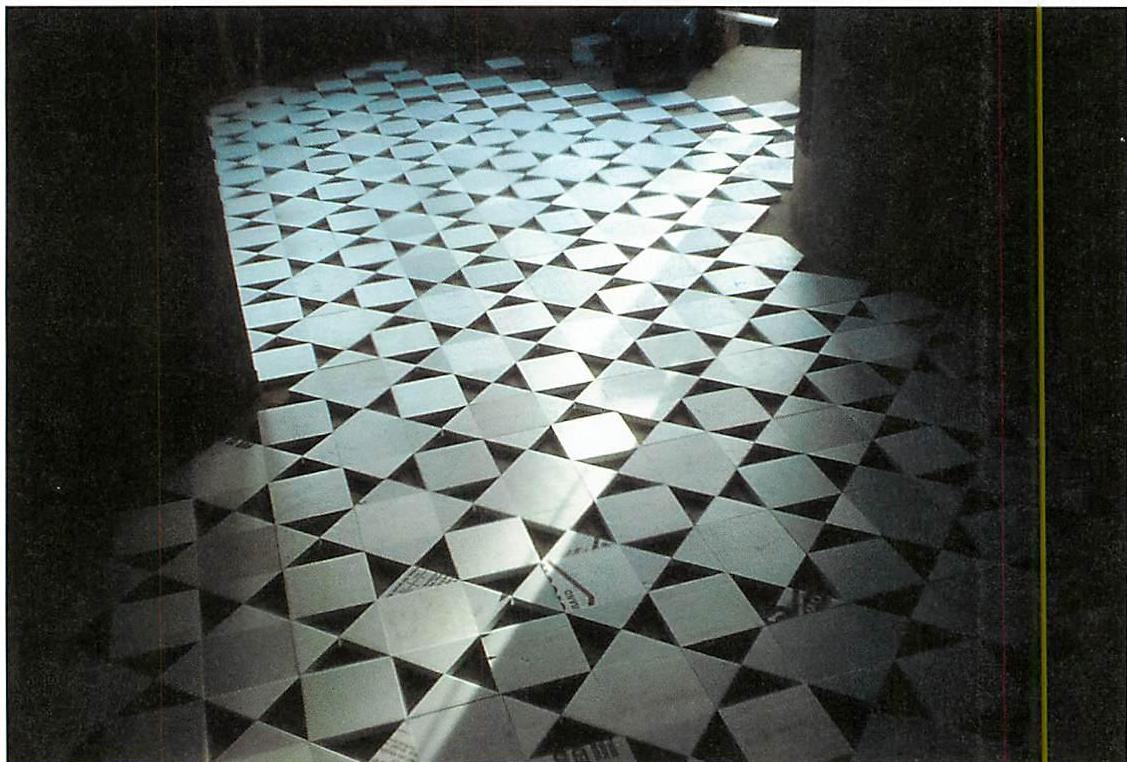

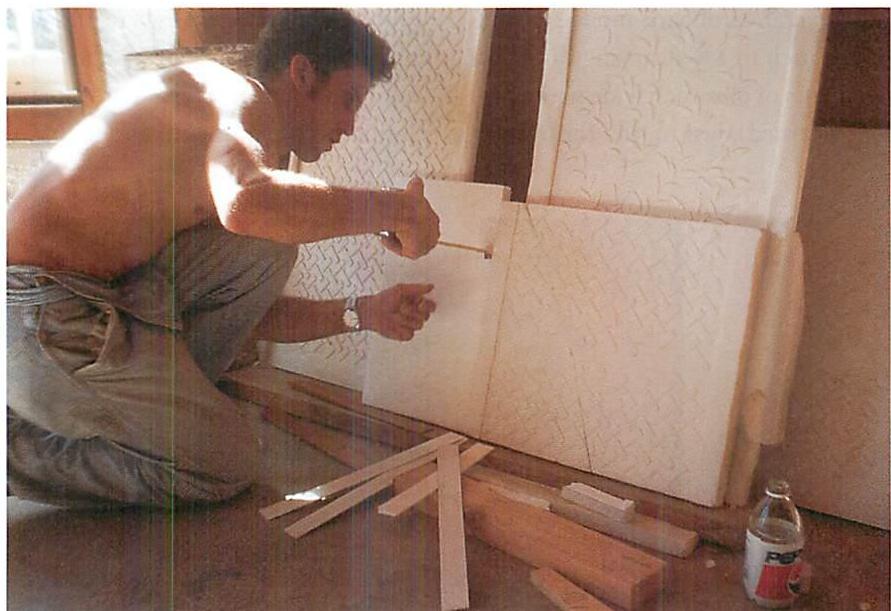

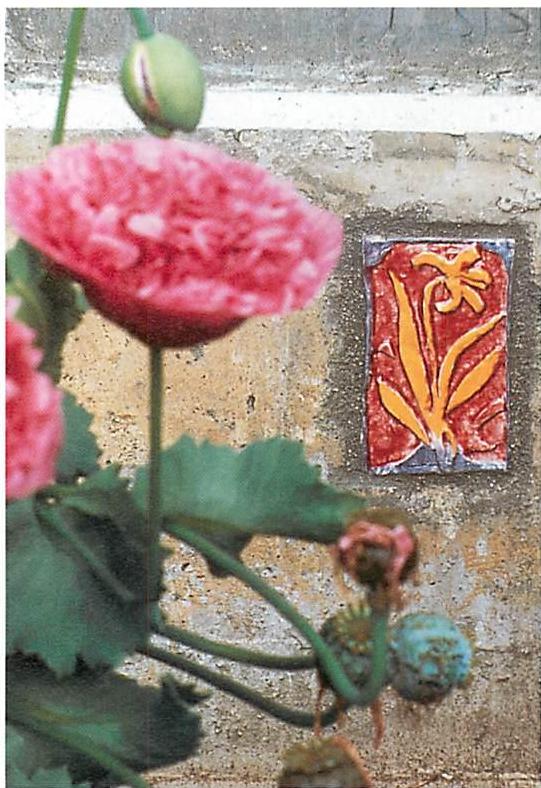

Look at this Hispano-Moresque tile of the 15th century. When we first look at it, we see a beautiful design, harmonious, orderly, well-conceived, beautiful space and color. In contemporary terms, all this would appear to be part of the design of the tile, since it is the geometry of the finished tile, it seems to us, that causes this. We think of its beauty as a result of design.

But when I handled this tile, looked at its surface, held its weight, looked at the glaze, and started to ask myself how I would make a tile like this, the thing took on quite a different character. I saw that the particular lines of the design are formed by raised ridges in the clay. The separate colors of the different glazes are kept separate by these ridges, so that the liquid glaze, at the temperature of the kiln, cannot "run." As I thought more about how to do it—if I were actually making such a tile—I began to see that the sharp, almost hard design, the brilliant separation of glazes which makes the colors beautiful, and even the design itself, the character of straightness, curvature, and the formal quality of the line, are all by-products of a

particular kind of process which must be used to make such a tile.

I believe the design was made by laying thick rope into the soft clay. It is the rope which allowed the maker form such complex shapes, with perfect parallel lines, and perfect half-round troughs. In my studio my assistant went further to understand how it had been done, and made a clay impression of the tile's surface in reverse. This reverse—a raised embossed impression taken in modeling clay—was even more impressive, and more beautiful than the tile itself. I realized that this—the negative impression—must have been the actual thing which the maker made, and that the tile was then cast from it in clay.

The further I went to understand the actual process which had been used to make the tile, the more I realized that it was this process, more than anything, which governs the beauty of the design. Perhaps nine-tenths of its character, its beauty, comes simply from the process that the maker followed. The design, what we nowadays

think of as the design, followed. It was almost a residue from the all-important process. The design is indeed beautiful, yes. But it can only be made as beautiful as it is within the technique, or process, used to make it. And once one uses this technique, the design — what appears as the sophisticated beauty of the design — follows almost without thinking, just as a result of following the process.

If you do not use this technique—process—you cannot create a tile of this design. An attempt to follow the same drawing, but with different techniques, will fall flat on its face. And if I change the technique (process), then the design must change, too. This design follows almost without effort from this technique. It is the process, not the design, that is doing all the hard work, and which is even paving the way for the design.

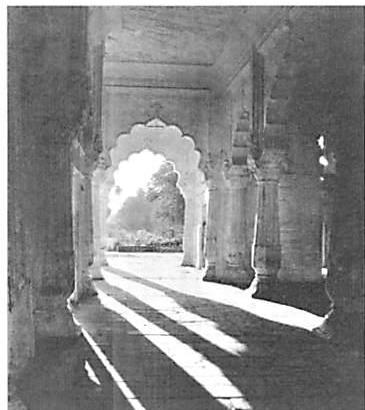

Thus the making, the physical processes of shaping, carving, drying, glazing, and firing the tile, are the ways in which this tile gets its form, its life, even its design. The "design" of this beautiful work is not more than a tenth of what gives it its

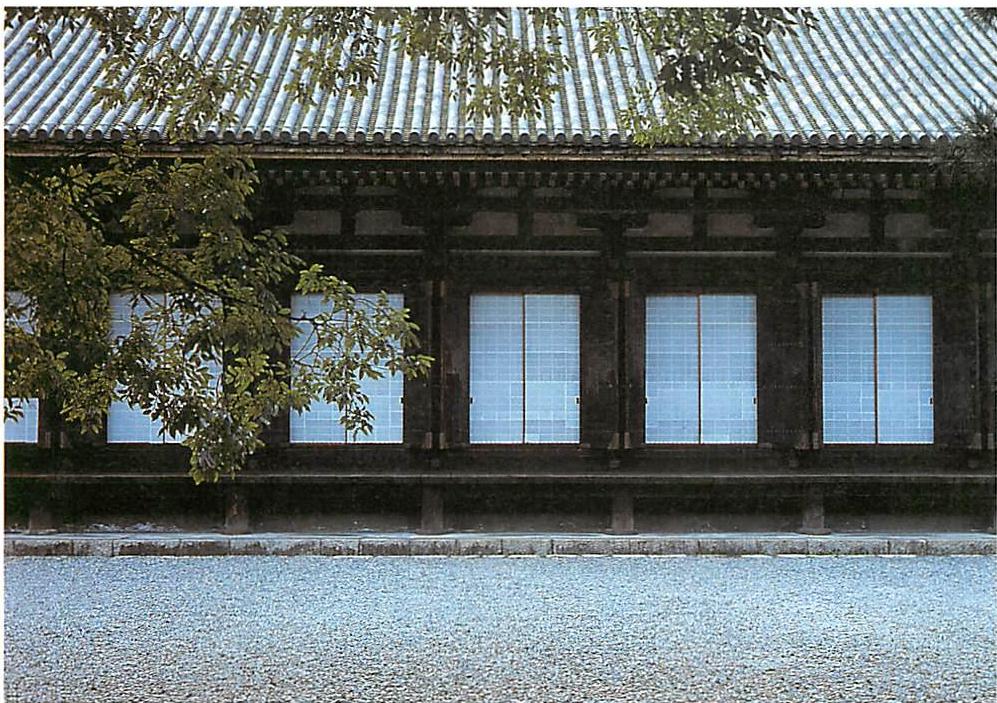

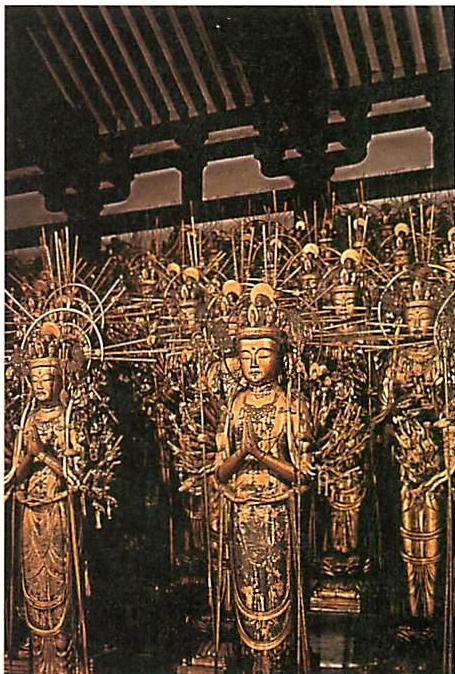

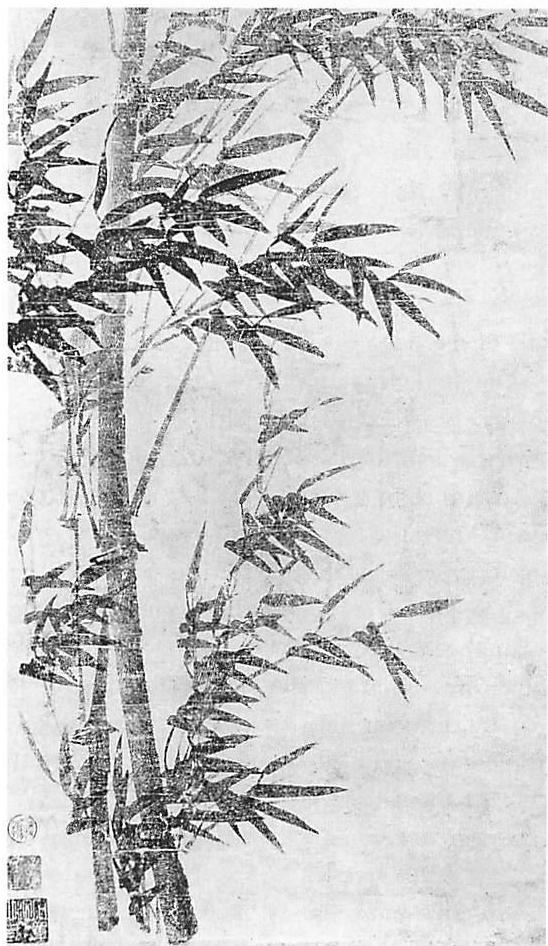

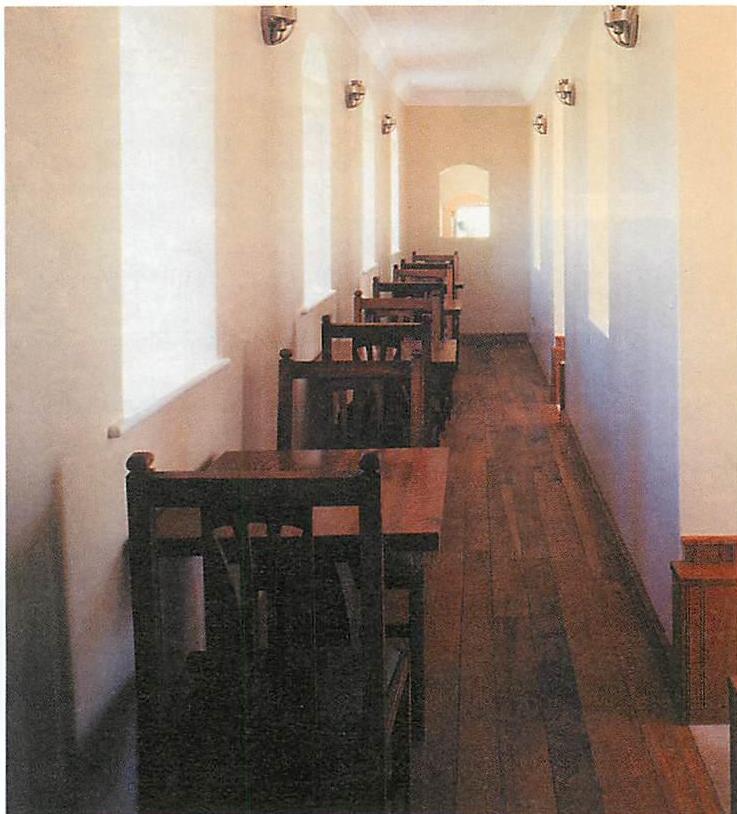

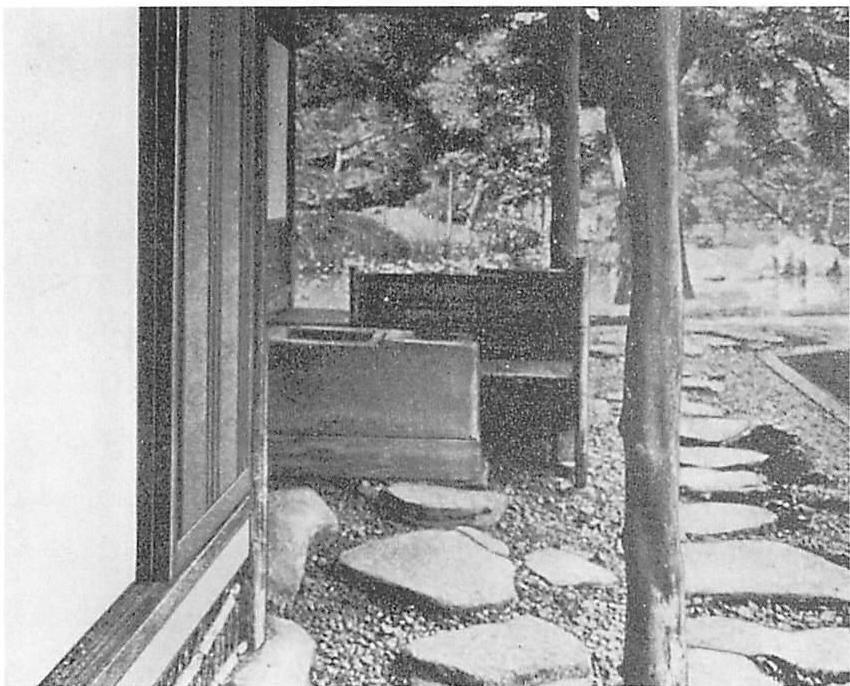

life. Nine-tenths come from the process. We see the same phenomenon in a far more complex work from 13th-century Kyoto. In San-ju-san Gen Do, the temple of the thirty-three bays, we see the imprint of years, the imprint of care in the pieces of wood that have been lovingly matched to their position so well that seven hundred years later they still impress the heart. It is the mark of the plane on the wood which makes the wood, hundreds of years later, touch our hearts. It is the process used by the temple priests to lay out the foundations and cornerstones which places the building so beautifully in the land. It is the care of the goldsmith—the carving process and the carving tools, the process of making the mold—which gives each of the one thousand buddhas its unique personality, yet allows it to be ultimately the same and so, capable of teaching us, through one thousand manifestations, that we feel the true nature of all things.

This gradual rubbing together of phenomena to get the right result, the slow process of getting things right, is almost unknown to us today.

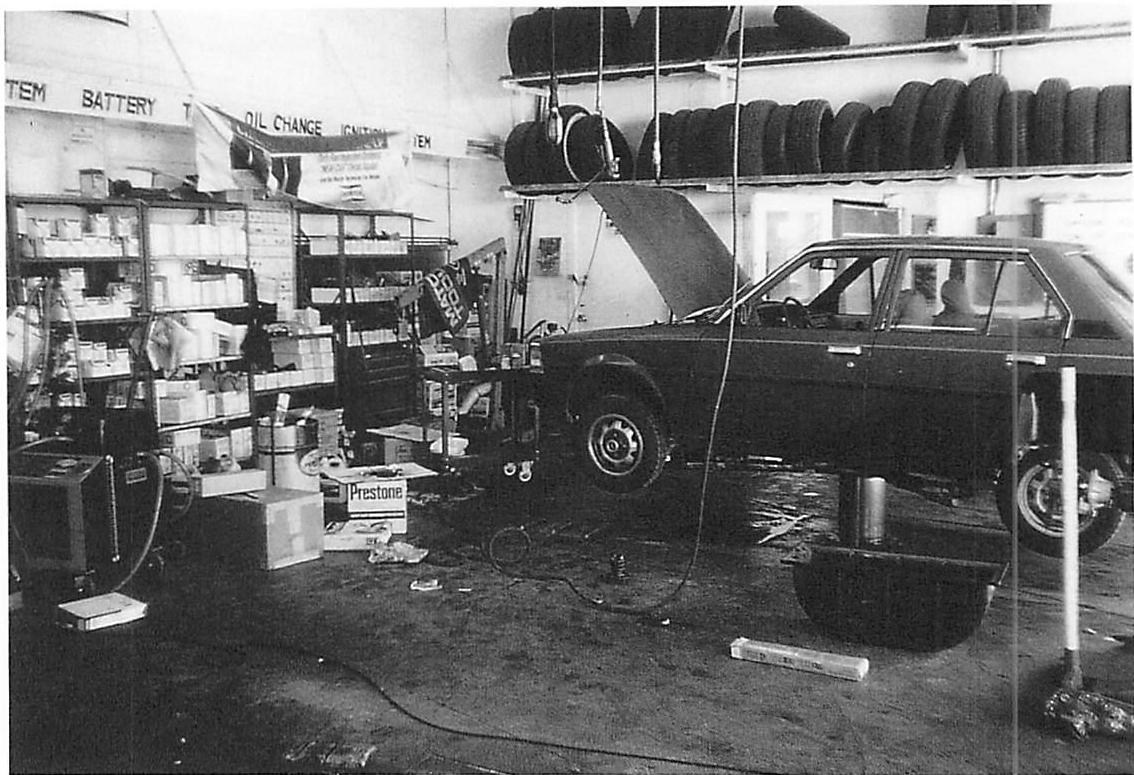

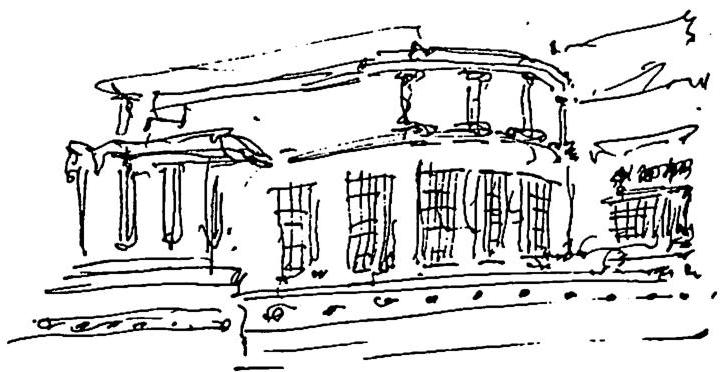

5 / OUR MECHANIZED PROCESS

During the 20th century, we became used to something very different.

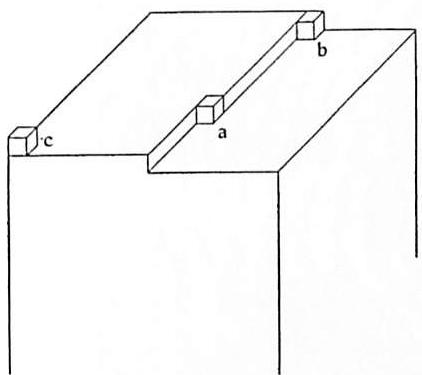

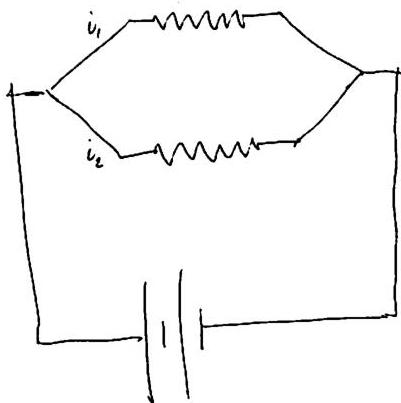

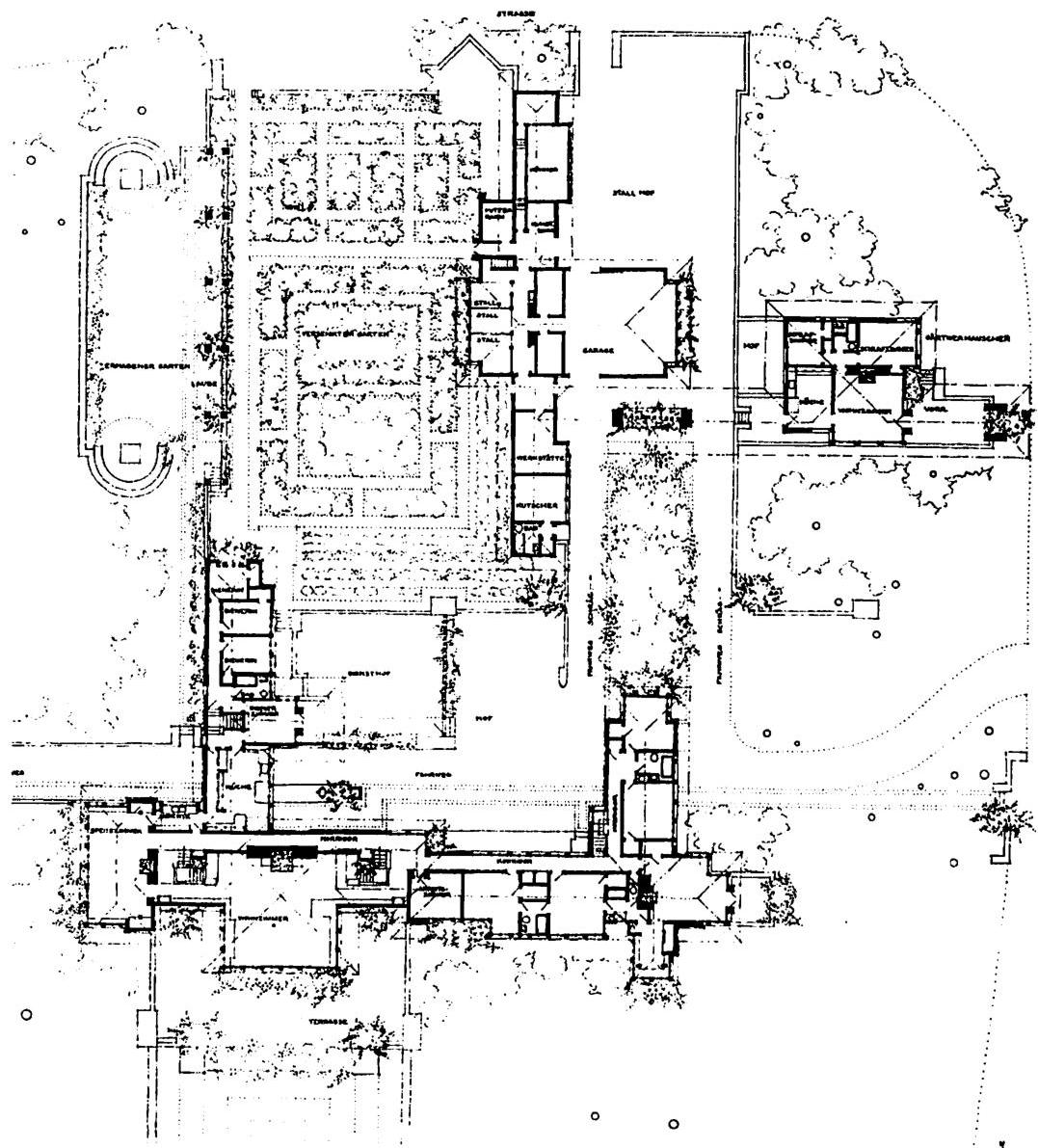

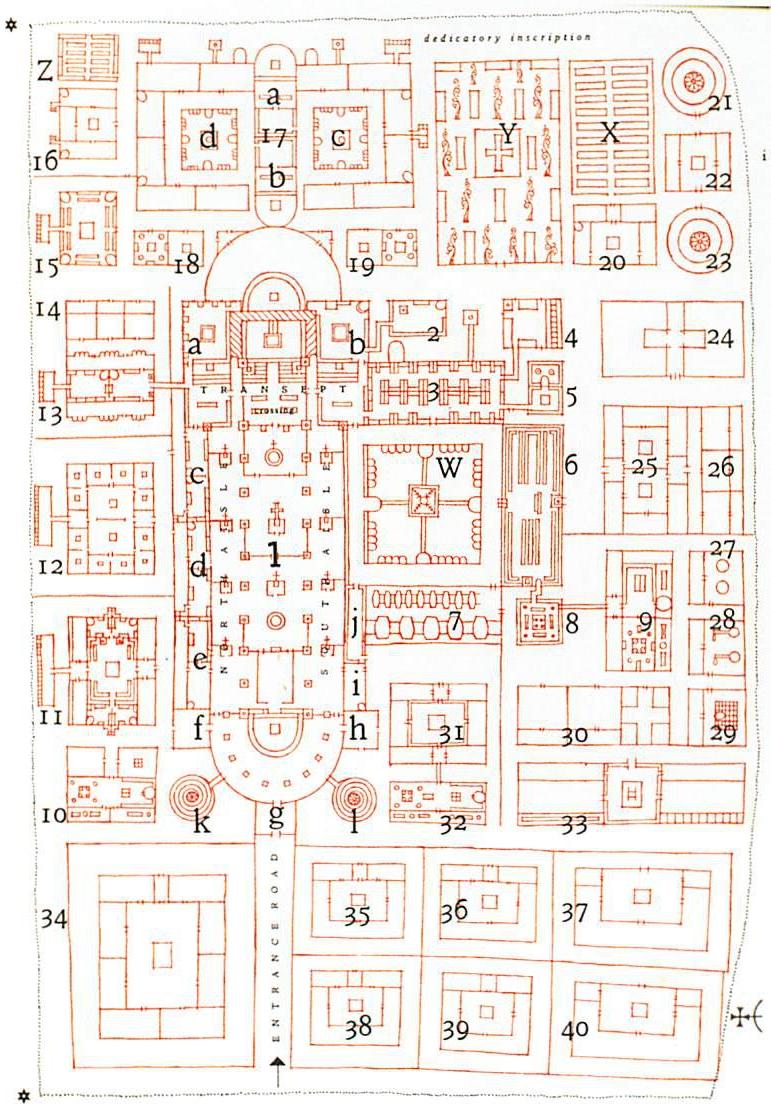

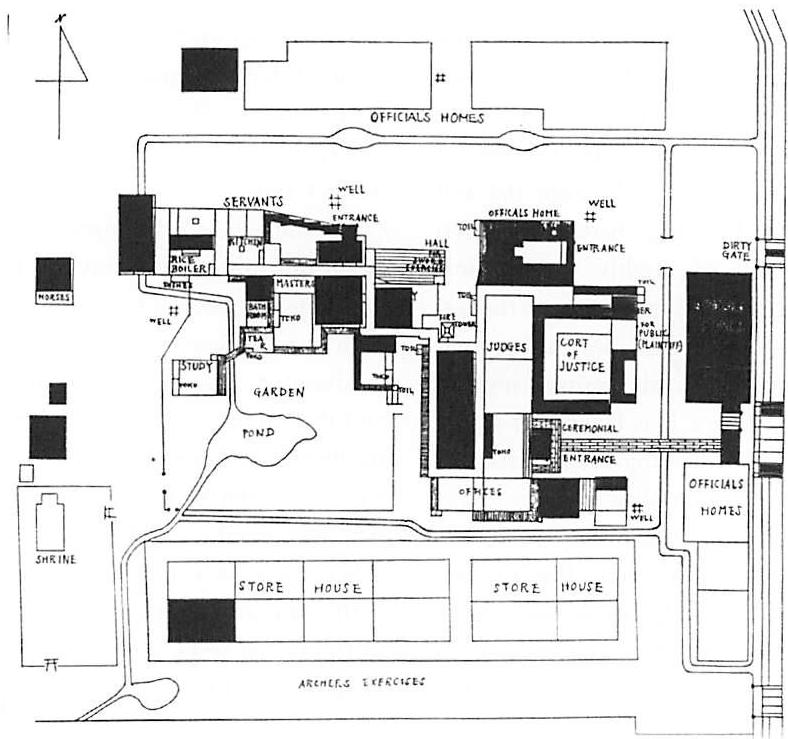

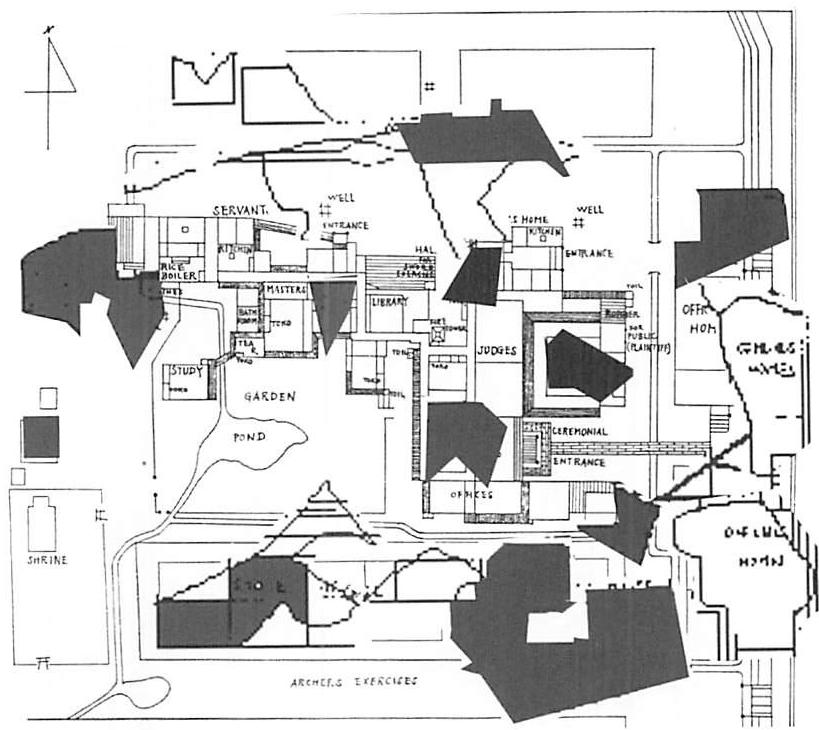

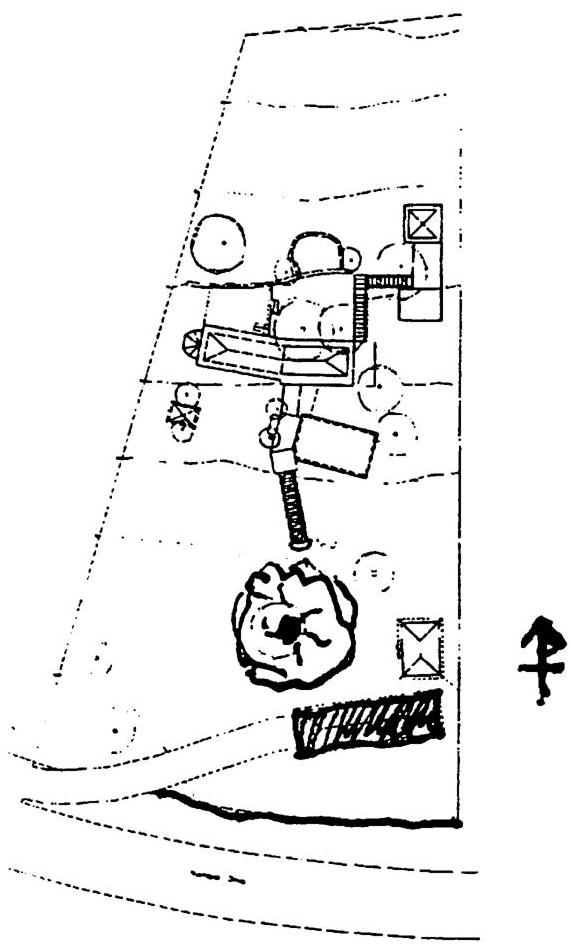

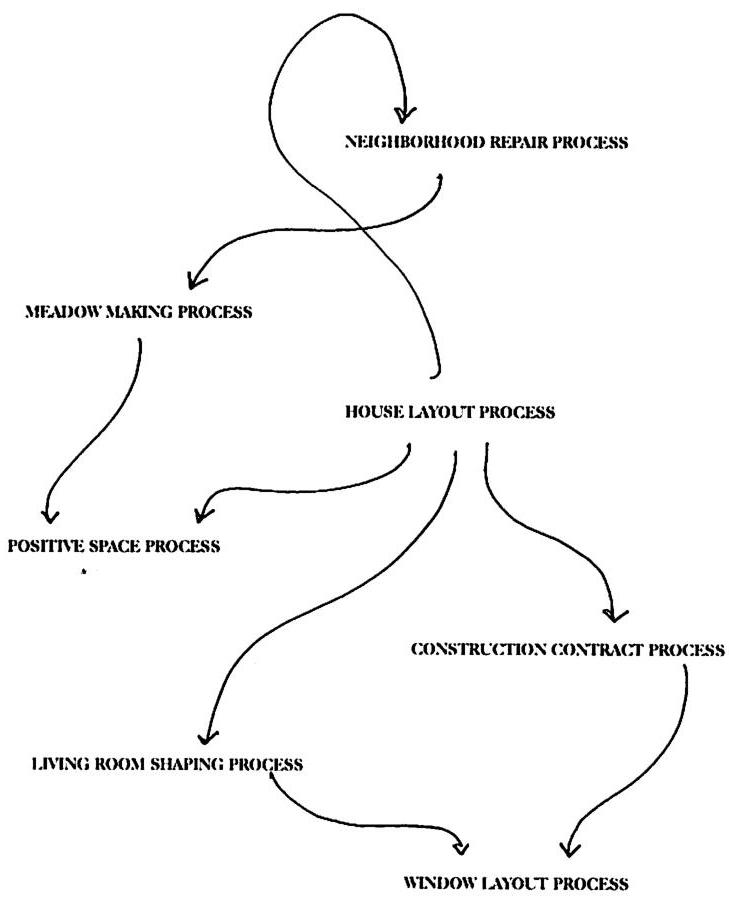

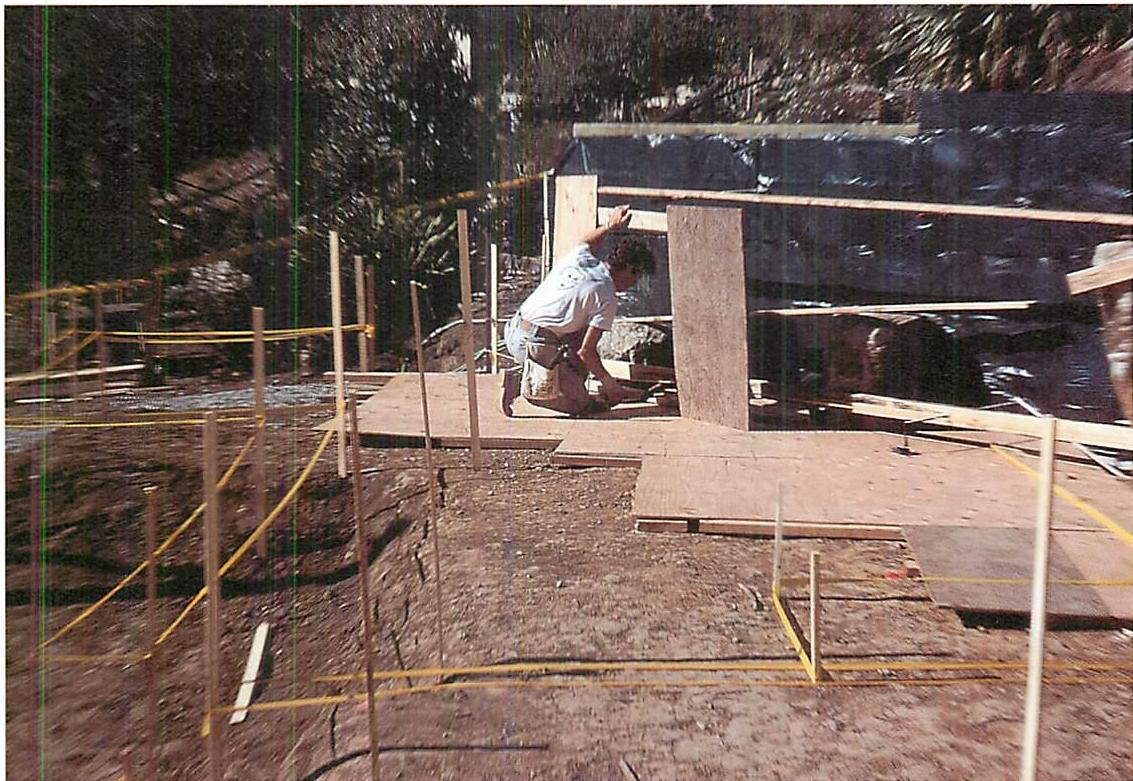

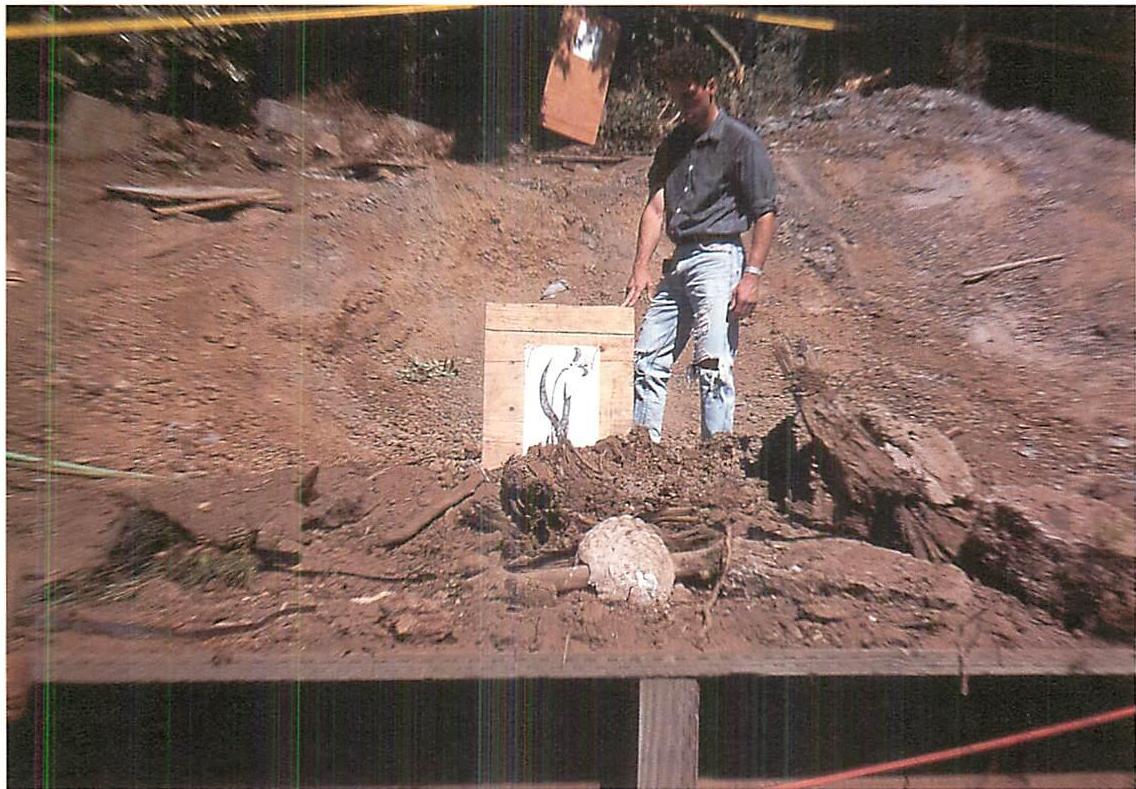

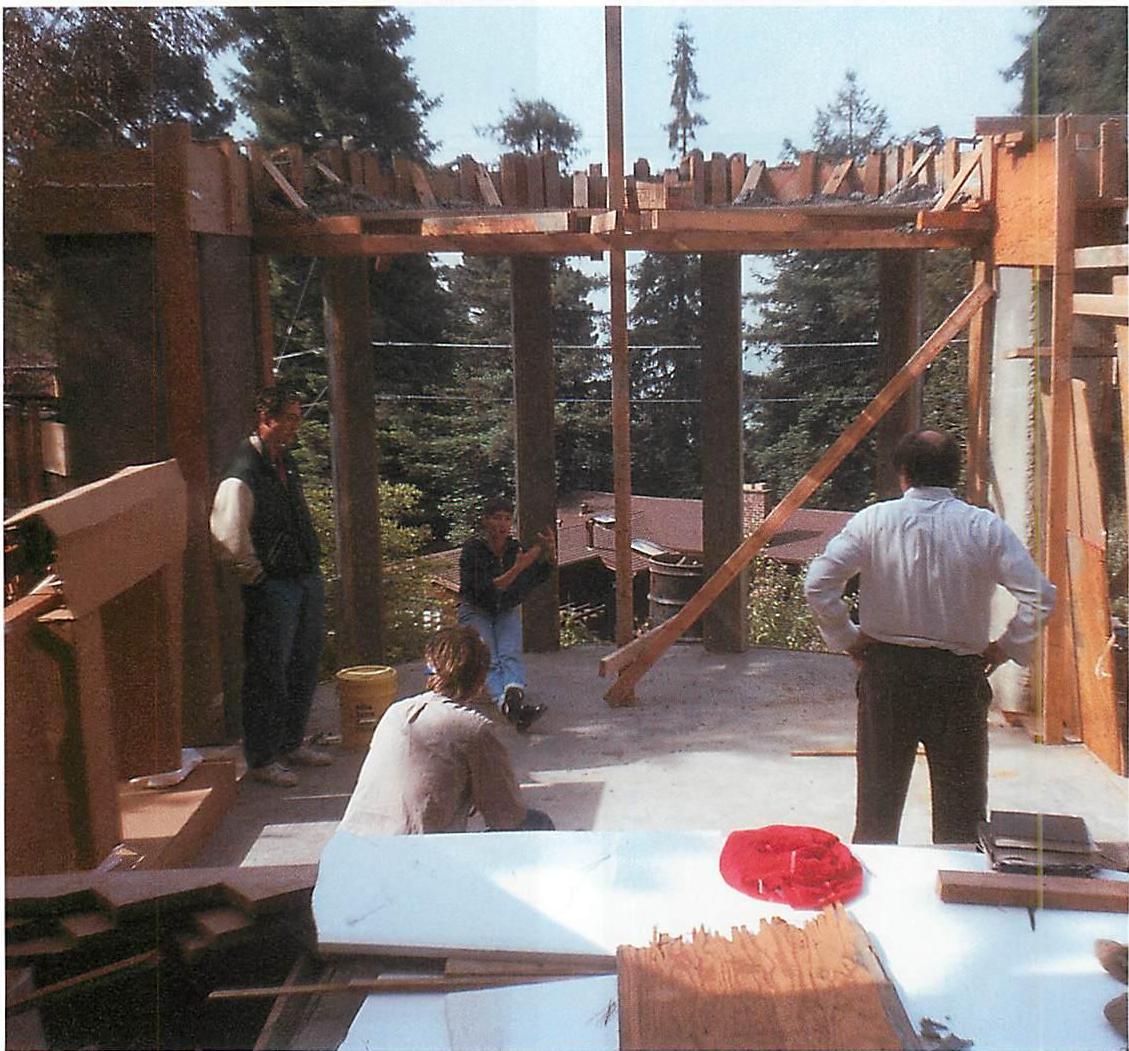

Consider the "normal" building process we have become used to in recent decades. A client specifies a program in which building areas are mechanically set out as requirements. In the case of a large building, this program is then made more precise (and often more rigid) by a professional programmer who sets it forth arithmetically in a table of square footages. An architect designs the building at a drawing table and is held to the program, rigidly, not to the evolving whole. The drawings are then checked by an engineer who is separate from the process and responsible for making the building stand up. A soils engineer very possibly works out the foundation, separately again. The final engineering drawings are then checked by a building inspector and by a zoning officer—again a separate process. In many cases, the zoning officer who checks them has not been to the site. Even if the officer has done a site visit, he or she has little or no authority to create any coherent relation between the building and the site, in relation to the site's special conditions. Once the drawings are approved, they are sent out to bid, by a contractor who has not been part of the design process, looks only at the drawings, but shares none of the vision. The drawings are also checked by a bank. The individual parts of the drawings may be sent out to bid by subcontractors, who are even more remote from the task at hand. Many of the ob

jects, components, which will be used in the construction of the building are factory-made. They have been designed and constructed with no knowledge of the building at all; they are mentally and factually separate from its existence, but are brought into play only by a process of assembly.

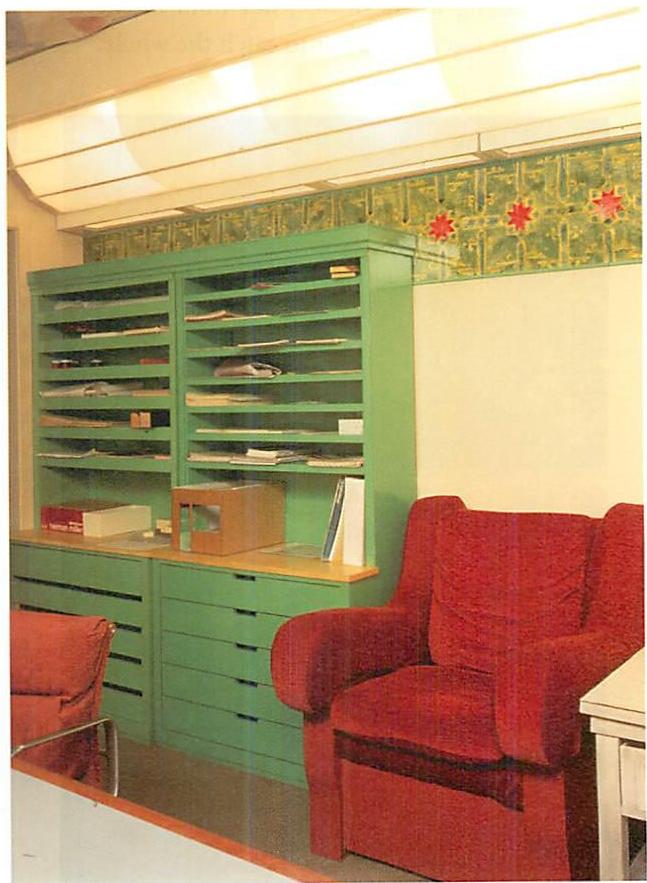

During the building process, corrections cannot be made without huge expense to the client. Thus the assembly process is insensitive to almost any new wholeness which appears during construction. The landscape work is done by a separate architect, who specializes in plants. The actual gardening—that is, the preparation of the ground, planting of trees, flowers—is done by yet another person acting under orders, and once again contractually removed from the human feeling, light, and action of the building.

The interior, very often, is done by yet another person—an interior decorator. This person, again remote from any previous reality, will also assemble pre-constructed components and modules to try and produce a whole. But the elements are, at the end, almost inevitably separate and cold in feeling, harsh in content, without origin in human meaning. They do not reflect the feelings of the building's occupants; nor do they arise naturally from the wholeness of the building shell and from the seeds of a direction which that shell already contains. Even the building's paint is often applied as an afterthought, as if it were an independent act. And the very paint, itself, is once again chosen from among a system of mechanically component-like colors, none of which was conceived in the context of the building, but which exist, precooked, in a catalog.

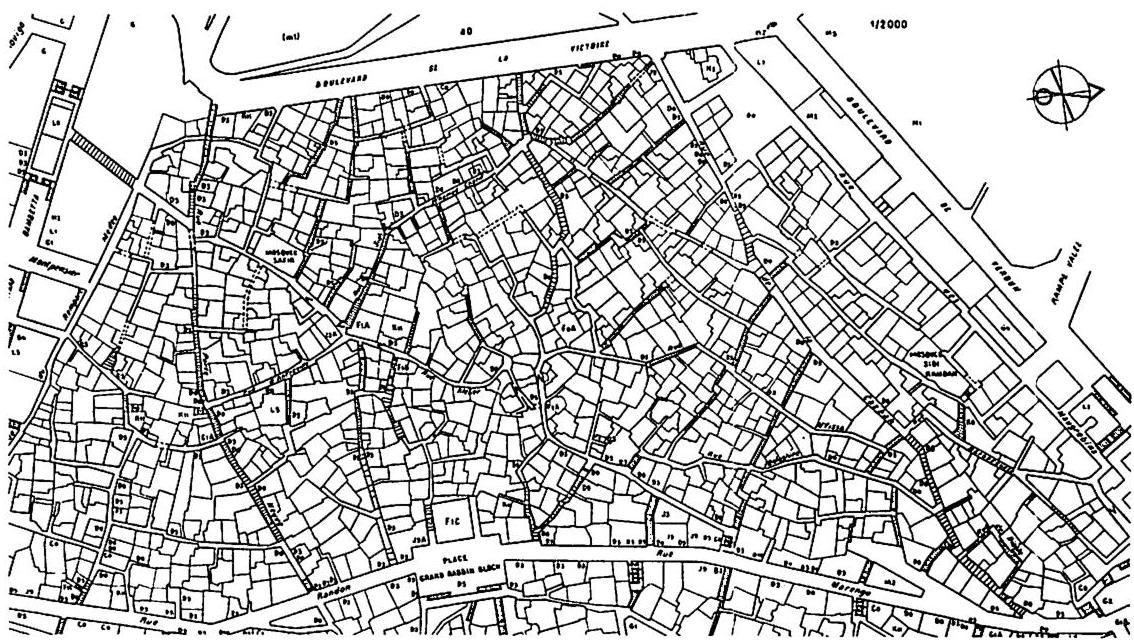

Present-day town-planning practice—mainly based on zoning—is equally mechanical in character. It is largely independent of the people most directly affected, and is controlled by appointed officials, who often do not even visit the site where a particular building is to be built. The zoning ordinance—a map of an imaginary future, used as a control device—is prepared by others. The process is based, in considerable part, on the needs of the developer-controlled,

profit-oriented marketplace, and on the assumption that agreement about deep value is impossible in principle. Achievement of subtle or spiritual character in a town under these conditions—which are a large-scale replica of the conditions surrounding smaller-scale mechanical building process—is once again hardly possible.

You might say of these examples, "But this surely is all process. Isn't that good?" The trouble is that it is mechanical process only, something which subverts the inner fire of true living process.

In a mechanistic view of the world, we see all things, even if only for convenience, as machines. A machine is intended to accomplish something. It is, in its essence, goal-oriented. Like machines, then, within a mechanistic view processes are always seen as aimed at certain ends. We think of things by the end-state we want, and then ask ourselves how to get there.

This mistake was widespread in the 20th century. For example, in the extreme 20th-century view of some mechanistic sociology, even kindness might have been seen as a way of achieving certain results: part of a bargain, or a social contract, which had the purpose of getting something.[10]

Real kindness is something quite different, something valuable in itself. It is a true process, not guided by the grasp for a goal, but guided by the minute-to-minute necessity of caring, dynamically, for the feelings and well-being of another. This is not trivial, but deep; sincerely related to human feeling; and not predictable in its end-result, because the end-result is not a goal. Unlike the goal-oriented picture, which is imposed intellectually on our substance as persons, real kindness is a process true to our essential human instinct and to our knowledge of what it means to be a person. But the machine-age view showed a process like kindness as being oriented toward a goal, just as every machine too has its purpose — its goal, what it is intended to produce.

Like the mechanical 20th-century view of kindness, the 20th-century mainstream view of

building was goal-oriented and mechanistic, aimed mainly at end-results, not on the inner good of processes. Building was viewed as a necessary way to achieve a certain end-result. The design drawn by the architect — the master plan drawn by the planner — was the purpose, these were the goals of the art. The process of getting to the goal was thought to be of little importance in itself, except insofar as it attained (or failed to attain) the desired goal.

The mechanistic view of architecture we have learned to accept in our era is crippled by this overly-simple, goal-oriented approach. In the mechanistic view of architecture we think mainly of design as the desired end-state of a building, and far too little of the way or process of making a building as something inherently beautiful in itself. But, most important of all, the background underpinning of this goal-oriented view — a static world almost without process — just is not a truthful picture. As a conception of the world, it roundly fails to describe things as they are. It exerts a crippling effect on our view of architecture and planning because it fails to be true to ordinary, everyday fact. For in fact, everything is constantly changing, growing, evolving. The human body is changing. Trees bear leaves, and the

leaves fall. The road cracks. People's lives change from week to week. The building moves with wind and rain and movement of the earth. Buildings and streets and gardens are modified constantly while they are inhabited, sometimes improved, sometimes destroyed. Towns are created as a cooperative flow caused by hundreds, even millions, of people over time.

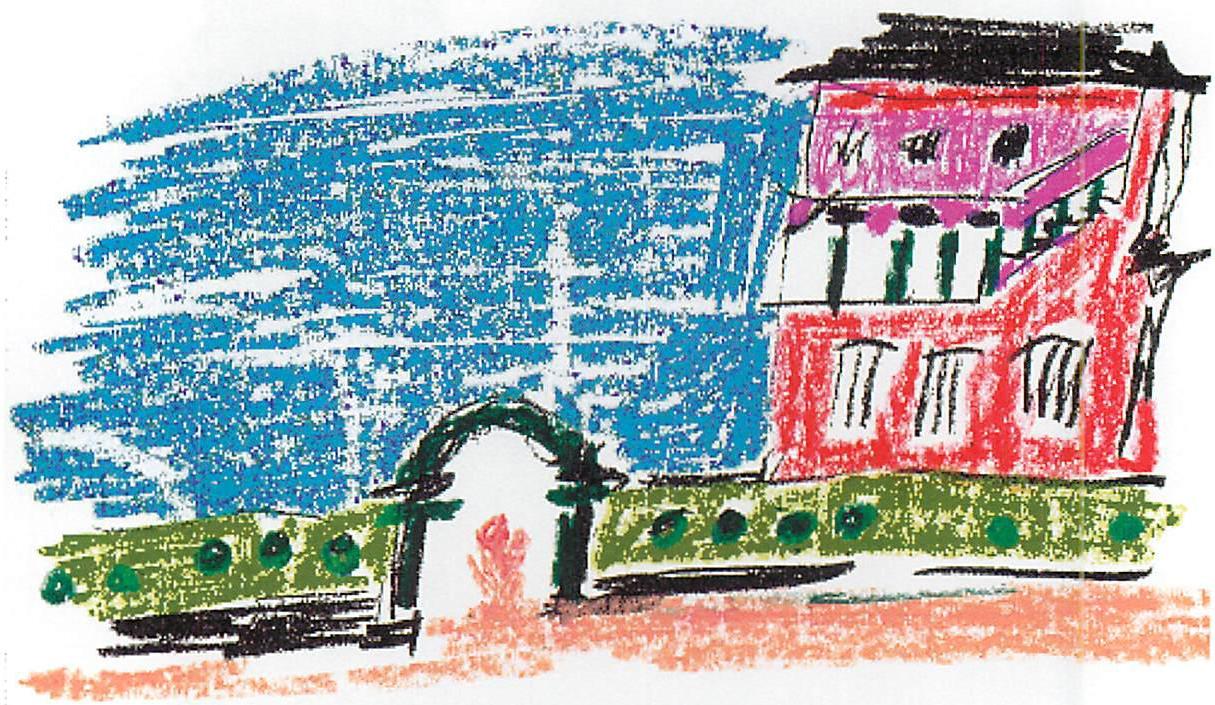

Why is this process-view essential? Because the ideals of "design," the corporate boardroom drawing of the imaginary future, the developer's slick watercolor perspective of the future end-state, control our conception of what must be done—yet they bear no relation to the actual nature, or problems, or possibilities, of a living environment. And they are socially backward, since they necessarily diminish people's involvement in the continuous creation of their world.

In all this, process is still not present as something essential, only as something mechanical.[11] In our profession of architecture there is no conception, yet, of process itself as a budding, as a flowering, as an unpredictable, unquenchable unfolding through which the future grows from the present in a way that is dominated by the goodness of the moment.

6 / POSSIBILITY OF A NEW VIEW OF ARCHITECTURAL PROCESS

I shall argue that every good process in architecture, and in city planning also, treats the world as a whole and allows every action, every process, to appear as an unfolding of that whole. When living structure is created, what is to be built is made consistent with the whole, it comes from the whole, it nourishes and protects the whole.

We may get some inkling of this kind of thing by considering what it means to design a building, and to compare it with what it means to make a building. Naively, I make a building if I actually do it myself, do it with my own hands.

This sounds like fun. But of course that is impossible for all but the very smallest buildings. More deeply, what it means for me to make a building is that I am totally responsible for it. I am actually responsible for its structure, its materials, its functioning, its safety, its cost, its beauty, everything. This is in marked contrast with the present idea of architecture, where as an architect I am definitely not responsible for everything. I am only responsible for my particular part in the process, for my set of drawings, which will then function, within the system, in a strictly limited fashion that is shut

off from the whole. I have limited responsibility. Like a bureaucrat, I play my role, but “don’t ask me to be responsible for anything — I am just doing my job.”

When I make something, on the other hand, I am deeply involved with it and responsible for it. And not only I. Whether I am head of some project, or a person making some small part of it, the feeling of total responsibility is on my shoulders. In a good process, each person working on the building is — and feels — responsible for everything. For design, schedule, structure, flowers, feeling — everything.

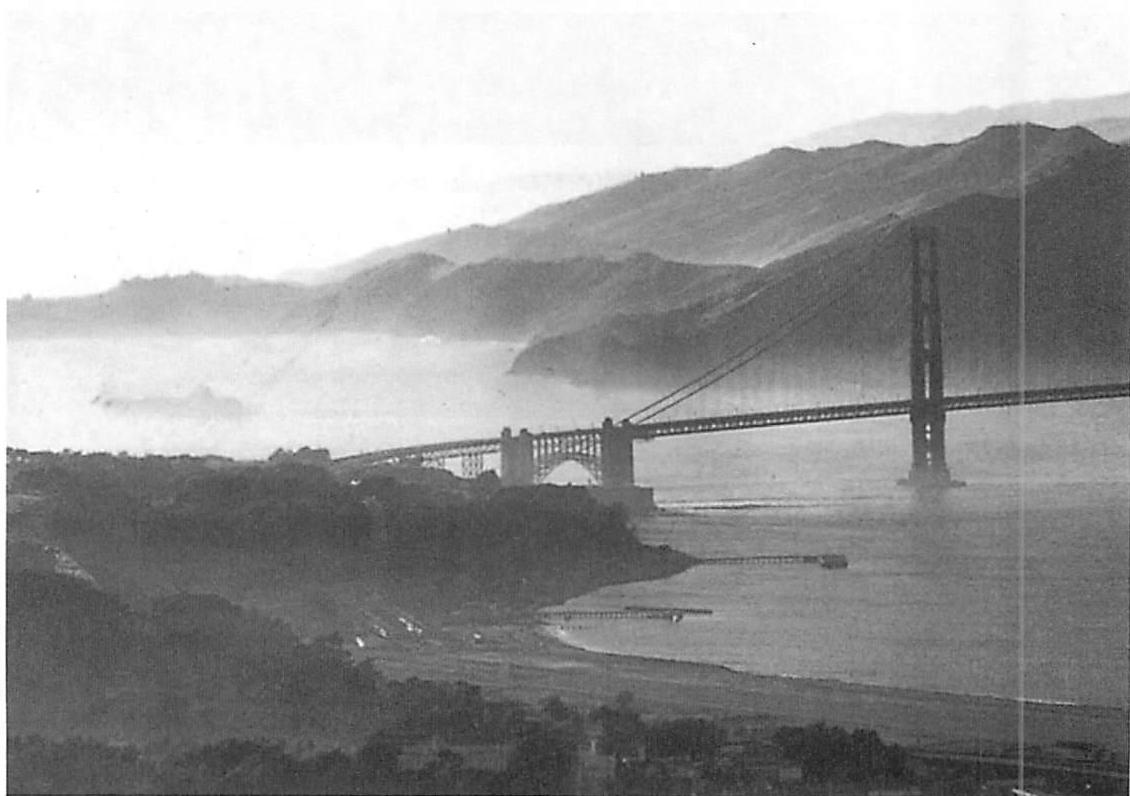

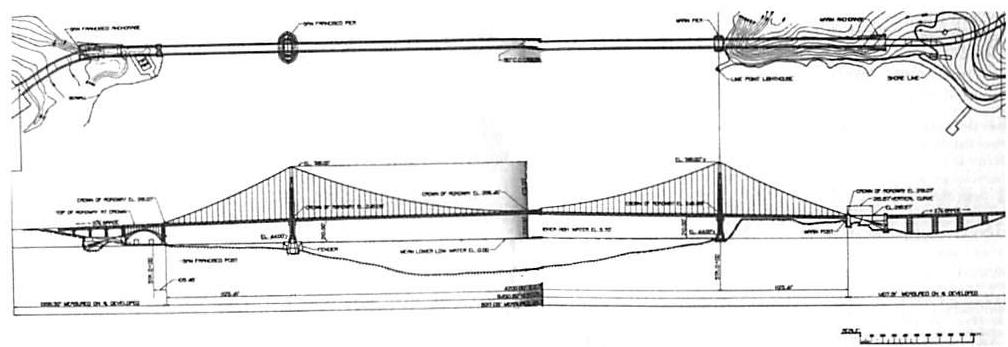

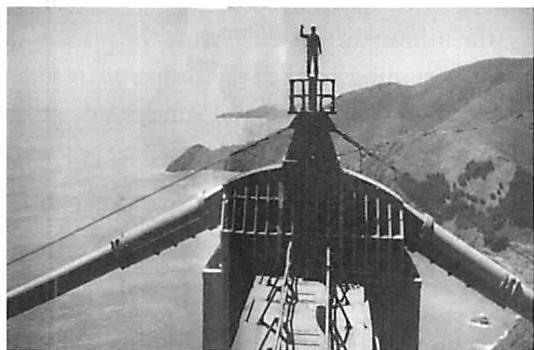

I remember a few years ago meeting an old man who told me he had put the last I-beam on the Empire State Building. He had also placed the highest steelwork on the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge. As he told me about the riveters and welders he used to work with, he described a kind of special ethic they carried with them: while doing their work, five hundred or a thousand feet above the ground, they were conscious, among themselves, that whatever they did — every rivet, every weld — was their responsibility and theirs alone. It was up to them to make a thing that was to last forever. It was in their hands, and there were no excuses.

This was vastly removed from the “I-am-just-doing-my-job” attitude which exists in the fragmented and mechanical process most often followed today, where the demarcation of responsibility is socially and legally drawn to make sure each person does not feel responsible for the whole.

I do not suggest that making should be reintroduced for reasons of nostalgia. But I shall prove that a process which is not based on making in a holistic sense, cannot create a living structure. And I shall demonstrate hypermodern processes, many using the most advanced techniques of the present and of the future, in which a new form of making dominates our attitude.

In every sphere of nature, and in every

sphere of human effort, there are trillions upon trillions of possible processes. Of these trillions, only a few are living processes — that is, actually capable of generating living structure. That does not mean that living processes are rare. There are, of course, still billions of them among the trillions. All the processes which generate nature — including what we understand as physics, chemistry, biology, geomorphology, hydrodynamics — they are all living processes, because they do virtually all generate living structure, at least most of the time. However, there is an even larger number of possible processes which fail to create living structure.

Since human beings are the first creatures on Earth who have managed to create non-living structure, the need to focus on non-living processes is new. Indeed, we have only even seen non-living structure and non-living process for the first time in relatively recent decades.

Traditional society almost never saw these non-living processes. Although traditional society was filled with human-created processes — human-inspired and human-invented — it was dominated by living process. Human beings in traditional societies, by and large, used living processes.

Non-living process is a recent arrival on the planet Earth. It is only in the modern era, and chiefly in the last 50-100 years, that human beings have given widespread use to processes of all kinds which are non-living, which therefore generate quantities of non-living structure.

However, since the distinction between living process and non-living process has now become visible, and since, for the time being, we have no precise conception or definition of living process, it has become urgent that we try to get one.

In this book I make an effort, perhaps for the first time, to make this distinction and to lay a basis for a theory — and for a form of daily practice — which allows for a world in which living process, hence living structure, dominates the world and its creation.

NOTES

Wholeness, defined structurally, is the interlocking, nested, overlapping system of centers that exists in every part of space. For definitions, see Book I, chapter 3, and Book I, appendix 2.

For a precise definition and analysis of living structure in buildings, see Book I, throughout, and especially chapters I, 2, 4, 5, 8 and II.

Also explained and argued in detail throughout Book I.

One of the few texts, and perhaps the first, to make a dramatically clear statement about the vital role of process in building was Halim Abdelhalim's THE BUILDING CEREMONY (doctoral thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1981). Another striking exception is the book by Stewart Brand, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: WHAT HAPPENS AFTER THEY ARE BUILT (New York: Viking, 1994), which clearly identifies the dynamic history of the building as one of its most salient features.

Richard Feynman, THEORY OF FUNDAMENTAL PROCESSES (New York: W. A. Benjamin, 1961).

D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, ON GROWTH AND FORM (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1917; reprinted volumes I and 2, 1959). Also Brian Goodwin, HOW THE LEOPARD CHANGED ITS SPOTS (New York: Simon and Schuster, Touchstone, 1994).

Ilya Prigogine, FROM BEING TO BECOMING (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1980), p. 3.

I am aware of one provocative counter-example, in the following passage by a philosopher, Bruno Pinchard: "It is on the subject of architecture that Aristotle achieves great precision in the presentation of his dynamics, when he analyzes the reality of the buildable as such and distinguishes it from the finished construction. Now the architecture is not only in the house that is built, but in the act of building itself. The mover in architecture is not only the mental image of the project in the architect's mind. Particularly for the great theorists of Vitruvian humanist architecture, who tried hard not to reduce the origins of architecture to the primitive hut, it is the architect's job to direct work on the site and so to transform the plan according to the necessities of the climate of the materials at his disposal. This amounts to drawing a distinction between the idea of the house and its form, its programming and the carrying out of the opus. In other words, the architect's final cause is not simple (the architect is not just a space technician), and it may be said that there is no classical architecture that does not carry in its realization the trace of the processes of its construction." From Bruno Pinchard, Appendix to René Thom's SEMIOPHYSICS, A SKETCH (Boston: Addison Wesley, 1990), pp. 237-38.

Bill McClung, my friend and editor, is a fire commissioner in the city of Berkeley and spends much of his life now making meadows in the Berkeley hills, converting fire-hazardous brush to something more alive and beautiful.

See, for example, Evans Pritchard and other early 20th-century functionalist discussions of social contracts.

See the preface to Book I. Our understanding of process, like our understanding of order, has been severely compromised by the value-neutral Cartesian picture, and in a similar fashion. In the case of static order at least, everyone knows that things have value; the mistake has been in the fact that we have been encouraged to think that the value of an object is subjective. Process presents a deeper problem since, in our time (with some exceptions), we are not used to evaluating it at all, even in subjective terms. We have yet to learn that, objectively, there is life-creating process and life-destroying process.

I start with an overview of a scientific question. Throughout the natural world, one sees myriad examples of systems which "come into being." Indeed, as we think about it, in natural systems there is nothing else but this "coming into being." Everything is coming into being, continuously.

Yet we have relatively little theory that allows us to grasp this process of coming into being. Although there have been many discussions in the last two decades about chaos, catastrophes, bifurcation, and emergence, about the generation of complexity from interaction of simple rules, about the processes that have become known as chaos theory, and the way that new structures emerge by differentiation and bifurcation, still, even now, there is not enough coherent scientific theory that tells us how these processes really work geometrically.

In the first four chapters I focus on the idea that a living process always has enormous respect for the state (and morphology and form) of what exists, and always finds a next step forward which preserves the structure of what exists, and develops and extends its latent structure as it creates change, or evolution, or development. This is the process which is "creative."

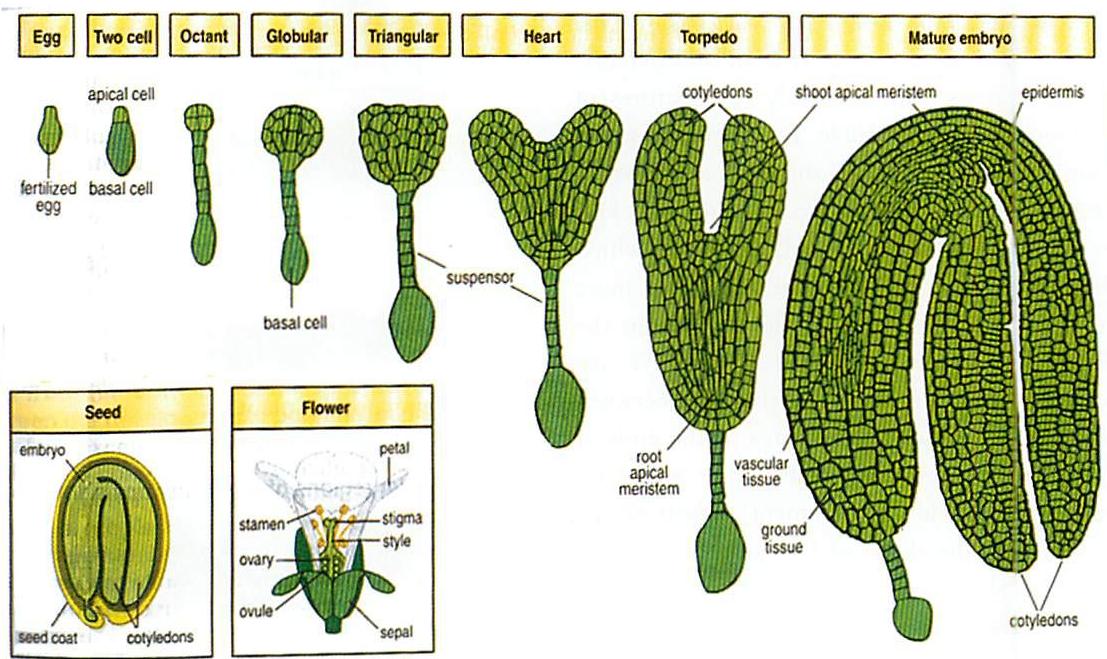

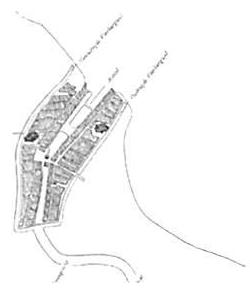

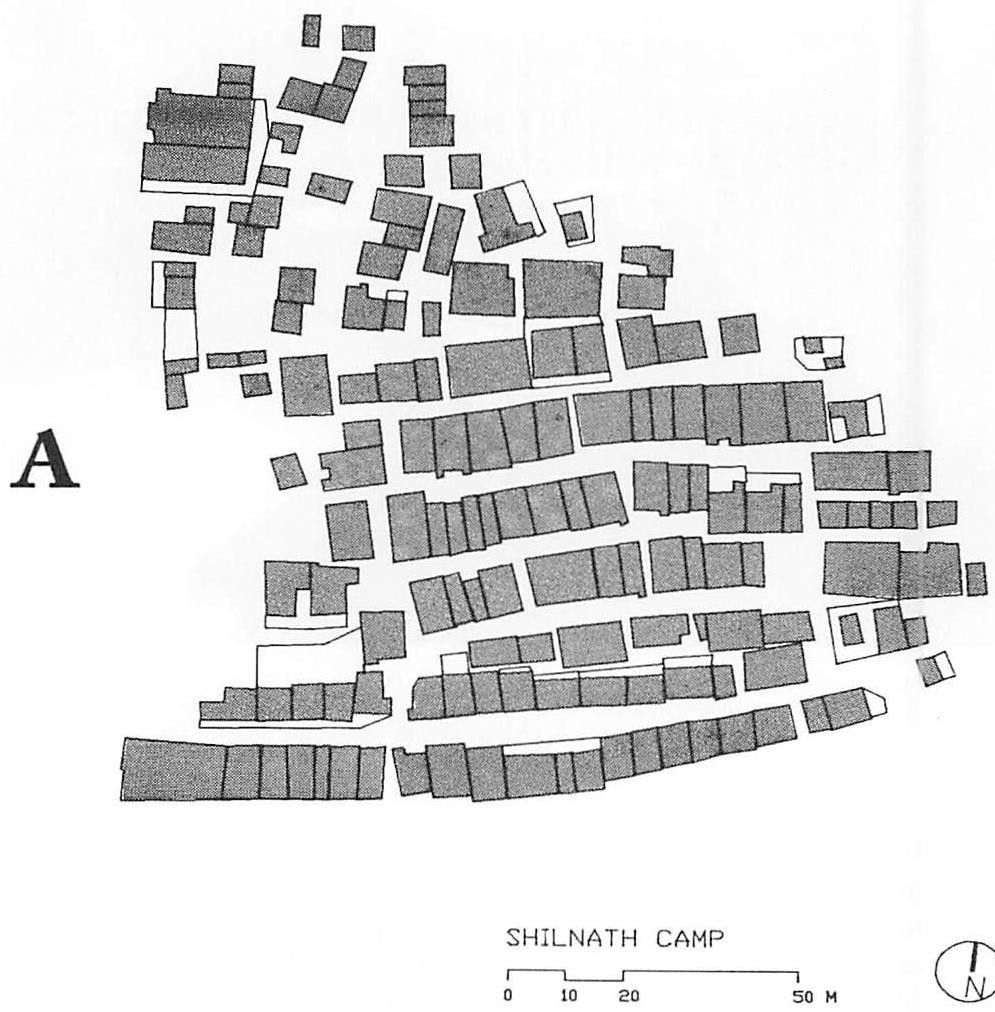

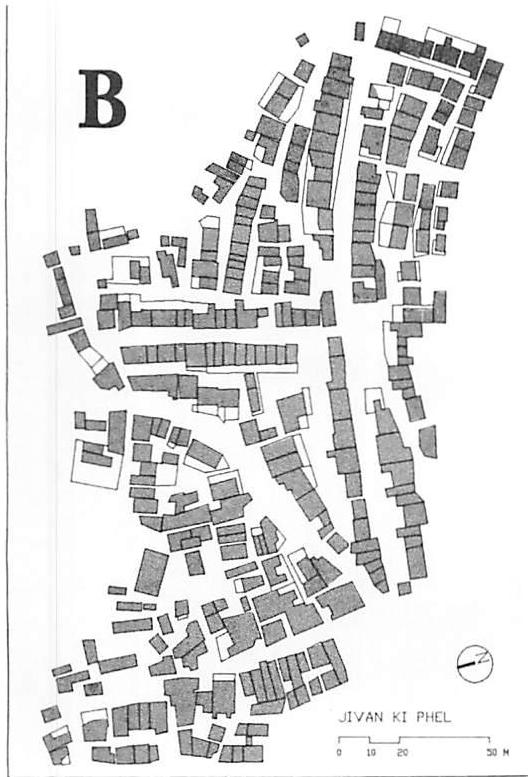

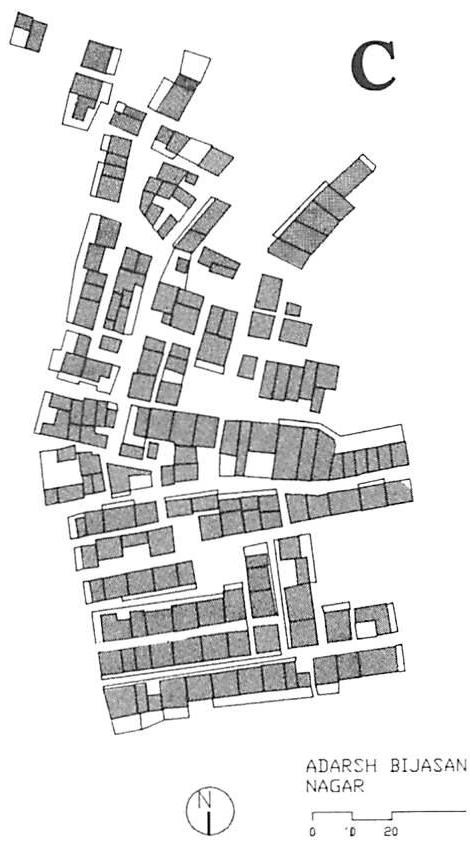

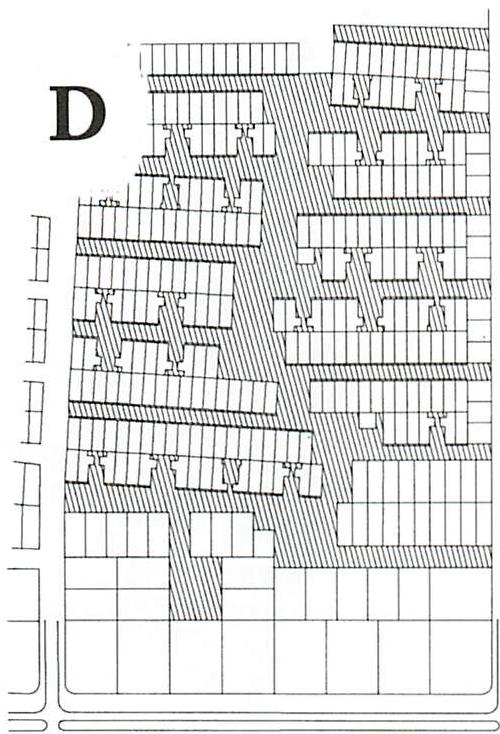

In chapters 1 and 2, I address these issues for cases in the natural world, and provide the outline of a tentative approach that helps us understand the unfolding of geometry in biology and physics. This theory provides the underpinning for what follows. In chapters 3 and 4, I turn my attention to the BUILT world, to towns and buildings and to the way the emergence of living structure in towns and buildings may be understood within the context of theory.

The searchlight on nature will show us that many of the processes we have come to accept as normal in architecture and city planning and development are, from a process point of view, deeply flawed. They are, as matters stand today, incapable in principle of generating living structure. For this reason the near absence of living structure in our built contemporary world cannot be a surprise to us. It follows, inevitably, from the flaws of the processes we have come to accept as a normal part of our society, and it will change only when the processes we use in our society, are changed.

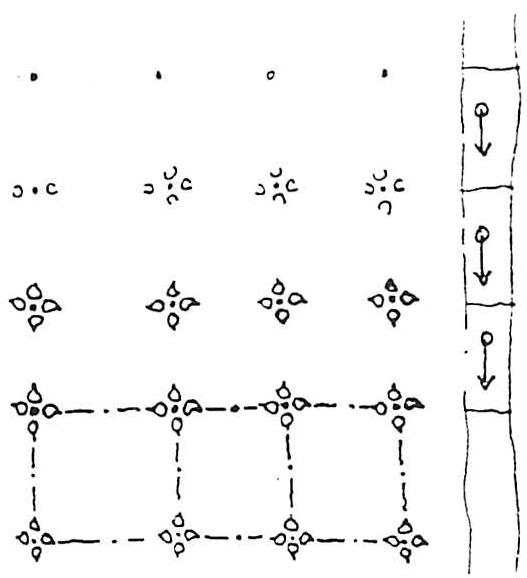

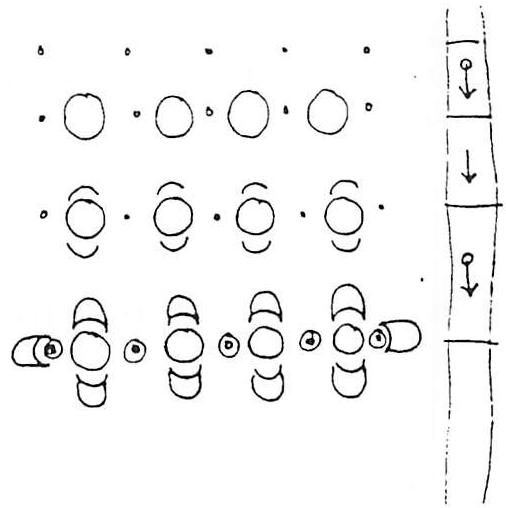

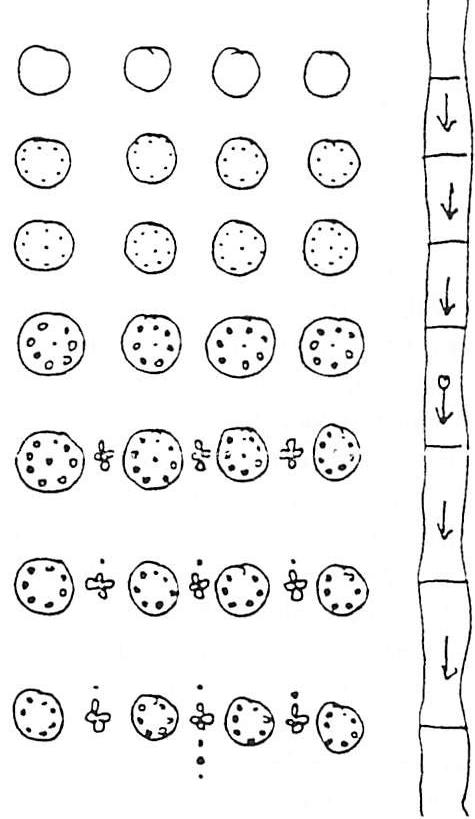

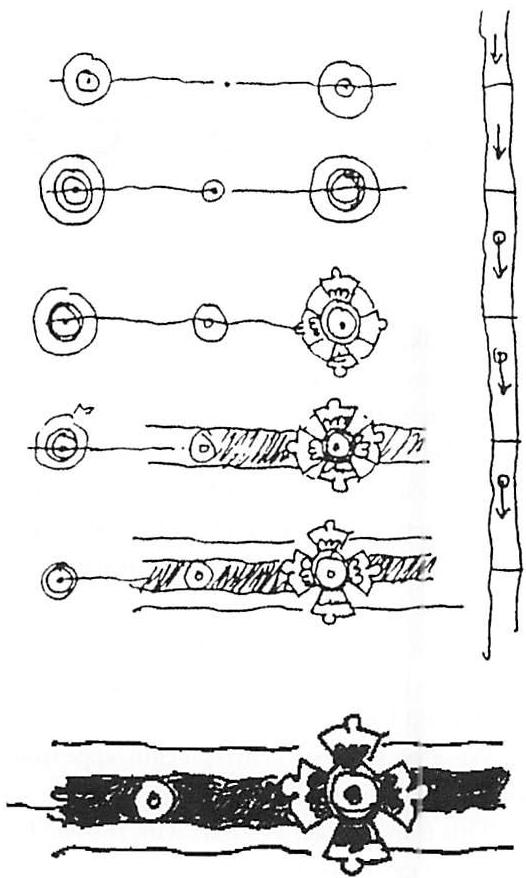

CHAPTER ONE: THE PRINCIPLE OF UNFOLDING WHOLENESS IN NATURE

1 / INTRODUCTION

How does nature create living structure?

Living structure, as I have defined it, is not merely the structure we find in living creatures — organisms and other ecological and biological systems. It is, in a more general sense, the character of all that we perceive as "nature." The living structure is the general morphological character which natural phenomena have in common.

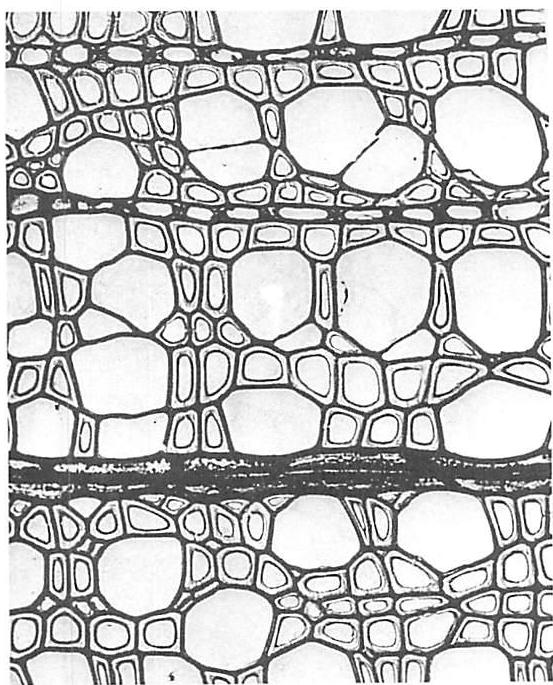

In Book I, I have tried to describe and characterize this living structure in very general terms. In the sense introduced in Book I, the living centers which appear in any given physical system have varying degrees of life. They have life because they are composed of other living centers that support and sustain and intensify each other. I remind the reader that in this way of thinking, living structure refers not to the biological systems in the world, but is a general character, appearing through all systems, organic and inorganic, of the natural world.

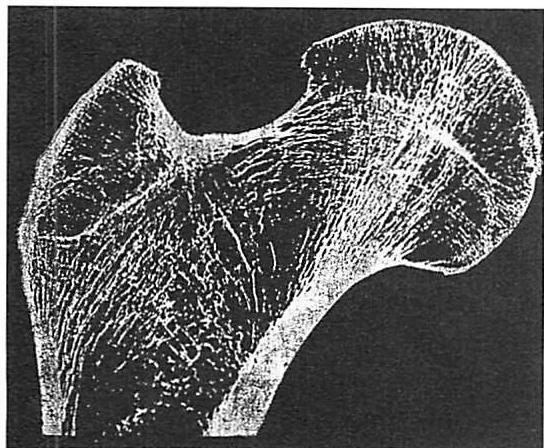

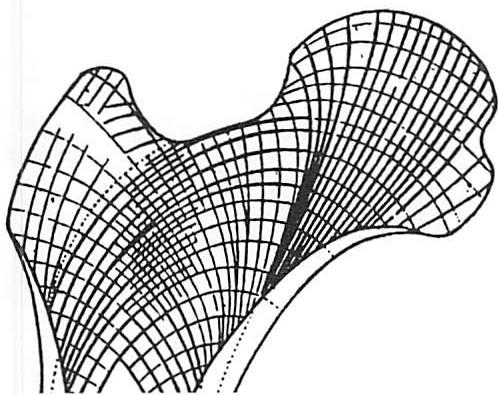

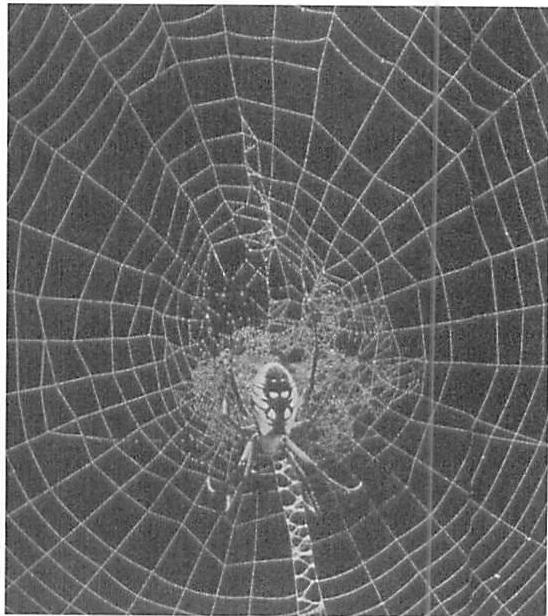

The way that centers manage to support and intensify each other in such living structure is chiefly governed by the repeated occurrence of fifteen geometric properties defined in Book I.¹ They are identified as: I. LEVELS OF SCALE, 2. STRONG CENTERS, 3. BOUNDARIES, 4. ALTERNATING REPETITION, 5. POSITIVE SPACE, 6. GOOD SHAPE, 7. LOCAL SYMMETRIES, 8. DEEP INTERLOCK AND AMBIGUITY, 9. CONTRAST, 10. GRADIENTS, 11. ROUGHNESS, 12. ECHOES, 13. THE VOID, 14. SIMPLICITY AND INNER CALM, 15. NOT-SEPARATENESS.

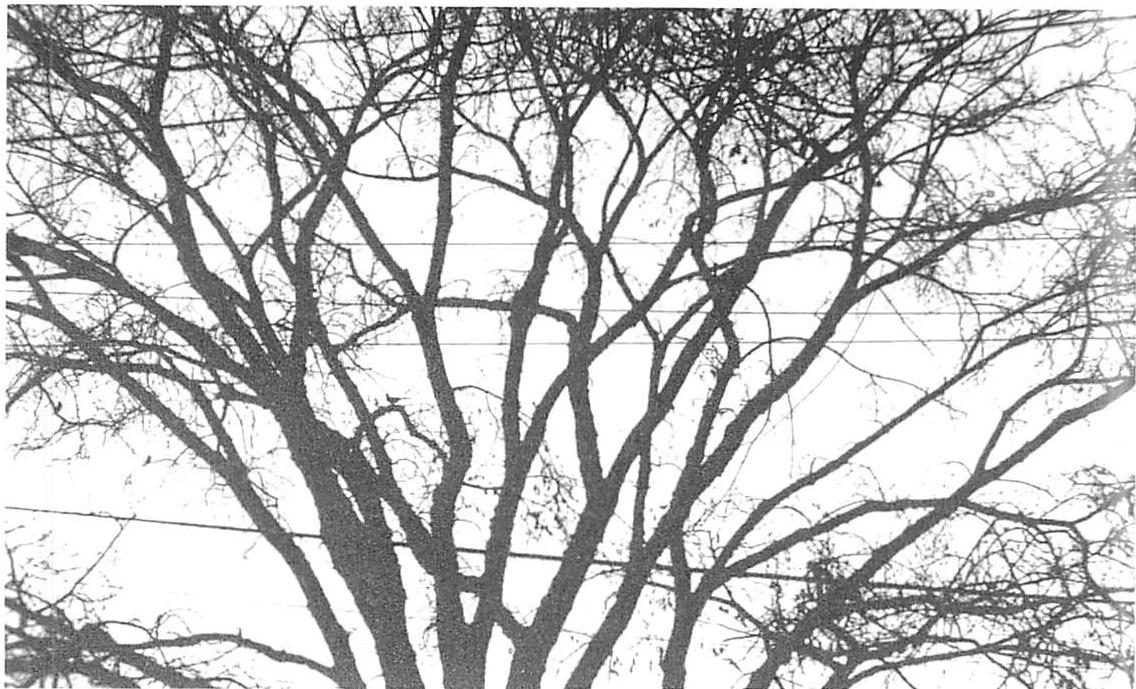

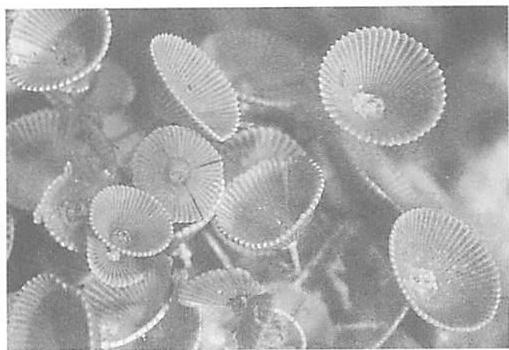

What I call the living structure of nature — that which we see in the natural world around us — is also largely governed by these fifteen properties and their interaction and superposition. Chapter 6 of Book I contains many examples that show the field of centers and its associated fifteen properties in rocks, animals, plants, clouds, rivers, landscapes, crystals. Again and

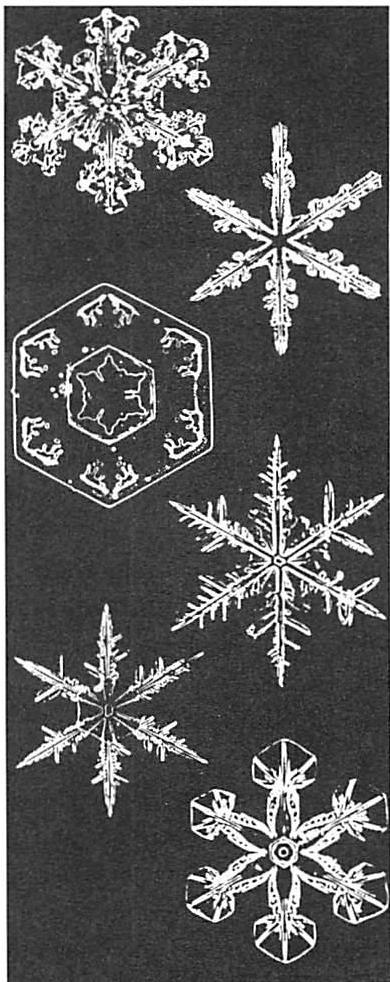

again, throughout the worlds studied in physics, chemistry, biology, geology, fluid dynamics, ecology, crystallography, cytology, and molecular biology, we find densely packed structures of centers in which thousands of centers support each other.² Thus nature creates living structure every day, in sand, in rivers, in clouds, in birds, in running antelopes. It does it, both in the organic and inorganic realms, apparently without effort.

But why does living structure, with its multiplicity of centers and their associated fifteen properties, keep making its appearance in the natural world? Why, and how, does living structure keep recurring in these widely different domains? What is the mechanics of the process by which living structure is made to appear, so easily, in nature? What is the process by which this kind of structure repeatedly, and persistently, occurs?

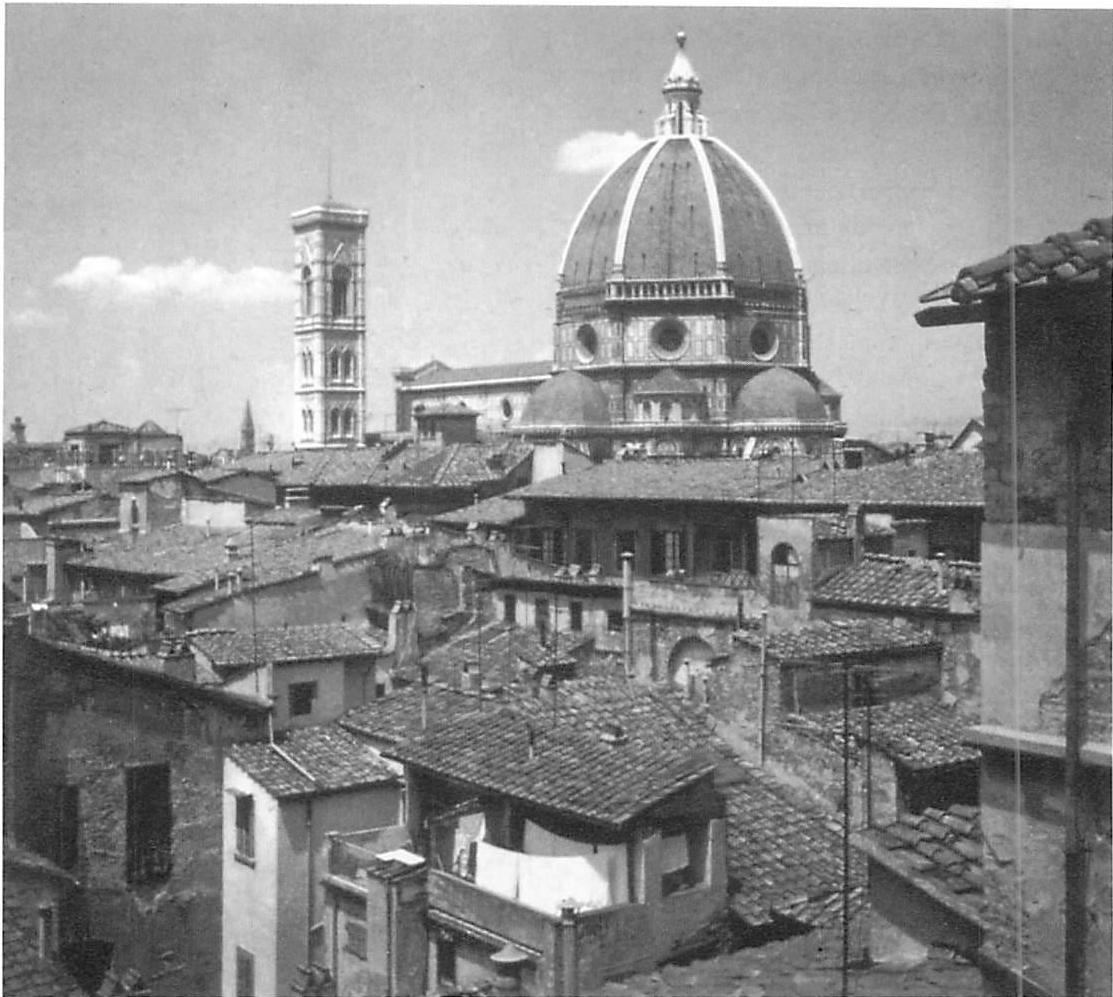

Oddly enough, the persistent appearance of living structure in nature is not easy to explain. That is why, in this book about architecture, I start by trying to understand nature in a new way. Once we have that understanding, we may have a basis for thinking about architectural process and for identifying processes which are capable of creating a living world in the realm of architecture. In a good building, as in nature, there is also living structure. Each living center contains thousands of living centers; and the centers support each other in an intricate pattern. But as we see from the many 20th-century buildings which lack this structure, there is — at least in modern society — some kind of immense practical difficulty in creating such a living structure in the real world of buildings. Indeed, the very large number of recently built buildings which lack living structure suggests that for some reason it is especially hard for us in our present period of history.

Yet nature manages the task rather easily. That is why I say, “To learn how to create living structure in buildings, we had better start by looking at nature.”

2 / NOTE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC READER

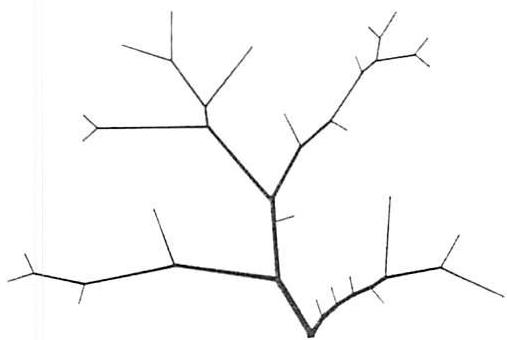

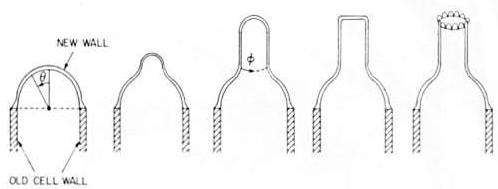

In what follows, I shall argue that the emergence of new structure in nature, is brought about, always, by a sequence of transformations which act on the whole, and in which each step emerges as a discernible and continuous result from the immediately preceding whole.

This thought, obvious if taken naively, but profound and difficult if taken literally as a piece of science, relies entirely on the possibility that we can form a coherent and well-defined idea of what is meant by “the whole,” and of what is meant by a structure which grows from the whole, and preserves the wholeness while it is moving forward. Such a thought is well-nigh impossible today, because in spite of the uses provided by David Bohm of the word “wholeness,” there is in science today no concise or well-defined idea of wholeness as a structure. Yet without a well-defined idea of the whole, the thought I have expressed here cannot be completed or used. The nub of the point which governs the thinking of this book, is that we are able to approach clear thinking about this issue, and have enough of a well-defined formulation of what wholeness “is” to see the outline of a new theory built on this foundation.

Although I cannot claim to have fully solved the problem, I believe that in Book 1, I have given a sufficient description and definition of “the wholeness” so that it may be understood as a well-defined structure which occurs in all configurations.

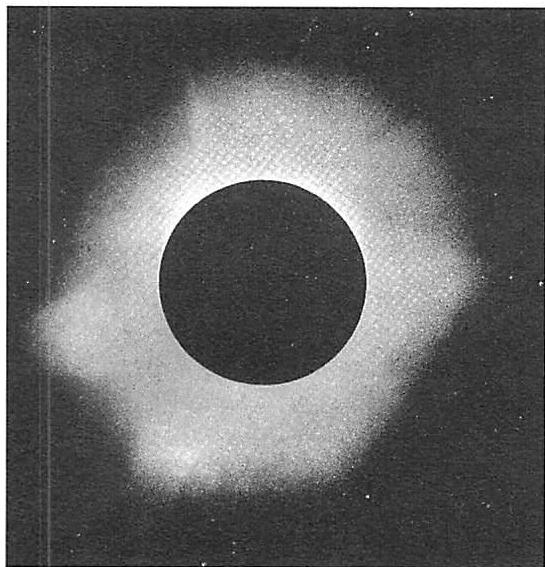

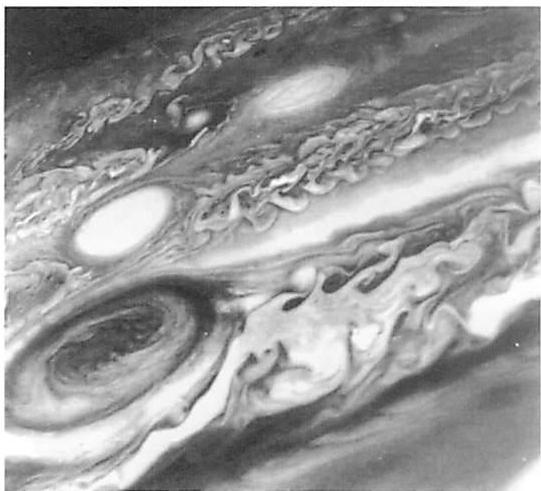

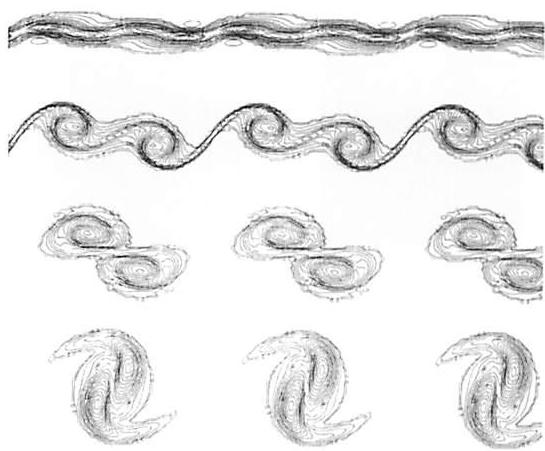

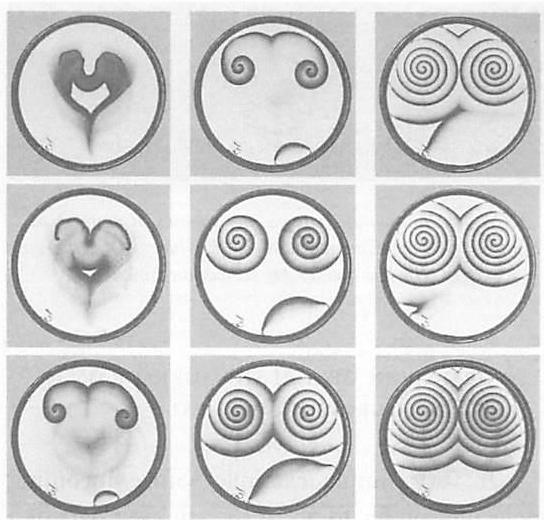

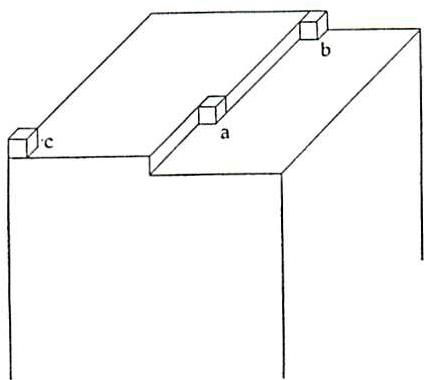

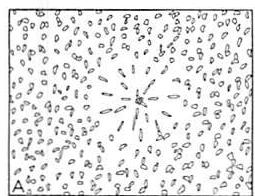

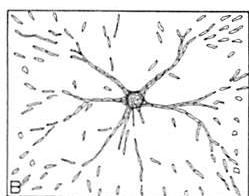

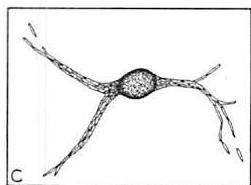

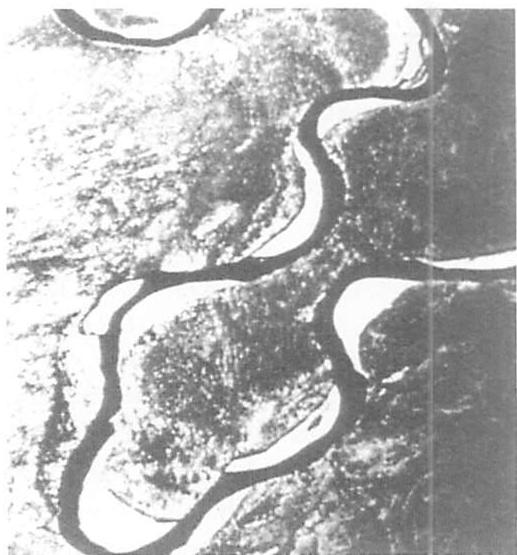

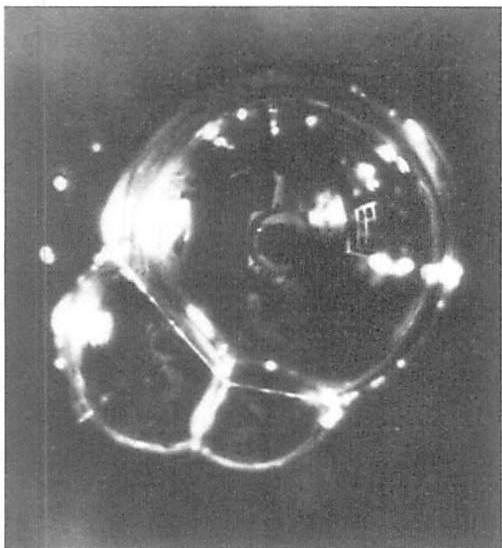

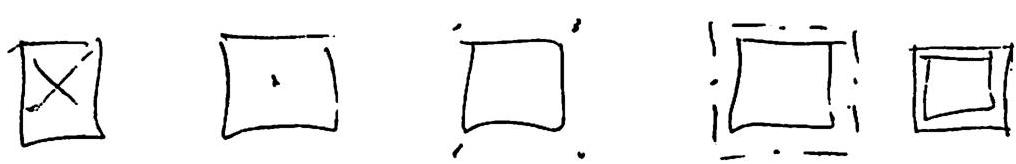

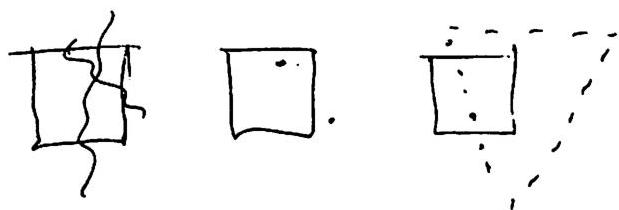

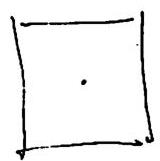

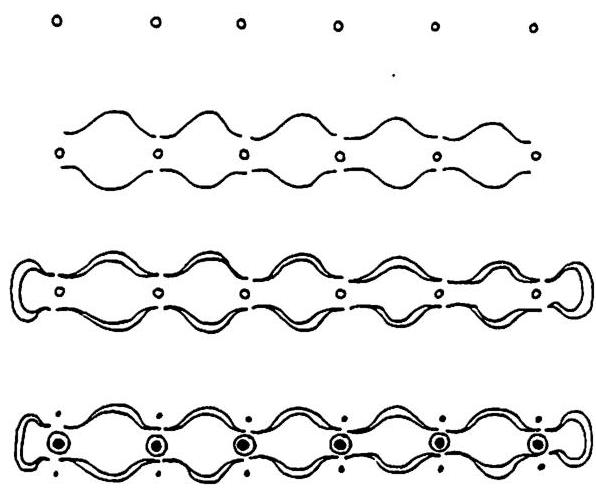

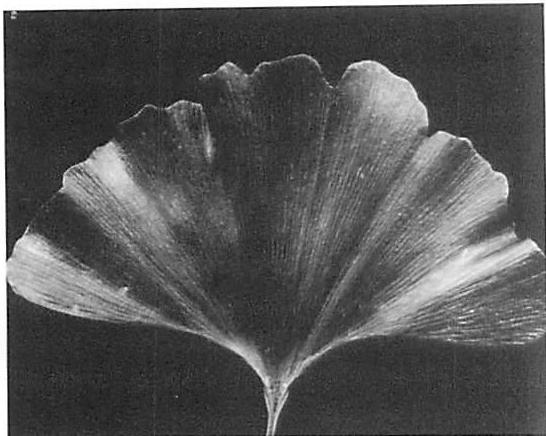

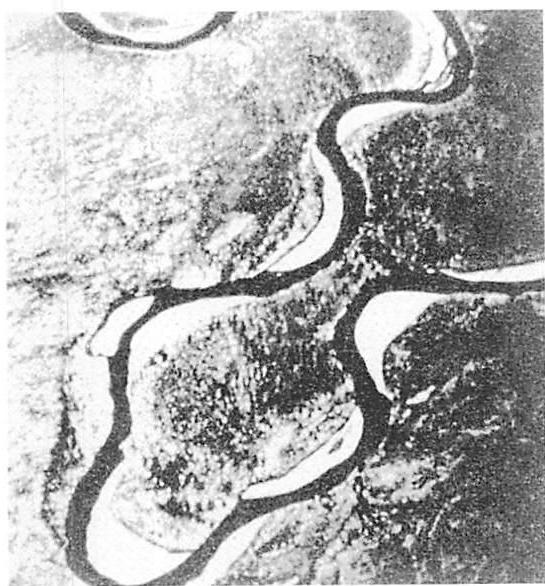

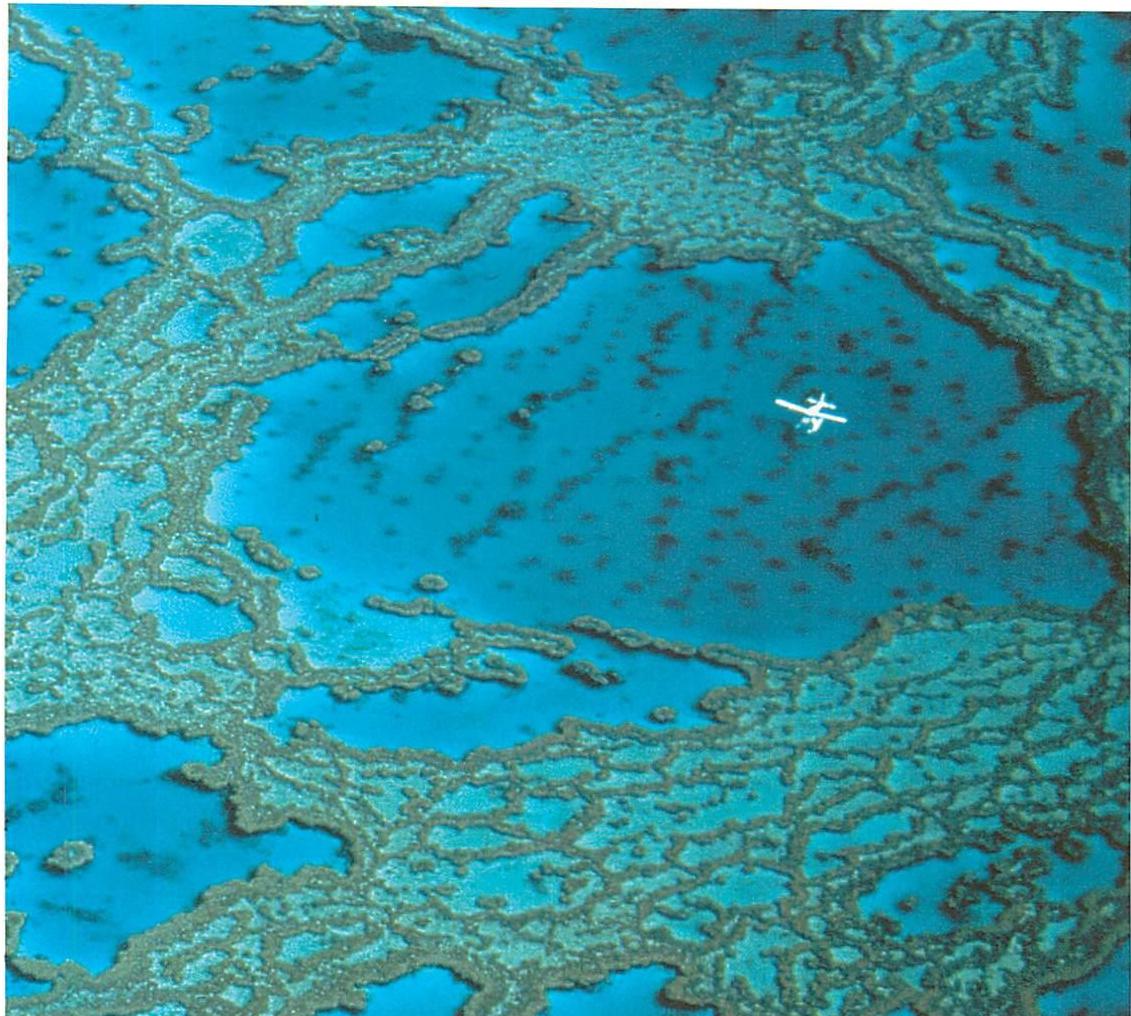

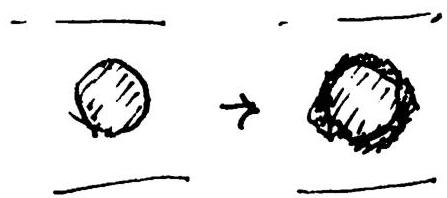

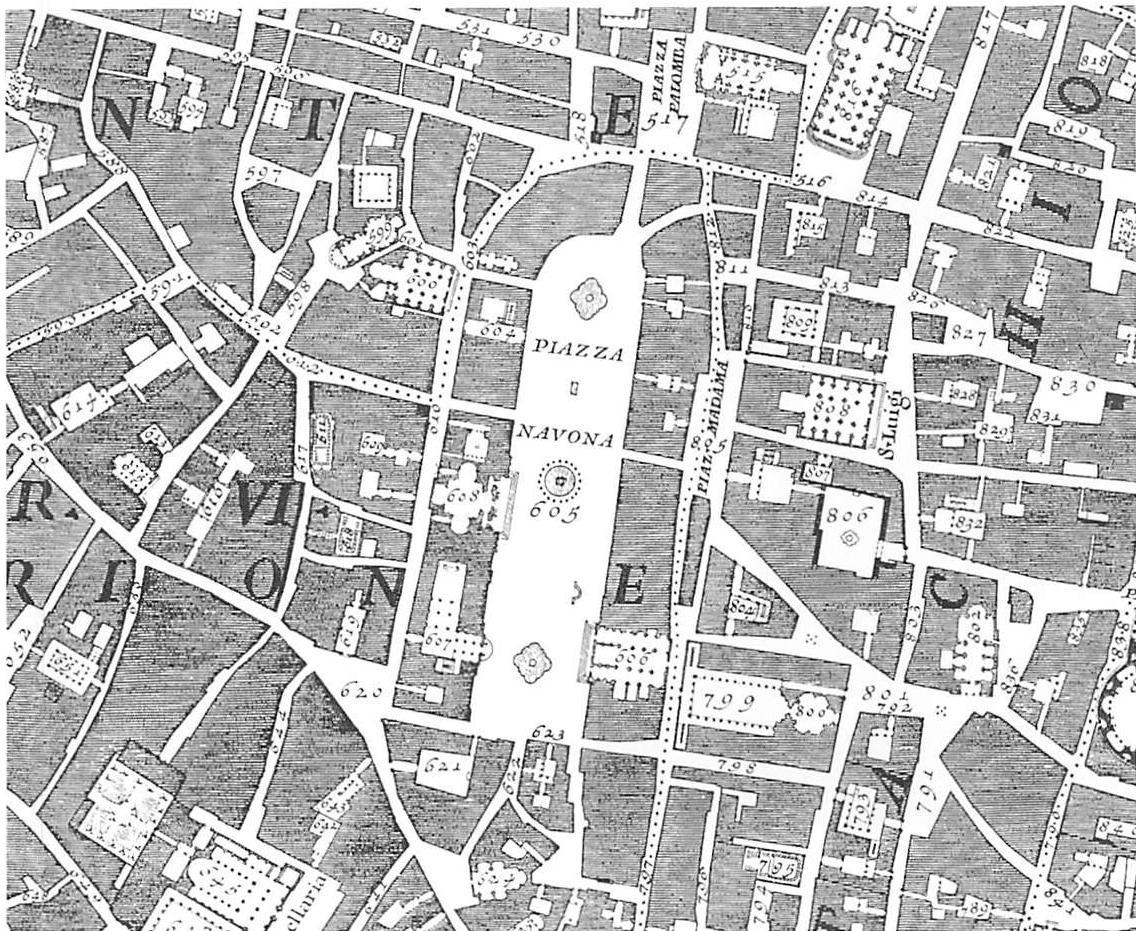

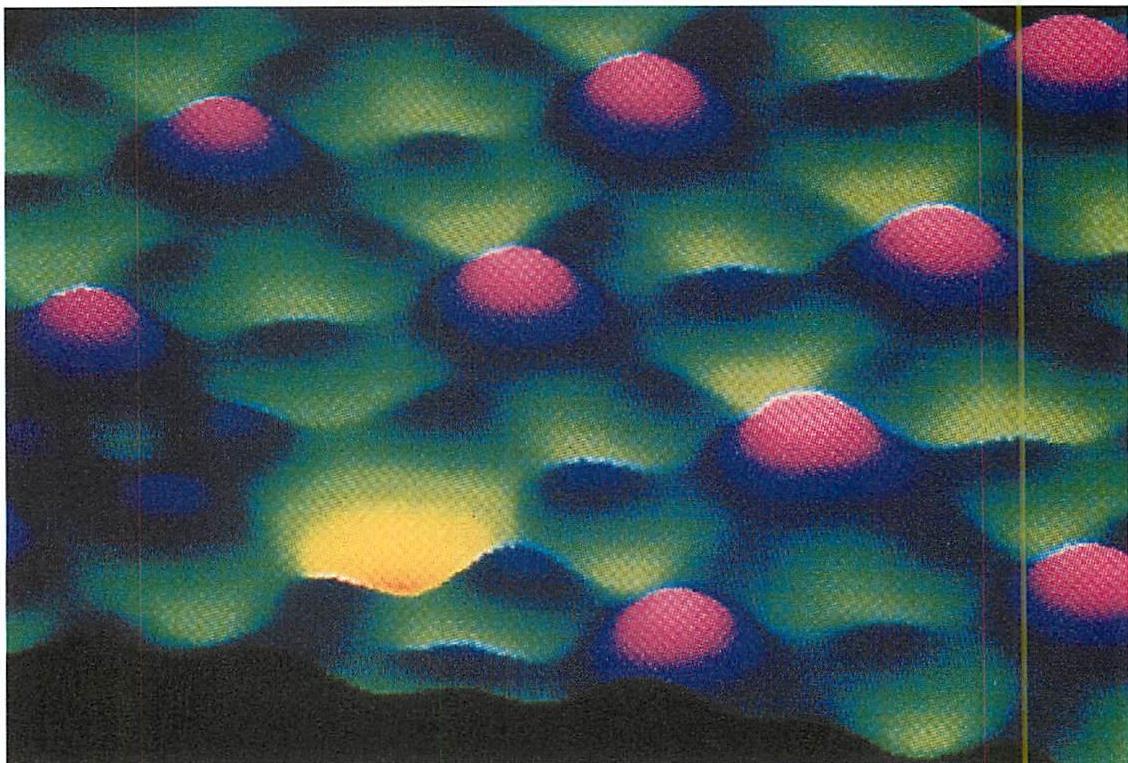

Briefly, recapitulating passages of Book 1, the wholeness is what we think of as the “gestalt,” the broad gestural sweep of a figure, or of a configuration. In the Belousov reaction (images shown on page 27 below), it is the “curly-Y” figure — the lily-shaped figure — which has two halves sweeping away from each other, and containing between them a V-shaped center. That is what exists in picture 2, and what exists, already, in an earlier form, in picture 1. The 2nd stage has emerged from this wholeness, and has preserved it, even as it introduces other structure. In the stages 2 and 3, we see another gestalt, which emerged from the first — a pair of round whorls or spirals — partly present in the picture 2, and fully developed in picture 3. As we go from picture to picture, or from stage to stage of the reaction, we see a continuous series of such configurations, in which the deep gestalt of each stage forms, grows, swells, develops, and gives rise to a new configuration.

It is this process, which I mean by “emergence of the wholeness” and by “emergence of the configuration from the wholeness.”

What I have said, in Book 1, is that this wholeness is in principle amenable to mathematical treatment and description. A wholeness consists of a recursively nested system of centers, all more or less living ones (according to the definitions of Book 1). It displays the fifteen properties, and in a sense one might say that the fifteen properties are the primitive configurations from which all wholeness is built. In more detail still, considering the arguments and examples of Book 1, appendix 3, the wholeness may always be viewed as a nested system of local symmetries, and it is the configuration of the system of nested local symmetries which gives us the character of any particular wholeness, in any particular configuration.

I claim that even in continuous phenomena (such as curves, curved surfaces, organic forms in three dimensions such as leaves or organs, or in configurations of subtle gestalt such as gradi-

ents and smoothly meandering curves) it is always the wholeness, as defined here, in terms of the strong centers which appear, and in terms of local symmetries, which provide the handle of this wholeness.

What I call the wholeness is, to a very rough degree, a mathematical representation of the overall gestalt which we perceive, or which we are aware, which gives the character to the configuration, and which forms, what an artist might call, his most intuitive apperception of the whole.

Now, in simple outline, what I claim in this chapter, and in many succeeding chapters, is that natural process—and all living processes—come about as a result of sequence of transformations which emerge from, and act upon, this wholeness—bearing in mind that the wholeness is a well-defined thing, not an artistic

thing—and that it is indeed from this wholeness, not previously identified in science with precision, that all growth and morphology emerge.

And yet I must apologize. Although I have given a nearly adequate definition of what this means, I have not given precise enough treatment, yet, to provide a strict mathematical treatment. What follows then, should be understood as proto-mathematics, where a structural idea, mathematical in principle, is available, and may guide our thought—but the hard work of formulating a mathematics with which one can calculate, has only just begun.

With this shortcoming in mind, please regard the following discussion, and presentation of examples, with some forgiveness. I have come as close to being accurate as, at present, I know how.

3 / THE NEED FOR A GENERAL EXPLANATION OF THE WAY THAT LIVING STRUCTURE IS CREATED

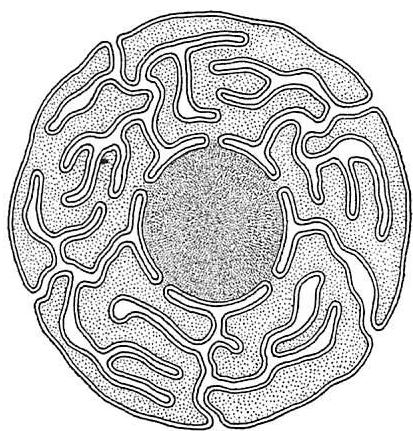

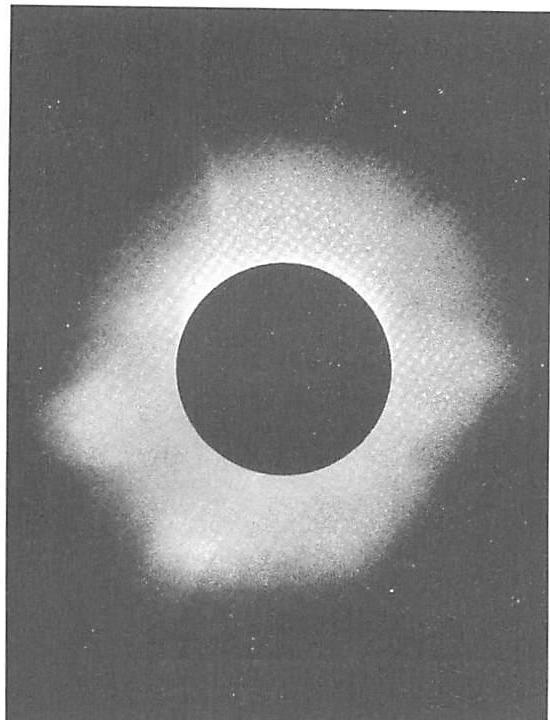

When we look at nature, we can nearly always find an explanation for any one of the fifteen properties as it appears in any one particular instance. Take BOUNDARIES, for example. Conventional plasma physics can be used to explain the appearance of the plasma boundary layer that forms around the sun. Hydrodynamics can be used to explain the silting up of the mouth of a river like the Rio Negro, where it flows into the Amazon, to form a pattern of streams bounded by great swaths of silted mud deposited by stream flow. Biological studies suggest why a cell is constructed to have a thick boundary layer, larger in volume than the nucleus of the cell. It is needed as the zone where chemical exchanges happen.

But it is quite another matter to give a general explanation which tells us why massive and substantial boundaries will, in general, tend to occur again and again, throughout nature, within three-

dimensional systems. This question involves a level of morphological thinking which has no familiar language in contemporary mathematics.

I have argued in Book I that the fifteen properties are necessarily associated with living centers and are the ways in which centers appear in the world, come to life, and cooperate to form other living centers. But that, in itself, does not explain why they keep appearing. We need a more systematic, general explanation. It is extremely hard to formulate a general rule for any one of the fifteen properties which gives us a convincing explanation as to why that property appears again and again and again throughout nature.

This issue is far from trivial. Although recent developments in complexity theory have shown how linked systems of variables, under the right conditions, will cooperate to form emergent order, that in itself does not yet tell us why the particular kind of order formation I have

identified as living structure, keeps on recurring, time after time.³

Yet there does, in an enormous number of empirical cases, appear to be a process which produces centers — and above all “living centers” —

packed with density of other centers and hence with life. Why do these living centers appear? Why does living structure appear in the world? What is it — in the detailed history of natural systems, with its mechanical causation — that can, step by

step, keep on making the fifteen properties appear in general, and that therefore, in general, causes the repeated creation of living structure in the inorganic and organic world?⁴

4 / CREATION OF STRUCTURE AS IT OCCURS IN NATURE

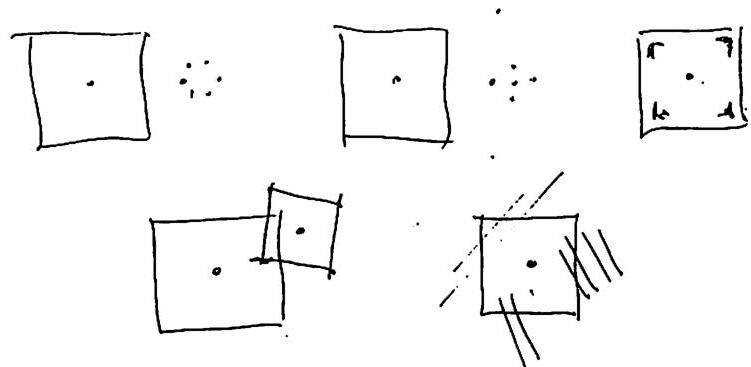

In what follows, I invite the reader to look at examples, while considering the existence of a fundamental principle which I call the principle of unfolding wholeness. This principle states that, in the evolution of an otherwise undisturbed system, the wholeness $W$ is progressively enhanced and intensified. This wholeness, as defined in chapter 3 of Book I, is the system of strong centers which occurs in space.⁵

According to this principle, the transformations which occur in the system take whatever wholeness exists at any given instant and continue it and intensify it while, broadly, maintaining its global structure, so that at the next instant that wholeness is more pronounced; as time goes forward, the wholeness gets progressively intensified, step by step by step. It is this process—I maintain—which is responsible for the creation of living structure. When the wholeness is intensified again and again, precisely that structure we recognize as living (with its fifteen properties) will begin to appear. In this view, then, the appearance of living structure in the world is caused by the repeated application of the principle of unfolding wholeness to every system.

I believe the principle of unfolding wholeness is consistent with most present-day physics and biology. It is also consistent with recent thinking in non-linear dynamics, catastrophe theory, and bifurcation theory.⁶ It is, however, a principle which is not automatically given by anything currently identified in these disciplines. As such, it is a new principle, necessary, I believe, in order to explain the appearance of living structure in the world.

If we examine the wide variety of cases from nature which I present in the next few pages, we shall see that they all show a particular kind of structure-preserving, smooth unfolding. That is true, even when systems pass through bifurcations and catastrophes. In each case, there is a path of development that is notable for being smoothly structure-preserving in a way that keeps the global structure intact. In the terms I have defined in Book I, it is wholeness which exhibits smooth unfolding.⁷ That is, the structure I have defined as the wholeness, as it changes from state to state over time, follows a path where the centers which constitute the wholeness (and particularly the large ones) are changing as little as possible. The wholeness is essentially preserved at each step, and the new structure is introduced in such a way that it maintains and extends—but almost never violates—the existing structure. It is globally structure-preserving. That is why the unfolding seems smooth.

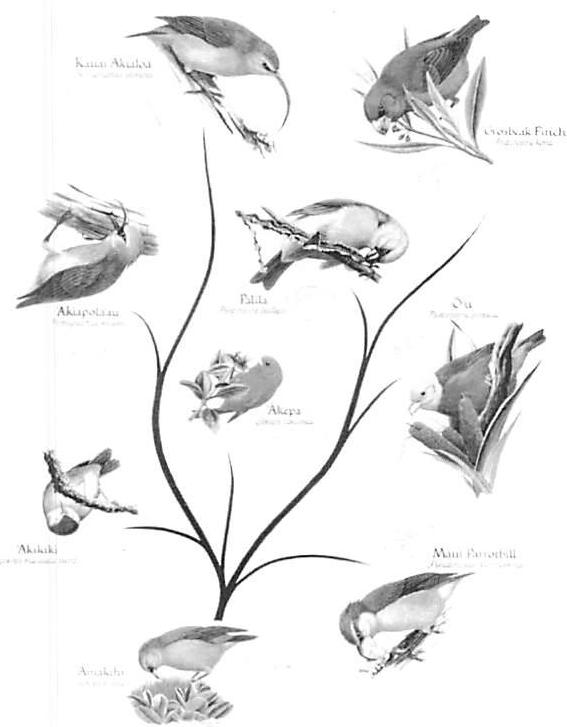

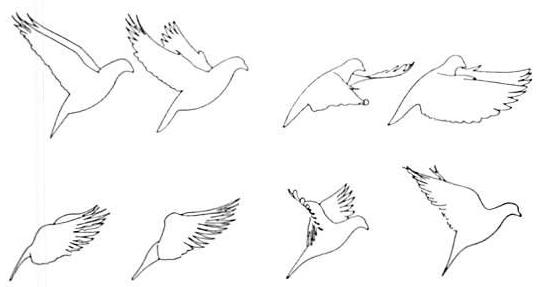

In the following pages I illustrate sequences for such processes in the following cases:

Formation of a spiral galaxy.

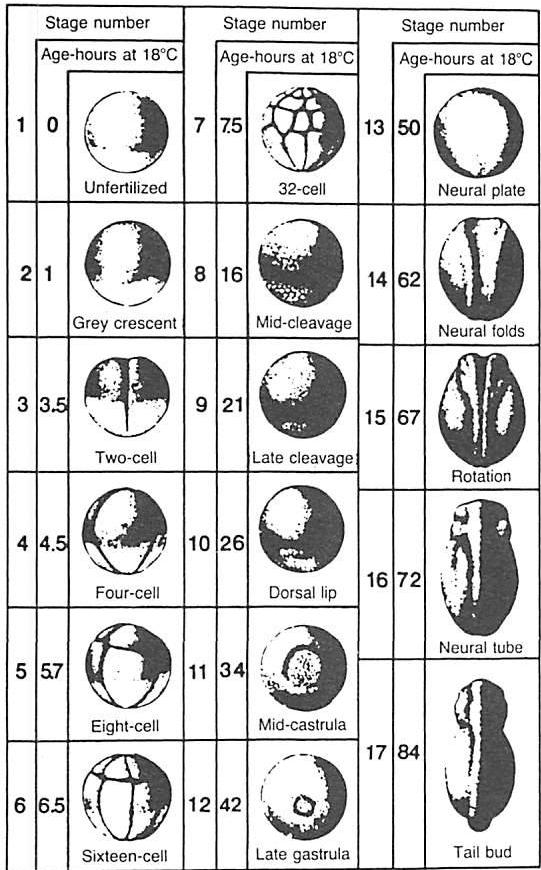

The formation of a frog embryo.

A breaking wave in the ocean.

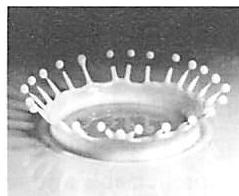

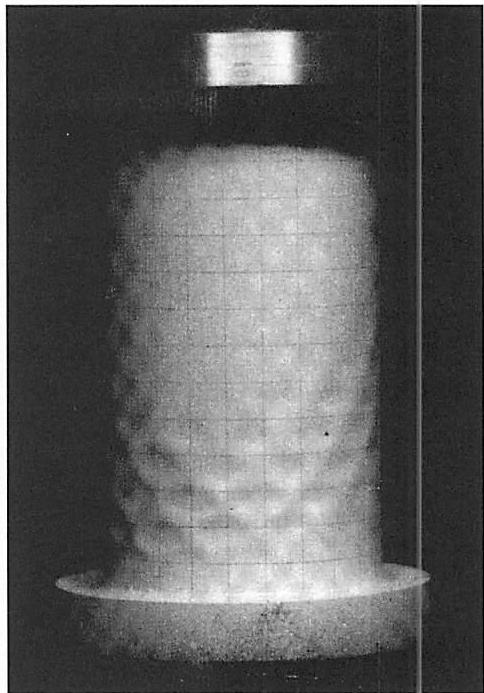

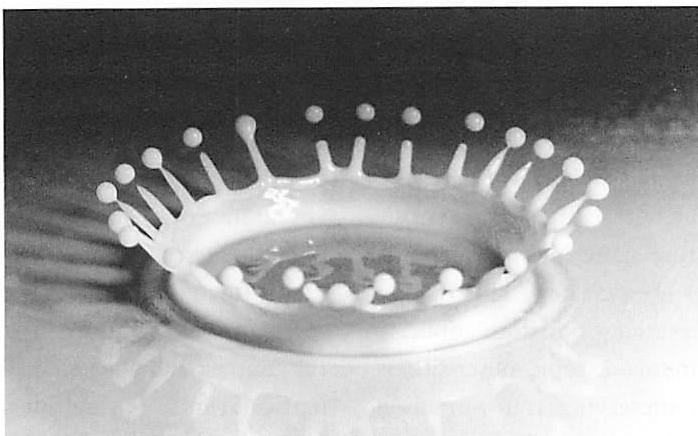

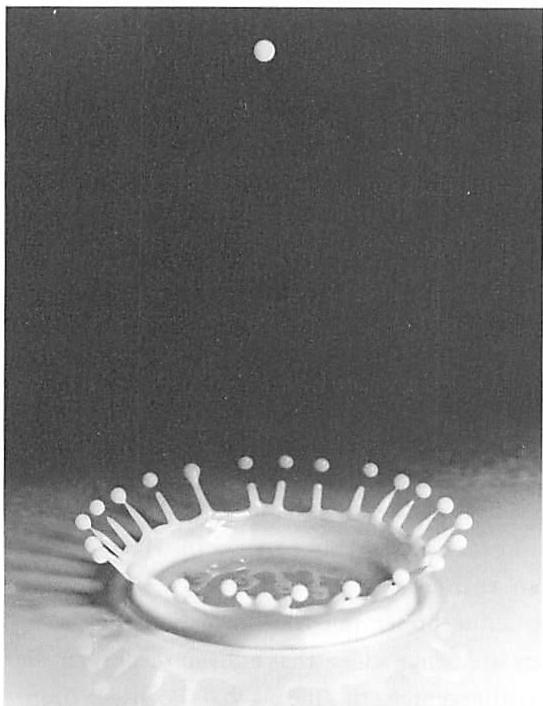

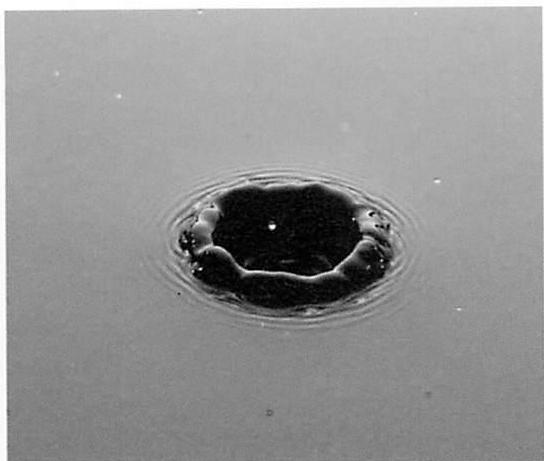

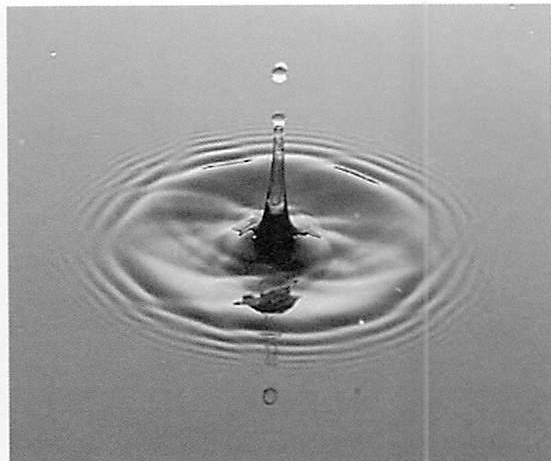

Formation of a milk-drop splash.

Formation of vortices on the surface of Jupiter.

Evolution of different beaks in subspecies of

Hawaiian finches.

Flight of a pigeon.

The sequence of the Belousov-Zhabotinski

reaction.

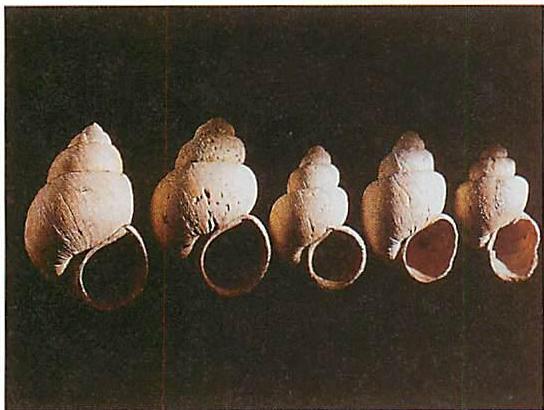

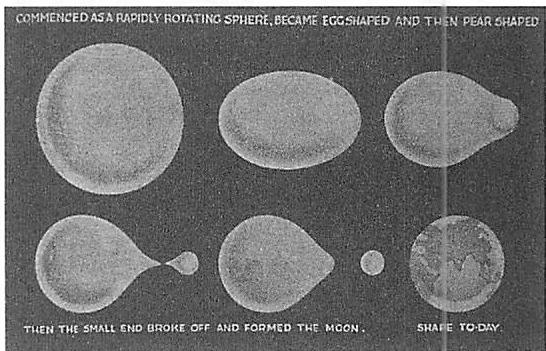

Evolution of mollusks.

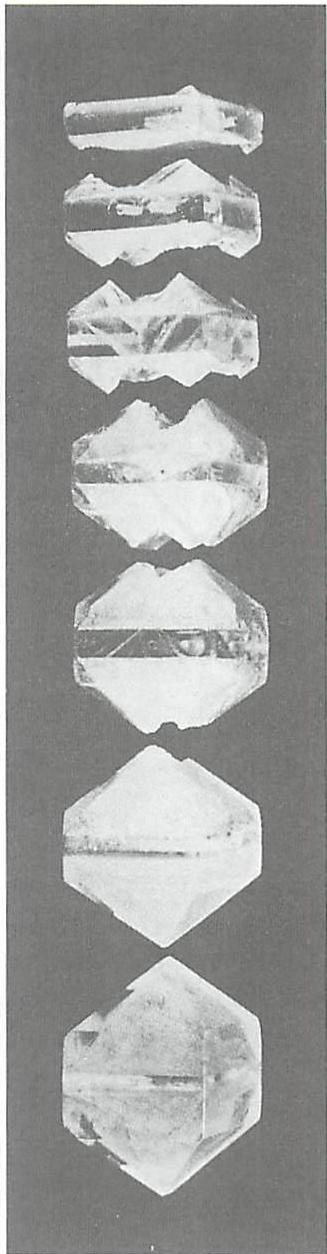

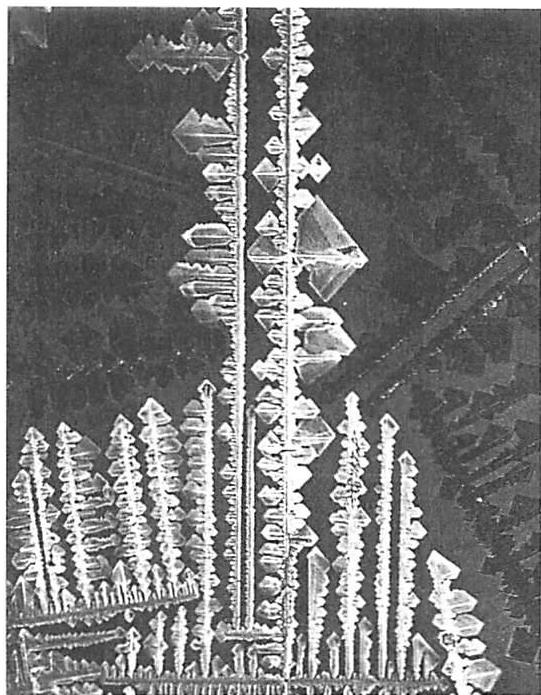

Formation of a plane surface on a growing

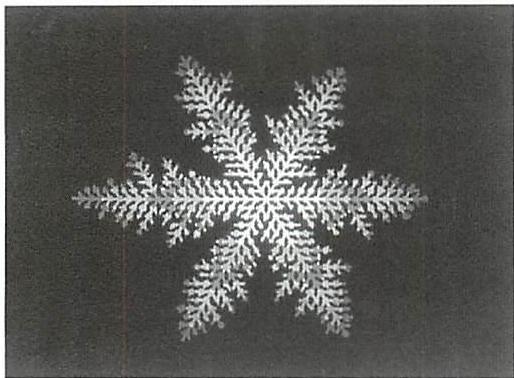

crystal.

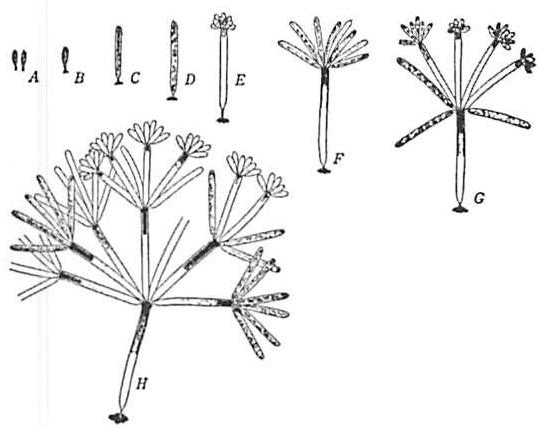

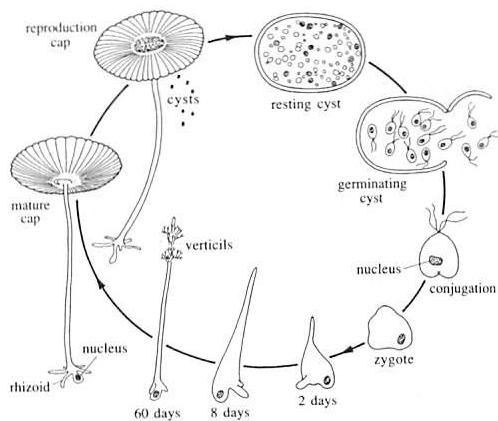

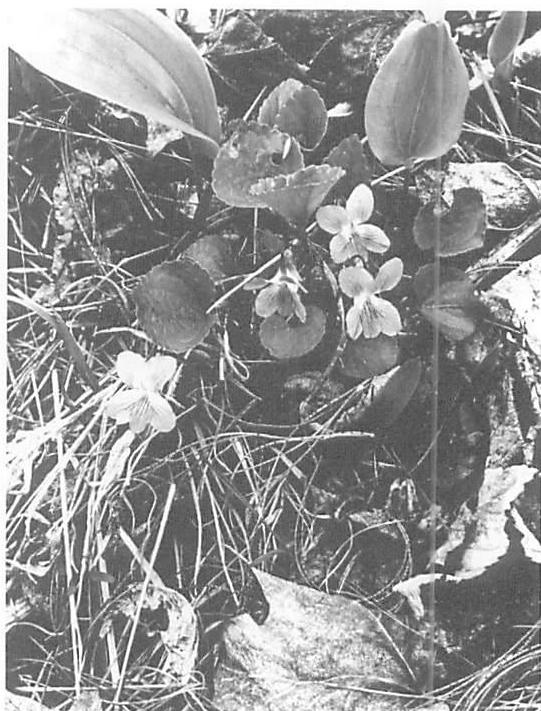

Development of algae.

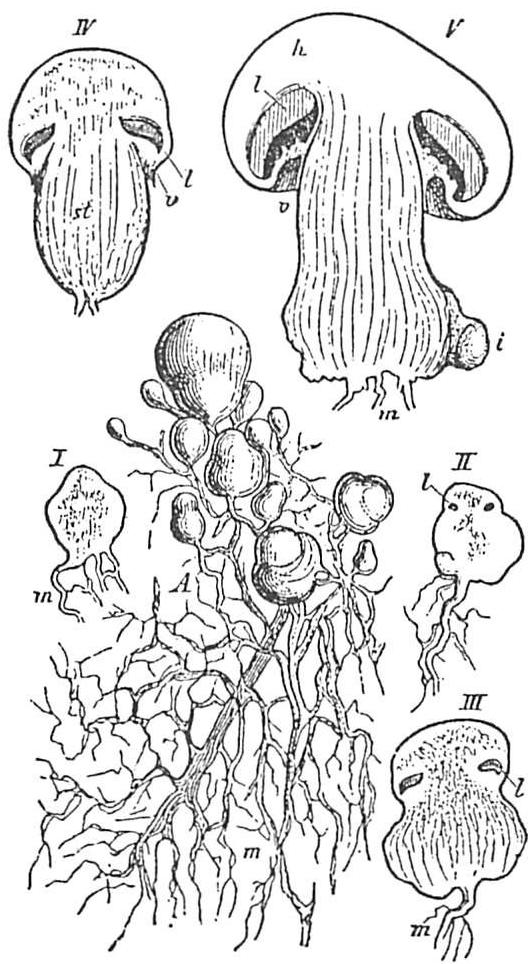

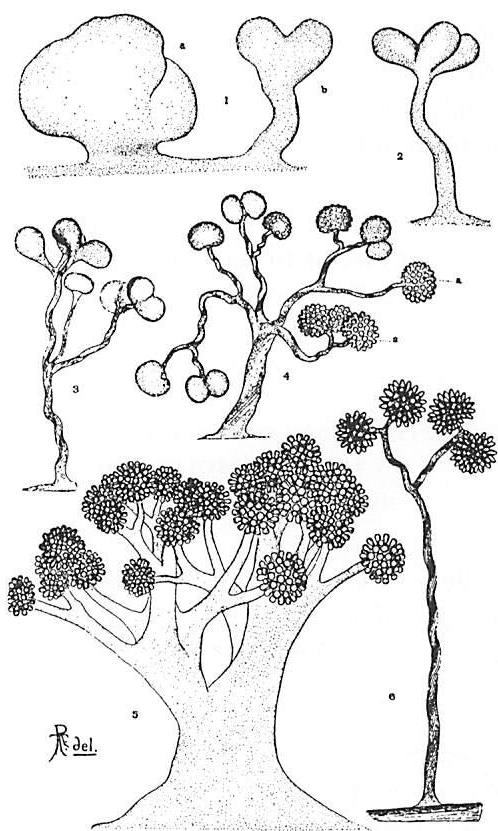

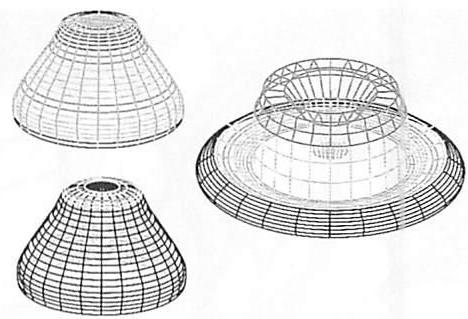

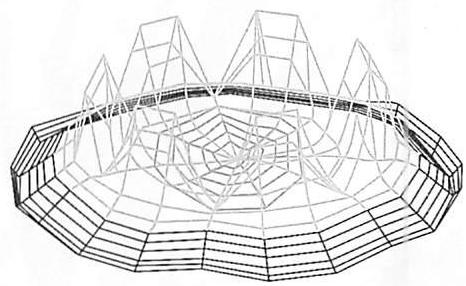

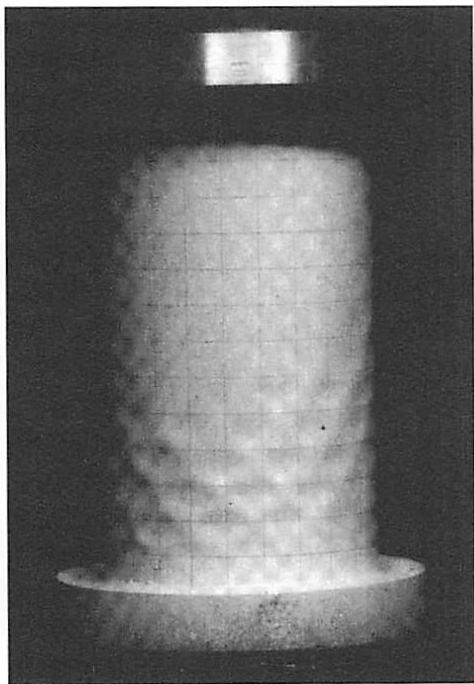

Stages of development of a common mushroom.

Bacterial growth.

Collapse of a smooth cylinder under buckling. Growth of quasi-crystals in alloys. Formation of a planetary moon. Generation of slime mold. A glass plate shattering.

Other examples are scattered in the text which follows in this chapter and the next.

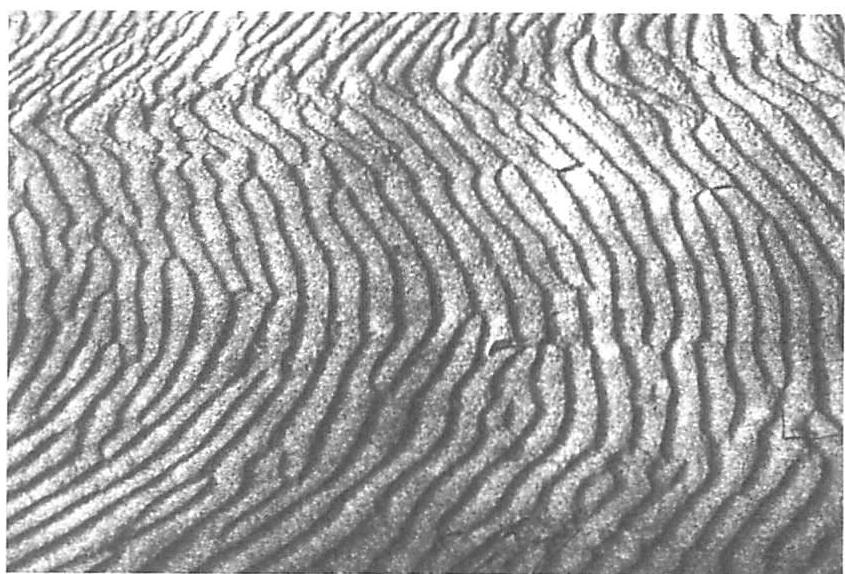

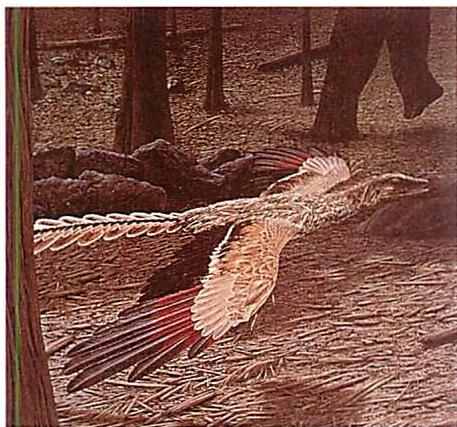

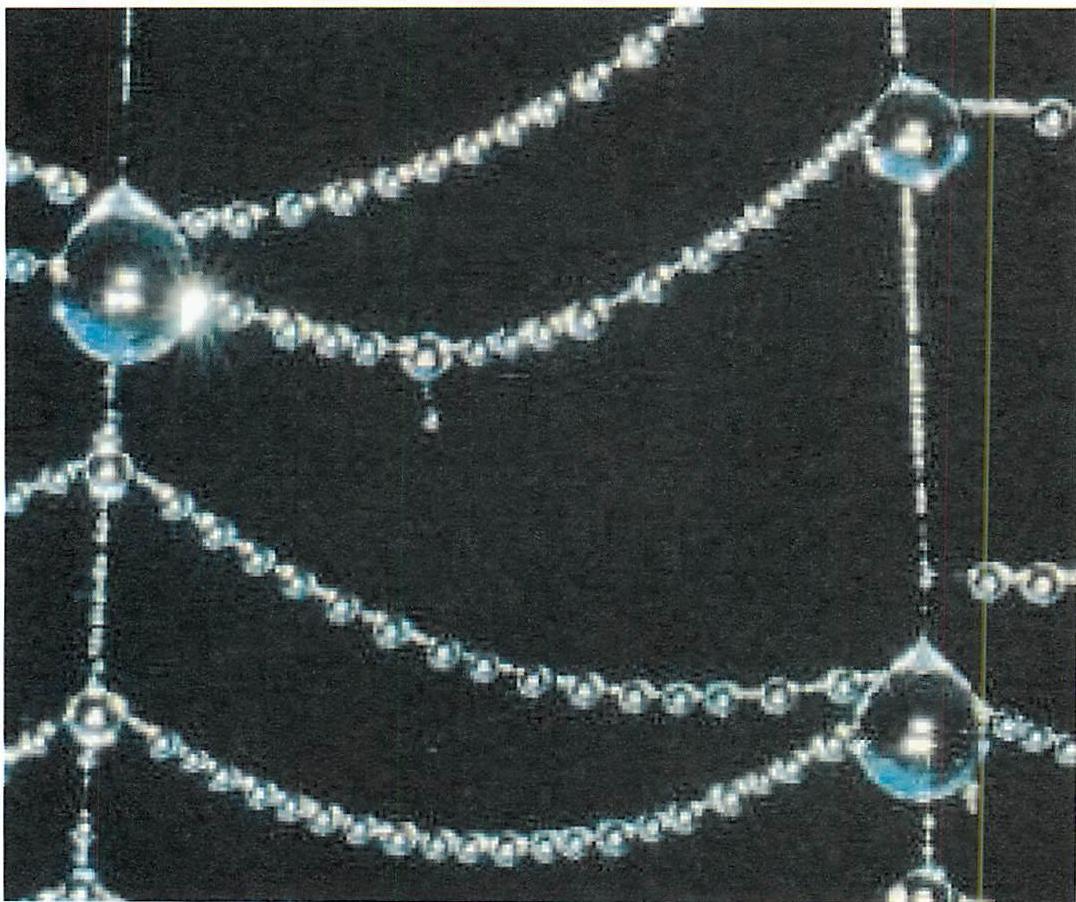

Sand waves forming in wind-blown sand. Growth of a snow crystal. Evolution of a river bed. Development of an angiosperm seed. Evolution of the feathers of archaeopteryx. The quantum process which creates electron orbits within atoms.

In all these cases, when we look at the sequence of development, we see a sequence which is essentially smooth in character.⁸ That means, within the sequence, each state follows, without breaking structure, from the state before. The structure of the state before (its wholeness) develops, evolves, changes—but is still visible in the next state. Even in those important cases where an entirely new structure is introduced—often the most important moments in the sequence—the new structure is still introduced in such a way as to maintain the essence, the underlying structure, of the previous state. This smoothness of evolution is visible in all the examples, essentially without exception. Even in those cases where there is a catastrophe—the mathematical term for the appearance of some new feature, not visible in the symmetries of the previous state—this catastrophe always begins as a feature which is essentially consistent with the symmetries of the earlier state, and which then develops, and continues to develop, as the new source of structure, thus still allowing a smooth and consistent evolution of structure.⁹

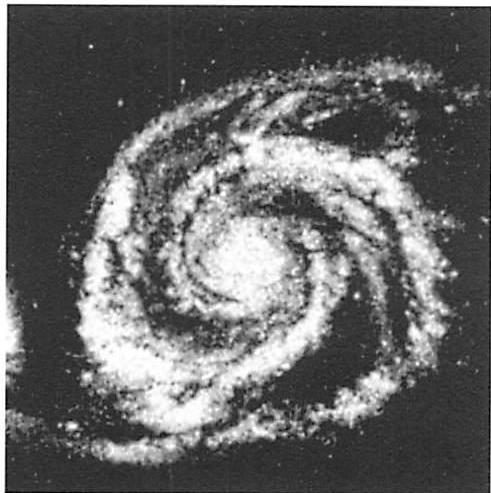

FORMATION OF A SPIRAL GALAXY - THE DRAMATIC SPIRALS OF M51

The genesis of the spiral form in a galaxy comes about because a disk of pre-galactic material, spinning as it does, includes some random motion. The random perturbations give rise to an oscillating pattern of gravitational waves of rarefaction and compression. As this wave system develops, it can go only to two or three large-scale forms. Much of the time, it goes to a two-armed spiral. The two-armed spiral is one of the simplest transforms of a slightly perturbed oscillating disk of material in which a gravitational wave appears.¹⁰ The second illustration shows a computer simulation of the process. When you break the infinite symmetry group of the rotating disk, you are left with the simplest symmetry group consistent with rotational motion: a spiral with arms.

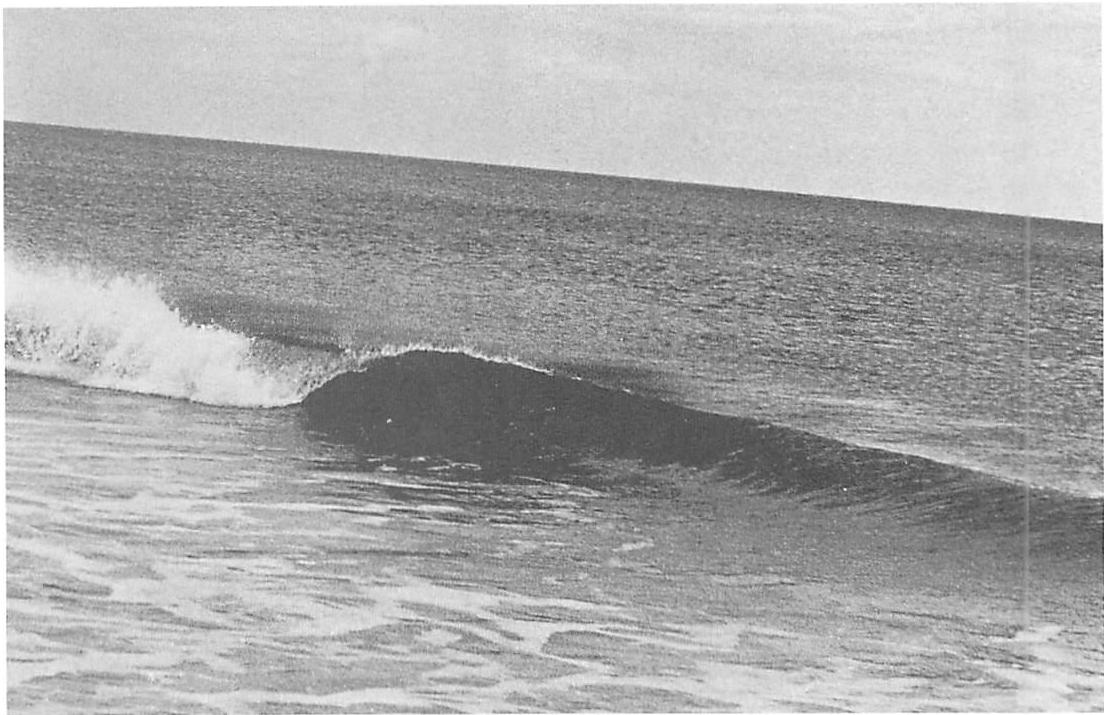

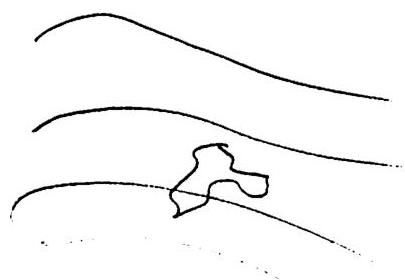

A BREAKING WAVE IN THE OCEAN

Here we have a catastrophe creating radical new structure. When the wave breaks, the smooth, curved top of the unbroken wave slowly becomes a point, and this point then curls over

when the wave breaks. Finally, the broken wave turns into many drops which form the splash.

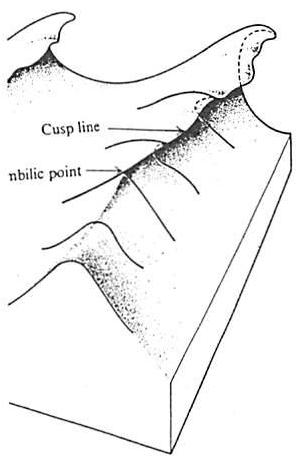

Even here, when the curve turns into a cusp with a sharp point, only one new differentiation is introduced. The system of centers which existed in the volume of the water, on the air-water interface and next to the water in the air, are, for the most part, maintained. One small bit of new structure is added—the cusp—and this tiny bit of structure, gradually introduced and extended, becomes more and more extensive in its impact, and finally makes the wave break, and forms an entirely new system of configurations.

In each case, if we look carefully at Thom's diagram, and at my diagram to the right, we see that the system of centers which constitutes the wholeness in the ongoing wave is extended and maintained and developed, but never violated.[11]

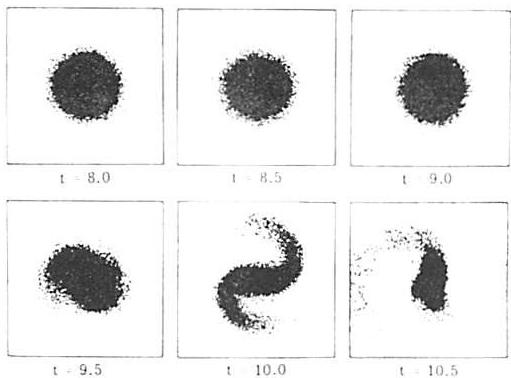

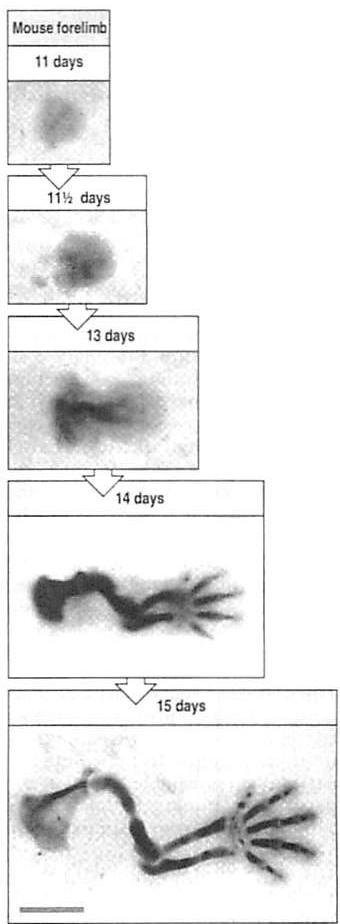

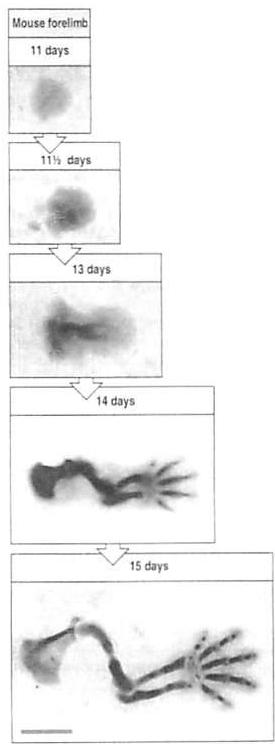

THE FORMATION OF A FROG EMBRYO

The embryo starts as a ball of cells. The ball splits down the middle. An axis is introduced. The wholeness of each stage is consistent with