The four books of The Nature of Order constitute the ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth in a series of books which describe an entirely new attitude to architecture and building. The books are intended to provide a complete working alternative to our present ideas about architecture, building, and planning — an alternative which will, we hope, gradually replace current ideas and practices.

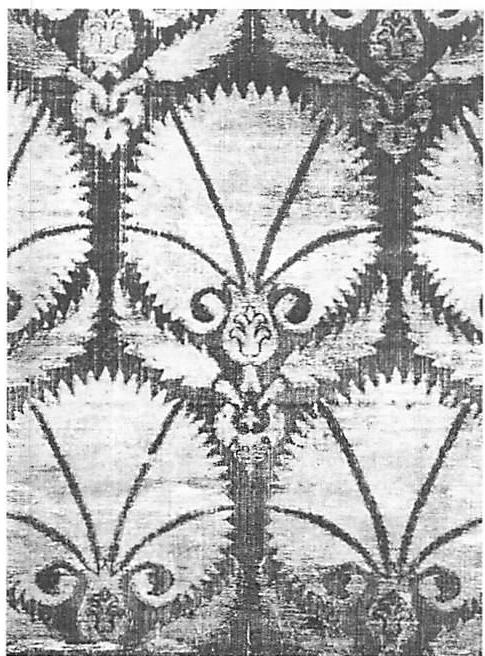

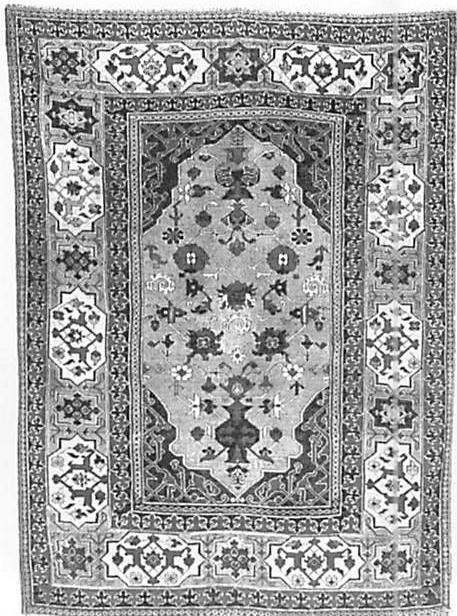

| Volume 1 | THE TIMELESS WAY OF BUILDING | | Volume 2 | A PATTERN LANGUAGE | | Volume 3 | THE OREGON EXPERIMENT | | Volume 4 | THE LINZ CAFE | | Volume 5 | THE PRODUCTION OF HOUSES | | Volume 6 | A NEW THEORY OF URBAN DESIGN | | Volume 7 | A FORESHADOWING OF 21ST CENTURY ART: THE COLOR AND GEOMETRY OF VERY EARLY TURKISH CARPETS | | Volume 8 | THE MARY ROSE MUSEUM | | Volumes 9 to 12 | THE NATURE OF ORDER: AN ESSAY ON THE ART OF BUILDING AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE | | Book 1 | THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE | | Book 2 | THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE | | Book 3 | A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD | | Book 4 | THE LUMINOUS GROUND |

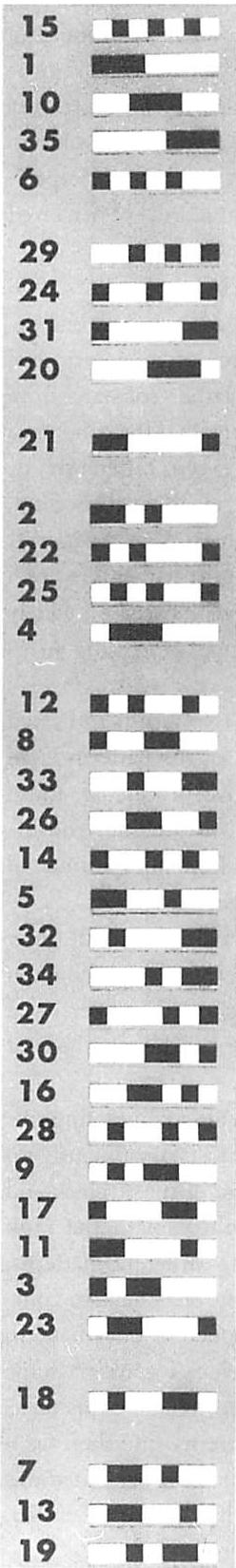

Future volume now in preparation

| Volume 13 | BATTLE: THE STORY OF A HISTORIC CLASH BETWEEN WORLD SYSTEM A AND WORLD SYSTEM B |

THE NATURE OF ORDER

An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe

BOOK ONE THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

BOOK TWO THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

BOOK THREE A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

BOOK FOUR THE LUMINOUS GROUND

THE CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL STRUCTURE in BERKELEY CALIFORNIA in association with PATTERNLANGUAGE.COM

© 2002 CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

PREVIOUS VERSIONS

© 1980, 1983, 1987, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001 CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

Published by The Center for Environmental Structure 2701 Shasta Road, Berkeley, California 94708

CES is a trademark of the Center for Environmental Structure. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Center for Environmental Structure.

ISBN 978-0-9726529-1-9 (Book 1) ISBN 978-0-9726529-0-2 (Set)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Alexander, Christopher. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe / Christopher Alexander, p. cm. (Center for Environmental Structure Series; v. 9-12).

Contents: v.1. The Phenomenon of Life — v.2. The Process of Creating Life v.3. A Vision of a Living World — v.4. The Luminous Ground

- Architecture—Philosophy. 2. Science—Philosophy. 3. Cosmology

- Geometry in Architecture. 5. Architecture—Case studies. 6. Community

- Process philosophy. 8. Color (Philosophy).

I. Center for Environmental Structure. II. Title. III. Title: The Phenomenon of Life. IV. Series: Center for Environmental Structure series; v. 9.

NA2500.A444 2002 720.1—dc21 2002154265 ISBN 978-0-9726529-1-9 (cloth: alk. paper: v.1)

Typography by Katalin Bende and Richard Wilson Manufactured in China by Everbest Printing Co., Ltd.

BOOK ONE: THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

PROLOGUE TO BOOKS 1-4

THE ART OF BUILDING AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . 1

PREFACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

PART ONE

- THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

- DEGREES OF LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

- WHOLENESS AND THE THEORY OF CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . 79

- HOW LIFE COMES FROM WHOLENESS . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

- FIFTEEN FUNDAMENTAL PROPERTIES . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

- THE FIFTEEN PROPERTIES IN NATURE . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

PART TWO

- THE PERSONAL NATURE OF ORDER . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

- THE MIRROR OF THE SELF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 313

- BEYOND DESCARTES: A NEW FORM OF SCIENTIFIC OBSERVATION . . 351

- THE IMPACT OF LIVING STRUCTURE ON HUMAN LIFE . . . . . . 371

- THE AWAKENING OF SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 403

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 441

APPENDICES: MATHEMATICAL ASPECTS OF WHOLENESS AND LIVING STRUCTURE . . 445

BOOK TWO: THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

PREFACE: ON PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

PART ONE: STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS

- THE PRINCIPLE OF UNFOLDING WHOLENESS . . . . . .. . . . . . . . 15

- STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

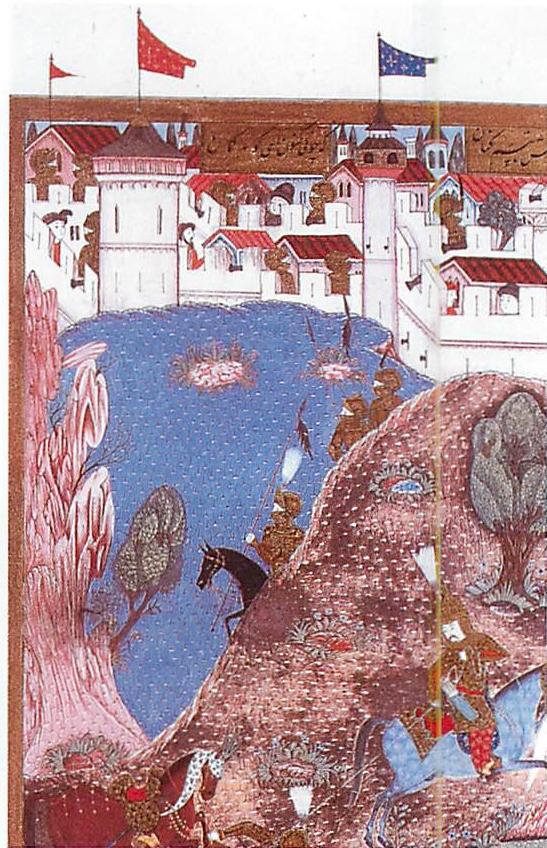

- STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRADITIONAL SOCIETY .. . 79

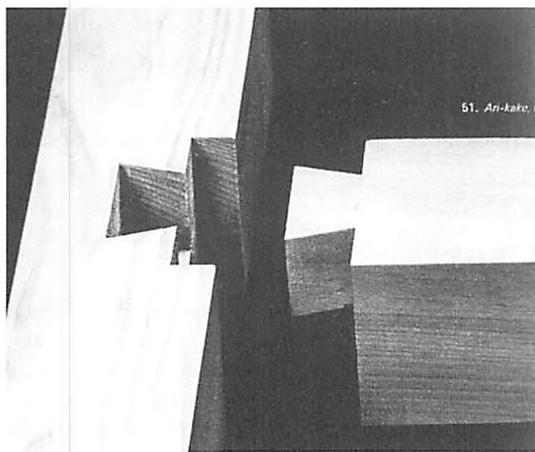

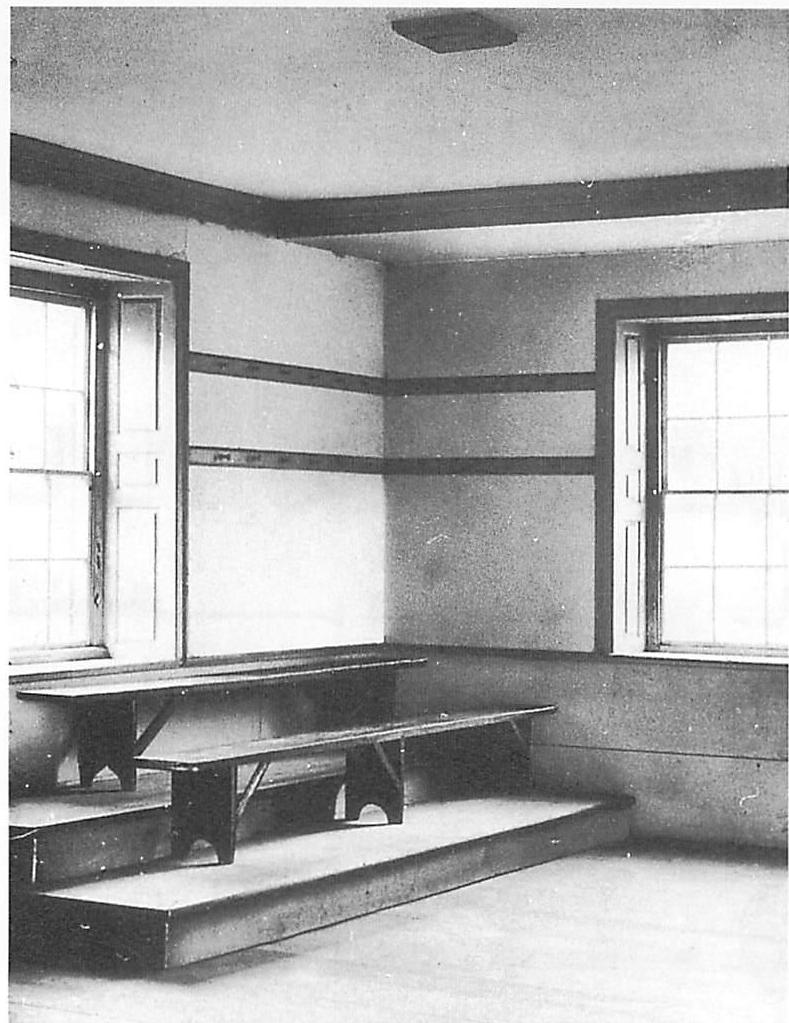

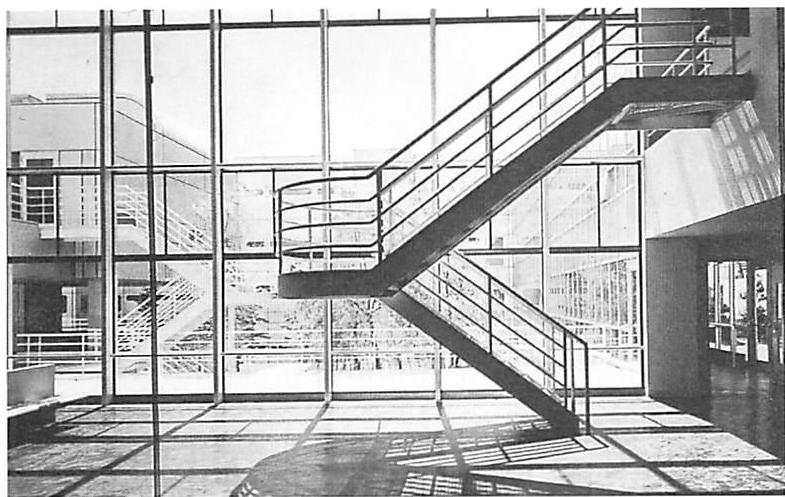

- STRUCTURE-DESTROYING TRANSFORMATIONS IN MODERN SOCIETY . . . . . . 101

INTERLUDE

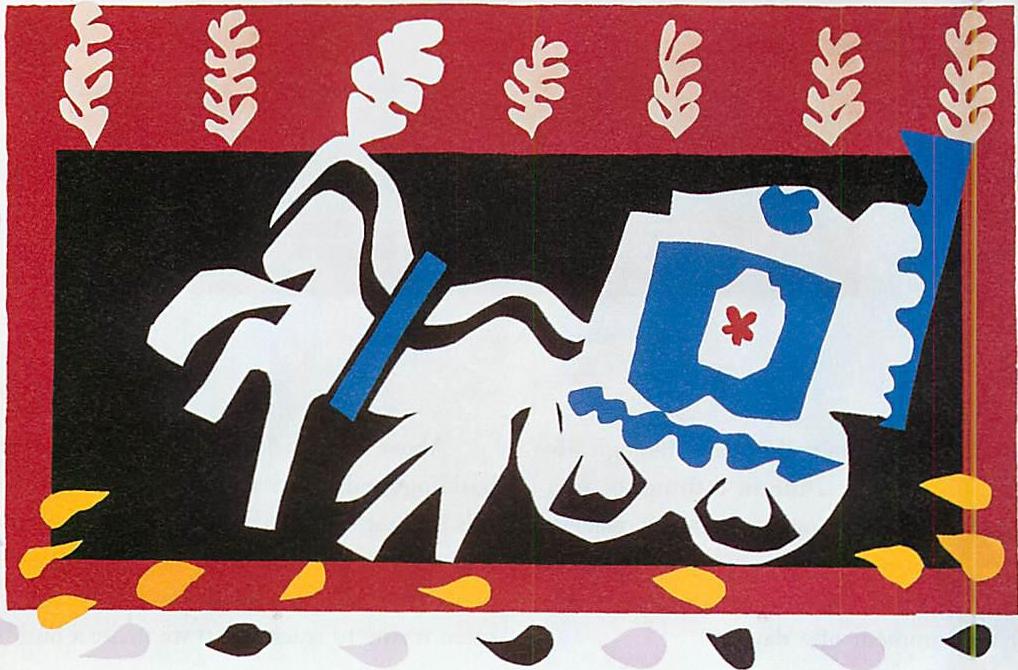

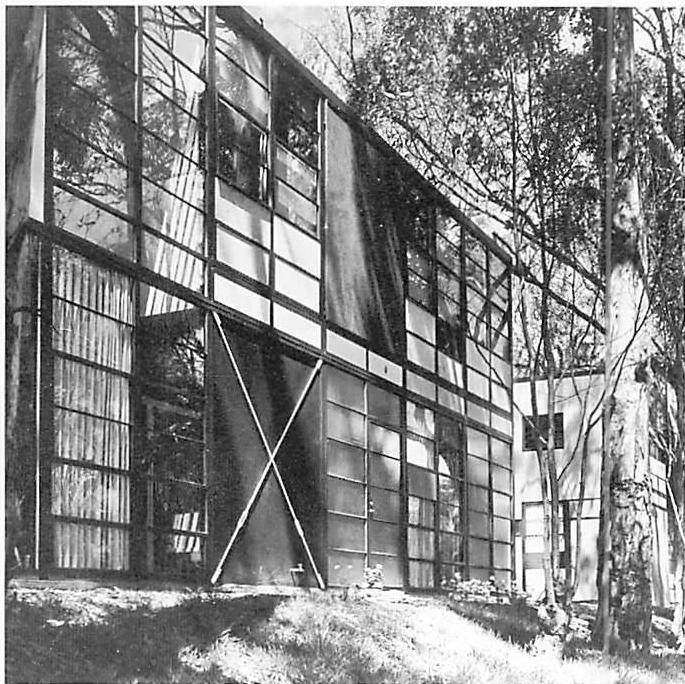

- LIVING PROCESS IN THE MODERN ERA: TWENTIETH-CENTURY CASES WHERE LIVING PROCESS DID OCCUR . . . . . . . . . . . 131

PART TWO: LIVING PROCESSES

- GENERATED STRUCTURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

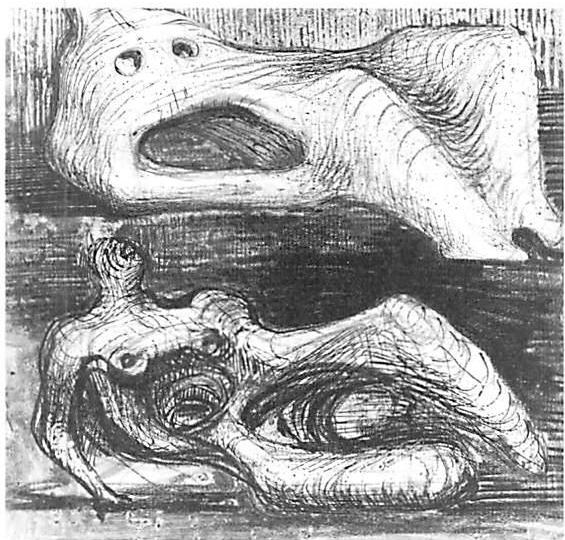

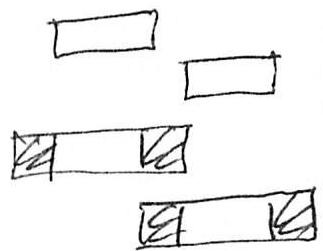

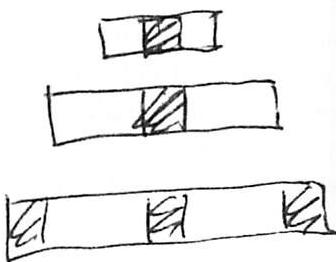

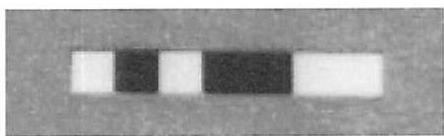

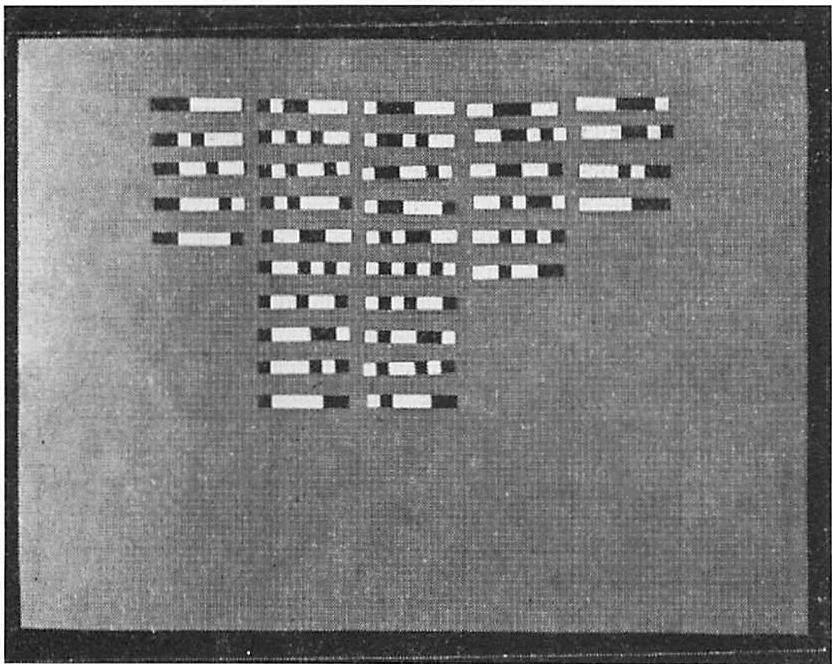

- A FUNDAMENTAL DIFFERENTIATING PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193

- STEP-BY-STEP ADAPTATION . . . . . . . . . . . 217

- ALWAYS HELPING TO ENHANCE THE WHOLE. . . . . . . . . . . . . 237

- ALWAYS MAKING CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

- THE SEQUENCE OF UNFOLDING . . . . . . . . . . . . 287

- EVERY PART UNIQUE . . . . . . . . . . . 311

- PATTERNS: RULES FOR MAKING CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . 329

- DEEP FEELING . . . . . . . . . . . 357

- EMERGENCE OF FORMAL GEOMETRY . . . . . . . . . . 387

- FORM LANGUAGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 415

- SIMPLICITY . . . . . . . . . . . . . 439

PART THREE: A NEW PARADIGM FOR PROCESS IN SOCIETY

- THE CHARACTER OF PROCESS IN SOCIETY . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . 473

- MASSIVE PROCESS DIFFICULTIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 489

- THE SPREAD OF LIVING PROCESSES THROUGHOUT SOCIETY . . . . . . 511

- THE ARCHITECT IN THE THIRD MILLENIUM . . . . . . . . . . . 531

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . 541

APPENDIX: AN EXAMPLE OF A LIVING PROCESS: BUILDING A HOUSE . . . . . . 547

BOOK THREE: A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

PREFACE: THE FUNDAMENTAL PROCESS REPEATED TEN MILLION TIMES . . . 1

PART ONE

- OUR BELONGING TO THE WORLD: PART ONE. . . . . . . . . . 21

- OUR BELONGING TO THE WORLD: PART TWO . . . . . . . . . 39

PART TWO

- THE HULLS OF PUBLIC SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

- THE FORM OF PUBLIC BUILDINGS . . . . . . . . . . . 99

- PRODUCTION OF GIANT PROJECTS . . . . . . . . . . . 147

- THE POSITIVE PATTERN OF SPACE AND VOLUME IN THREE DIMENSIONS ON THE LAND. . . . . . . . . . . 165

- POSITIVE SPACE IN STRUCTURE AND MATERIALS . . . . . . 199

- THE CHARACTER OF GARDENS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

PART THREE

- FORMING A COLLECTIVE VISION FOR A NEIGHBORHOOD . . . . . 267

- RECONSTRUCTION OF AN URBAN NEIGHBORHOOD . . . . . . 291

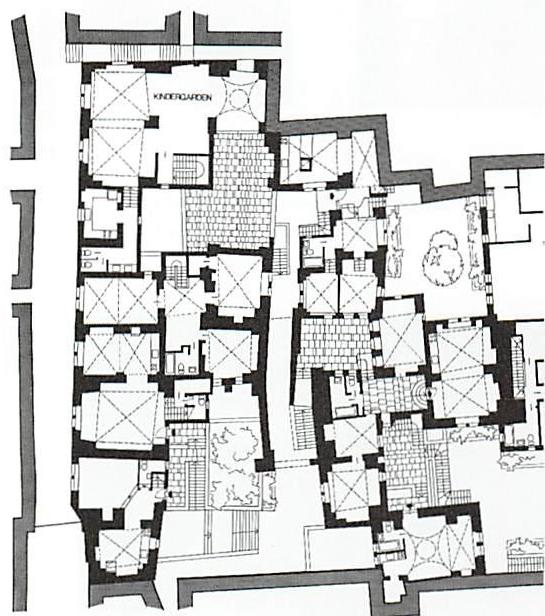

- HIGH DENSITY HOUSING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 323

- FURTHER DYNAMICS OF A GROWING NEIGHBORHOOD . . . . . 343

PART FOUR

- THE UNIQUENESS OF PEOPLE’S INDIVIDUAL WORLDS . . . . . 365

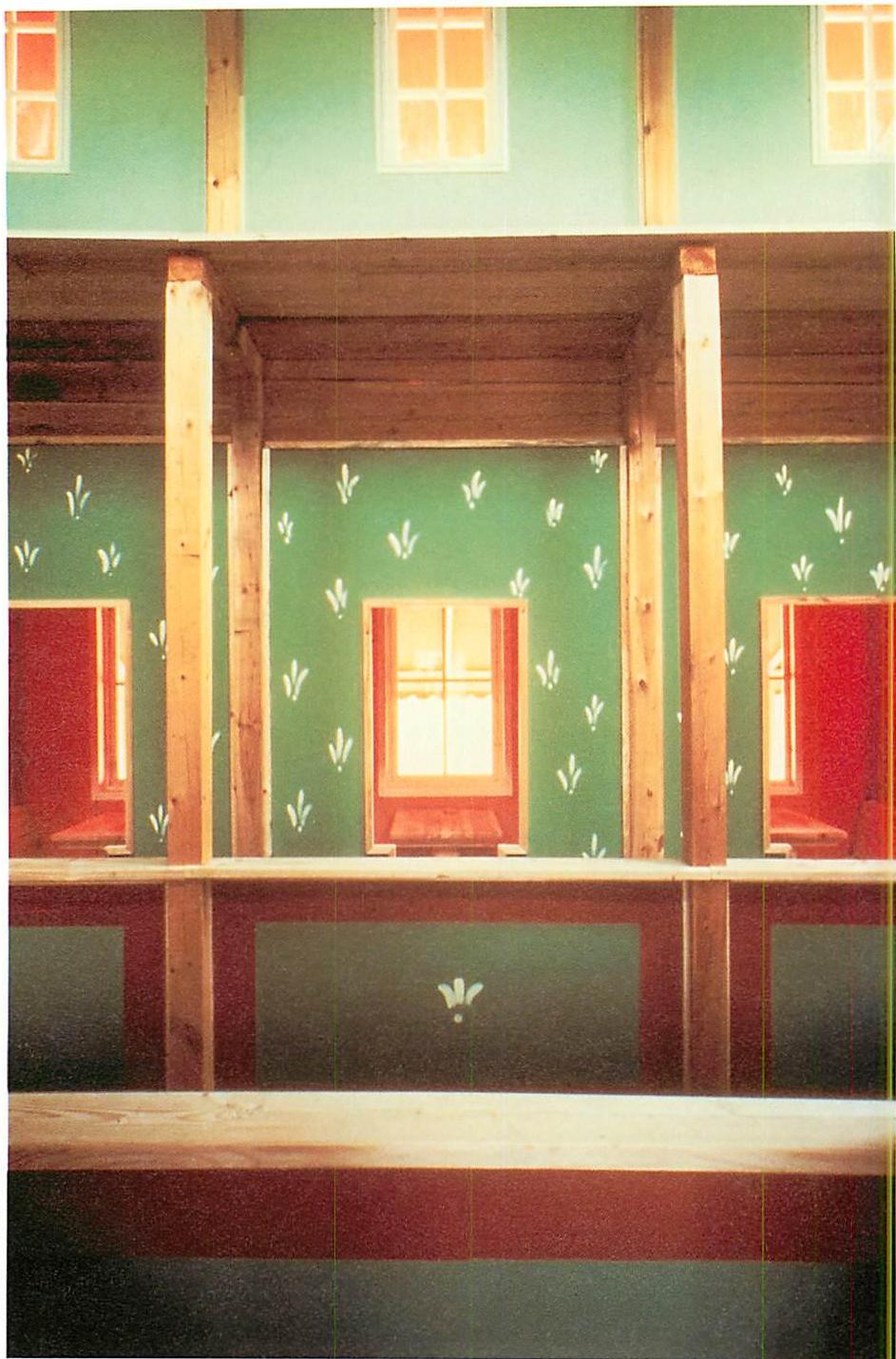

- THE CHARACTER OF ROOMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 405

PART FIVE

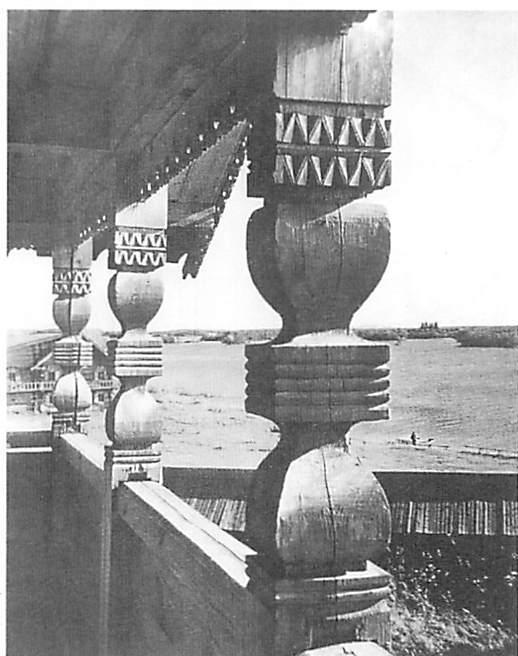

- CONSTRUCTION ELEMENTS AS LIVING CENTERS . . . . . . 439

- ALL BUILDING AS MAKING . . . . . . . . . . . . . 473

- ACTIVE INVENTION OF NEW BUILDING TECHNIQUES . . . . 507

PART SIX

- ORNAMENT AS A PART OF ALL UNFOLDING . . . . . . 543

- COLOR WHICH UNFOLDS FROM THE CONFIGURATION . . . . 577

EPILOGUE: THE MORPHOLOGY OF LIVING ARCHITECTURE ARCHETYPAL FORM: . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 601

CONCLUSION: THE WORLD CREATED AND TRANSFORMED . . . . 637

BOOK FOUR: THE LUMINOUS GROUND

PREFACE: TOWARDS A NEW CONCEPTION OF THE NATURE OF MATTER . . . I

PART ONE

- OUR PRESENT PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . . . . . . . 11

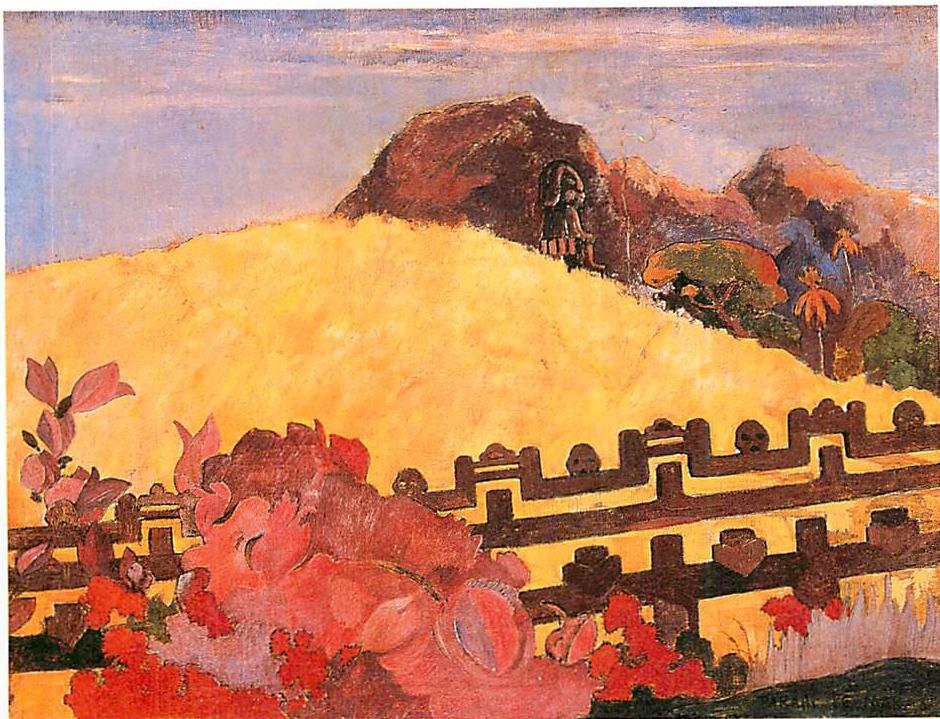

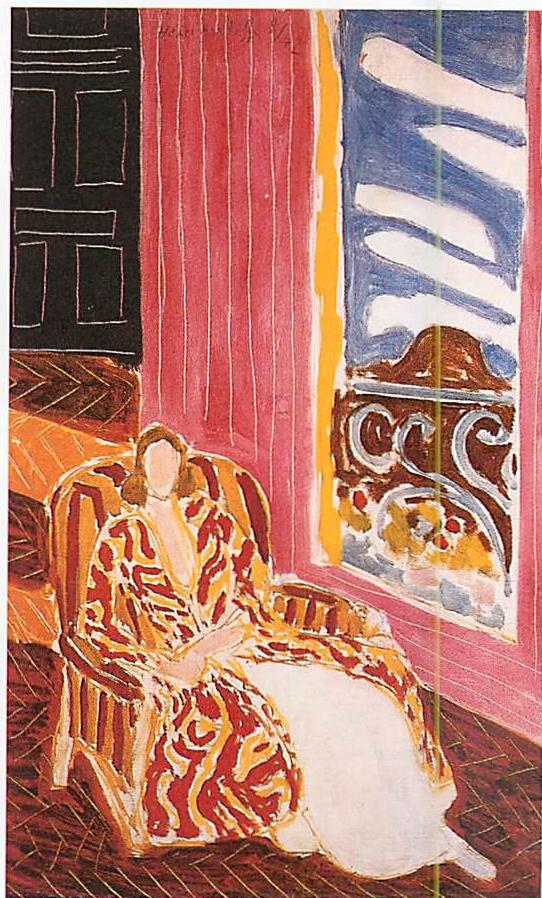

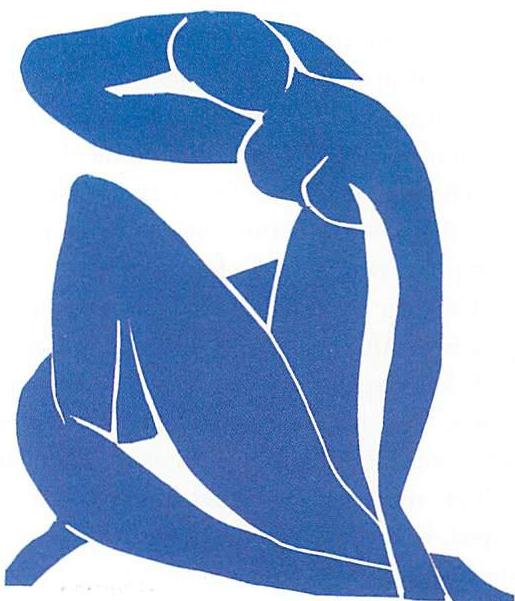

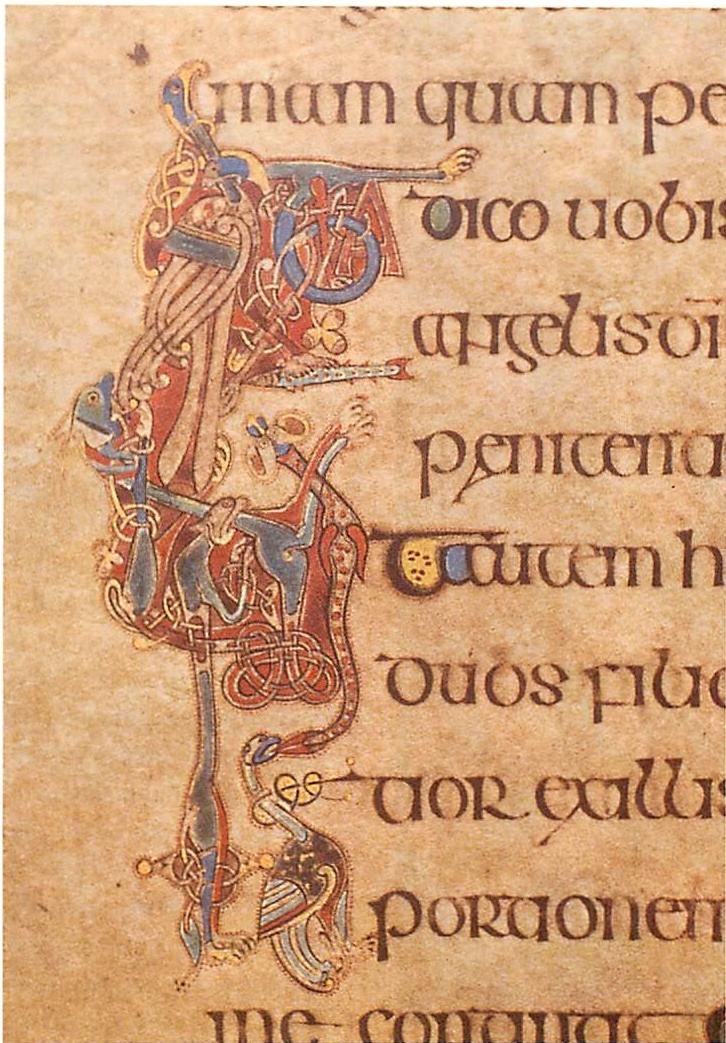

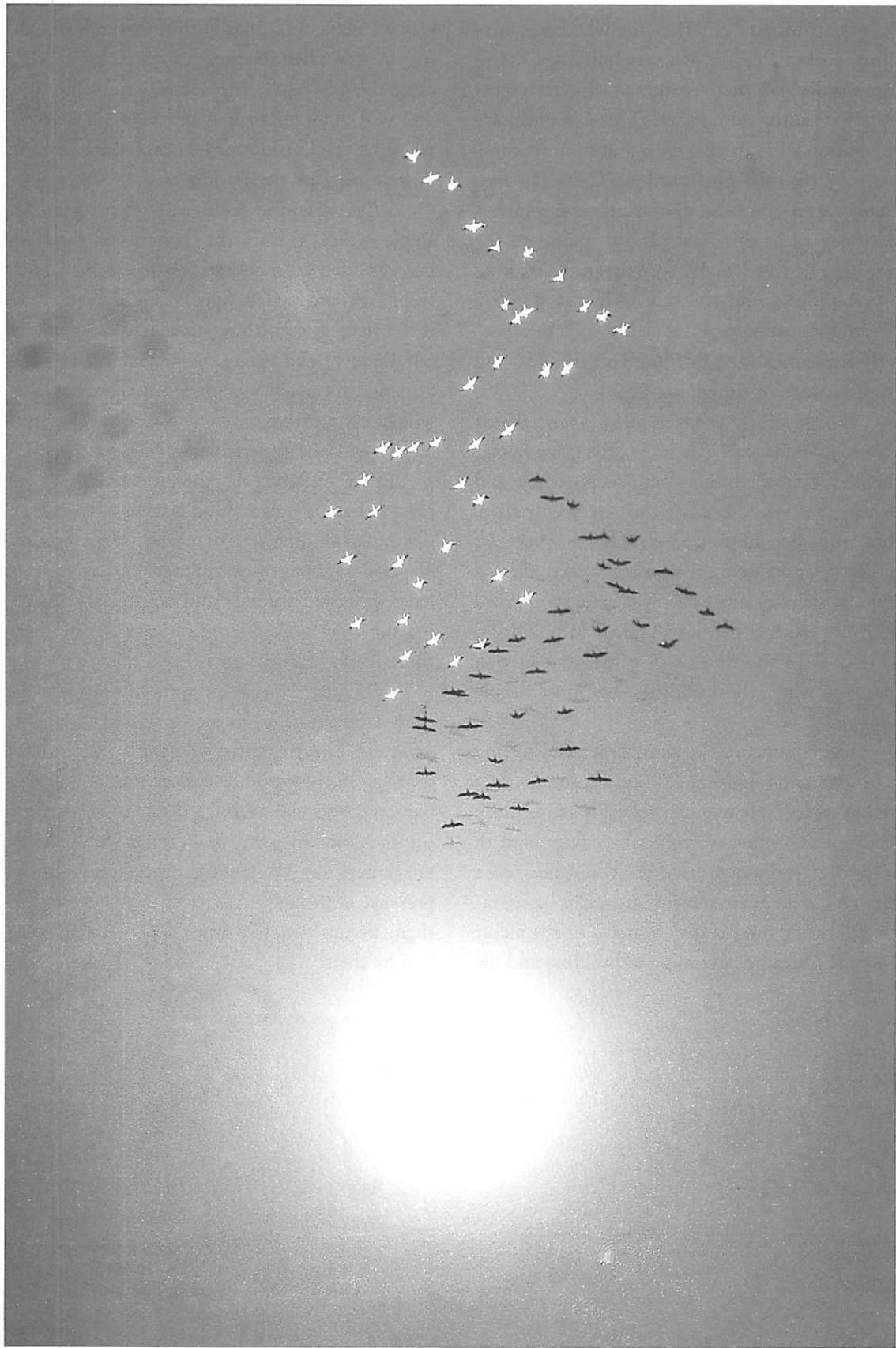

- CLUES FROM THE HISTORY OF ART. . . . . . . . 29

- THE EXISTENCE OF AN "I" . . . . . . . . . . 49

- THE TEN THOUSAND BEINGS. . . . . . . 73

- THE PRACTICAL MATTER OF FORGING A LIVING CENTER. . . . . . . . . . . 111 MID-BOOK APPENDIX: RECAPITULATION OF THE ARGUMENT. . . . . . . . . 135

PART TWO

- THE BLAZING ONE . . . . . . . . . . . 145

- COLOR AND INNER LIGHT. . . . . . . . 157

- THE GOAL OF TEARS . . . . . . . 241

- MAKING WHOLENESS HEALS THE MAKER. . . . . . . . . . . . . 261

- PLEASING YOURSELF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271

- THE FACE OF GOD . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . 301

CONCLUSION TO THE FOUR BOOKS

A MODIFIED PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . .. . . . 317 EPILOGUE: EMPIRICAL CERTAINTY AND ENDURING DOUBT . . . . . . . . 339 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . 347

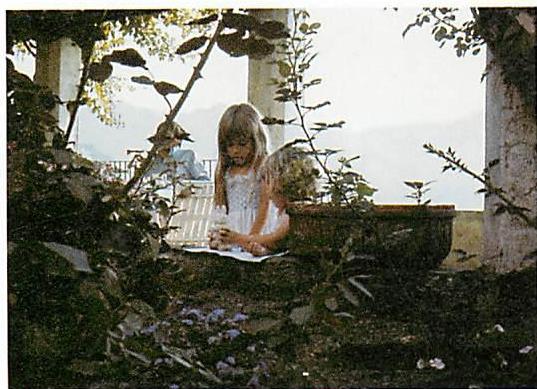

DEDICATION

I DEDICATE THESE FOUR BOOKS TO MY FAMILY:

TO MY BELOVED MOTHER, WHO DIED MANY YEARS AGO;

TO MY DEAR FATHER, WHO HAS ALWAYS HELPED ME AND INSPIRED ME;

TO MY DARLINGS LILY AND SOPHIE;

AND TO MY DEAR WIFE PAMELA WHO GAVE THEM TO ME,

AND WHO SHARES THEM WITH ME.

THESE BOOKS ARE A SUMMARY OF WHAT I HAVE UNDERSTOOD ABOUT

THE WORLD IN THE SIXTY-THIRD YEAR OF MY LIFE.

THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

PROLOGUE TO BOOKS I-4: THE ART OF BUILDING AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE

The activity we call building creates the physical order of the world, constantly, unendingly, day after day. In the last five millennia, human beings have created millions upon millions of cubic yards of building, and millions of buildings, houses, roads, and cities — entire worlds. Our world is dominated by the order we create.

But although we are responsible for the creation of order on this enormous scale, we hardly even know what the word "order" means. Our present idea of "order" is obscure. Although the word is often used informally by artists and biologists and physicists — usually to stand for some deep regularity we cannot quite define — we need a better understanding of the deep geometric reality of order. If we are honest we must admit we hardly even know what kind of phenomenon it is. Yet we build the world, producing its order, day by day. Thus we go on, willy-nilly creating order in the world, without knowing what it is, why we are doing it, what its significance might be.

In physics and biology some progress has been made toward understanding the phenomenon of order, and the processes which create order. The creation of living organisms through the morphogenetic process, the creation of matter, the creation of stars and galaxies from nuclear fire, the constant creation of particles by interaction with one another — have all been studied in the last seventy years. In these limited cases we now have

a rudimentary idea of the way the order-creation works. It has become clear, too, that the way the order is created in these cases is of essential importance to our understanding of the world. Our knowledge of order-creating processes in physics, chemistry, and biology has molded the modern view of the universe.

The art of building has not, so far, had a comparable impact on our understanding of the world. Our modern picture of the universe, what kind of stuff space and matter is made of, has not been influenced by building or by architecture. Yet, I shall argue, the process of building is an order-creating process of no less importance than those of physics and biology. It is vast in its scale and scope. It is almost universal in our experience. It is therefore reasonable to think that the art of building might give us equally essential insights.

In what follows I shall try to show that there is a way of understanding order which is general and does do justice to the nature of building and of architecture. It is a view which, I hope, is adequate to understanding the intuitions we have about beauty and the life of buildings. It is a view which tells us what it means for a building to be a great building, and when a building is working properly. It is, I believe, a common-sense and powerful view, with practical results.

If you accept the view of order I am proposing, you will find it has unexpected intellectual

results. It modifies our view of the physical universe and the way the universe is put together. Thus, what starts out as a way of understanding architecture ends up, also, as a view which may affect our understanding of physics and biology. When we understand the art of building from this point of view of order, it not only changes our understanding of the building process, but also has the capacity to change our cosmology.

I did not start out as a philosopher, and I have no special desire to write about philosophy or about the nature of things. This is not my trade. I am interested in one question above all—how to make beautiful buildings. But I am interested only in real beauty. I was never interested in making the kinds of slick buildings which architects of my time have generally been making. They have, in many cases, given up the making of real beauty—and have, by implication, even given it up as an attainable ideal. This is perhaps understandable. Making buildings at the level of beauty which was common in 12th- or 15th-century Europe and in hundreds of other cultures in almost all eras of human history except our own is very hard for us. It was especially hard for us, in the late 20th century, and will continue to be as we enter the 21st. For some reason—not at first entirely clear to me thirty-five years ago—it is a matter of such difficulty for us that architects have almost given it up. But I have not been willing to do so. I never agreed to put up with second best, or to accept the almost silly idea of “good architecture” which certain 20th-century architects have foisted on the public. I wanted to be able to do the real thing—and for that I had to know what the real thing is. The reason was not intellectual curiosity—but only the practical reason that I wanted to be able to do it myself.

Thinking about these matters has been extremely difficult. It has taken me thirty-five years to think my way out of the intellectual thicket where I started. And I believe this intellectual confusion is shared today by almost every architect. I am at heart a very empirical person. I try to think carefully about things, and I want them

to make sense. Again and again I found that there are issues in the making of buildings where our modern mentality—our way of looking at the world—makes it hard, or impossible, to come to grips with the facts as they really are.

Issues which were straightforward in other ages—such as spirit, for example, or the life that can exist in stone—are inadmissible for us. I found it almost unbearablely difficult to accept some of the theoretical concepts I was led to in the course of my work on these topics. Yet the problems we must face if we are to make things beautiful kept me coming, again and again, to fundamental questions about the nature of matter, and about the nature of the empiricist tradition—especially the tradition which we ascribe to René Descartes.

As a scientist trained in mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge, I found that I was sometimes formulating concepts which were hard to believe. Sometimes I felt I was betraying my training. The new principles I discovered seemed questionable. It was, in many cases, even embarrassing to formulate them, very hard to allow myself to think these thoughts. I stood looking always at my empiricist tradition, and at the tradition of thought which I learned at Cambridge, and felt ashamed sometimes to be saying such things. But the facts I encountered were stronger than my squeamishness. I found that I was able to construct a coherent view of order, one which deals honestly with the nature of beauty, but only by formulating new and surprising concepts about the nature of space and matter. In the end, it was my respect for empirical truth that made me give up my doubts, and gave me the strength to formulate conceptions which are—for an empiricist of 20th-century training—suspicious or potentially ridiculous.

Even now, on some days I look at the theory I have formulated in these four books and can hardly believe that it is true. It provides a view of the universe which is so surprising, and so much at odds with the normal common-sense ways of thinking about physical reality we have currently, that it seems almost like a fantasy, like

some kind of science fiction. But then, on other days, I go through the arguments again and realize that no matter how strange these ideas are, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that they must be true. There seems to be no alternative way of putting things together — at least not one that I have been able to discover — in which we get a proper view of the things that are important.

Skeptical readers will share my doubt about the intellectual formulations I have presented. Some of the formulations will seem very hard indeed to swallow. But for that very reason, and since it is above all the skeptical reader whom I would like to persuade, I express my own doubt about what I have done, and confess to a squeamishness which must be at least as great, perhaps even greater, than that of the most skeptical reader. Yet in the end I do believe that what I have written here is true.

As a child I was always impressed by Saint Teresa. She was a 16th-century Spanish Carmelite nun who — so history tells us — was made a saint not because she believed so intensely in God, but because of her doubt. Most of the time she did not believe in God. Only now and then she did believe. But she never gave up her struggle and her doubt. She struggled with her faith, and, in the midst of her doubt and disbelief, found occasionally for a few moments that indeed she did believe. For this she was canonized.

I have always identified with Saint Teresa. Her confusion and her honesty seem very typical of our own age. Much of the time I find myself wondering if the theory I have presented in this book can really be true, or if I have merely concocted some fantastic fiction. But occasionally, in a few lucid moments, I see clearly, and it seems to me that it must be true, simply because there is no other explanation which is equally convincing and covers all the facts. Then in another instant I am doubting again, because it is just too difficult for a hard-boiled empiricist like me to believe that the metaphysical part, especially, of what I have written, and my analysis of the nature of space and matter, really can be true.

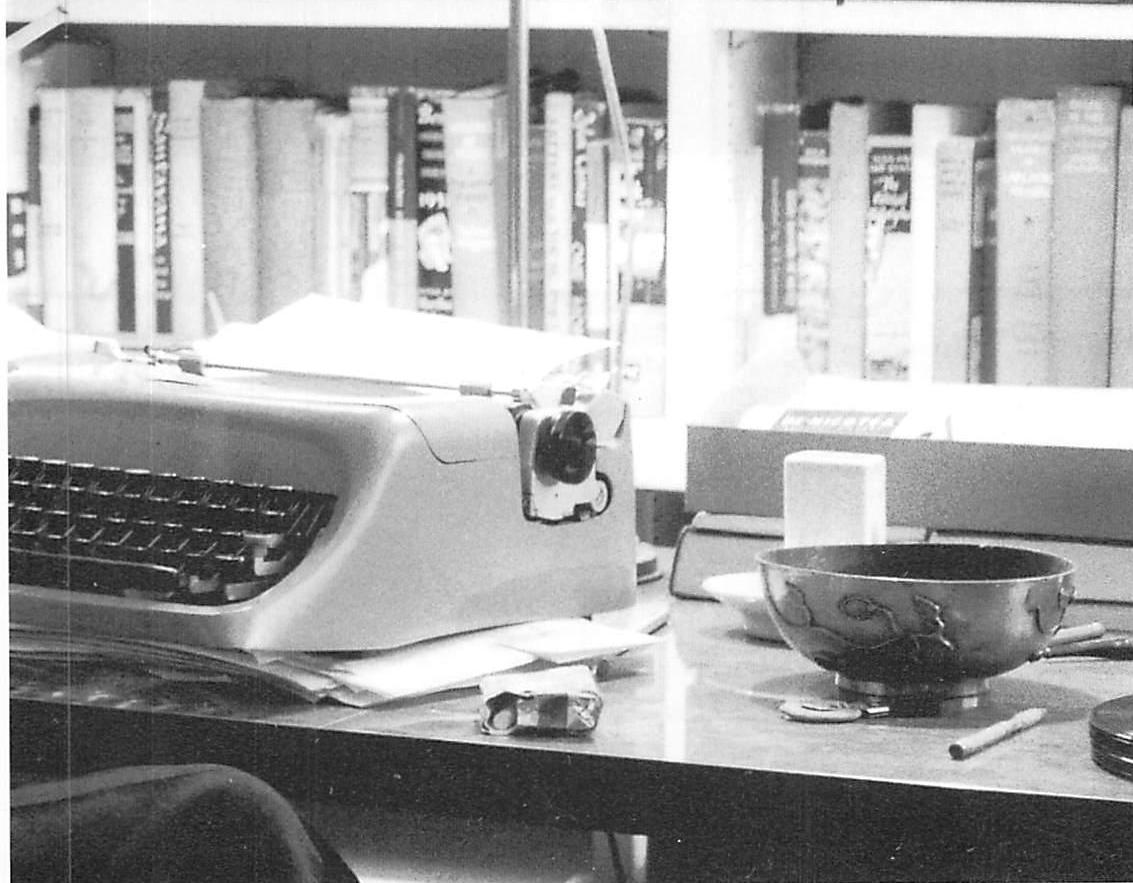

A few years ago, I was asked to go to the premiere of a film which had been made about my work. I was reluctant to go. It was a weekend, and I wanted to be with my family. In the end, though, we all decided to go together, Pamela and Lily and Sophie and I. The film was being shown at a film festival in San Francisco, at an old movie-house in the Mission district. We went in, they were showing all kinds of art films and new films one after the other, mainly fairly short ones. We sat through several of these films. Then mine came along, half an hour long. When the lights went up, I stood up. I had been asked to come forward and answer some questions.

To my surprise people started cheering. I was astonished. Of course touched, very moved. But to be honest I couldn't quite understand the reason for it. Of course I liked it. But anyway, it still seemed inexplicable.

I walked up to the stage, and people kept cheering and clapping. When I got there, the lights were very bright. They began asking questions, I gave not very good answers, the lights were so bright. We went along for a few minutes like that.

Then someone asked me, How did you come up with the pattern language? How did you get the actual material?

I said, "Well, it was not so very different from any other kind of science. My colleagues and I made observations, looked to see what worked, studied it, tried to distill out the essentials, and wrote them down."

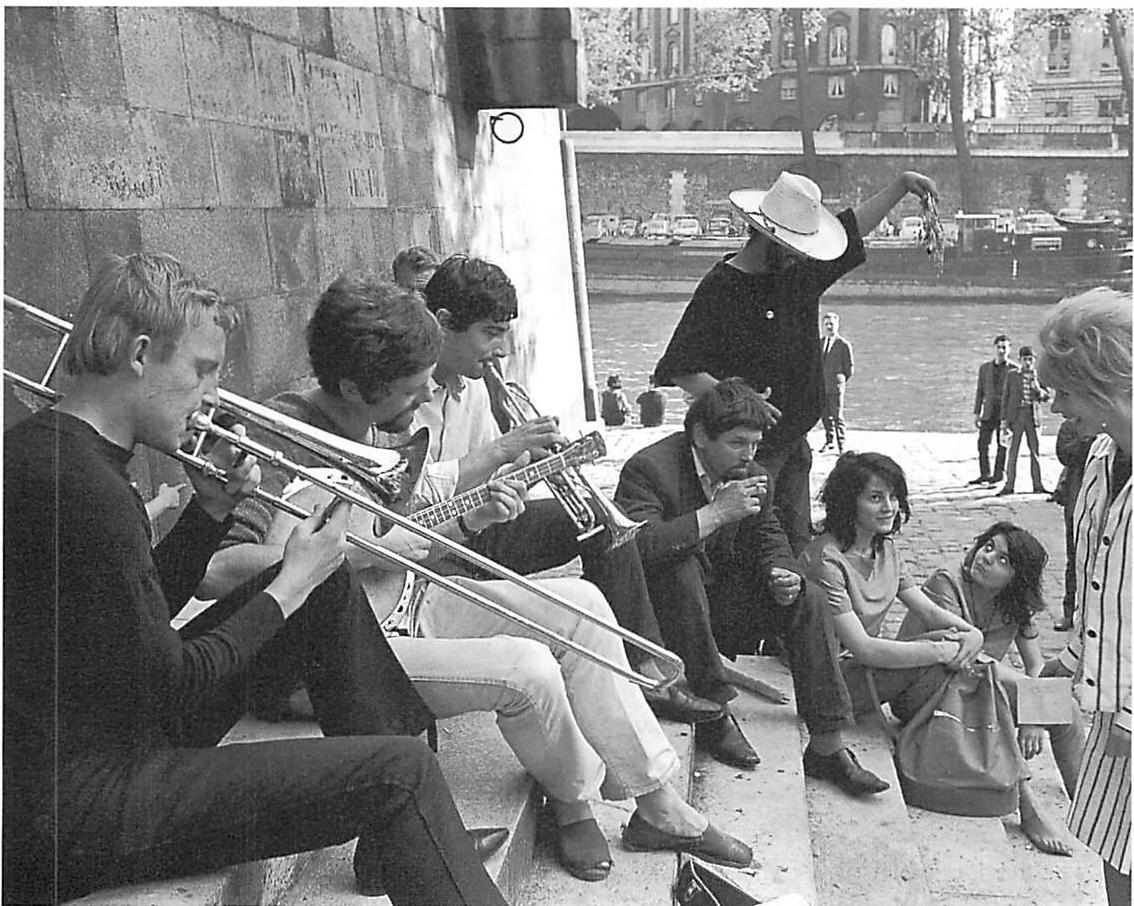

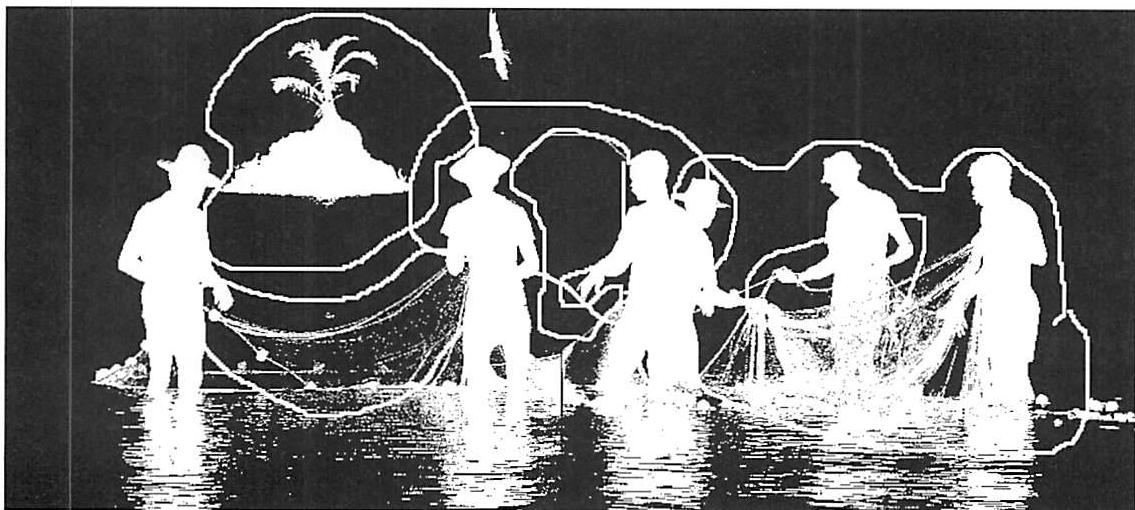

"But," I went on, "we did do one thing differently. We assumed from the beginning that everything was based on the real nature of human feeling and — this is the unusual part — that human feeling is mostly the same, mostly the same from person to person, mostly the same in every person. Of course there is that part of human feeling where we are all different. Each of us has our idiosyncrasies, our unique individual human character. That is the part people most often concentrate on when they are talking about feelings, and comparing feelings. But that idiosyn-

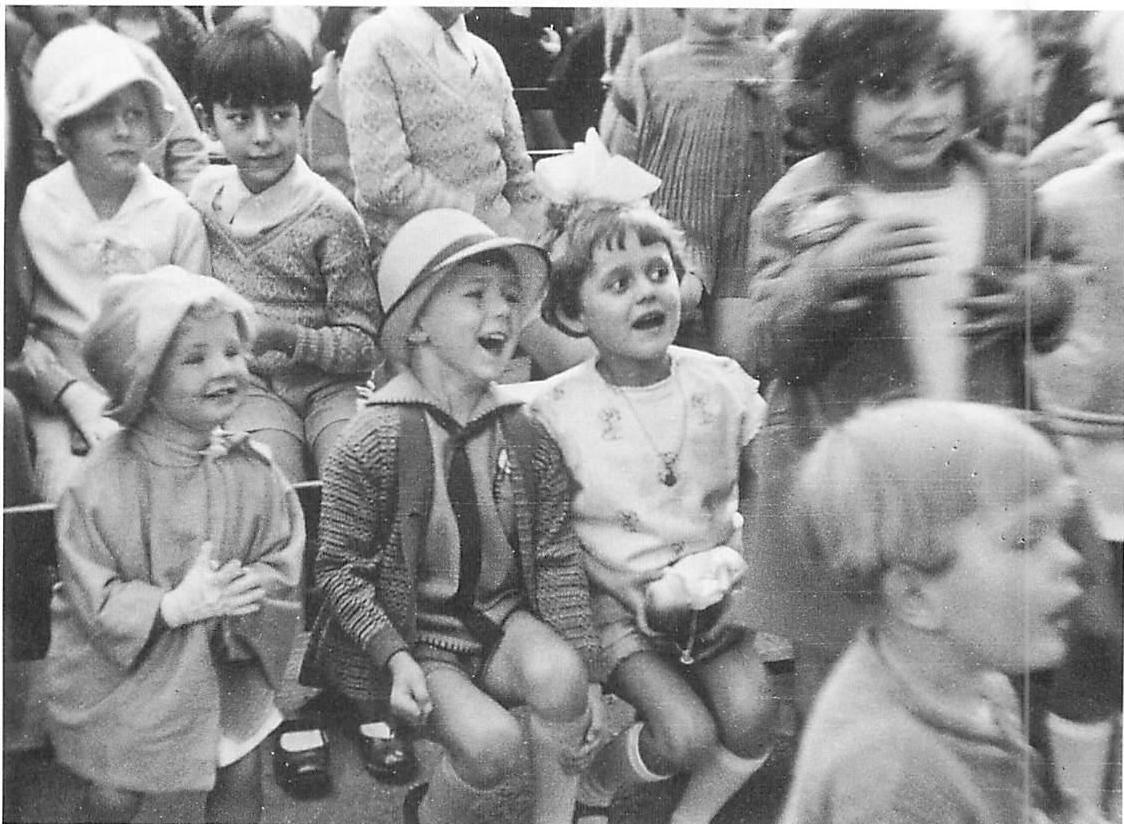

cratic part is really only about ten percent of the feelings which we feel. Ninety percent of our feelings is stuff in which we are all the same and we feel the same things. So, from the very beginning, when we made the pattern language, we concentrated on that fact, and concentrated on that part of human experience and feeling where our feeling is all the same. That is what the pattern language is—a record of that stuff in us, which belongs to the ninety percent of our feeling, where our feelings are all the same.”

When I said this, a sort of cry went up, people shouted and clapped again, stood up and cheered. Then dimly I began to understand why they had been clapping when I first came forward. What they saw in me was a voice saying that our shared human feeling has been forgotten, hidden in the mess of opinion and personal differences. What people find, and what moves them, in all the work which my colleagues and I have been doing for so many years, is that we have tried to honor and respect the reality of this huge ocean—this ninety percent of our self—in which our feelings are all alike. The fact that this huge basis, this huge ocean, has been forgotten—and has, perhaps, in my own works been reawakened—that is what brought them there that day to see that film, that is what made them stand up and shout.

This book, at root, is about the core of that ninety percent of our feeling which we all share. It is about a more realistic conception of the world and of the universe which comes into existence—and can come into existence—only when we acknowledge that to a very large degree we are all the same.

I should perhaps say a brief word about my claim that these four books are “an essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe.” In the course of explaining my views on architecture, and what it takes to make a coherent architecture, I have proposed models that include two features which would be large enough to justify the claim that these books are about the nature of the universe.

One of these is the claim that all space and matter, organic or inorganic, has some degree of life in it, and that matter/space is more alive or less alive according to its structure and arrangement. This claim is discussed in the present volume, Book I, THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE. The other is the claim that all matter/space has some degree of “self” in it, and that this self, or anyway some aspect of the personal, is something which infuses all matter/space, and everything we know as matter but now think to be mechanical. This claim is discussed in Book 4, THE LUMINOUS GROUND.

If either of these claims comes, in future, to be considered true, that would radically change our picture of the universe. Indeed, one might then say that the universe as we have known it for the last four hundred years, even in the exciting and fascinating versions of physics and cosmology which have come under discussion in recent decades, would then have to be replaced by a fundamentally different and more personal view of matter.

PREFACE

1 / OUR CONFUSION IN ARCHITECTURE

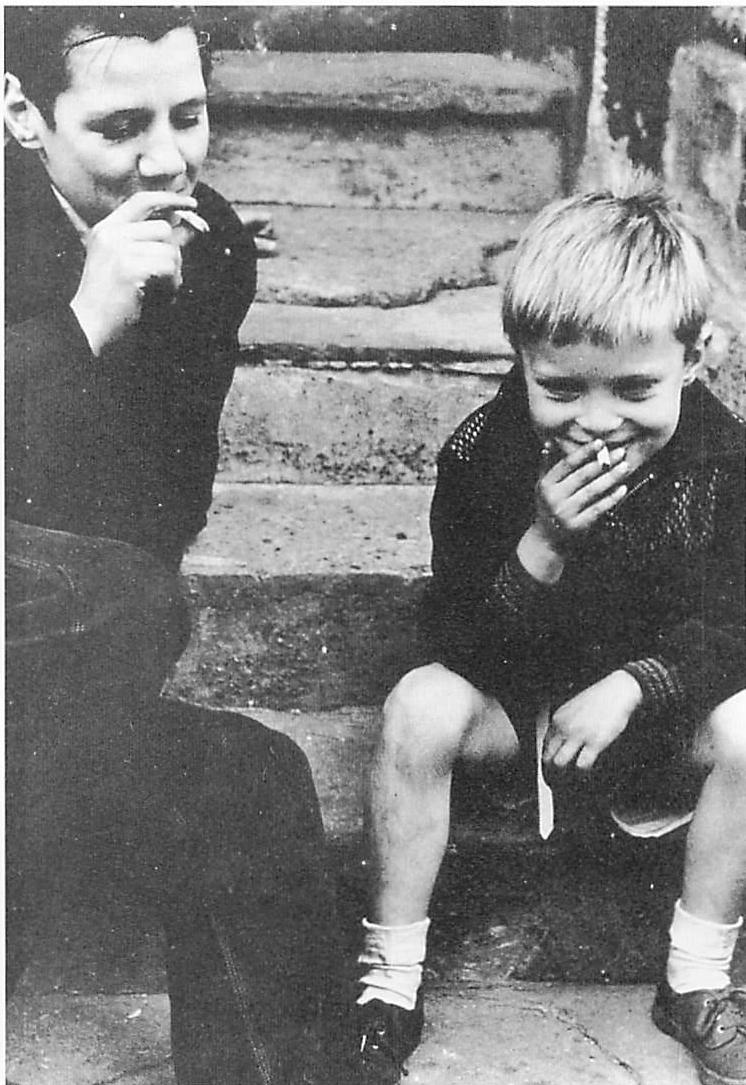

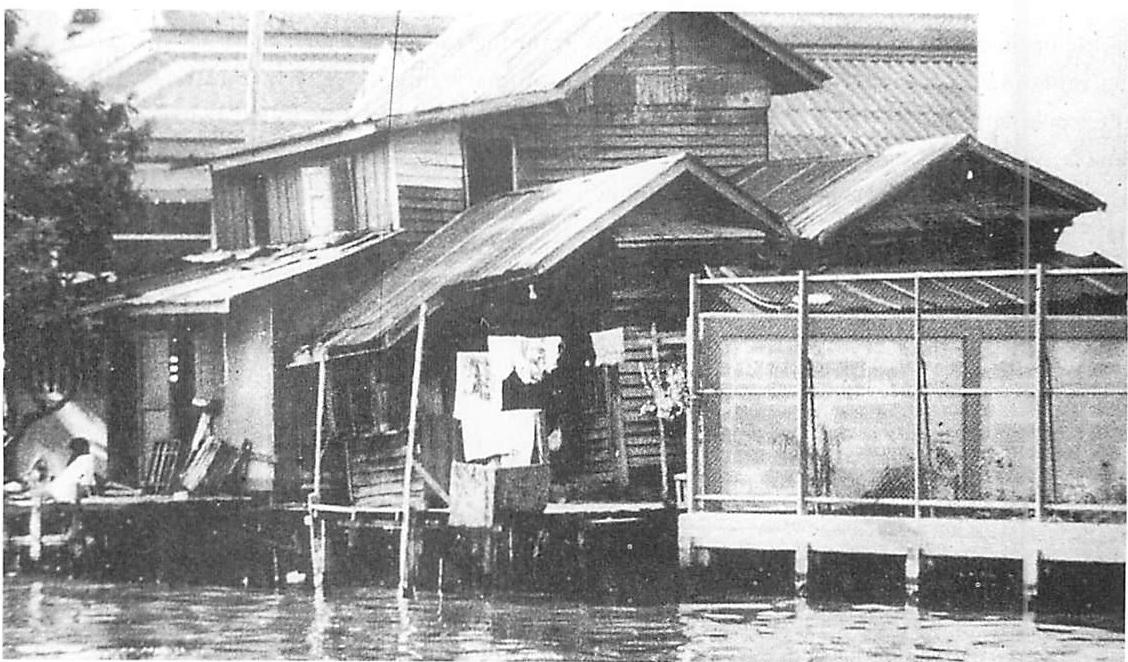

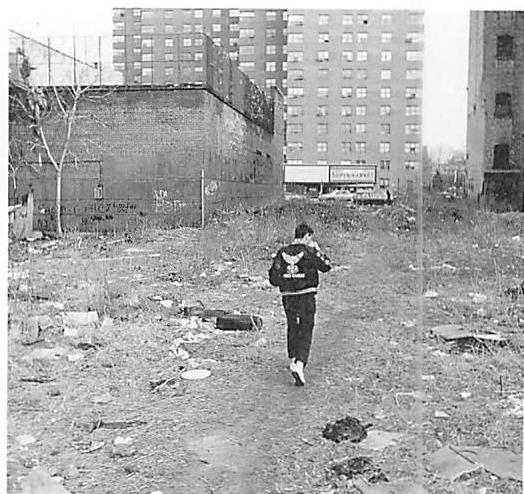

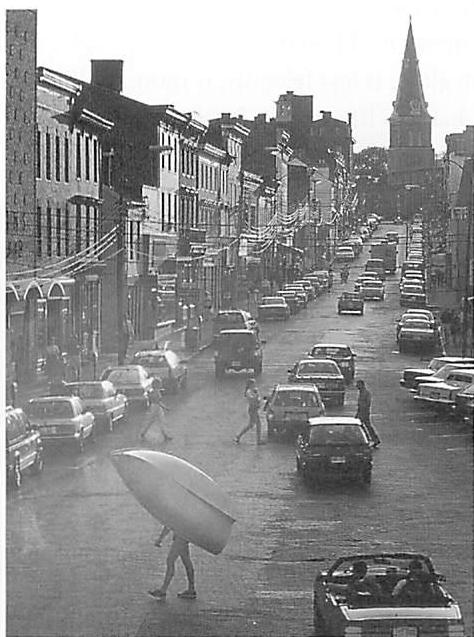

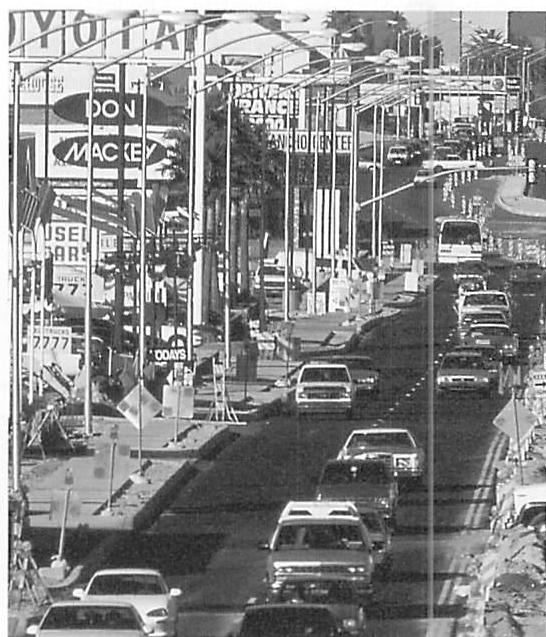

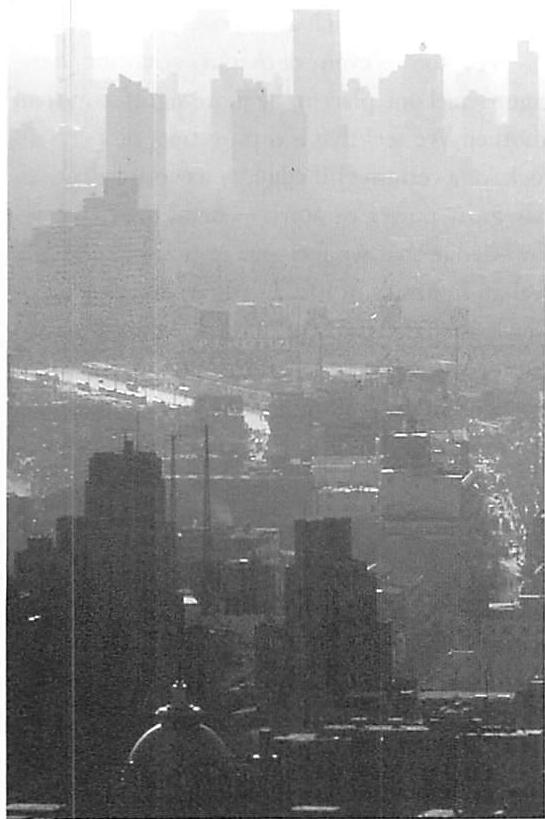

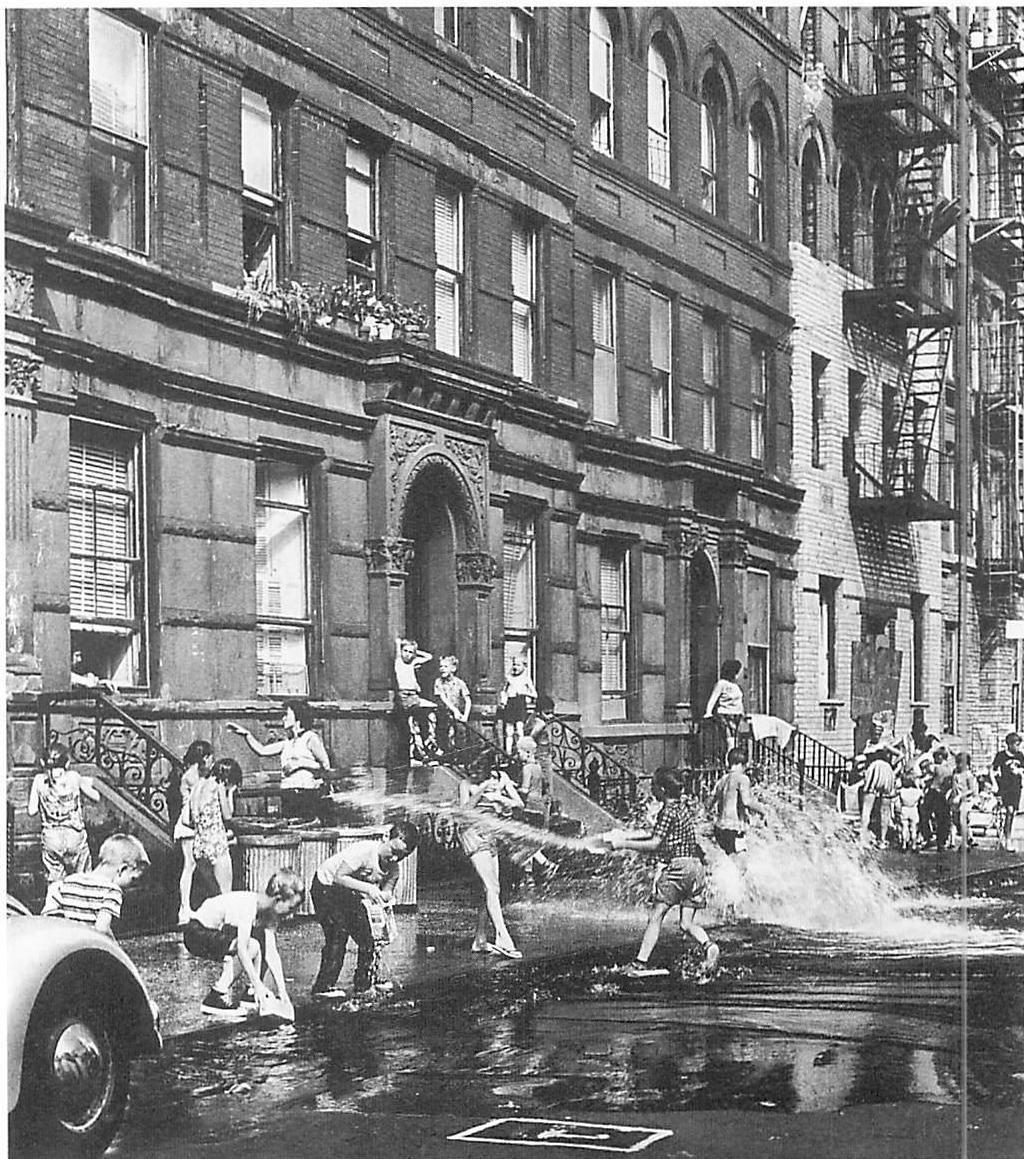

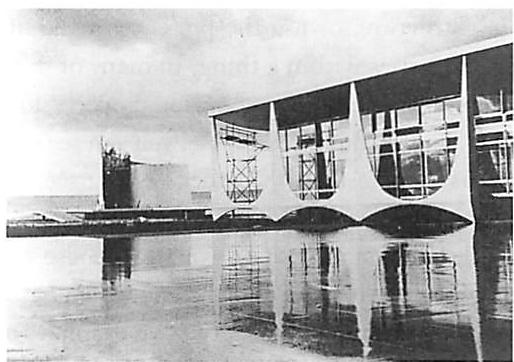

In the 20th century we have passed through a unique period, one in which architecture as a discipline has been in a state that is almost unimaginably bad. Sometimes I think of it as a mass psychosis of unprecedented dimension, in which the people of earth—in large numbers and in almost all contemporary societies—have created a form of architecture which is against life, insane, image-ridden, hollow. The ugliness which has been created in the cities of the world, and the banality and pretentiousness of many 20th-century buildings, streets, and parking lots have overwhelmed the earth. Much of this construction is caused by developers, housing authorities, owners of hotels, motels, airport authorities. In that sense architects might be considered blameless, since in some degree the ugliness of what has been created is caused by new relations between time, money, labor, and materials and by a set of conditions in which the real thing—authentic architecture that has deep feeling and true worth—is almost impossible.

But architects are not blameless. For the most part, architects have stood by, content to play their role as part of the 20th-century machine. In many cases they make it worse. They gild the lily of commercial development with pretentiousness. Many architects have raised the designer-conscious fashion of building to new levels, have invented absurd ways of thinking about architecture, have altogether poisoned the earth with an abundance of terrible and senseless designs which have few redeeming features.

Of course there are many architects who struggle to make socially useful architecture. Low-cost housing, shelters for homeless people, communities and pedestrian neighborhoods, better apartment buildings, offices set in green landscapes and parks. But somehow these, too, often fail to hit the mark. The intellectual satisfaction of these sincere goals is rarely matched by a true feeling of value achieved, of buildings, streets, and neighborhoods which are nourishing and which act as fitting vehicles for our sacred human life.

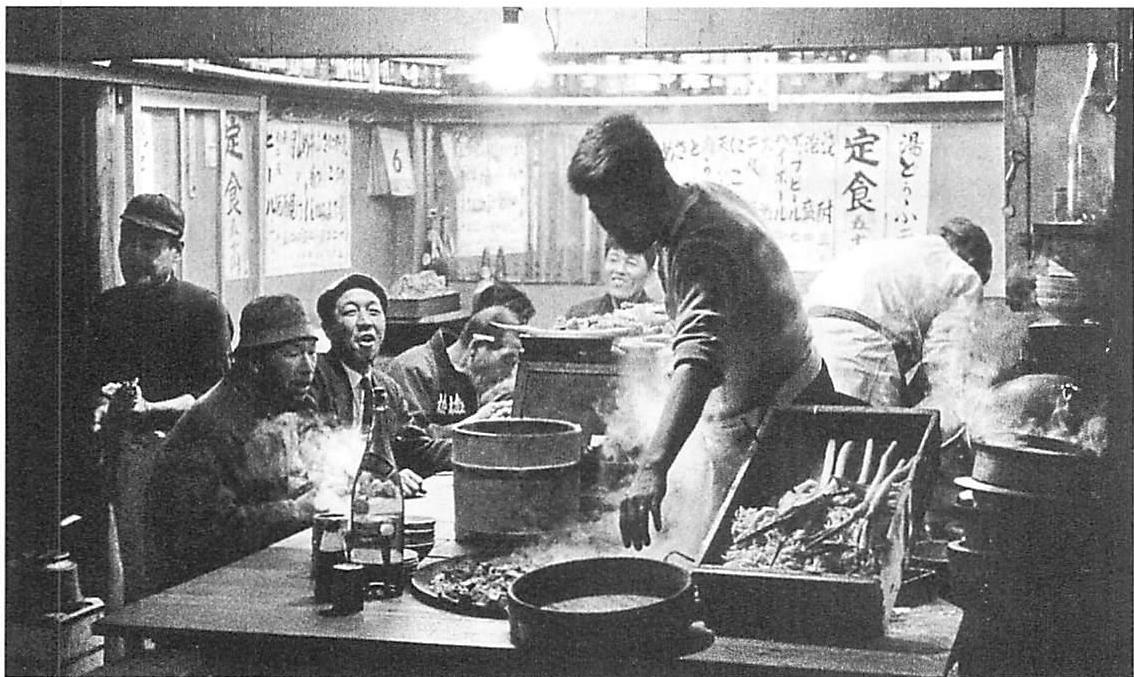

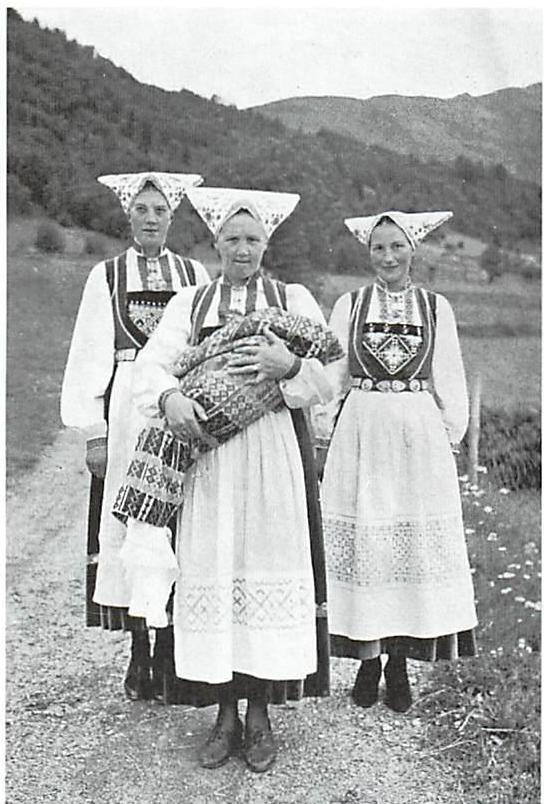

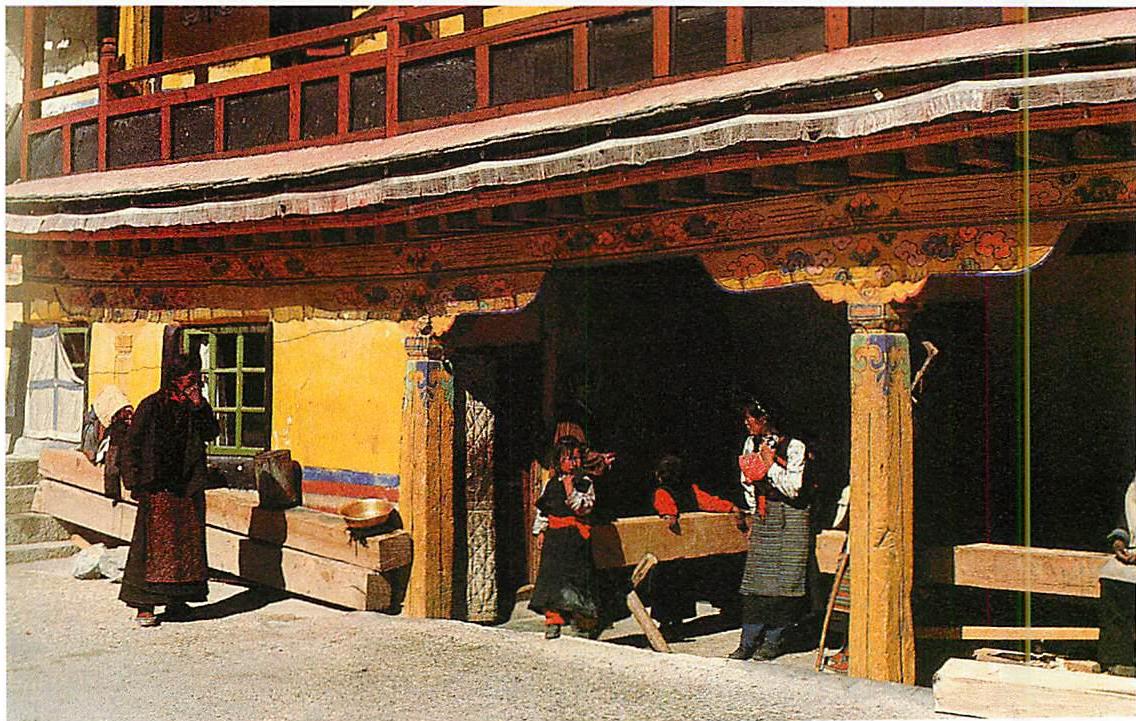

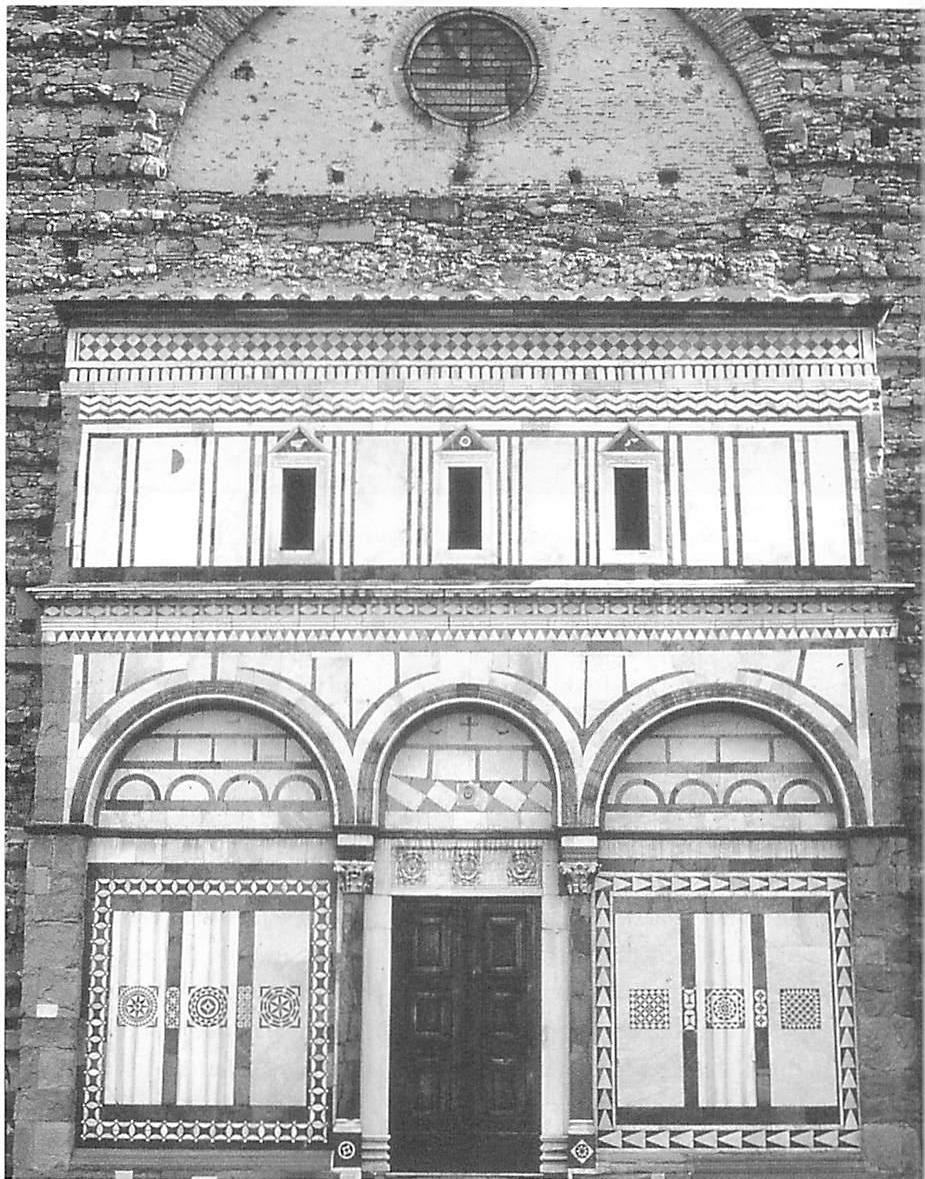

In traditional society, building was almost always something that stood for human value, that raised life to its greatest possible heights, that supported a spiritual and meaningful conception of human existence.

Now, instead, too many architects rub their hands cynically, foisting images on the public, creating works which are not friendly to people, or to the human spirit, but are friendly to the developers who make huge profits from these buildings and which do much to bolster those architects with financially rewarding glossy images in magazines.

Of course architects, like others, have a conscience. Many of us regret the situation. Many struggle, like drowning men and women, in the sea that engulfs us. Some of us, though, do not know what to do. We must eat, we cannot afford to lose our jobs. The conditions which create the inhumane architecture that is being produced cannot be too closely scrutinized, since too close a scrutiny can lead to uncomfortable questions, which may ultimately make us unemployable. So, in one form or another, we — all of us, architects, builders, planners, and financiers, who have taken part in the construction of the modern environment — have participated, willy-nilly, and for the most part with little more than mild objection to this robbing of the earth.

That is what I mean by a mass psychosis. Has there ever been a time in the history of the earth when a group of people, entrusted by society with the creation and preservation of our physical world, have so sadly undermined it, become collaborators with the enemy—when the enemy is, even, unknown to many of us? Is there even an enemy at all? Yet we have, many of us, parlayed our own profession to a new con-

dition in which it not only follows this madness, but even leads others on, continues it, protects it, enlarges it.

I do not think architects are happy with all of this, any more than other members of society are happy. In the last two decades voices have begun to be heard. People have written, spoken out. Away with the emperor's new clothes! We can all see that he is naked. Let us not go on with these charades.

What is it that has to be done? How should an architect who feels that things are wrong set them right? Many of us know that something is wrong, and yet do not know, concretely, how to act to correct the wrong. How is it possible to improve the situation, when the process that causes so much destruction is so deeply rooted in society that it is almost impossible for one architect, or even a hundred architects, to stand up against it and have any positive effect?

2 / HOW ARCHITECTURE DEPENDS ON OUR PICTURE OF THE WORLD

Very few people realize, I think, how much the present confusion which exists in the field of architecture is wound up with our conception of the universe.

I have come to believe that architecture is so agonizingly disturbed because we—the architects of our time—are struggling with a conception of the world, a world-picture, that essentially makes it impossible to make buildings well. I believe this problem goes so deep that it even makes it extremely difficult to build the most modest, useful building in an ordinary way.

Many of us are not especially aware that our conception of things—our picture of the universe—could have any concrete or immediate effect on our activity as architects. We go about our business trying our best to make good buildings—in whatever fashion we understand "good." The task is difficult. We struggle with it. But we are not aware, I think, that our effort is affected in any substantial way by the picture we have of things, the picture we have of the world. Most of us are not even aware, perhaps, that we have any special picture of the world.

And, if we do ever carefully examine our own picture of the world, we shall find, no doubt, a rather complicated mixture of things: vague conceptions of atoms, galaxies, and stars; organic life as it appears on earth from, we are told, some primordial soup of amino acids. Mixed with this, there is no doubt some form of concern for our fellow human beings, some kind of piety, some awareness that certain things are more beautiful and others less. How can all this muddled mess of a conception of the world be responsible for anything?

How could it possibly be true that this conception might interfere so deeply with our efforts as builders, that it makes it all but impossible to make a building well?

The implication seems fantastic. And yet this is just what I believe. I believe that we have in us a residue of a world-picture which is essentially mechanical in nature—what we might call the mechanist-rationalist world-picture. Whether or not we believe that we are subscribing to this picture, whether or not we are aware of the impact of its residue in us, even when we consider ourselves moved by spiritual or ecological concerns, most of us are still—I believe—to a greater or lesser extent in the grip of some residue of this mechanical world-picture. Like an infection it has entered us, it affects our actions, it affects our morals, it affects our sense of beauty. It controls the way we think when we try to make buildings and—in my view—it

has made the making of beautiful buildings all but impossible.

What exactly do I mean by the mechanistrationalist picture of the world? What I mean, roughly, is the 19th-century picture of physics. That is, a picture of a world made of atoms which whirl around in a mechanical fashion: a world in which it is assumed that all the universe is a blind mechanism, whirling on its way, under the impact of the "laws of nature." These laws are, essentially, those mechanistic laws which explain how the atoms and the structures made of these atoms proceed on their way, under the influence of forces and configurations. Coupled with this picture there is a larger picture of weather, climate, agriculture, animal life, society, economics, ecology, medicine, politics, administration, and even family life — all understood in a more or less mechanical fashion. Even though we would admit that the precise laws and mechanisms may not be known, we assume that underlying our ignorance there are some laws, not quite formulated, which do account for how things work, even in these everyday surroundings. Thus we carry forward a blithe and rather simple mental assurance that it is all created by the pushing and pulling of events, very much the way we also understand the pushing and pulling of 19th-century atoms.

Of course, there are relatively few people alive today who wholeheartedly believe that the world really is such a place. Physicists—especially the great physicists—have a more humble and wondering attitude about the nature of the universe. So do many non-scientists. Architects are, at least explicitly, rarely concerned with such a mechanistic picture. On the surface architects appear to be concerned with deeper questions—artistic and social questions—that are often more mysterious and more interesting.

However, in trying to probe the nature of the puzzle surrounding the collapse of architecture, I have slowly become convinced that many architects—especially those who have become

famous in recent years and whose work now forms the model for the work of younger architects—are in the grip of such a mechanistic conception, even if they do not know it. I have reached the conclusion that the strange fantasies, the private in-house language about architecture, the strange nature of 20th-century gallery art, deconstructionism, postmodernism, modernism, and a host of other "isms," all of which affect our physical world hugely, are created because of an entanglement between the nature of architecture, the practice of architecture, and the mechanical conception of the universe.

Thus, I believe that there is, at the root of our trouble in the sphere of art and architecture, a fundamental mistake caused by a certain conception of the nature of matter, the nature of the universe. More precisely, I believe that the mistake and confusion in our picture of the art of building has come from our conception of what matter is.

The present conception of matter, and the opposing one which I shall try to put in its place, may both be summarized by the nature of order. Our idea of matter is essentially governed by our idea of order. What matter is, is governed by our idea of how space can be arranged; and that in turn is governed by our idea of how orderly arrangement in space creates matter. So it is the nature of order which lies at the root of the problem of architecture. Hence the title of this book.

When we understand what order is, I believe we shall better understand what matter is and then what the universe itself is. But so long as we are—even unconsciously—prisoners of a too-simple mechanical picture of matter, it is inevitable, I am afraid, that we—and the architecture we create—must continue in the blind confusion which too many of us have experienced for more than half a century.

That is my effort in this book: to show how architecture can be made whole again, through a new picture of the nature of order, and through a new picture of the nature of matter itself.

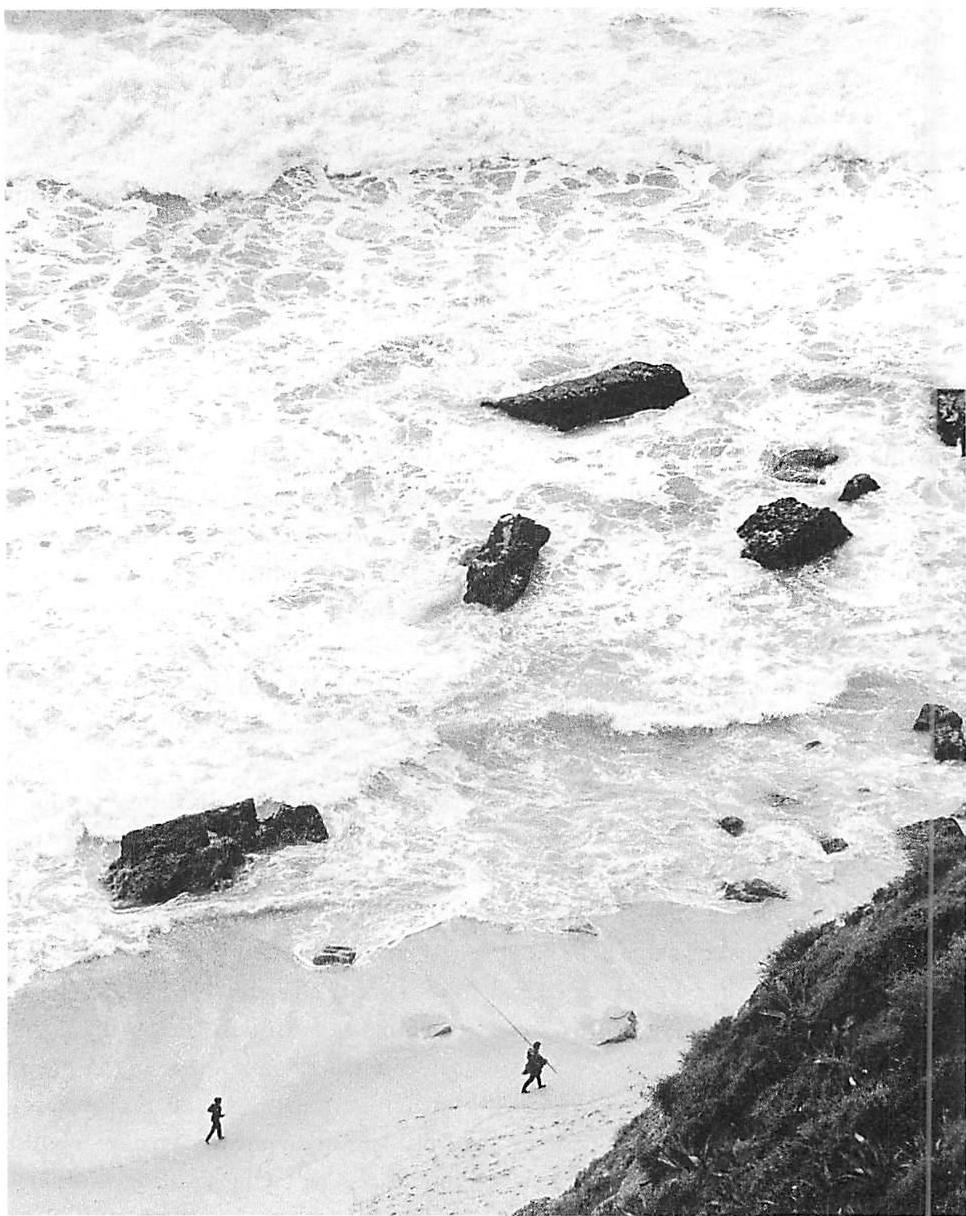

3 / WHAT IS ORDER?

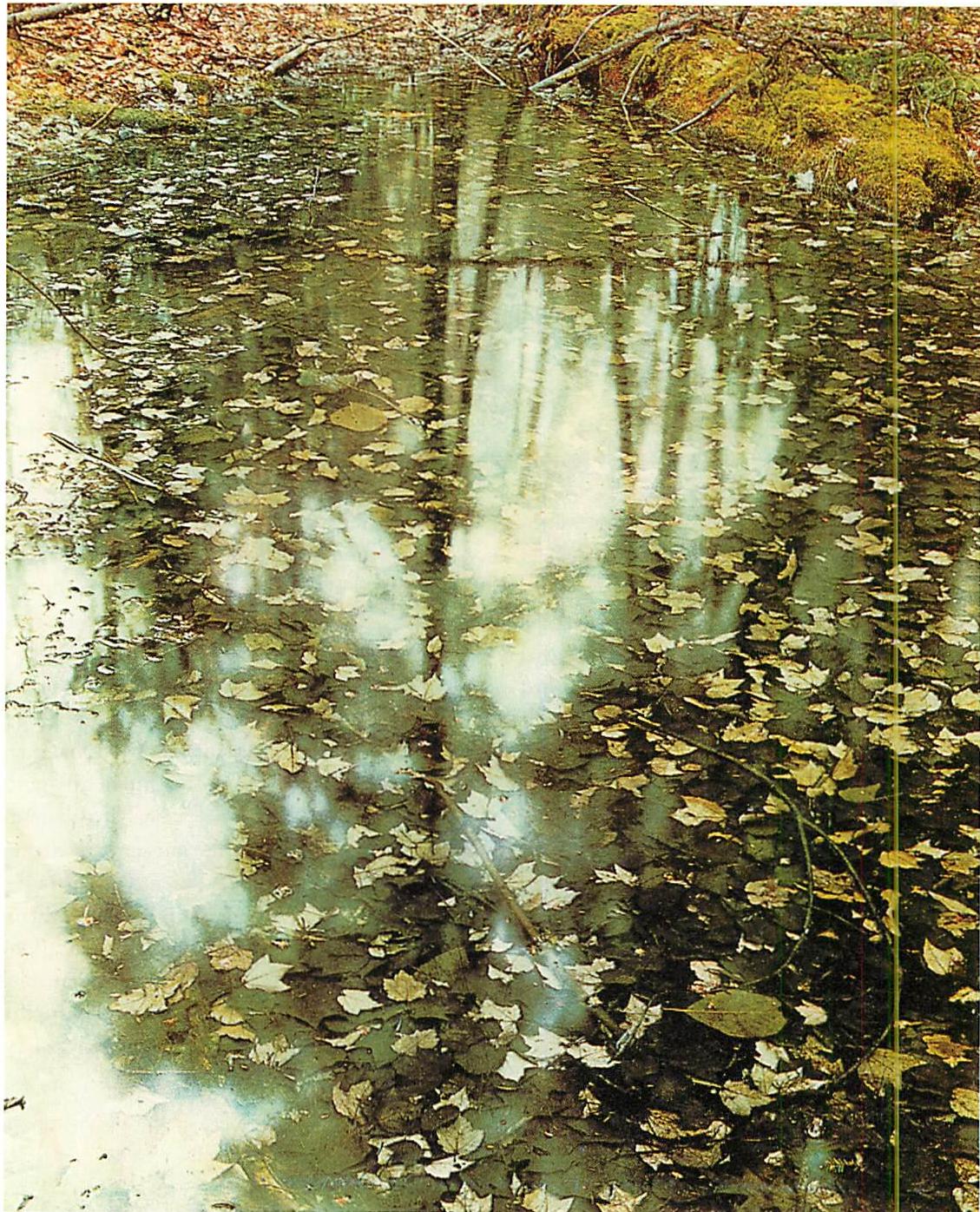

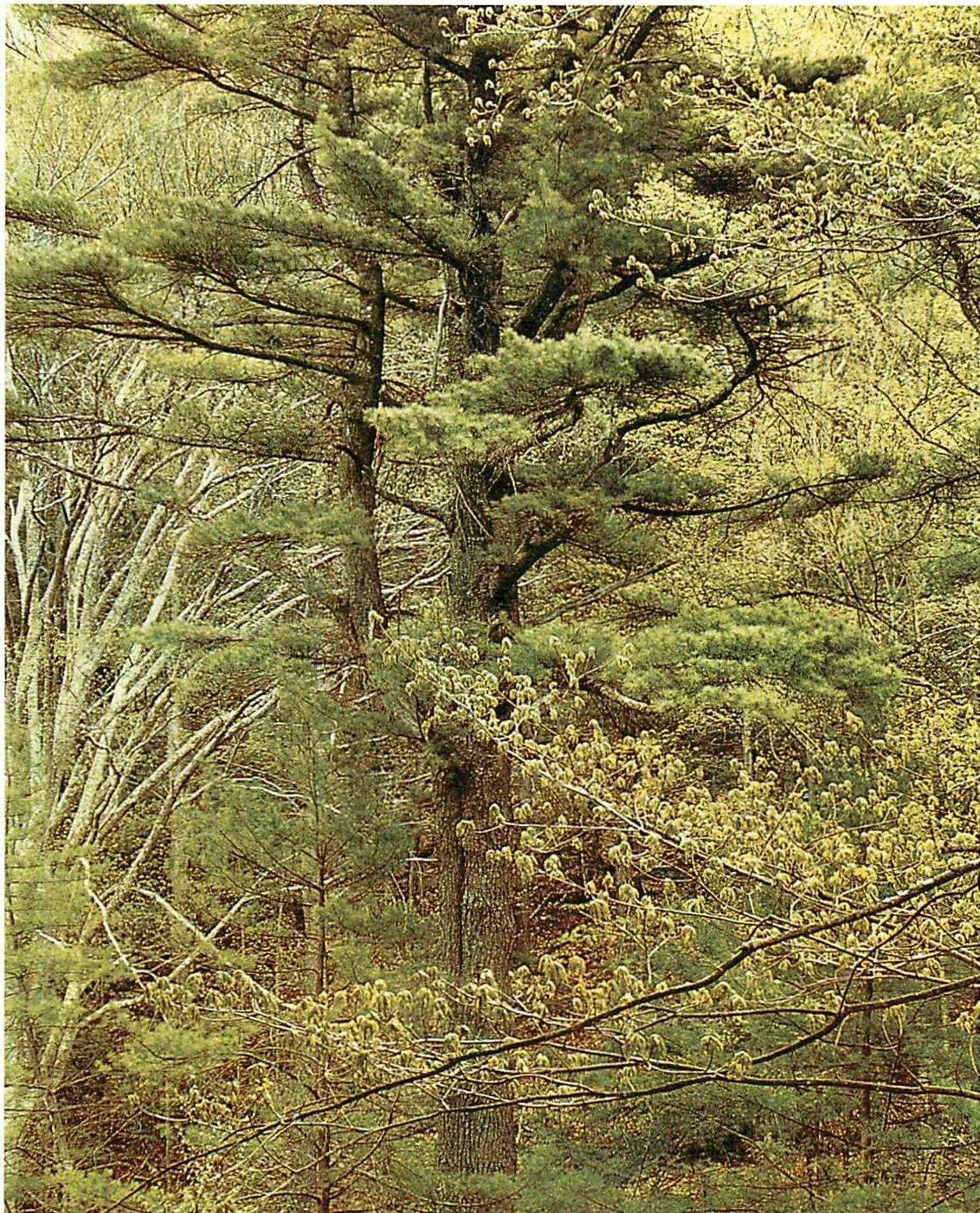

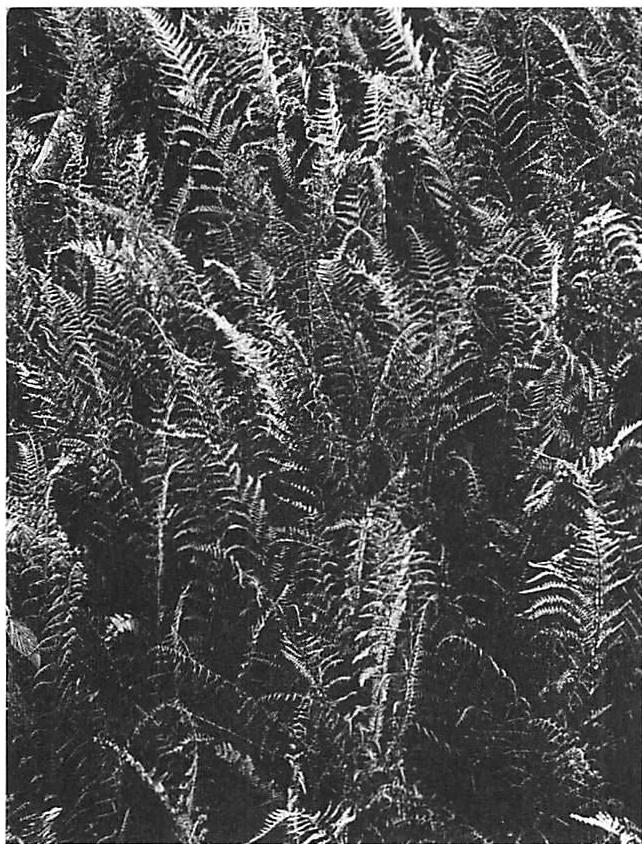

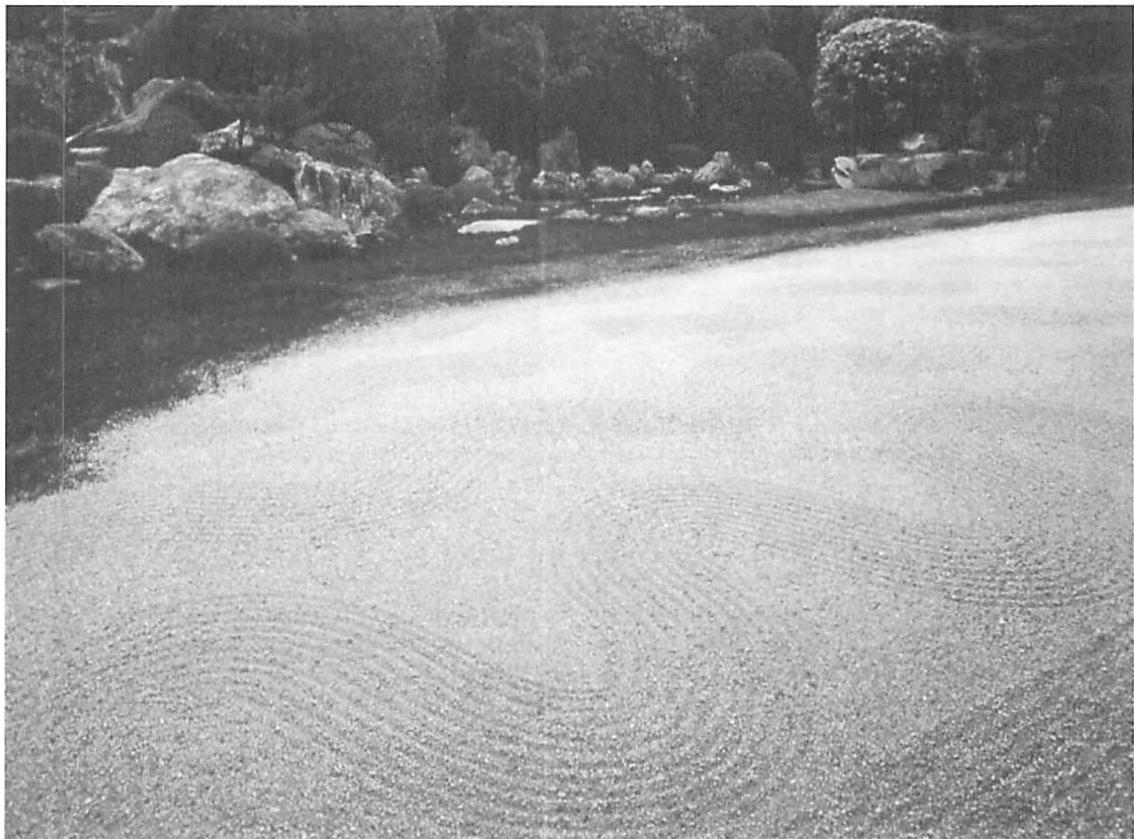

What is order? We know that everything in the world around us is governed by an immense orderliness. We experience order every time we take a walk. The grass, the sky, the leaves on the trees, the flowing water in the river, the windows in the houses along the street — all of it is immensely orderly. It is this order which makes us gasp when we take our walk. It is the changing arrangement of the sky, the clouds, the flowers, leaves, the faces around us, the dazzling geometrical coherence, together with its meaning in our minds. But this geometry which means so much, which makes us feel the presence of order so clearly — we do not have a language for it.

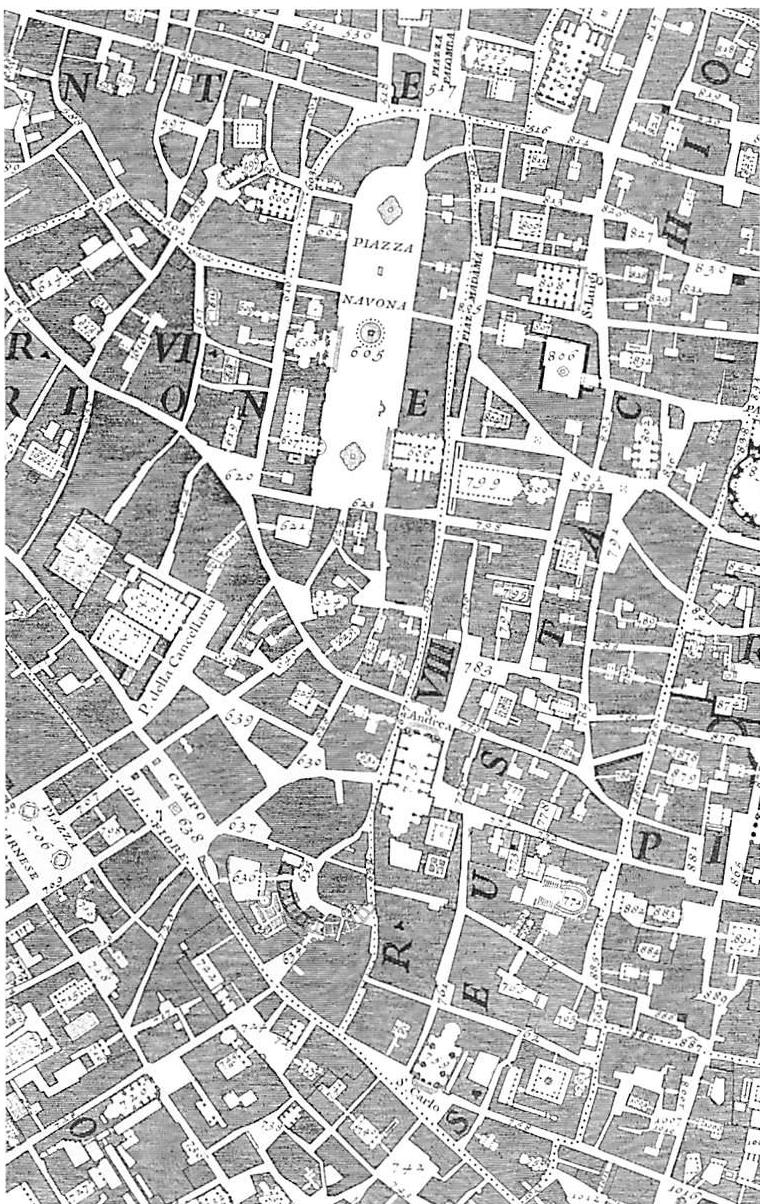

And what should we do to create order? Even the smallest building has order of great complexity. In the course of laying out and making the volume of the building, the filigree of structure, floors, windows, doors, and ornament — we face a dazzling task. What is the order we should infuse it with? In large projects, especially, we can easily get muddled. More is at stake, so the nature of the order we put in is especially crucial. We rely more on intellectual conceptions. So then, our assumptions about order begin to enter in explicitly. It is not only a single brick, or door, or roof. It might be a whole neighborhood — millions of dollars of construc

tion — perhaps the living environment for hundreds of people at a time. How do I do this? What kind of order should it embody, to make sure it is a success?

In facing any one of these tasks, I come up against this question right away: What exactly do I mean by order? If I want to get an idea of order which is deep enough to be really helpful—helpful to me, helpful to my craftsmen, helpful to my students, helpful to my clients, helpful to my apprentices and my staff—I have to define exactly what I mean by order.

In a sense, everyone knows what order is. But when I really ask myself “what is order”—in the sense of deep geometric reality, deep enough so that I can use it, and so that it is able to help me create life in a building—then it turns out that this “order” is very difficult to define.

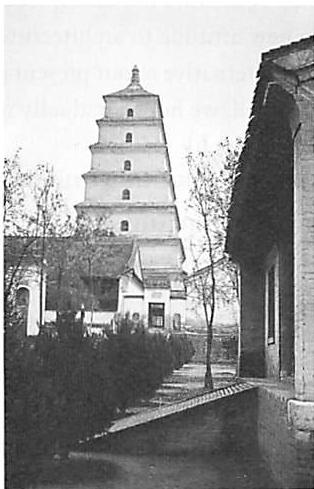

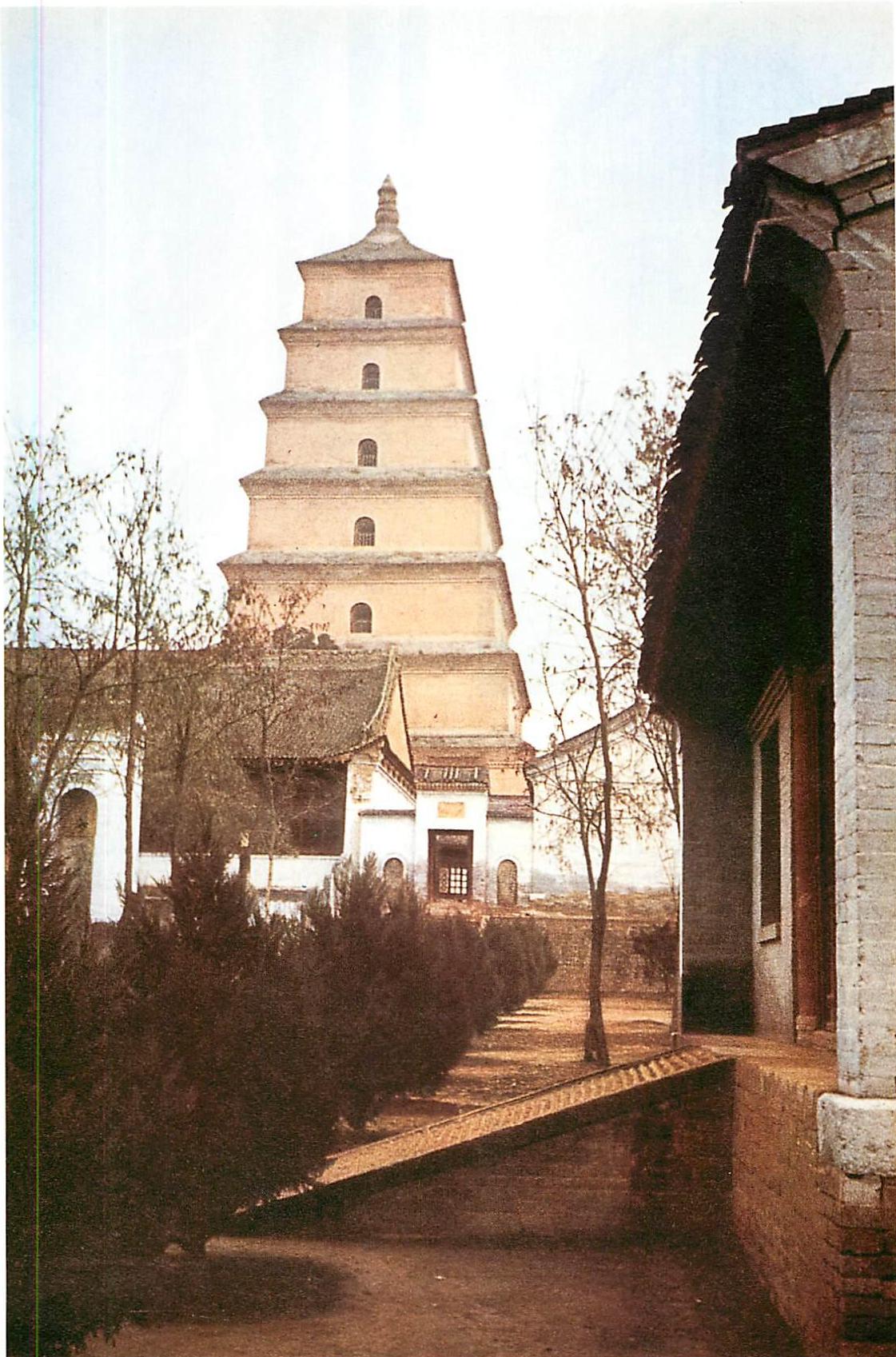

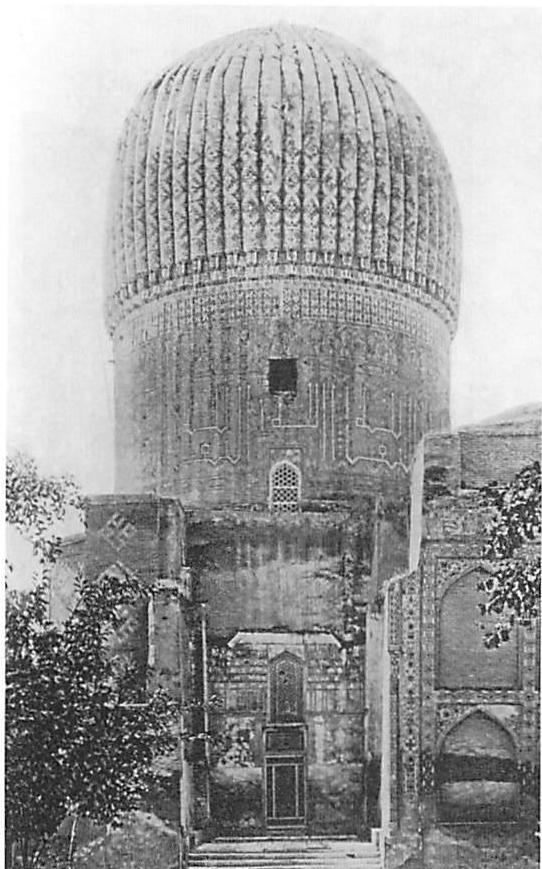

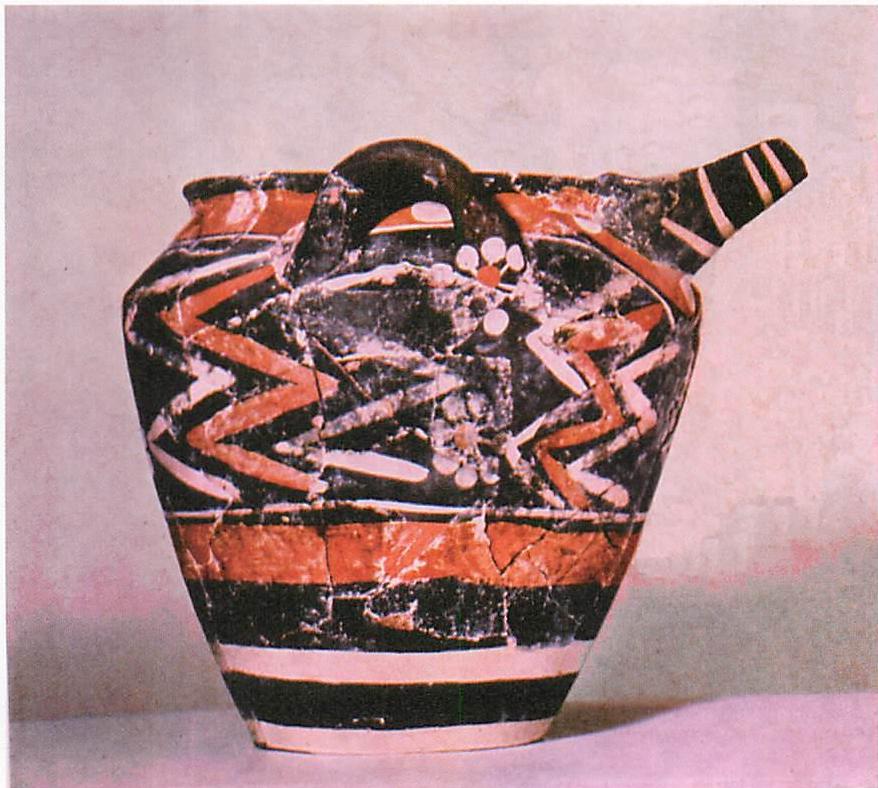

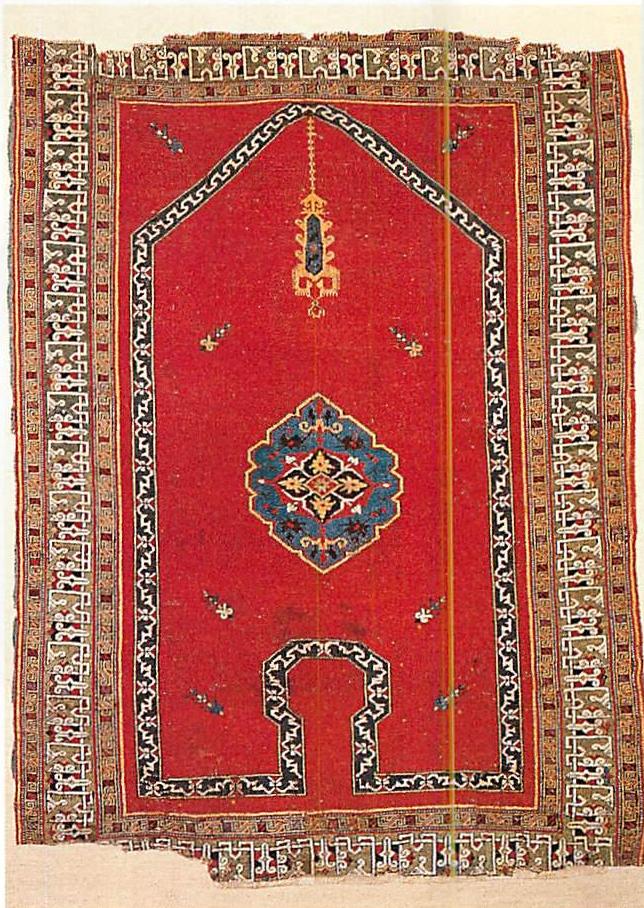

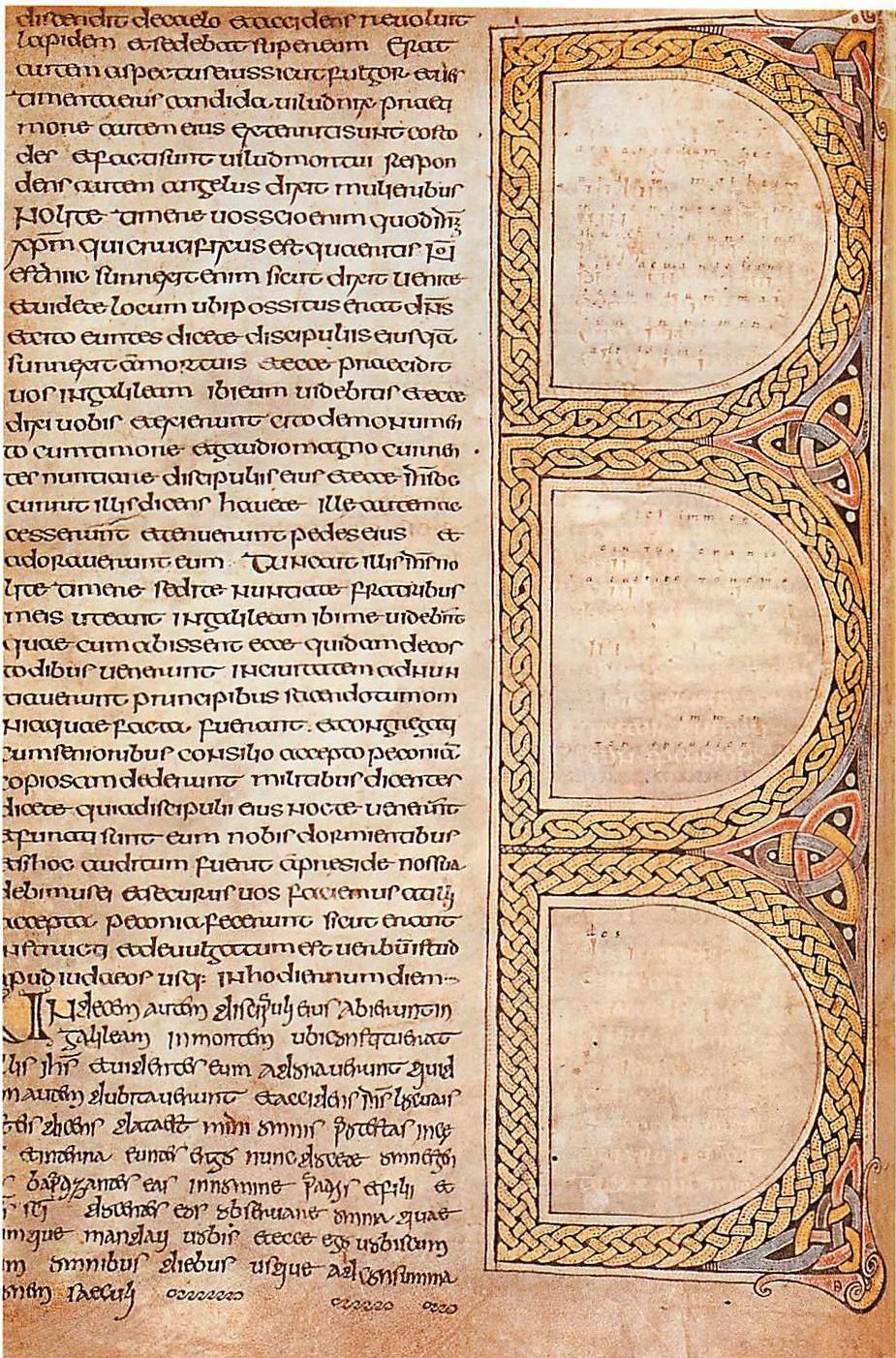

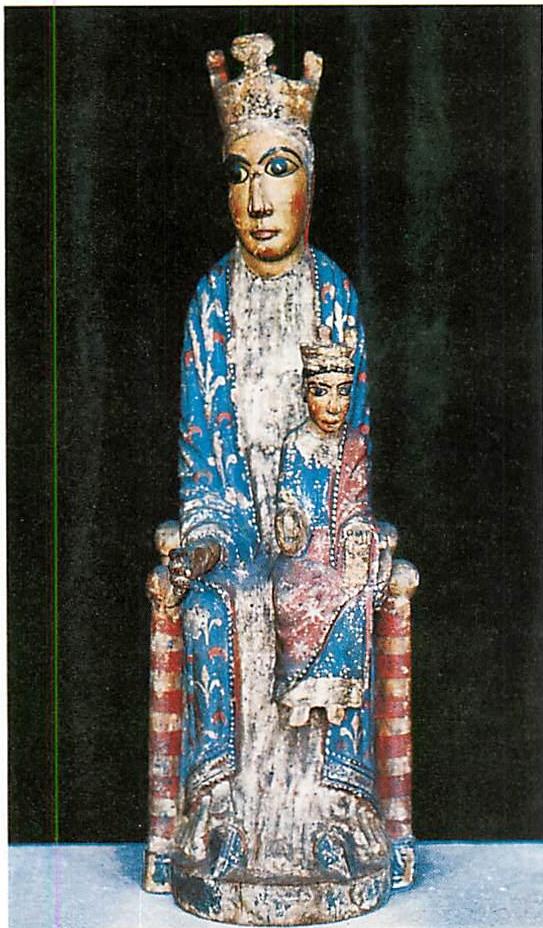

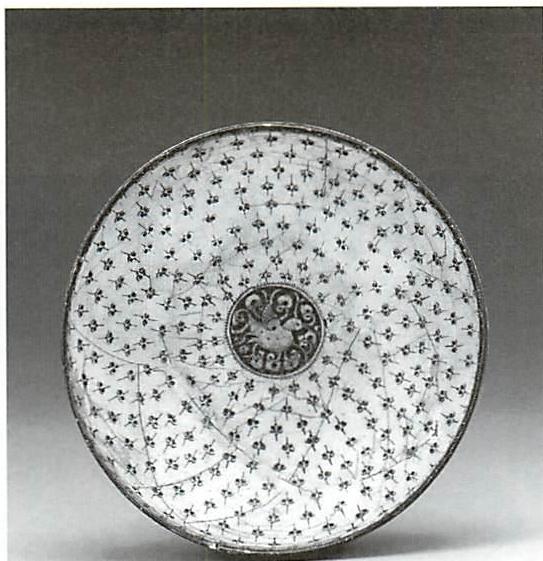

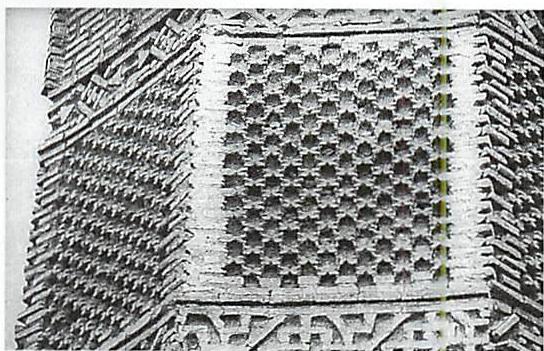

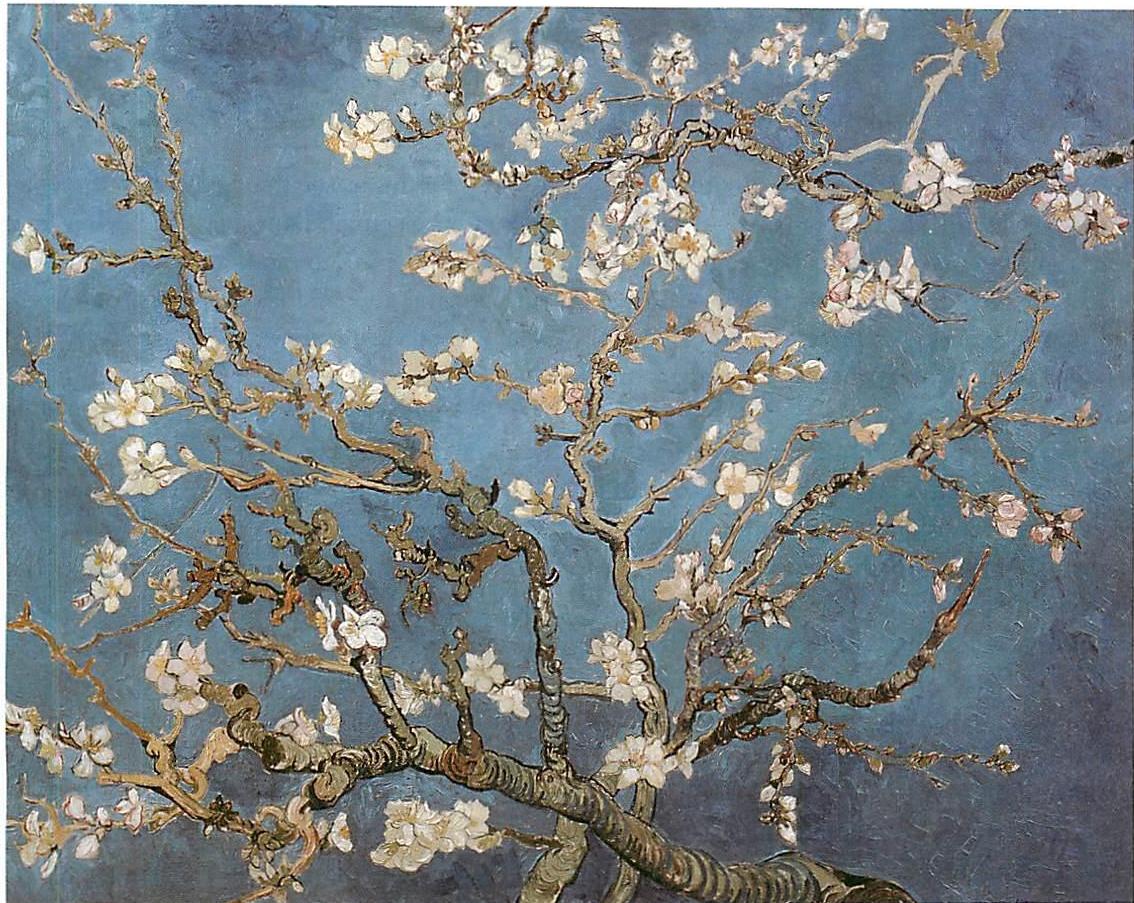

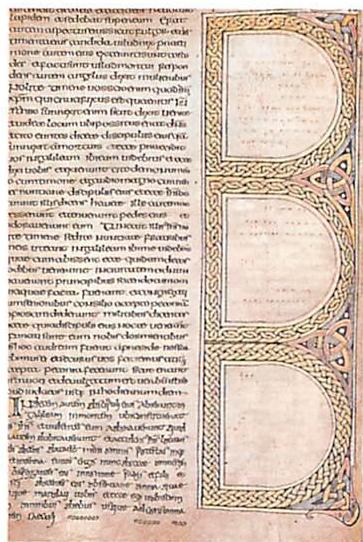

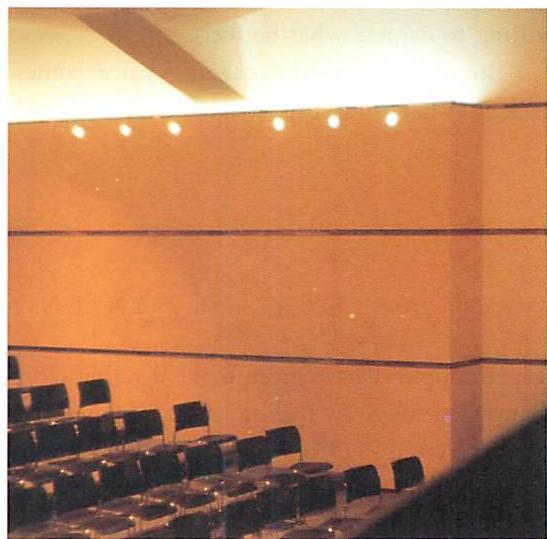

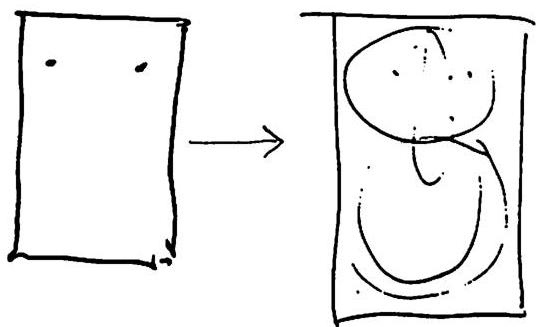

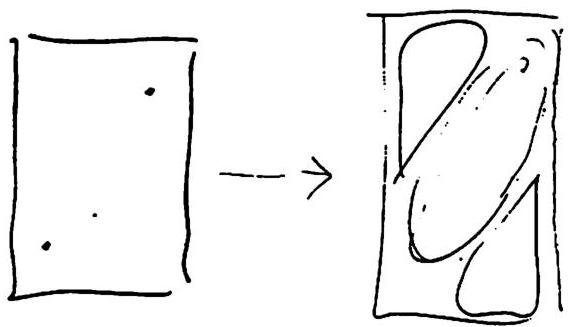

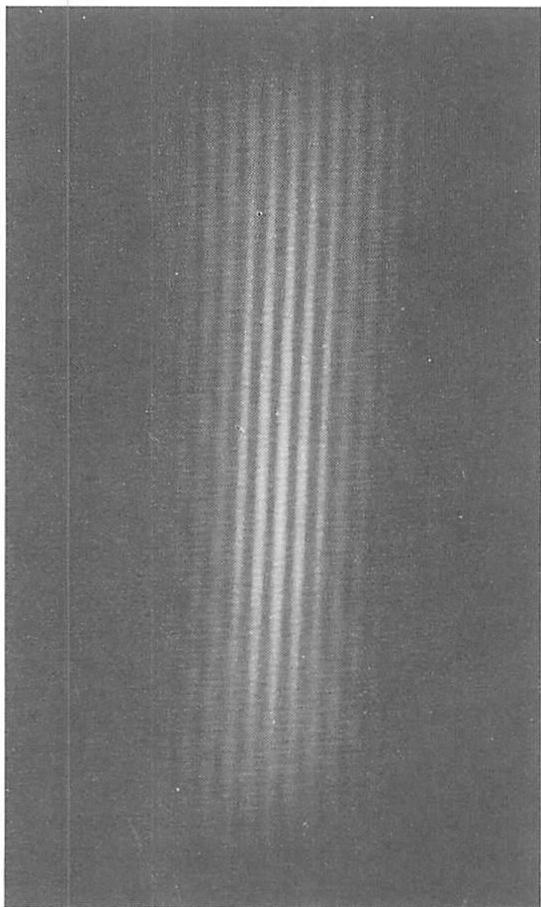

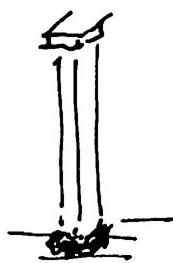

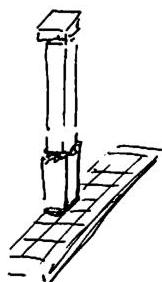

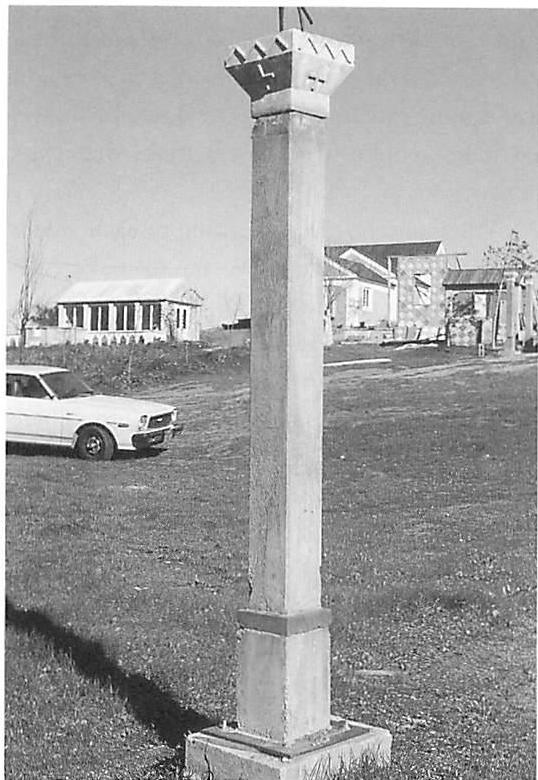

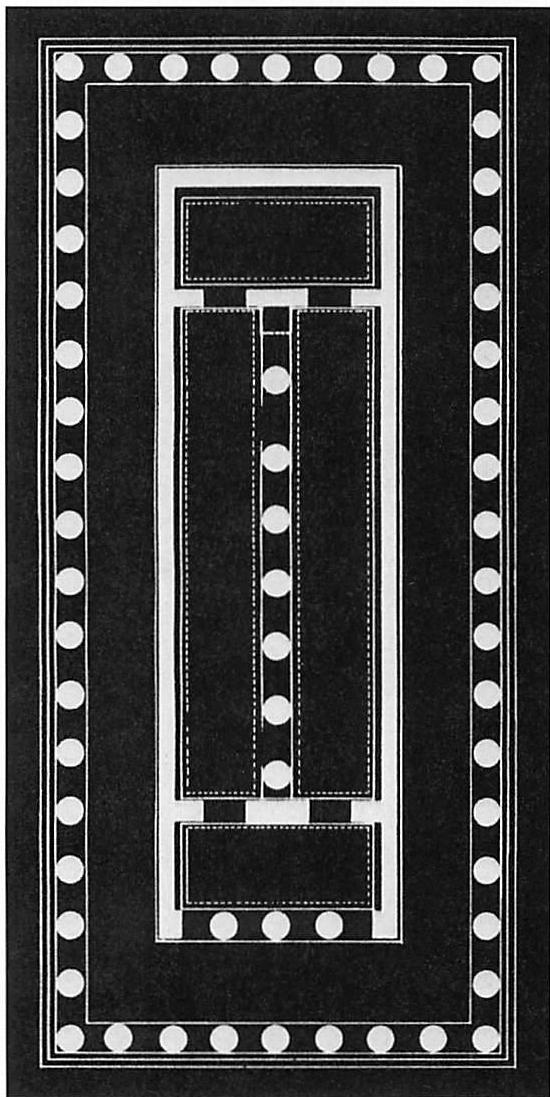

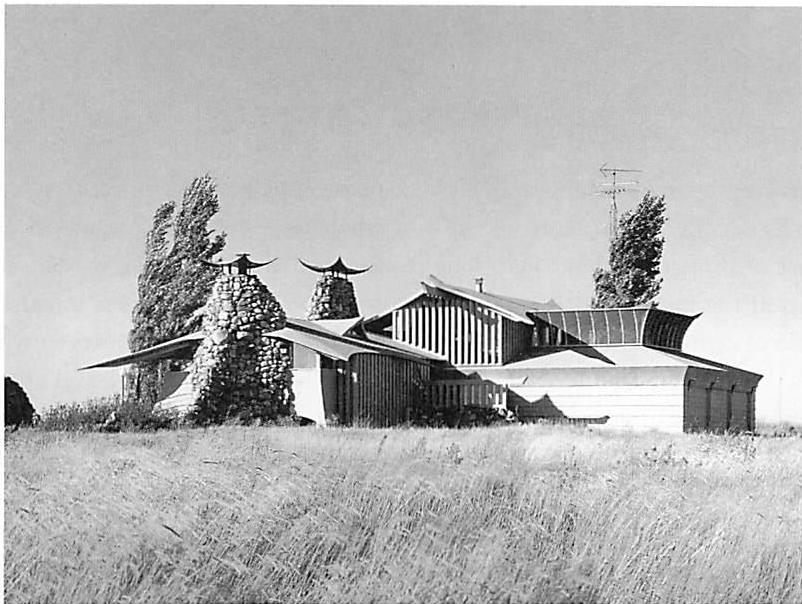

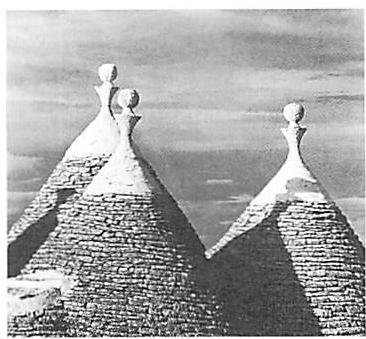

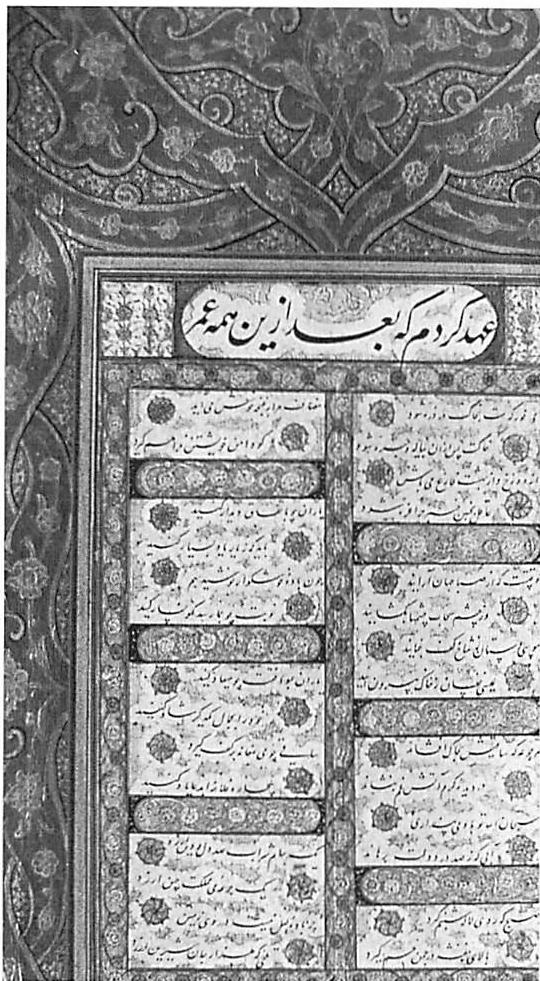

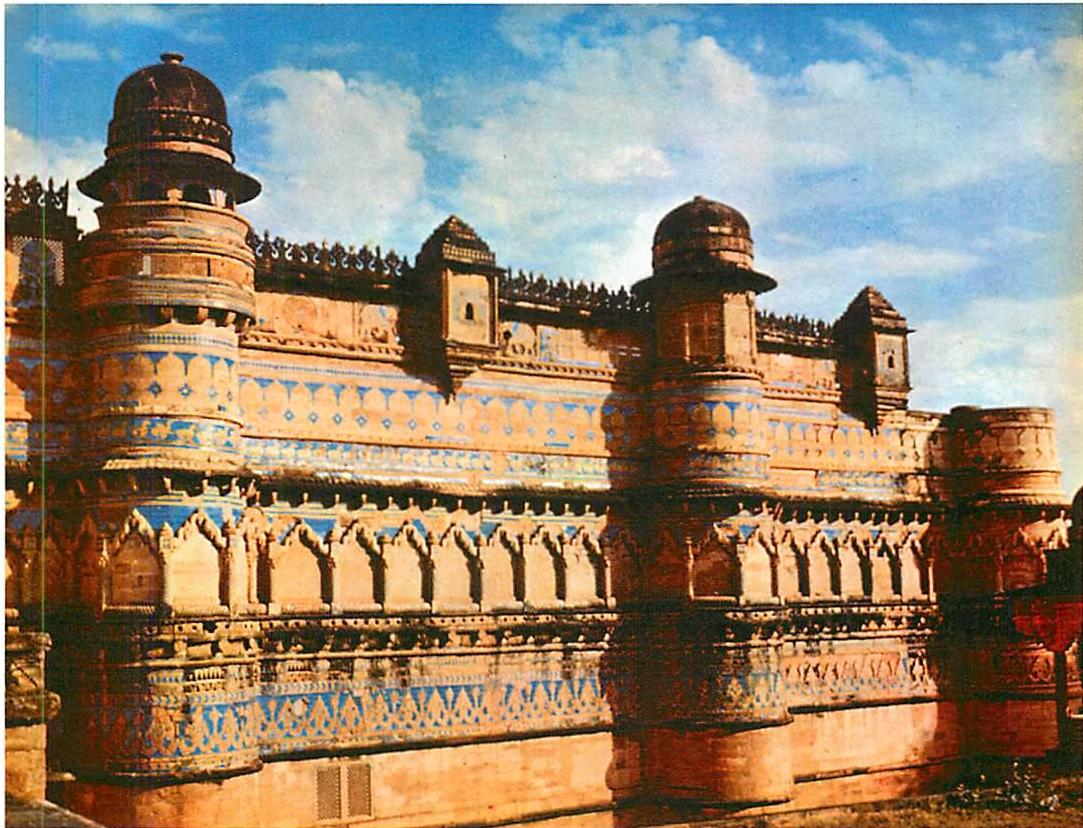

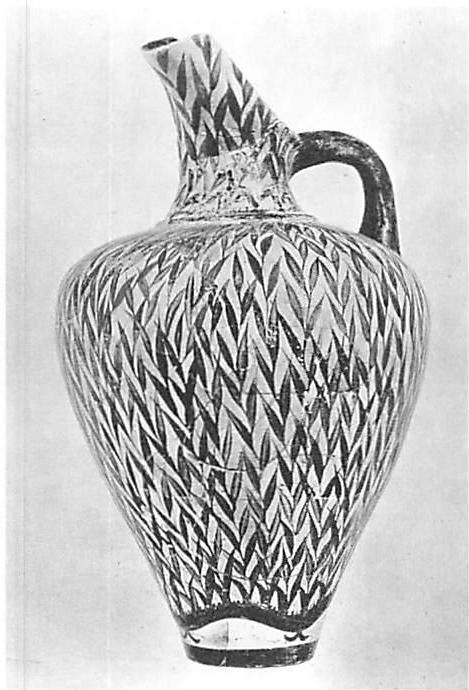

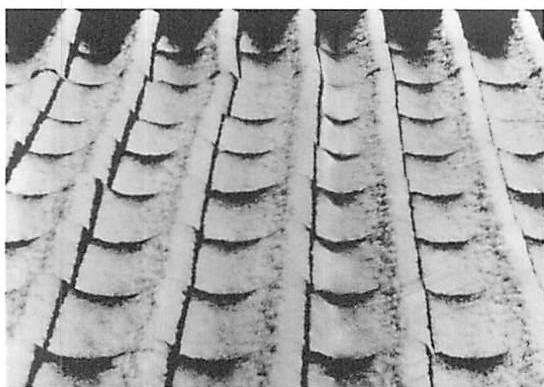

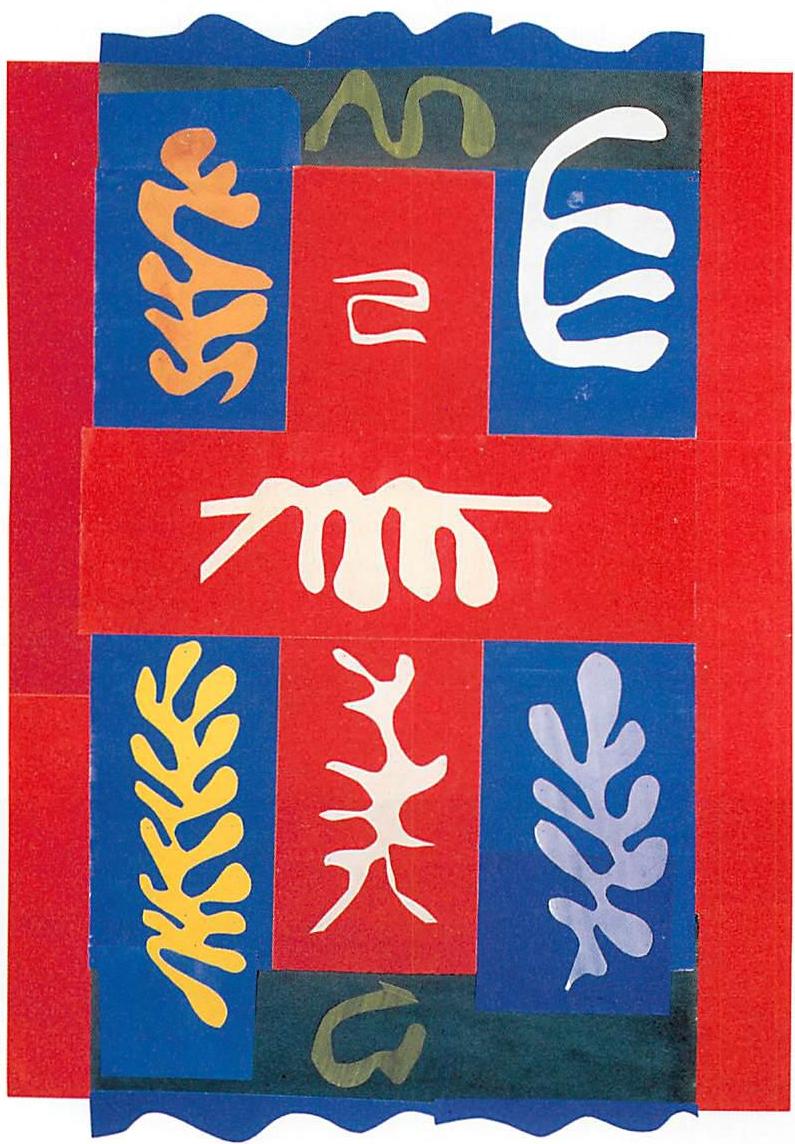

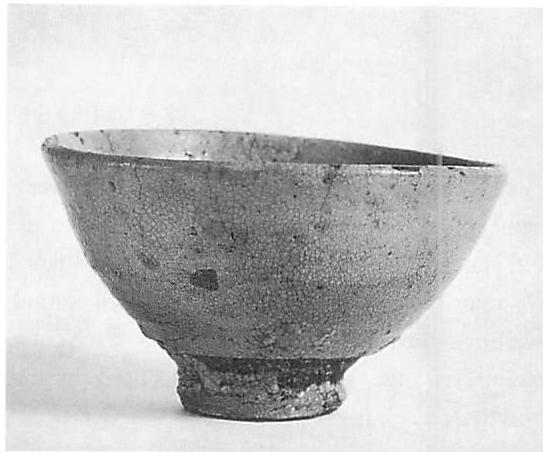

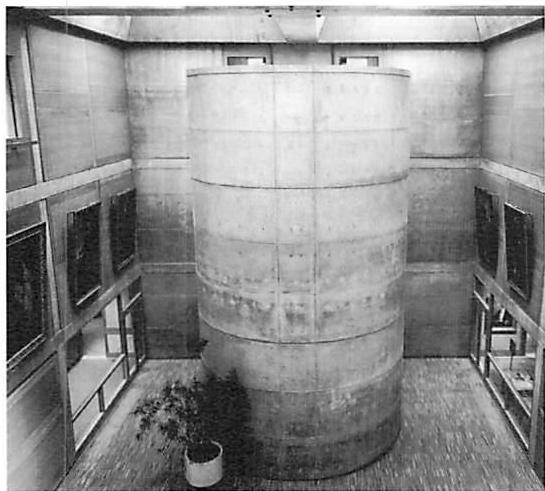

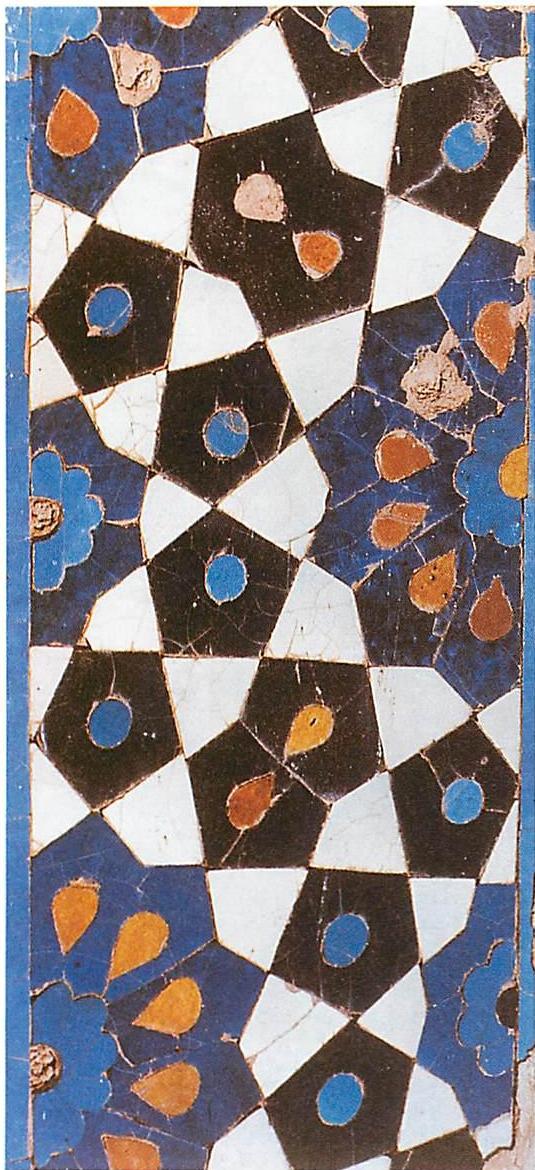

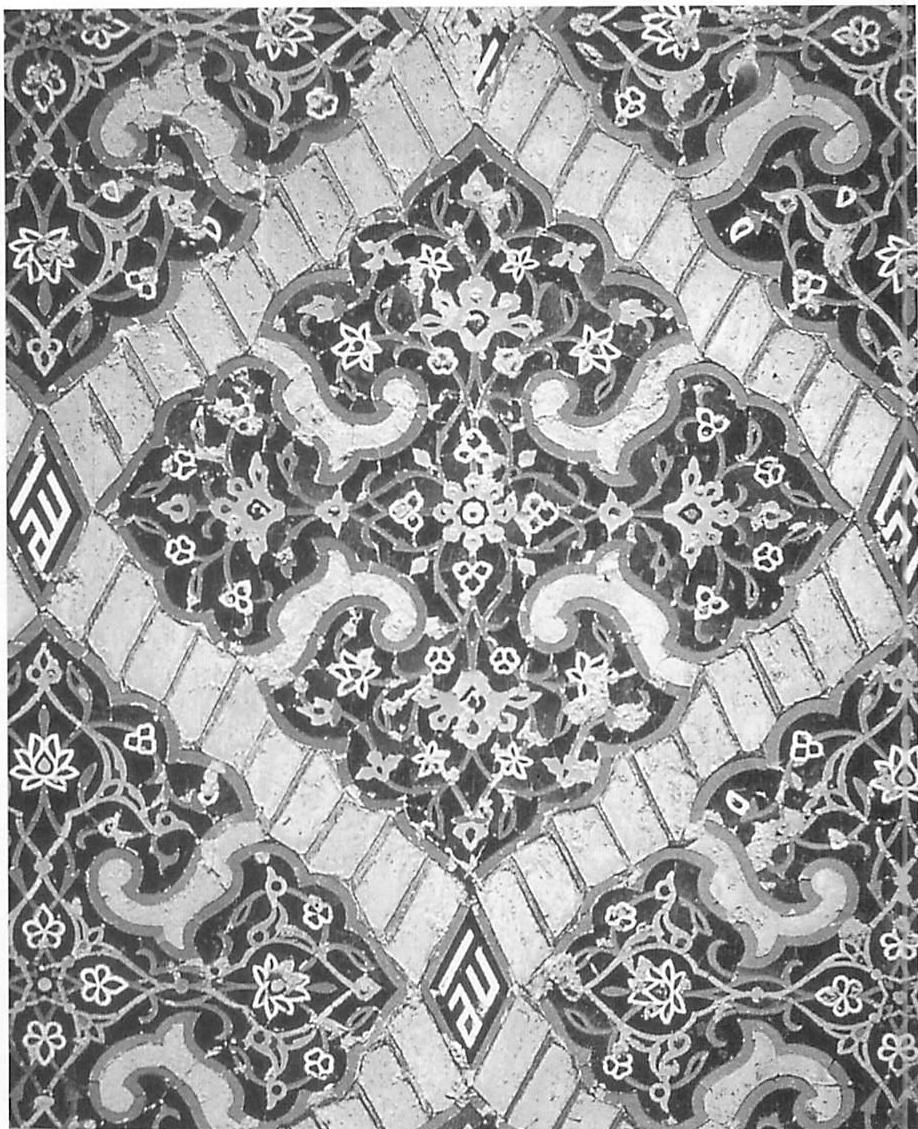

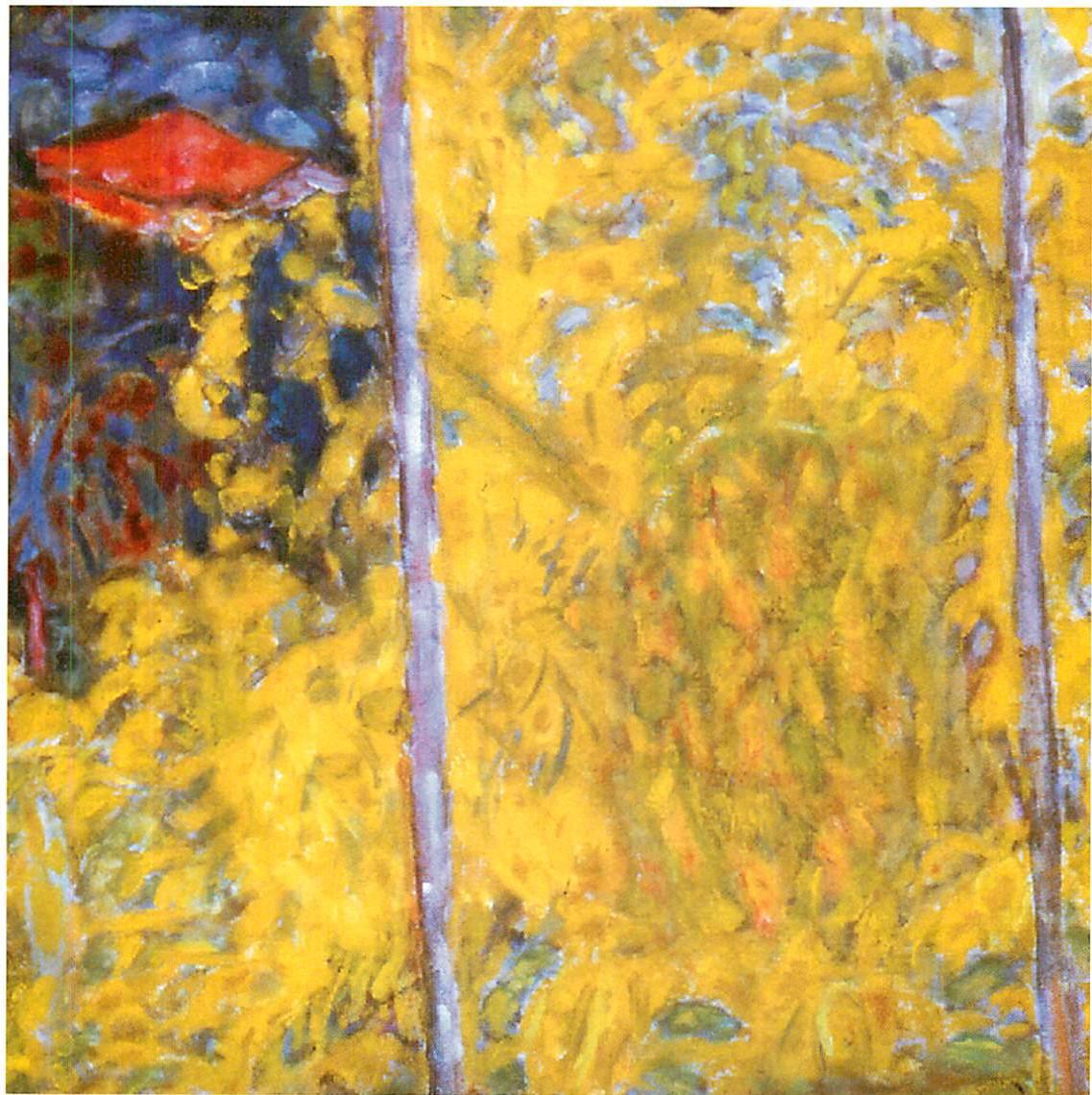

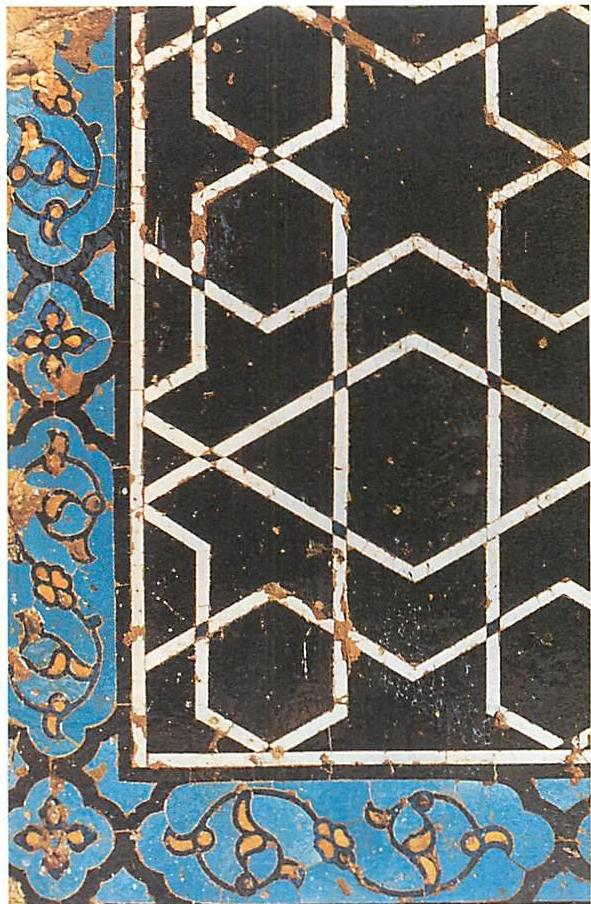

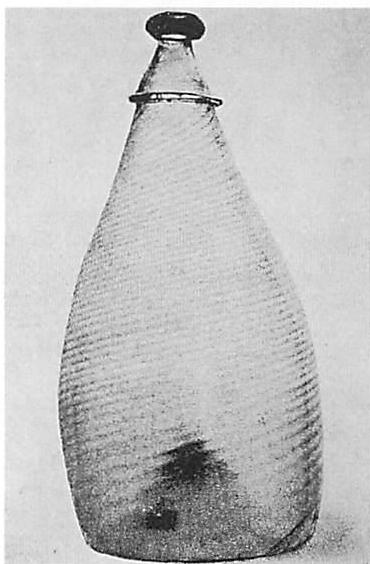

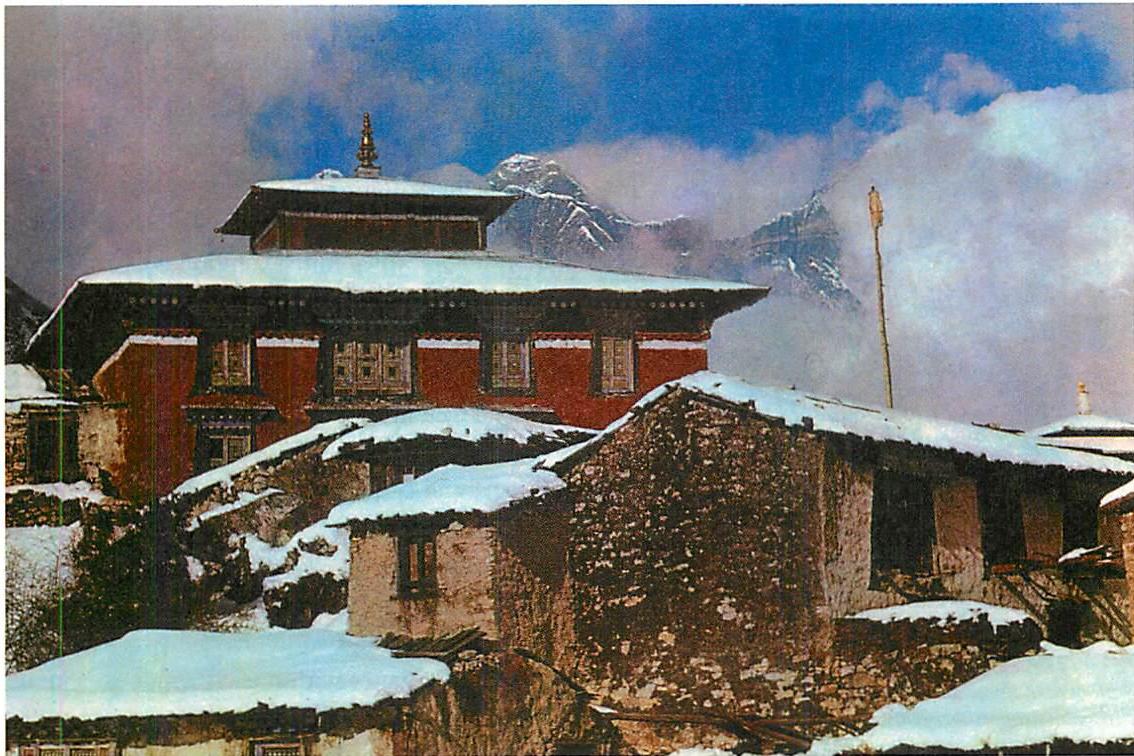

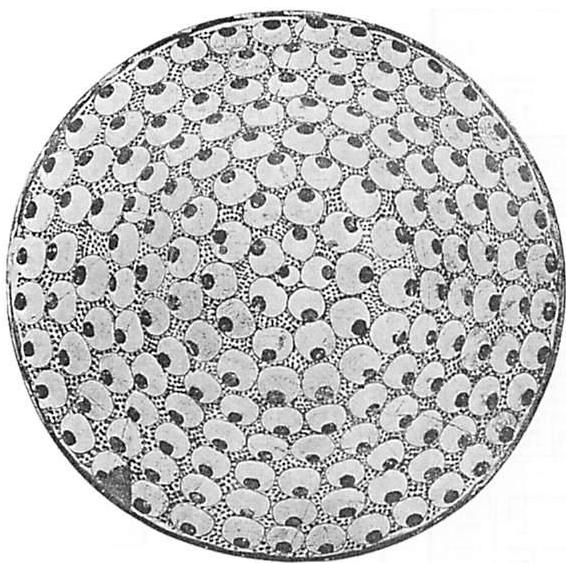

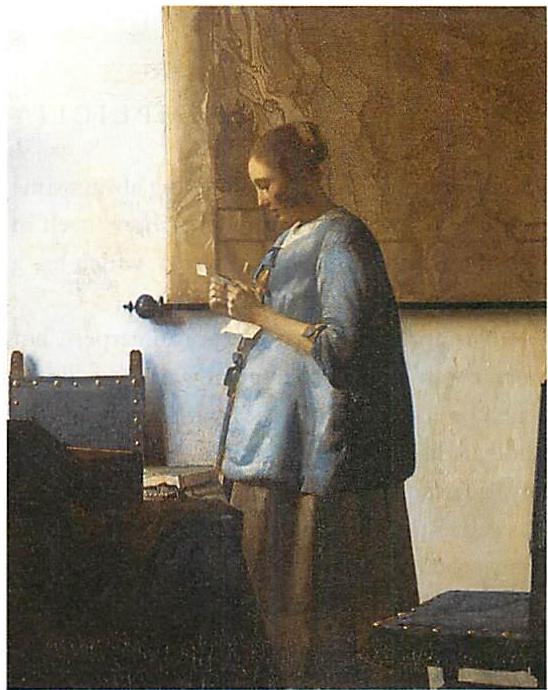

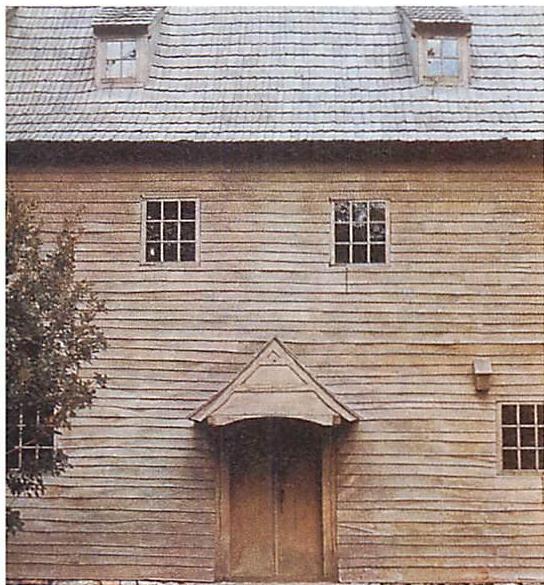

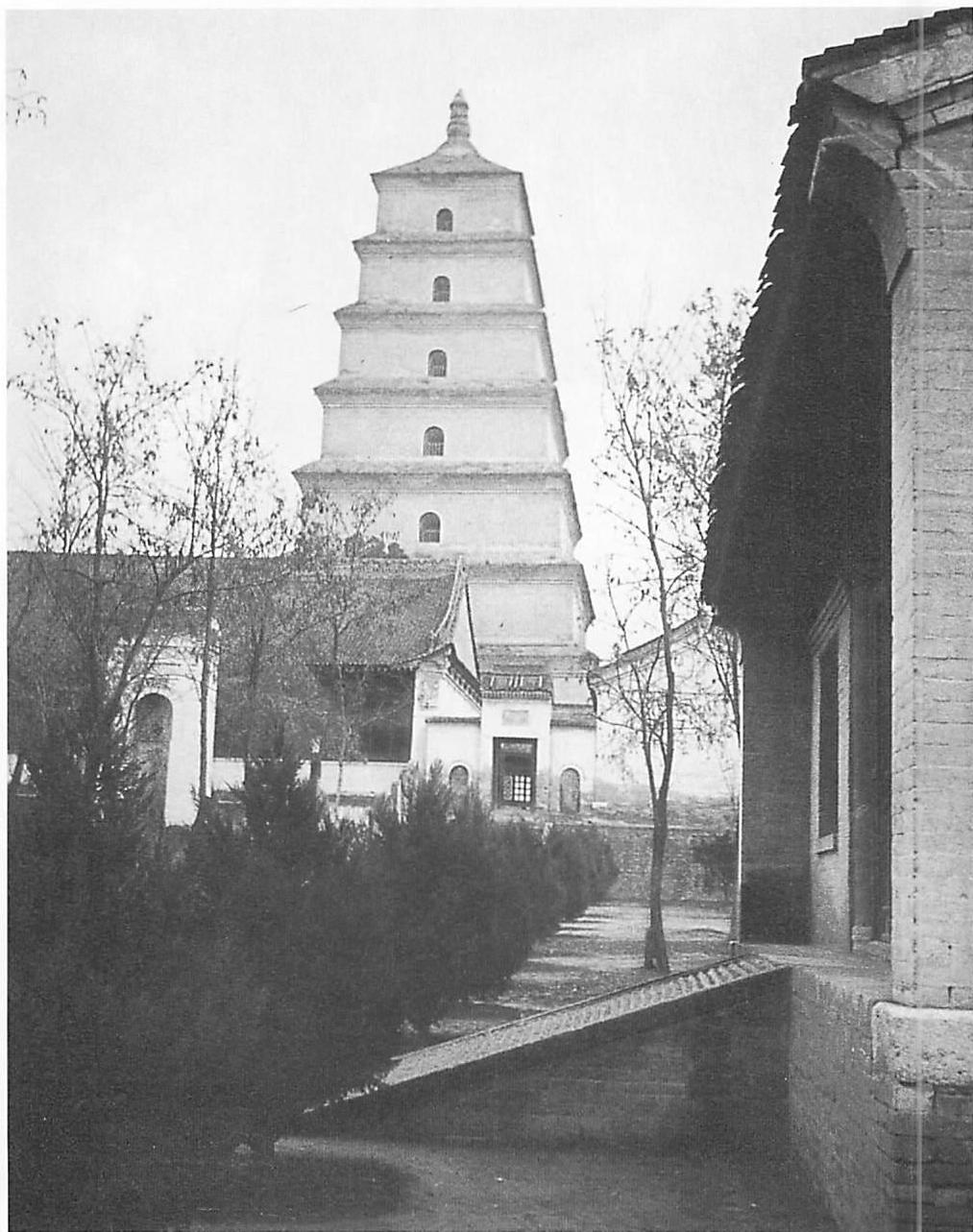

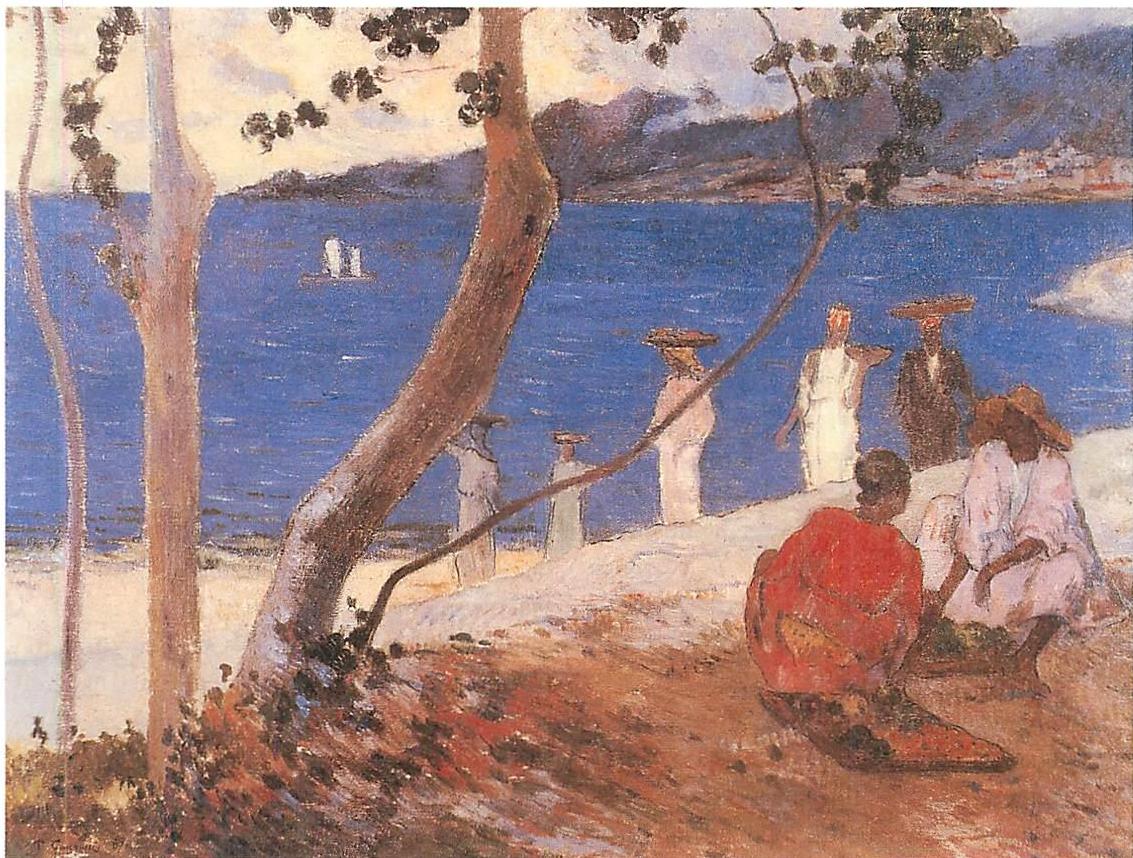

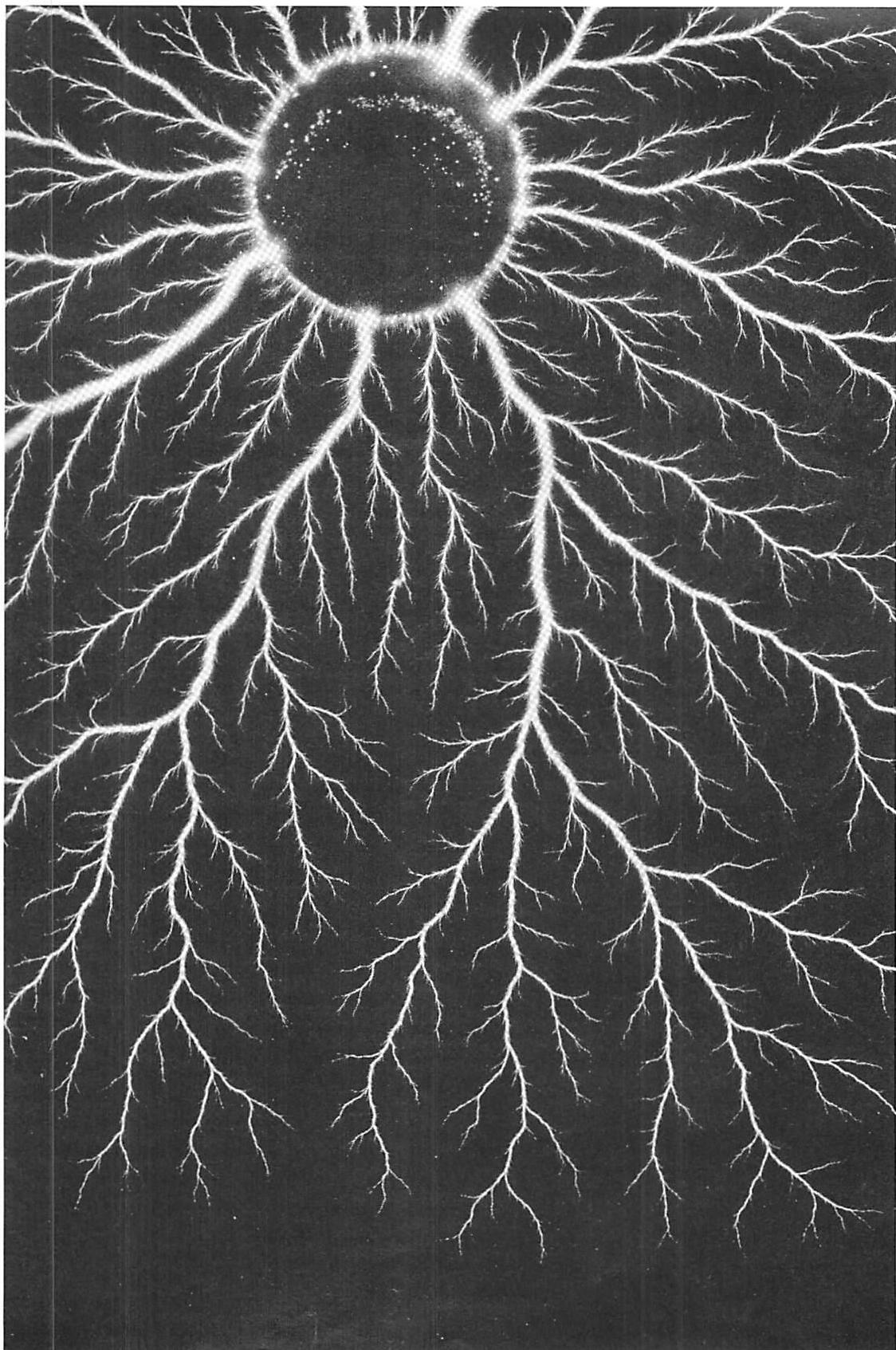

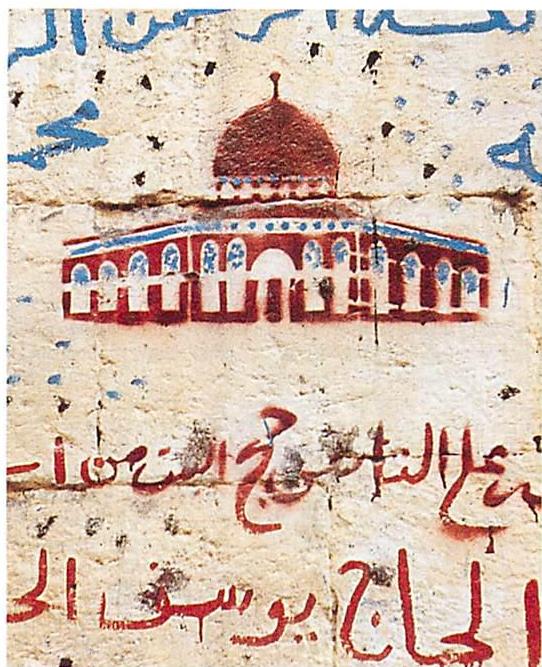

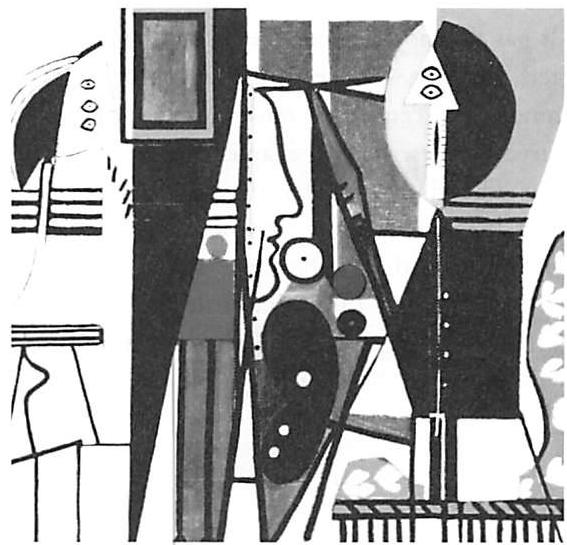

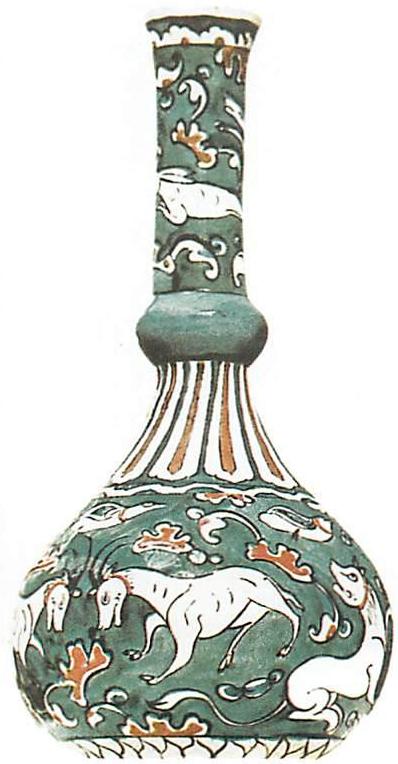

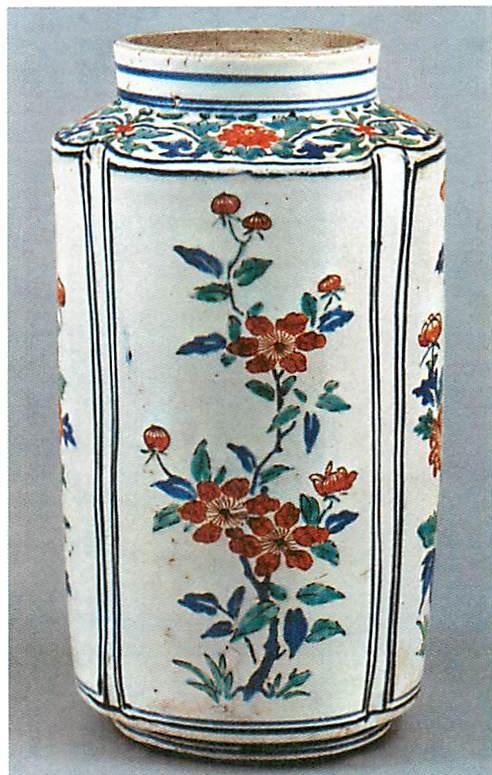

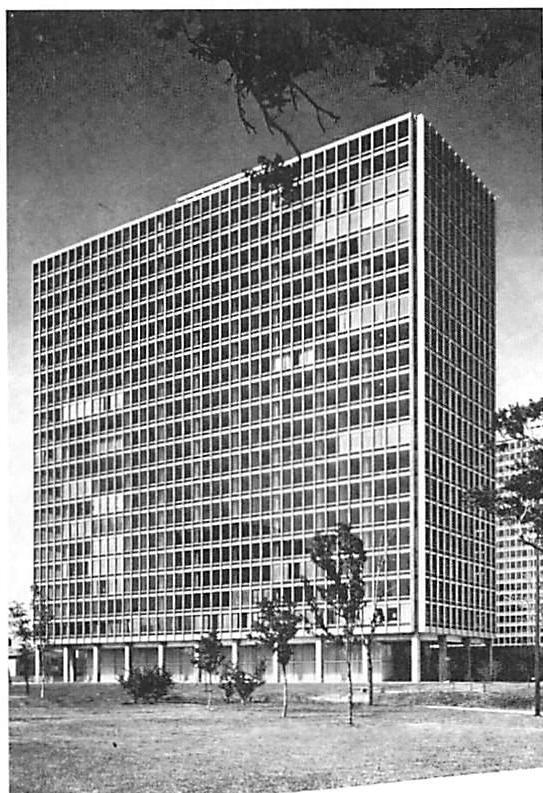

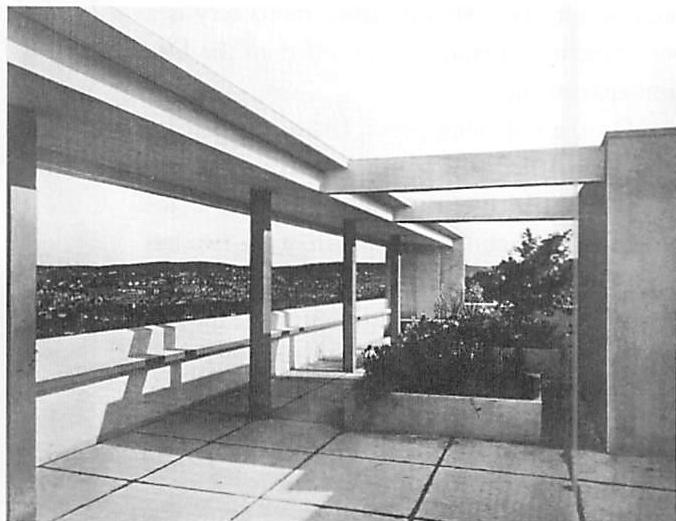

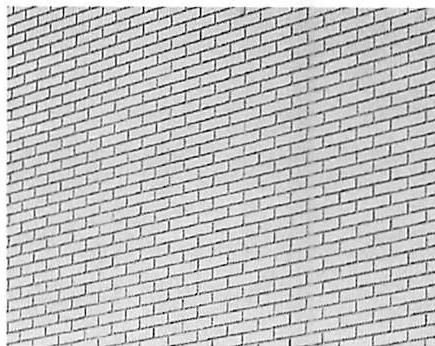

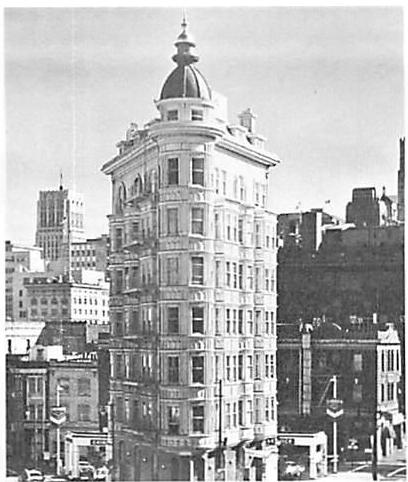

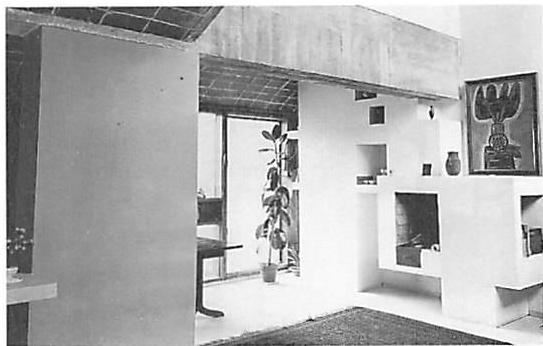

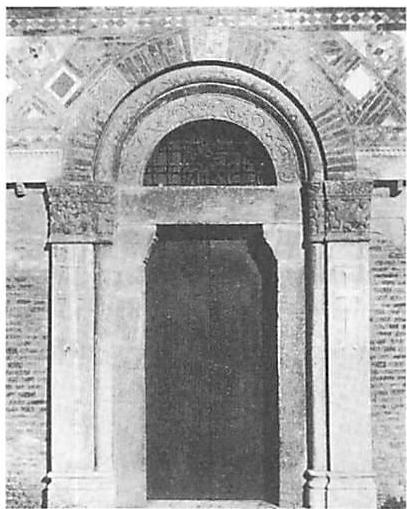

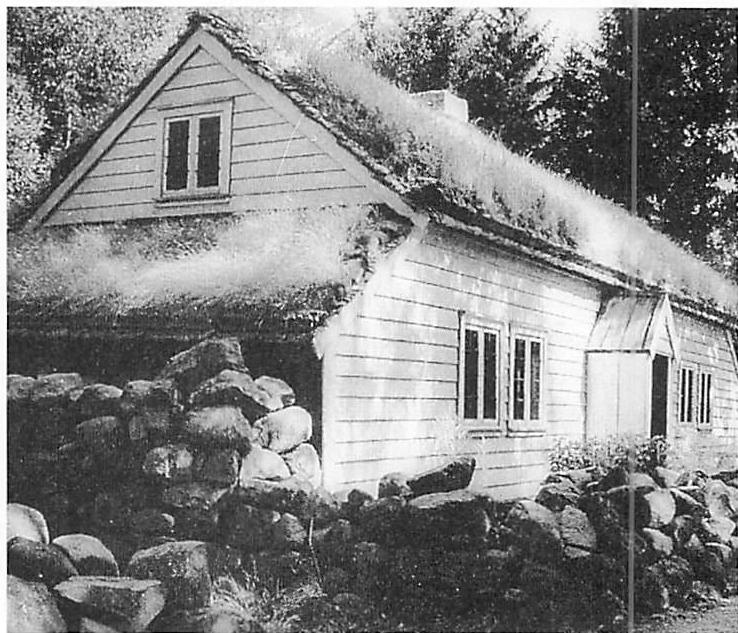

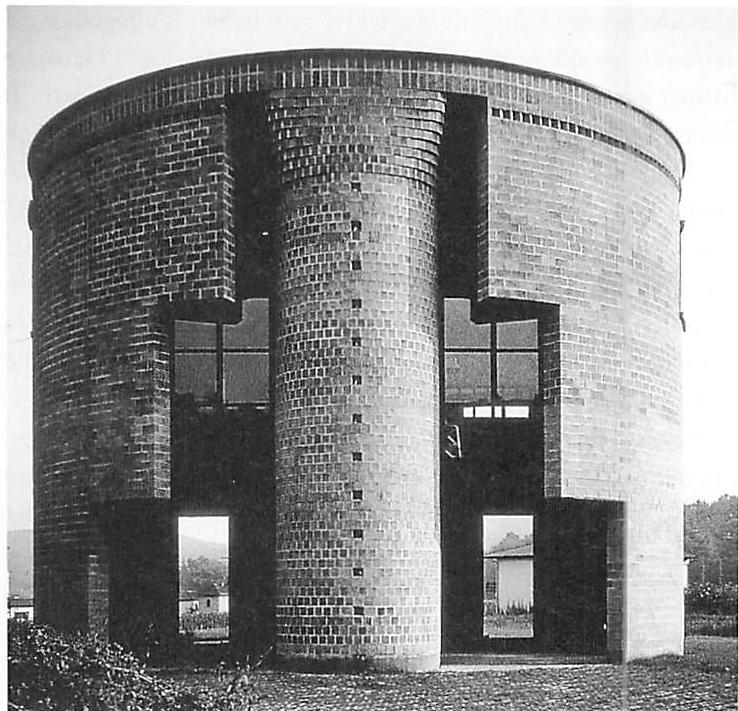

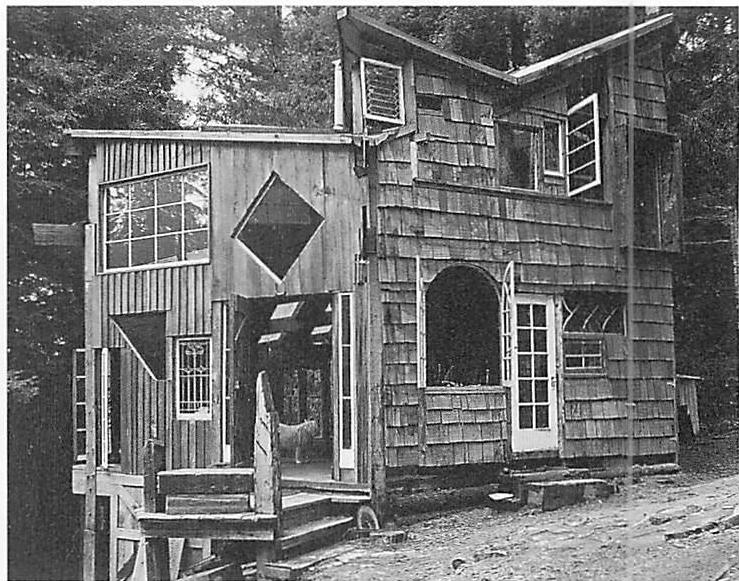

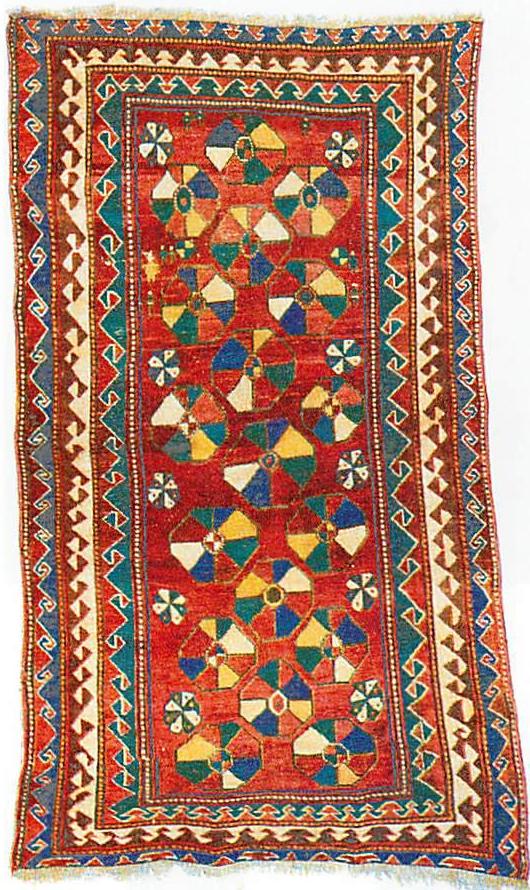

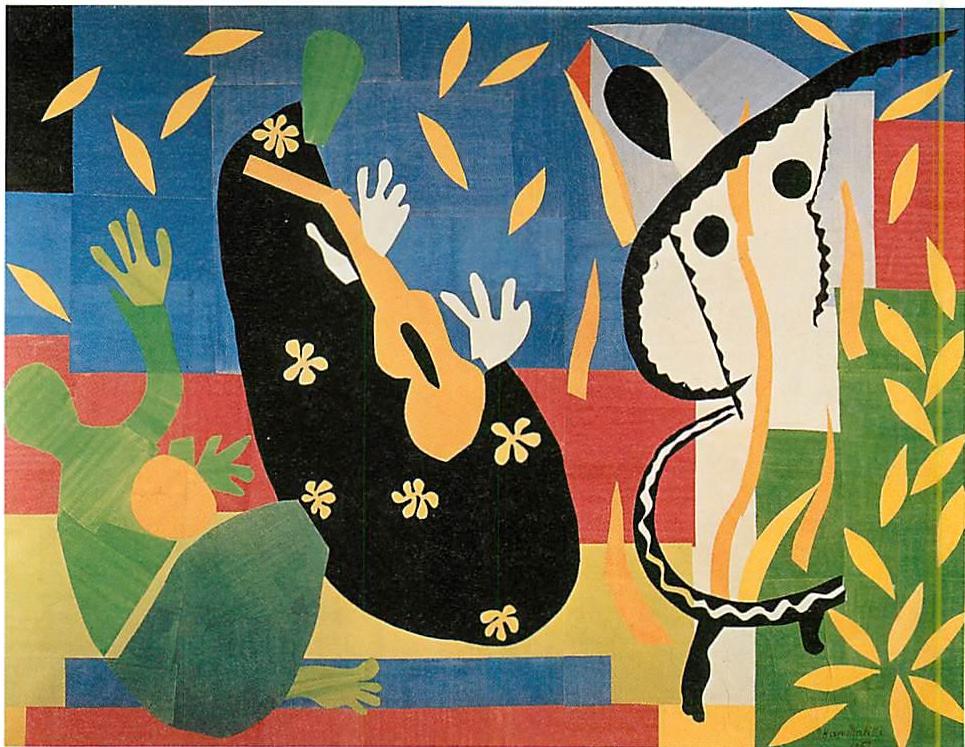

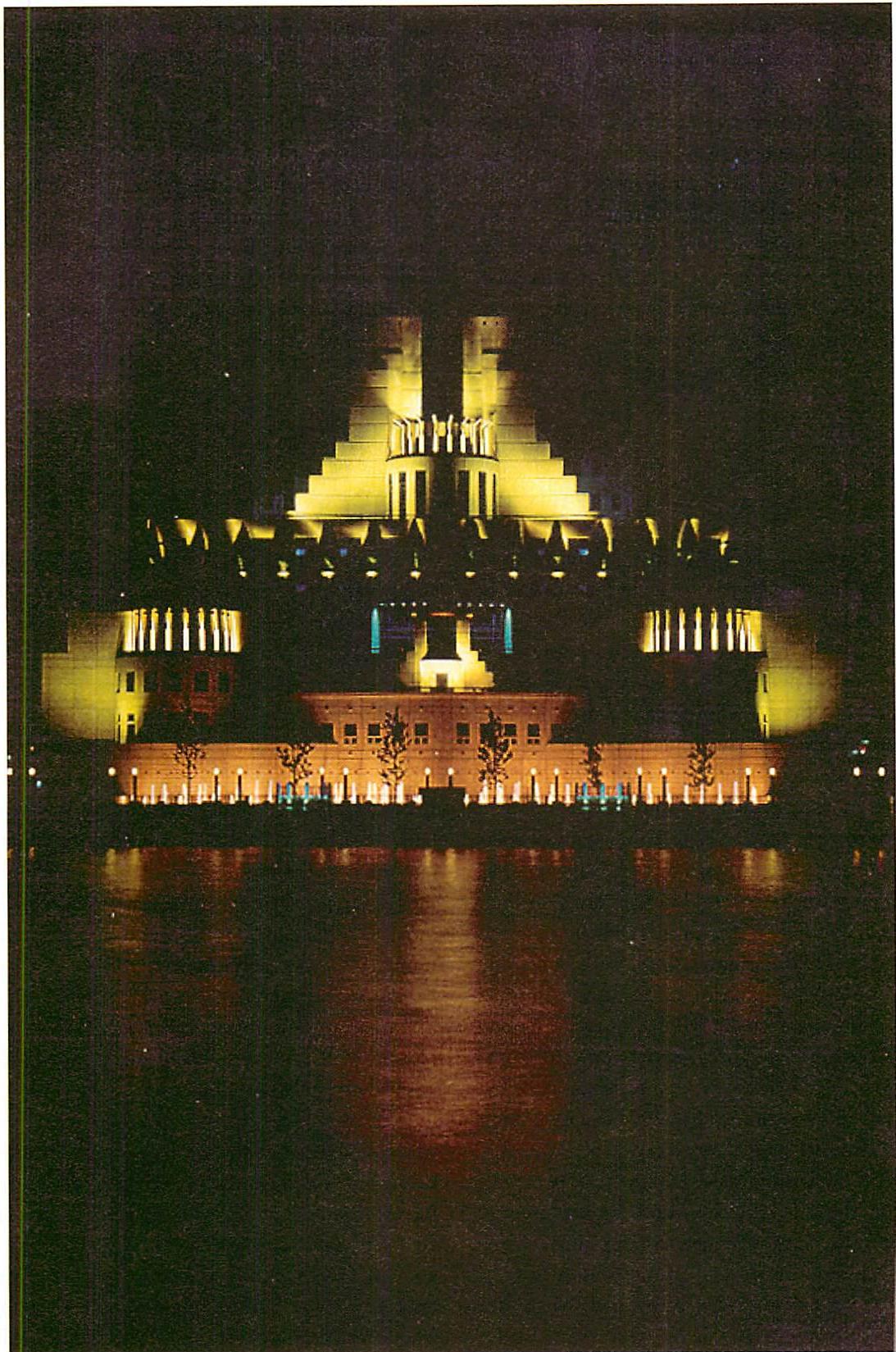

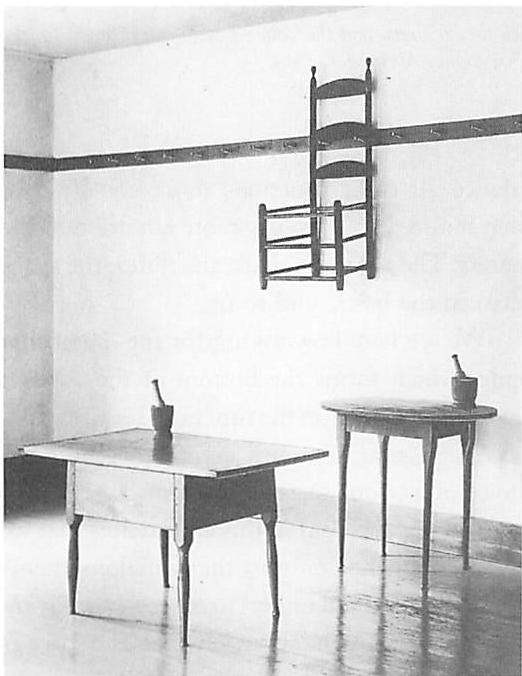

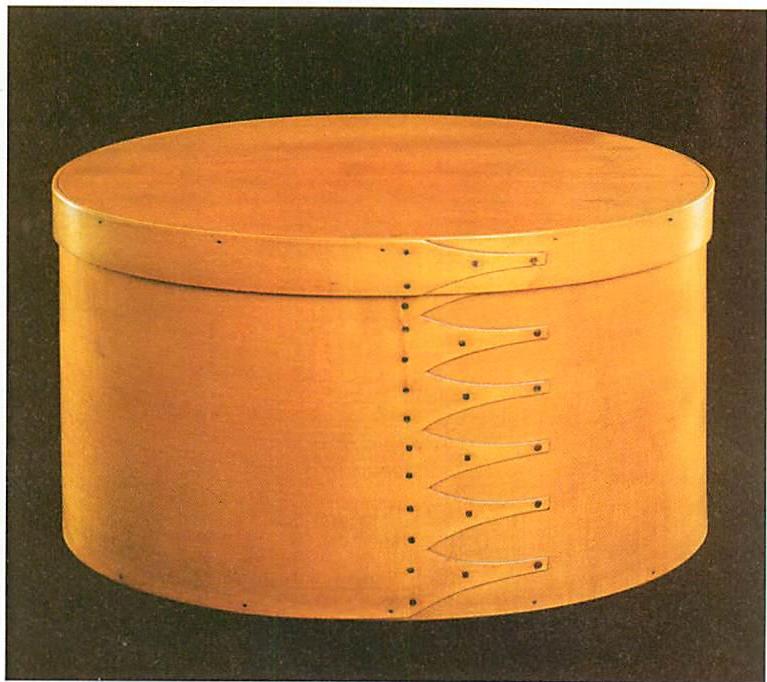

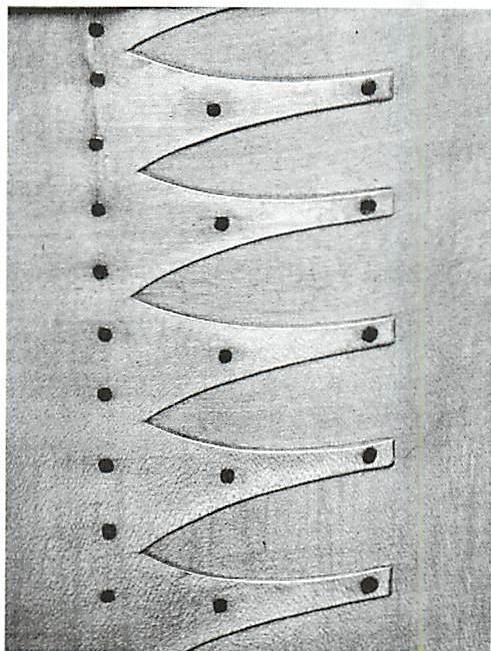

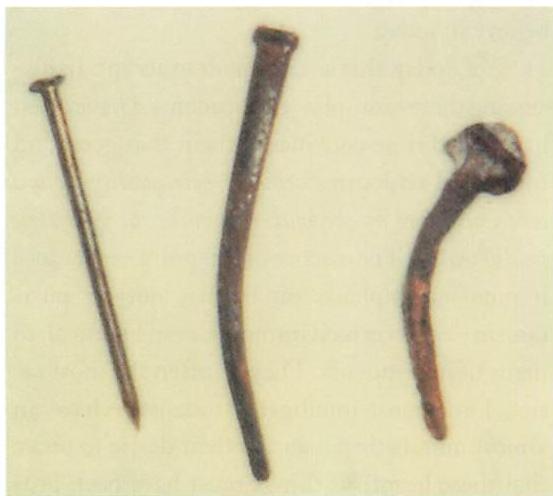

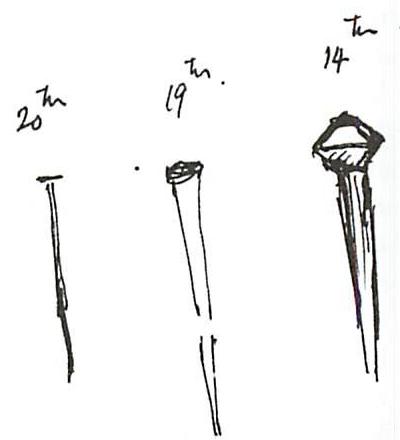

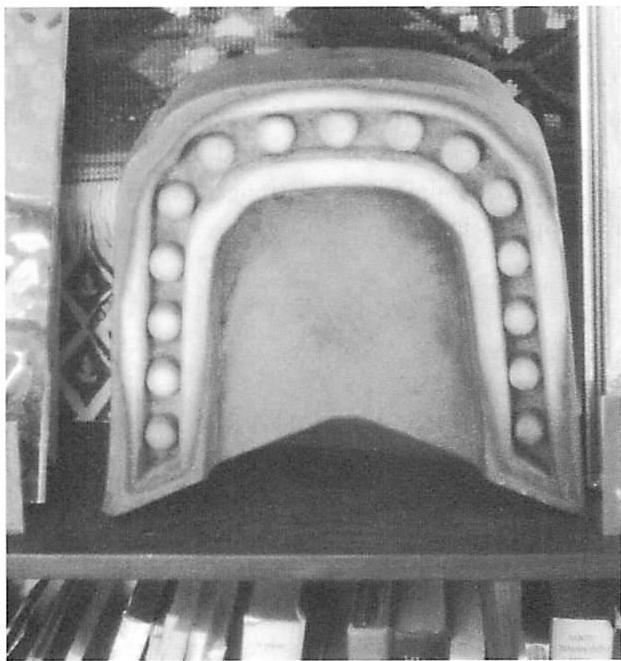

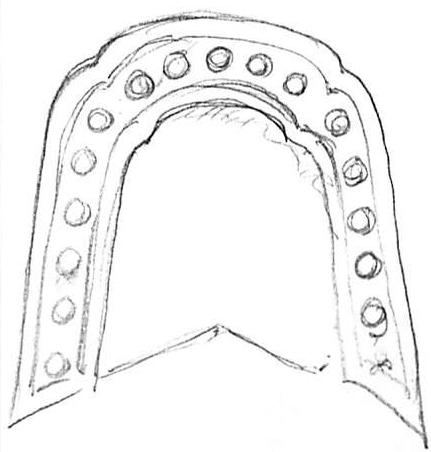

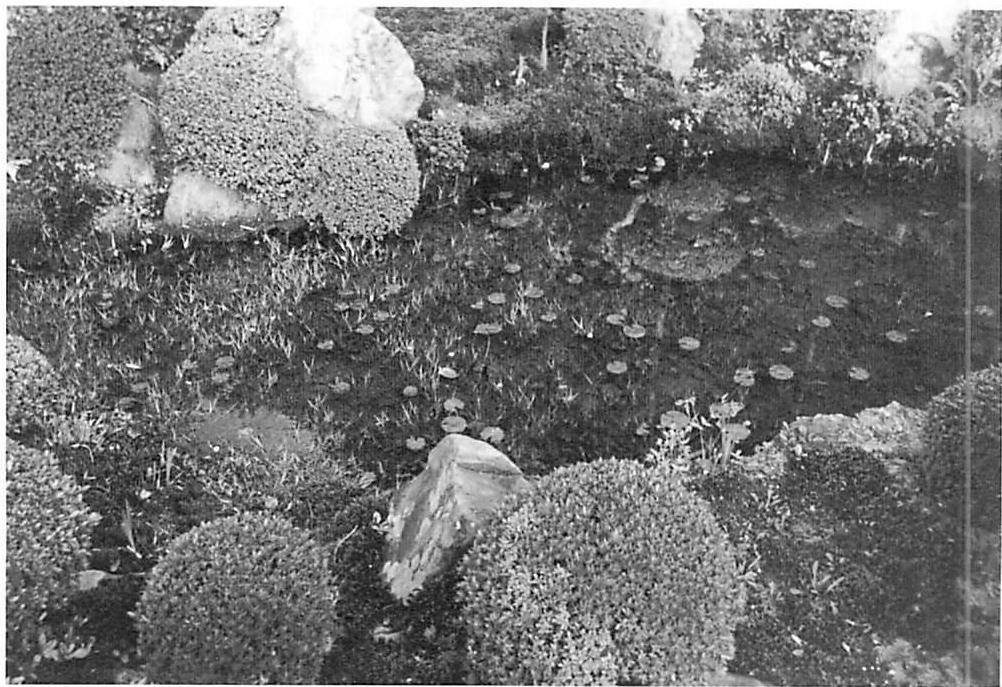

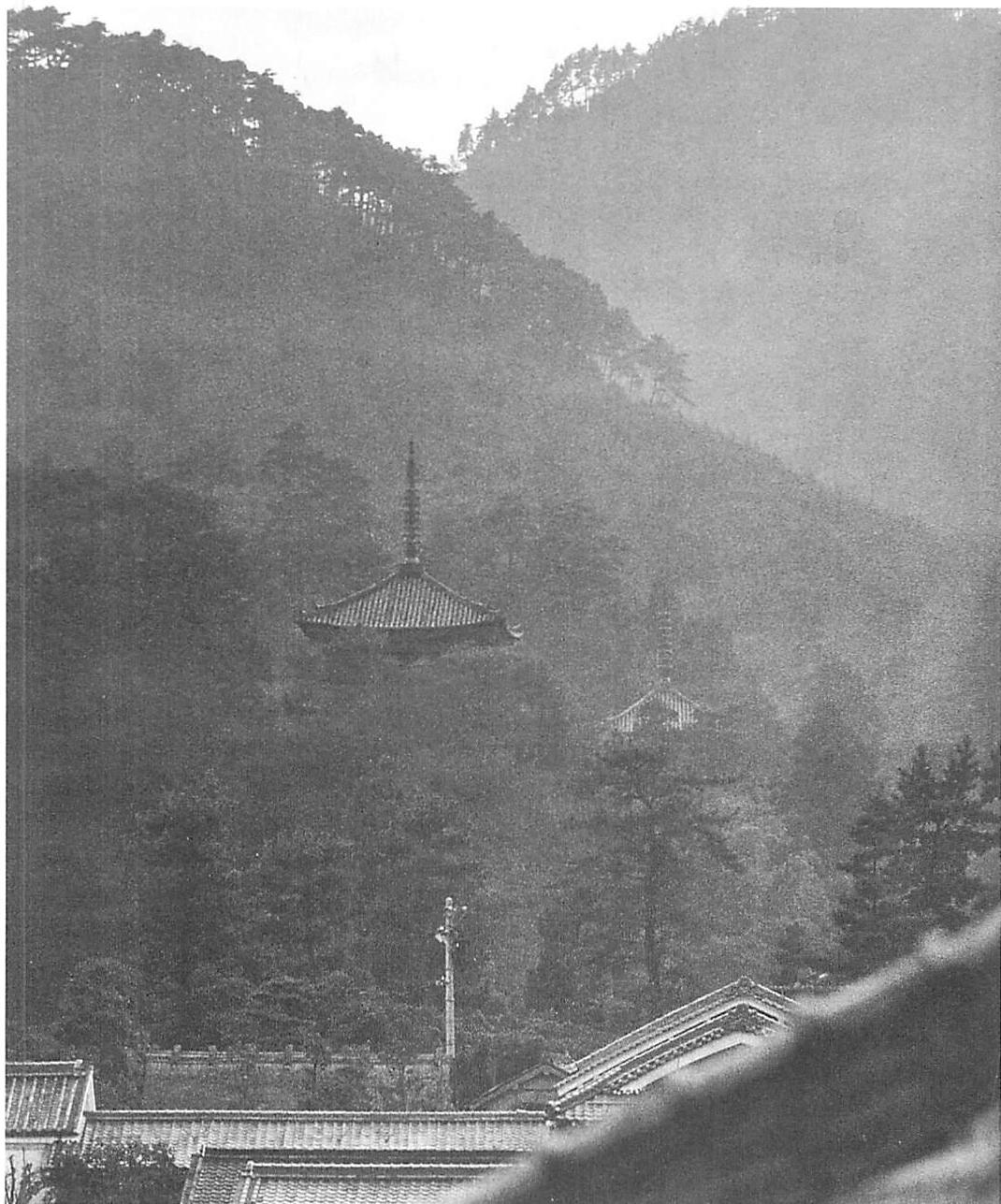

Look at the yellow tower on the facing page. It has the smile of the Buddha, of life and simplicity. It moves us in the heart. I want a conception of order subtle enough to explain the way the yellow tower makes us feel. The conceptions of order which physics currently defines, and most other current ideas of order, are simply inadequate for a profound task like this.

Scientists have been trying to define order for about a century. The idea of order as a precise concept first entered physics as a by-product of thermodynamics, when the orderliness of molecules in a perfect gas was analyzed numerically by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1872 through the idea of entropy. Unfortunately the order which can be treated as negative entropy is too simple, and, for complex artistic cases, almost trivial.¹ In the 20th century, the hunger of the scientific community for some precise concept of order was so great that attempts to extend the notion of thermodynamic order to cover all order were made by many writers outside the field of physics.² Sober generalizations of the thermodynamic concept of order were also made by physicists.³ None of this went far enough to be helpful to artists.⁴

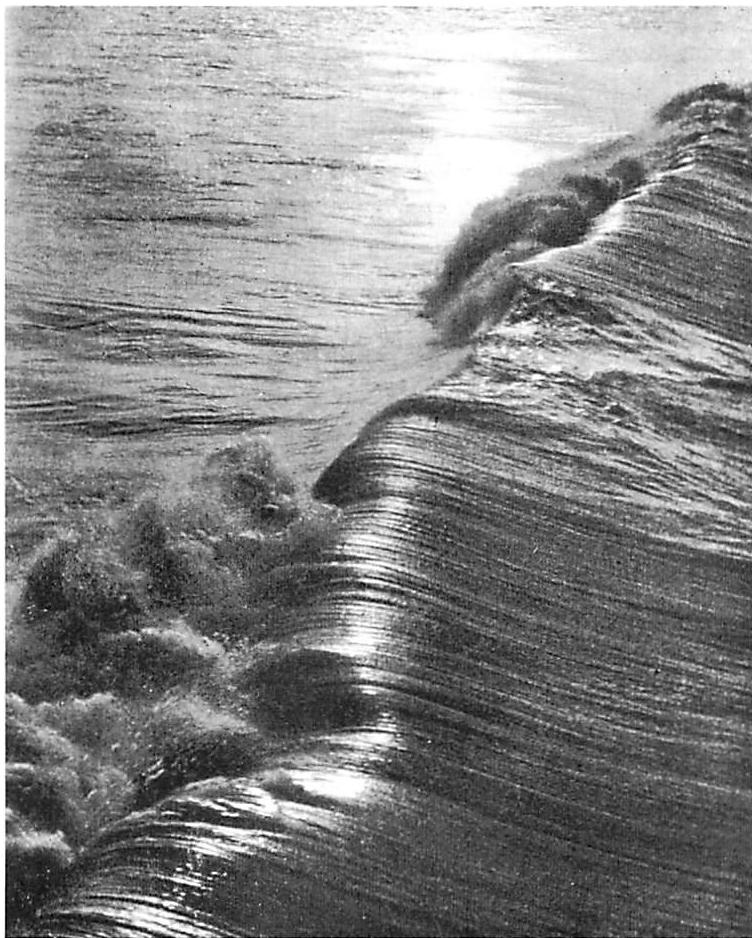

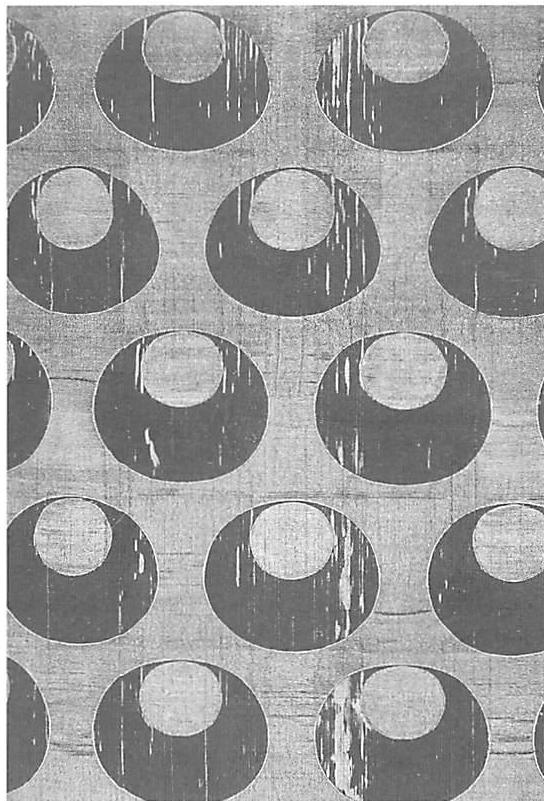

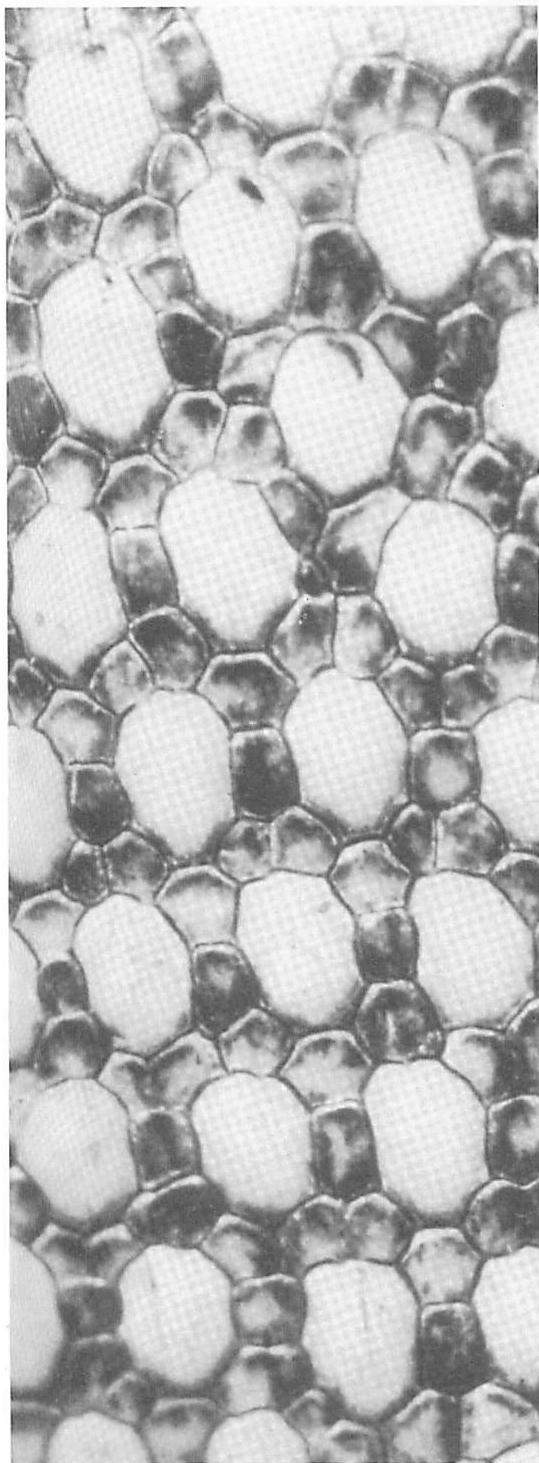

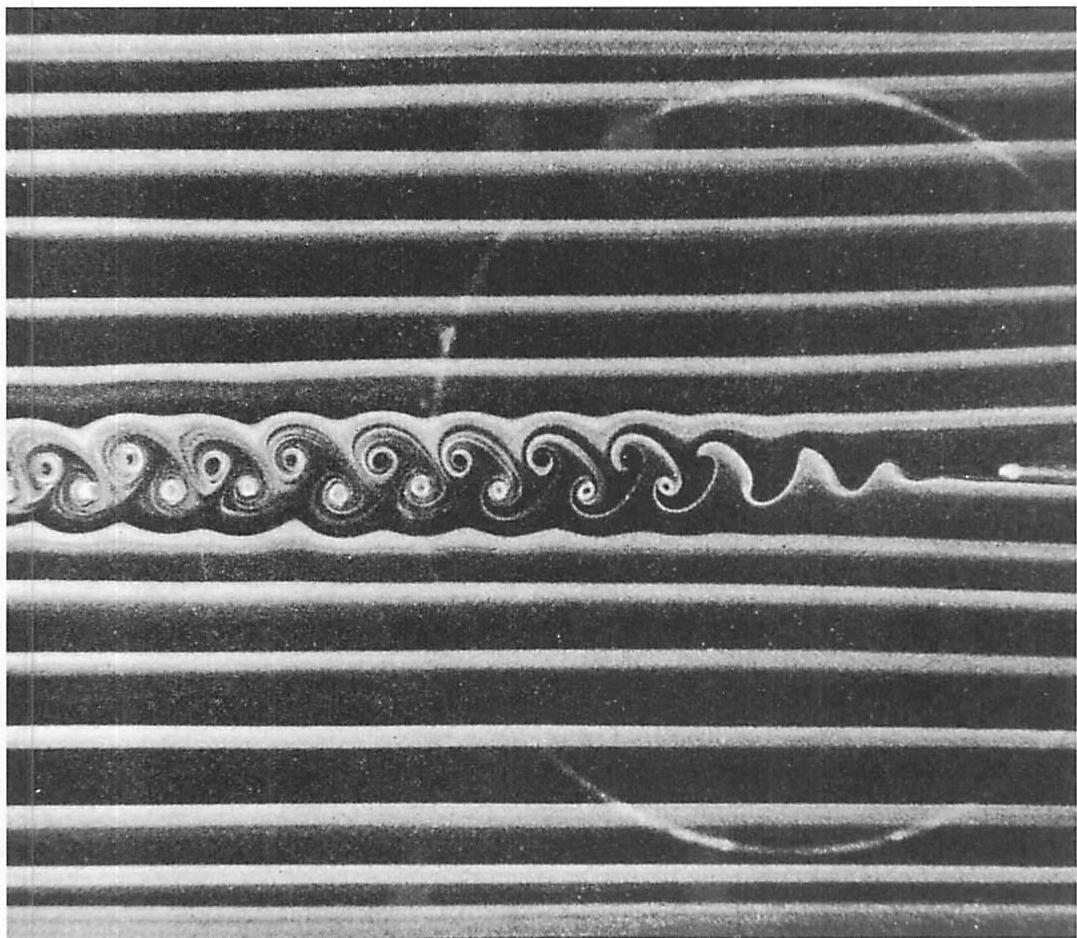

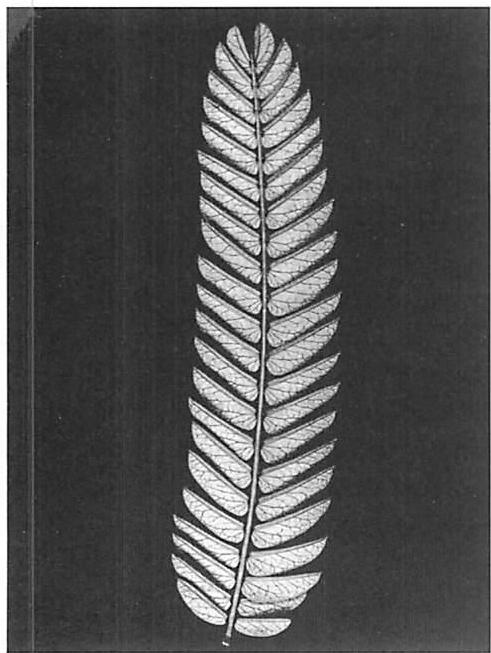

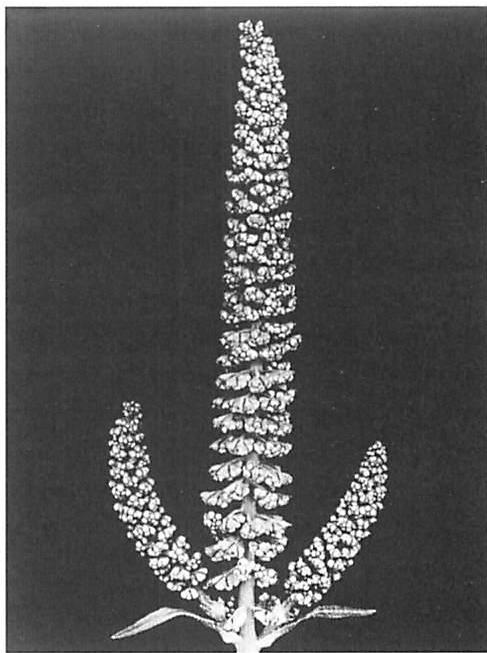

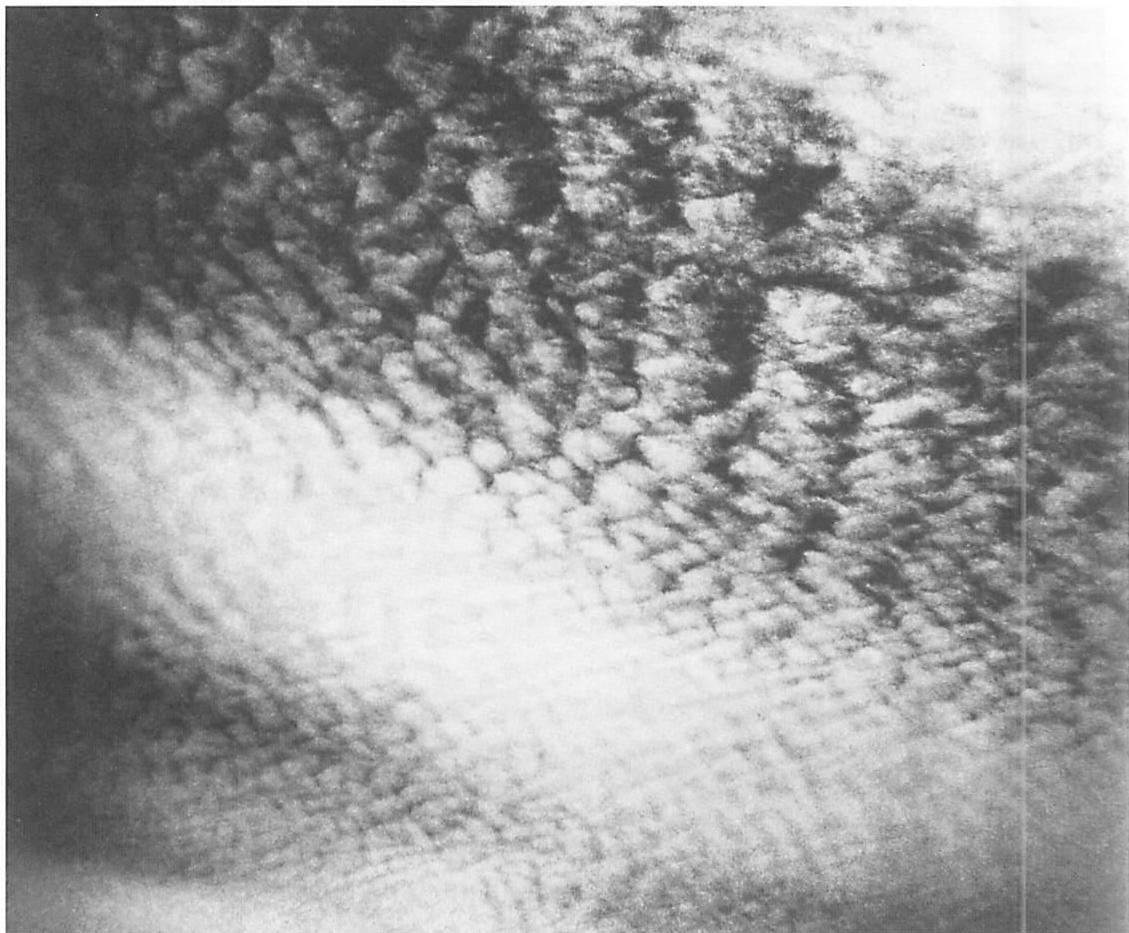

What other ideas of order can we get from modern physics? We could concentrate on special types of order like crystallographic order, defined by repetition.⁵ But this concept is too limited to be much help in making something subtle and beautiful. We could develop conceptions of military or hierarchic order. These too have been analyzed, but are too limited to be much help.⁶ Complex patterns generated by interacting rules are more interesting, and raise the possibility of seeing all order as the product of a computable generative process.⁷ This could give us a general view of order as any system produced by interacting generative morphological rules.⁸ In other cases of this type we have an orderly pattern-making process based on the interaction of rules which can simulate the motion of a thrown ball, or a breaking wave. Still more complex, we are beginning to have some idea of biological order, an order of a growing thing in which one system unfolds continuously to form another.⁹ In recent years, biologists have tried to formulate more sophisticated concepts of order.¹⁰ Unfortunately, these attempts have also not yielded results which are practically useful in the art of building.

Deeper theories of order have been attempted. A preliminary sketch of a very much deeper theory was once made by the physicist Lancelot Whyte, who tried to develop a view of all biology as a science of asymmetrical ordered structures.¹¹ The theory of catastrophes, which tries to describe the birth of configurations out of chaos, has been developing in recent years and is considered by many to be promising.¹² Perhaps one of the clearest statements so far has been expressed by the physicist David Bohm. Bohm tried to outline a possible theory in which order types of many levels exist and are built out of hierarchies of progressively more complex order types.¹³

But none of this, suggestive as it all is, is directly useful to a builder. Even the most advanced of these ideas is still not deep enough or concrete enough to give us practical help with architecture, where we actually try to create order every day. If I want to build a building as beautiful as the yellow tower, these theories of order

are not even remotely deep enough to help me in a practical fashion. None of these theories are even capable of helping us to understand the order of the yellow tower.

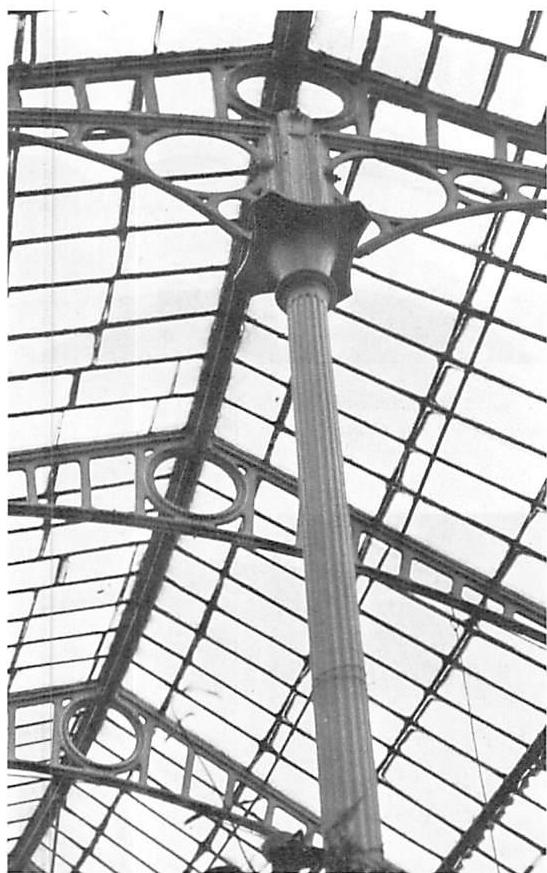

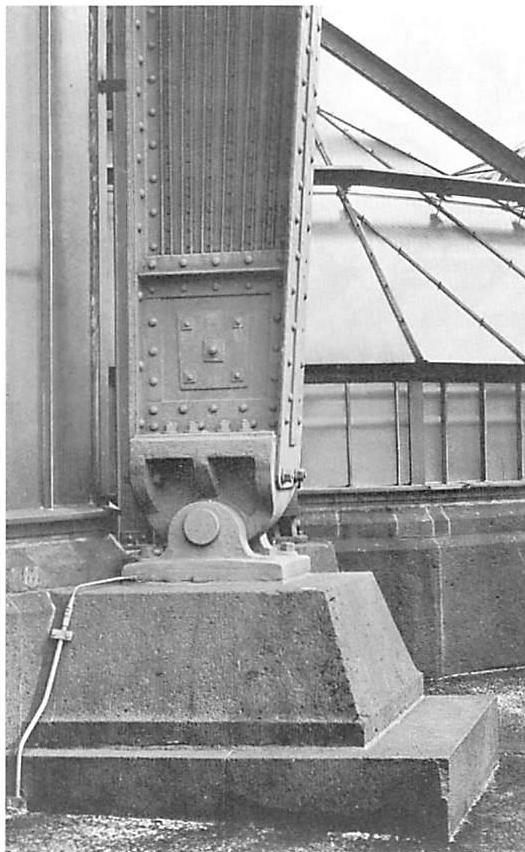

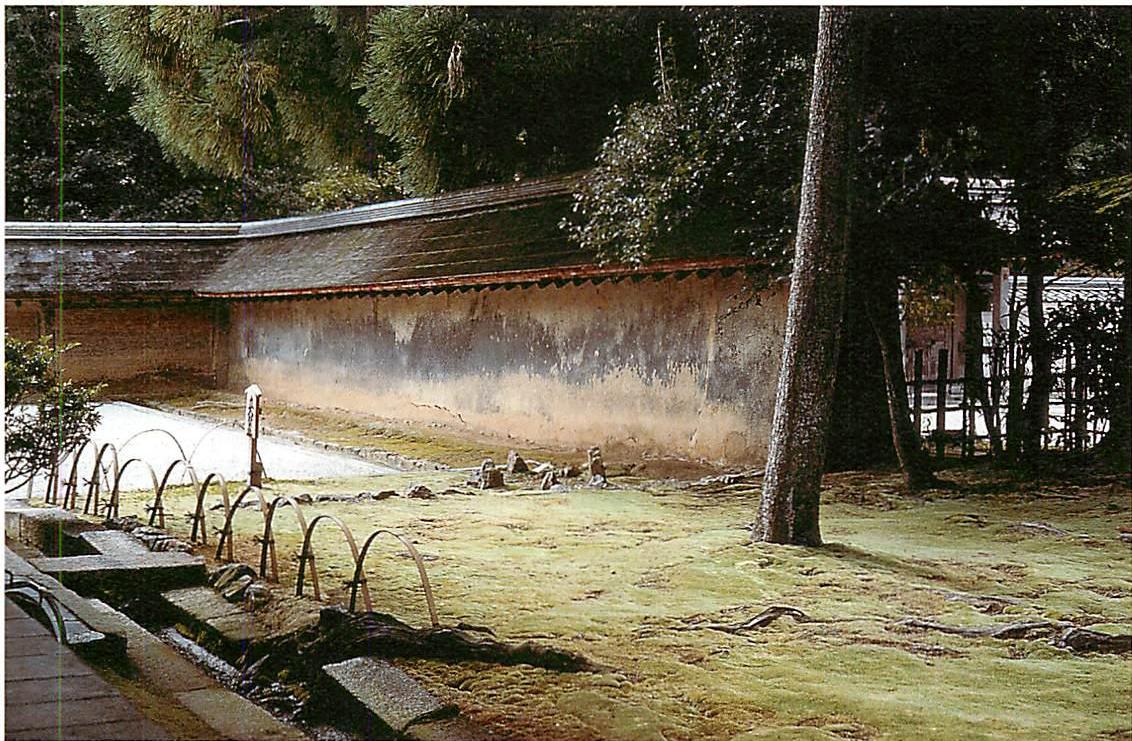

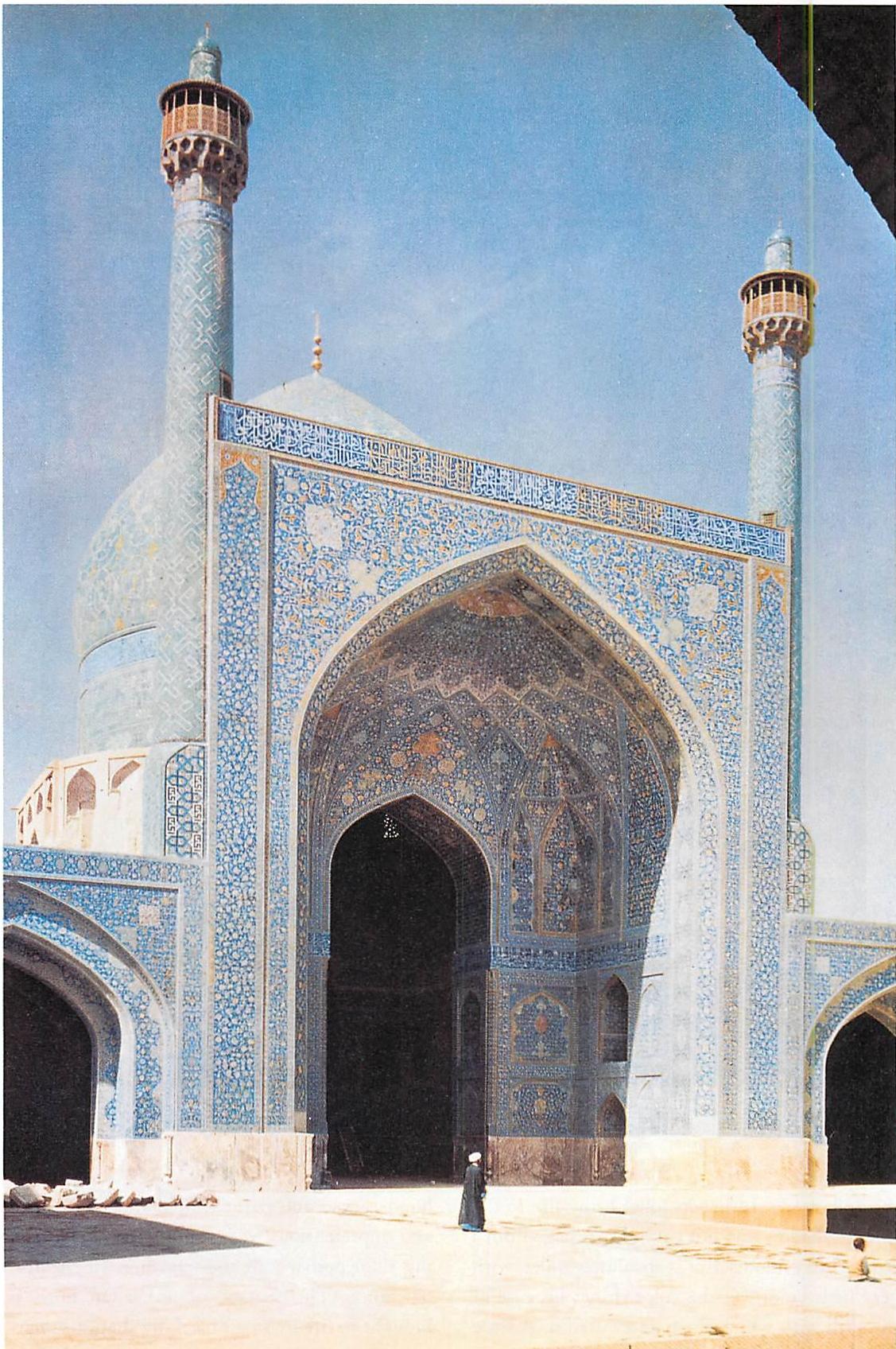

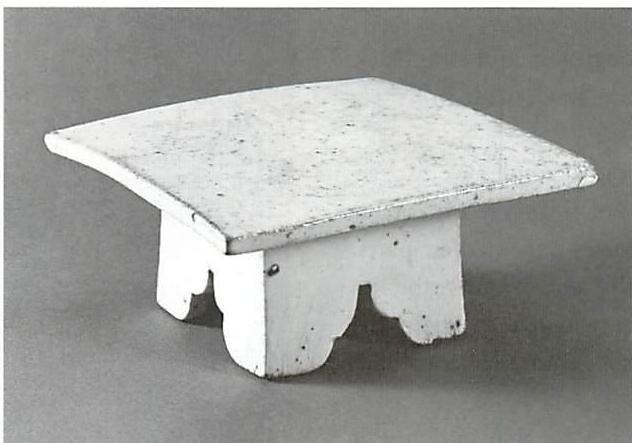

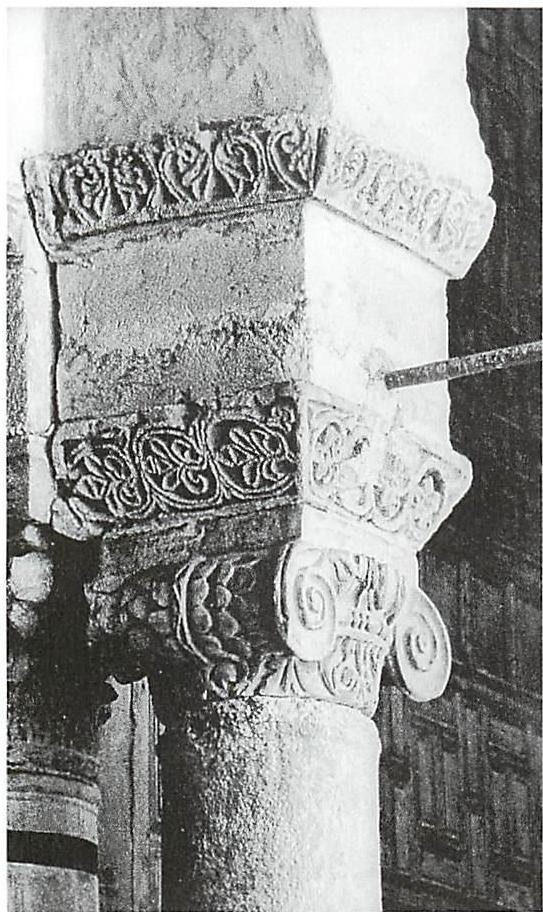

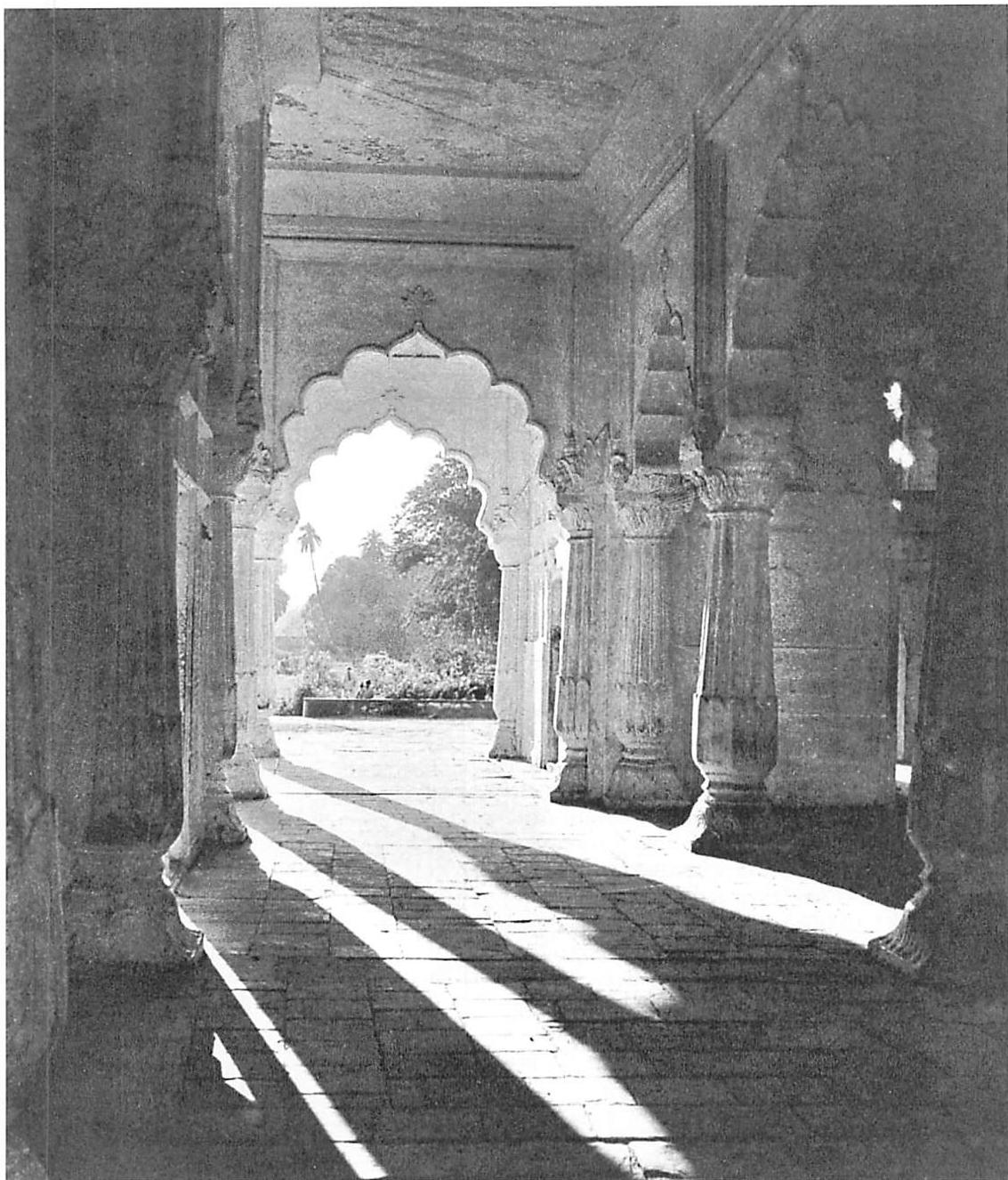

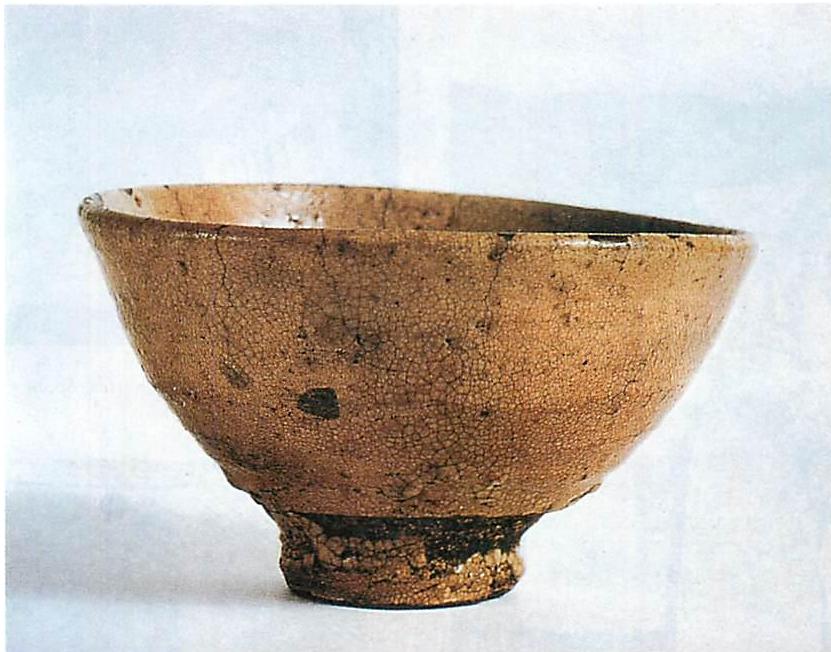

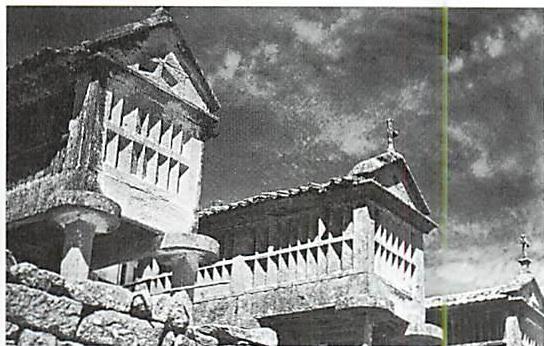

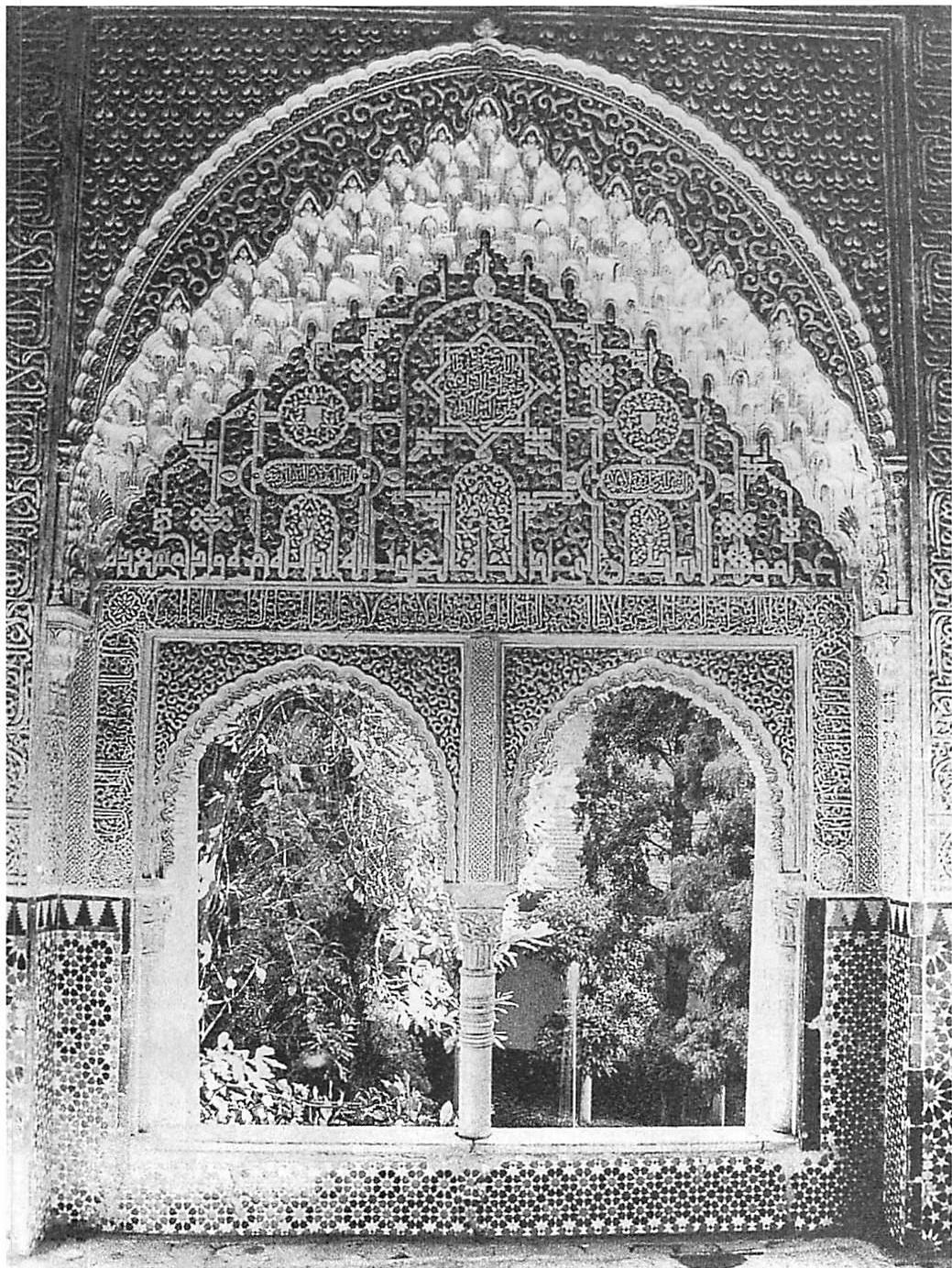

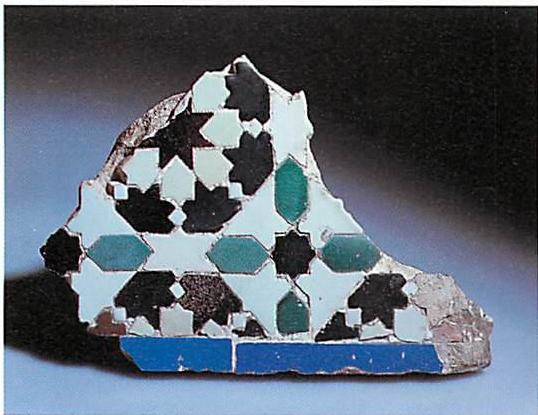

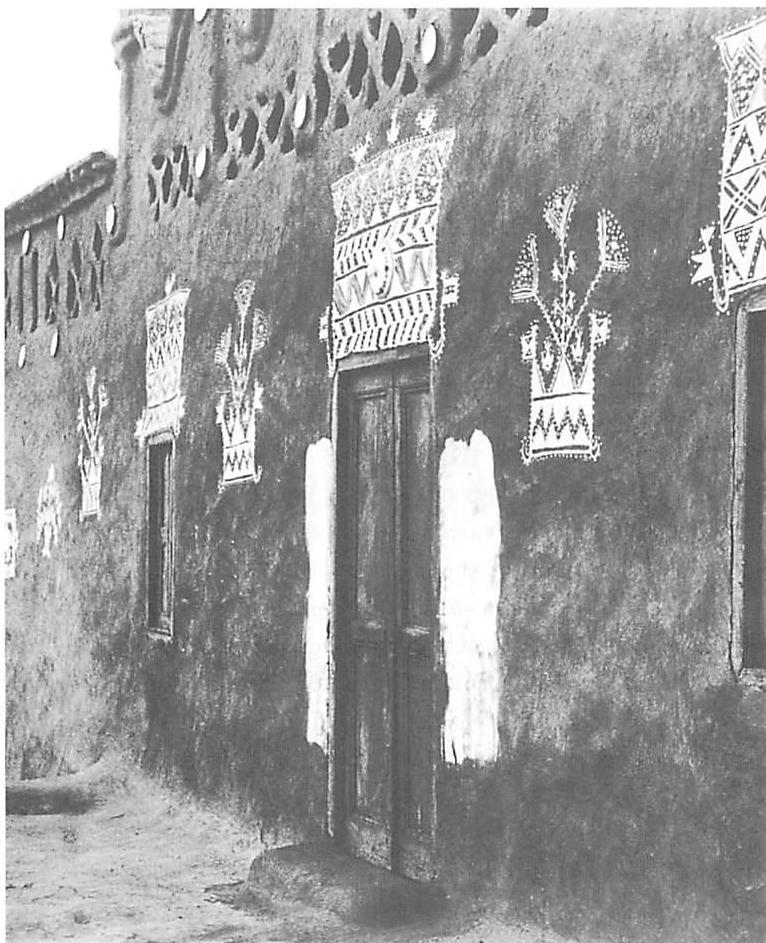

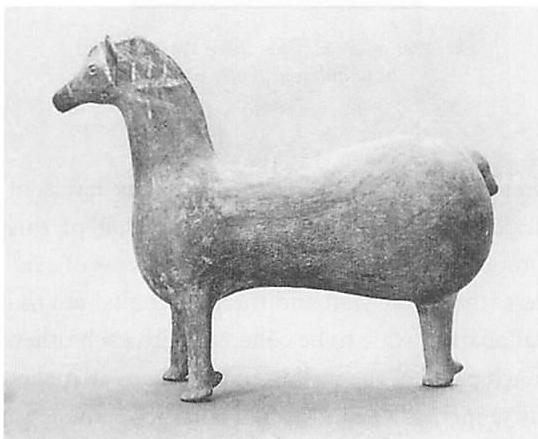

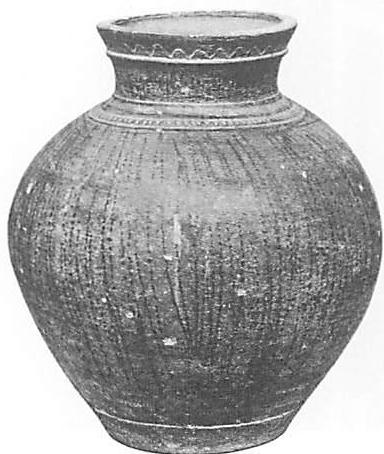

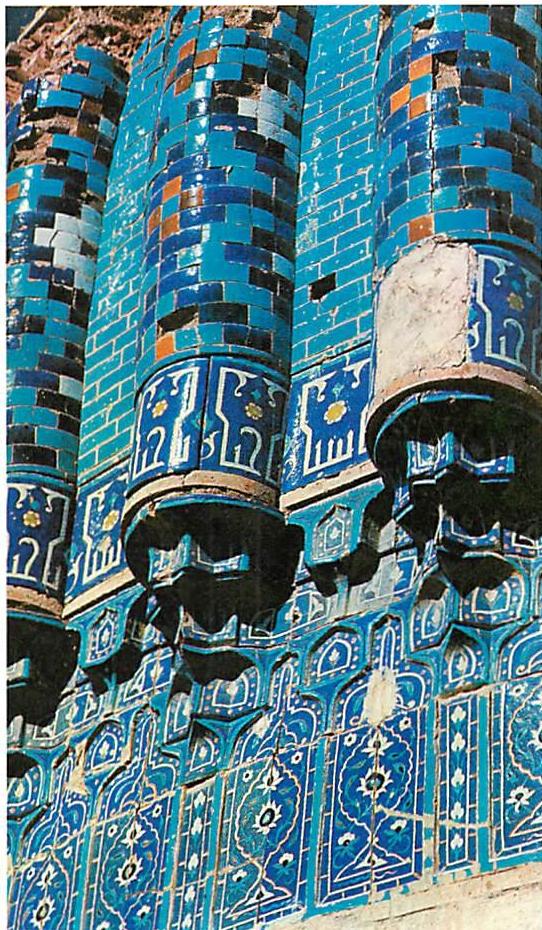

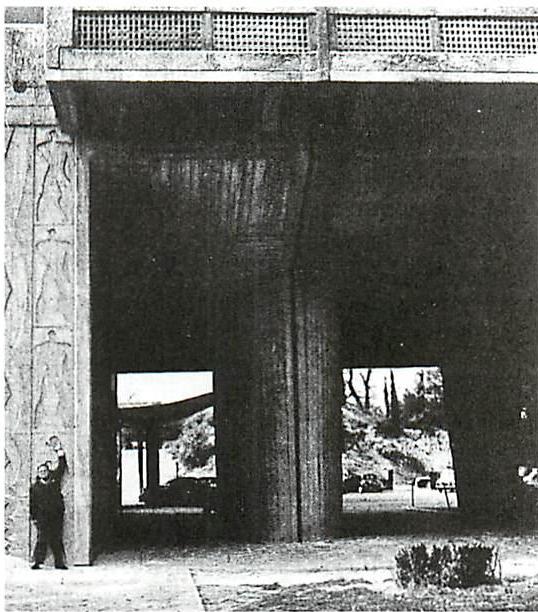

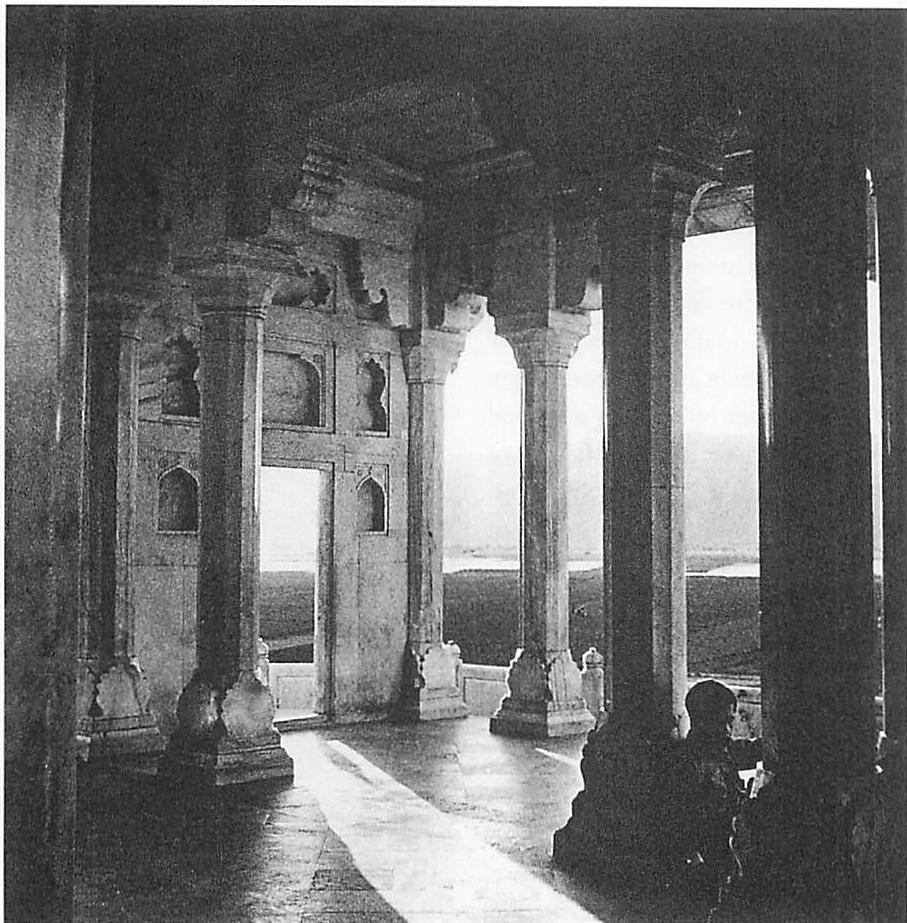

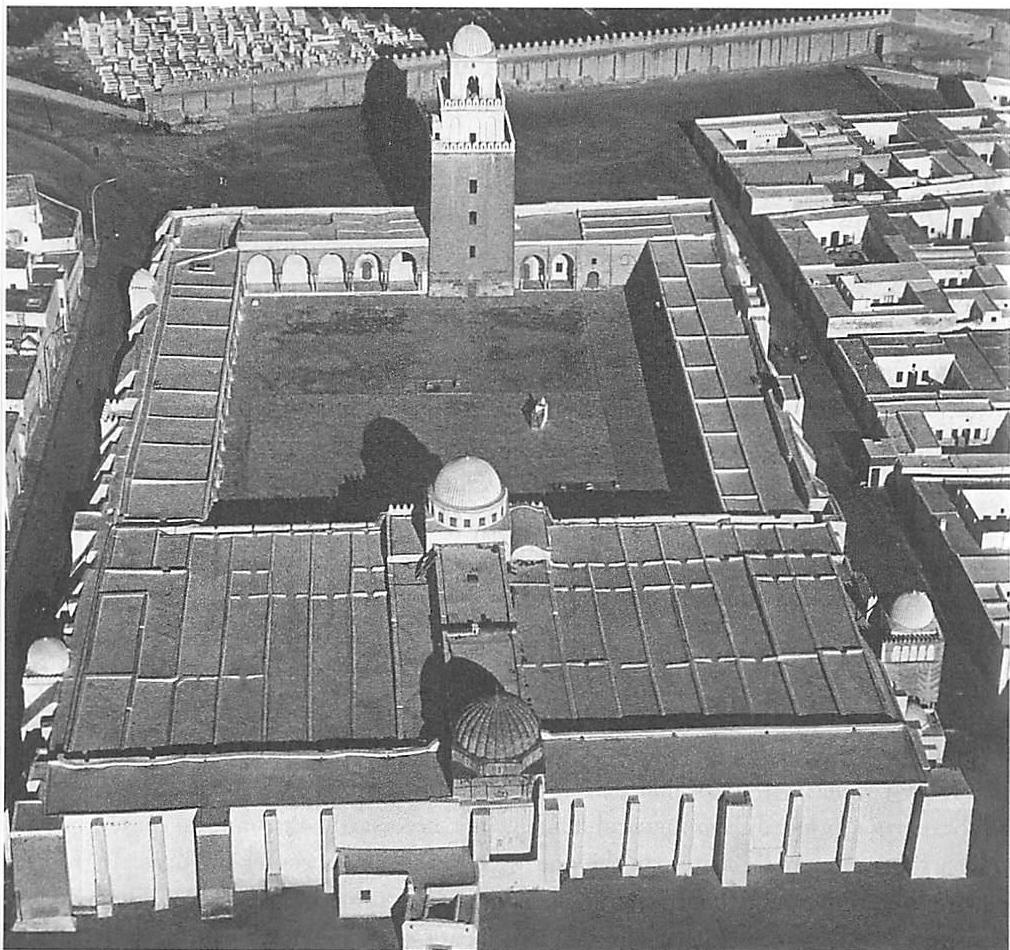

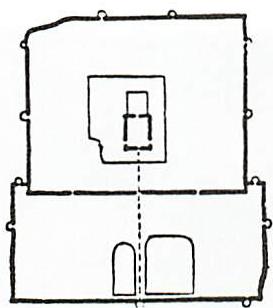

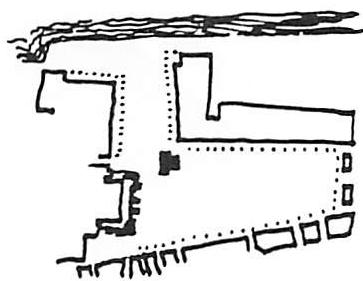

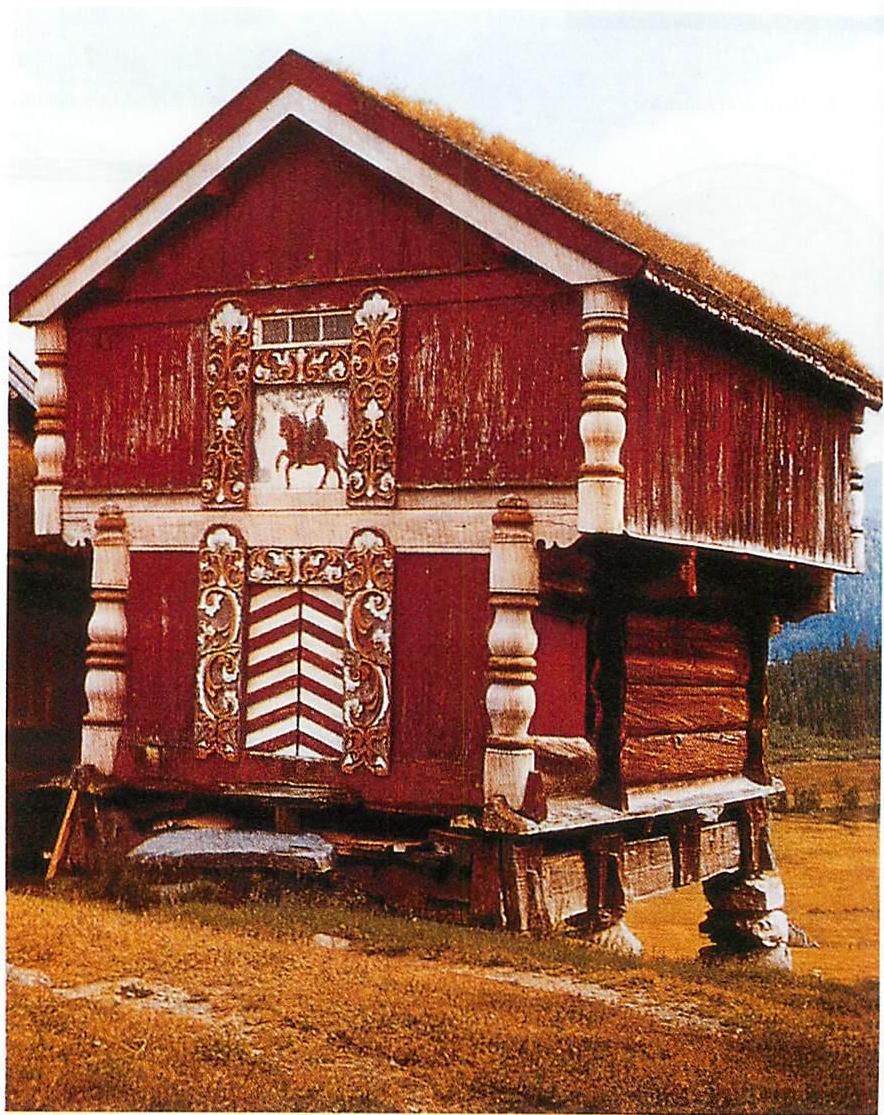

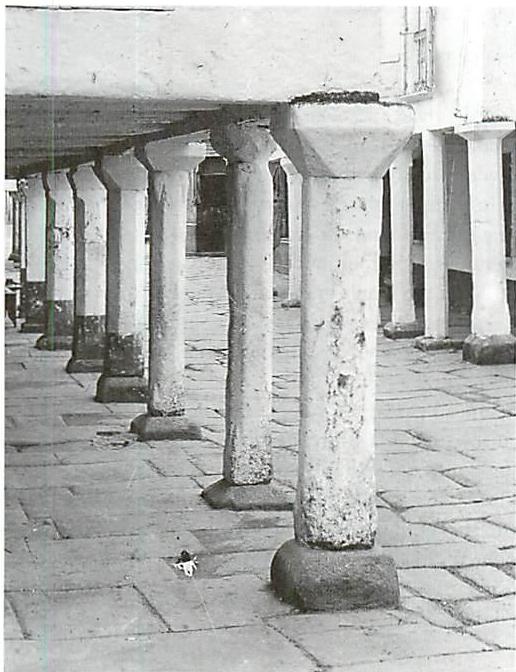

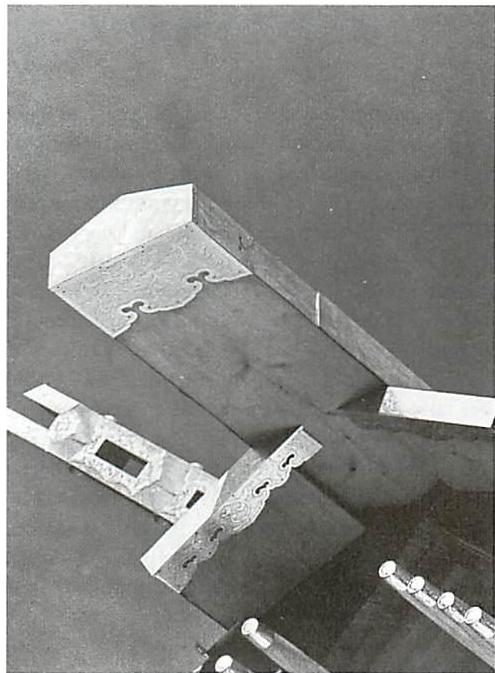

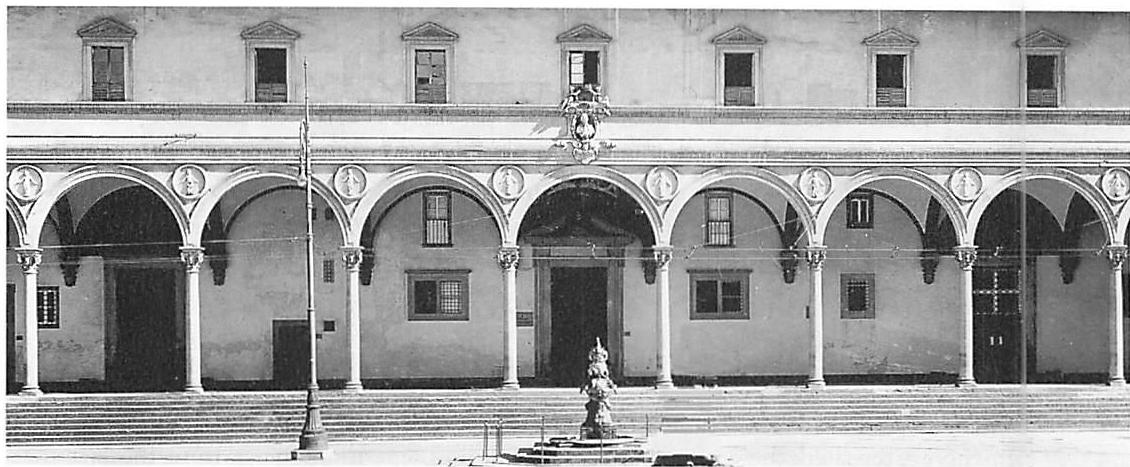

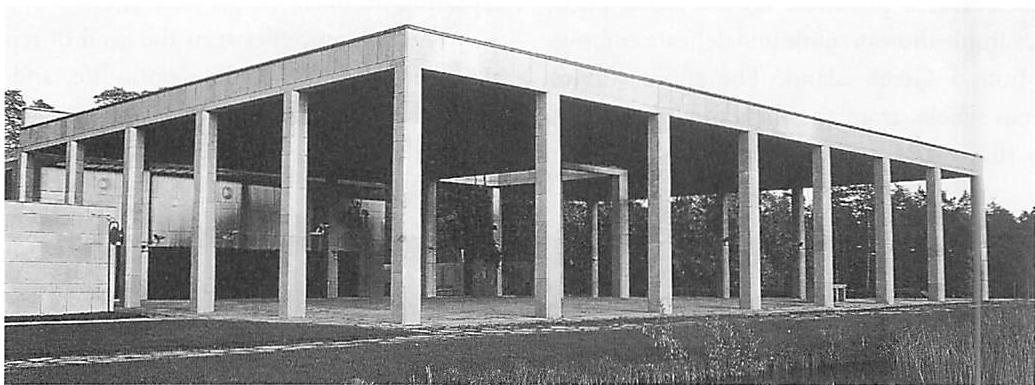

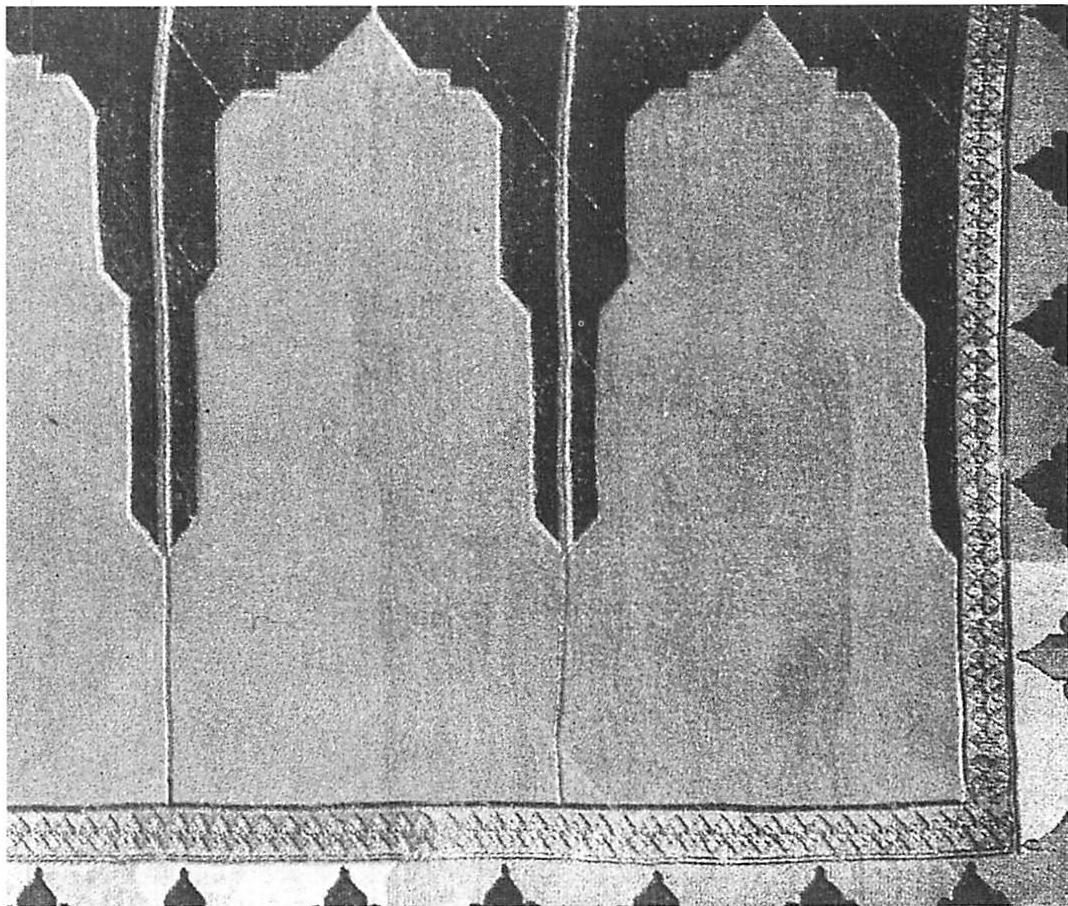

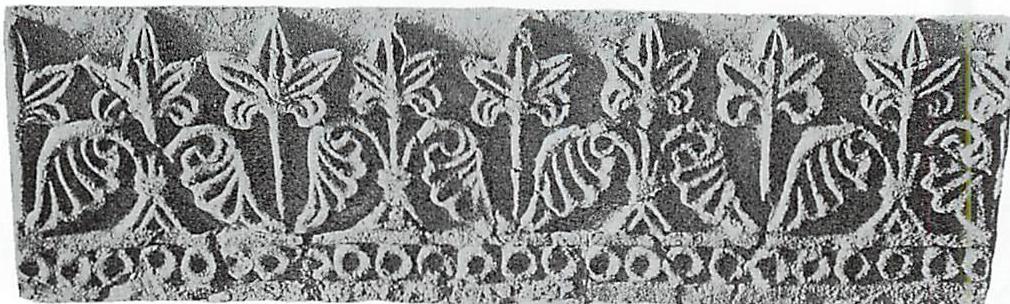

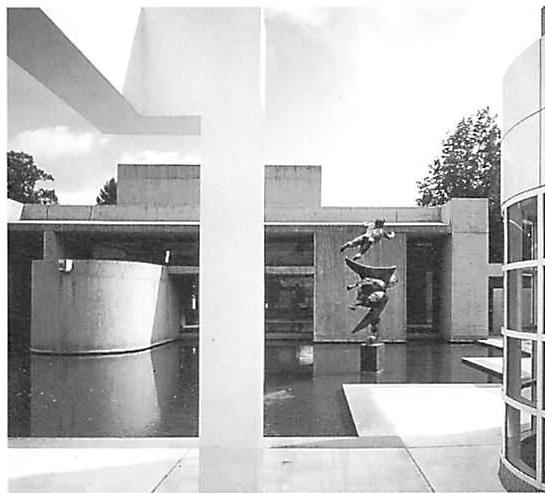

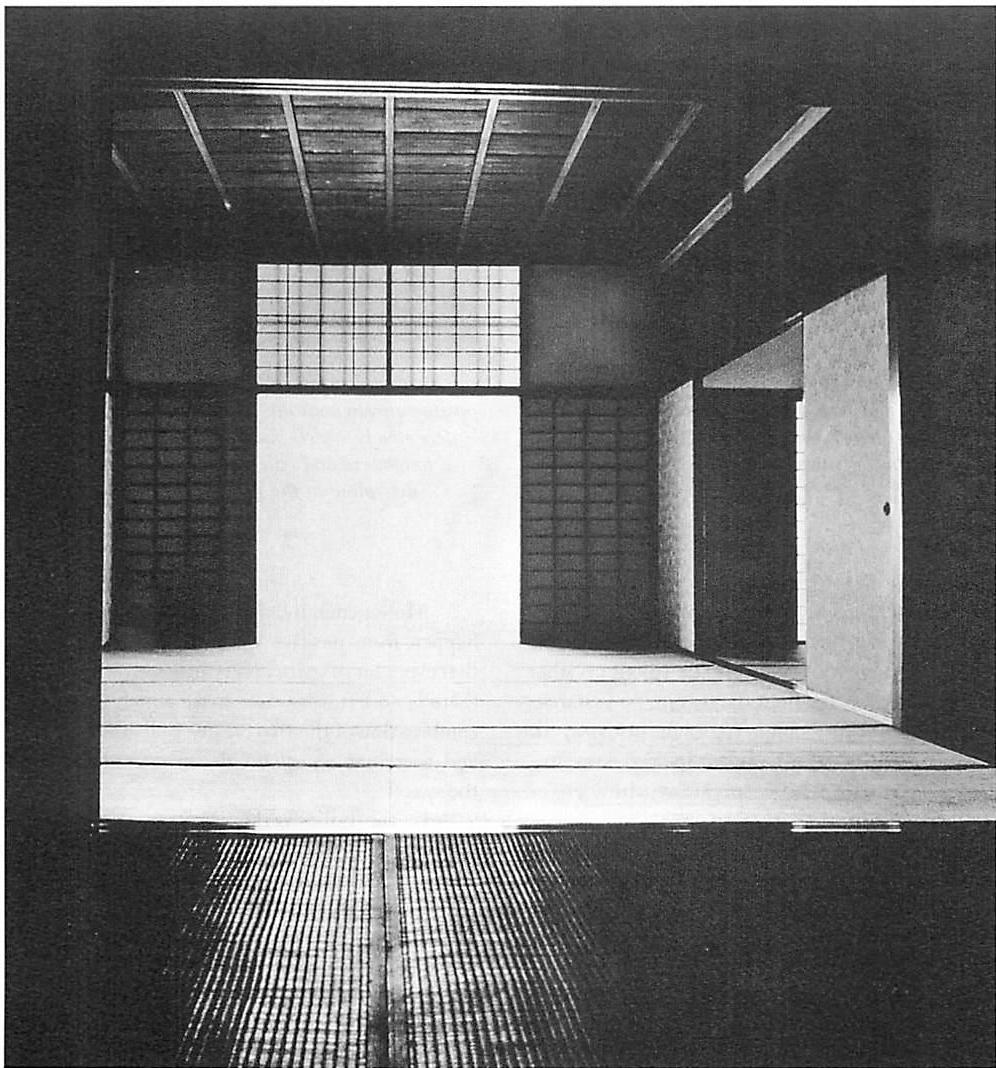

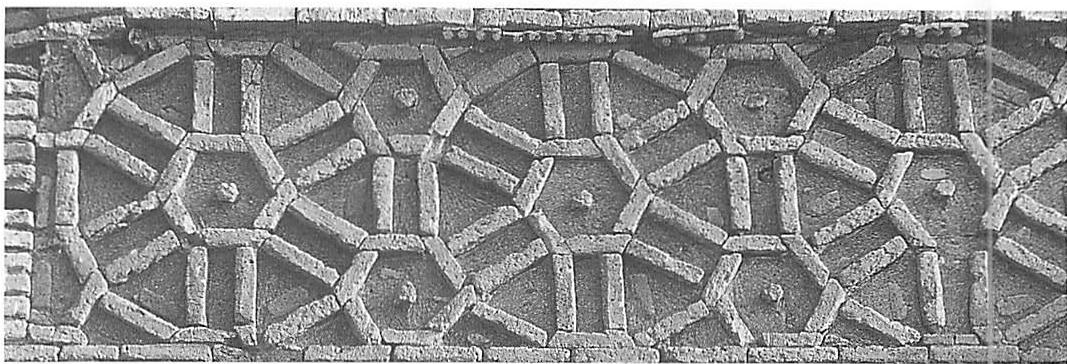

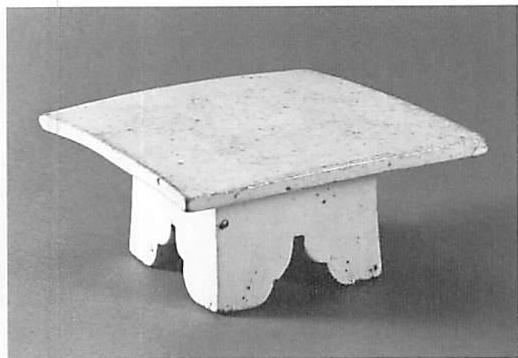

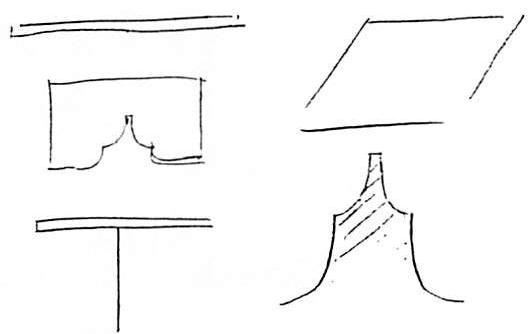

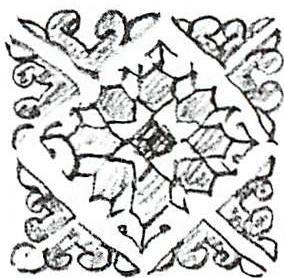

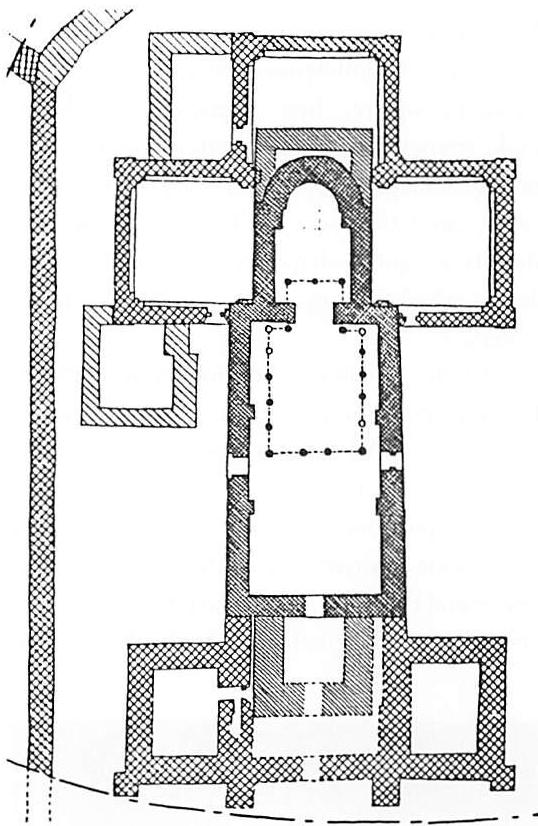

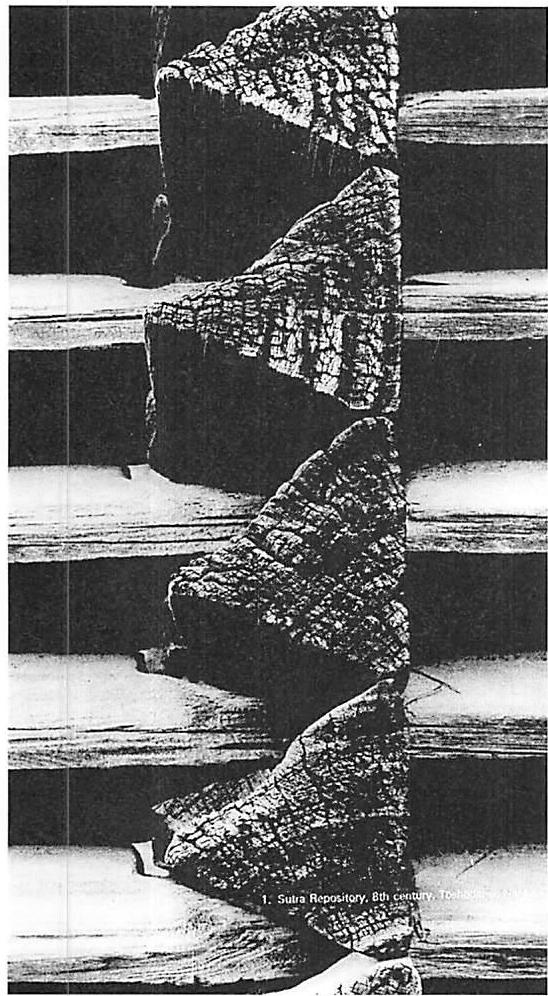

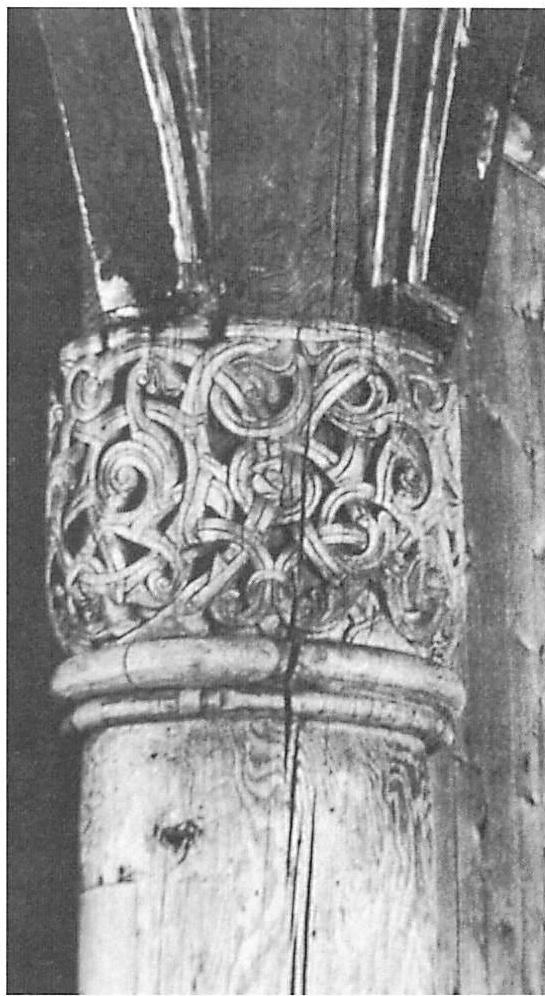

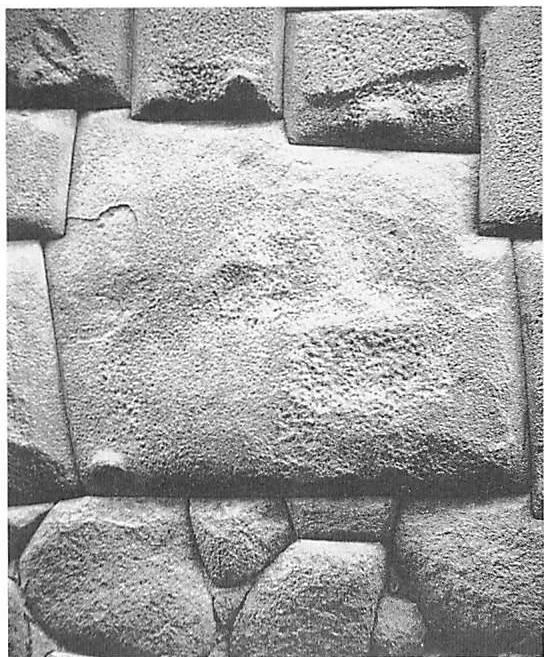

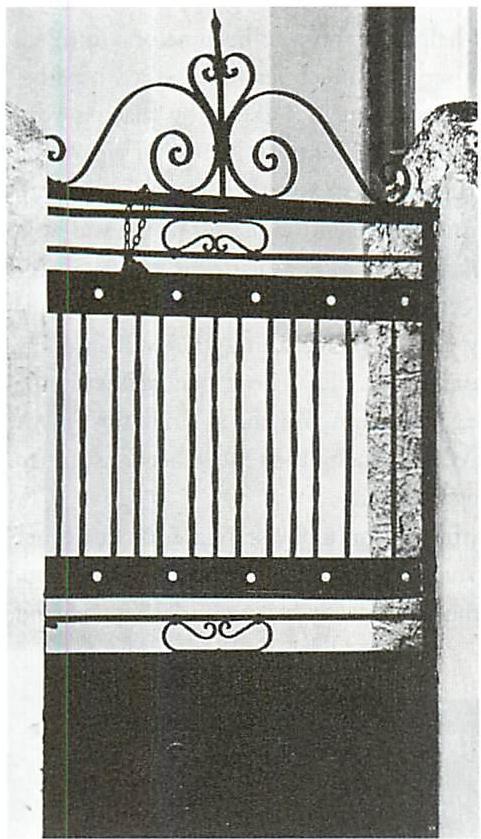

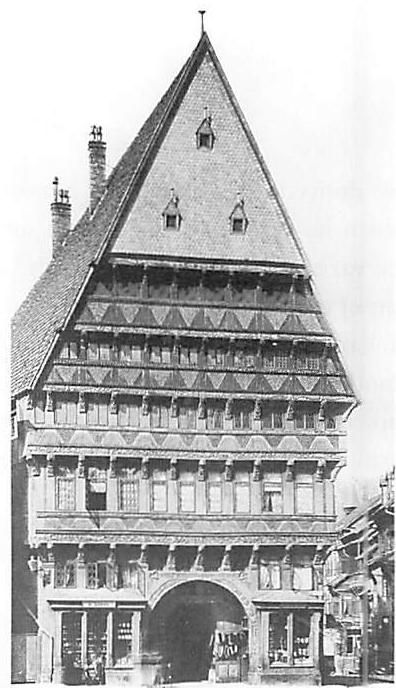

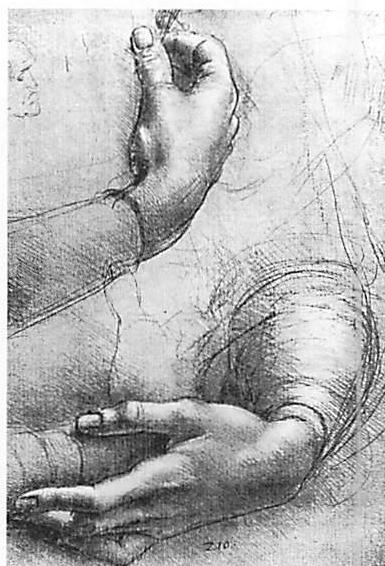

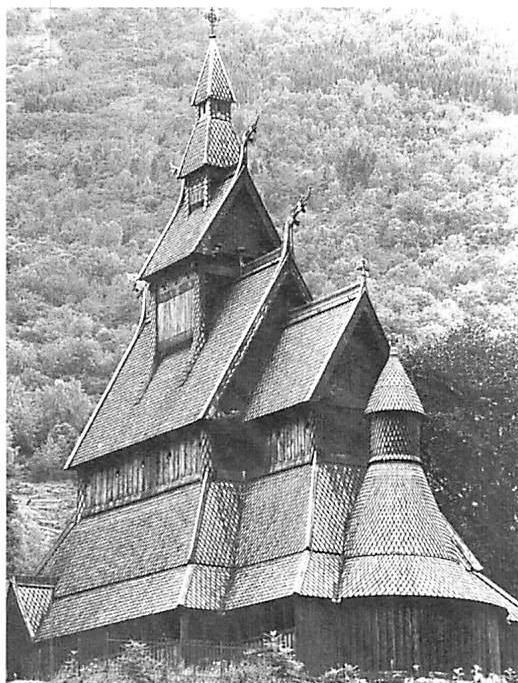

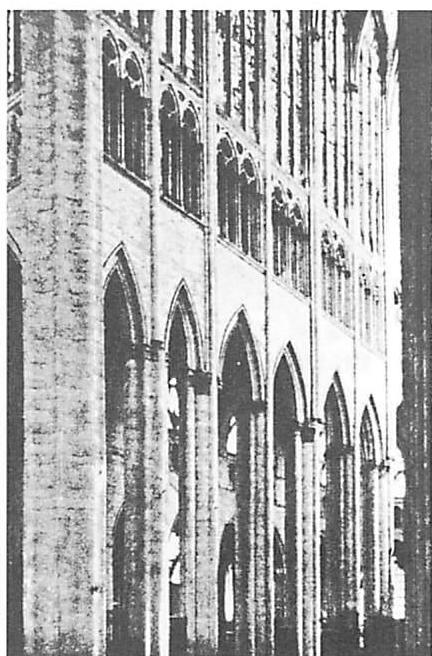

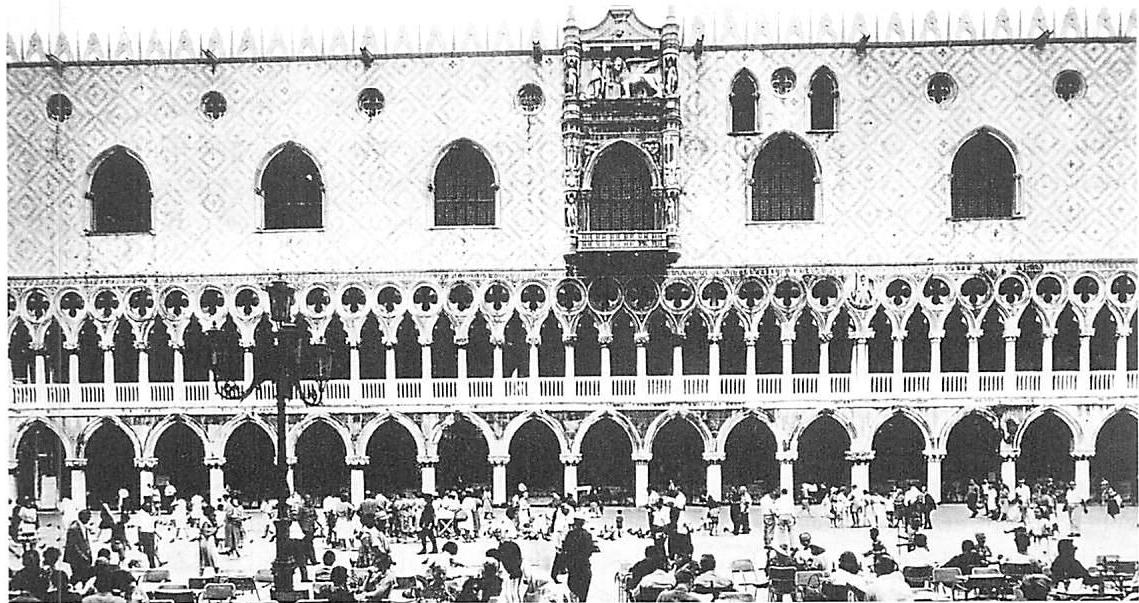

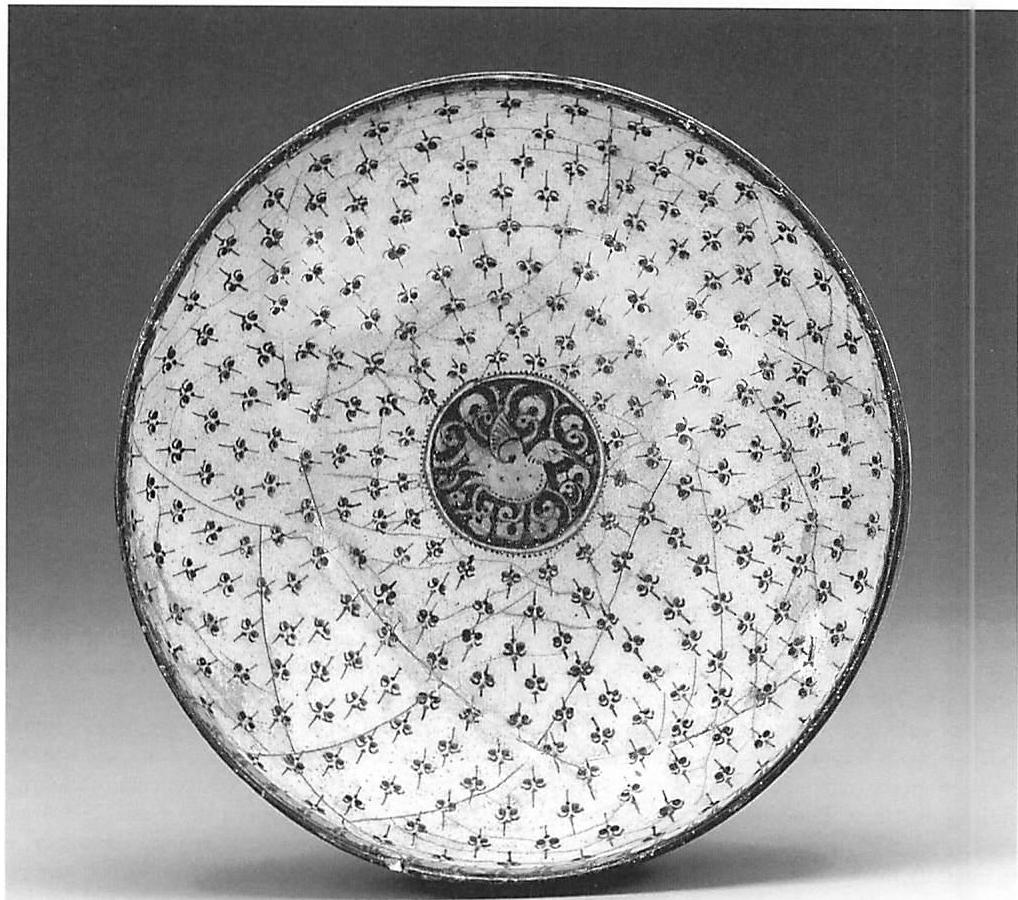

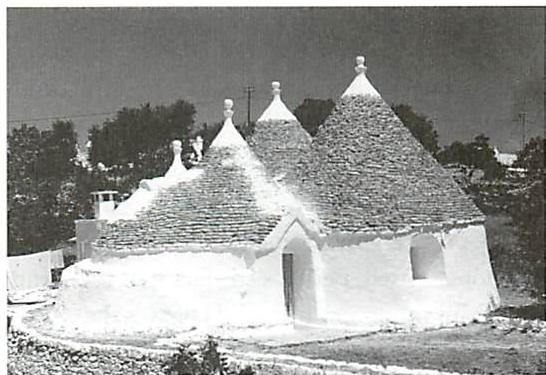

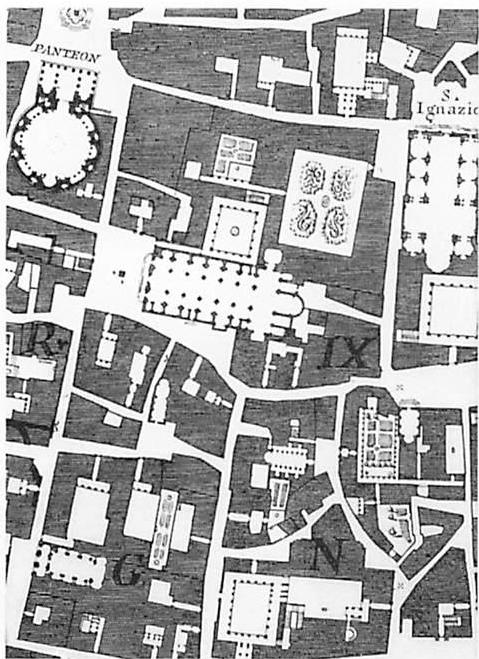

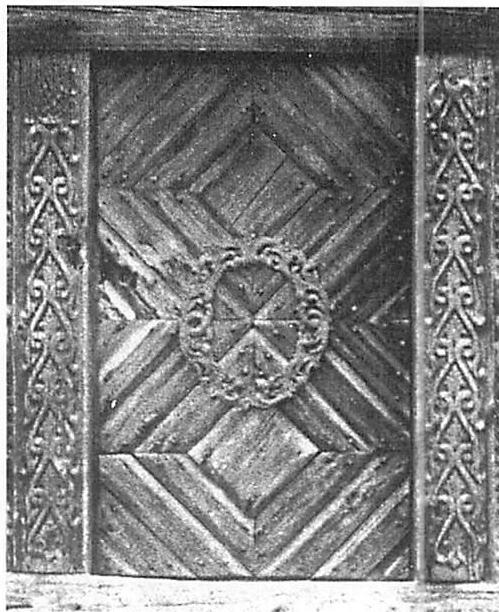

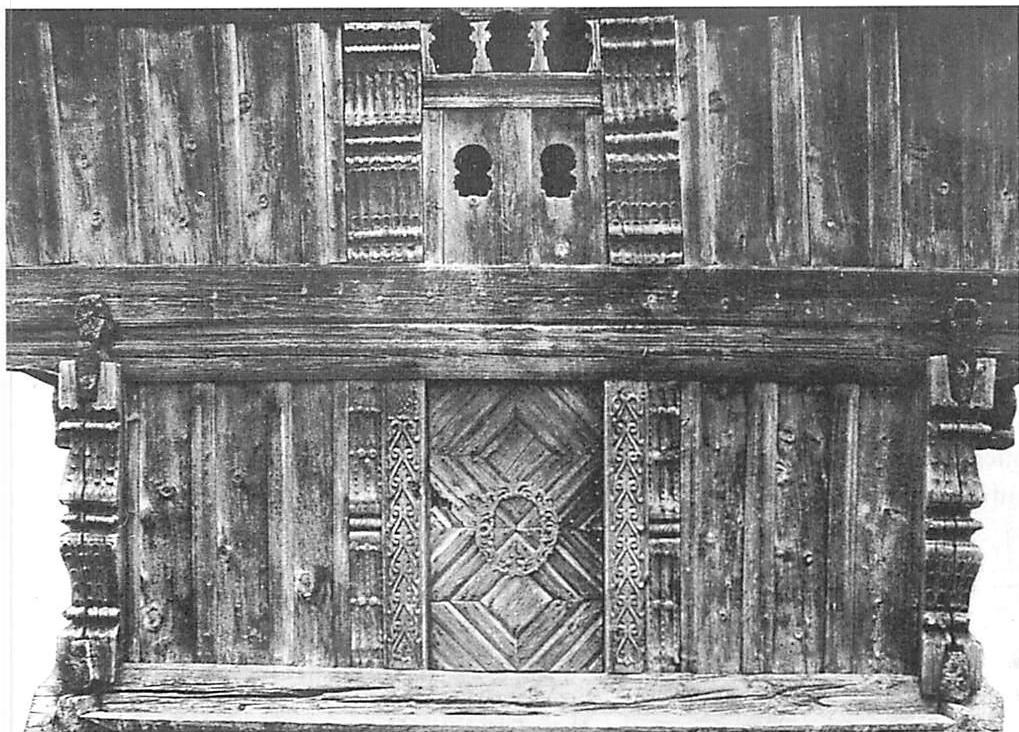

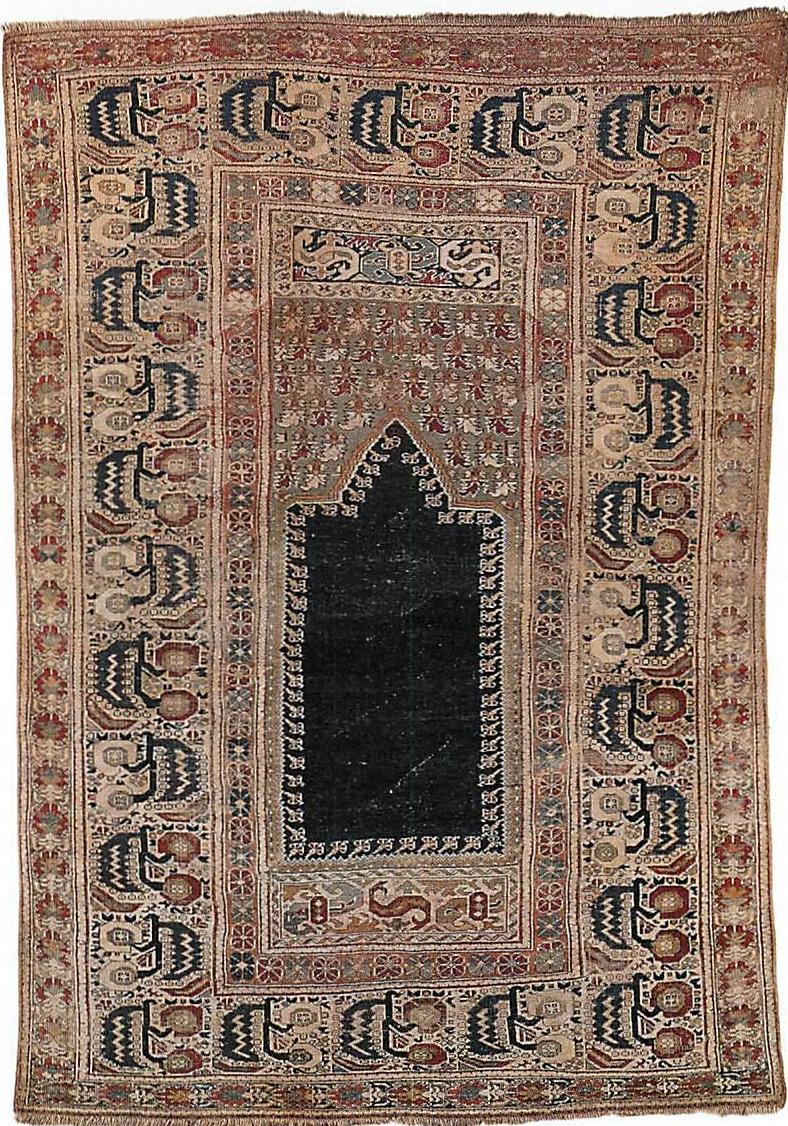

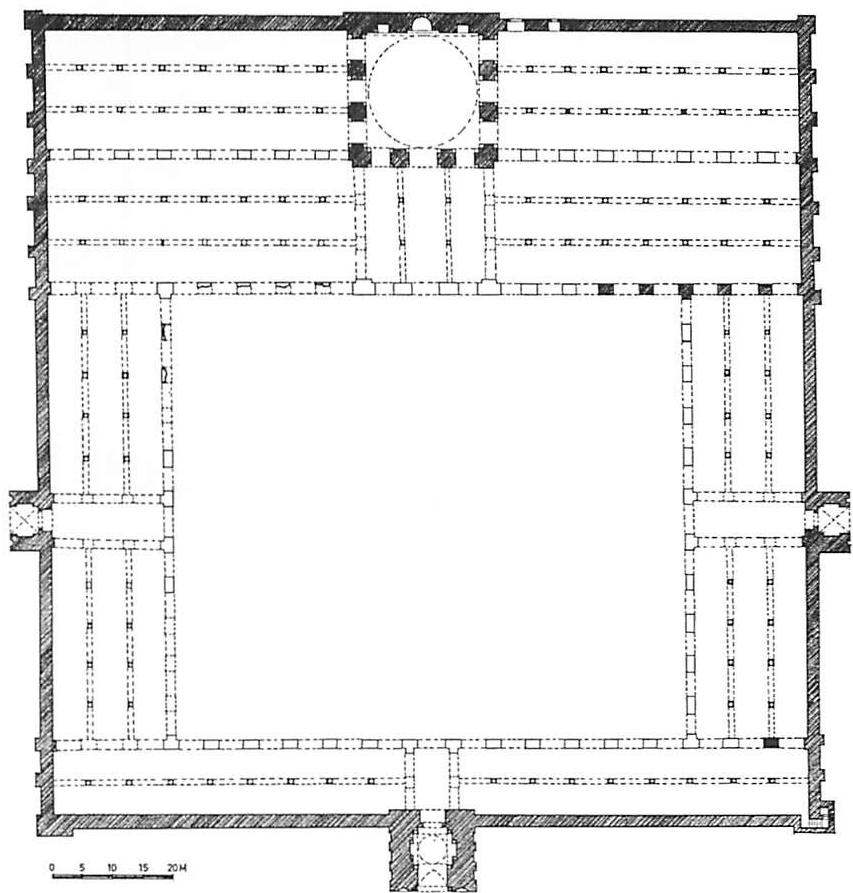

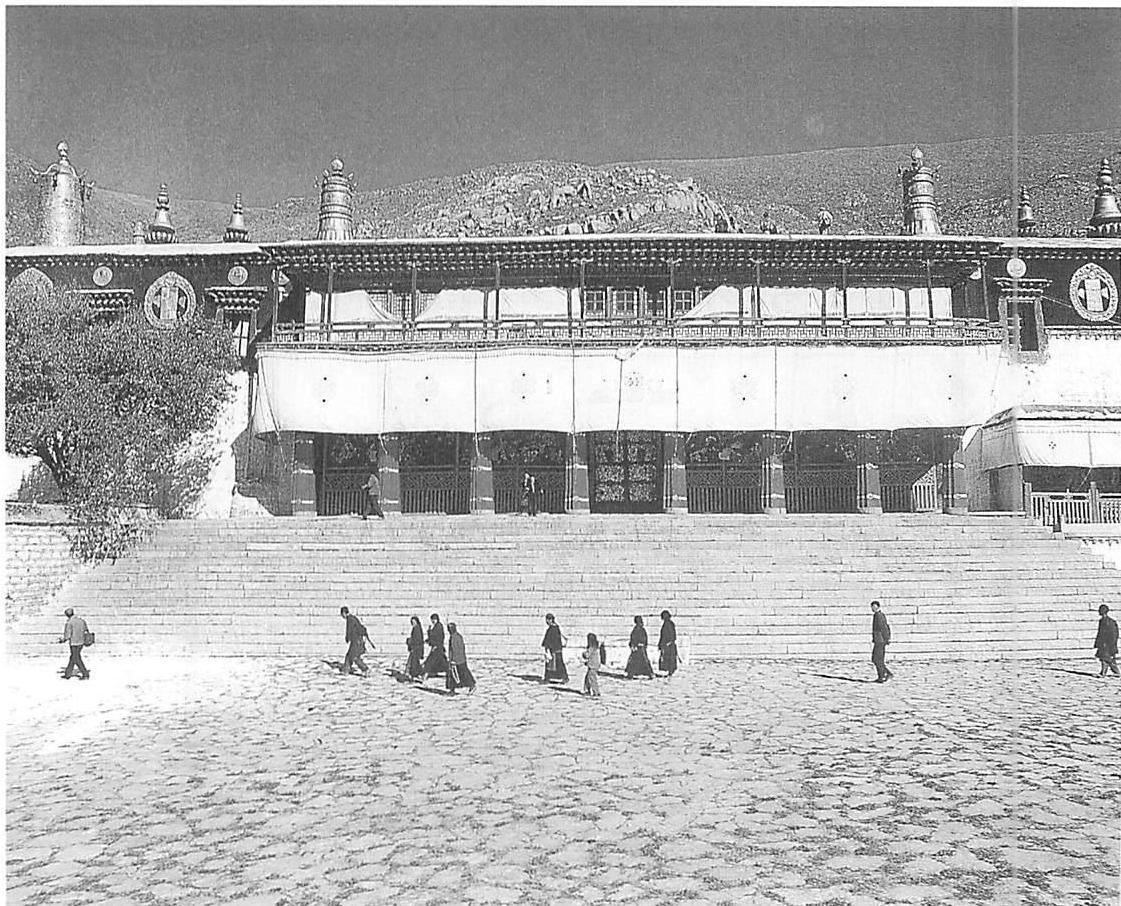

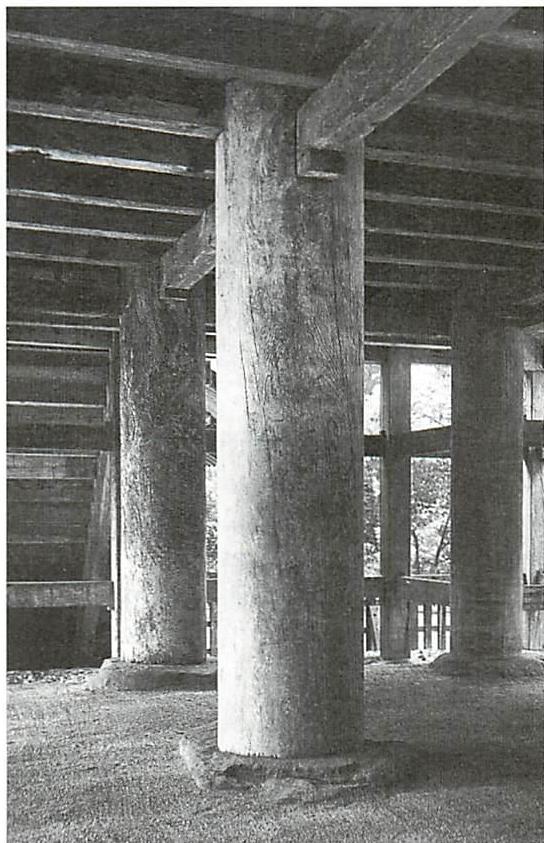

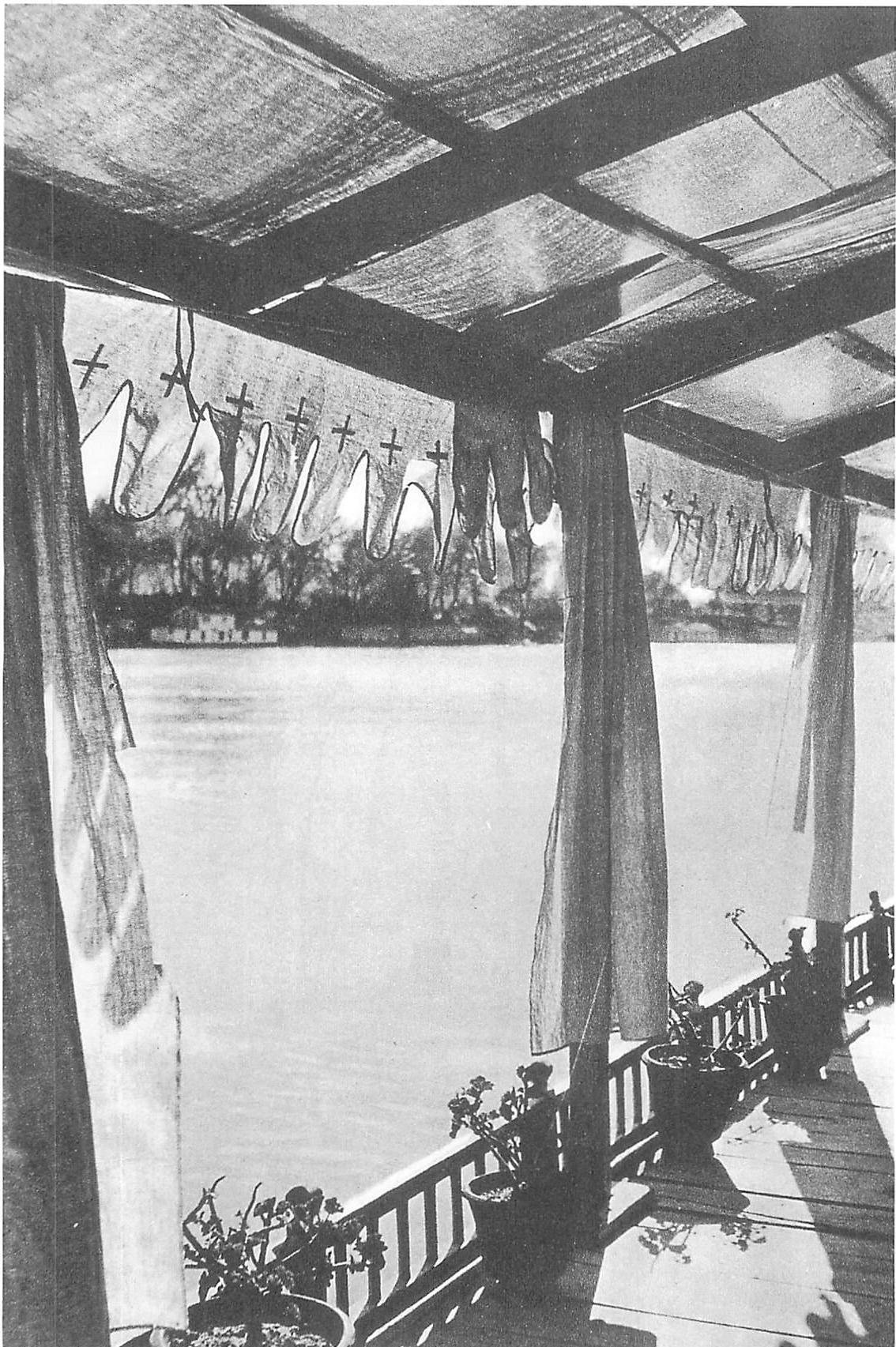

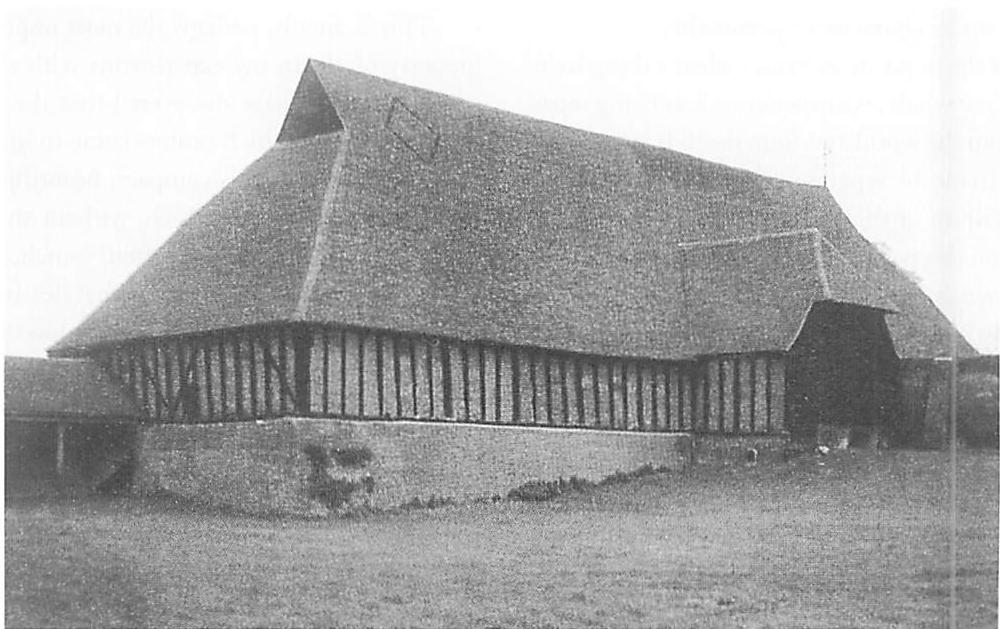

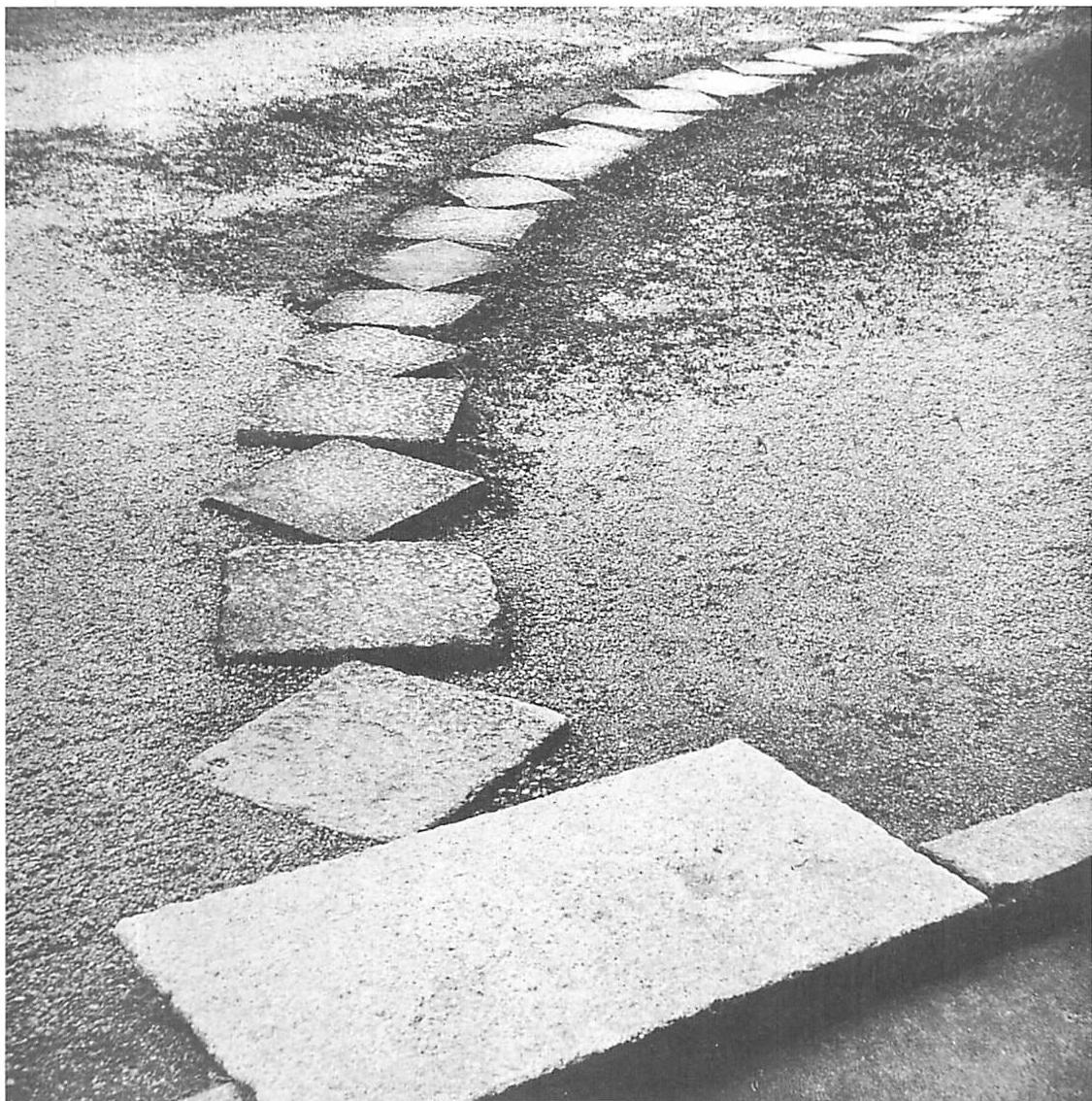

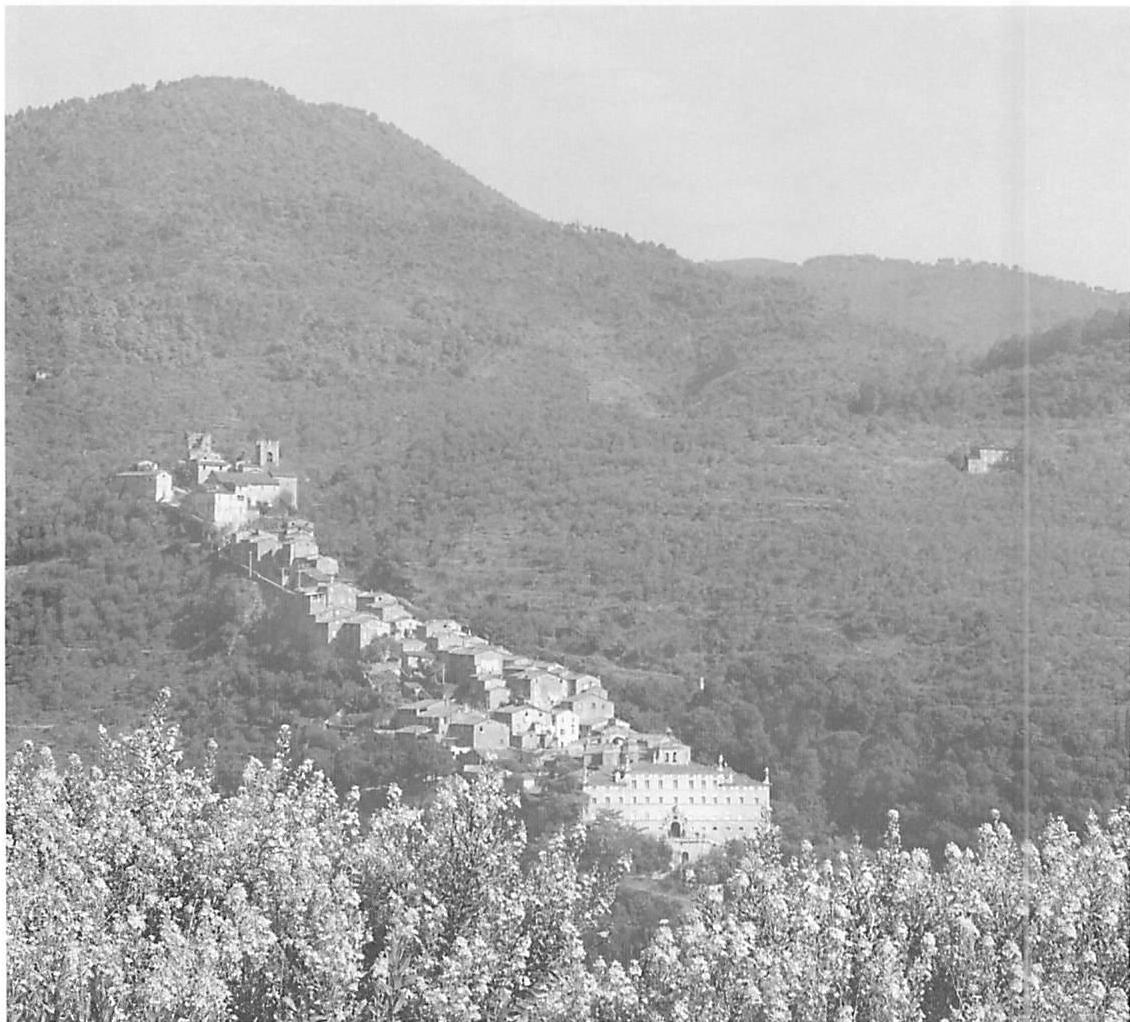

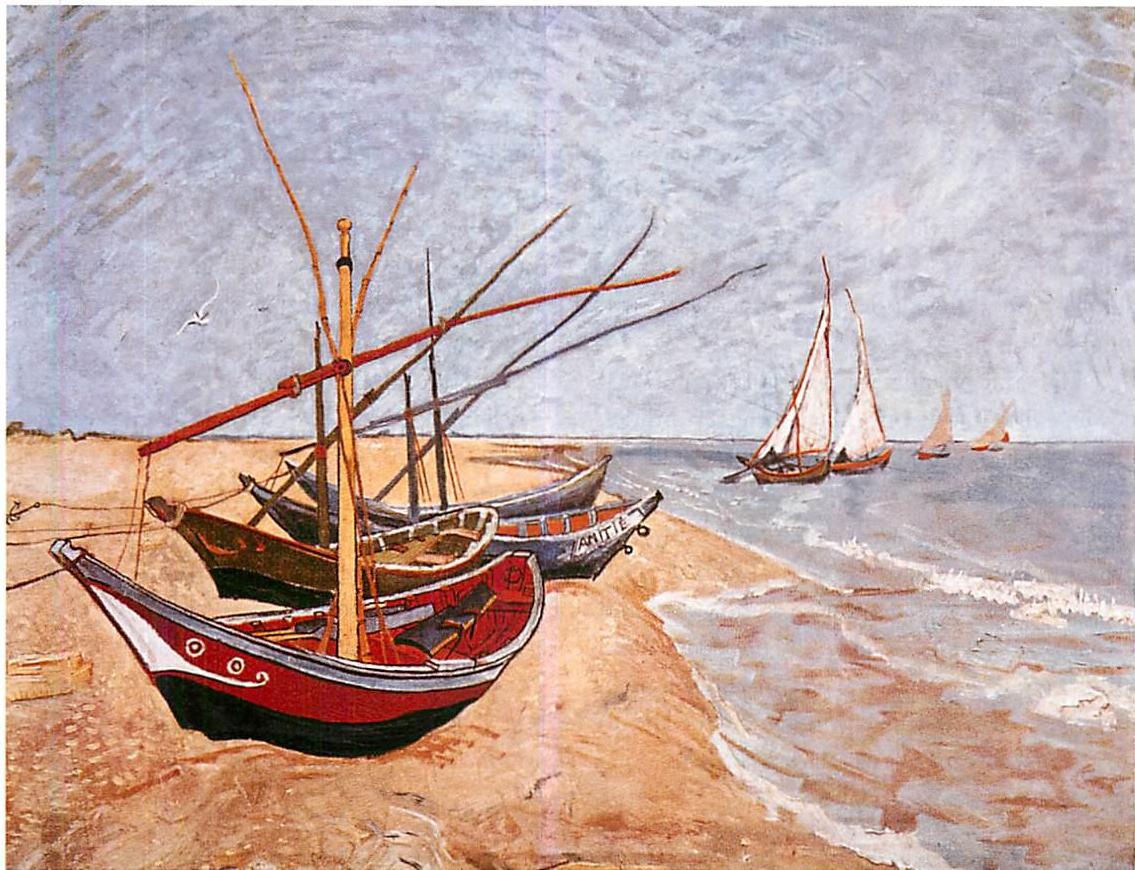

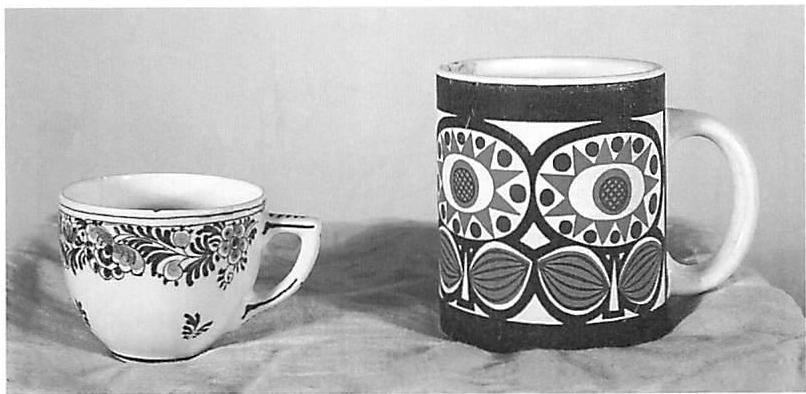

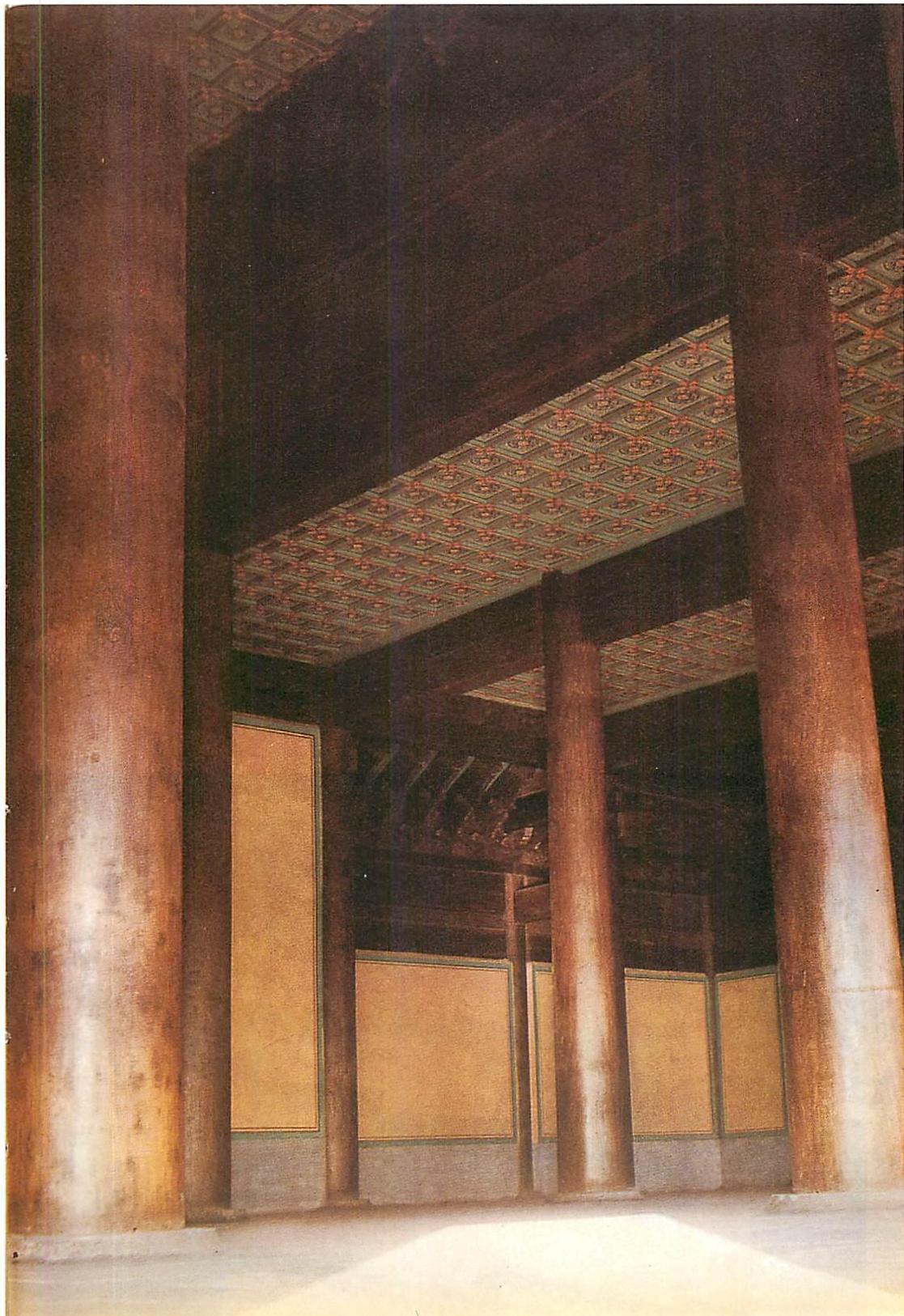

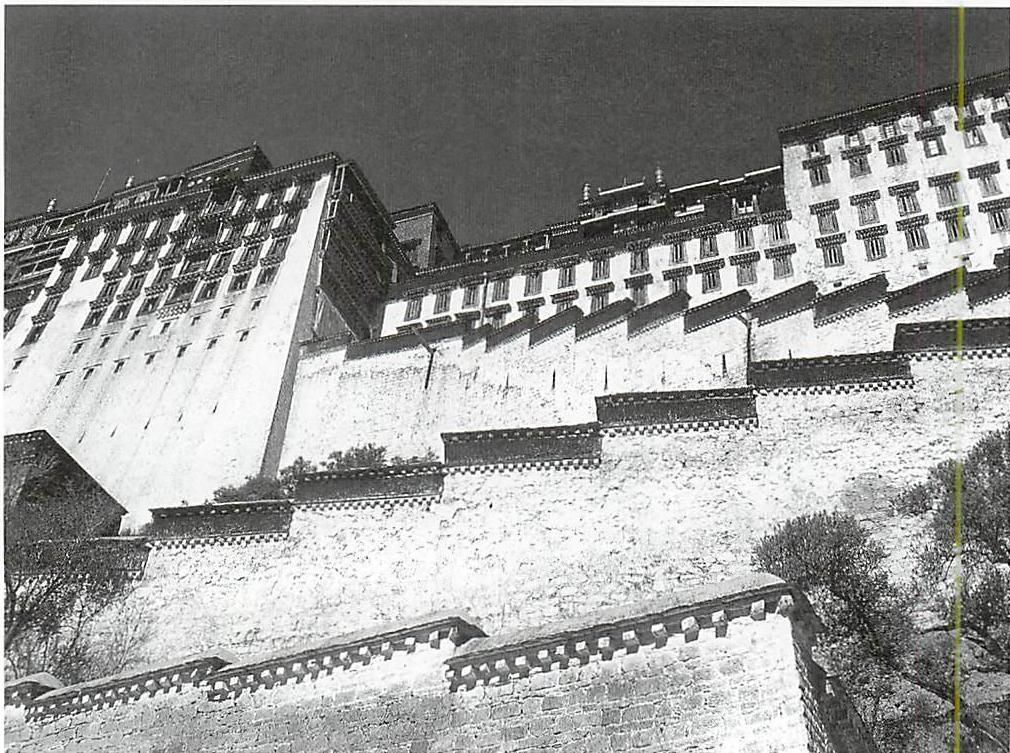

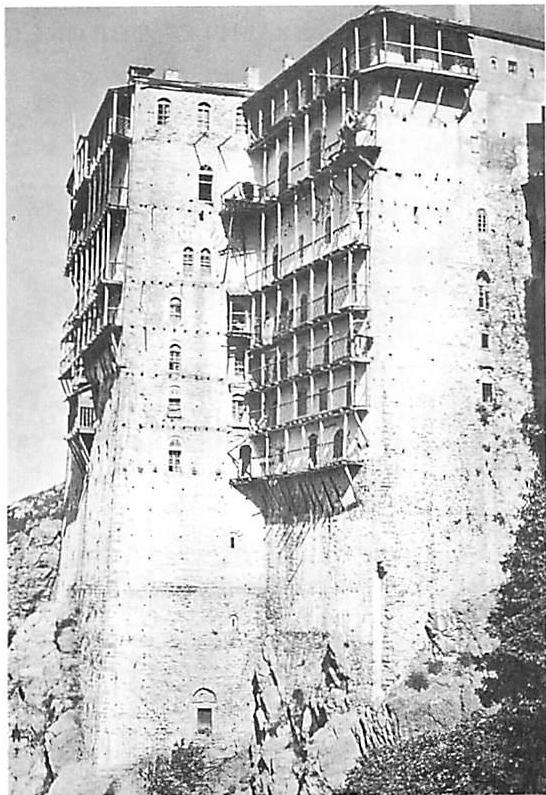

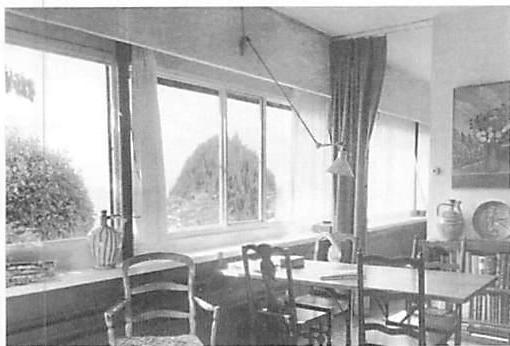

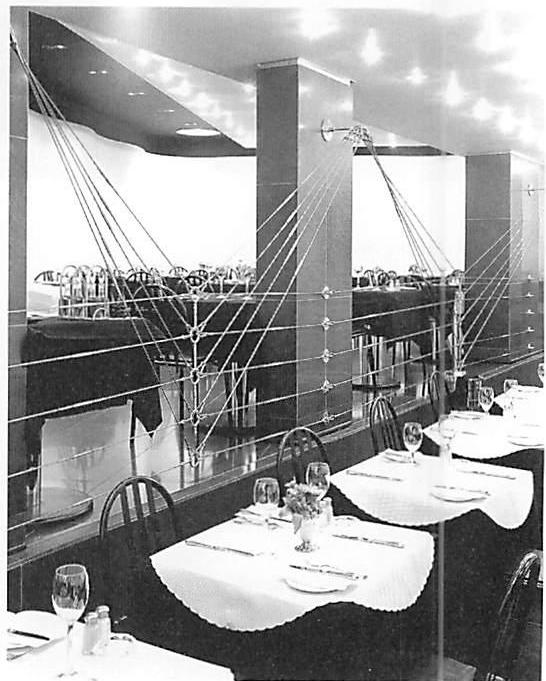

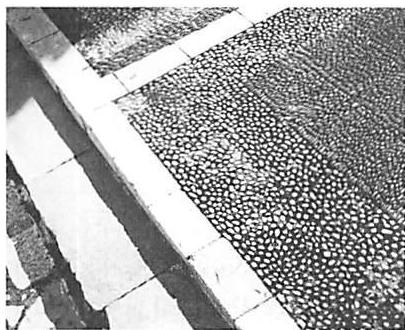

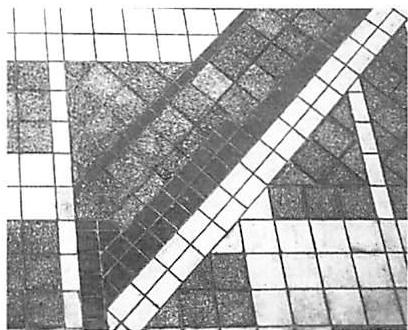

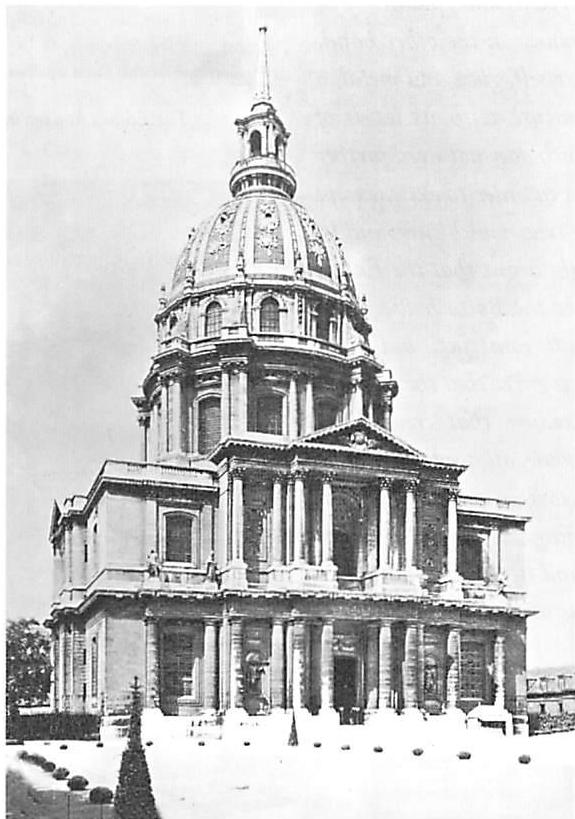

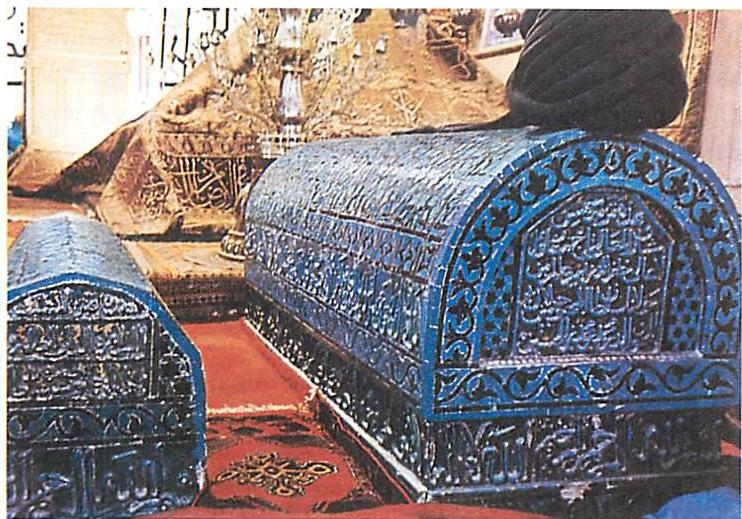

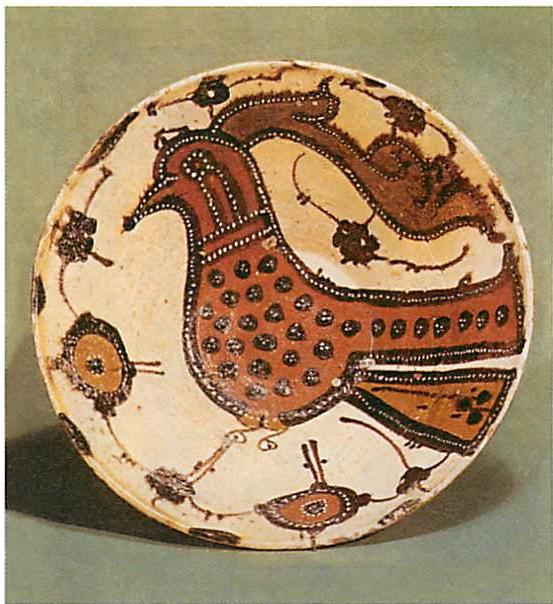

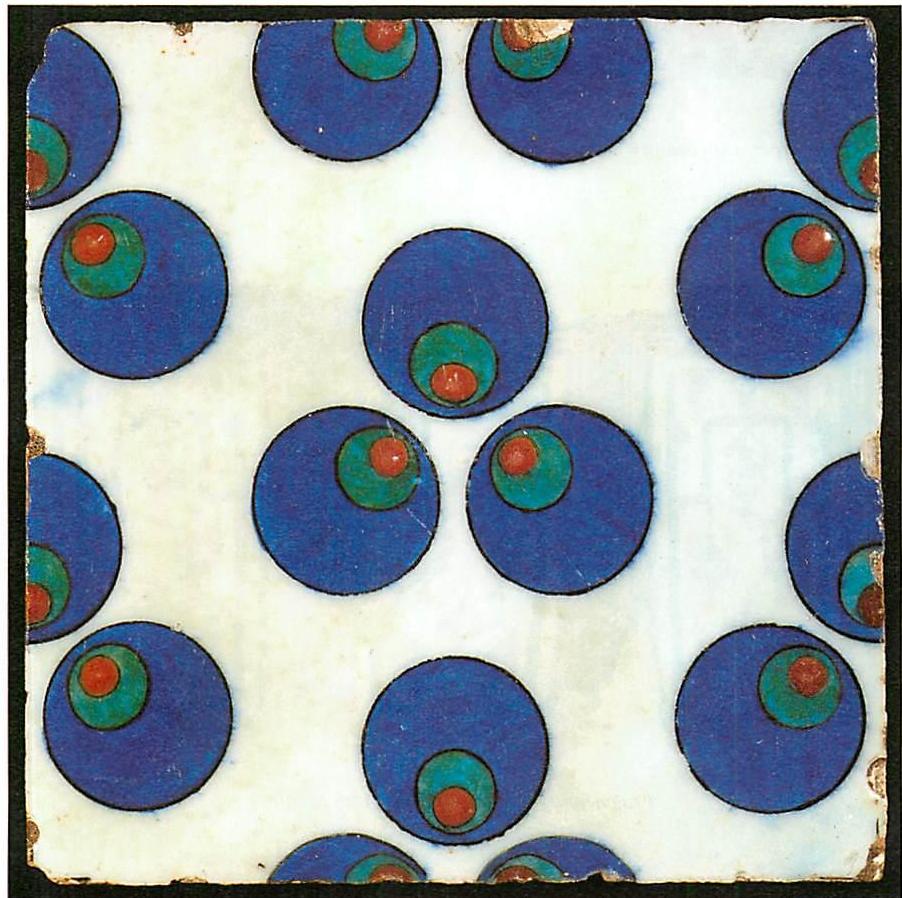

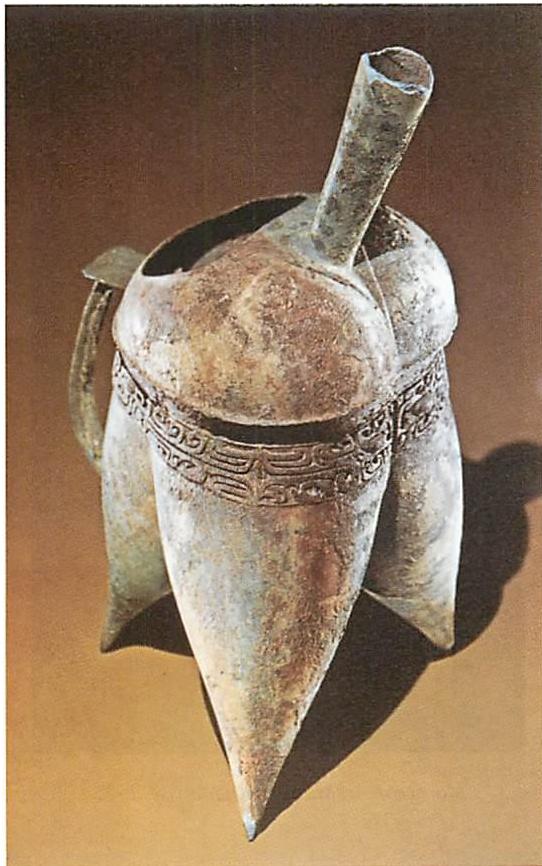

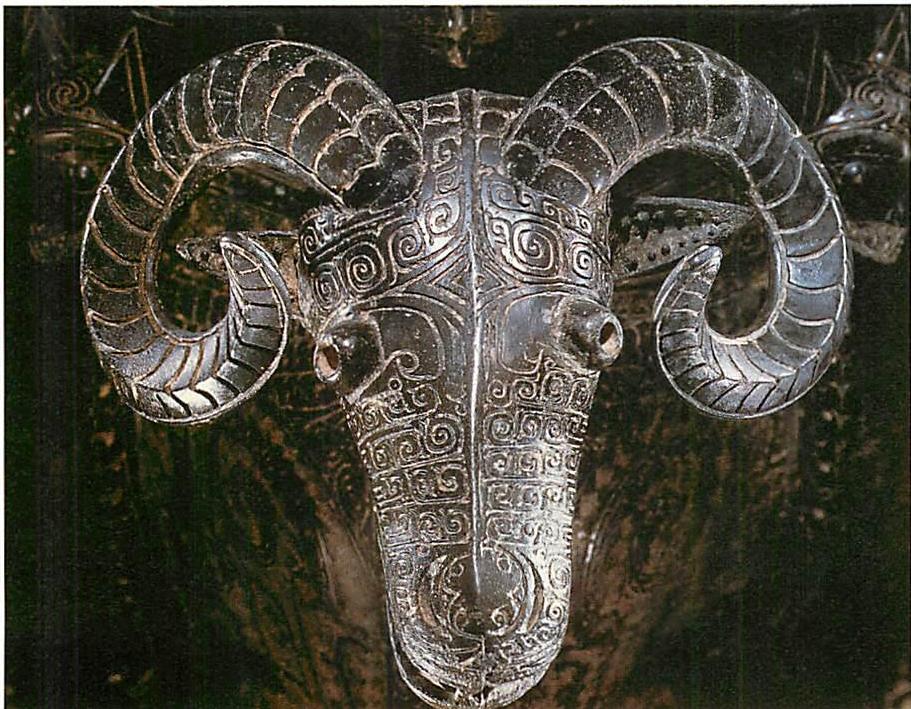

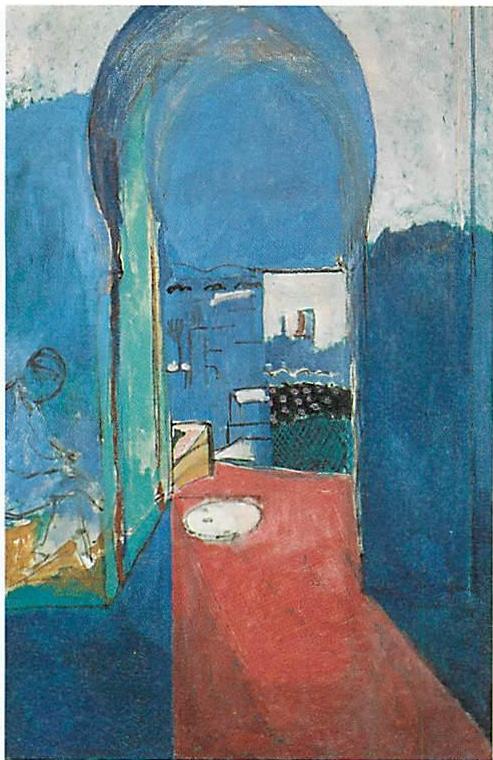

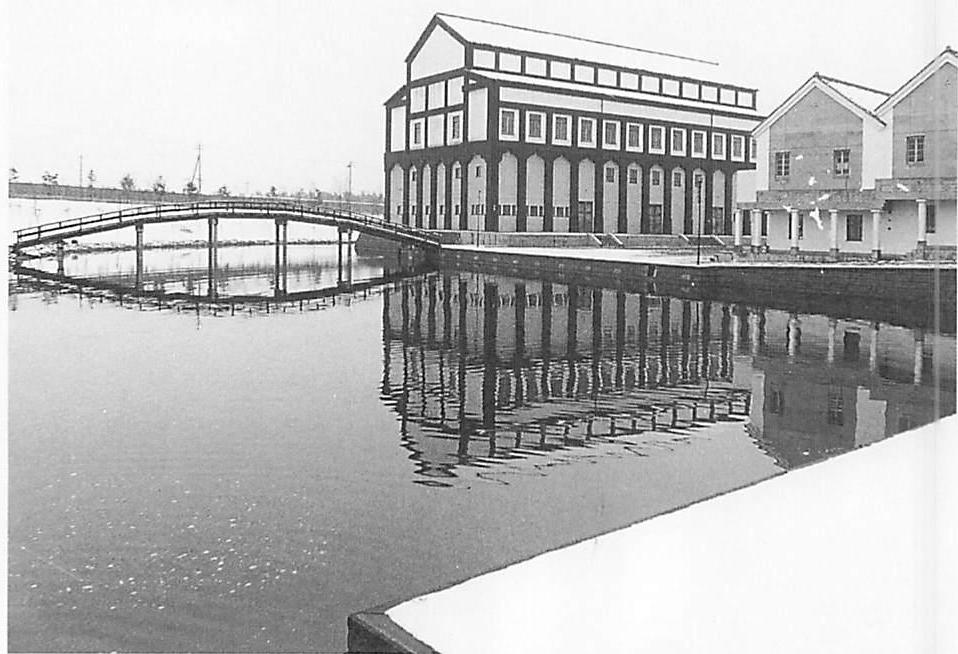

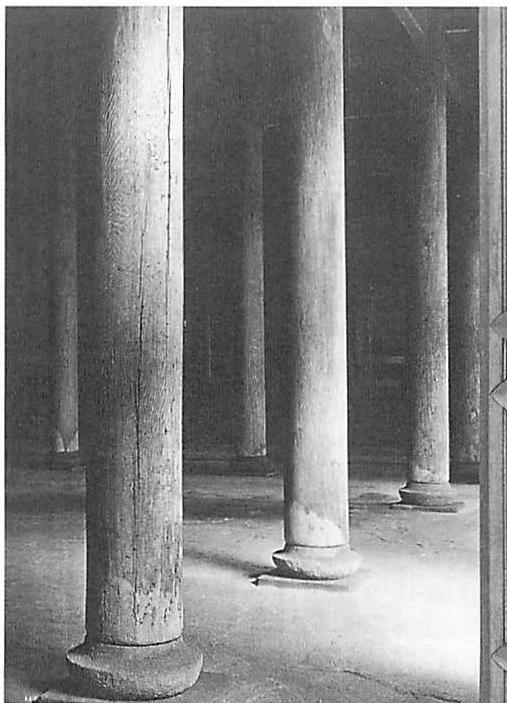

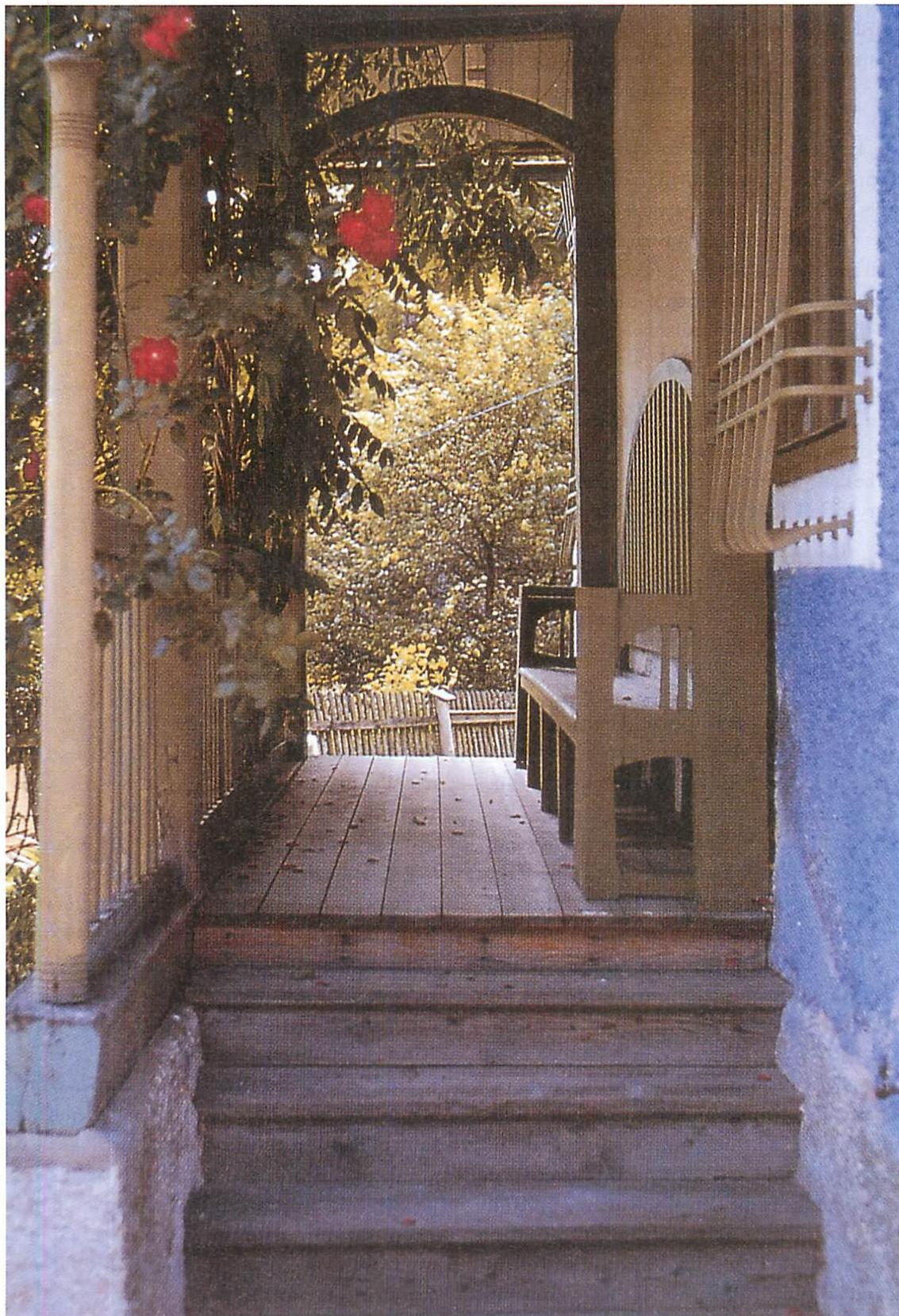

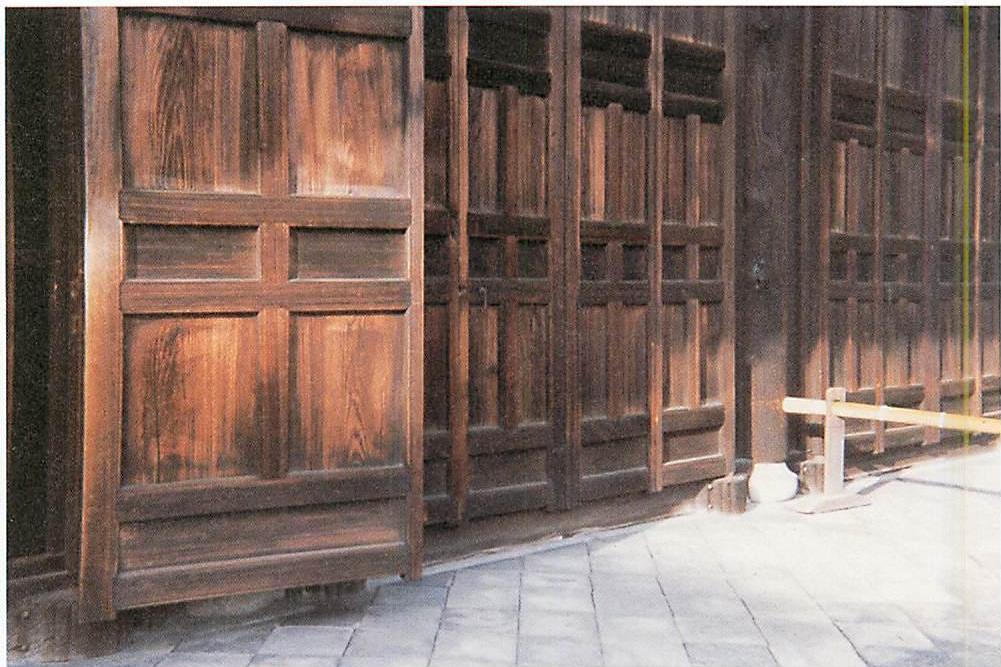

Look at the other examples of buildings on pages 12-13. Each has some kind of profound order. But within our present limited worldview we cannot describe this order scientifically. Do we even understand what their makers were trying to do? The beautiful smooth columns from Ise have an immensely subtle order, where a few ropes and small pieces of white cloth utterly change the building. The tomb of Timur has a magnificence which comes from its high body, and the fluting on the dome. These buildings move us, and touch us in our hearts. In a more modern form, the steel base of the Palm House at the Berlin Botanical Garden has a similar quality. The steel plates and bolts are very harmonious, perfectly sized. It feels like

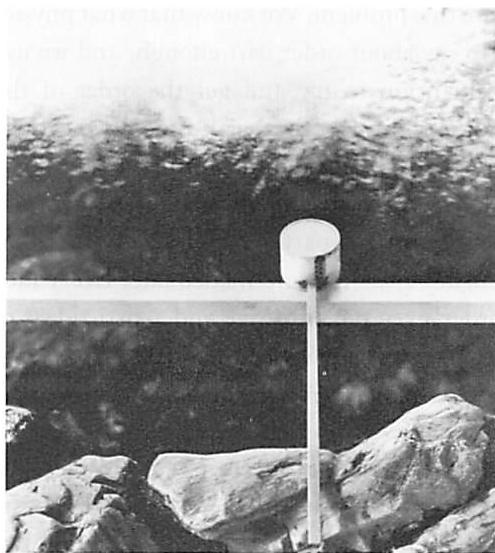

the bones of an animal. The glass and ironwork roof of the London arcade has a similar, completely naturalistic quality. And the small drinking cup, a simple piece of cut bamboo, leaves my heart pure and quiet.

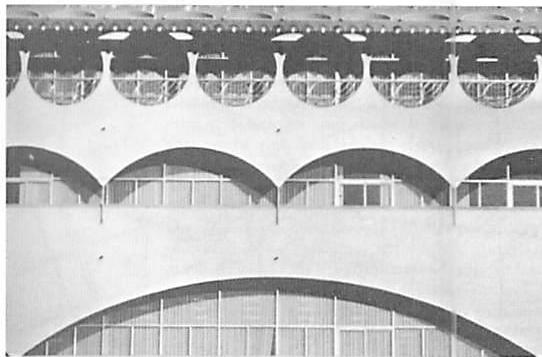

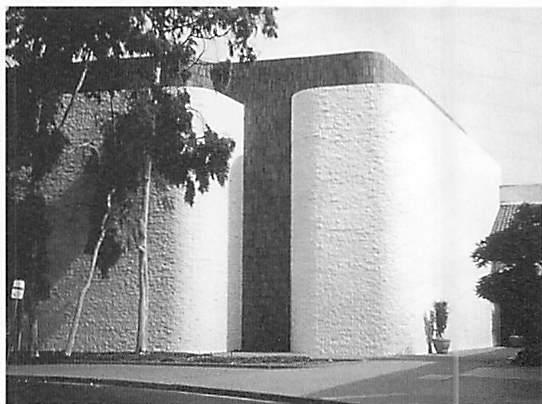

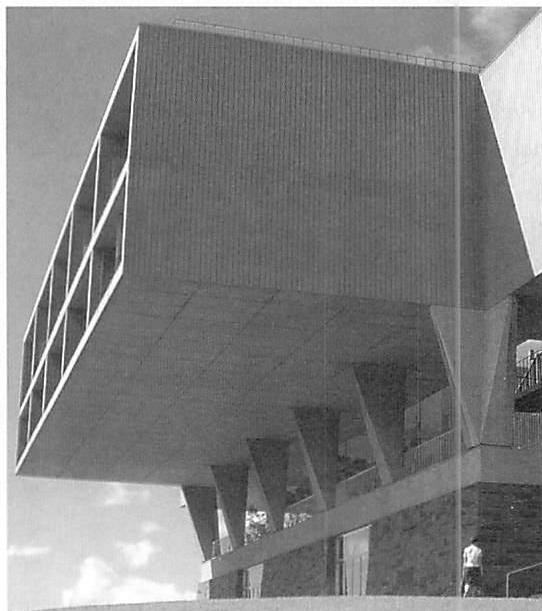

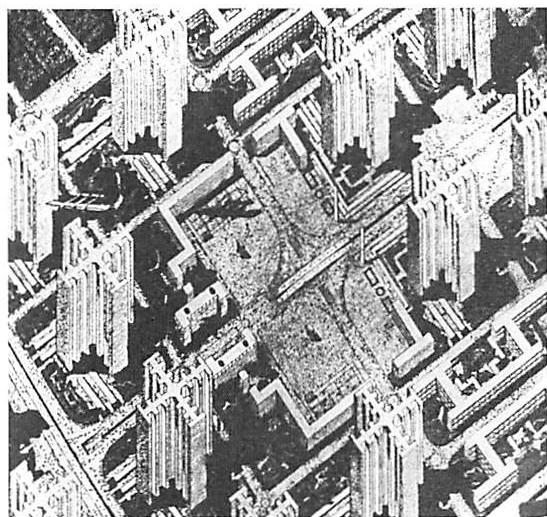

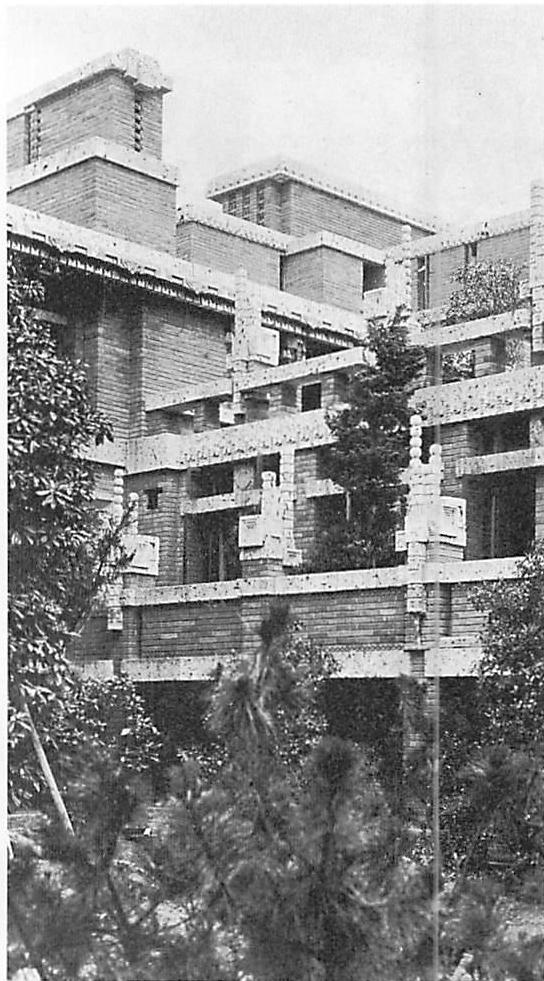

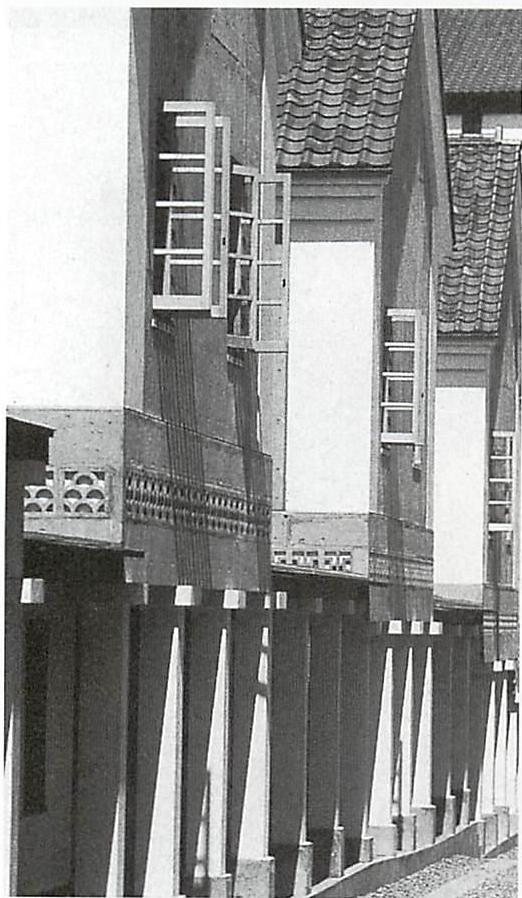

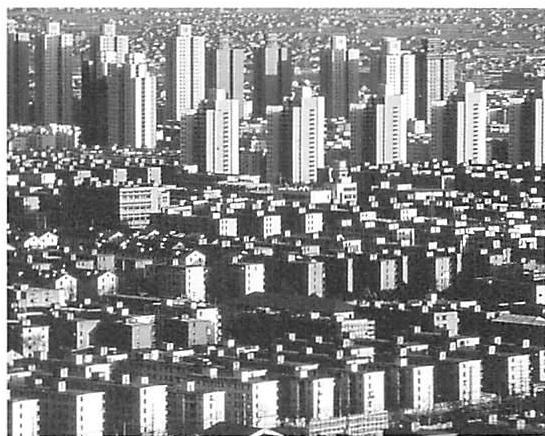

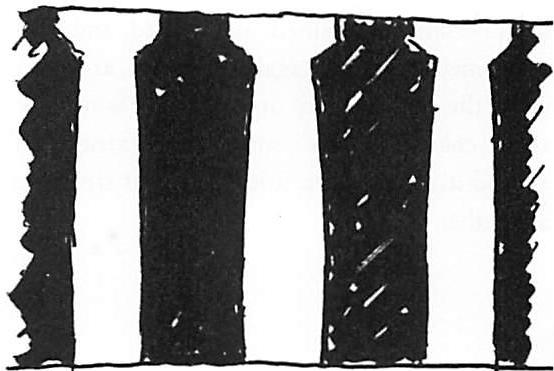

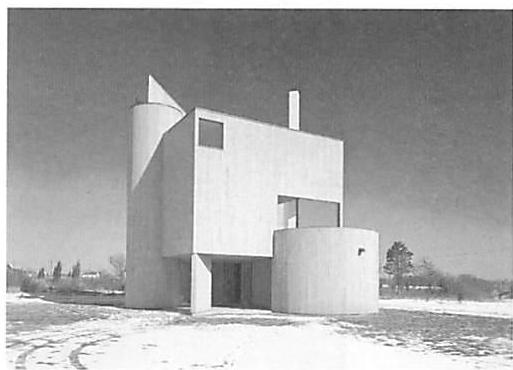

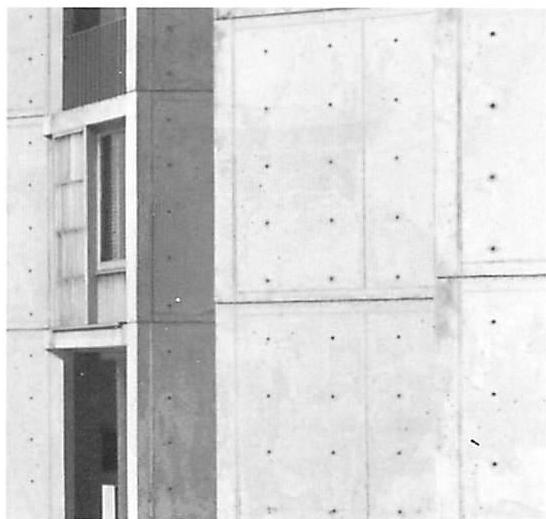

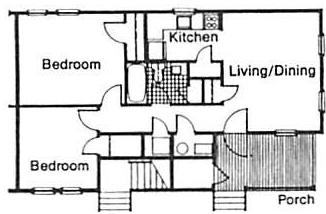

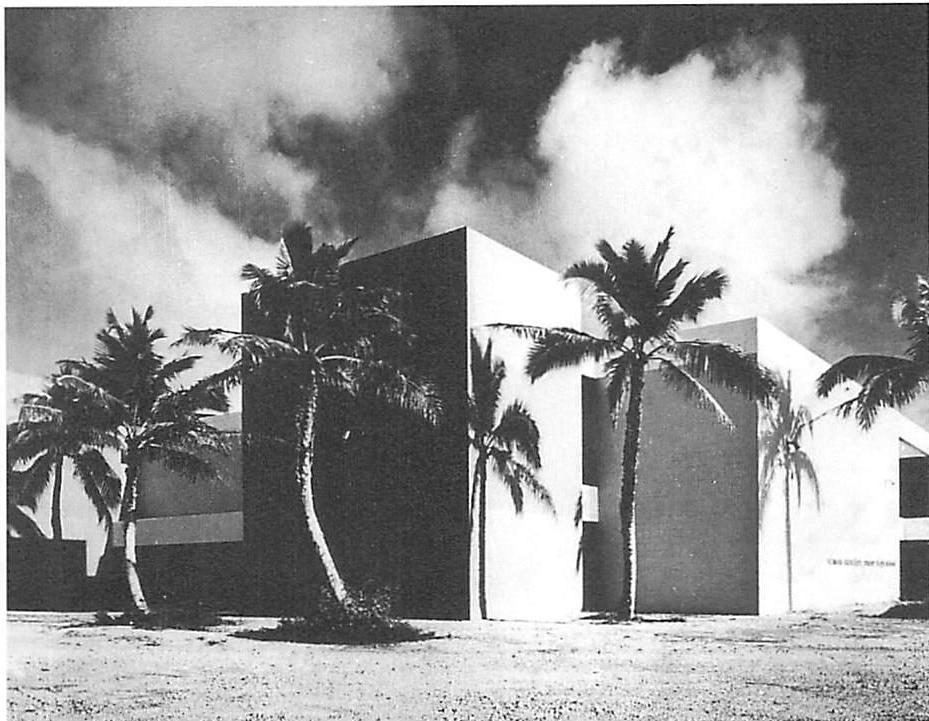

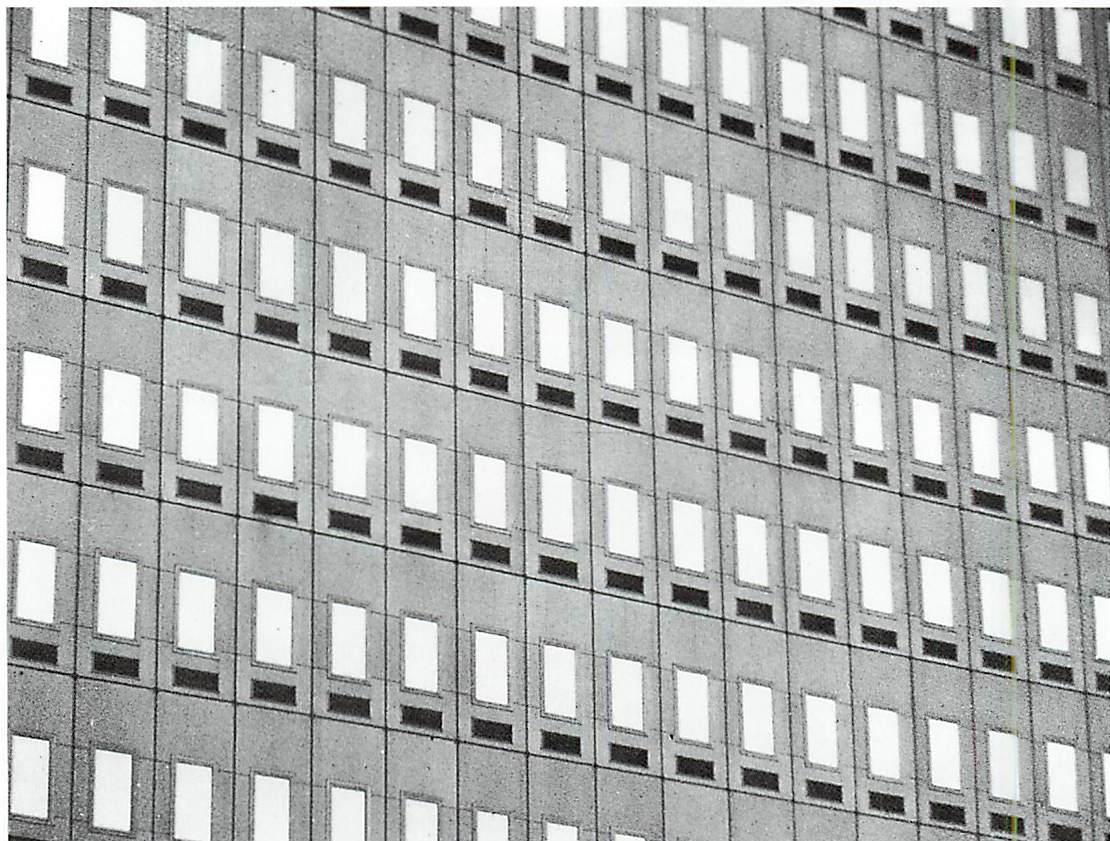

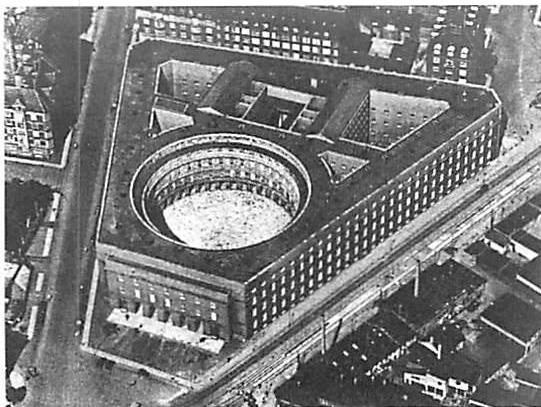

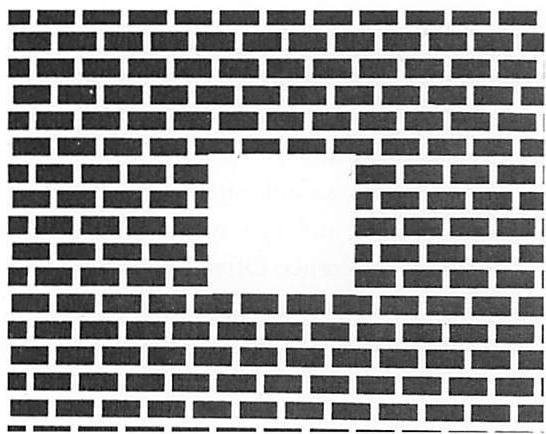

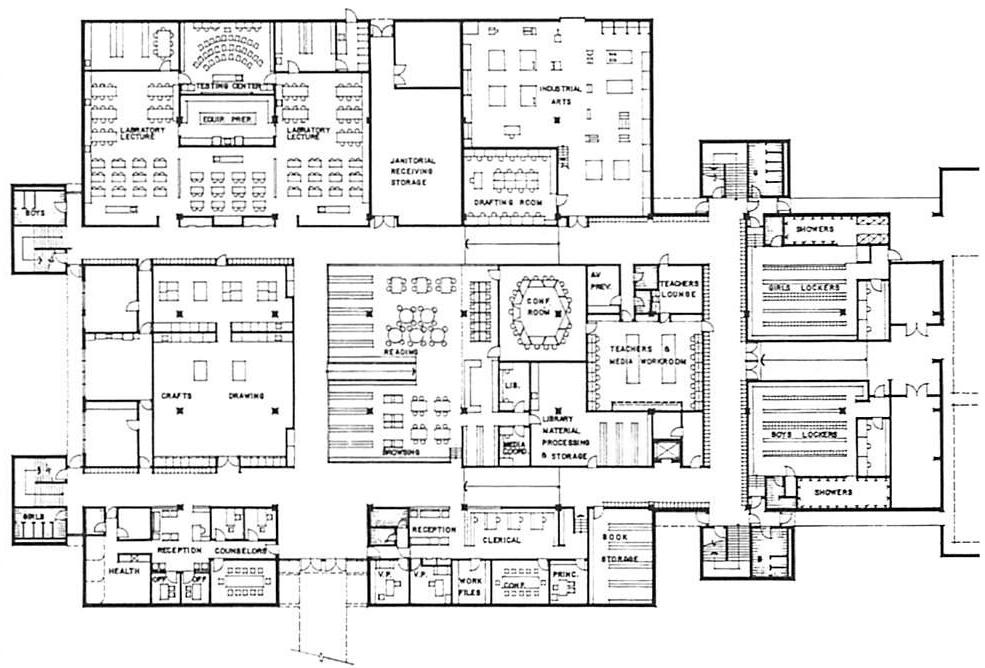

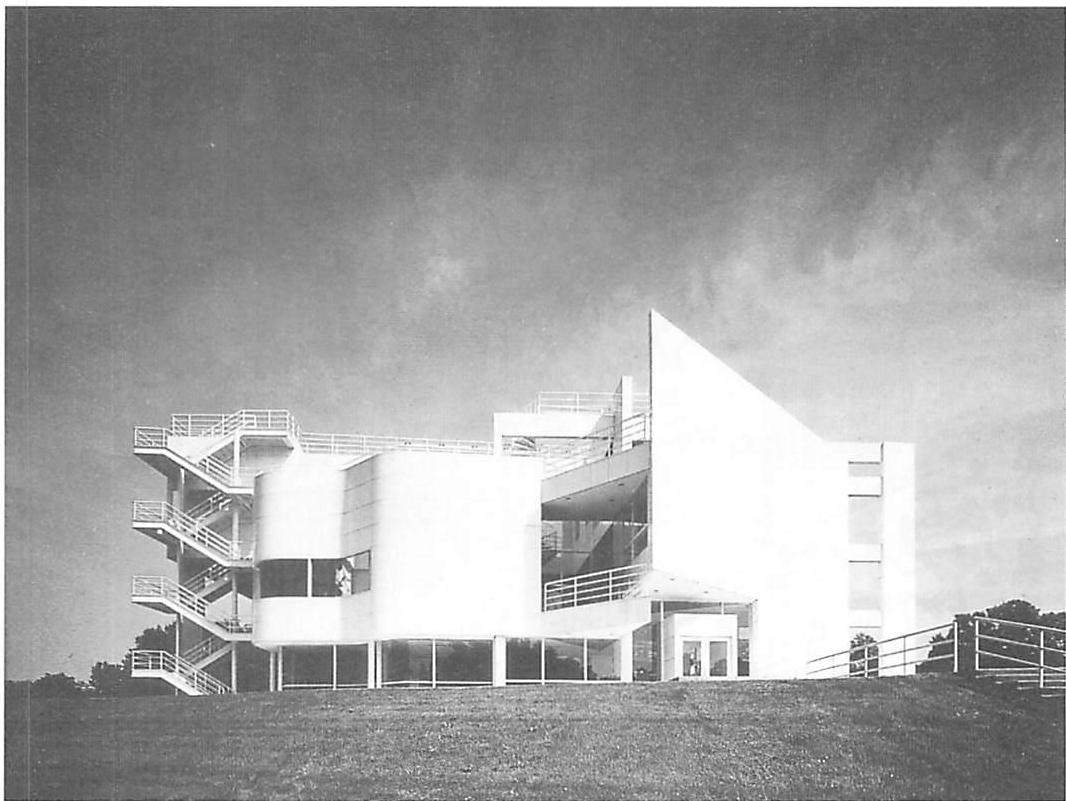

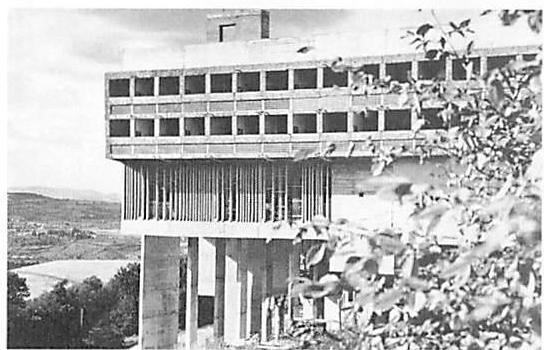

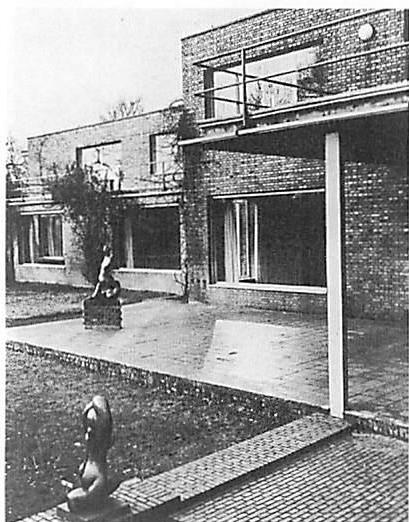

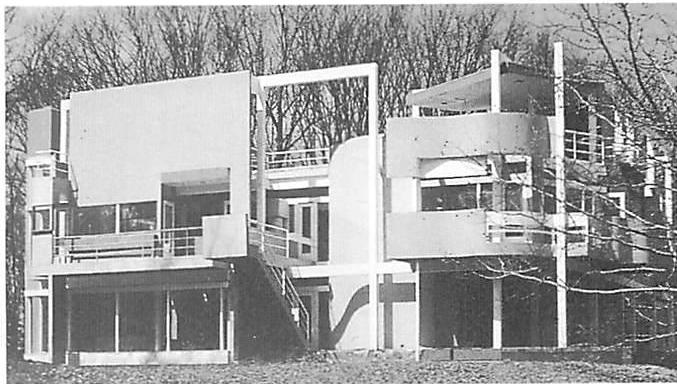

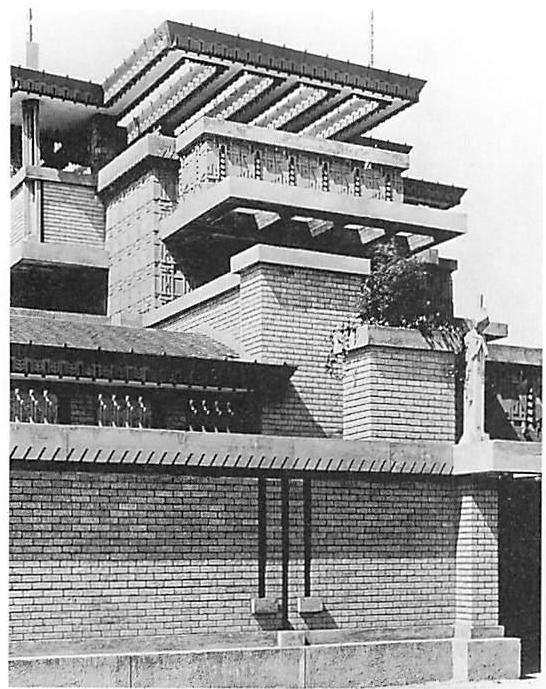

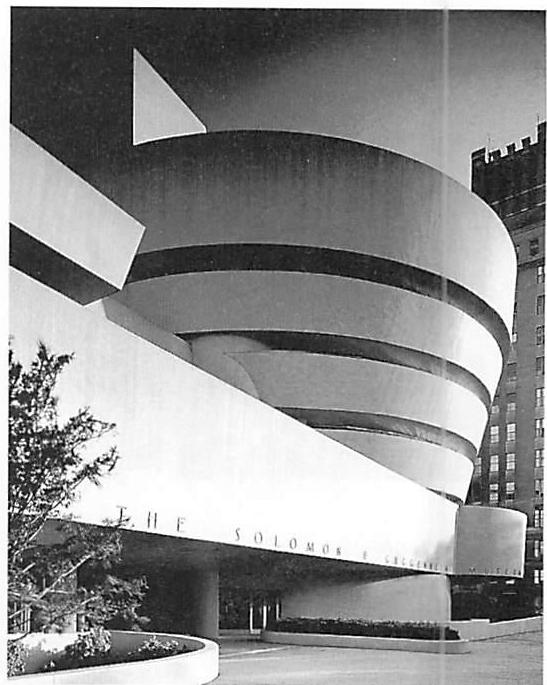

For contrast, on page 14 there are a few examples of more recent buildings. They also have order of some sort; but they are less gentle: they do not go to the heart; they are less beautiful. The apartments in Amsterdam have a brutal repetition which has little to do with the organic order of human life. The fake arches of Frank Lloyd Wright's Marin County Civic Center in California are purely decorative: they have little to do with the profound sense of order we feel in something that is structurally real. The bank building of white stucco is uninteresting and oversimplified. Its order, insofar as there is any, is certainly not one which reflects the actual beauty and subtlety of a large build-

ing, or of a complex human group. Eero Saarinen's war memorial building in Minneapolis is gross, brutal, and appalling.

Are these intuitions objectively verifiable? Is there actually less order in these later examples than in the earlier examples? Or is it just a different order?

We feel the difference in order between the examples on pages 12–13 and the examples on page 14. But can we understand this difference objectively? Are these apparently crude examples really more crude than the other examples? Is the order of the Ise shrine, or of the tomb of Timur the Great, genuinely and objectively more profound than the repetition of the Amsterdam apartments? What, indeed, is that thing we intuitively feel as order in all these different cases?

It is extraordinary to realize that, in the current intellectual context, not one of these questions has had a clear answer.¹⁴ Among current ideas of order, there is no conception of

order which helps us create the profound life that can exist in buildings and in other artifacts.

Of course, today, as a matter of practice, when we try to make a building we usually ignore this problem. We know that what physics has to say about order isn't enough, and we use our intuition to try and get the order of the building right. But this weak and only mechanical view of order is unlikely to go on working in the intellectual climate of the 21st century. It is not only the particular kinds of order that occur in physics that are inadequate. Every idea of order, even our intuitive and artistic ideas of order, are inadequate because they are, in my view, based on a wrongheaded foundation. It is the whole idea of order, the whole idea of what order is, as it exists in 20th-century thought, which is inadequate.

And for making things, or giving life to them, our current ideas of order are utterly inadequate.

4 / ORDER AS MECHANISM

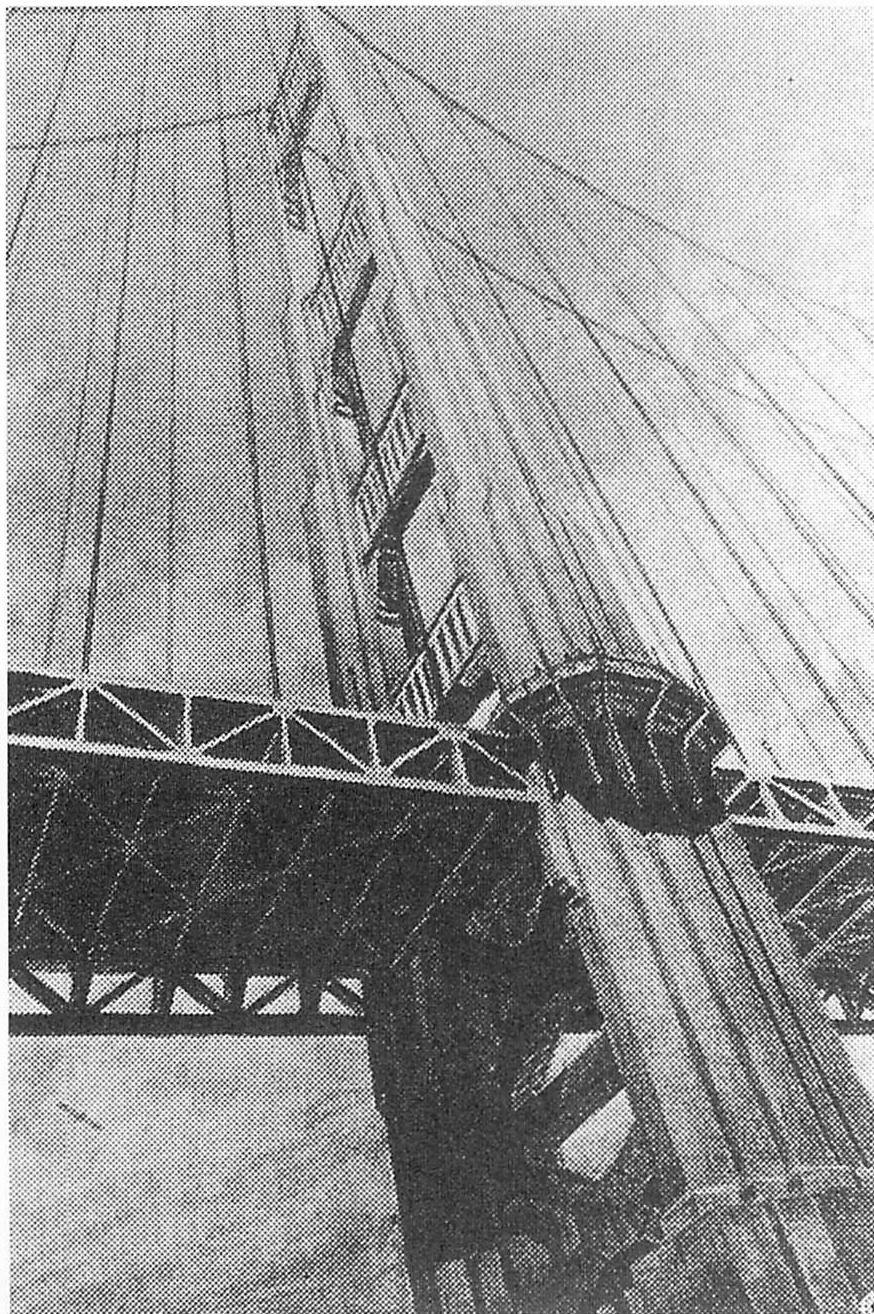

In the 20th century, we have had the illusion that all the order we see around us in the world can be explained by science — mainly, we assume, by physics. But physics and the other sciences tend to represent certain things for us as mechanisms. This gives us a partial picture of some kinds of order. That is all. We may take, for instance, the structure of a leaf, the structure of a bridge, the structure of an atomic nucleus. In each of these cases we have a well-worked-out conception of the mechanical order which is there. The stems of the leaf support its membranes, which hold the cells, which receive sunlight, and transform the energy of the sunlight into materials from which the leaf can grow. The members of the bridge are conceived as elements in a certain pattern of forces which develops inside the bridge in response to a given pattern of loads, trucks and cars passing over it, wind forces, stresses and strains caused by thermal expansion, and so on. Even in the picture we have of the atomic nucleus, the order is conceived essentially in relation to forces. The particles of which the atom is made are themselves seen as carriers of forces which hold the nucleus together and which, under particular conditions, may also cause it to fly apart.

What is the order which physics helps us talk about in each of these cases? It is only the mechanical order. The order is always described—and even invented—in relation to the way the thing works as a mechanism. Within our current scientific world-picture, each of the three examples I have given is conceived of as a little machine that produces certain kinds of results when pushed, prodded, squeezed, or bombarded. So, in the present scientific world-picture, the order which we see in the thing, the way we describe it to ourselves, is essentially the order of a machine which has a certain mechanical mode of operation—or which, at any rate, has a certain kind of mechanical behavior as a result of the arrangement of its parts.

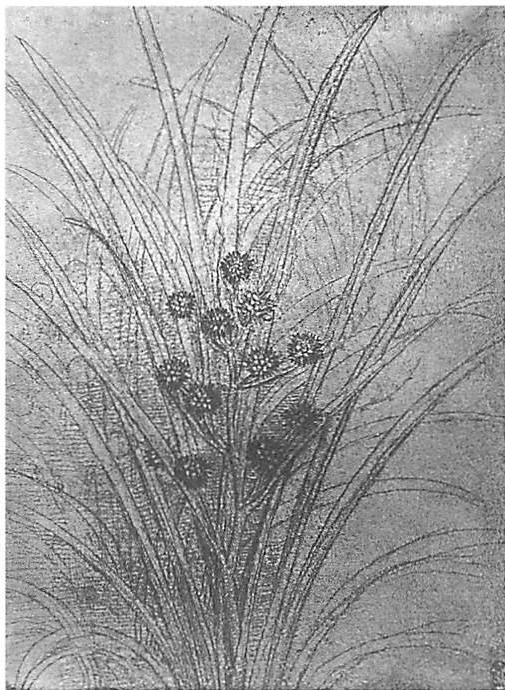

But what of the order itself? The order itself—that order which exists in a leaf, in the Ise shrine, in the yellow tower, or in a Mozart symphony, or in a beautiful tea bowl—a harmonious coherence which fills us and touches us—this order cannot be represented as a mechanism. Yet it is this harmony, this aspect of order, which impresses us and moves us when we see it in the world.

It is almost impossible to view a Mozart symphony as a machine which has certain kinds of behavior. The same is true of the yellow tower. If, as an artist, I want to understand the tower—if I want to make something of comparable beauty—it is useless to conceive it as a mechanism, because the beauty and order which I see in it, and yearn for, cannot be expressed in any way that can be understood mechanically. So, in works of art, the mechanistic view of order always makes us miss the essential thing. Although 20th-century science gives us a way of seeing order as a producer of effects—in particular because the scientific view of things shows us the geometry of matter as if it were part of a machine, a machine which can do certain things—we still do not have a way of seeing the order of a thing which simply exists. We do not have a way of seeing the order in the smile of a statue of the Buddha, or in the exact position of a flower in a vase, or of the arrangement of notes in a song, or of the harmony within a wonderful building.[15]

5 / DESCARTES

The mechanistic idea of order can be traced to Descartes, around 1640. His idea was: if you want to know how something works, you can find out by pretending that it is a machine. You completely isolate the thing you are interested in — the rolling of a ball, the falling of an apple, the flowing of the blood in the human body — from everything else, and you invent a mechanical model, a mental toy, which obeys certain rules, and which will then replicate the behavior of the thing. It was because of this kind of Cartesian thought that one was able to find out how things work in the modern sense.¹⁶

However, the crucial thing which Descartes understood very well, but which we most often forget, is that this process is only a method. This business of isolating things, breaking them into fragments, and of making machinelike pictures (or models) of how things work, is not how reality actually is. It is a convenient mental exercise, something we do to reality, in order to understand it.

Descartes himself clearly understood his procedure as a mental trick. He was a religious person who would have been horrified to find out that people in the 20th century began to think that reality itself is actually like this. But in the years since Descartes lived, as his idea gathered momentum, and people found out that you really could find out how the bloodstream works, or how the stars are born, by seeing them as machines — and after people had used the idea to find out almost everything mechanical about the world from the 17th to the 20th centuries — then, sometime in the 20th century, people shifted into a new mental state that began treating reality as if this mechanical picture really were the nature of things, as if everything really were a machine.

For the purpose of discussion, in what follows, I shall refer to this as the 20th-century mechanistic viewpoint. The appearance of this 20th-century mechanistic view had two tremendous consequences, both devastating for artists. The first was that the “I” went out of our world-picture. The picture of the world as a machine doesn’t have an “I” in it. The “I,” what it means to be a person, the inner experience of being a person, just isn’t part of this picture. Of course, it is still there in our experience. But it isn’t part of the picture we have of how things are. So what happens? How can you make something which has no “I” in it, when the whole process of making anything comes from the “I”? The process of trying to be an artist in a world which has no sensible notion of “I” and no natural way that the personal inner life can be part of our picture of things — leaves the art of building in a vacuum. You just cannot make sense of it.

The second devastating thing that happened with the onset of the 20th-century mechanistic world-picture was that clear understanding about value went out of the world. The picture of the world we have from physics, because it is built only out of mental machines, no longer has any definite feeling of value in it: value has become sidelined as a matter of opinion, not intrinsic to the nature of the world at all.

And with these two developments, the idea of order fell apart. The mechanistic idea tells us very little about the deep order we feel intuitively to be in the world. Yet it is just this deep order which is our main concern.

The real nature of this deep order hinges on a simple and fundamental question: “What kinds of statements do we recognize as being true or false?” This is the question which divides the mechanistic world-view originating with Descartes from the one which I describe in this book.

In the world-view initiated by Descartes — and largely accepted by scientists in the 20th century — it is believed that the only statements

which can be true or false are statements about mechanisms. These are the so-called "facts" familiar to everyone in the 20th century.

In the world-view I am presenting, a second kind of statement is also considered capable of being true or false. These are statements about relative degree of life, degree of harmony, or degree of wholeness — in short, statements about value. In the view I hold, these statements about relative wholeness are also factual, and are the essential statements. They play a more fundamental role than statements about mechanisms. It is for this reason that the view of order which I am presenting in this book inevitably involves us in a shift of world-view.

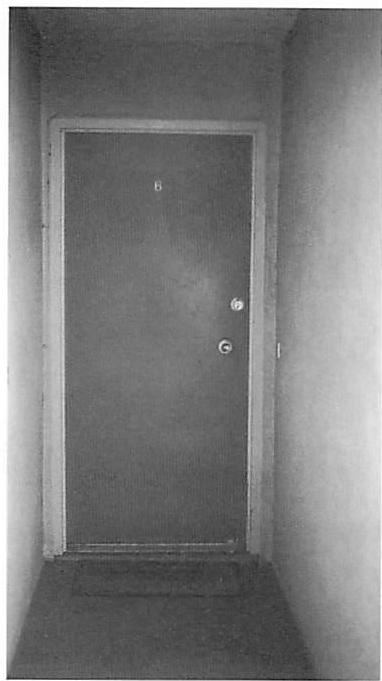

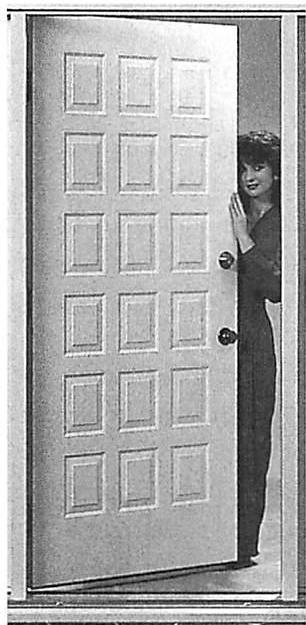

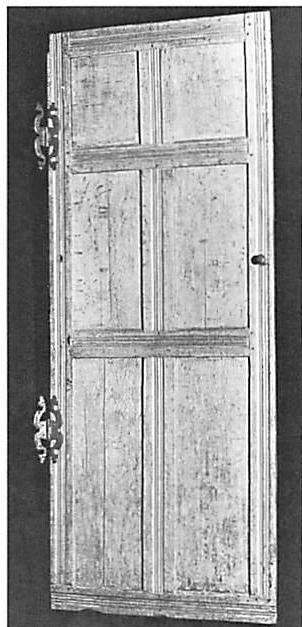

Suppose I am trying to place a door in a certain wall. While I try to decide where to put it, I can make various mechanical statements of fact. For example, I can say of one door that it is wide enough to allow a refrigerator through it, that it will resist a standard fire for one hour, that it weighs 25 kilograms, and so on. I can also make more elaborate statements of fact. In one case people can see through the door, in another they can't. I can even say that the position of one door may disrupt people's work because their desks are too exposed to the noise of passers-by. I might have to do an experiment to check this statement, but it is still, in principle, a statement of fact in the normal Cartesian sense. All these statements are, potentially, statements of fact in the 20th-century mode. This is the sense in which the word "fact" is understood today. It is generally agreed that statements of this type may be true or false.

But if I am trying to put the door in the wall, there is also a second kind of statement about the different possible positions for the door. For example: "When the door is in a certain range of positions, the result is more harmonious than other positions." "This position for the door is more in keeping with the wholeness of the room than this other position." "One door frame is more harmonious and more in keeping with the life of the room than another door frame." "One door creates more life in the room

than another door." "A pale yellow on this door has more life than a dark gray." Within the canon of 20th-century science, these are not considered statements which can be true or false. They are thought of as statements of opinion. As a matter of principle within the 20th-century mechanistic view, statements of this kind may not be considered potentially true or false.

We have learned to live with this principle simply because we are used to it. But consider how bizarre it really is. As architects, builders, and artists, we are called upon constantly—every moment of the working day—to make judgments about relative harmony. We are constantly trying to make decisions about what is better and what is worse in an evolving building. If the only statements considered potentially true or false are mechanistic statements of fact, and if all statements of harmony, beauty, what is better or worse, what has more life or less life, are always considered matters of opinion which can only be referred to private and arbitrary canons of judgment—then, in principle, rational discussion about buildings should be impossible.

The devastating impact of this state of affairs on the progress of architecture has not, I think, been sufficiently discussed in recent decades. Within a world-view in which statements about value are not allowed, by the accepted canon, to be considered as potentially true or false, we cannot (in theory) legitimately discuss what we are doing as architects with any hope of reaching consensus. If we accept the 20th-century idea that statements of value are — of necessity — merely statements of opinion, it is in principle impossible to reach any sensible shared conclusion in the process of making the environment — only arbitrary and private conclusions. The chaos with which we are familiar in the built world, must then follow as an inevitable conclusion — as indeed it has.

Discussion of an earlier book may perhaps help to make the problem clear. In 1977 my colleagues and I published a book called A PATTERN LANGUAGE.[17] In this book we made a number of observations about good environments. The

book was—and still is—extremely controversial. It describes a number of key patterns in cities, buildings, gardens, and building details which are necessary to support life. Some people said that it described an important form of truth. Others said it was impossible for the book to describe any form of truth and that it was only opinion dressed up as truth.

According to the strict canon of contemporary science, it would indeed be impossible for statements about "good" patterns to be true since they do not have the right logical form to be true. In the present-day scientific canon patterns in the pattern language must be statements of opinion. And some writers, working within the Cartesian-mechanistic mental framework, indeed took this point of view.[18]

However, after the book was published, many hundreds of other people came to the conclusion that the statements in the pattern language are not statements of opinion but are in some sense true. Since the patterns seem to confirm people's instincts about what is true in the environment, to these people, who were not

committed to the mechanistic canon, the patterns represented a triumph of deeper wisdom reflecting common sense.[19]

What are we to make of this? It suggests, I think, that there must be some other way not covered by the limited mechanistic idea of what can and cannot be true, in which statements about value can be true. And indeed, this is the main philosophical assumption which underlies the arguments of the present book.

Throughout this book I shall present a further and more extended idea of objective truth—one which extends the current idea of truth given us by 19th- and 20th-century science in such a way that it includes statements of value. As I hope to show, this new extended idea of truth is not only objective, but is also directly linked to people's feelings. Most importantly, this extended idea of objective truth will allow statements about relative harmony, wholeness, and so forth to be judged as true or not true. In this view, these kinds of statements are not left as private intuitive opinions or agendas, but describe the structure of things in the world as they are.

6 / THE DESTRUCTIVE IMPACT OF MECHANISTIC THOUGHT ON THE ART OF BUILDING

It is not a small thing to construct a theory of architecture based on a new form of truth. To make sure the reader understands—thoroughly—why I believe it is necessary for us to develop a new form of truth, I shall give a few more examples of the highly negative impact the mechanistic idea of truth has had on the art and architecture of the 20th century.

In the architecture of the last decades, constructive discussion about value has become difficult—sometimes nearly impossible. In the wake of the mechanistic world-picture, we have constructed a pluralist view of value. When we want to discuss the pros and cons of a particular action—in architecture, planning, landscape—

each person is understood to have a "view," or attitude, or value-orientation. There is rarely any theoretically coherent way of combining different people's values. So, if it is a public matter, we simply give each person the opportunity to express his point of view as strongly as possible, in the hope that the ensuing democratic dialogue will somehow get us to a balance point roughly in the middle.

And this is indeed what happens in 20th-century discussion of building projects, planning, and the actions which may arise in any public situation. In discussing what to do in a particular part of a town, one person thinks poverty is the most important thing. Another person thinks ecology is the most important thing. An-

other person takes traffic as his point of departure. Another person views the maximization of profit from development as the guiding factor. All these points of view are understood to be individual, legitimate, and inherently in conflict. It is assumed that there is no unitary view through which these many realities can be combined. They simply get slugged out in the marketplace, or in the public forum.

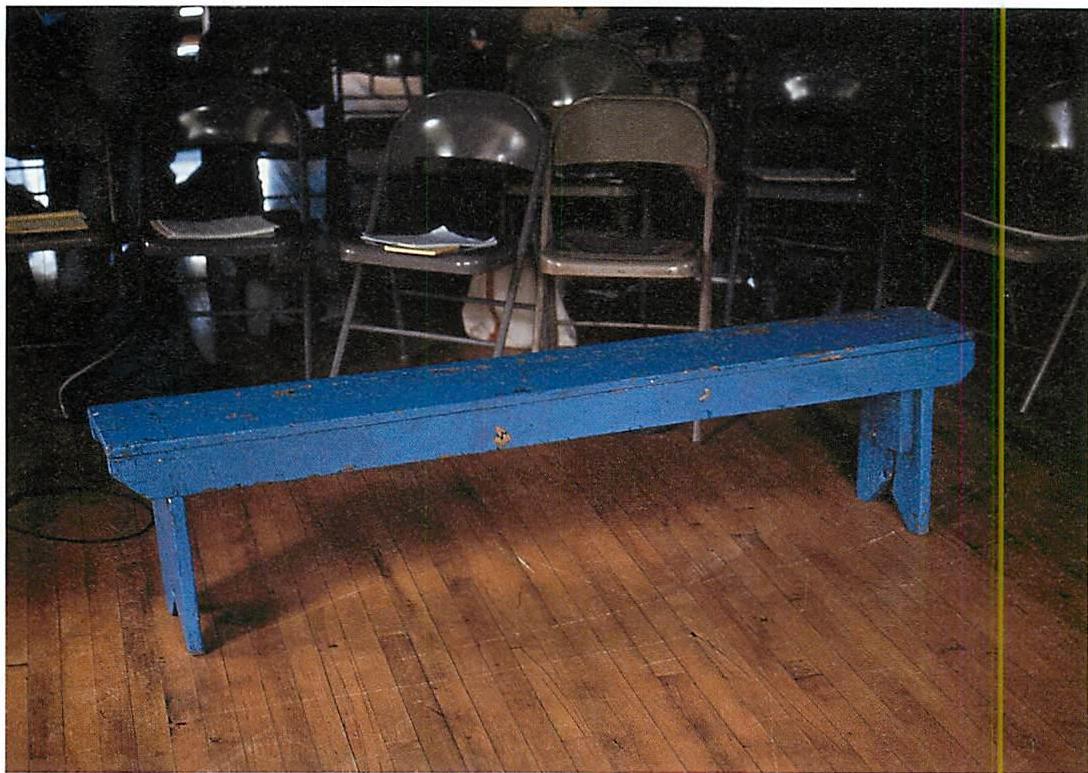

But instead of lucid insight, instead of growing communal awareness of what should be done in a building, or in a park, even on a tiny park bench—in short, of what is good—the situation remains one in which several dissimilar and incompatible points of view are at war in some poorly understood balancing act.

Our zoth-century failure to construct a living world arises necessarily from this situation. Since, in the mechanistic framework, the different values brought to architecture are inherently inconsistent, architects quite contentedly take the confusion of their many individual, wildly different, and inconsistent ways of thinking as the basic situation which must exist in architecture. Consciously or unconsciously, the architect assumes that only "factual" statements (in the mechanistic sense) can be true, and therefore has it as a further (unconscious) assumption

that the idea of what is good is something that you add to the factual statements—something that is (of necessity in the current scientific world-view) only a matter of opinion.

All this sounds abstract. But its impact on our world has been enormous. It has created a mental climate of arbitrariness, and has laid the foundation for an architecture of absurdity.

For example, a few years ago a man came to show me a design he had drawn for a building. The building was to be made entirely of oil-drums filled with water. It was intended to be an energy-efficient building. Yet the building was absurd in many ways. It was ugly, impractical, hard to build, not even pleasant to be near. But it made sense to him because, as far as he was concerned, he was only trying to make an energy-efficient building. He had chosen this particular goal, and elevated it above all others, making it the basis for his work.

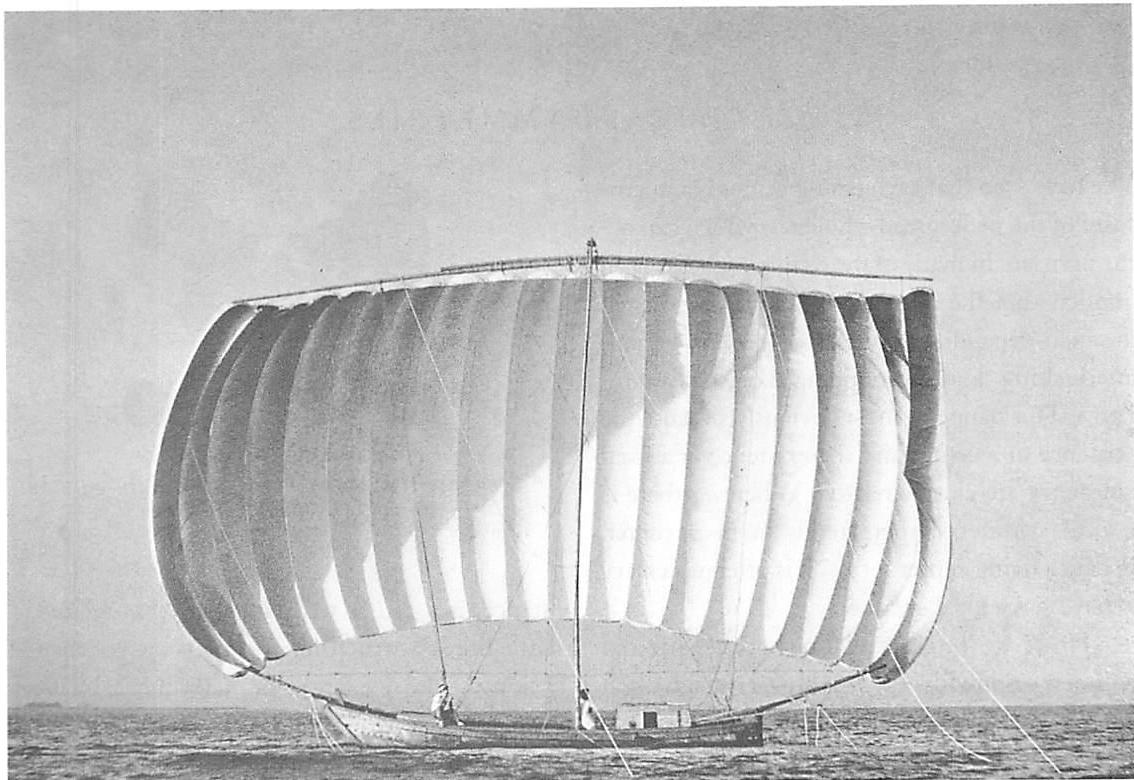

To Buckminster Fuller, weight was paramount. He therefore emphasized the idea of least-weight structures. It didn't matter to him that a geodesic dome is difficult to use, perhaps not so pleasant to look at, almost impossible to subdivide internally in a nice way. What mattered was his chosen goal of making buildings which span the longest distance for the least possible weight.[20]

Le Corbusier chose the separation of functions. With the CIAM (Congrès International de l'Architecture Moderne), he decided that housing, recreation, transportation, and work were of such importance that he chose as an underpinning value the task of giving these four functions adequate and separate space in the city. In the process, he may have had to forget

about the interweaving of other functions—but it was this goal of separating the four functions, above all others, which dominated his city plans. This was his chosen value, and this is what he reflected in his diagram of the Radiant City.[21]

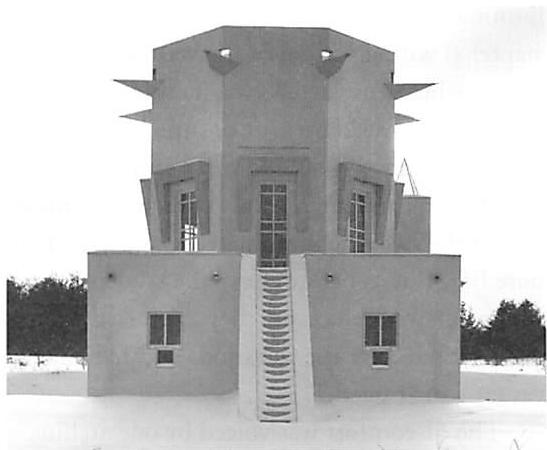

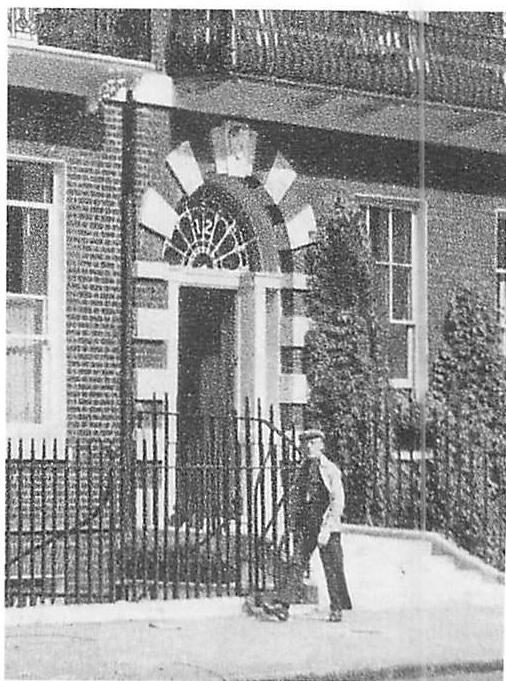

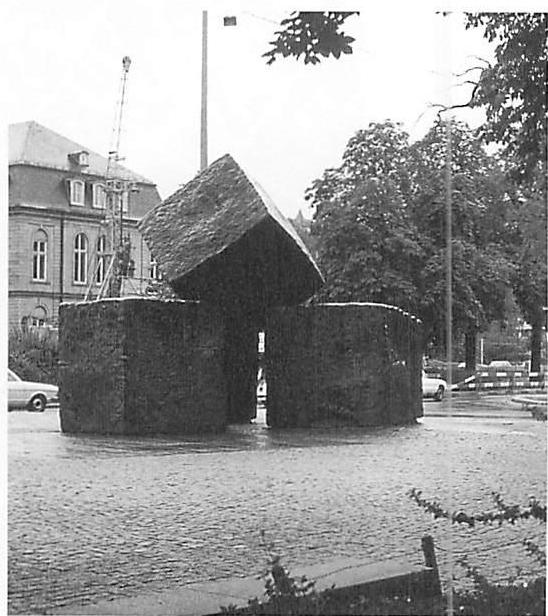

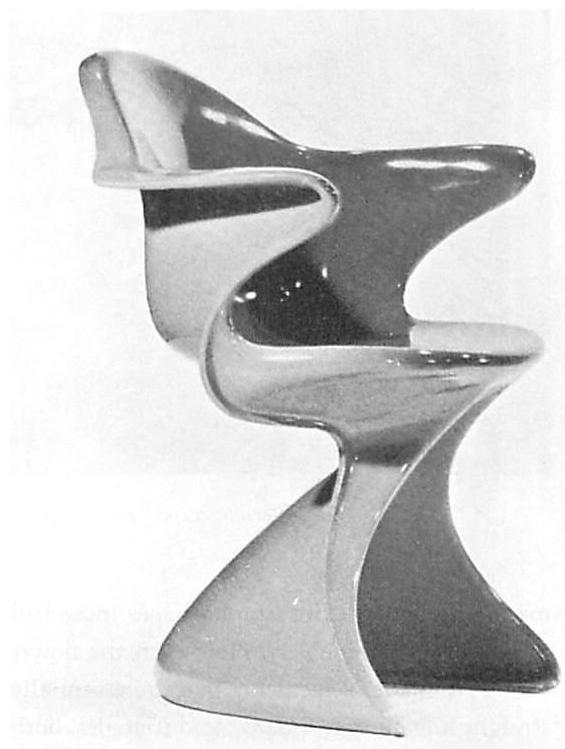

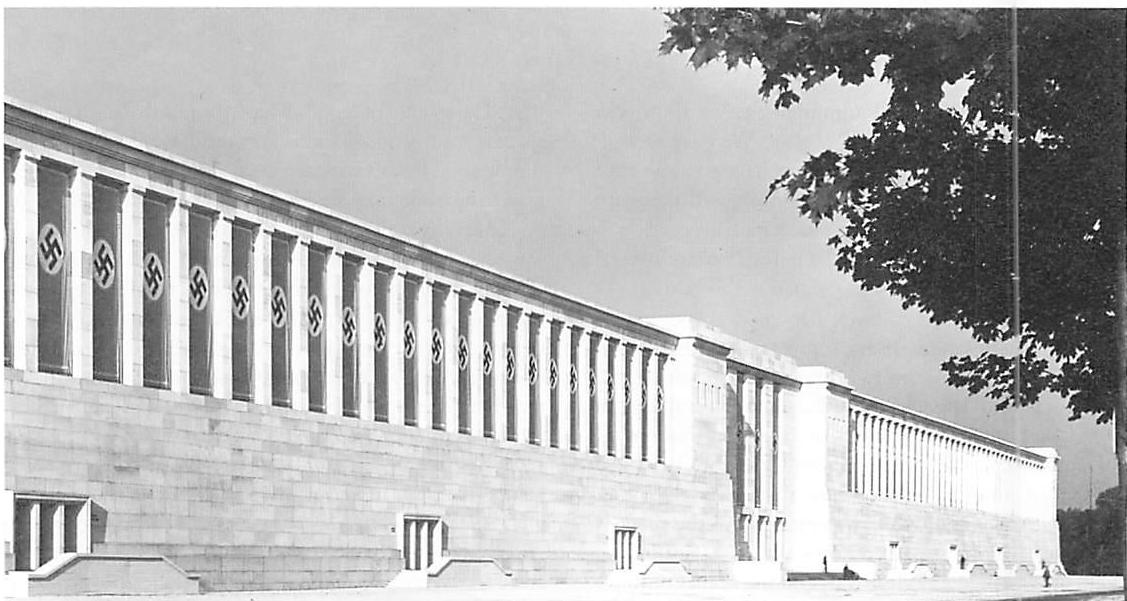

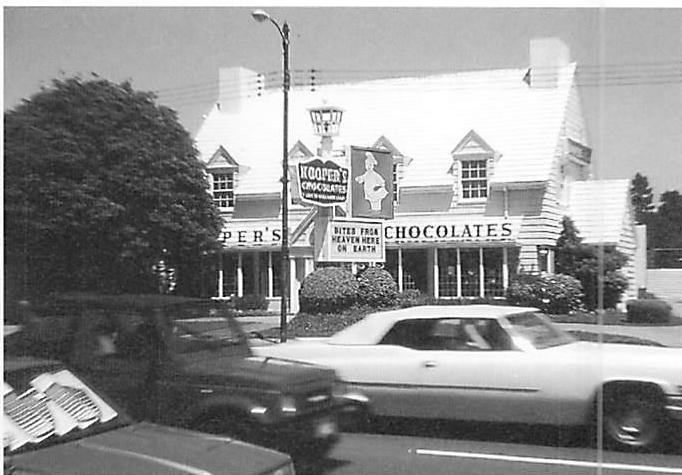

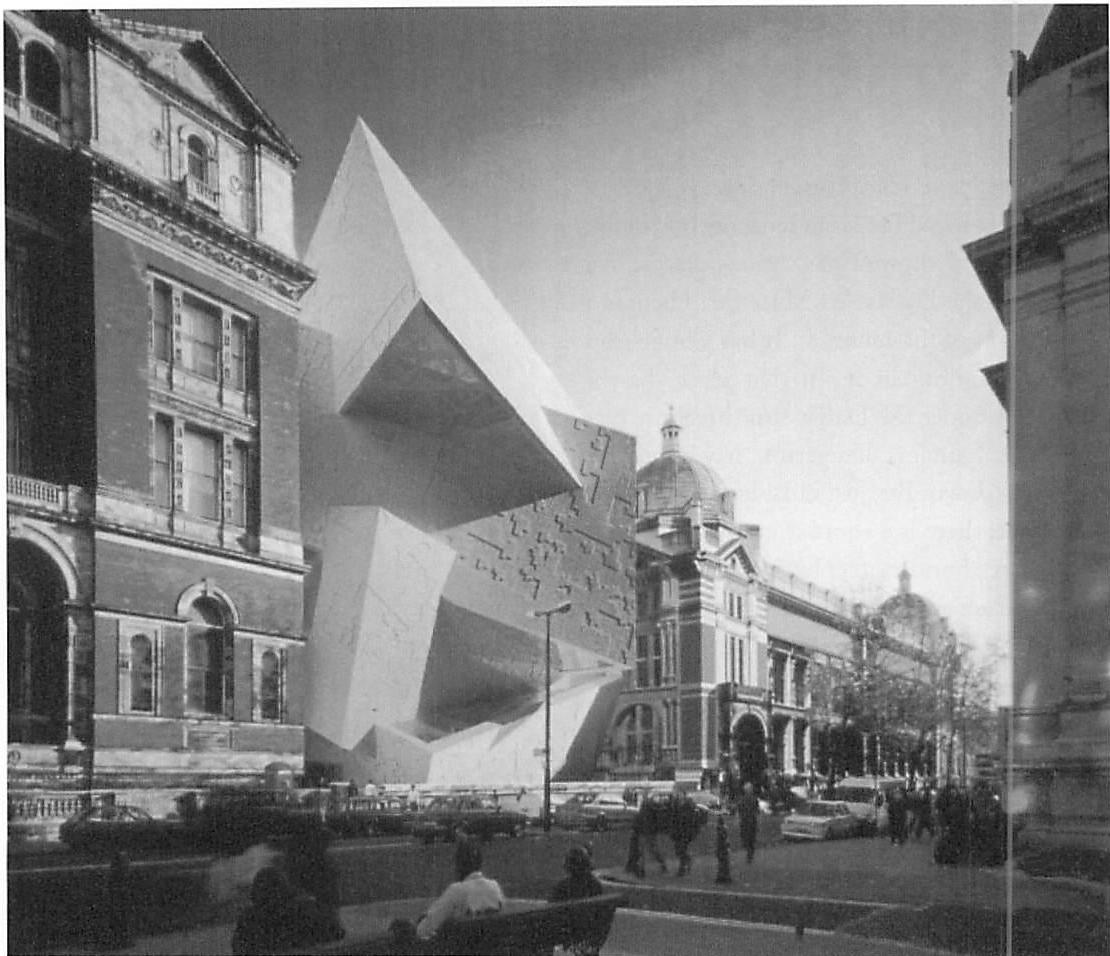

More recently we have examples of architects who choose historical reference as the primary value in their work. Look, for instance, at the neo-classical facade on this page. In this case it might not matter whether the building works well or not: what matters is that it has a certain "image"—perhaps the image of Palladio mixed with images of the 1940s. This architect chose this particular goal—the making of an image—above all others.

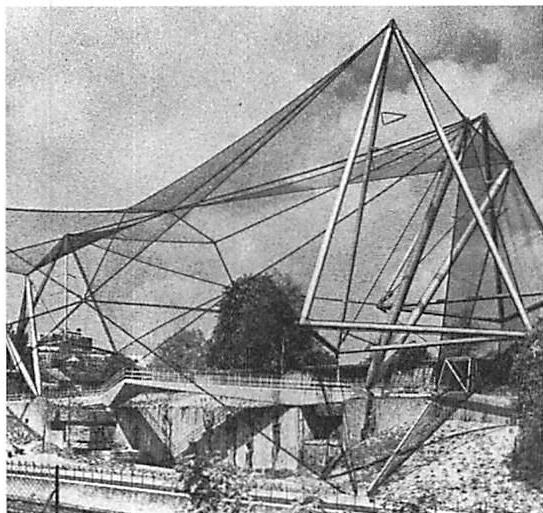

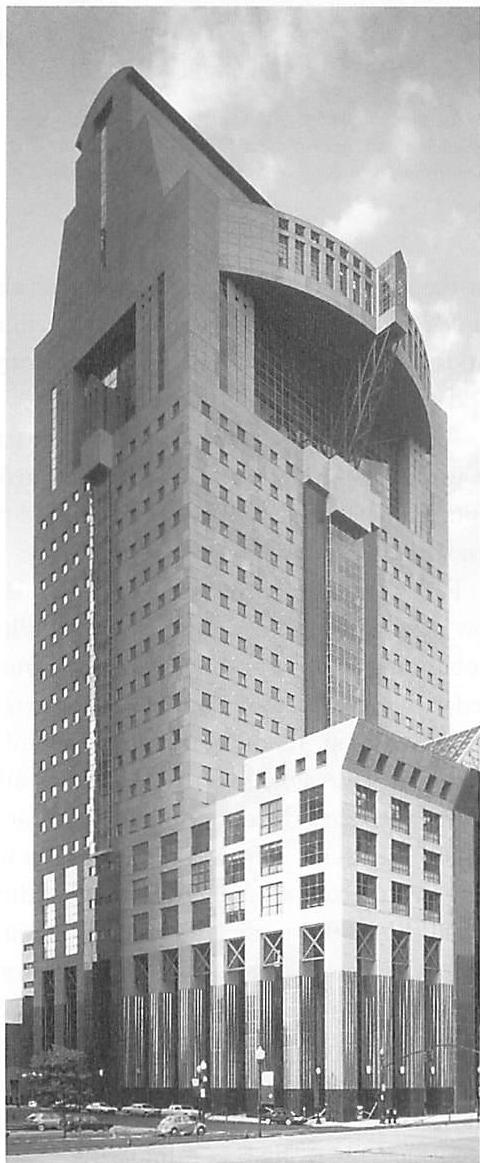

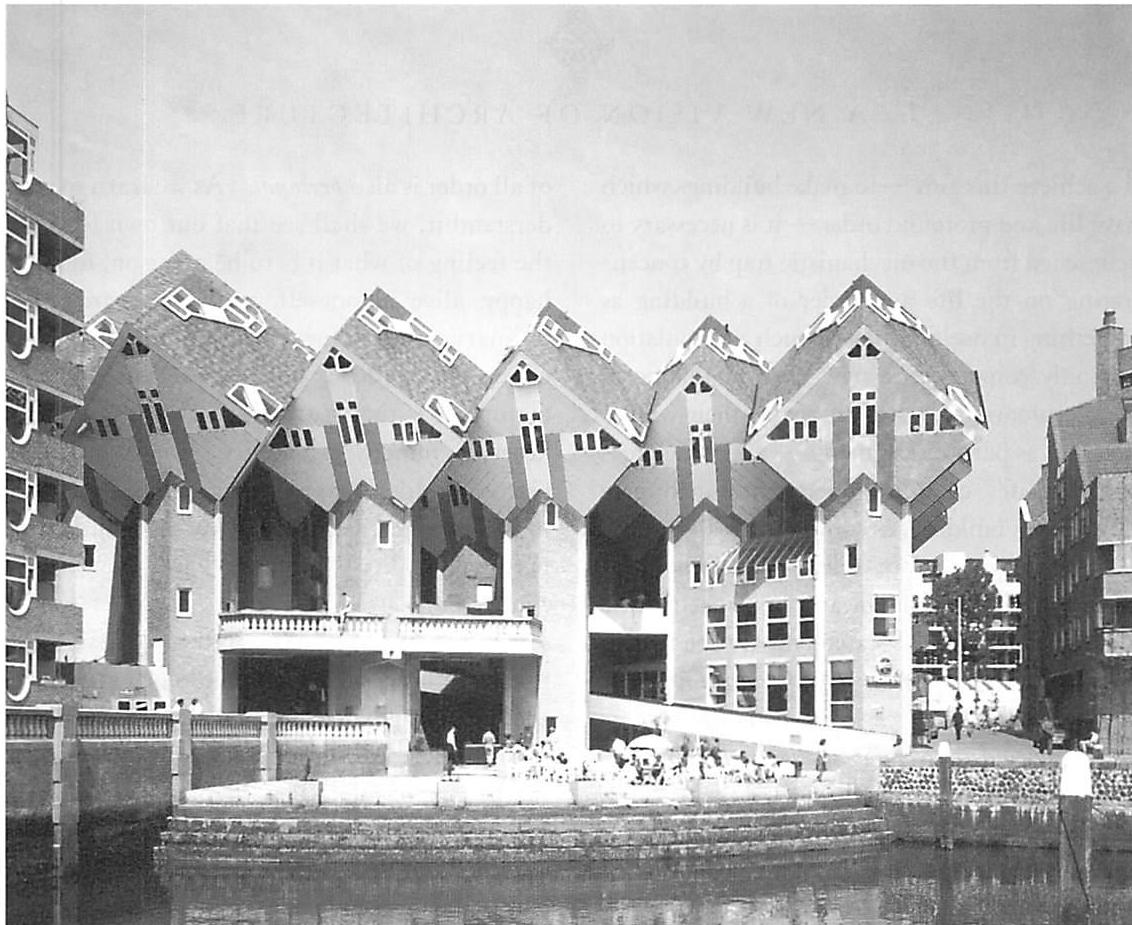

Another architect may choose to make wildly formal geometric shapes on the grounds that they are "good design." There is no empirical basis for believing that this is true. But again, in the absence of believable empirical facts about what is true or not, one must choose something. So, a one-sided belief that crystalline geometric forms have an absolute goodness can provide yet another architect with the underpinning for his work: as in the Rotterdam offices contained in rhombic crystals which I show on the facing page.

Architects make different idiosyncratic choices because within the mechanistic worldview it is not possible to function mentally without making some private choices of this kind. Virtually every architect who works today is forced to do something similar. Yet another architect is an adherent of ecology. He seeks to preserve nature. But how should this be done? In fire-prone brushland above the Berkeley hills, should the land be cleared of trees and brush to protect it against fire? Should it be made into a useful park, thus leaving the trees for shade? Should it be left messy and wild to preserve the habitat of the native birds and plants (a biologist's point of view)? Should it be left as it is simply to save money (the university's point of view)? Should it be wild, or tamed? Once again, within the mechanistic framework, it is simply a matter of

opinion. You take your pick between the opposing viewpoints. Although these points of view do not have quite the insane arbitrariness of the more extreme architectural examples I have given, still each point of view that can be expressed is still essentially arbitrary: whether one of them is chosen, or some combination of them, any particular choice is individual, and arbitrary again.

So far the 20th-century response to the arbitrariness inherent in mechanistic thought has been to keep on asserting the dignity and privacy of value. Something like this: "Science only tells us about facts. When it comes to figuring out what one ought to do, that is a private matter of art or ethics. It is your natural right to work out your own values. Not only will our scientific world-view not tell you anything about value,

it is your democratic obligation to do it for yourself."

But all this only continues to make the "life" of towns and buildings and landscapes seem unreal, almost as if it did not exist. It also makes cooperative work, collaboration, and social agreement very difficult in principle. It has a superficial permissiveness which seems to encourage different opinions. But what is encouraged, really, is only the essential arbitrariness of ideas rooted in a mechanical view of how the world is made.

What we need is a sharable point of view, in which the many factors influencing the environment can coexist coherently, so that we can work together—not by confrontation and argument—but because we share a single holistic view of the unitary goal of life.

7 / A NEW VISION OF ARCHITECTURE

To achieve this aim — to make buildings which have life and profound order — it is necessary to be rescued from the mechanistic trap by concentrating on the life and order of a building as something in itself.²² I believe such a formulation can only come from a new view of the world which intentionally sees things in their wholeness, not as parts or fragments — and which recognizes “life,” even in an apparently inanimate thing like a building, as something real.

In this new view of order we shall find, necessarily, a post-Cartesian and non-mechanistic idea of what kinds of statements can be true, a theory in which statements about relative degree of harmony, or life, or wholeness — basic aspects of order — are understood as potentially true or false. This means we shall have a view of the world in which the relative degree of life of different wholes is a commonplace and crucial way of talking about things.

Such a new view of order will create a new relationship between ideas of ornament and function. In present views of architectural order, function is something we can understand intellectually; it can be analyzed through the Cartesian mechanistic canon. Ornament, on the other hand, is something we may like, but cannot understand intellectually. One is serious, the other frivolous. Ornament and function are therefore cut off from each other. There is no conception of order which lets us see buildings as both functional and ornamental at the same time.

The view of order which I describe in this book is very different. It is even-handed with regard to ornament and function. Order is profoundly functional and profoundly ornamental. There is no difference between ornamental order and functional order. We learn to see that while they seem different, they are really only different aspects of a single kind of order.

What is even more important, we shall see that the structure I identify as the foundation

of all order is also personal.²³ As we learn to understand it, we shall see that our own feeling, the feeling of what it is to be a person, rooted, happy, alive in oneself, straightforward, and ordinary, is itself inextricably connected with order. Thus order is not remote from our humanity. It is that stuff which goes to the very heart of human experience. We resolve the Cartesian dilemma, and make a view of order in which objective reality “out there” and our personal reality “in here” are thoroughly connected.

In forming this idea of order, we shall have to take intellectual steps which touch all of science — even physics and biology — because we need to include a new view of what statements can be true or false. The life of a building will become visible as something empirically real. We shall see that the yellow tower and other buildings in the first group of examples in this chapter empirically have more life than the modernistic buildings in the second group of examples. This will become objectively clear not as a matter of opinion, but as a matter of fact about the order they contain.

The theory which I shall lay out is in no sense against science; it is simply an extension of science. Like all science, it will show a view of things which depends on clearly defined structures: but structures which show us order in new ways, not available to present-day scientific thought. What will be presented is a slightly modified vision of science, which includes mechanism as understood in the past, but also includes a powerful new kind of structure, coupled with a new form of observation, that transforms the range and extent of the experiences which science can illuminate.

The new view will show us the world as an altogether different kind of place from the one we have imagined. When we are done, everything will look different, not only buildings.

Flowers, puddles, waterfalls, bridges, mountains, the moon, the earth, the tides, the waves of the ocean, paintings, the rooms in which we live, the clothes we wear—all of these will be different in our eyes and will appear to us as something fresh and marvelous. We shall, then, literally, be living in a different mental universe.

At that stage we shall not only have a concrete grasp of order as a single phenomenon which affects all of architecture, but shall also be led to a view of space and substance which is transcendental. Although this conception of order is lucid in material terms, it will also provide us with a partial understanding of the nature of

matter which reaches beyond our present material view of substance, and beckons to some domain beyond the limits of space and time.

Thus it is not only the detail of what "order" is which needs to be questioned, but also the very nature of order.[24] So long as we have a confused or inaccurate conception of what kind of thing order is, we shall inevitably make buildings which are ugly, houses which do not support ordinary human well-being, gardens and streets which are at odds with nature, and a world which destroys our souls.

To make good architecture, we must fundamentally alter our idea about the nature of order — about the kind of thing it is.

NOTES

- Negative entropy measures the unlikelihood of a configuration of particles. It can account for low-level order in aggregates of molecules, but not for any complex order which is interesting in art or architecture — nor indeed can it deal with complex order in physics or biology.

- Including Fred Attneave, APPLICATIONS OF INFORMATION THEORY TO PSYCHOLOGY: A SUMMARY OF

BASIC CONCEPTS, METHODS, AND RESULTS (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1959); W. R. Garner, UNCERTAINTY AND STRUCTURE AS PSYCHOLOGICAL CONCEPTS (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1962); and others. 3. For example Purcell, "Order and Magnetism," in PARTS AND WHOLES, Daniel Lerner, ed. (New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963).

Indeed, the feeble nature of this first attempt, and its comparative uselessness for art, was carefully analyzed by Rudolph Arnheim, ENTROPY AND ART (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971).

The successful analysis of the crystal groups was vital, but extremely limited in its scope. Andreas Speiser, THEORY OF GROUPS OF FINITE ORDER (Berlin: J. Springer, 1937).

See, for example, Albert G. Wilson and Donna Wilson, eds., HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURES (New York: American Elsevier Publishing Company, Inc., 1969).

H. Eugene Stanley, "Fractals and Multifractals: The Interplay of Physics and Geometry," in Armin Bunde and Shlomo Havlin, eds., FRACTALS AND DISORDERED SYSTEMS (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1991).

Structural grammars of the kind first defined by Chomsky are special cases of this kind of order. For instance, Noam Chomsky, STRUCTURAL LINGUISTICS (The Hague: Mouton, 1959).

Turing's early theory of morphogenesis might be looked at like this. A. M. Turing, "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis," in PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY, B (London, 1952), pp. 237 ff.

For example, André Lwoff, BIOLOGICAL ORDER (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1965); C. S. Waddington, THE STRATEGY OF THE GENES: A DISCUSSION OF SOME ASPECTS OF THEORETICAL BIOLOGY (London: Allen and Unwin, 1957).

L. L. Whyte, THE UNITARY PRINCIPLE IN PHYSICS AND BIOLOGY (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1949) and L. L. Whyte, ACCENT ON FORM (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954).

René Thom, STABILITÉ STRUCTURELLE ET MORPHOGÉNÈSE (Paris: Christian Bourgeois, 1972) and James Gleick, CHAOS: MAKING A NEW SCIENCE (New York: Viking, 1987).

David Bohm, "Remarks on the Notion of Order," and "Further Remarks on the Notion of Order," in C. H. Waddington, ed., TOWARDS A THEORETICAL BIOLOGY: 2. SKETCHES (Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1976).

An account of artistic order was tried by Ernst Gombrich in ORDER AND ART (London: Allen and Unwin, 1977), but in this book order still appears as something additional, pasted on top of whatever else art produces. The concepts are still only barely useful for an artist.

The progressive mechanization of our modern world-picture was exhaustively described by E. J. Dijksterhuis, THE MECHANIZATION OF THE WORLD PICTURE (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1959; translated and reprinted, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986). It is also the main theme of Alexandre Koyré's FROM THE CLOSED WORLD TO THE INFINITE UNIVERSE (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1957) which ends with these words: "The infinite Universe of the New Cosmology, infinite in Duration as well as Extension, in which eternal matter in accordance with eternal and necessary laws moves endlessly and aimlessly in eternal space, inherited all the ontological attributes of Divinity. Yet only those — all the others the departed God took away with Him."

The essence of mechanistic theory is that the machine is governed only by local effects: by actions which are, strictly speaking, pushing and pulling. There is no "action at a distance," and above all, the whole has no way of influencing the parts. In 17th-century physics (Newton) there was some action at a distance: gravity. In 19th- and early 20th-century physics there was some action at a distance, in the field effects of electricity, light, and so on. The late 20th century has been marked by an exorcism of action at a distance, and by now electromagnetic fields, quantum theory, even the working of Hamilton's function and the principle of least action are all described as far as possible in terms of local effects. See for instance Richard Feynman, QED (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985).

Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein, Ingrid King, Shlomo Angel, and Max Jacobson, A PATTERN LANGUAGE (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

For example, Jean Pierre Protzen, "The Poverty of the Pattern Language," CONCRETE: JOURNAL OF THE STUDENTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE, Part one: vol. 1, no. 6, November 1, 1977; Part two: vol. 1, no. 8, November 15, 1977, University of California, Berkeley; reprinted in DESIGN STUDIES, vol. 1, no. 5 (London, July 1980), pp. 291-98.

Reviewers expressing this point of view published their comments in many dozens of articles written since 1975. A strong example by Stewart Brand appeared in THE WHOLE EARTH CATALOG (Sausalito, Calif.: Doubleday, 1980-90).

Buckminster Fuller, "The Long Distance Trending in Pre-Assembly," IDEAS AND INTEGRITIES: A SPONTANEOUS AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL DISCLOSURE, ed. R. W. Marks (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963).

Le Corbusier, THE RADIANT CITY, Pamela Knight and Eleanor Levieux, trans. (New York: Orion Press, 1967).

The idea that order may exist as a fundamental, not machine-like, idea has become visible in some parts of 20th-century physics. One of the first examples was Pauli's exclusion principle (Wolfgang Pauli, "Exclusion Principle and Quantum Mechanics," COLLECTED SCIENTIFIC PAPERS, vol. 2, R. Kronig and V. F. Weisskopf, eds. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1964): a pure property of arrangement was shown to govern the behavior and position of electrons, without being caused by the action of a force or mechanism, but purely as a result of pattern and order in themselves.

See chapters 8-11 of this book, and Book 4, throughout.

The possibility that the order observed in science and the order created in art might ultimately be treated as one phenomenon has been mentioned by many writers, starting with Goethe. In recent writings, see for example, György Kepes, THE NEW LANDSCAPE IN ART AND SCIENCE (Chicago: Theobald, 1956); Hermann Hesse, DAS GLASPERLENSPIEL (Zürich, 1943); Christopher Alexander, "The Bead Game Conjecture," in ORDER AND ART, György Kepes, ed., (New York: Braziller, 1967).

What is living structure?

What is life in buildings?

What is a living world?

What is the structure of a living world?

CHAPTER ONE: THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

1 / INTRODUCTION

It is widely agreed today that we want to build towns and buildings which play their proper role in the preservation and continuation of life on earth. This has come about, in large part, as a result of the growing interest in ecology. When we study ecology, we begin with the idea that we must preserve nature, preserve the rain forest and chaparral, preserve the animals and plants of the earth. This general desire to preserve living things is then extended to tell us that we should build buildings and towns and neighborhoods, in such a way that their action also plays its role in the balanced harmony and life of the earth.

At first the effort to make buildings play their proper part in the living system of nature was seen as a narrow problem, which meant that one's use of energy, use of materials, use of resources, should all be consistent with the preservation of the earth as a balanced living system. More recently this interest has expanded. Many people now define their aim to be the creation of towns and buildings which are part of the living fabric of the earth and which are themselves, in short, alive.¹