The four books of The Nature of Order constitute the ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth in a series of books which describe an entirely new attitude to architecture and building. The books are intended to provide a complete working alternative to our present ideas about architecture, building, and planning — an alternative which will, we hope, gradually replace current ideas and practices.

| Volume 1 | THE TIMELESS WAY OF BUILDING |

|---|---|

| Volume 2 | A PATTERN LANGUAGE |

| Volume 3 | THE OREGON EXPERIMENT |

| Volume 4 | THE LINZ CAFE |

| Volume 5 | THE PRODUCTION OF HOUSES |

| Volume 6 | A NEW THEORY OF URBAN DESIGN |

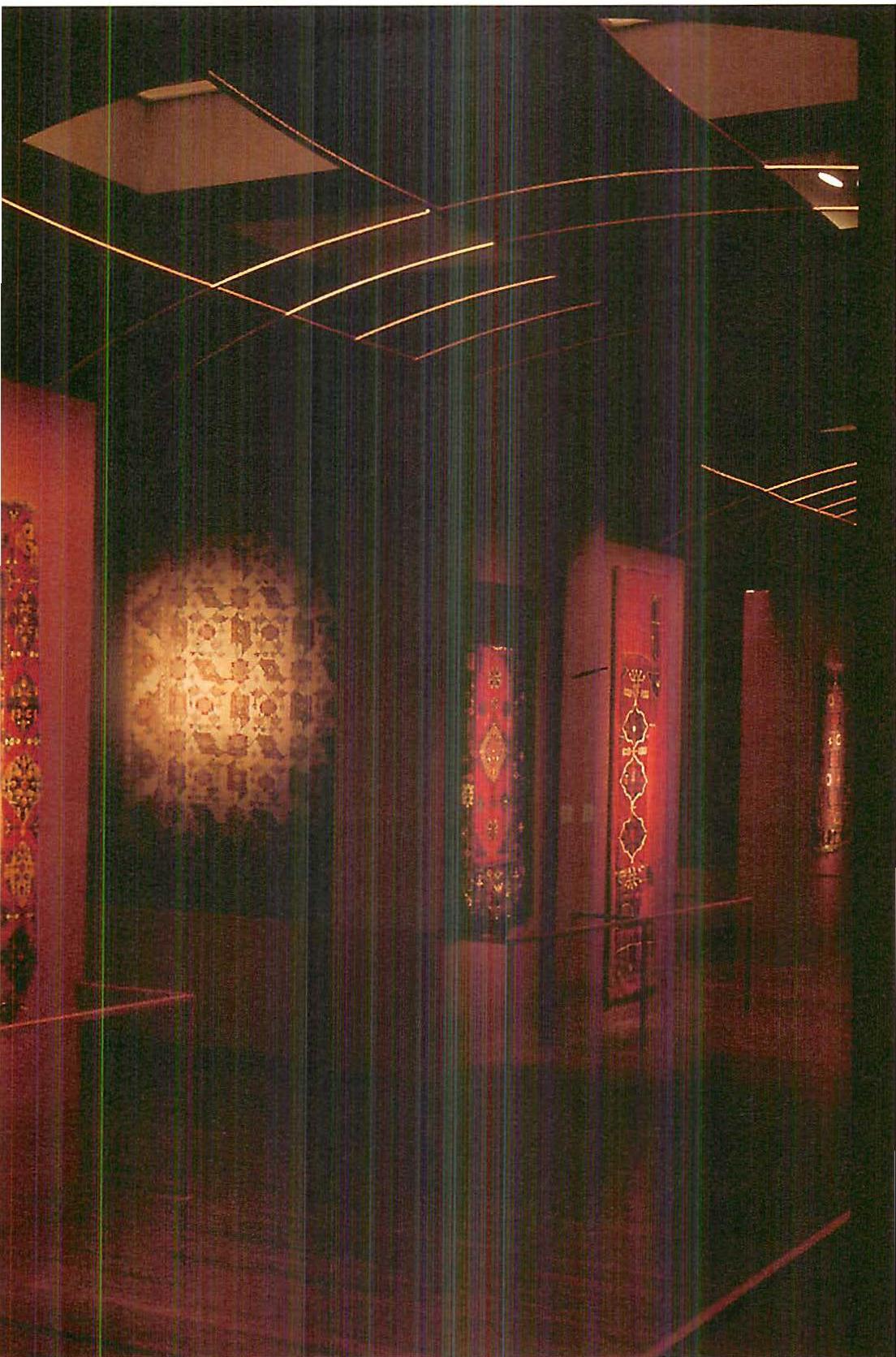

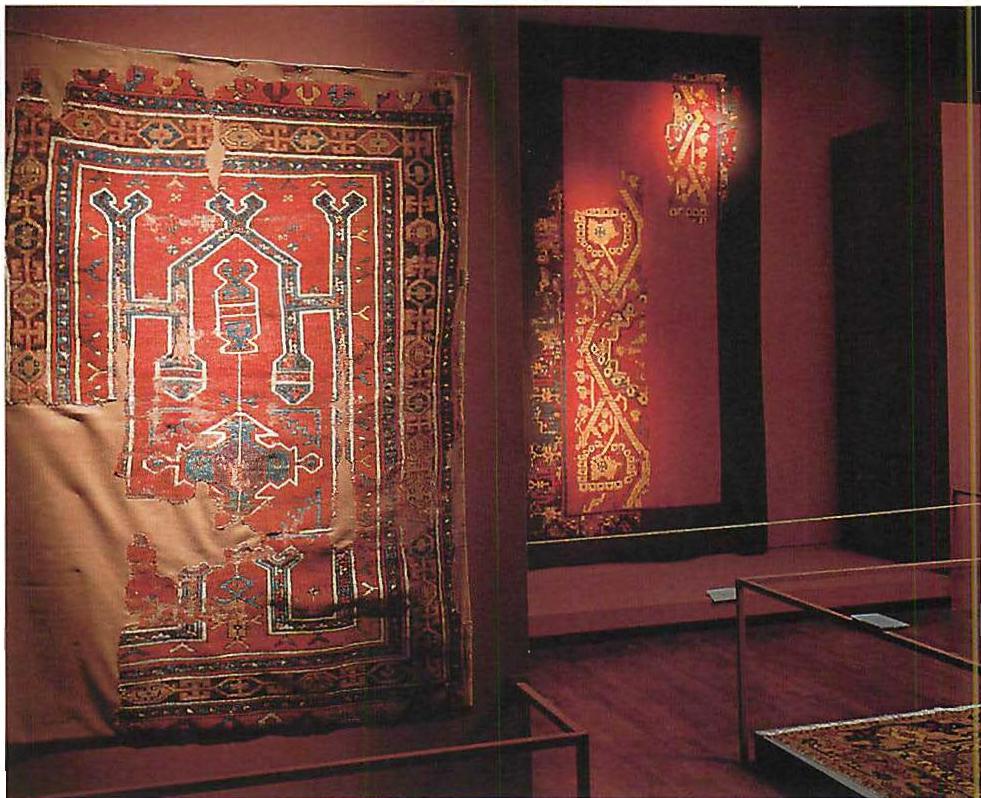

| Volume 7 | A FORESHADOWING OF 21ST CENTURY ART: |

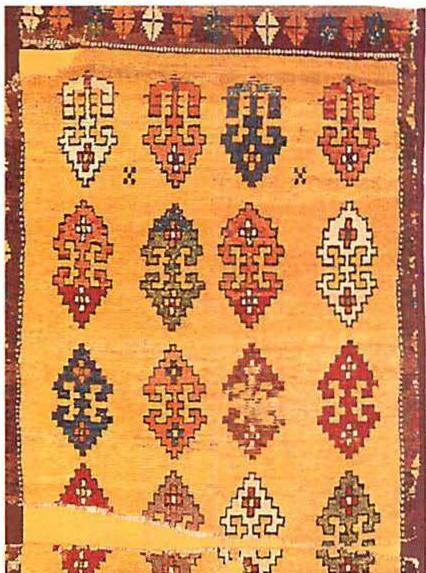

| THE COLOR AND GEOMETRY OF VERY EARLY TURKISH CARPETS | |

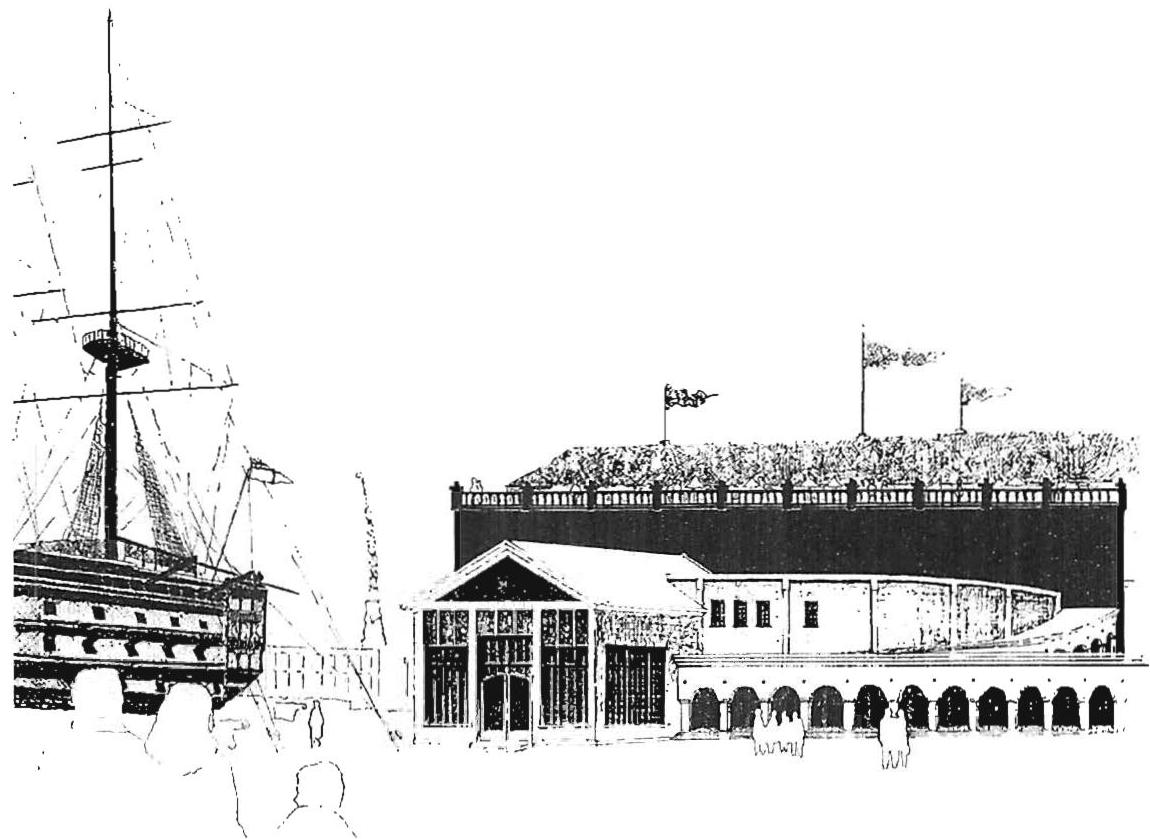

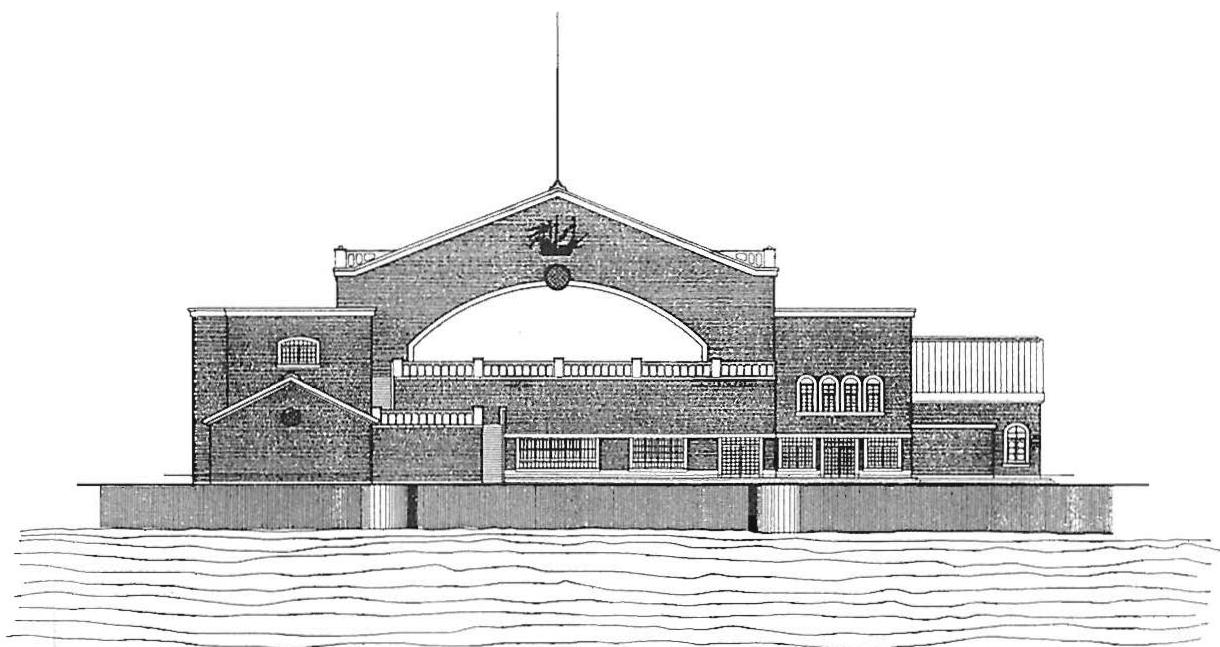

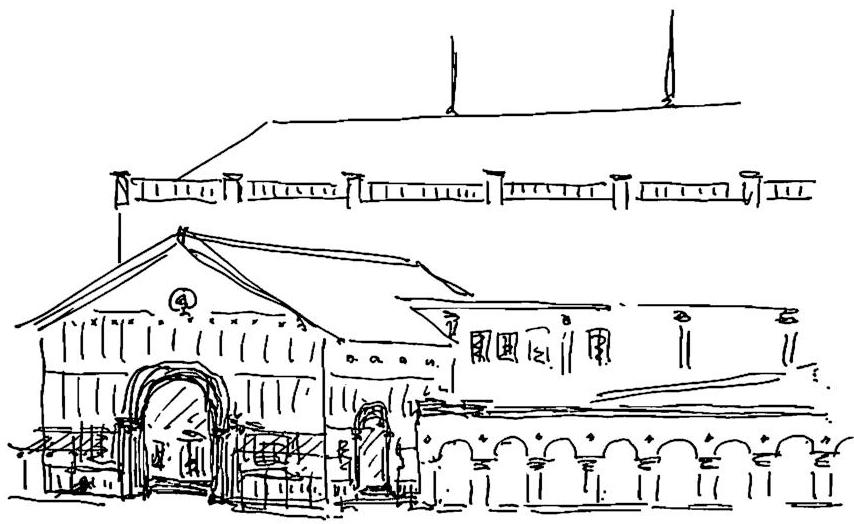

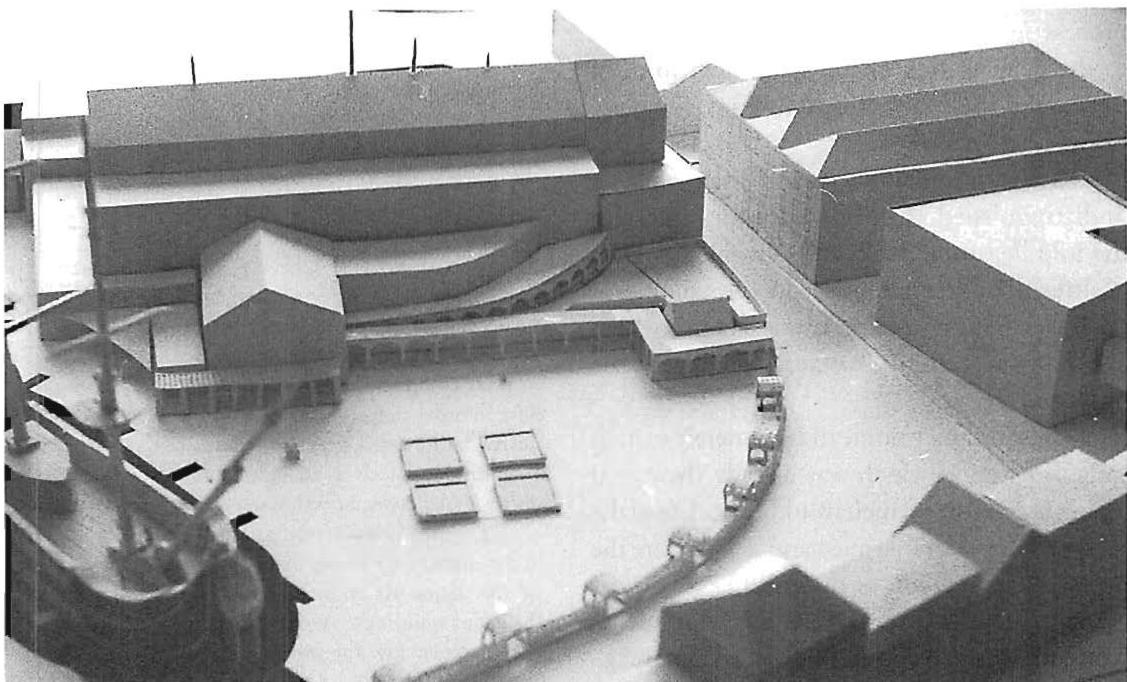

| Volume 8 | THE MARY ROSE MUSEUM |

| Volumes 9 to 12 | THE NATURE OF ORDER: AN ESSAY ON THE ART OF BUILDING |

| AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE | |

| Book 1 | THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE |

| Book 2 | THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE |

| Book 3 | A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD |

| Book 4 | THE LUMINOUS GROUND |

Future volume now in preparation

| Volume 13 | BATTLE: THE STORY OF A HISTORIC CLASH

BETWEEN WORLD SYSTEM A AND WORLD SYSTEM B | | --- | --- |

THE NATURE OF ORDER

An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe

BOOK ONE THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

BOOK TWO THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

BOOK THREE A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

BOOK FOUR THE LUMINOUS GROUND

THE CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL STRUCTURE in BERKELEY CALIFORNIA in association with PATTERNLANGUAGE.COM

© 2005 CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

PREVIOUS VERSIONS

© 1980, 1983, 1987, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

Published by The Center for Environmental Structure 2701 Shasta Road, Berkeley, California 94708

CES is a trademark of the Center for Environmental Structure. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Center for Environmental Structure.

ISBN 0-9726529-3-0 (Book 3) ISBN 0-9726529-0-6 (Set)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Alexander, Christopher. The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe / Christopher Alexander, p. cm. (Center for Environmental Structure Series; v. 9–12).

Contents: v.1. The Phenomenon of Life — v.2. The Process of Creating Life v.3. A Vision of a Living World — v.4. The Luminous Ground

- Architecture—Philosophy.

- Science—Philosophy.

- Cosmology

- Geometry in Architecture.

- Architecture—Case studies.

- Community

- Process philosophy.

- Color (Philosophy).

I. Center for Environmental Structure. II. Title. III. Title: A Vision of a Living World. IV. Series: Center for Environmental Structure series ; v. 11.

NA2500 .A444 2002 720’.1—dc21 2002154265 ISBN 0-9726529-3-0 (cloth: alk. paper: v.3)

Typography by Katalin Bende and Richard Wilson Manufactured in China by Everbest Printing Co., Ltd.

BOOK ONE: THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE

PROLOGUE TO BOOKS 1-4

THE ART OF BUILDING AND THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . 1

PREFACE: ON ORDER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

PART ONE

- THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

- DEGREES OF LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

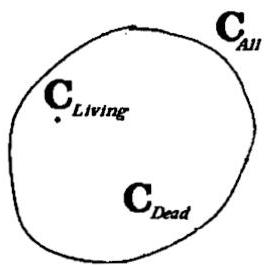

- WHOLENESS AND THE THEORY OF CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

- HOW LIFE COMES FROM WHOLENESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

- FIFTEEN FUNDAMENTAL PROPERTIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

- THE FIFTEEN PROPERTIES IN NATURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

PART TWO

- THE PERSONAL NATURE OF ORDER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

- THE MIRROR OF THE SELF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 313

- BEYOND DESCARTES: A NEW FORM OF SCIENTIFIC OBSERVATION . . . . 351

- THE IMPACT OF LIVING STRUCTURE ON HUMAN LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . 371

- THE AWAKENING OF SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 403

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 441

APPENDICES:

MATHEMATICAL ASPECTS OF WHOLENESS AND LIVING STRUCTURE . . . 445

BOOK TWO: THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE

PREFACE: ON PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

PART ONE: STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS

- THE PRINCIPLE OF UNFOLDING WHOLENESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

- STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

- STRUCTURE-PRESERVING TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRADITIONAL SOCIETY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

- STRUCTURE-DESTROYING TRANSFORMATIONS IN MODERN SOCIETY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

INTERLUDE

- LIVING PROCESS IN THE MODERN ERA: TWENTIETH-CENTURY CASES WHERE LIVING PROCESS DID OCCUR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

PART TWO: LIVING PROCESSES

- GENERATED STRUCTURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

- A FUNDAMENTAL DIFFERENTIATING PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203

- STEP-BY-STEP ADAPTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

- EACH STEP IS ALWAYS HELPING TO ENHANCE THE WHOLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 249

- ALWAYS MAKING CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 267

- THE SEQUENCE OF UNFOLDING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 299

- EVERY PART UNIQUE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 323

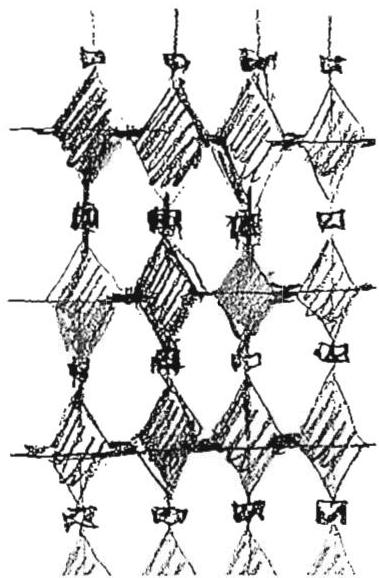

- PATTERNS: GENERIC RULES FOR MAKING CENTERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 341

- DEEP FEELING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369

- EMERGENCE OF FORMAL GEOMETRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 401

- FORM LANGUAGE AND STYLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 431

- SIMPLICITY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 461

PART THREE: A NEW PARADIGM FOR PROCESS IN SOCIETY

- ENCOURAGING FREEDOM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 495

- MASSIVE PROCESS DIFFICULTIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 511

- THE SPREAD OF LIVING PROCESSES THROUGHOUT SOCIETY: MAKING THE SHIFT TO THE NEW PARADIGM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 531

- THE ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT IN THE THIRD MILLENIUM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 551

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 565 APPENDIX: A SMALL EXAMPLE OF A LIVING PROCESS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 571

BOOK THREE: A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

PREFACE: LIVING PROCESSES REPEATED TEN MILLION TIMES . . . . . 1

PART ONE

- BELONGING AND NOT-BELONGING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

- OUR BELONGING TO THE WORLD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

PART TWO

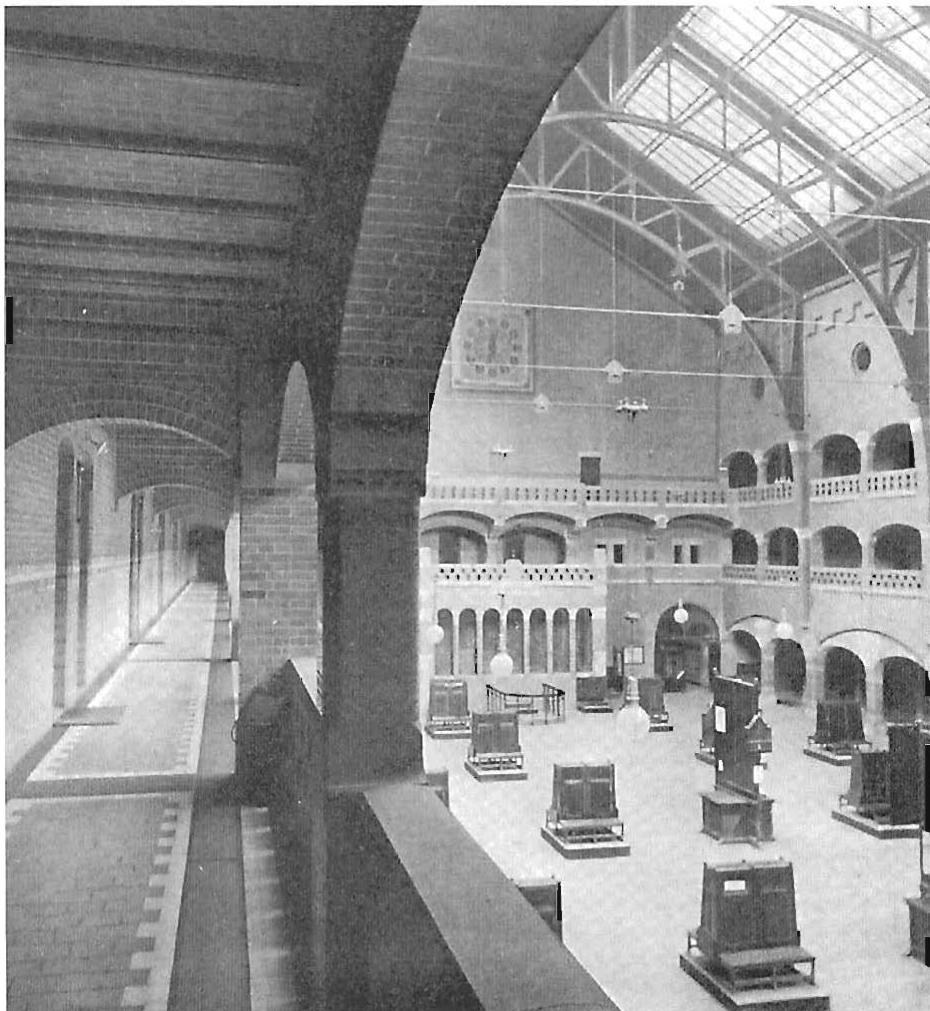

- THE HULLS OF PUBLIC SPACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

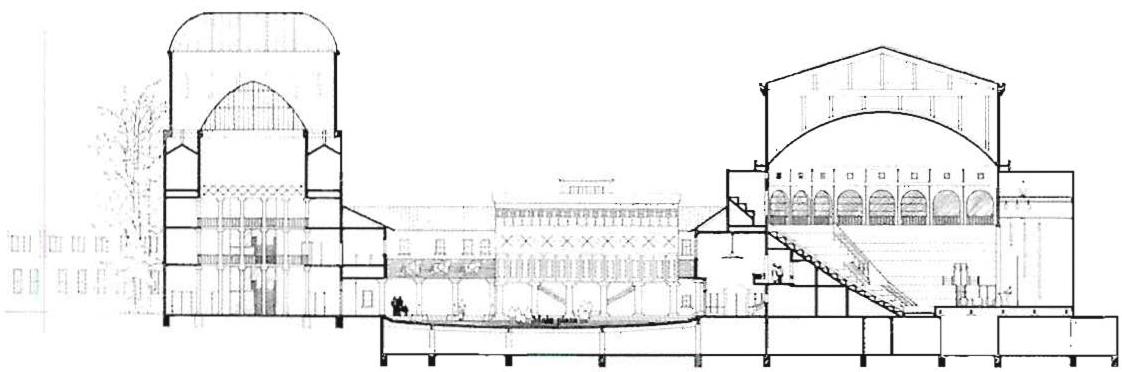

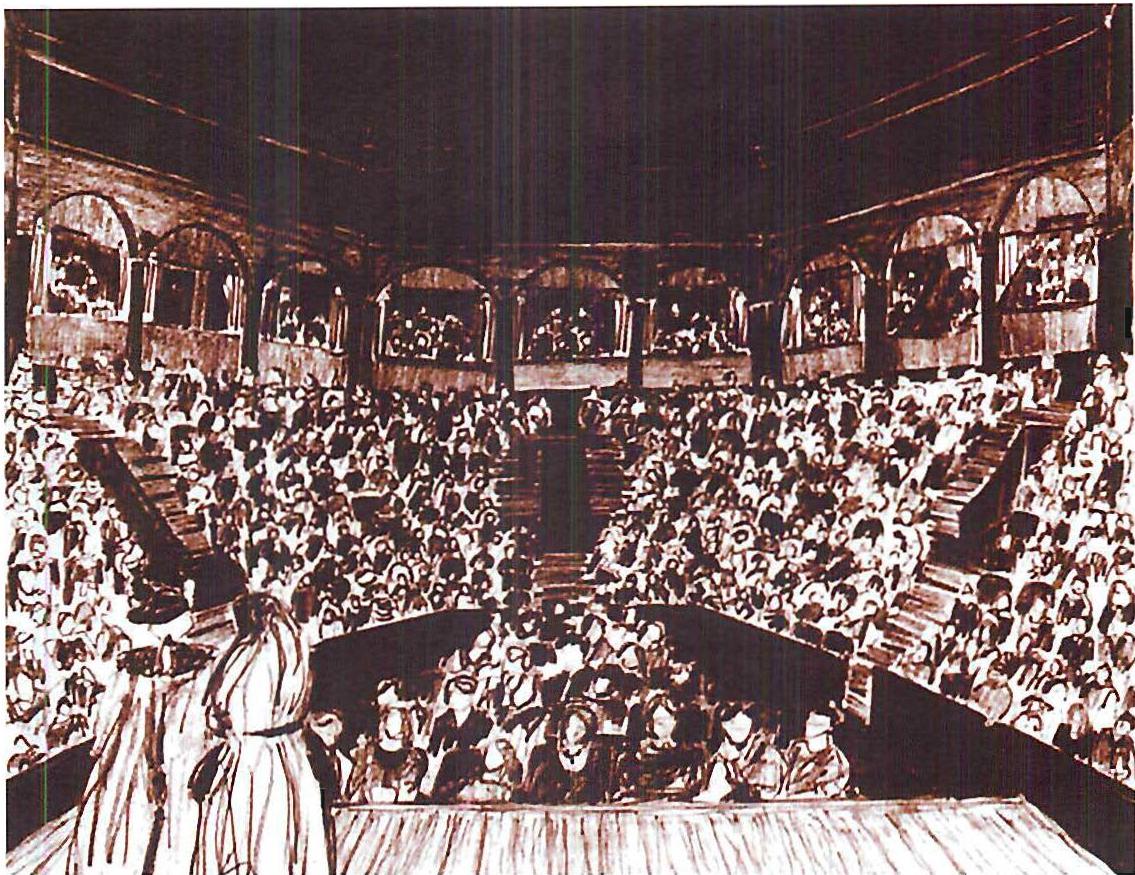

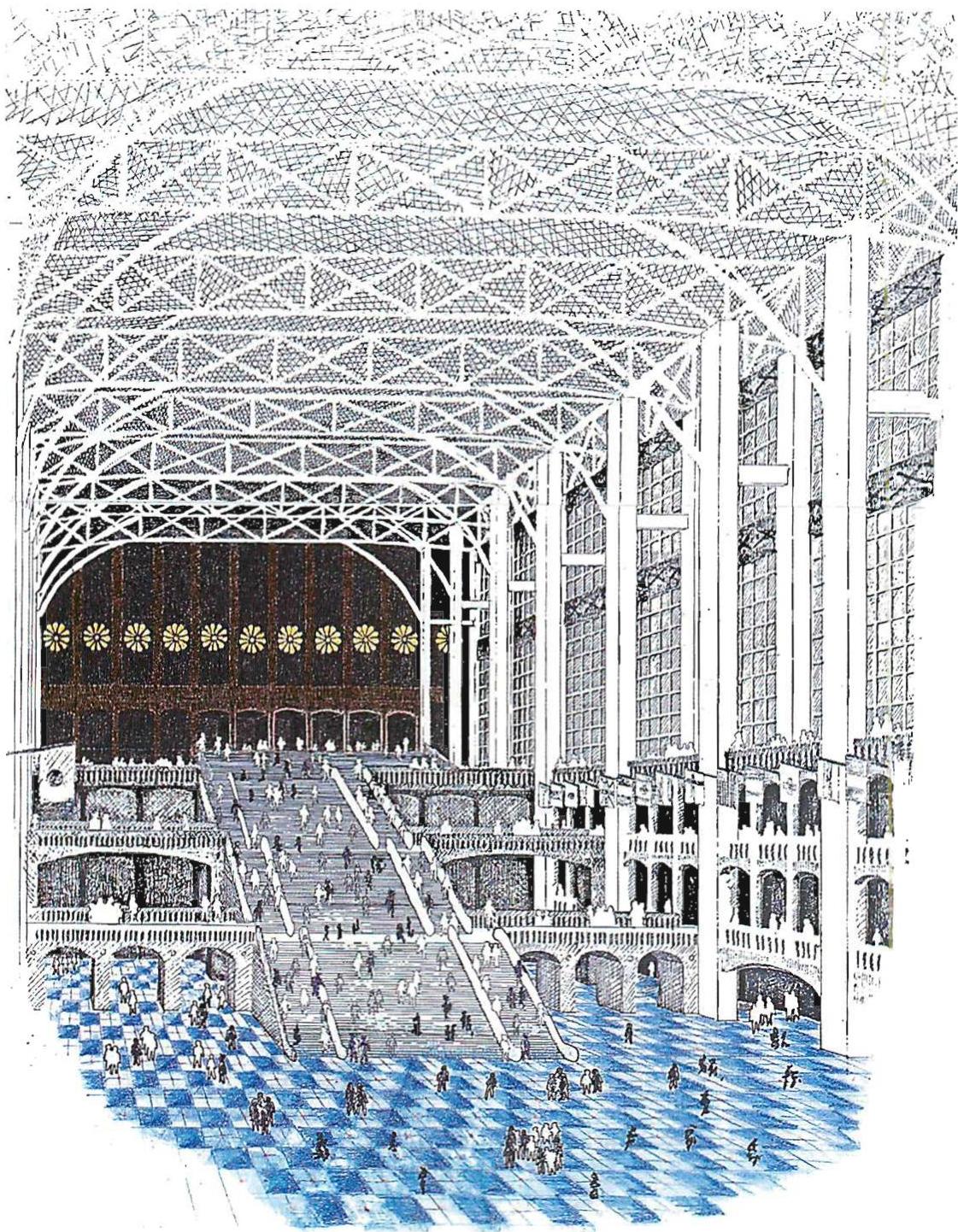

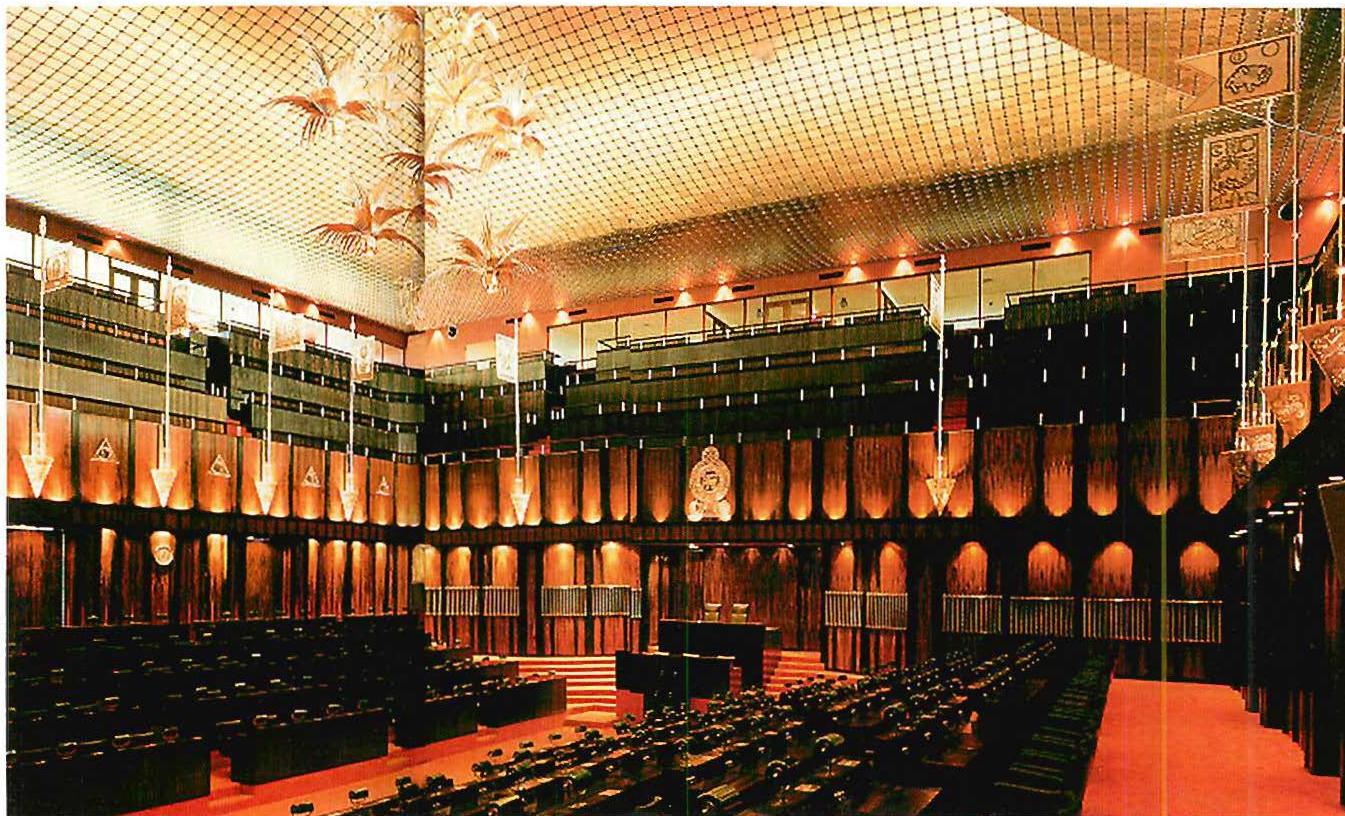

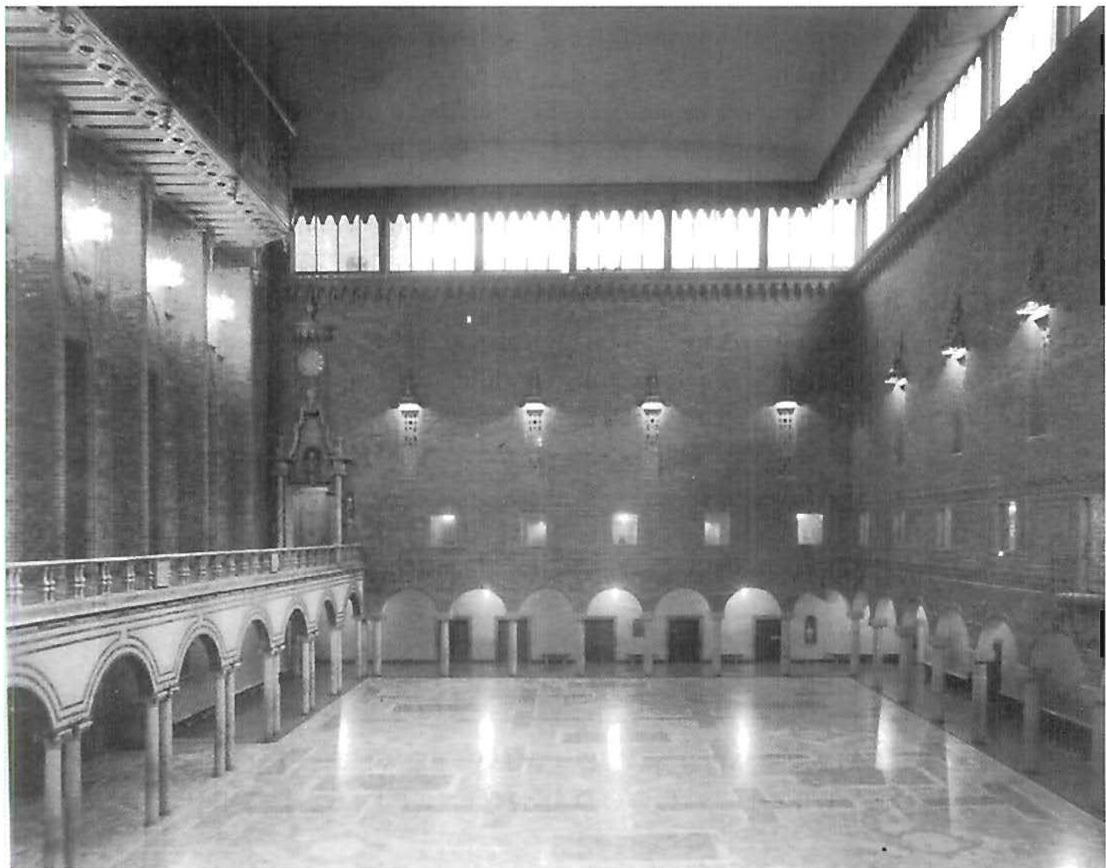

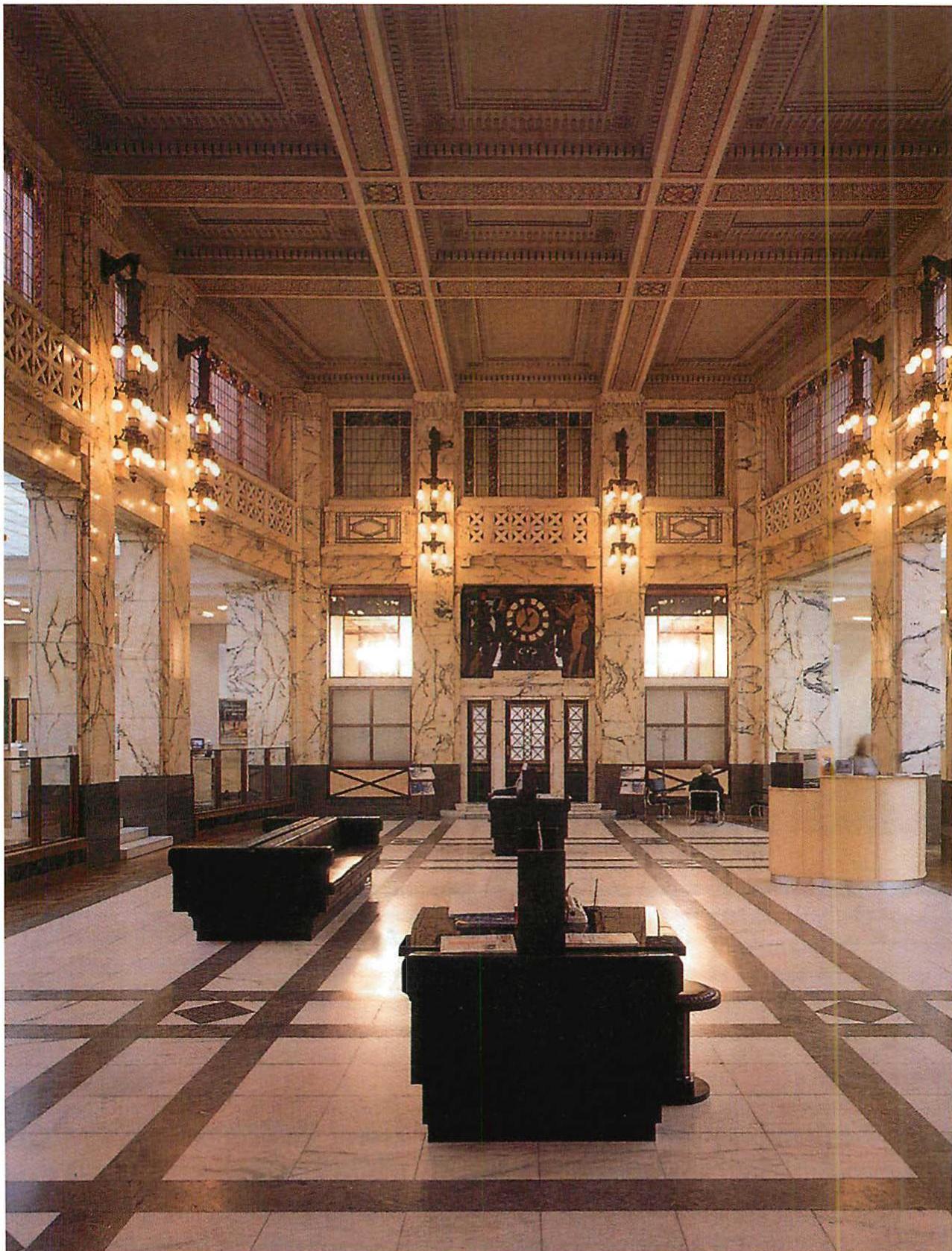

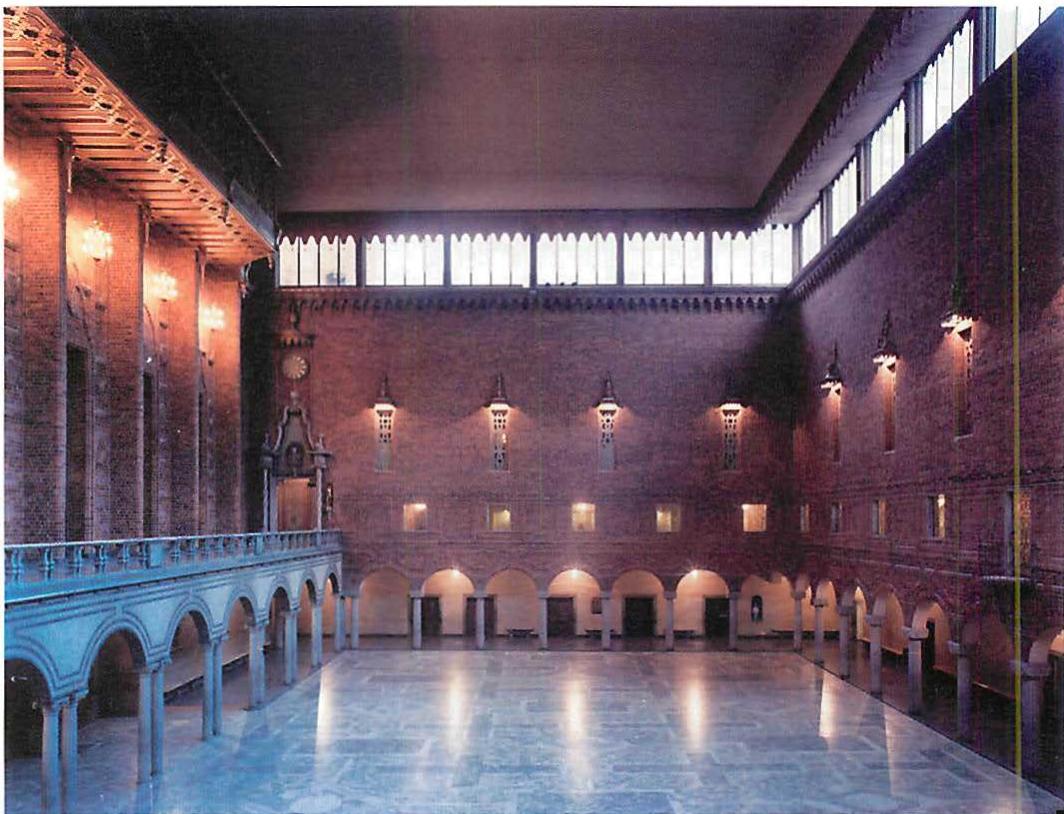

- LARGE PUBLIC BUILDINGS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

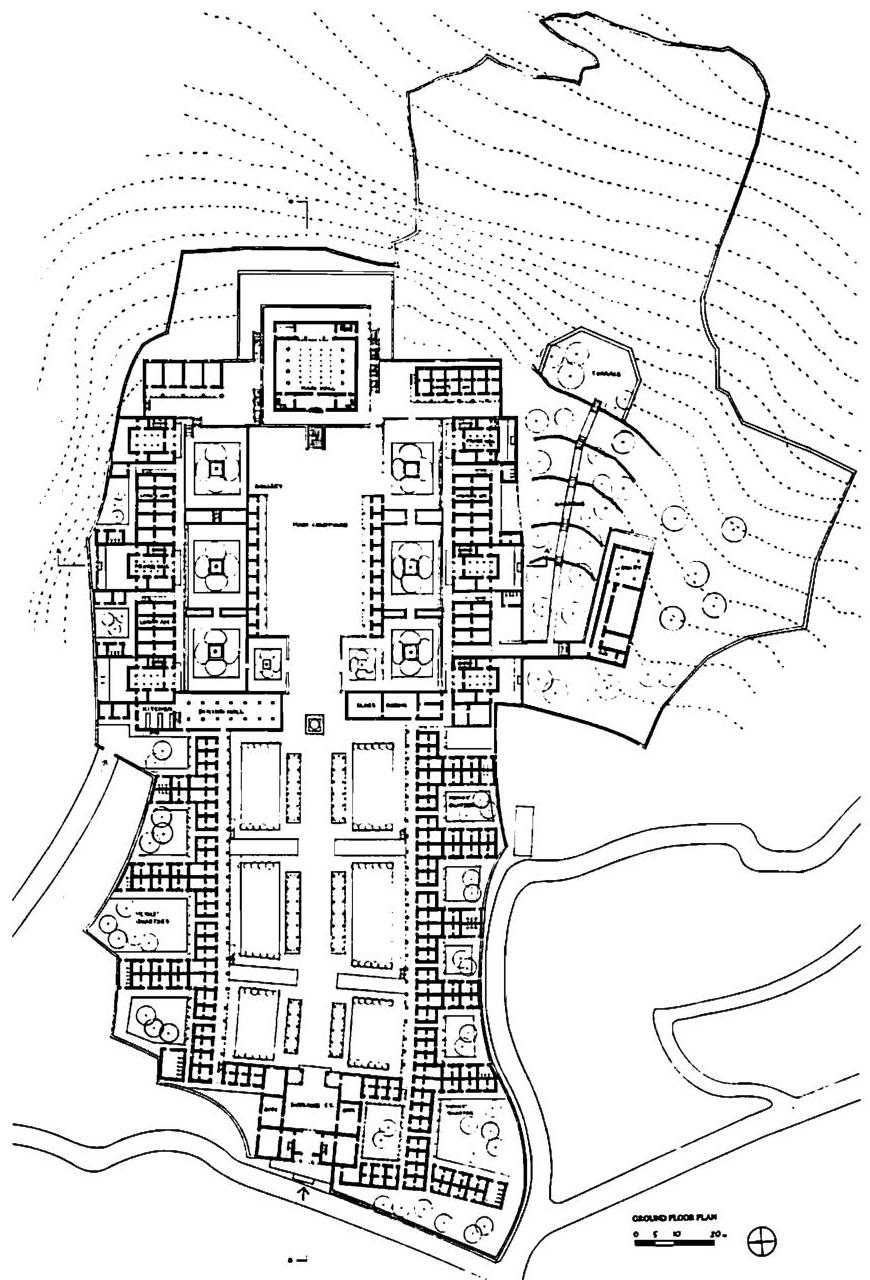

- THE POSITIVE PATTERN OF SPACE AND VOLUME IN THREE DIMENSIONS ON THE LAND . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

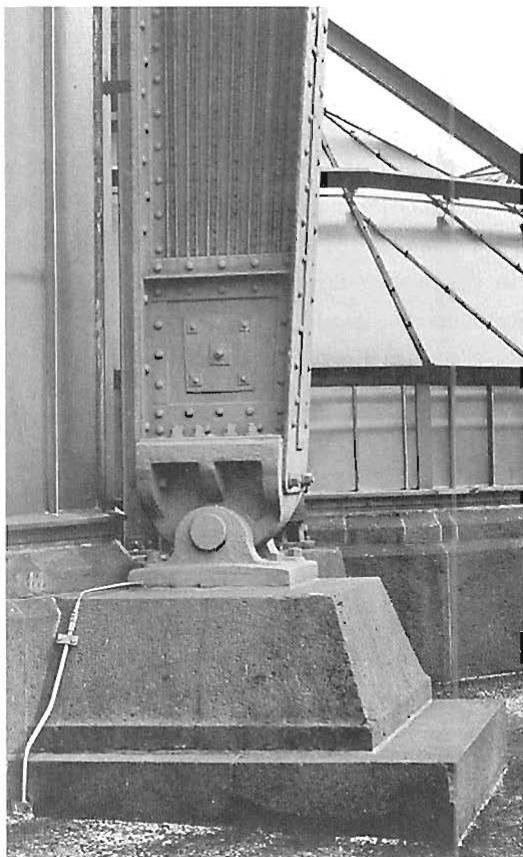

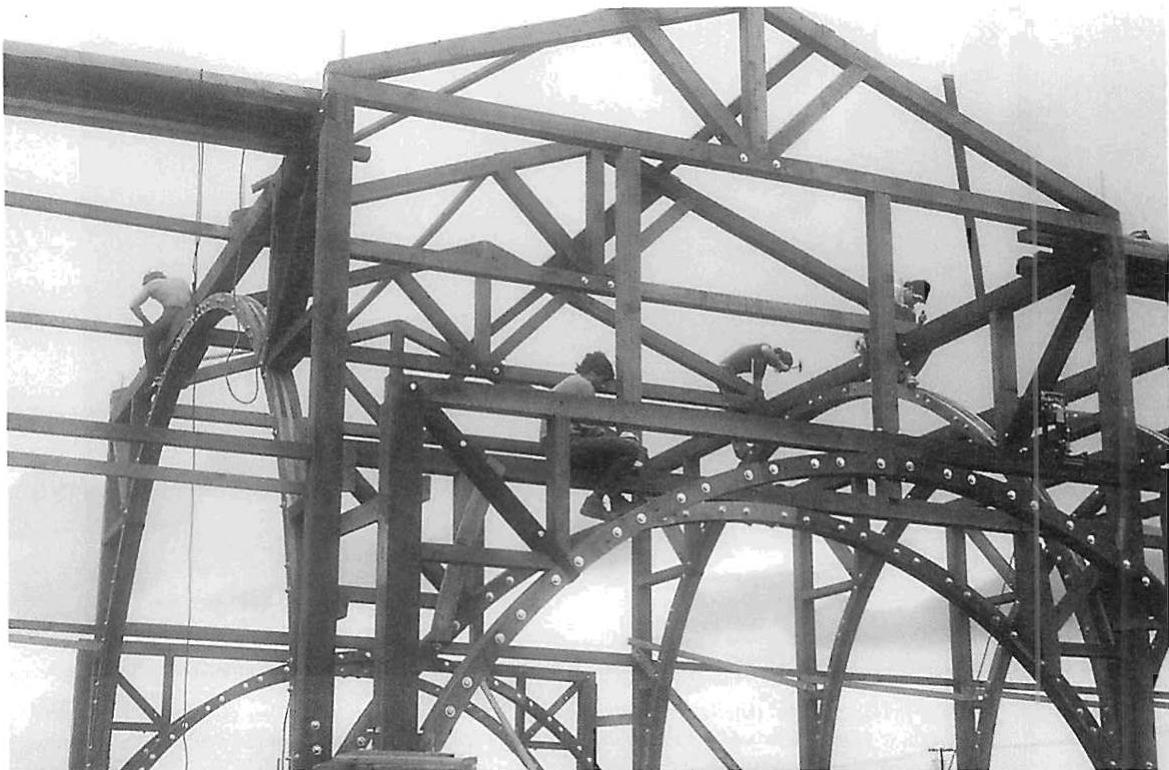

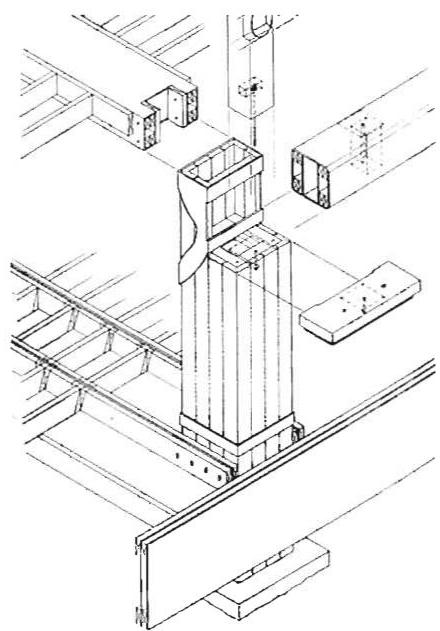

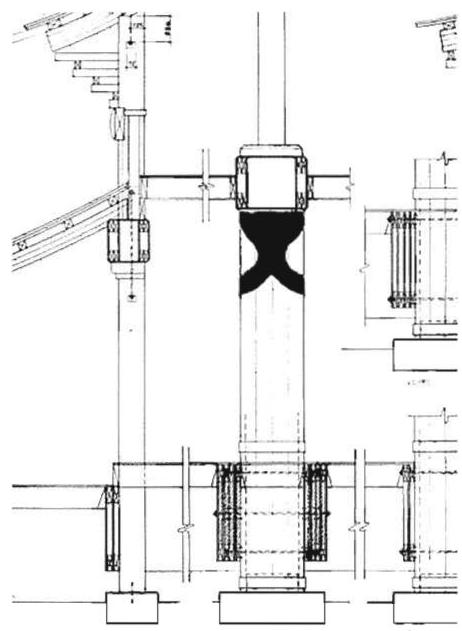

- POSITIVE SPACE IN ENGINEERING STRUCTURE AND GEOMETRY . . . 191

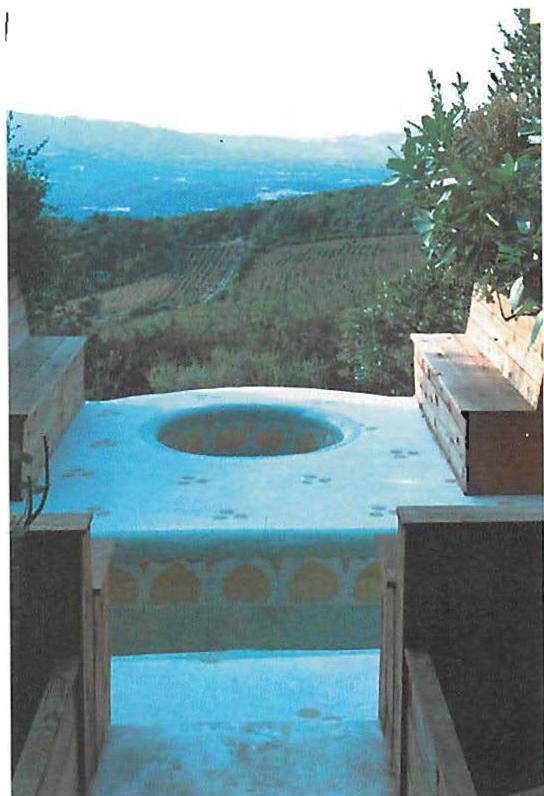

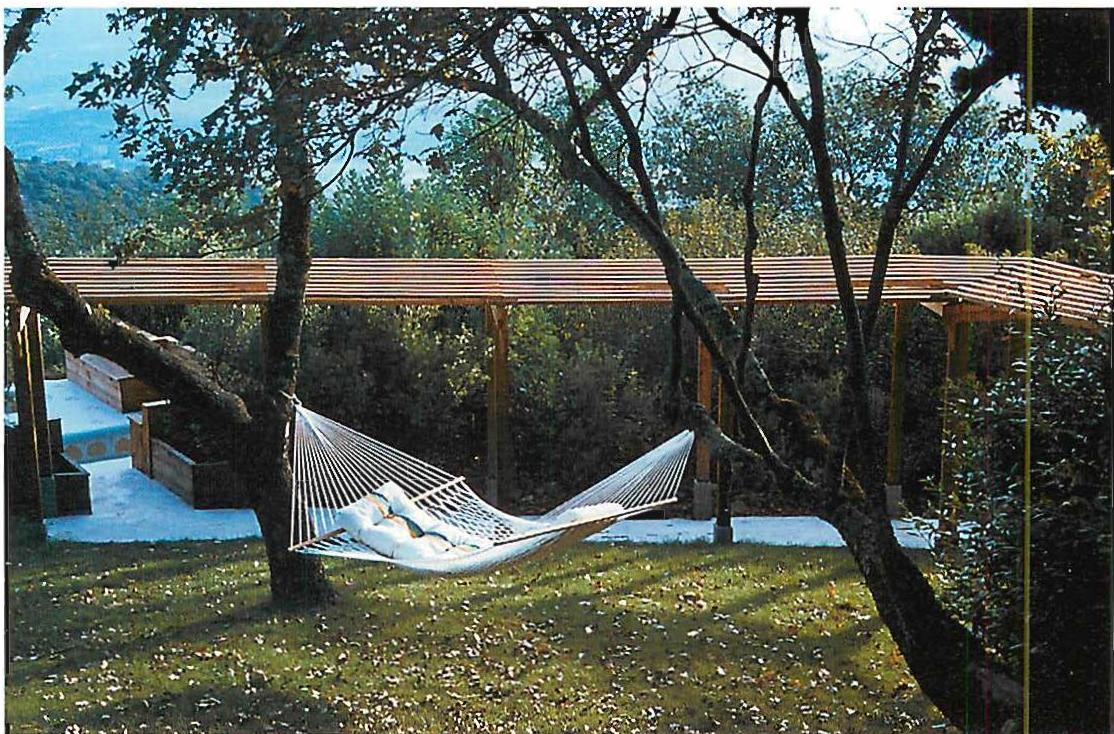

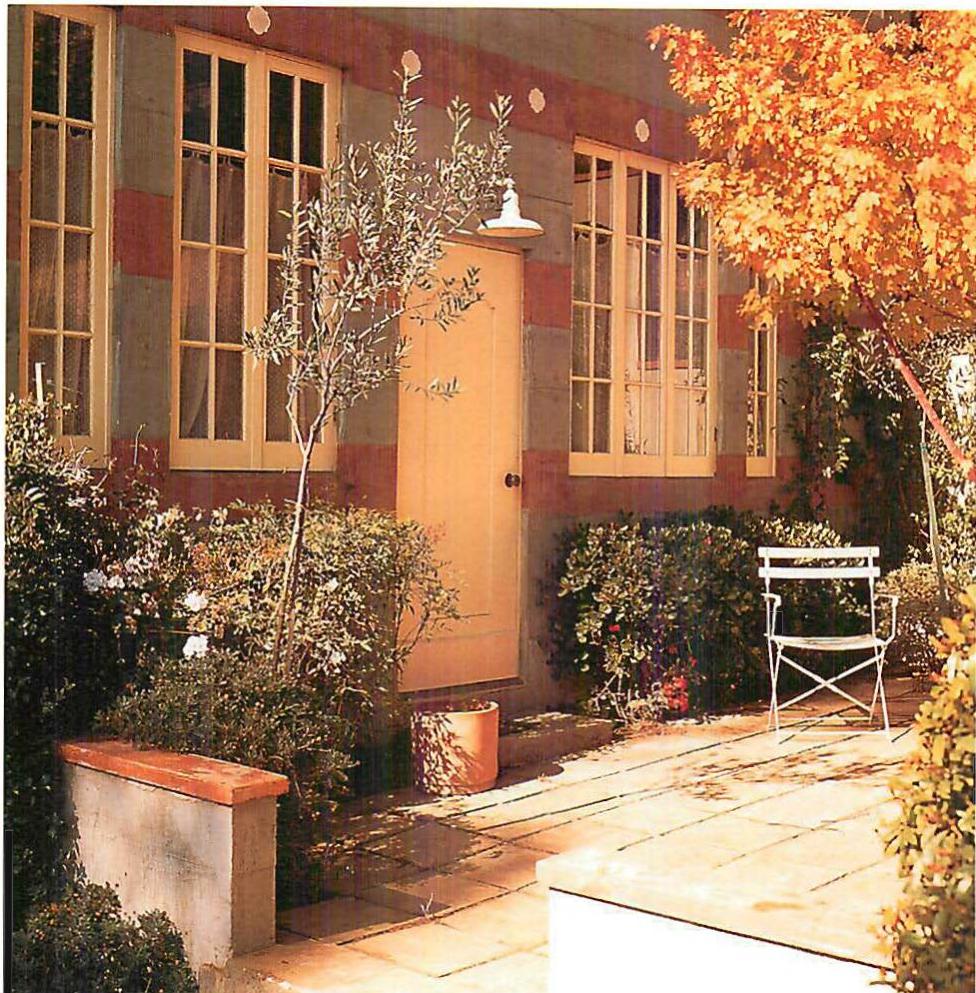

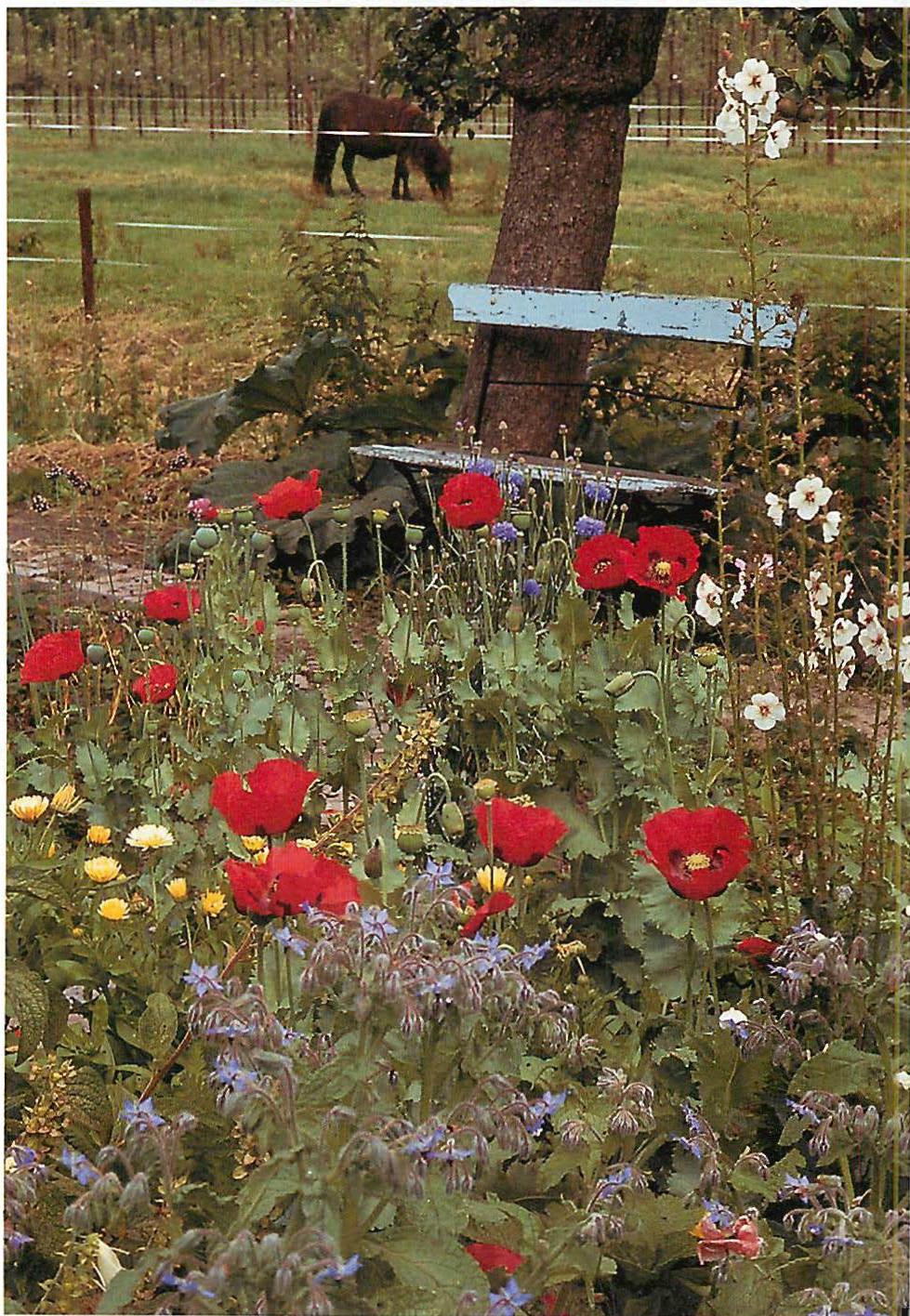

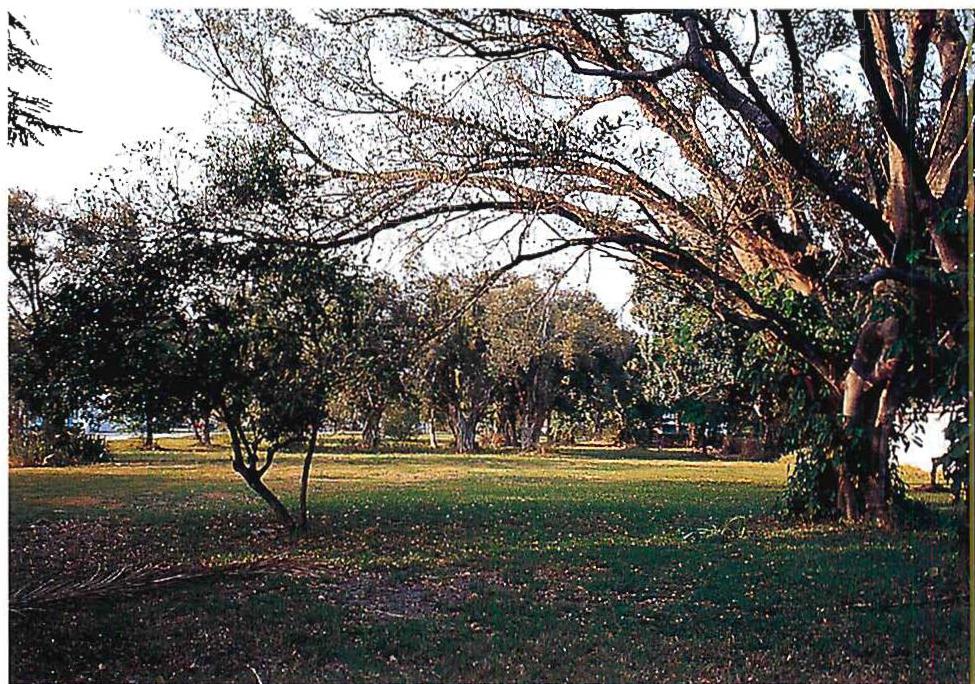

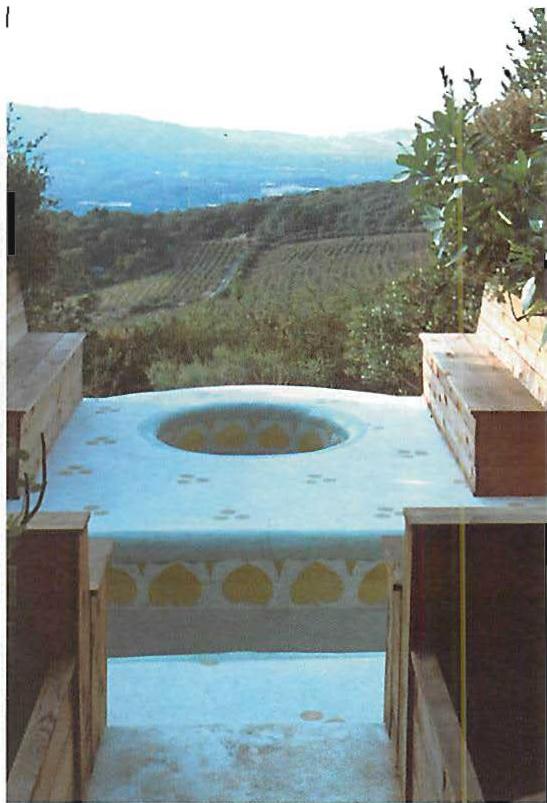

- THE CHARACTER OF GARDENS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 229

PART THREE

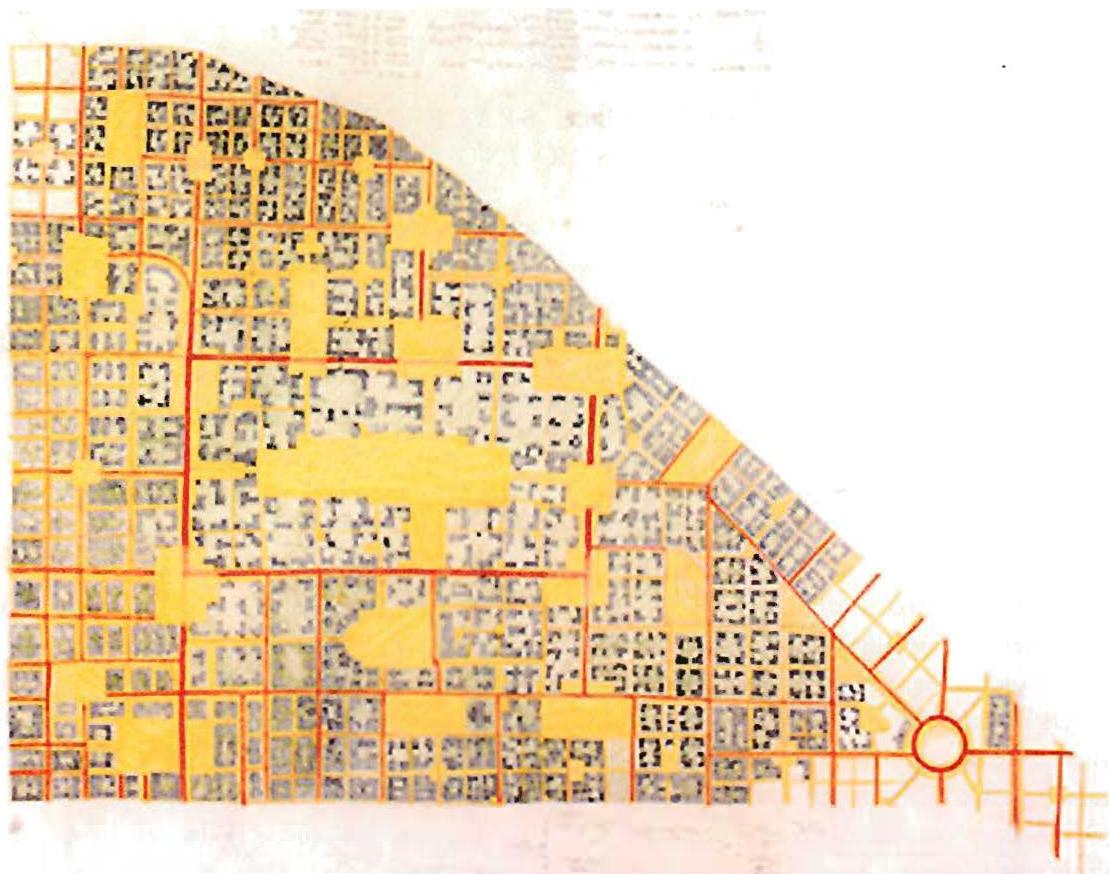

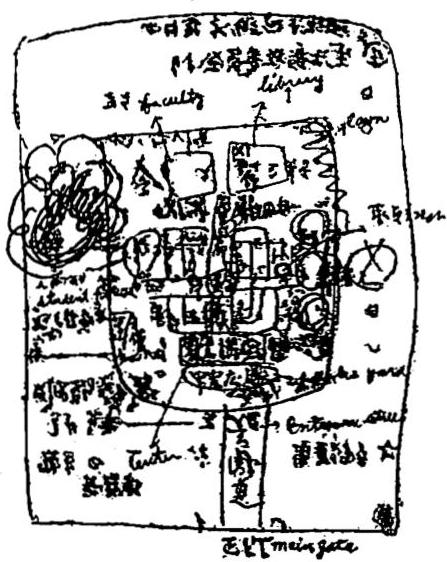

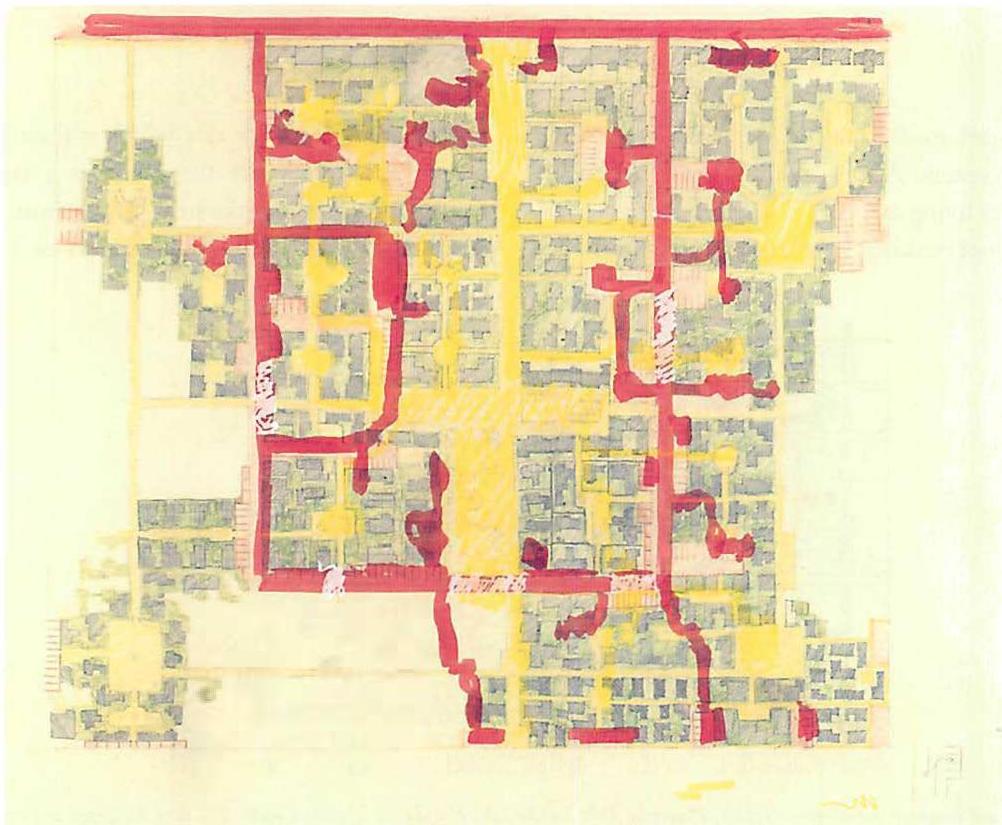

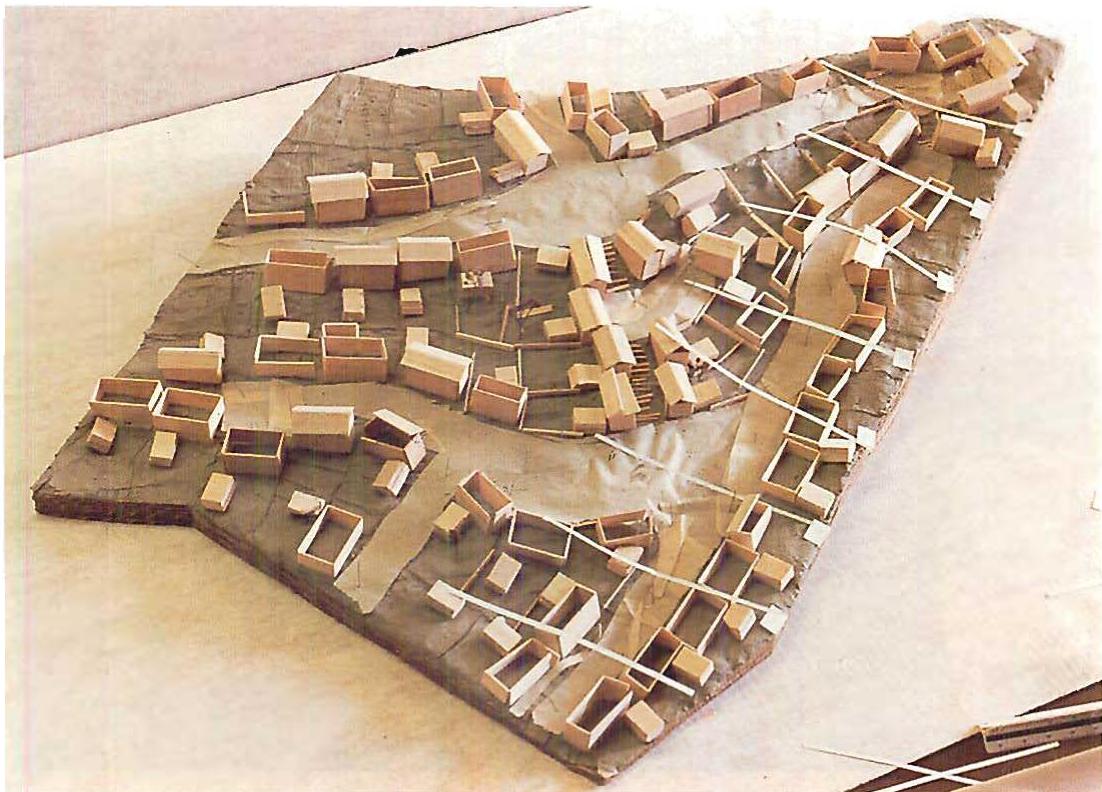

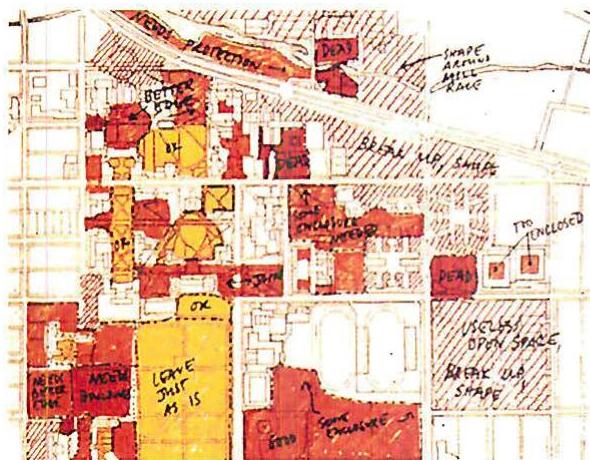

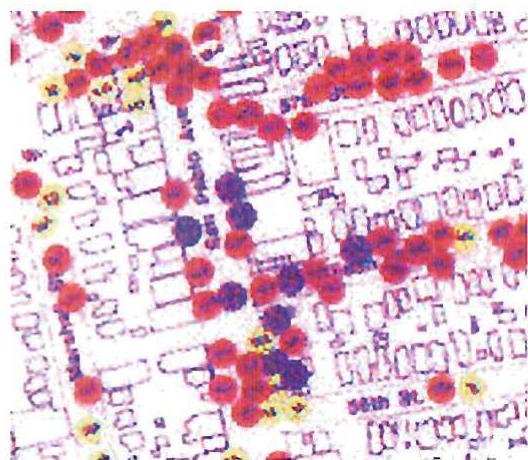

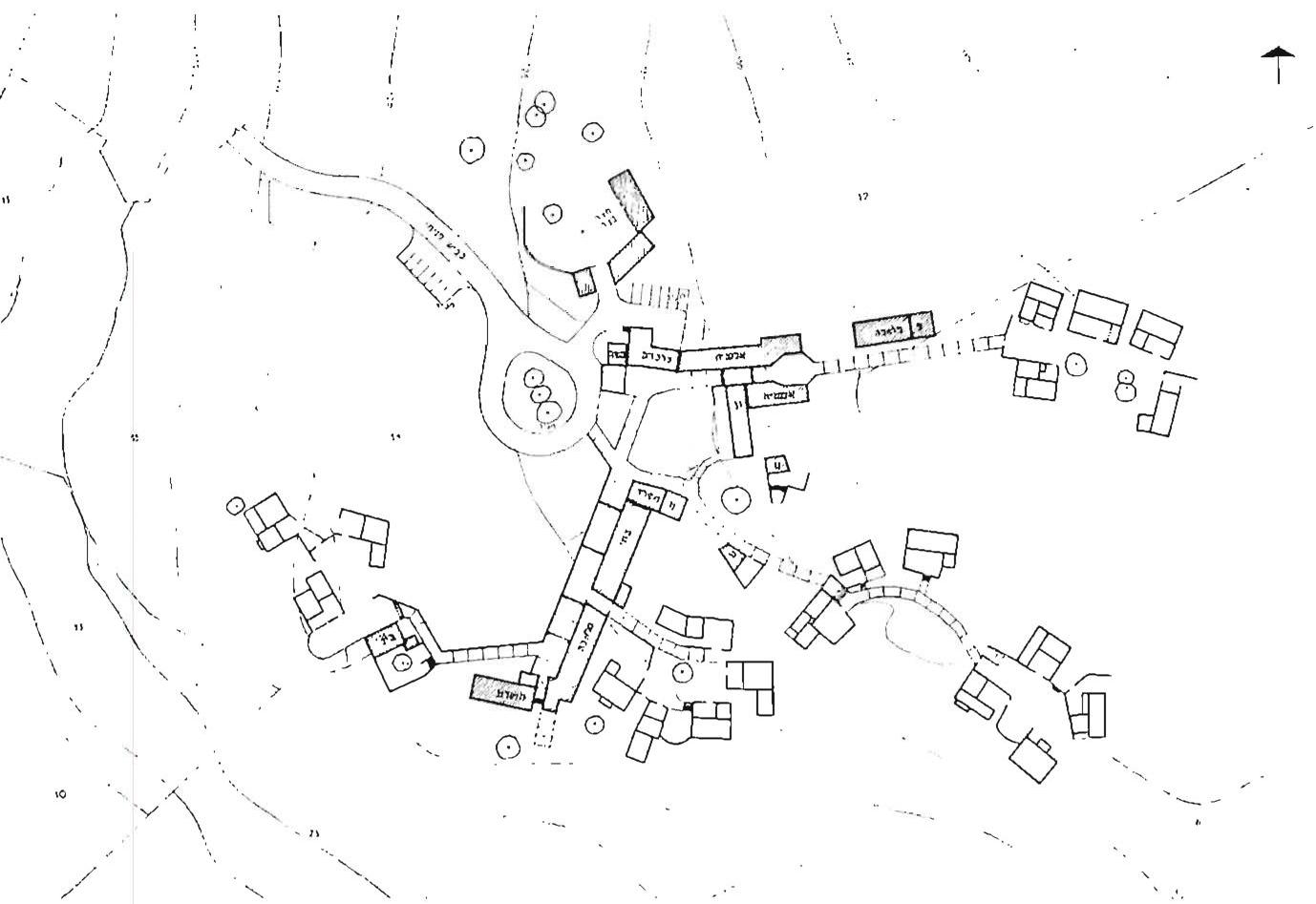

- PEOPLE FORMING A COLLECTIVE VISION FOR THEIR NEIGHBORHOOD . 257

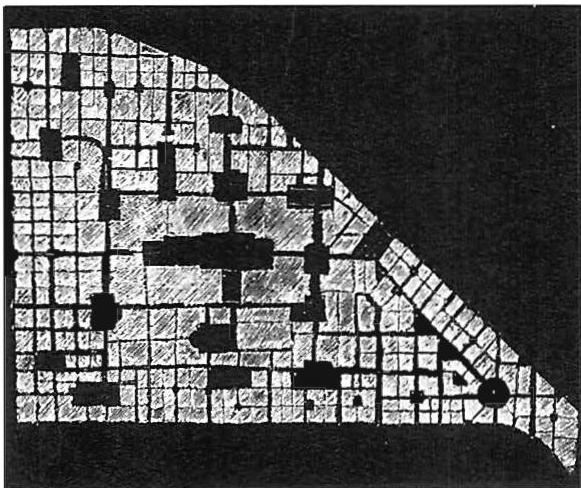

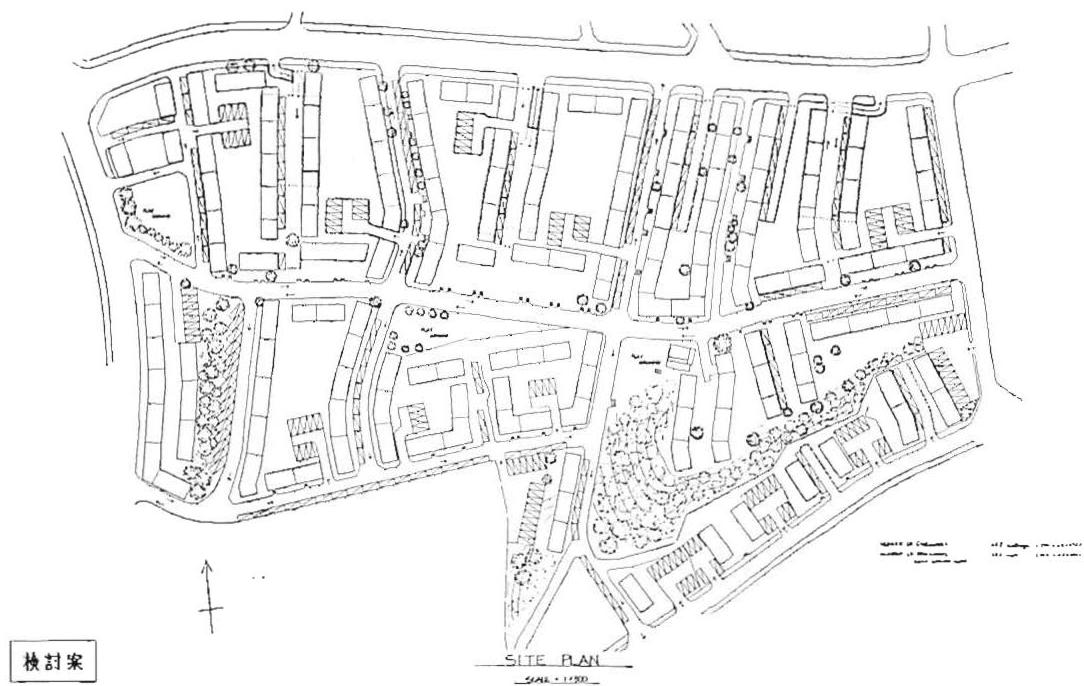

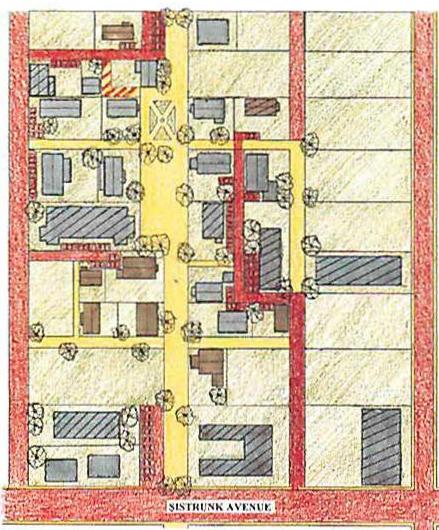

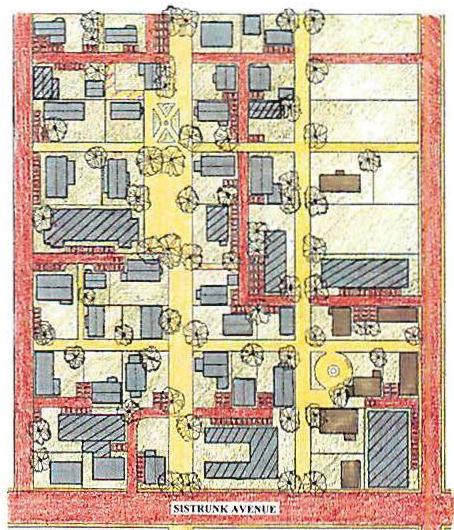

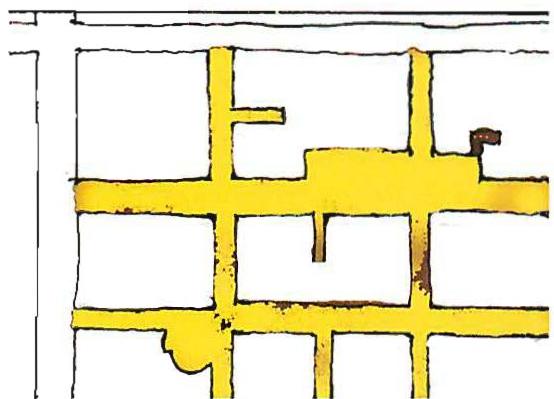

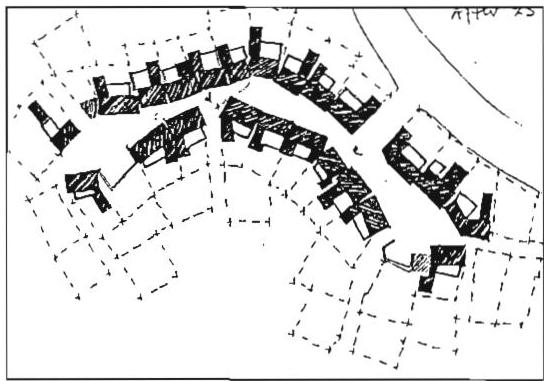

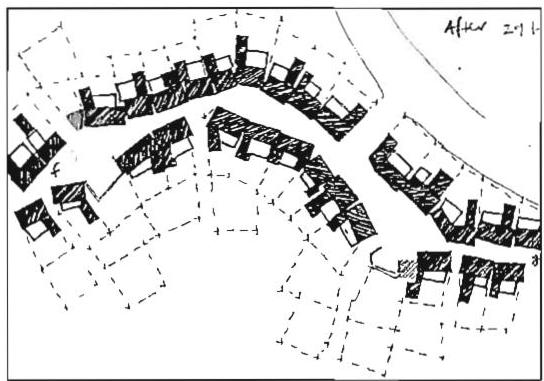

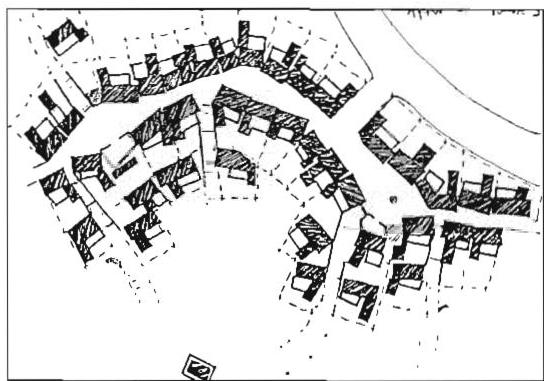

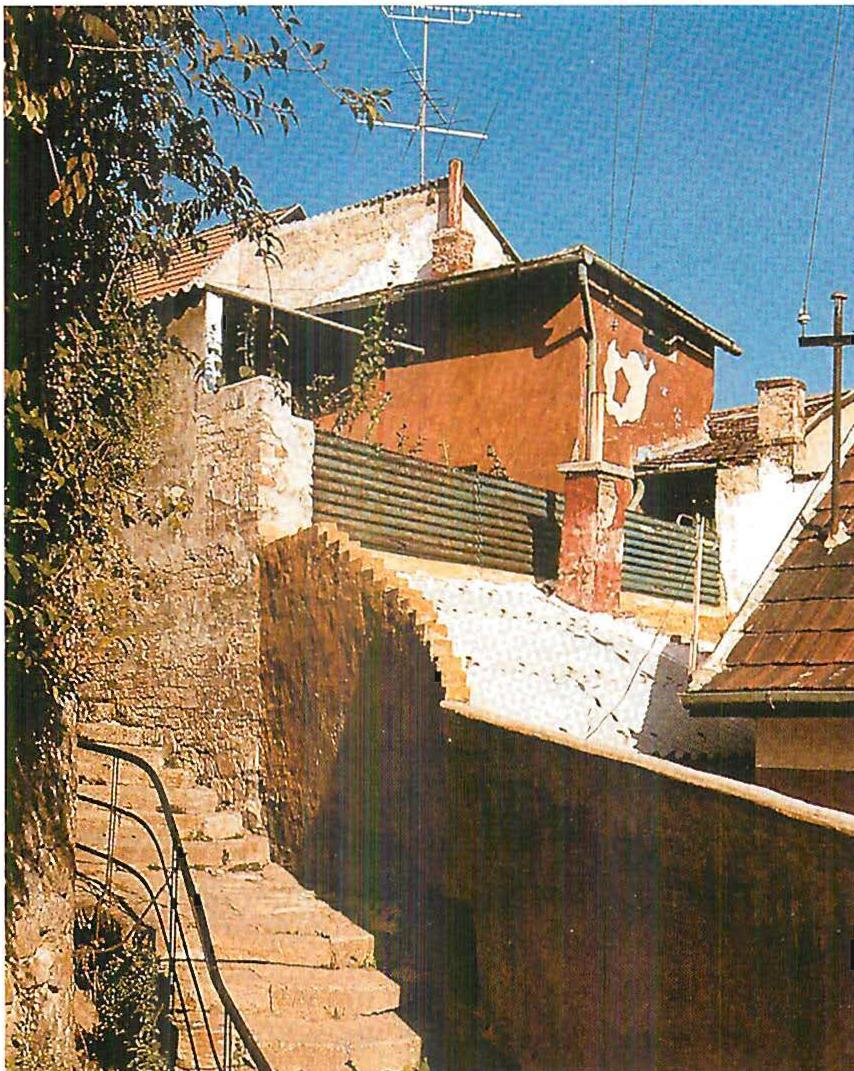

- RECONSTRUCTION OF AN URBAN NEIGHBORHOOD . . . . . . . . 283

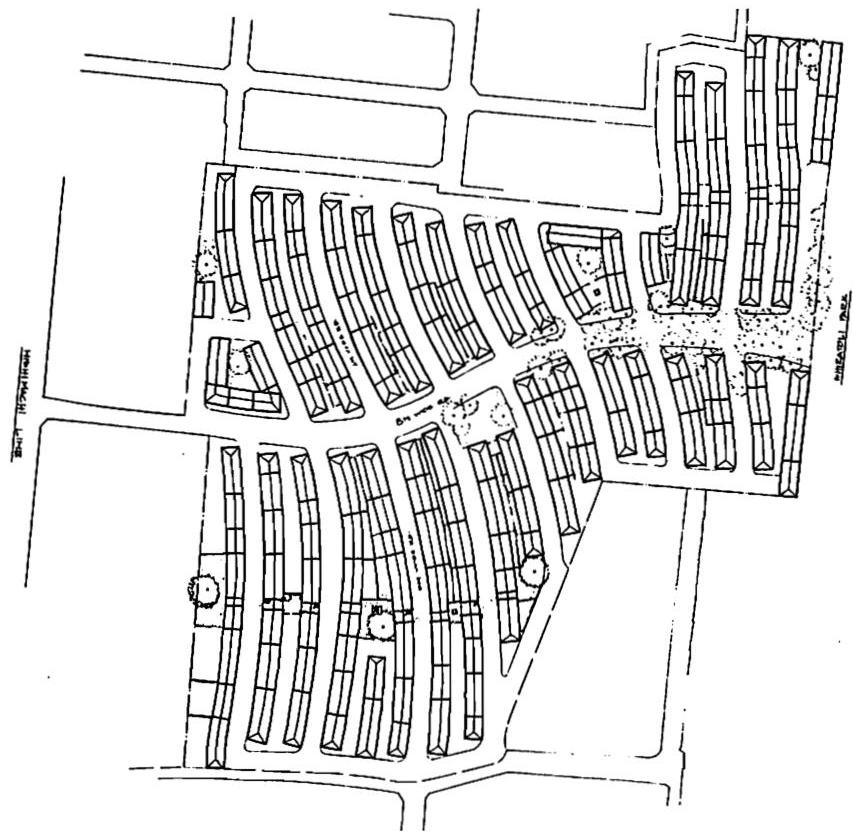

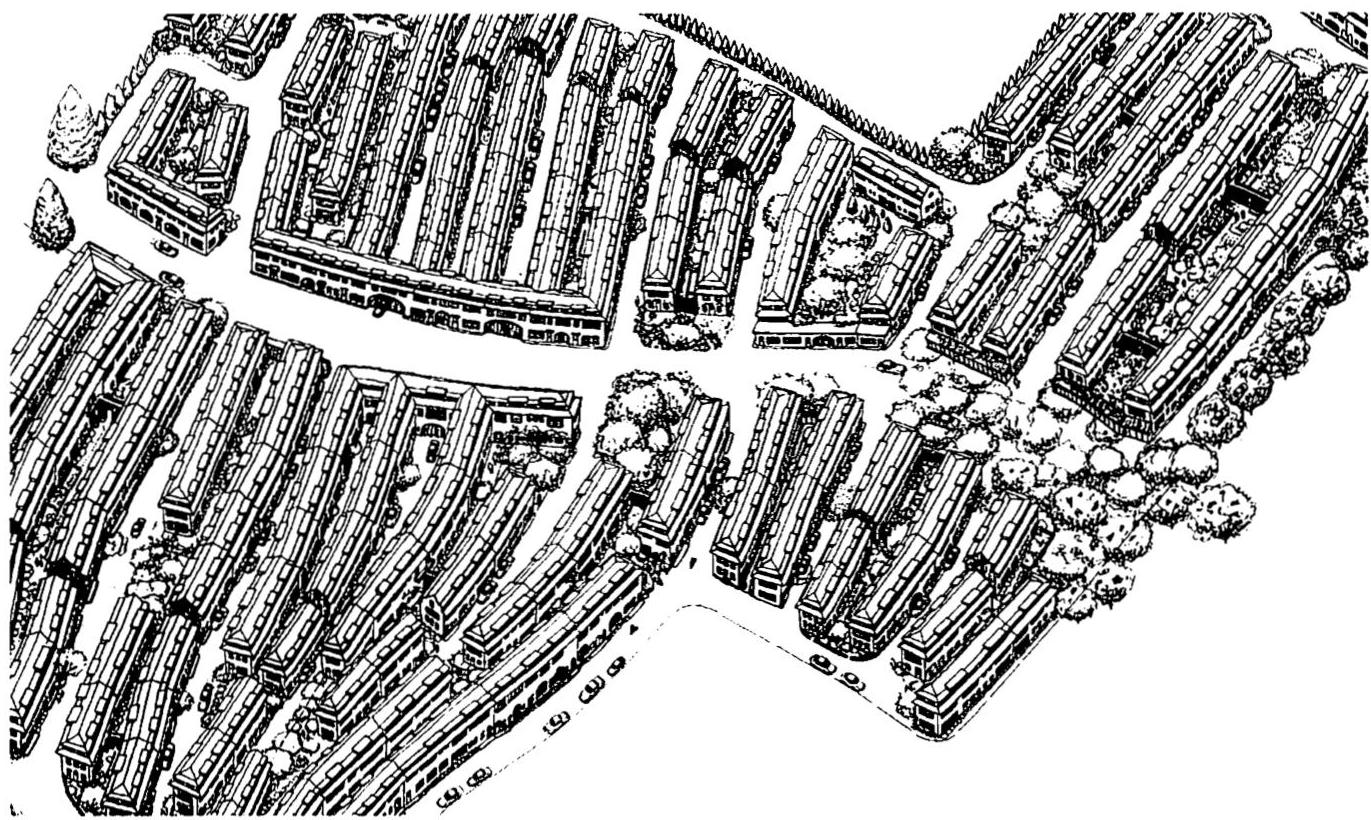

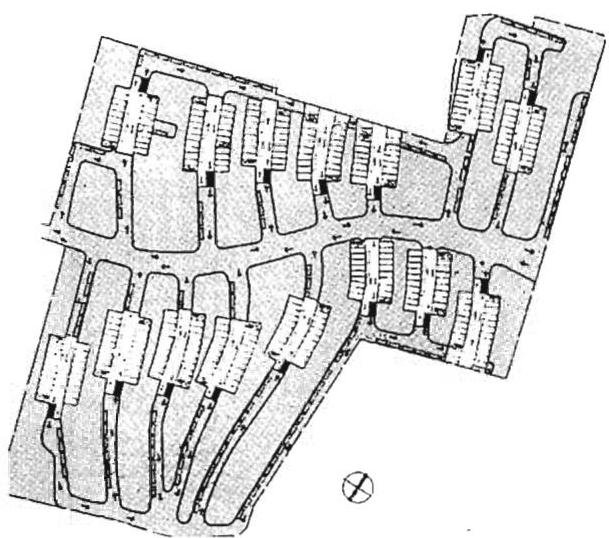

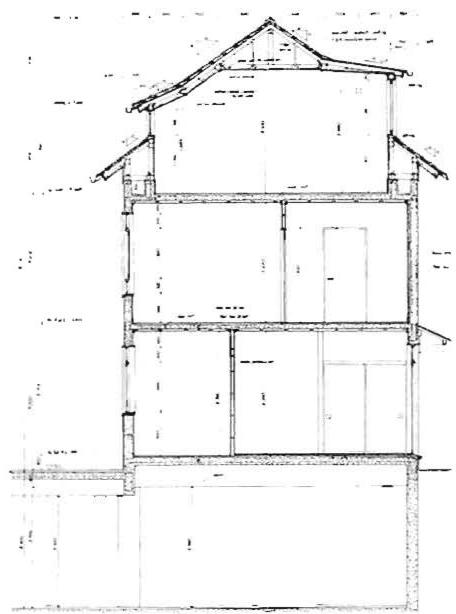

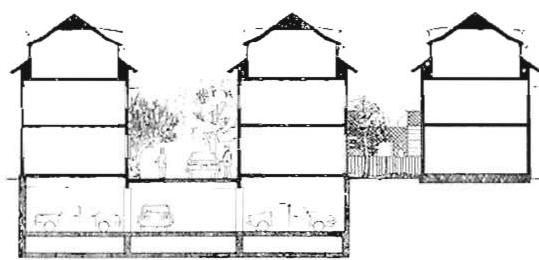

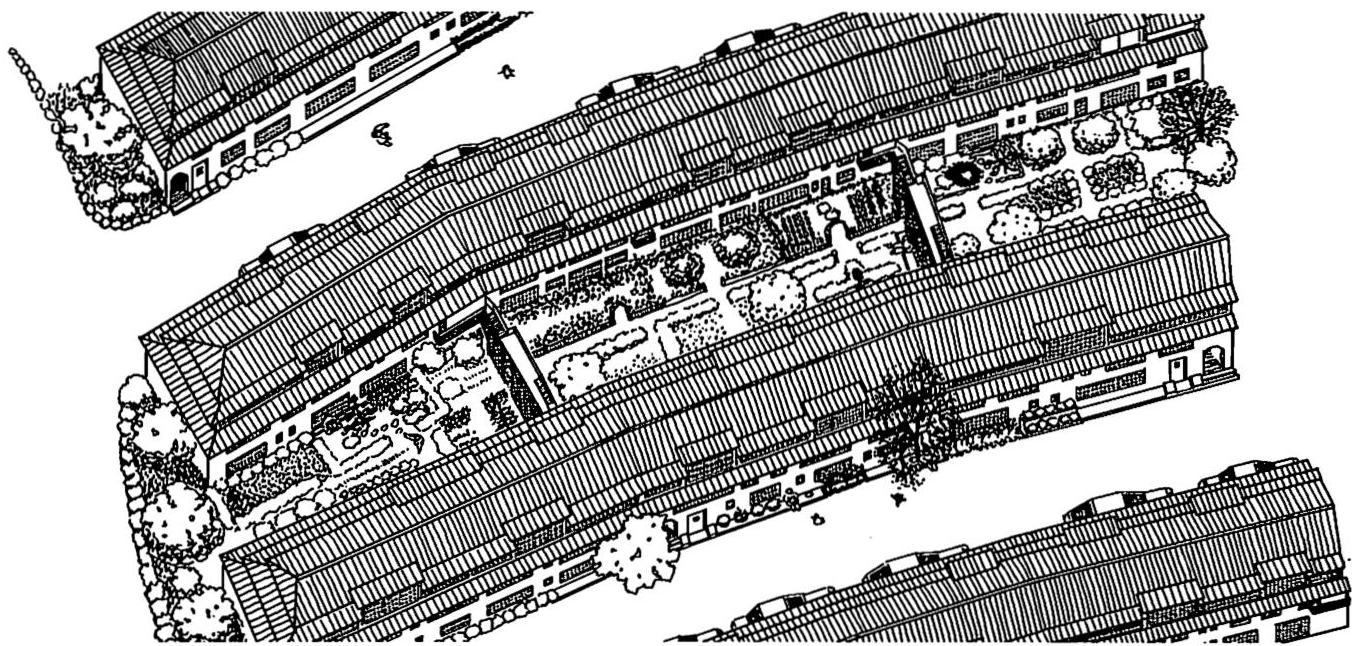

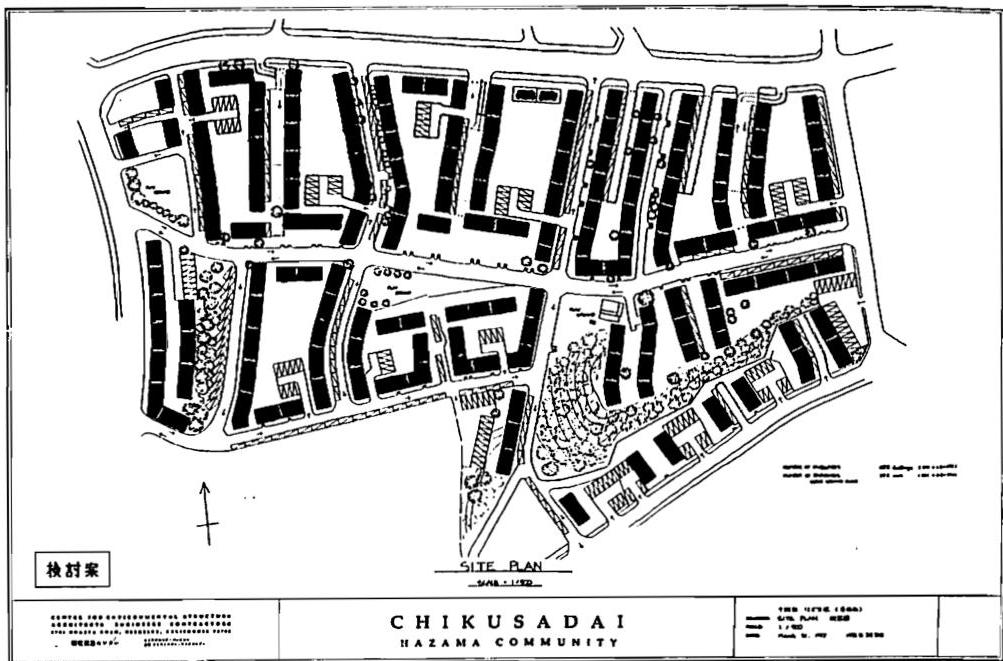

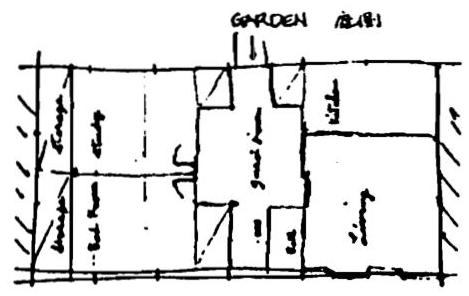

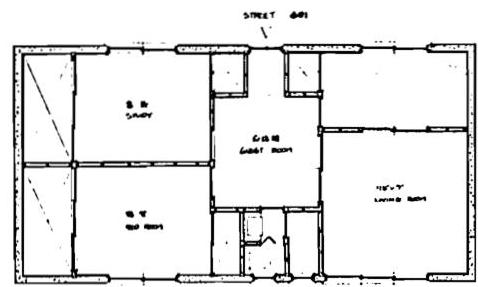

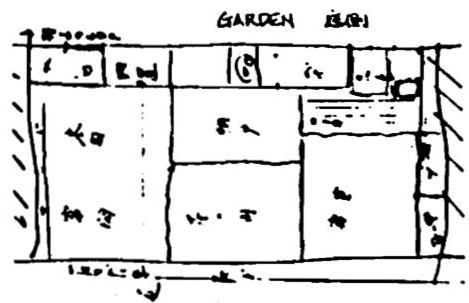

- HIGH-DENSITY HOUSING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 311

- NECESSARY FURTHER DYNAMICS OF ANY NEIGHBORHOOD WHICH COMES TO LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 333

PART FOUR

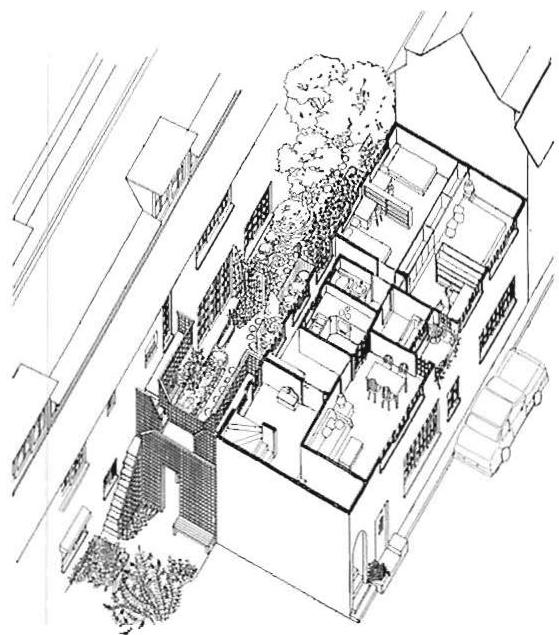

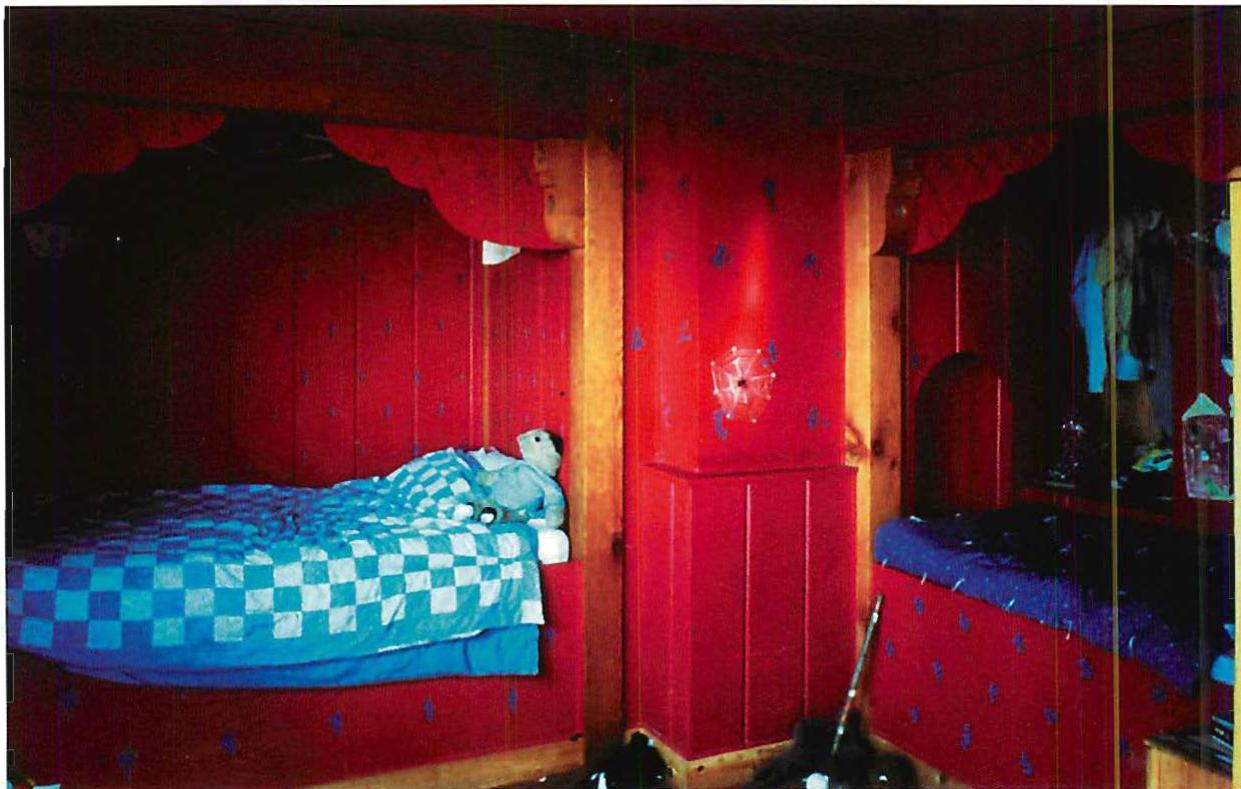

- THE UNIQUENESS OF PEOPLE’S INDIVIDUAL WORLDS . . . . . . 361

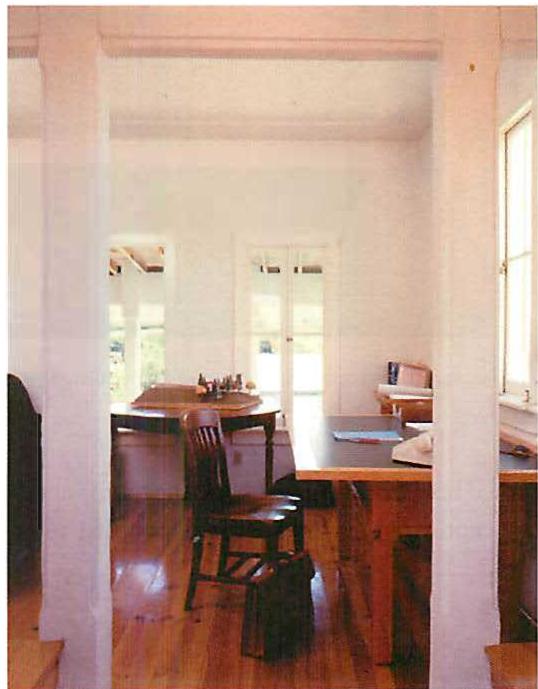

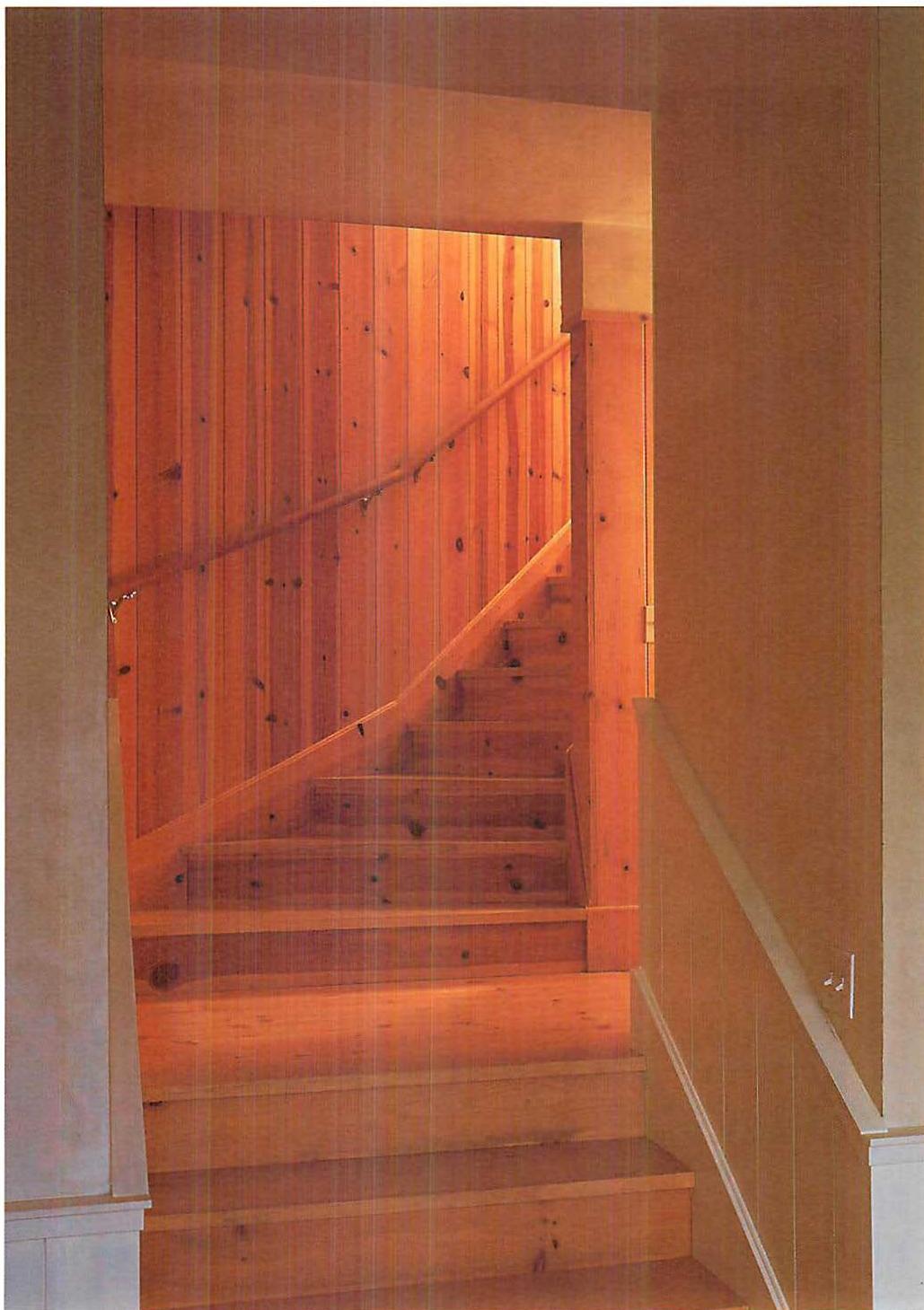

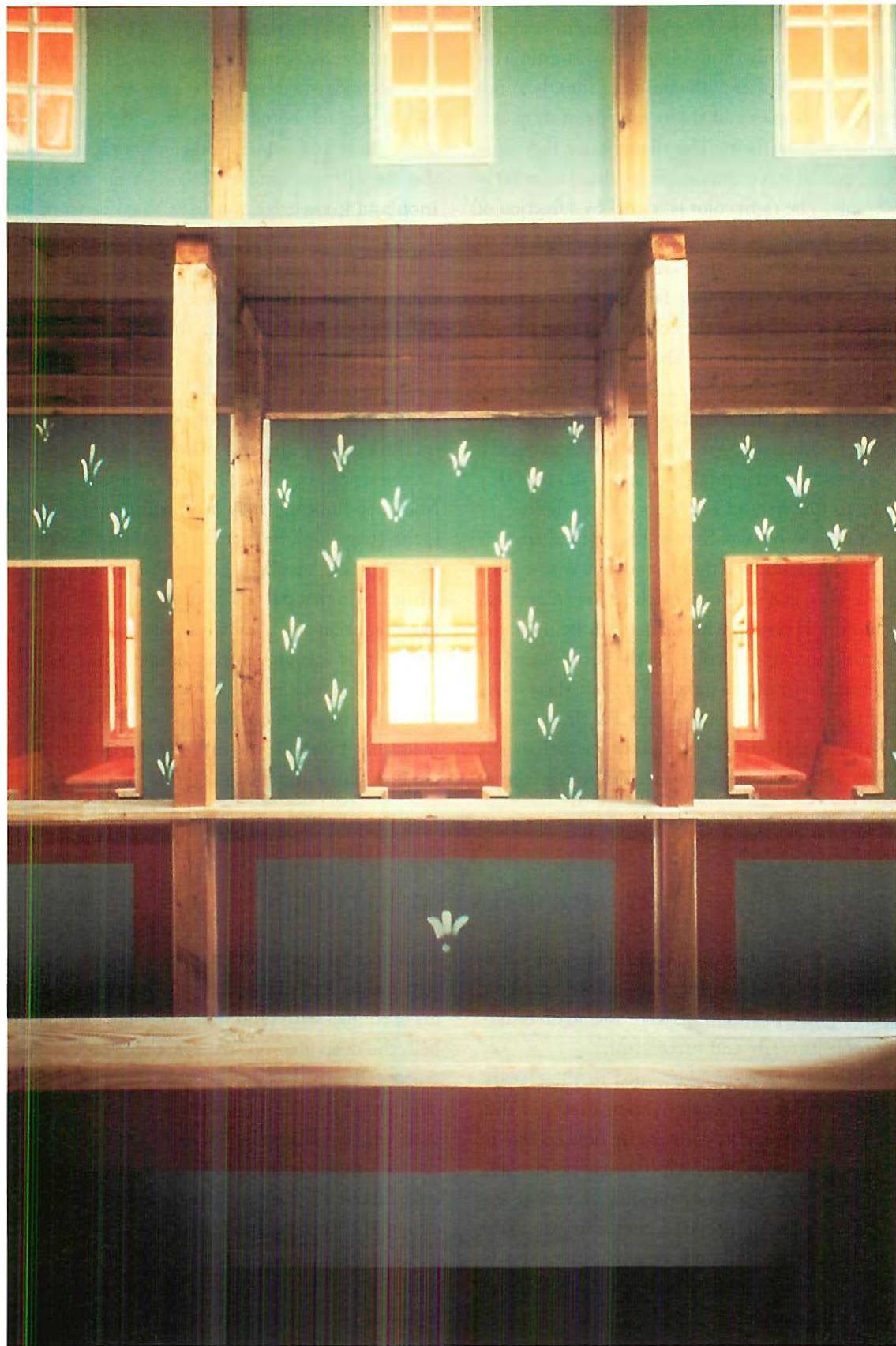

- THE CHARACTER OF ROOMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 411

PART FIVE

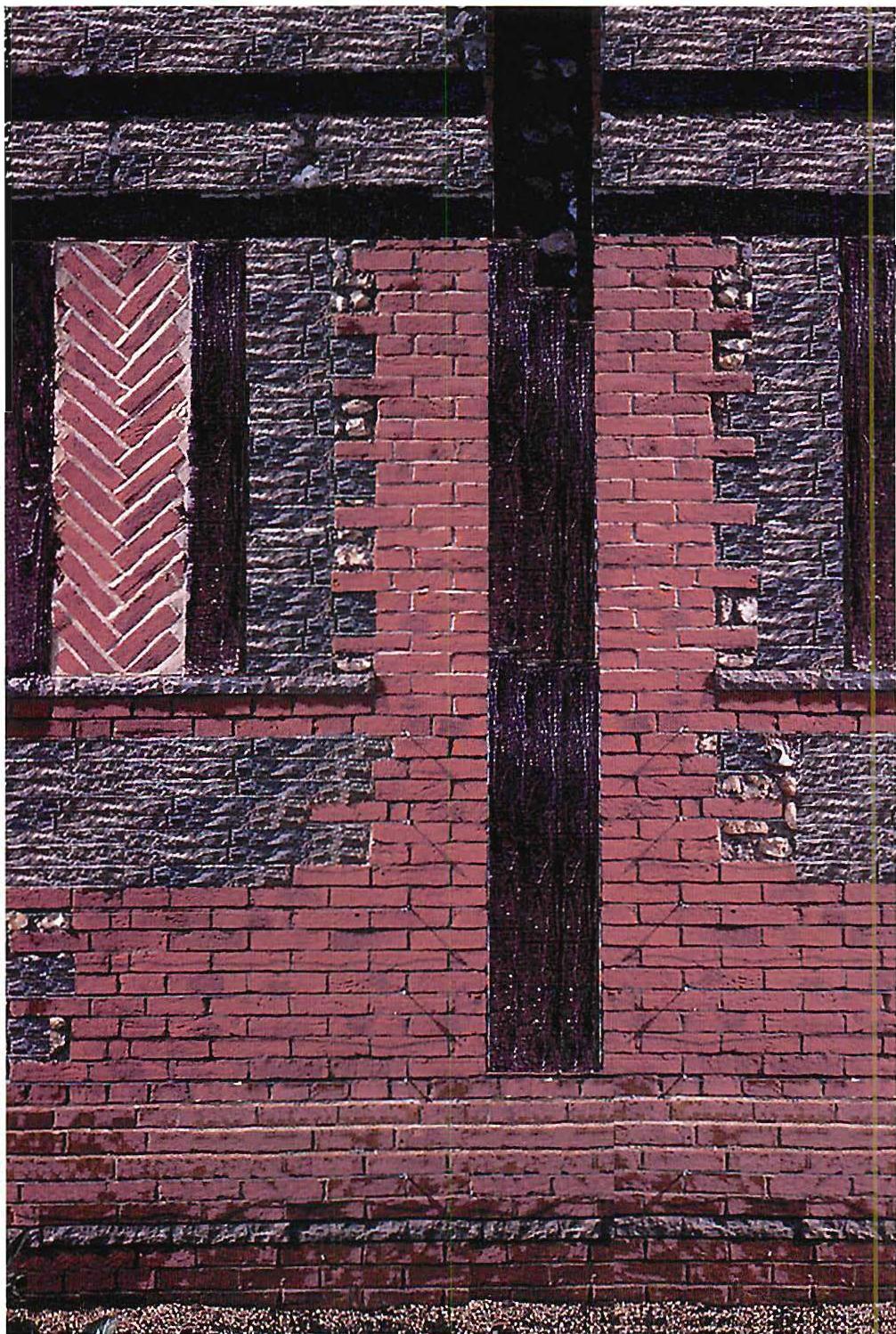

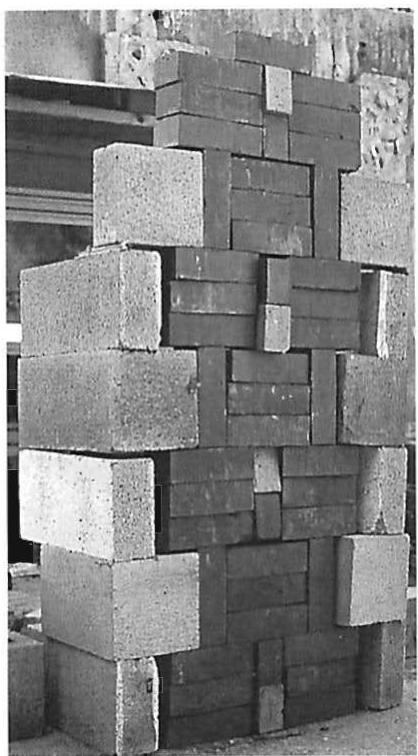

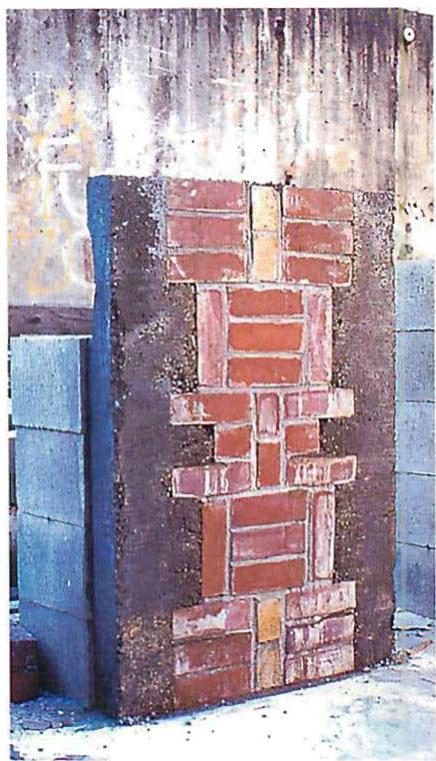

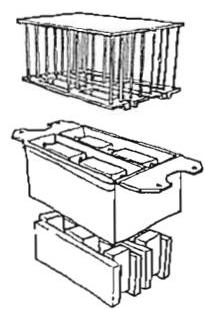

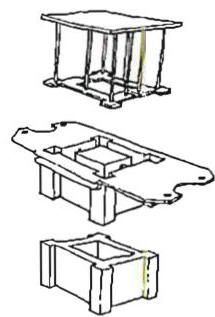

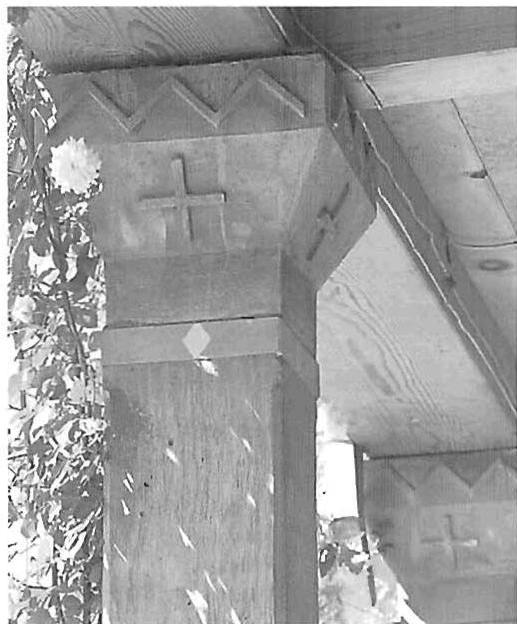

- CONSTRUCTION ELEMENTS AS LIVING CENTERS . . . . . . . . 447

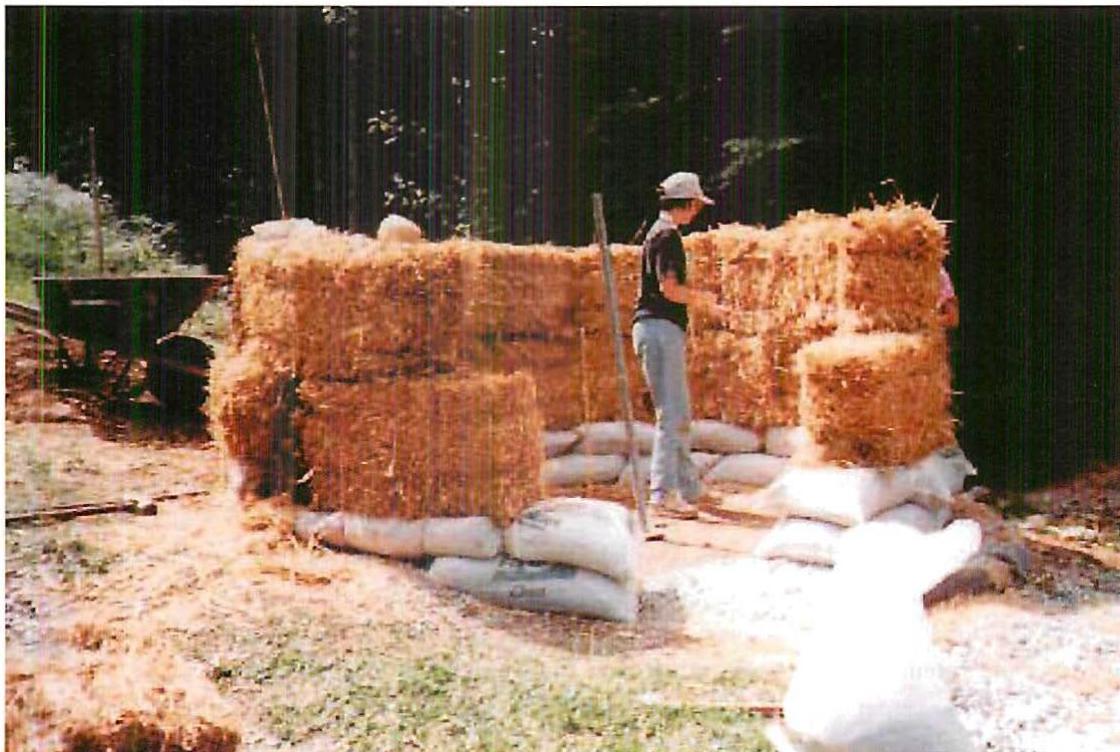

- ALL BUILDING AS MAKING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 481

- CONTINUOUS INVENTION OF NEW MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES . . 517

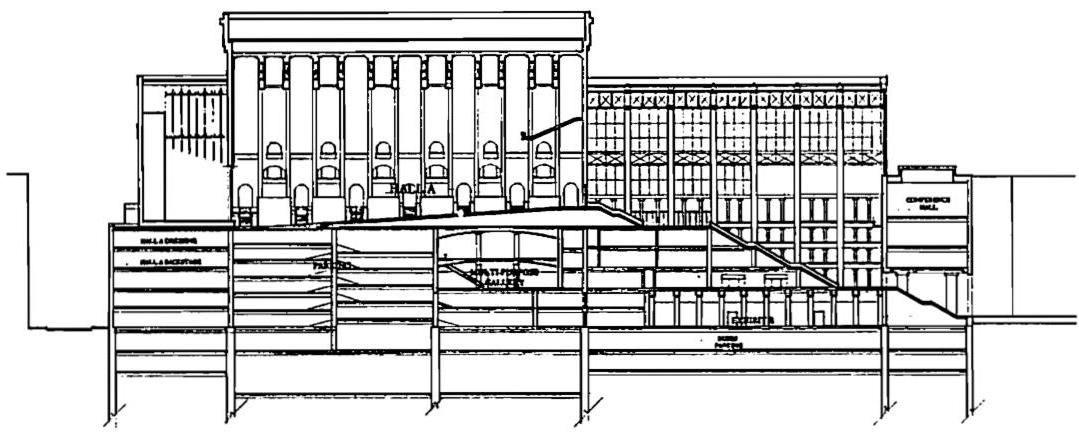

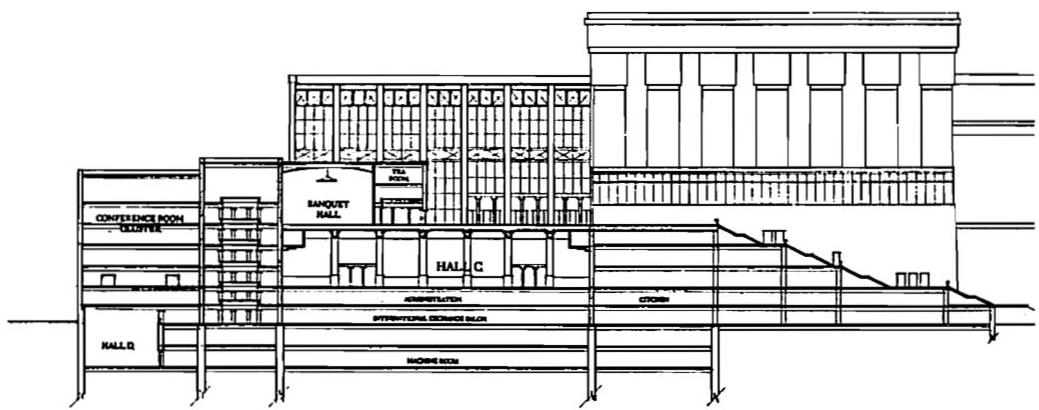

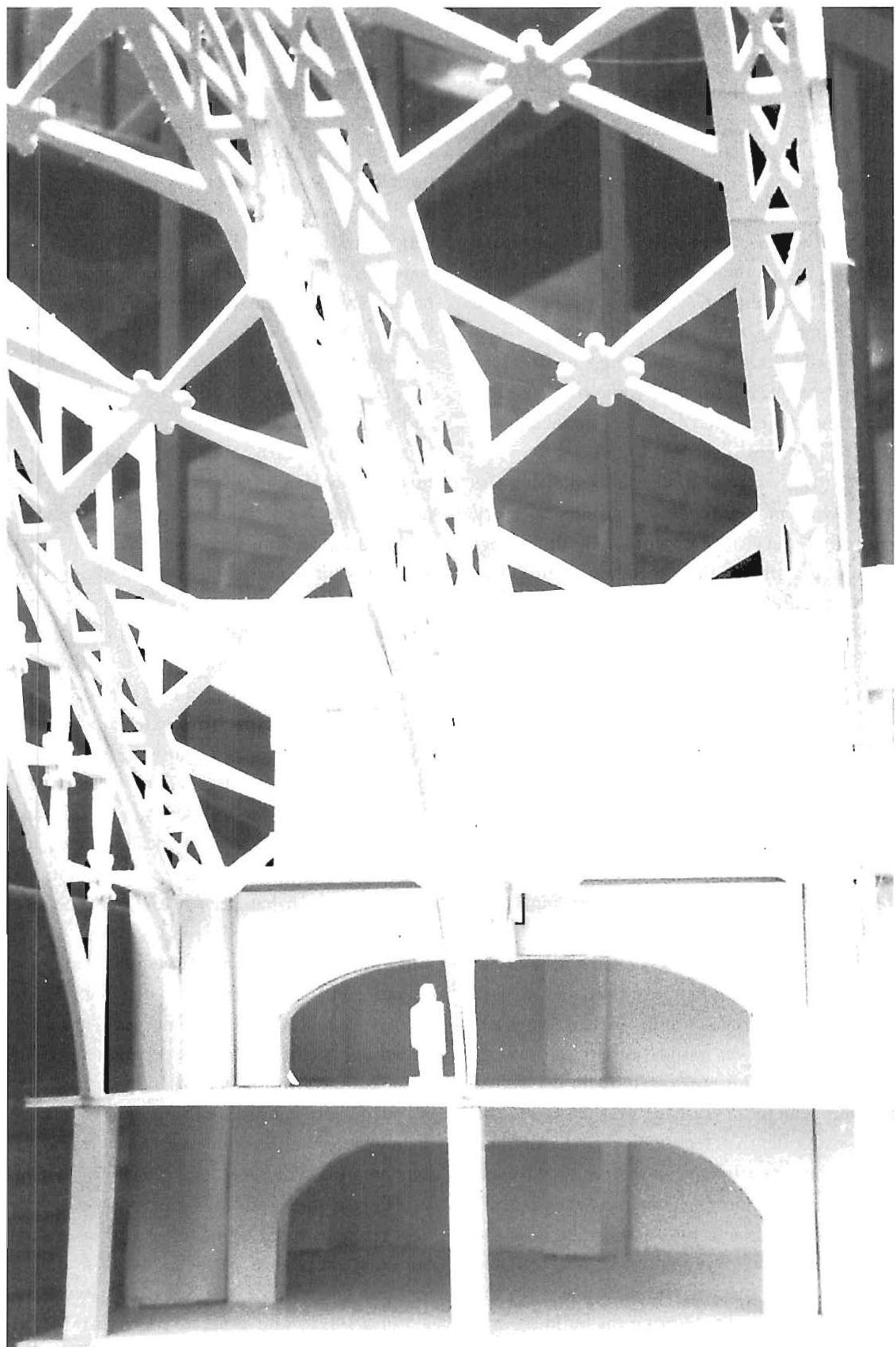

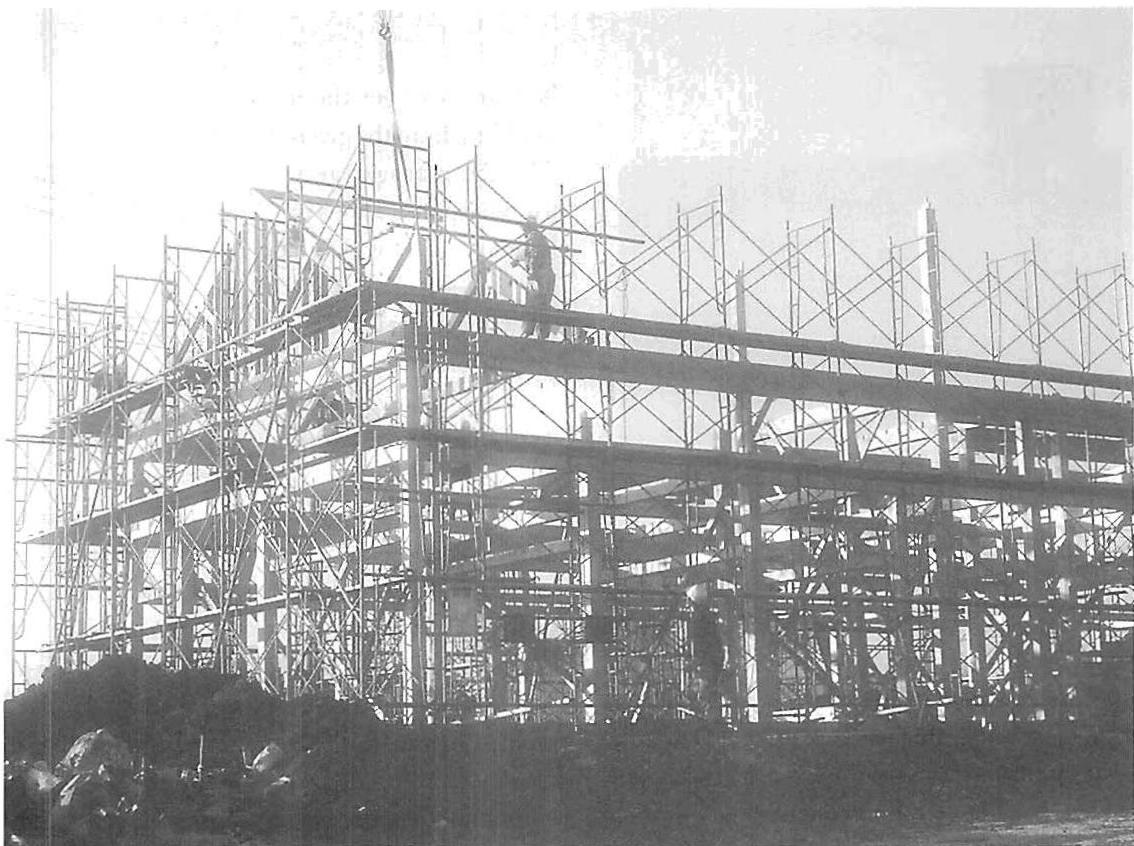

- PRODUCTION OF GIANT PROJECTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . 561

PART SIX

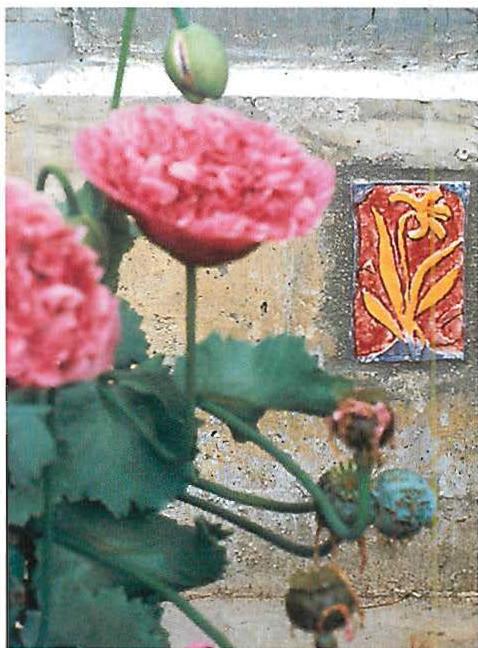

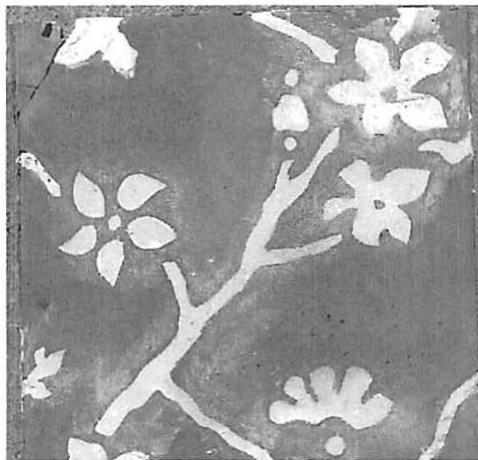

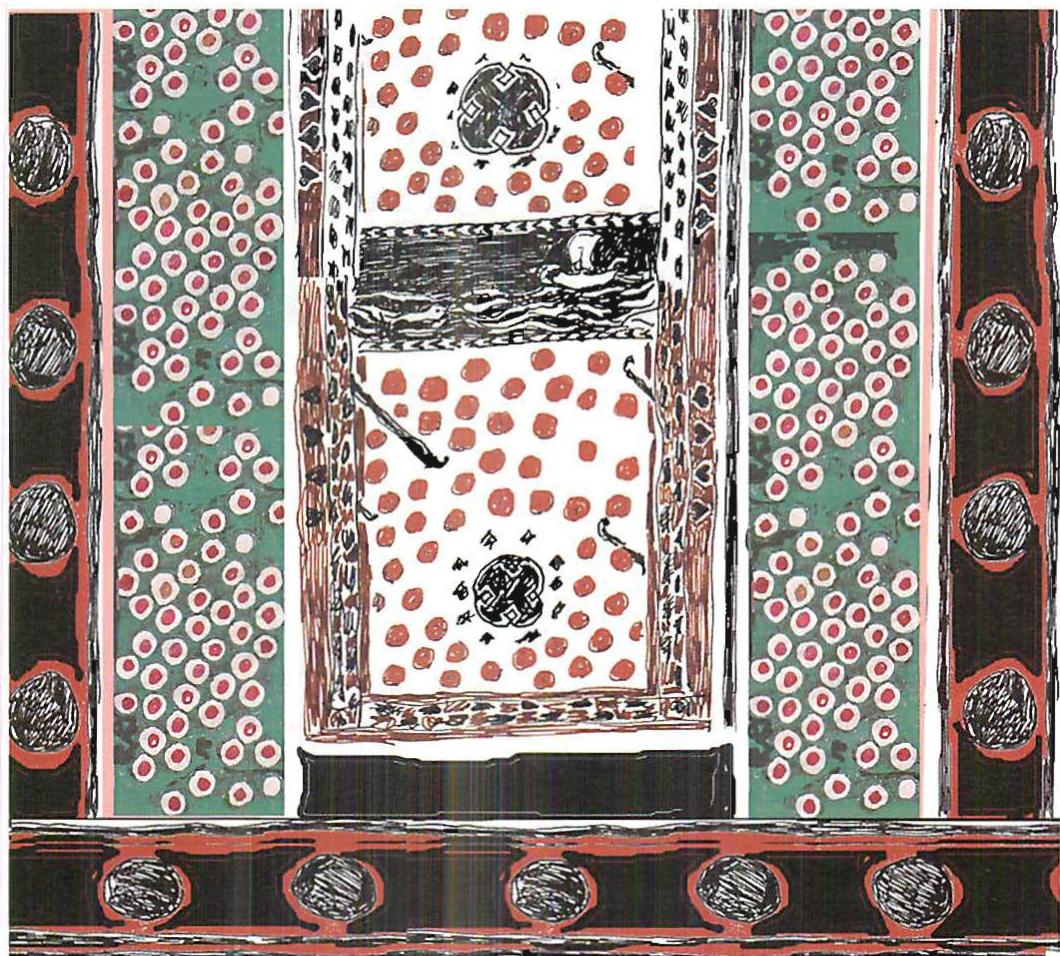

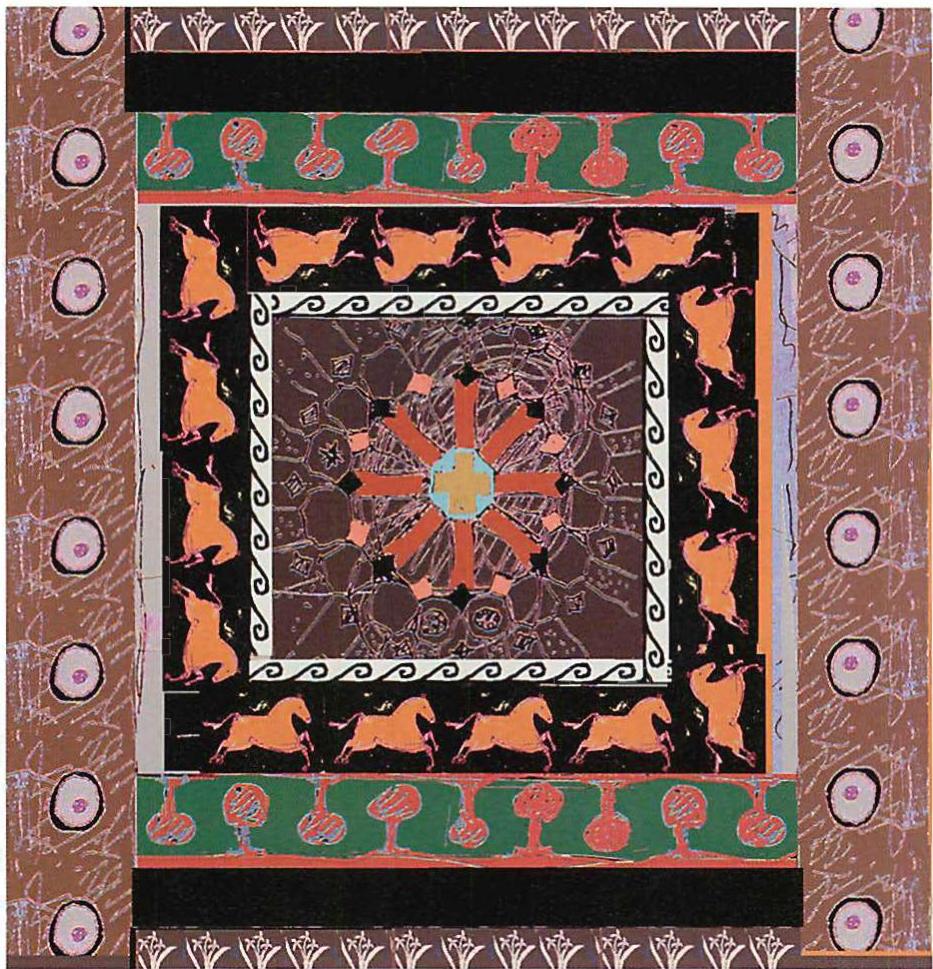

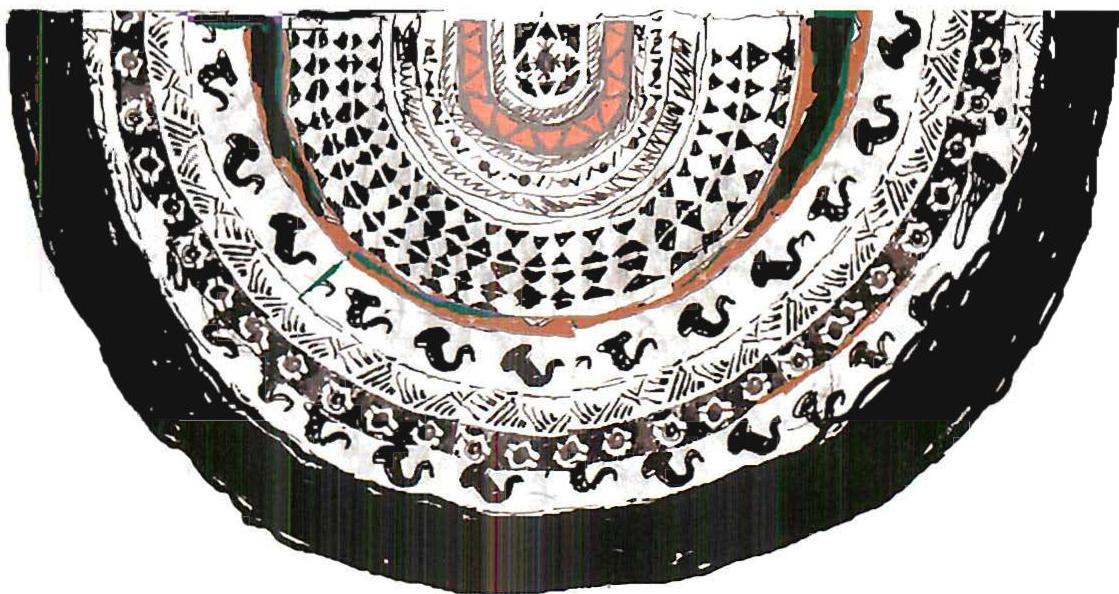

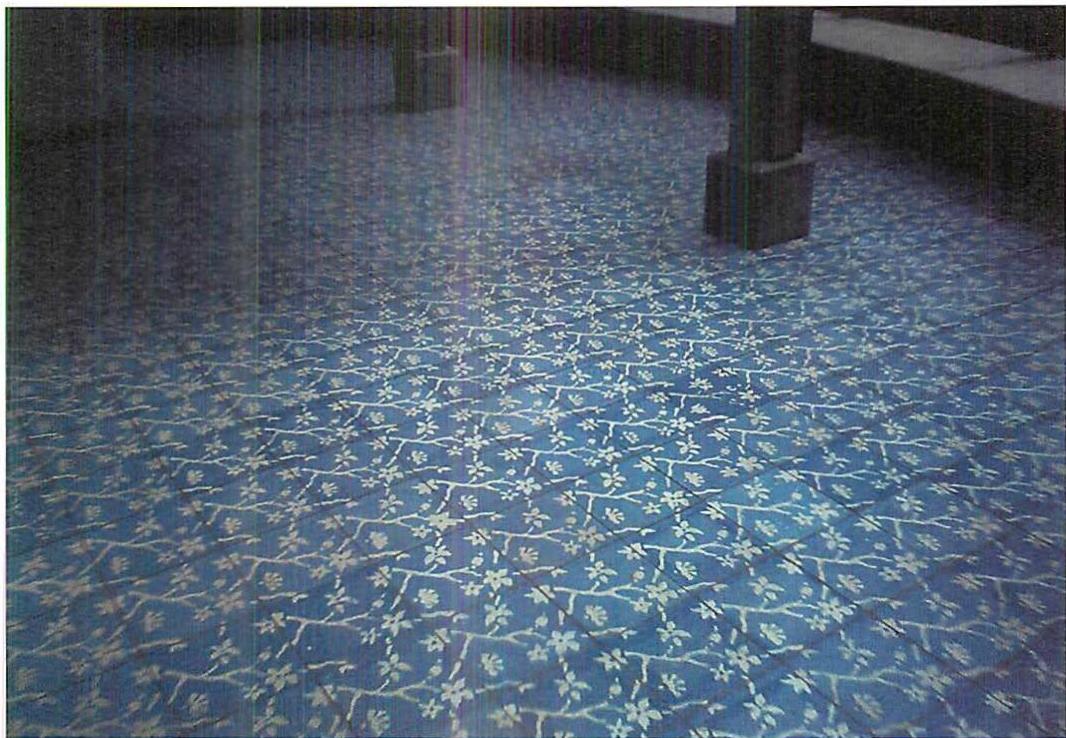

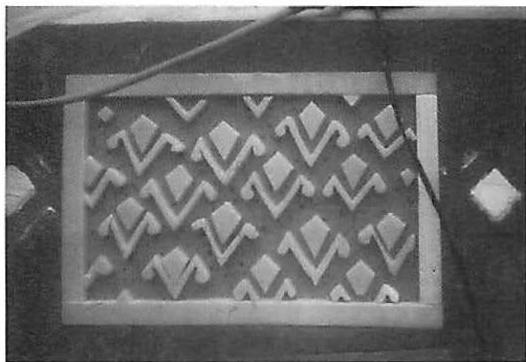

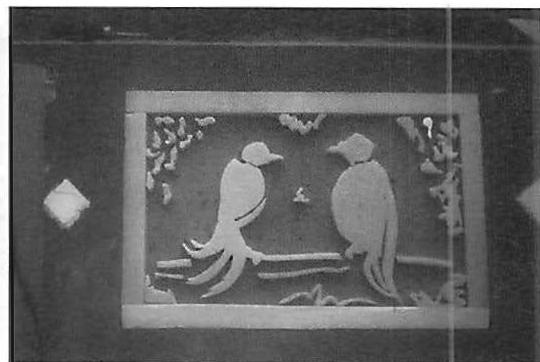

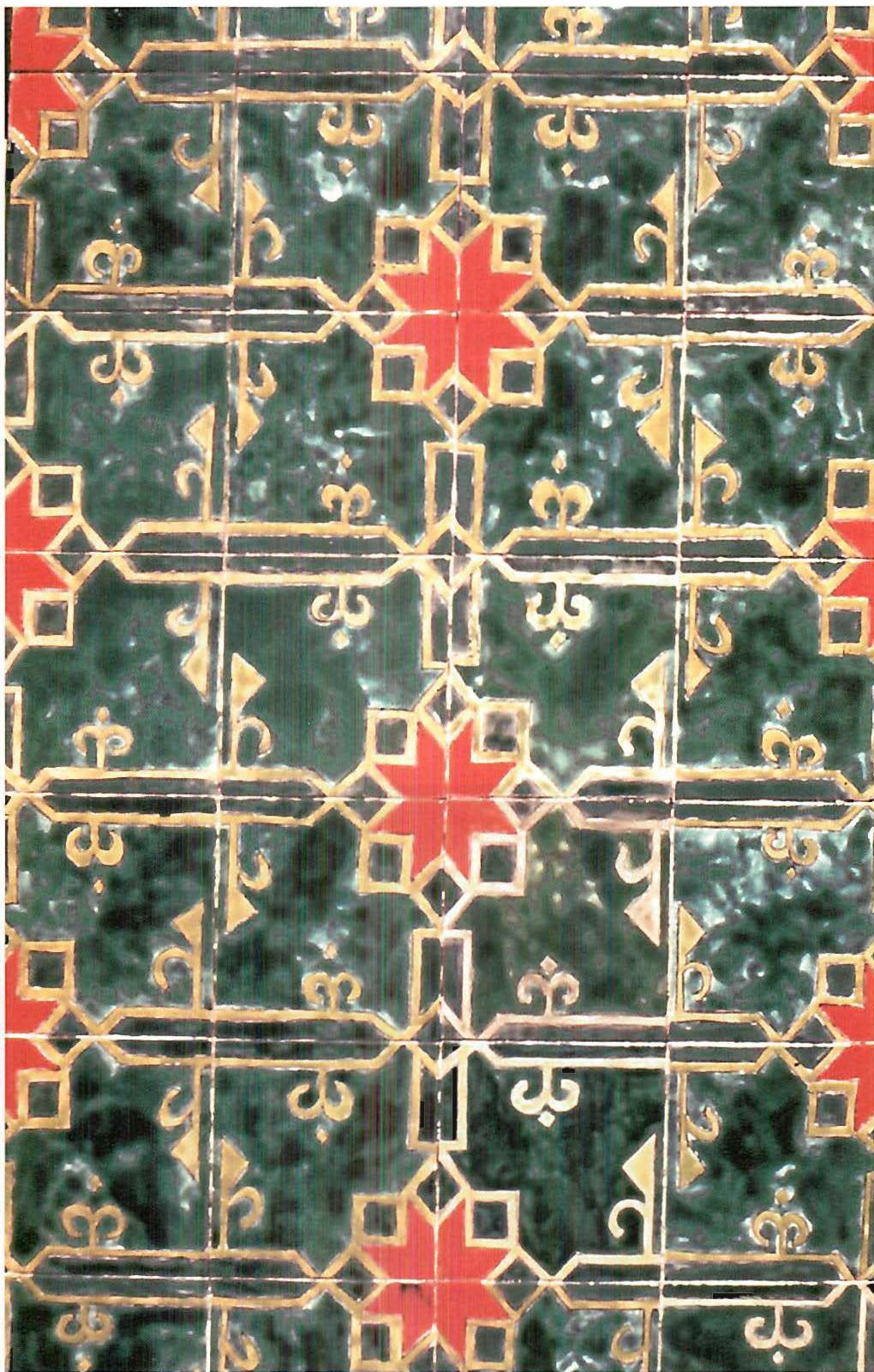

- ORNAMENT AS A PART OF ALL UNFOLDING . . . . . . . . . 579

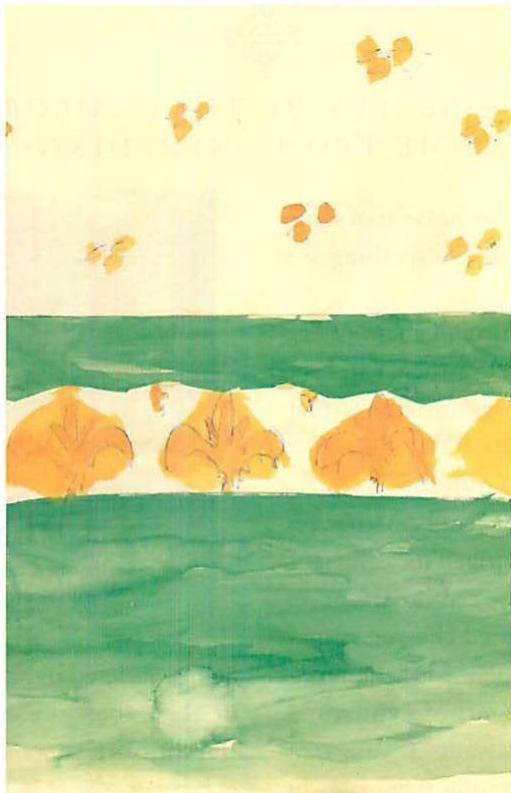

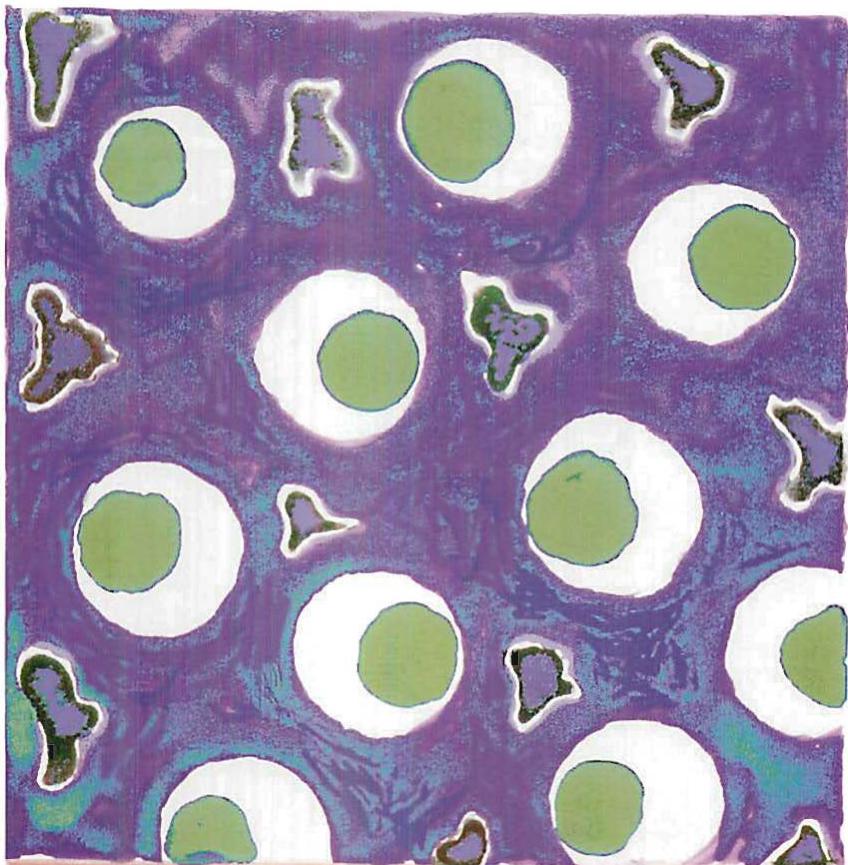

- COLOR WHICH UNFOLDS FROM THE CONFIGURATION . . . . . 615

PART SEVEN . . . . . . . . . 639

CONCLUSION: THE WORLD CREATED AND TRANSFORMED . . . . . 677 APPENDIX ON NUMBER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 685

BOOK FOUR: THE LUMINOUS GROUND

PREFACE: TOWARD A NEW CONCEPTION OF THE NATURE OF MATTER . . . I

PART ONE

- OUR PRESENT PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . . . . . . . 9

- CLUES FROM THE HISTORY OF ART . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

- THE EXISTENCE OF AN “I” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

- THE TEN-THOUSAND BEINGS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

- THE PRACTICAL MATTER OF FORGING A LIVING CENTER. . . . . III

MID-BOOK APPENDIX: RECAPITULATION OF THE ARGUMENT. . . . . 135

PART TWO

- THE BLAZING ONE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

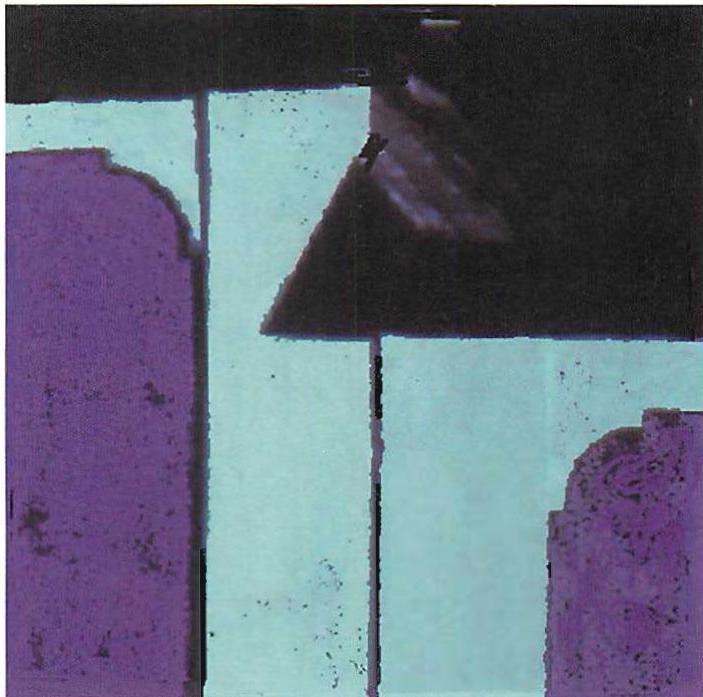

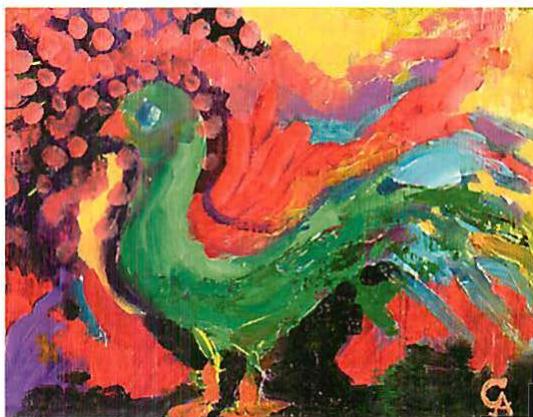

- COLOR AND INNER LIGHT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

- THE GOAL OF TEARS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

- MAKING WHOLENESS HEALS THE MAKER. . . . . . . . . . . 261

- PLEASING YOURSELF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271

- THE FACE OF GOD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 301

CONCLUSION TO BOOKS 1-4

A MODIFIED PICTURE OF THE UNIVERSE . . . . . . . . . . . 317 EPILOGUE: EMPIRICAL CERTAINTY AND ENDURING DOUBT . . . . 339 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 345

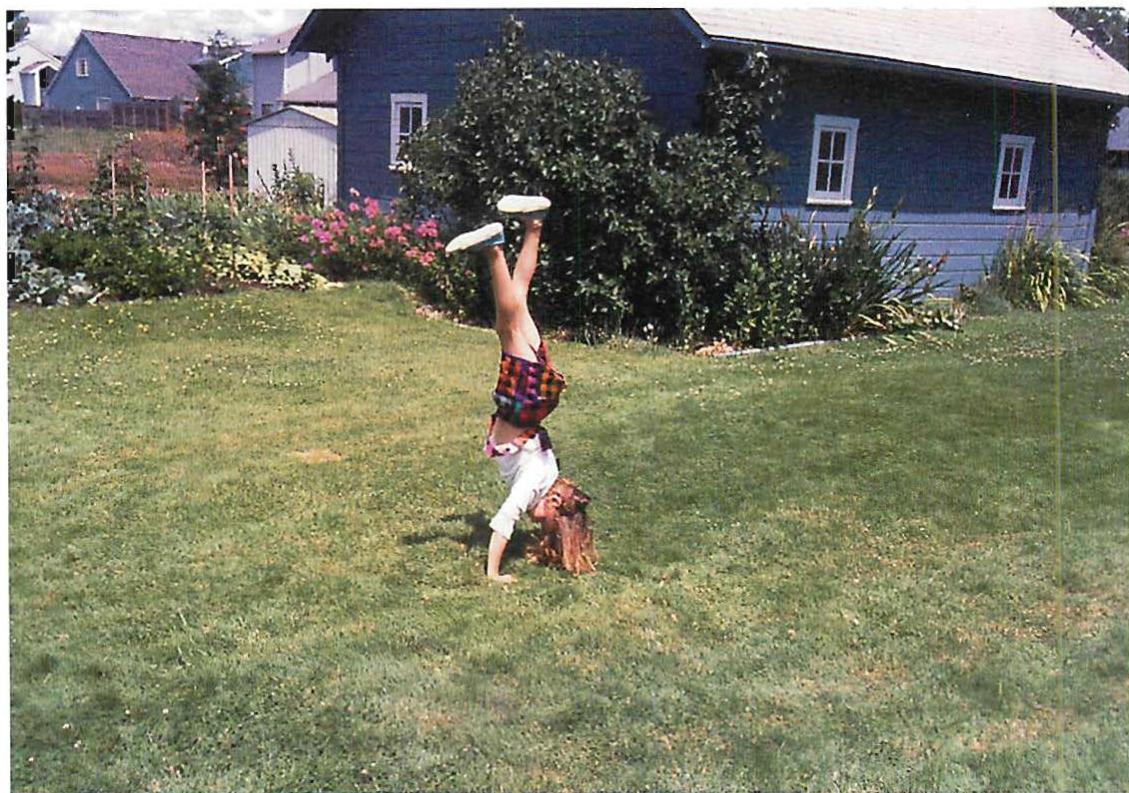

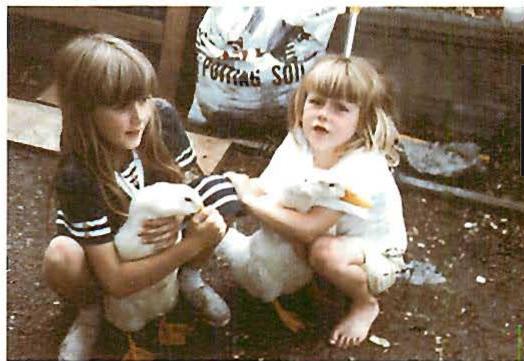

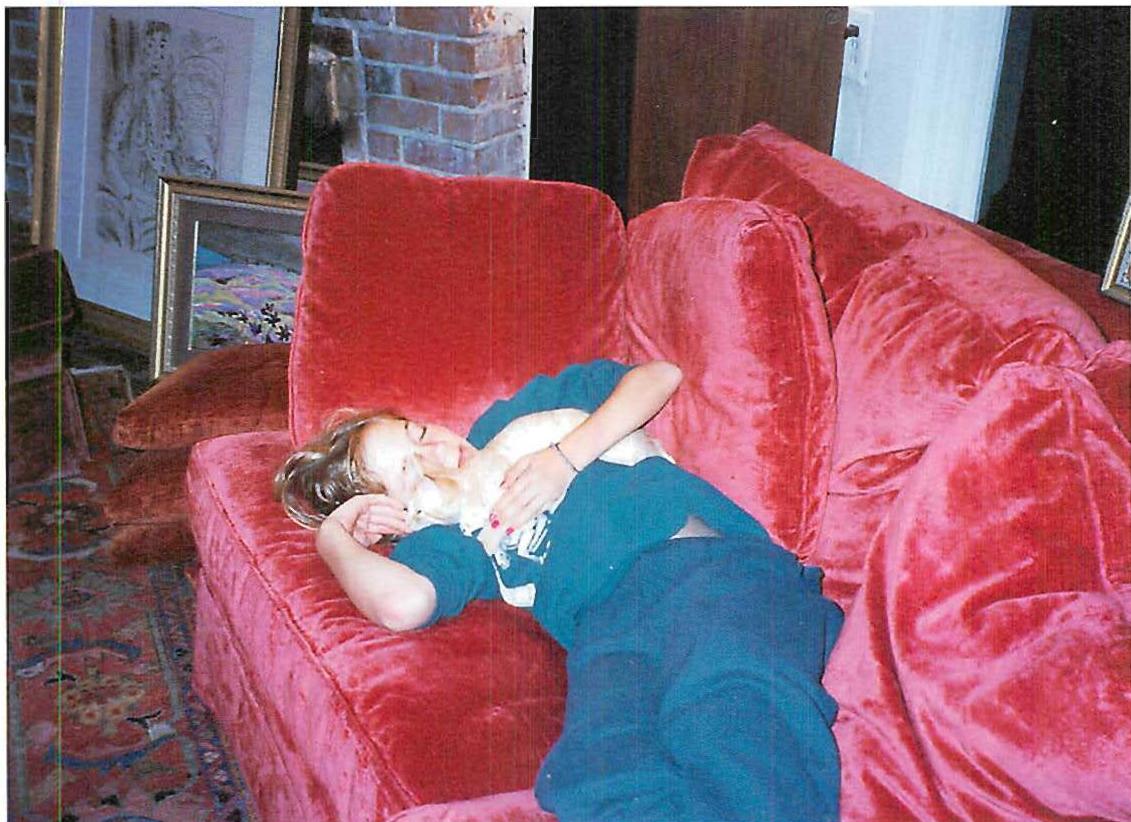

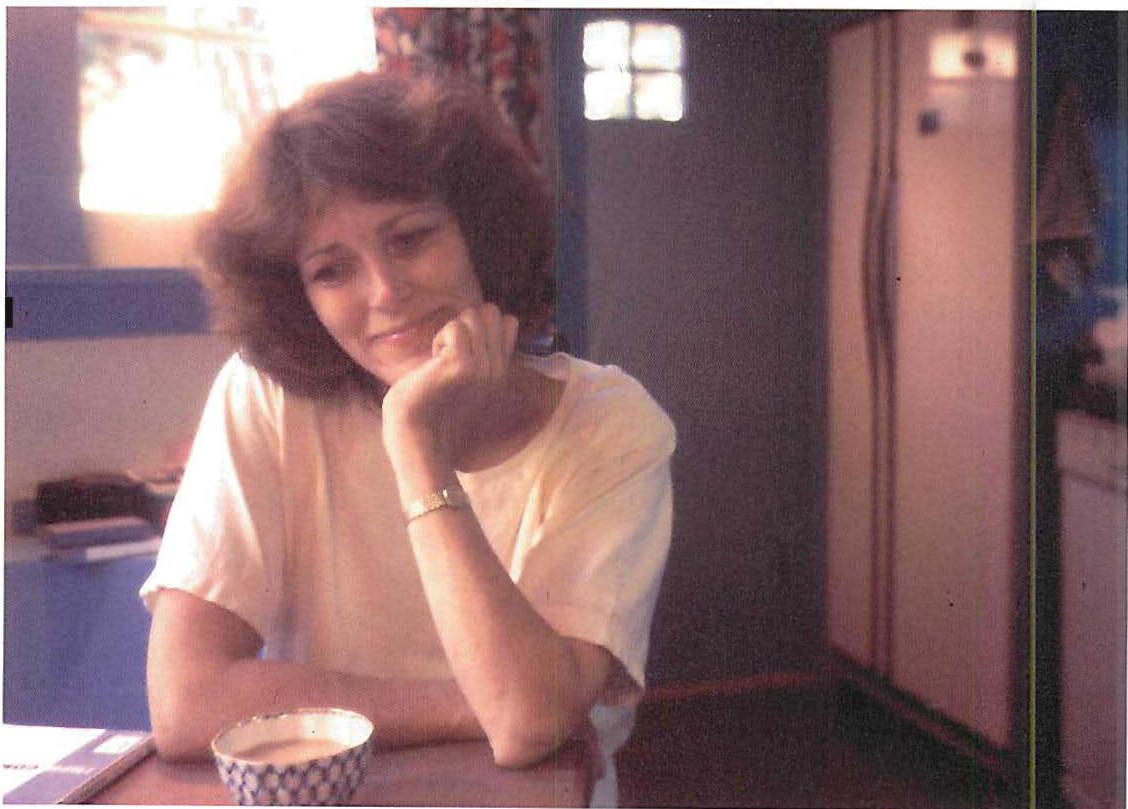

I DEDICATE THESE FOUR BOOKS TO MY FAMILY:

TO MY BELOVED MOTHER, WHO DIED MANY YEARS AGO;

TO MY DEAR FATHER, WHO HAS ALWAYS HELPED ME AND INSPIRED ME;

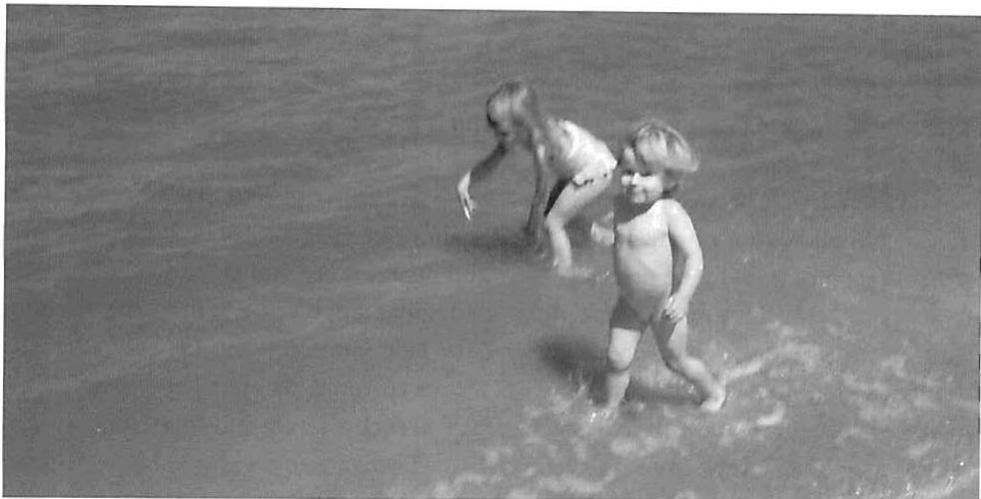

TO MY DARLINGS LILY AND SOPHIE;

AND TO MY DEAR WIFE PAMELA WHO GAVE THEM TO ME,

AND WHO SHARES THEM WITH ME.

THESE BOOKS ARE A SUMMARY OF WHAT I HAVE UNDERSTOOD ABOUT

THE WORLD IN THE SIXTY-THIRD YEAR OF MY LIFE.

A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD

PREFACE

LIVING PROCESSES REPEATED TEN MILLION TIMES

1 / MY INTENTION IN BOOK 3

In Book 1, THE PHENOMENON OF LIFE, I have offered a view of the natural and built worlds in which order is seen as underlying all life, and life—visible as living structure—a common and necessary feature of buildings.

In Book 2, THE PROCESS OF CREATING LIFE, I have argued that it is a special kind of adaptive process, not a mechanical or arbitrary application of properties, that creates life. Life in nature, and in the humanly constructed world, is generated by a process of unfolding in which living structure grows in stepwise fashion from a current condition (the system of centers which exists) and takes on greater life by a series of structure-preserving transformations, or adaptations. This life-generating process is, I have argued, knowable and can guide human actions. The process is inherent in nature's infinite complexity and can only be grasped to a first approximation, but my hope is that readers will entertain and use the conception of living process as a reasonable approximation of how the built world comes to life.

Throughout Books 1 and 2, I have not disguised my belief and anger that the modern world—especially with the advent of professional architecture separated from building—has lost touch with life in the world we are making. We live in a world degraded and overwhelmed by construction which is driven by forces very different from, and often oblivious to, what I have been describing as necessary conditions for creating living order.

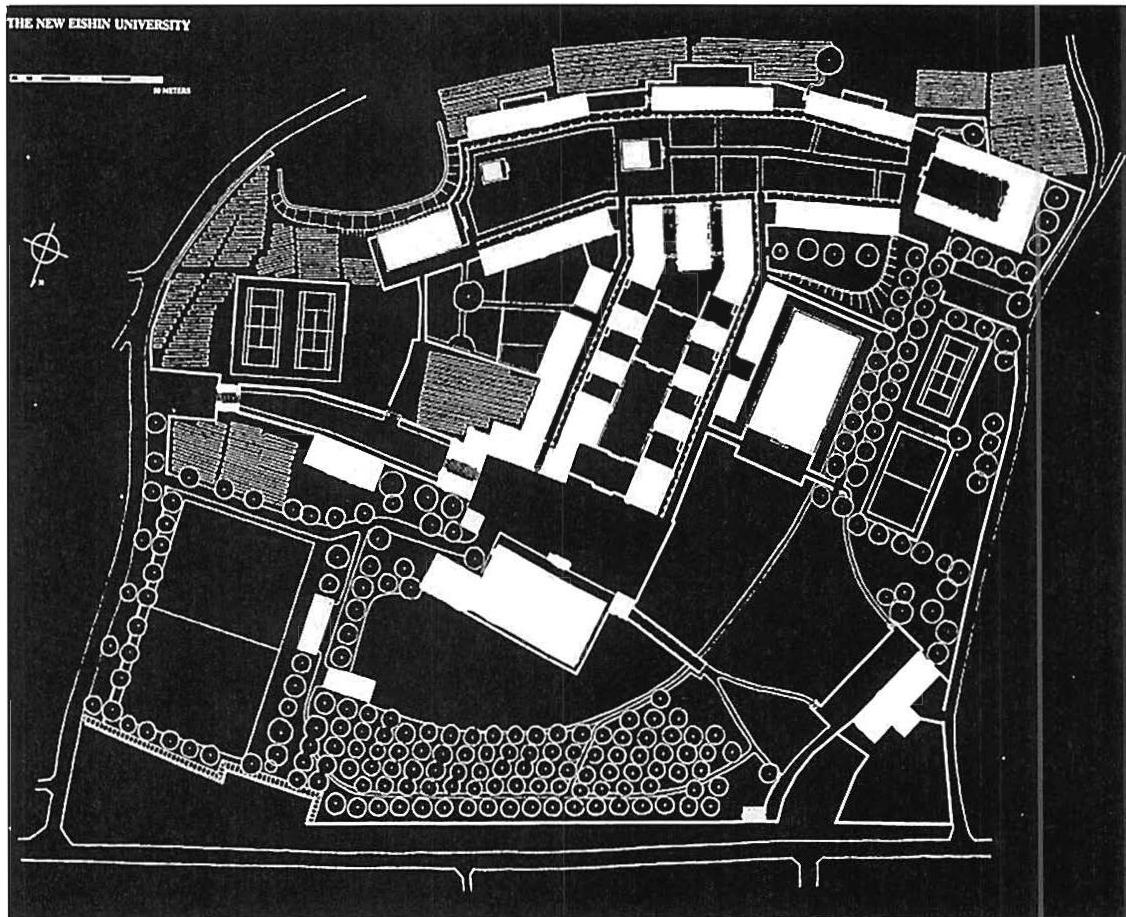

In this book, A VISION OF A LIVING WORLD, I try to show what happens if living processes are used pervasively, in widespread fashion, in our own era, and what kind of overall environment we may expect to see from their effects. I show examples of large buildings, small buildings, neighborhoods, gardens, public space, wilderness, houses, construction details, color, ornament. Above all, I try to show what

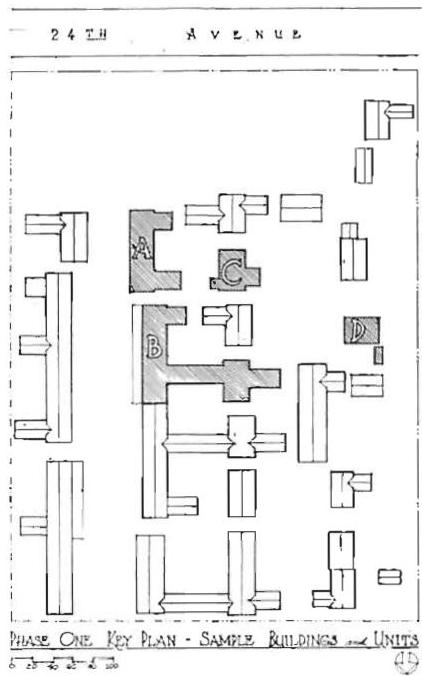

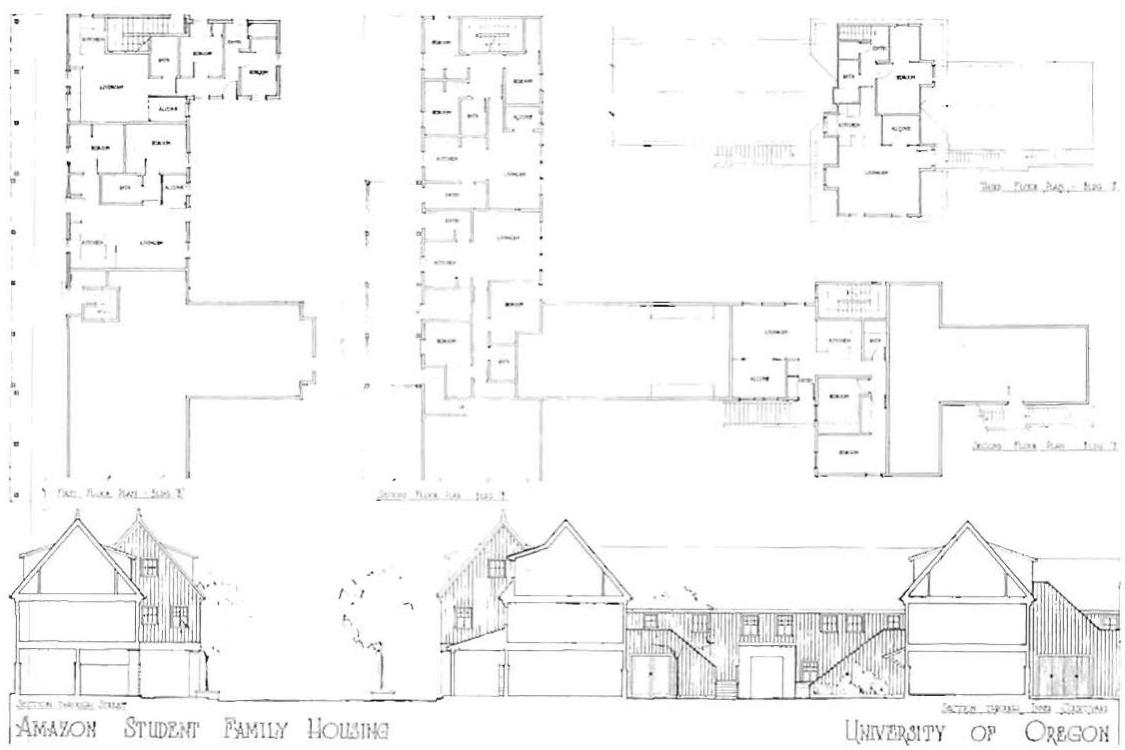

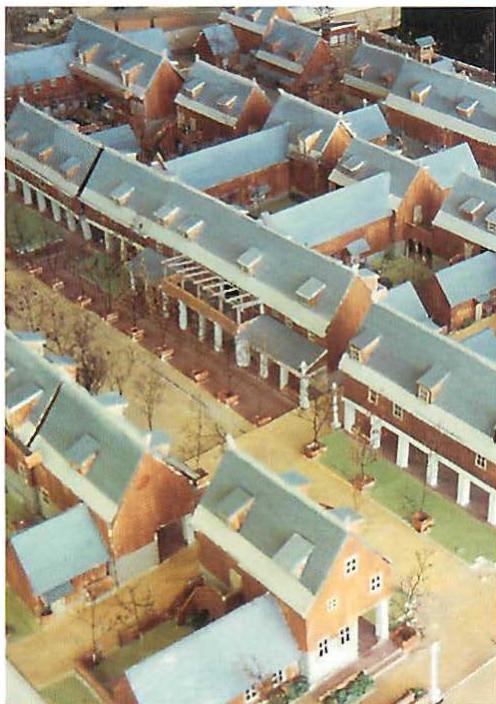

is likely to happen in the large: to show the likely impact on the whole. To build this overall picture, I have used hundreds of examples of buildings, plans, designs, which my colleagues and I have made, supplemented by buildings made by others which seem to derive from similar insights. The examples draw from a large body of ideas and strategies for building which I have been able to develop with many colleagues at the Center for Environmental Structure in Berkeley, California (the Institute which, for the last thirty years, has served as my construction company and my architectural office), and with generations of graduate students in the Department of Architecture at the University of California.

It must be acknowledged that my generous opportunities to publish eight books on these matters with Oxford University Press, to work at the University of California for thirty-five years while working these things through, and to plan and build many real projects in different parts of the world, have not been without opposition and conflict. The views I am advocating on building process are not now widely accepted and they are often at odds with current ways of doing things. Still, I can only be grateful for having had so long and wide-ranging a chance to develop and to try many of my ideas on how to construct a wholesome, life-supporting world around us.

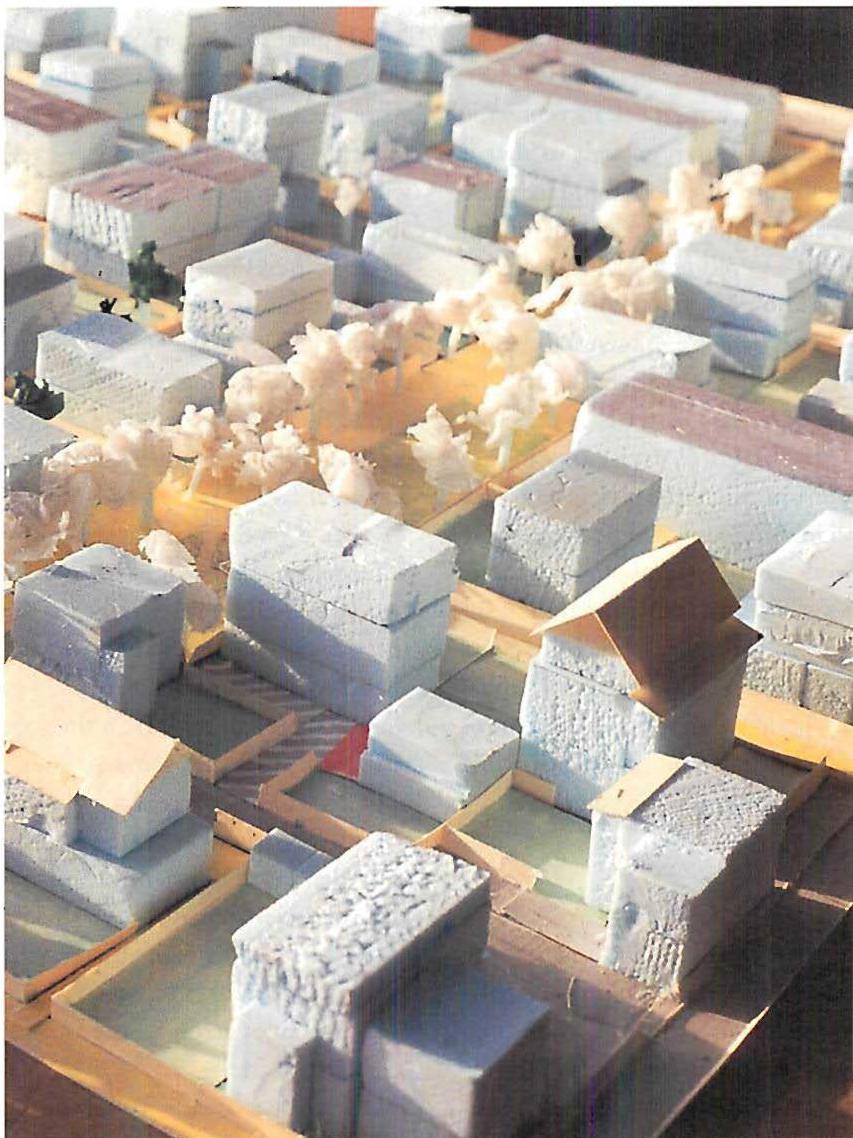

From the experiments and construction projects I have done over the last thirty years—all based, in some degree, on the concept of living process—I have accumulated enough projects to put them together in a way that forms a partial vision of a possible world for our time, as it would be generated by living processes. What is portrayed here, the vision portrayed, is the start of a vision of the kind of world we are likely to get from living processes if we use them today and tomorrow.

I hope to show that this world, because it is generated by repeated application of living processes, is indeed “living.” That means, in particular, I hope it is visible in my examples that such a world is nourishing to human life and to human feeling; that it encompasses what we need, our joys, our sorrows. I would like you to begin to feel, for yourself, that such a world may be (at least in part) a model of the kind of world in which we might wish to live and in which we can live well.

I also mean to construct a picture which is at least partly independent of our era. Although the particular world I show is set in the 20th and 21st centuries, and deals with our immediate world and our immediate society, I mean to portray this world in such a way that some version of the same thing will in all likelihood be valid and relevant in any future period of history, thus equally appropriate (in some future version) to the 24th century or to the 30th century.

I am trying to show that no matter what the world is like, no matter what its style is, no matter its immediate technical character — still, if it is truly generated by adaptation as I define it, then in a deep sense, in one form or another, it will — it must — look something like what I am showing here — if it truly is a living structure. Of course the technology must change — the building materials — and the social habits and culture, those will probably all change, too — but I mean to construct a picture which displays certain ultimate structural invariants — a broad general character that must, within a margin of error, anyway, be present in all worlds made appropriate to the inner life of human beings. And I mean to display this all so concretely that we can at least begin to see how we might build this world on a larger scale, today, tomorrow, and in the future.

You could argue that the contents of Book 3 represent an idiosyncratic personal vision of what a living world might be. But it is not just a personal vision. I believe that what is demonstrated here, what is visible here, are — sui generis — the kinds of places which must inevitably arise whenever living processes are used, by anyone or everyone, to get living structure in the world.

If I am right about this, the personal aspect of what I have done should fade away in comparison to the importance of this material as a demonstration of what living structure, generated by ultra-modern methods, will look like. That is what I hope to have done. If I am right that living structure is a knowable thing, and that the living processes defined in Book 2 are the way to achieve it, this Book 3 should show, by illustration, what such a living world might be like.

Throughout, my intent is not to show a style or a particular way of designing things. It is to show what will happen if we use living processes repeatedly to generate living structure in the world, and what it might be like if this living structure is nearly all that is created.

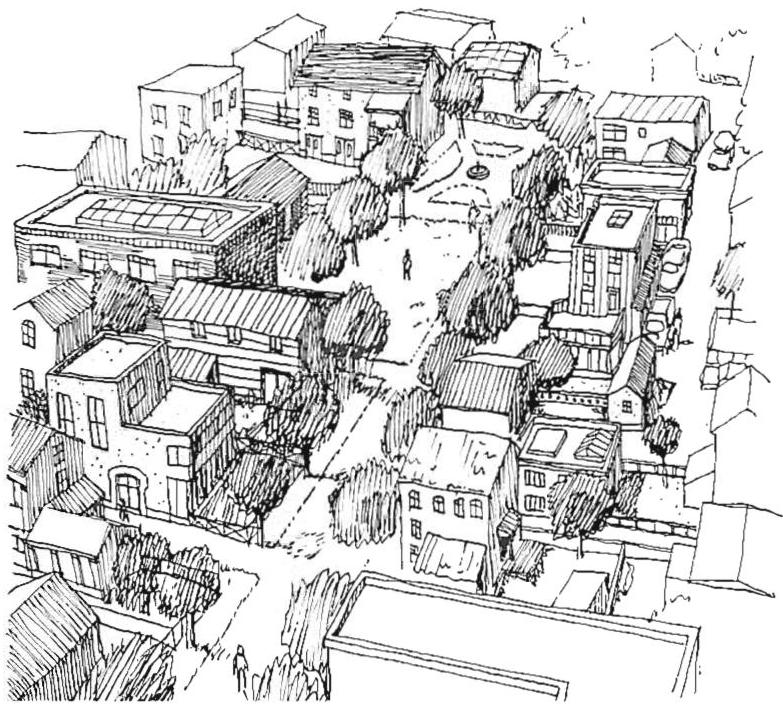

2 / REPEATED APPLICATION OF LIVING PROCESS IN CITY AND IN COUNTRYSIDE

I propose, then, that the world should be created by adaptive processes which act as nature does, itself. They allow us to create a harmonious whole that embraces nature and creates buildings, streets, and towns, in a fashion which has the same deep structure as nature, and has the same deep effect on us as a result. This, I believe, is how true life in our world has always been formed and must be formed. It is not something I have invented; I am only calling attention to it and trying to suggest that we who build the world must do our work within this framework.

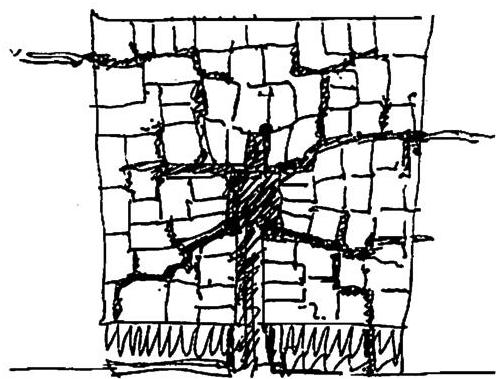

In such a process the land — the Earth — is to be enhanced continuously by adaptive steps that develop and increase its harmony. Gradually, daily, carefully, step by step, the built world

is to be created and recreated constantly in a way that millions of people take part in it. Each process adds one tiny bit of structure, deepens the structure. Each building comes into being as an extension of the land. Each house and street and fence and stair rail becomes a harmonious extension of the land. Each part of every building, too, becomes an enhancement of the town in which it sits, an enhancement of its street and neighborhood. New centers appear thousand-fold each day, and each center that is added increases and deepens harmony.

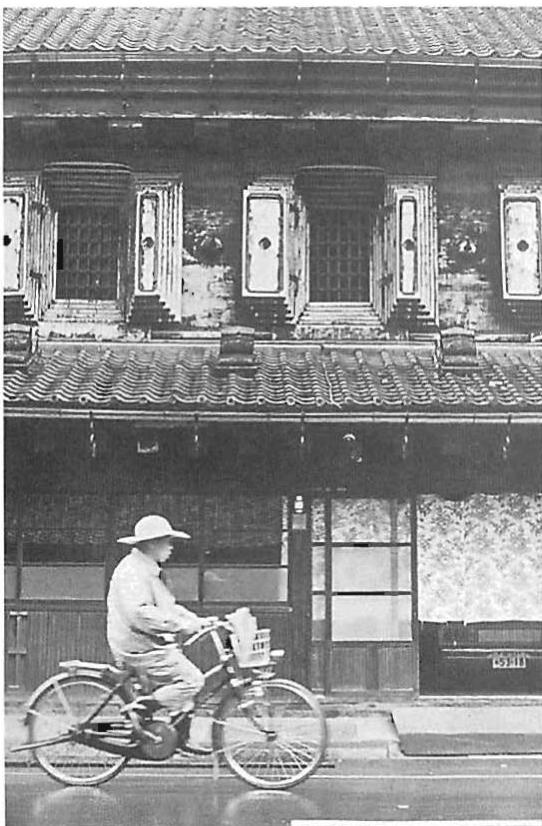

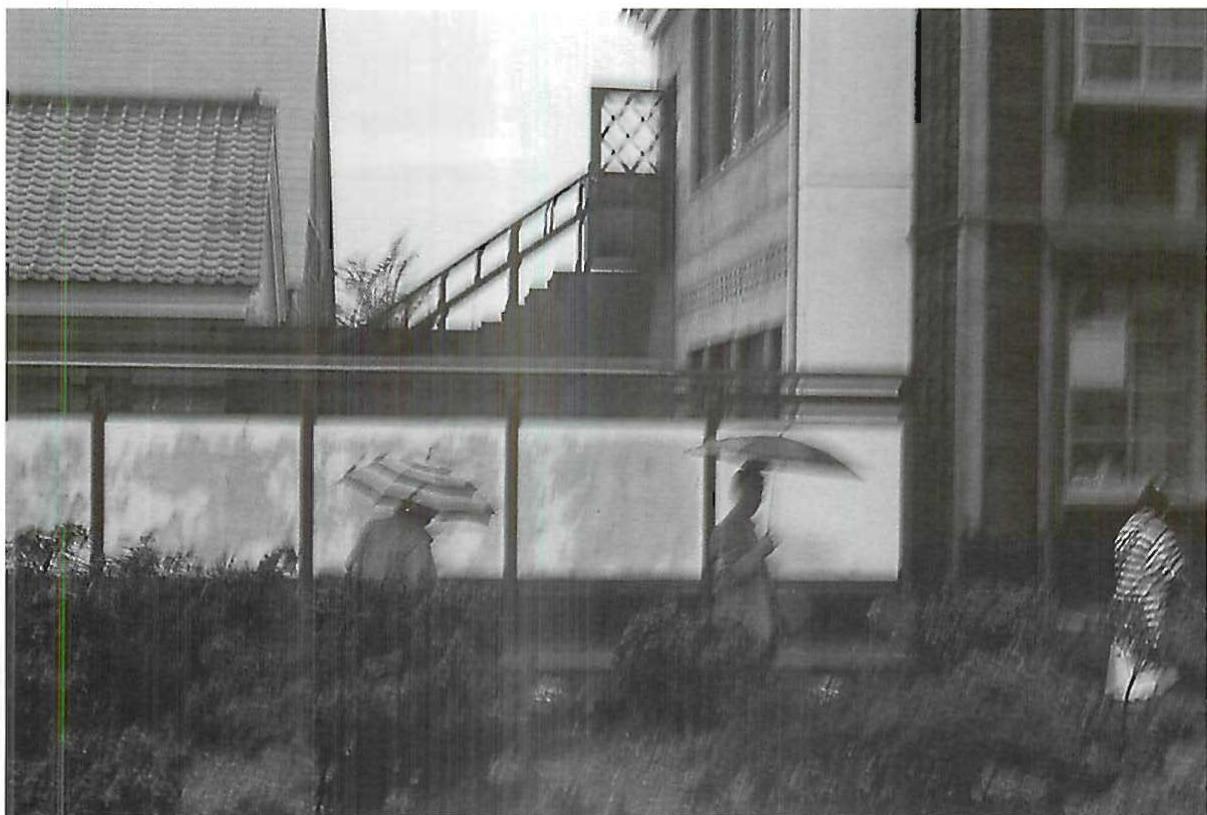

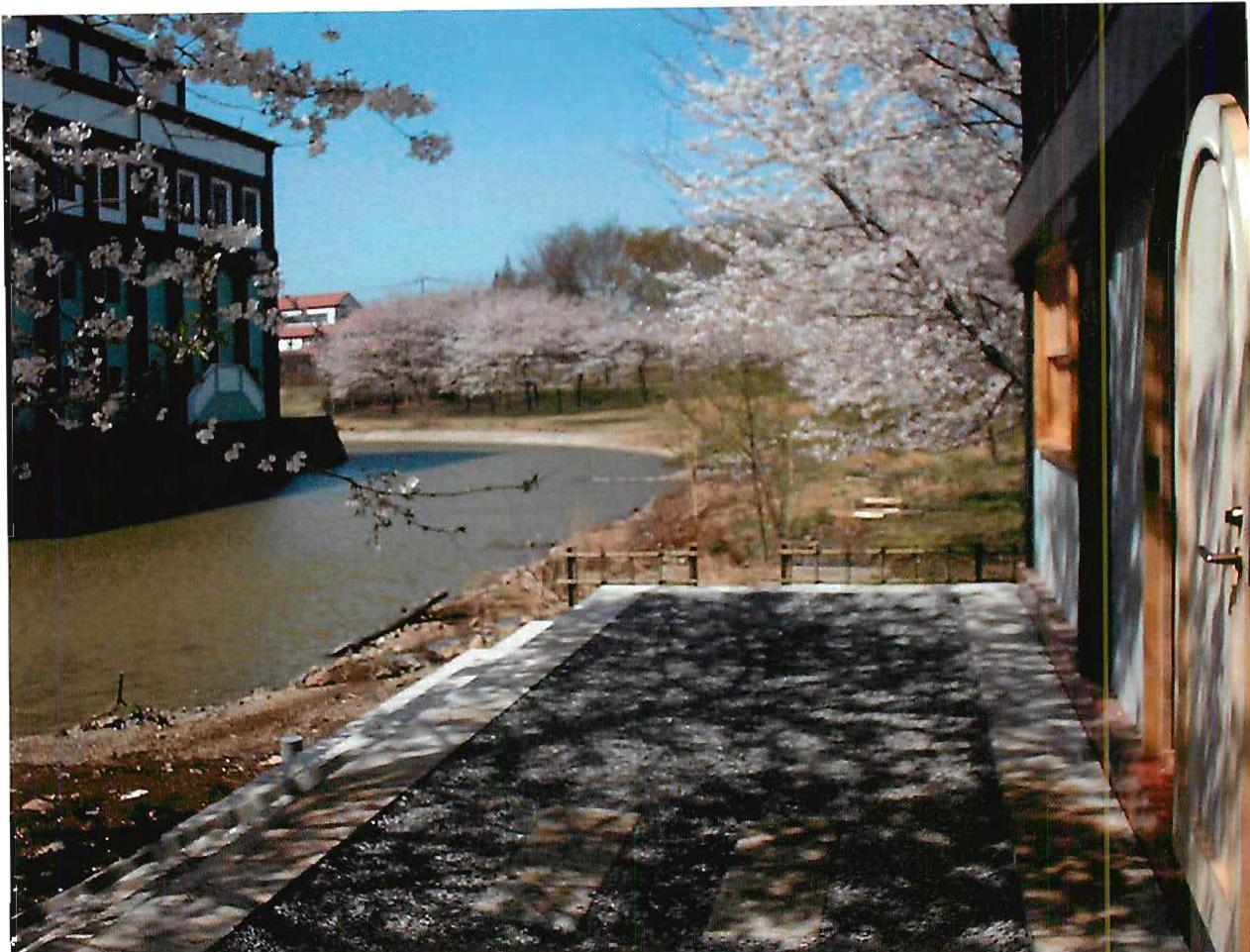

Like the great historical examples of China, southern England, Japan, this vision anticipates a new "created" land all over the surface of the Earth, which has the characteristics of nature, preserves the aspects of nature which are profound, and yet integrates roads, airports, buildings, gardens, walls into nature so that the human-made and the natural interpenetrate and support each other.

To my mind, the most unexpected aspect of this vision of living structure is that it shows a city or a region created by the repeated application of a single class of processes. One deep class of processes — infinitely varied — does everything. Let me repeat the definition of living processes which I have given in Book 2. The living processes are all those processes of step-by-step adaptation — used in the design and planning and construction of the environment — through which living structure can be made.

I am proposing that in the course of all planning, building, conceiving, designing, landscaping, or making a building, throughout, at every stage, all the processes are composed of millionfold repeated applications and combinations of a single type of unfolding process, governed by certain transformations which make each center help the larger centers and thus keep creating living wholes. I believe all living processes are sequences, or combinations, or combinations of combinations, of this kind of unfolding process.

The core of the matter lies in the way that centers are being formed. The point of all living processes is that the next bit of structure which is injected to transform the existing wholeness must always extend and enhance the wholeness by creating further positive living centers. This process of enhancing wholeness is a process which is, if you like, a kind of universal template for all life-creating processes.

THE FUNDAMENTAL PROCESS

- At each step, the process begins with a perception of the whole. At every step (whether it is conceiving, designing, making, maintaining or repairing) we start by looking at and thinking about the whole of that part of the world where we are working. We look at this whole, absorb it, try to feel its deep structure.

- Within the whole, we consider the latent centers which might be worked on next. These latent centers, are dimly, partially visible, large, medium, and small.

- We choose that one of these latent centers which, if established or strengthened next, will do the most to give the whole an increase of life. We work to intensify that living center, intensifying it in a way which, we judge, does the most good to the whole.

- At the same time that we try to enhance the living quality of this chosen center, we also try to make it intensify the life of some larger center that it belongs to.

- Simultaneously, we also make or strengthen at least one center of the same size as the center we are working on, and make it positive, next to the center we are currently concentrating on.

- Simultaneously, we also start to see, and make, and strengthen smaller centers within the one we are working on — increasing their life, too.

- Once the whole has been modified by this operation, we start again.

All living processes, in my definition, are combinations and sequences of this fundamental process.

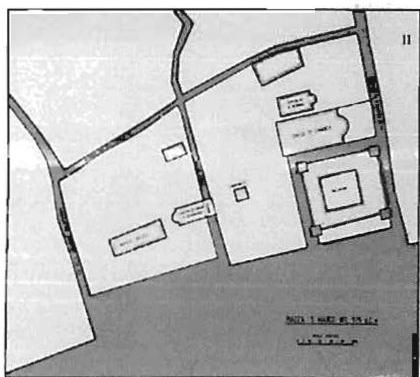

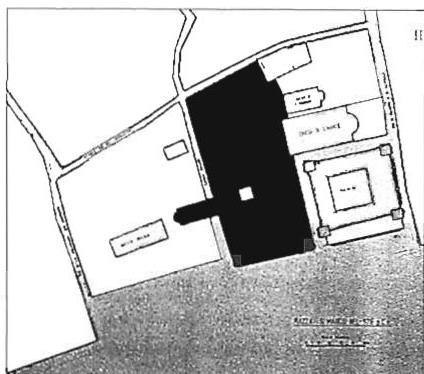

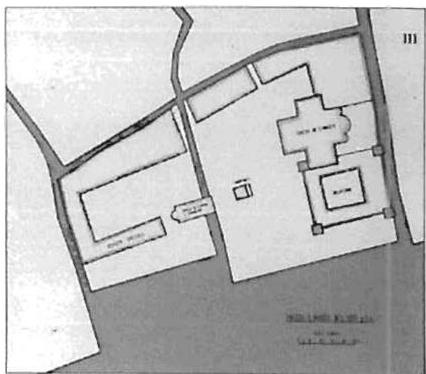

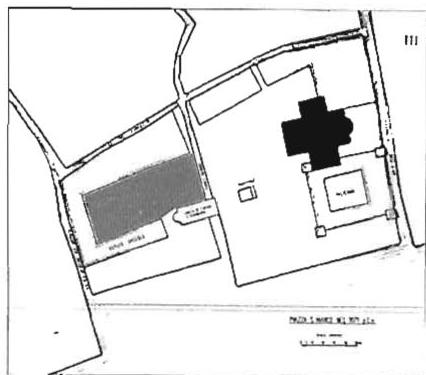

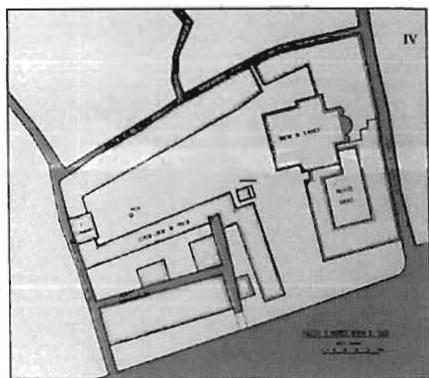

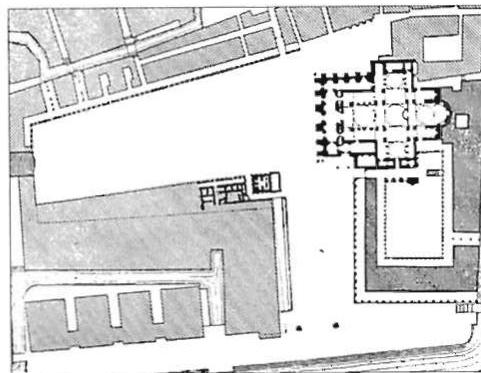

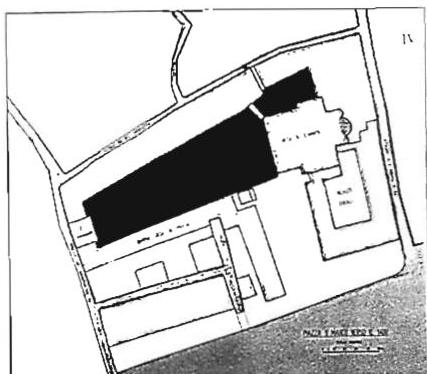

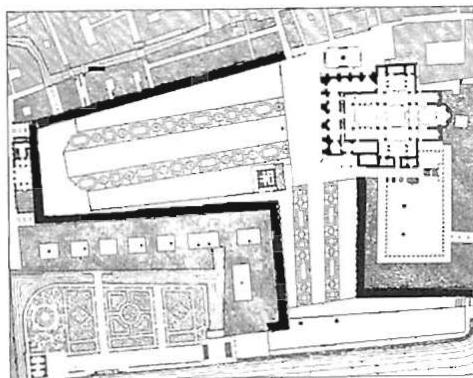

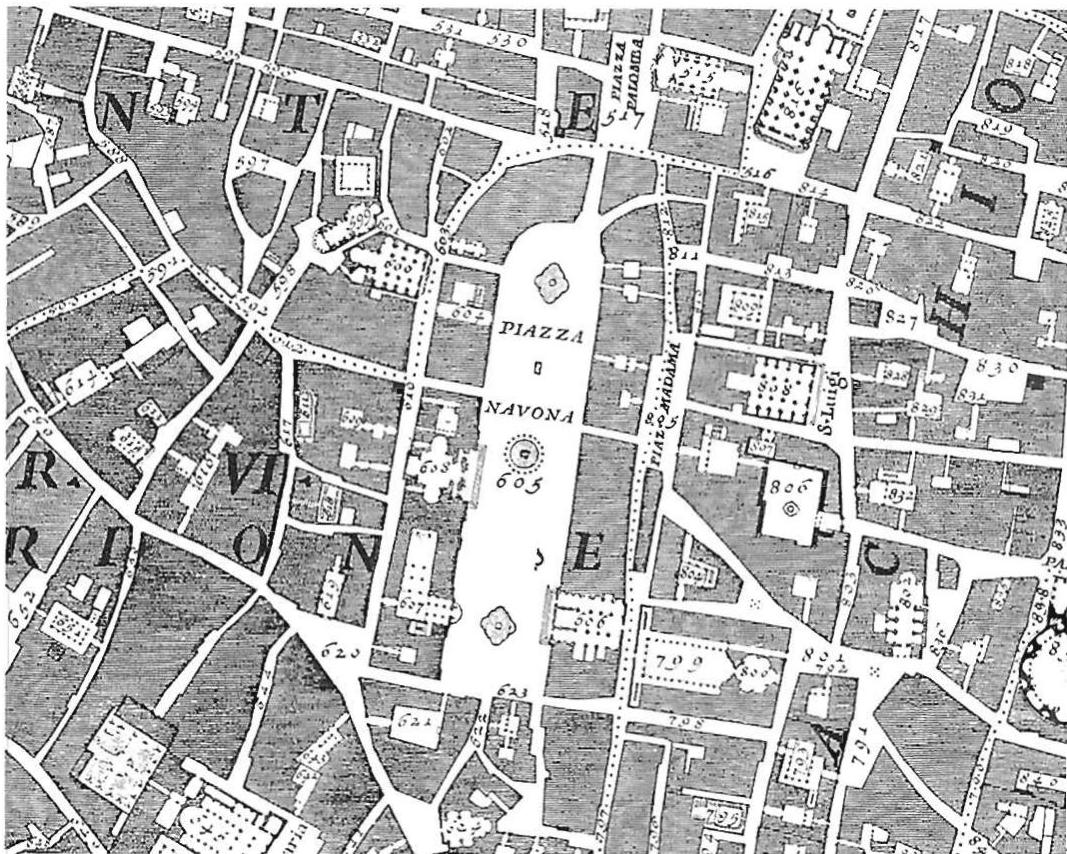

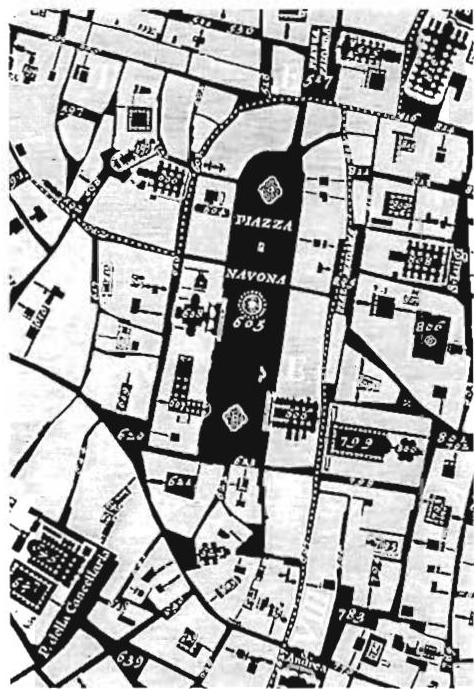

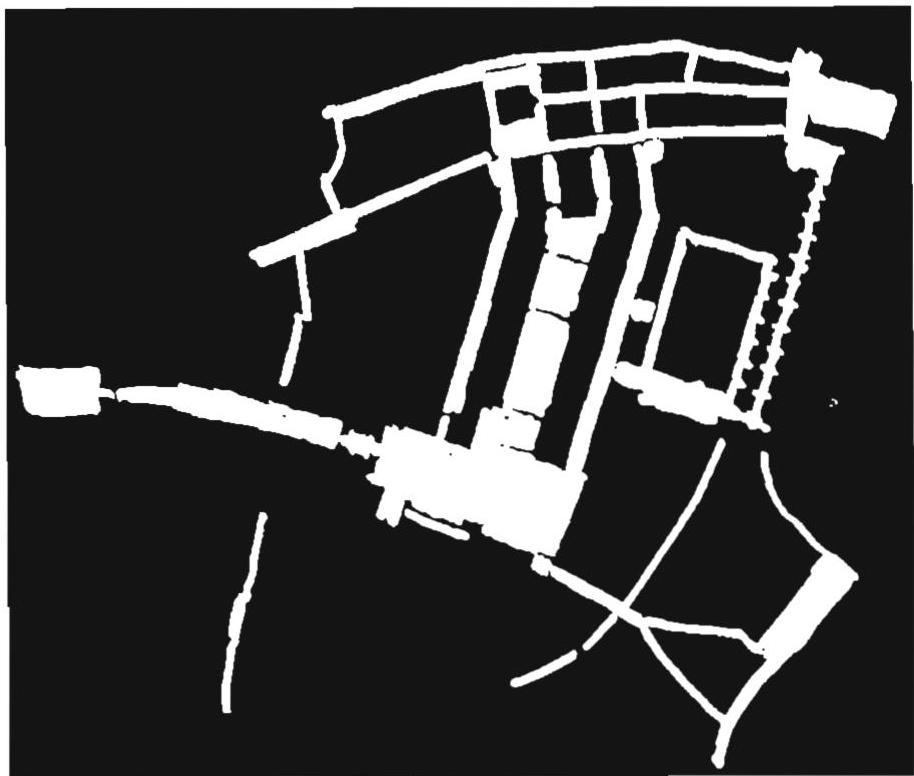

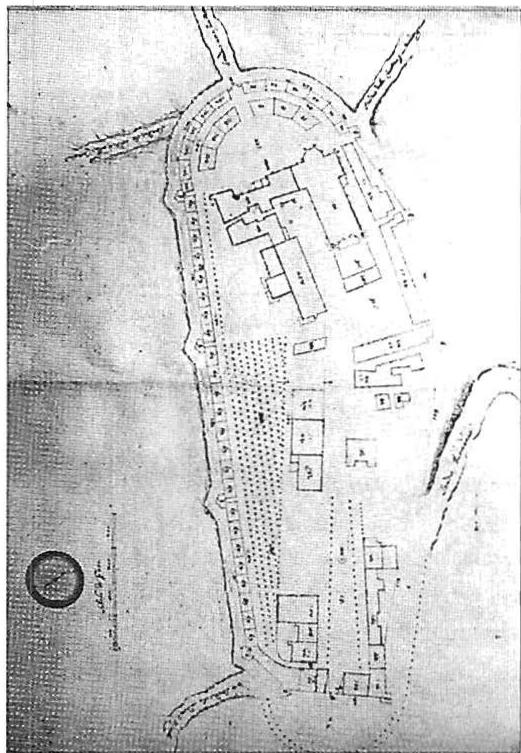

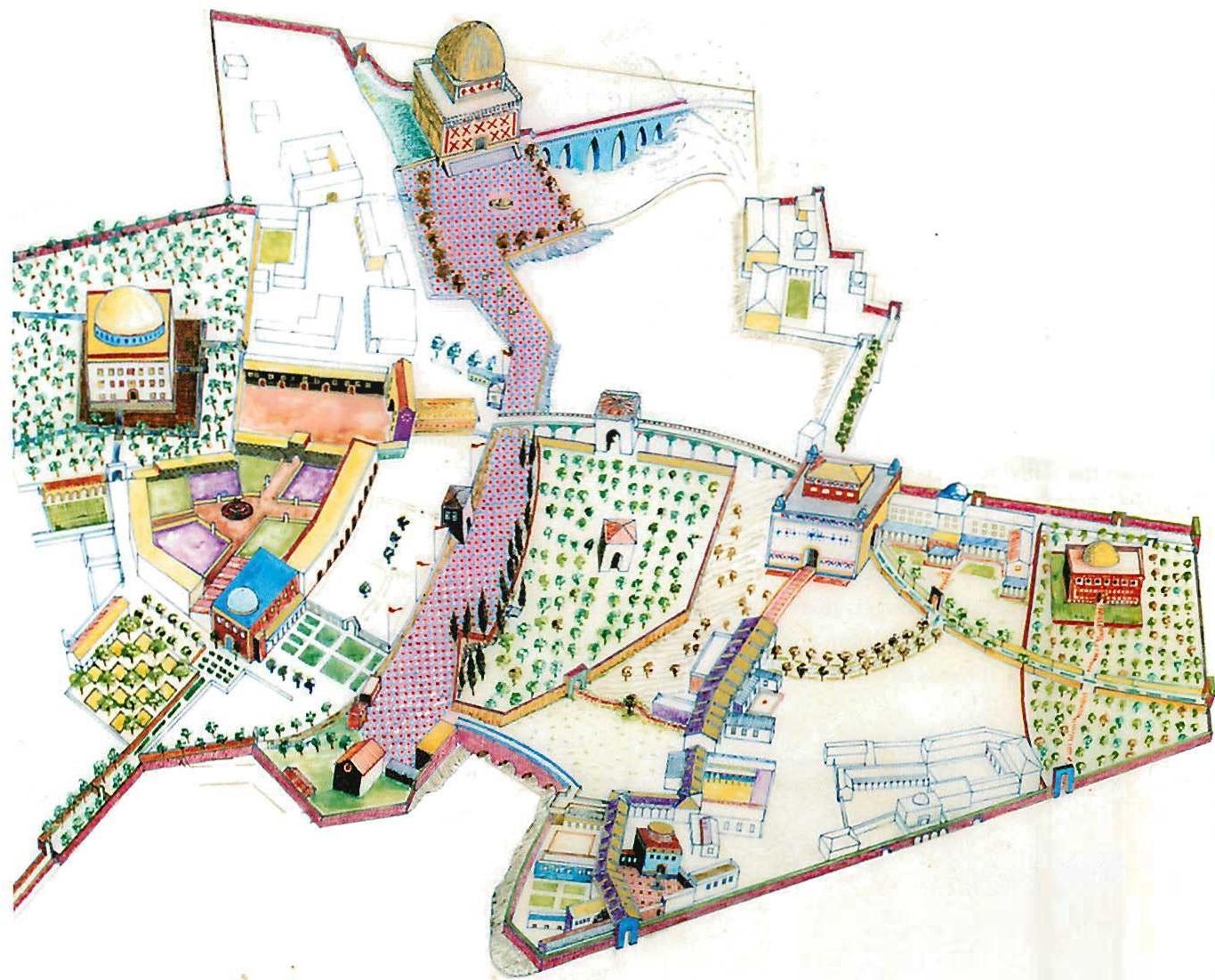

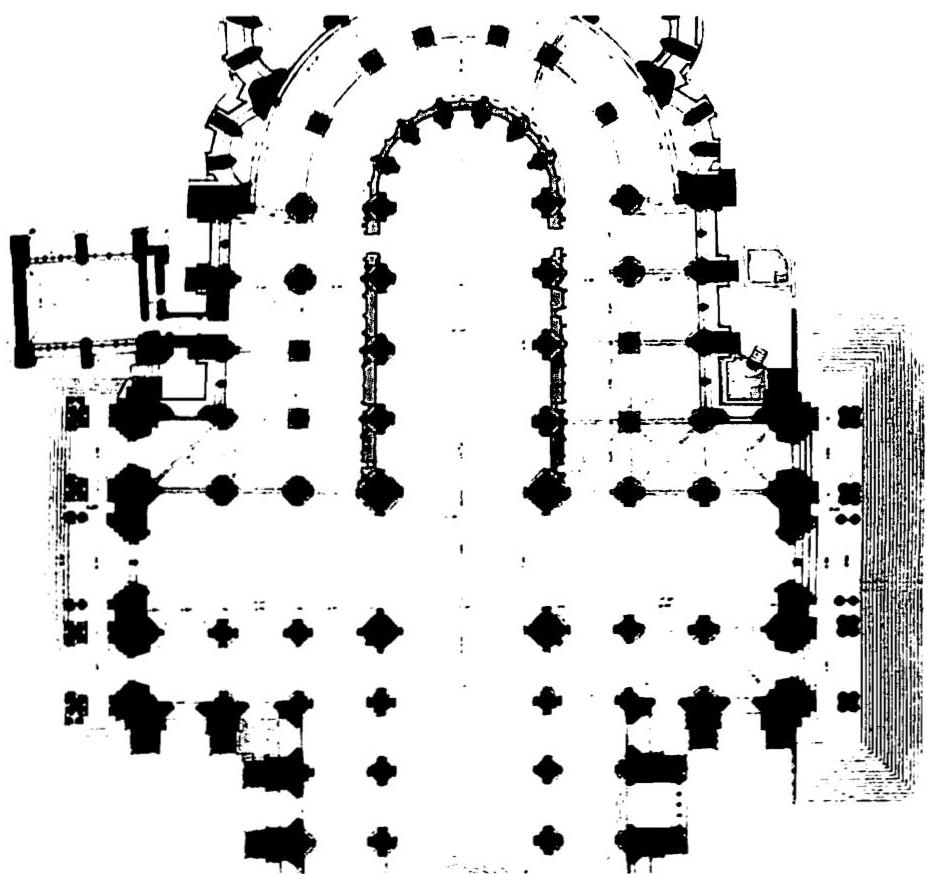

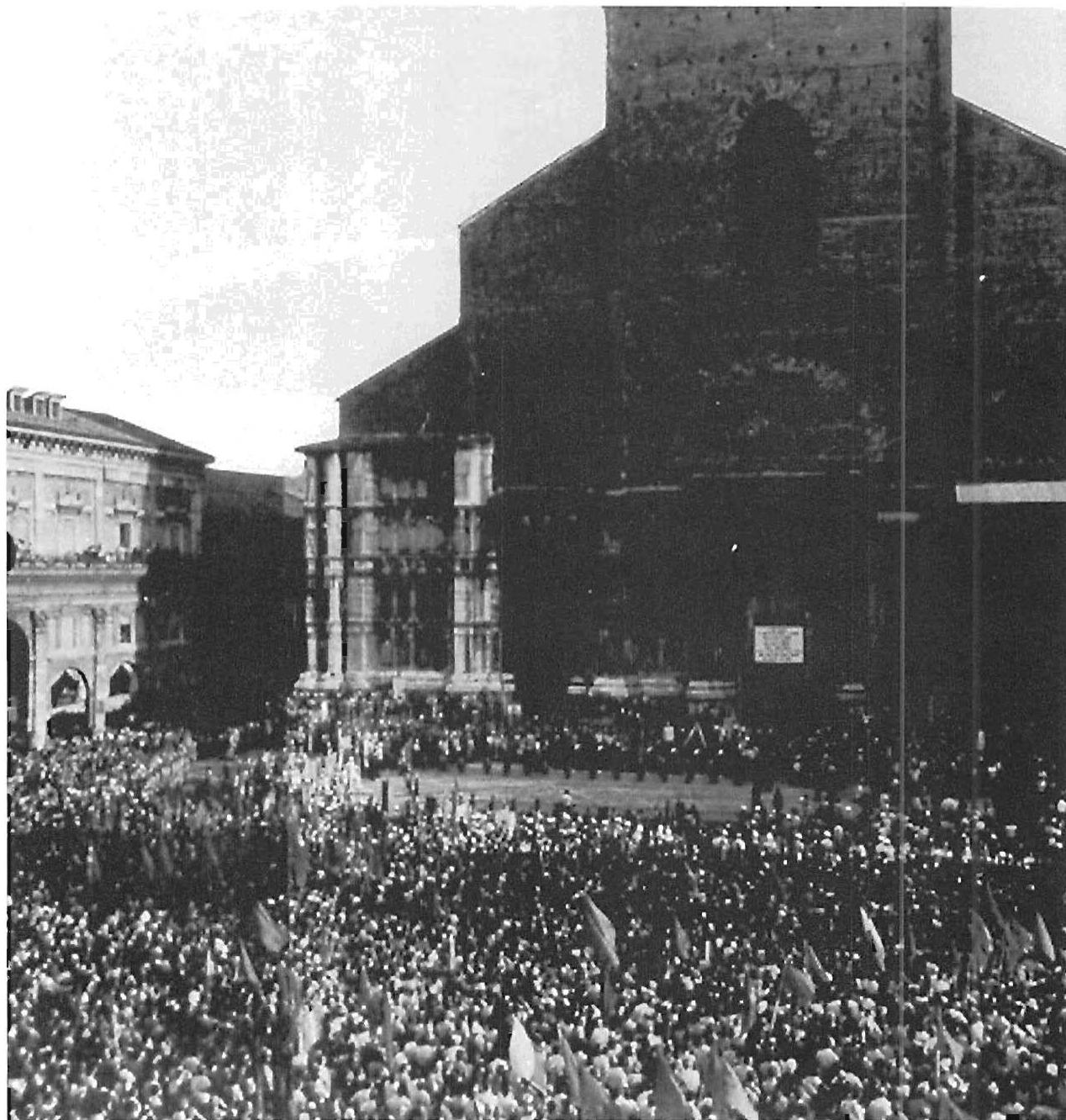

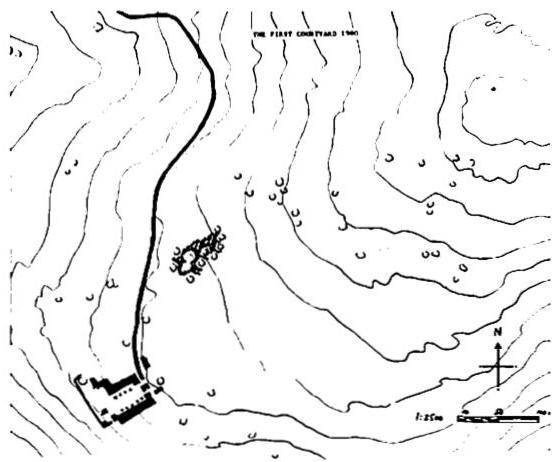

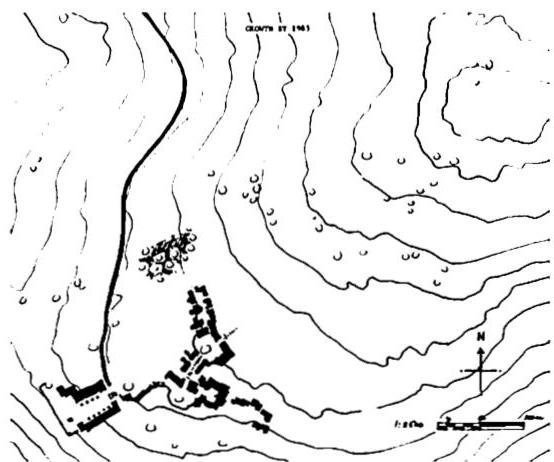

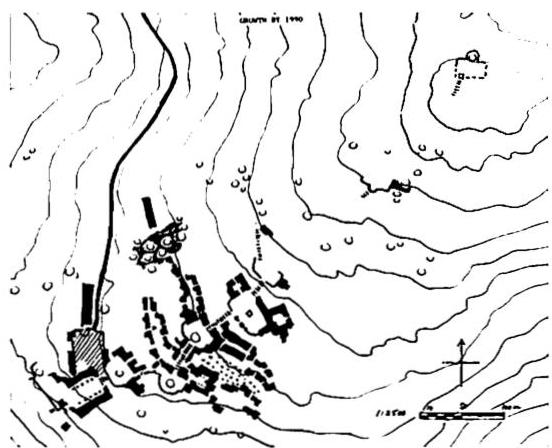

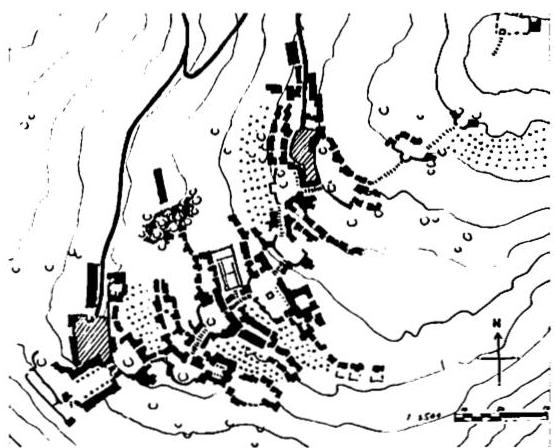

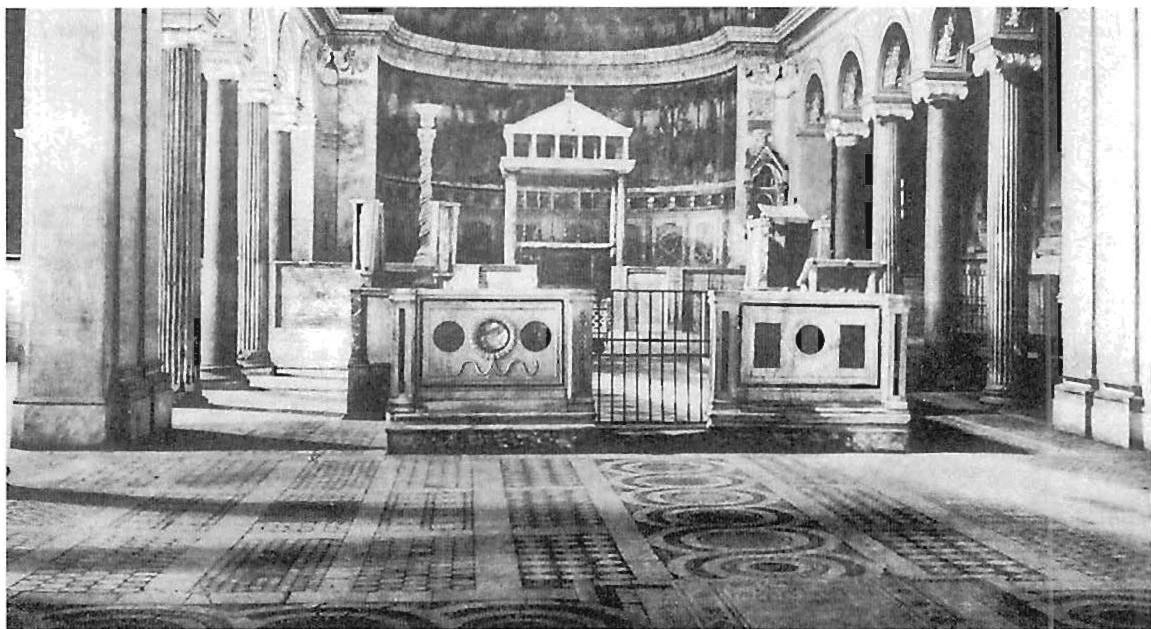

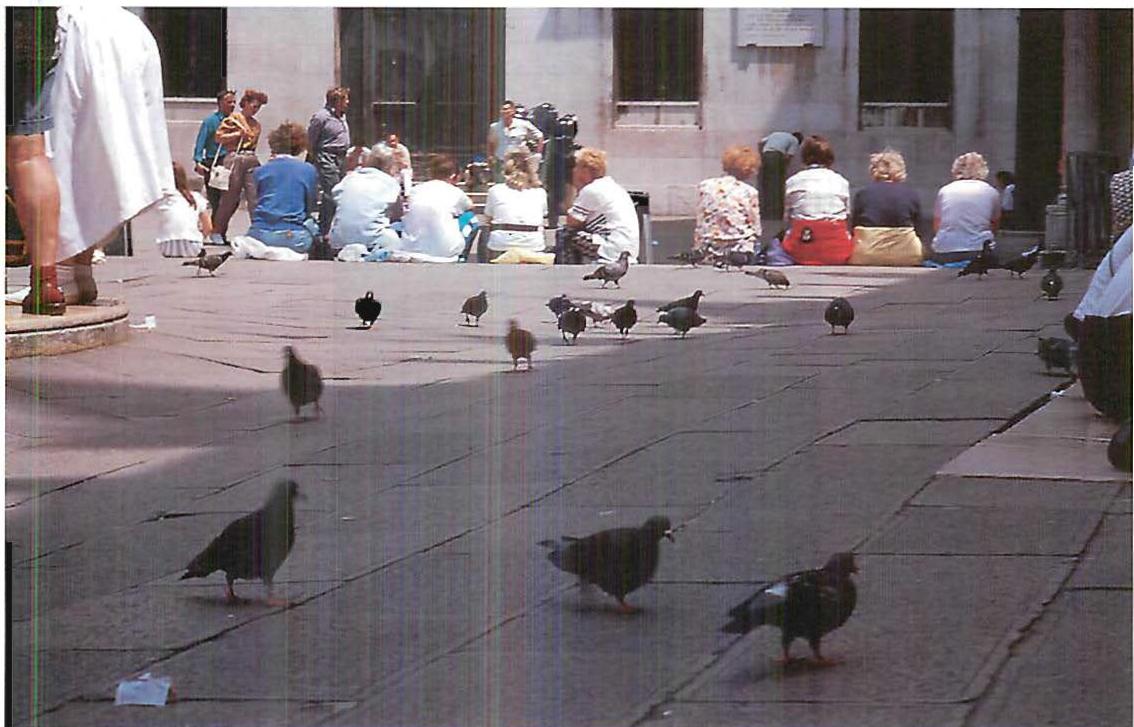

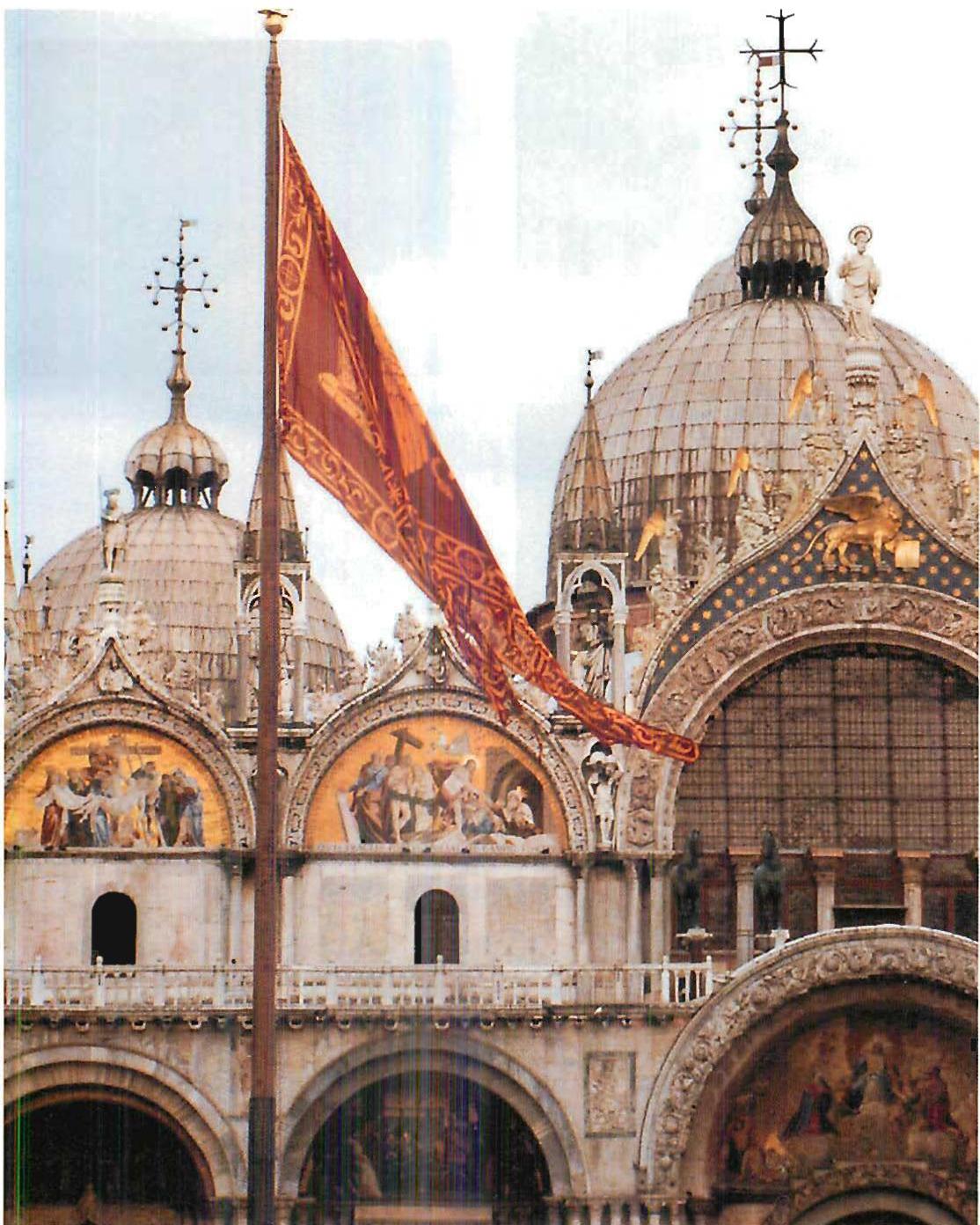

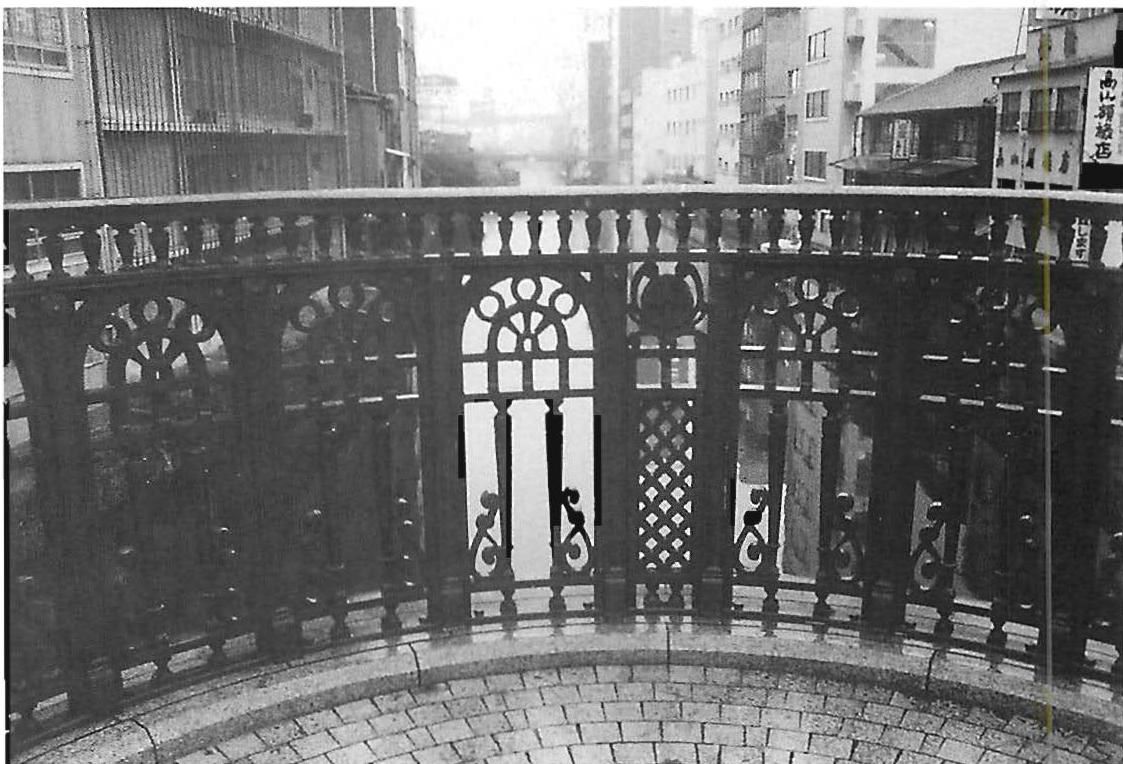

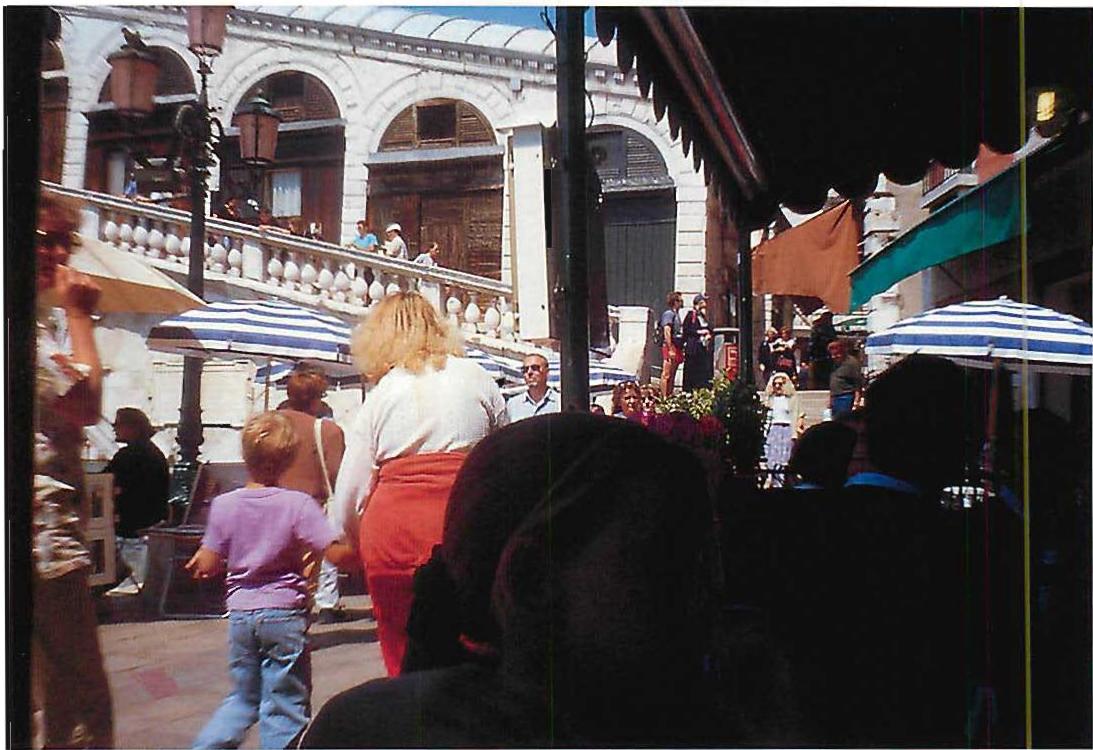

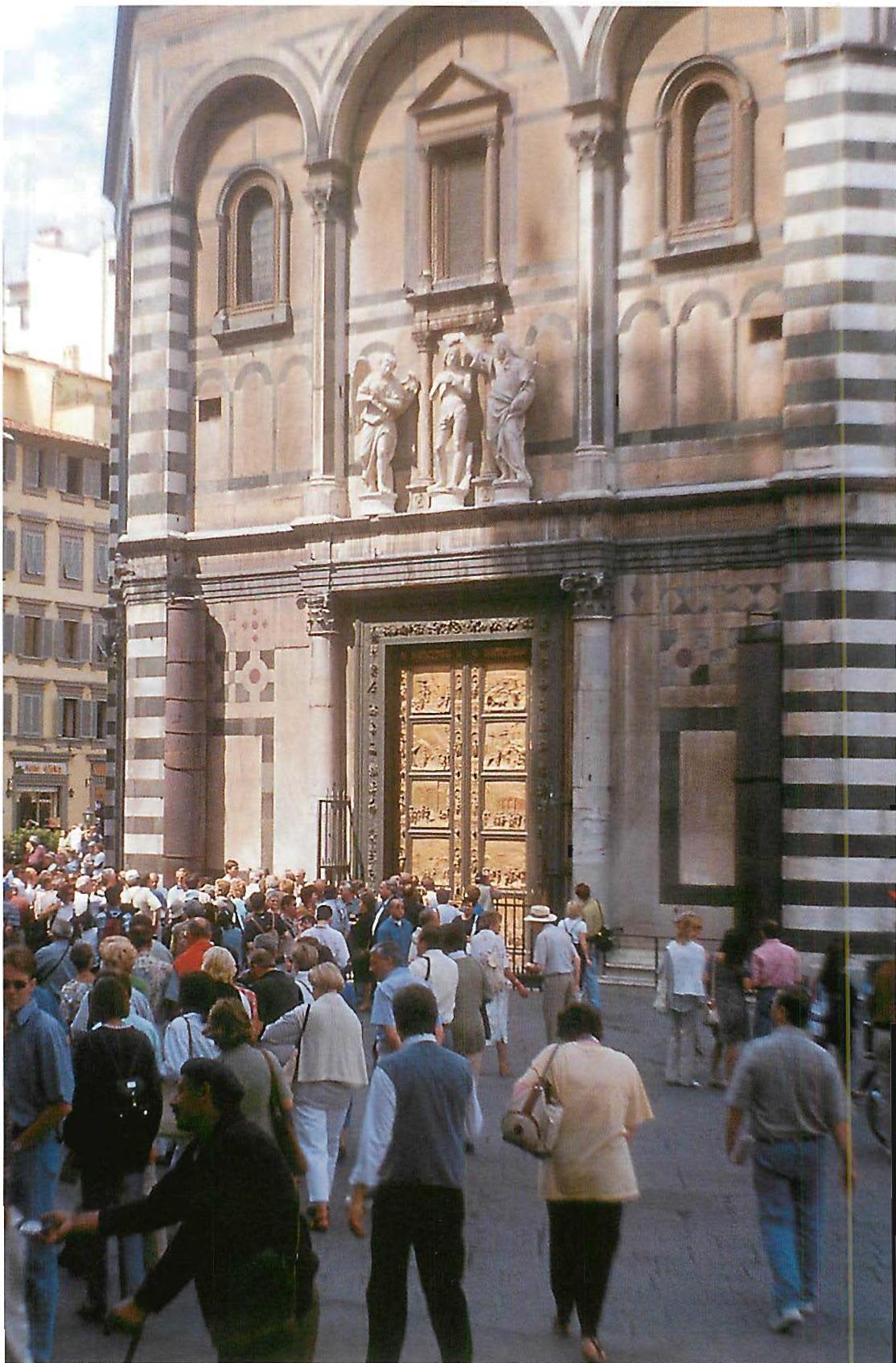

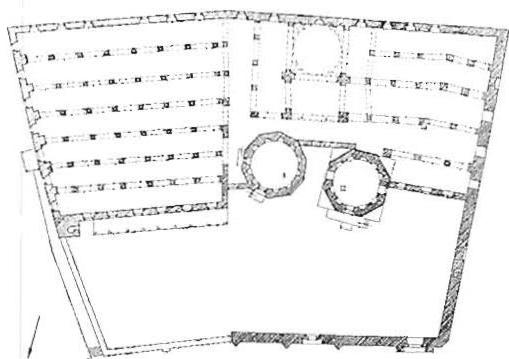

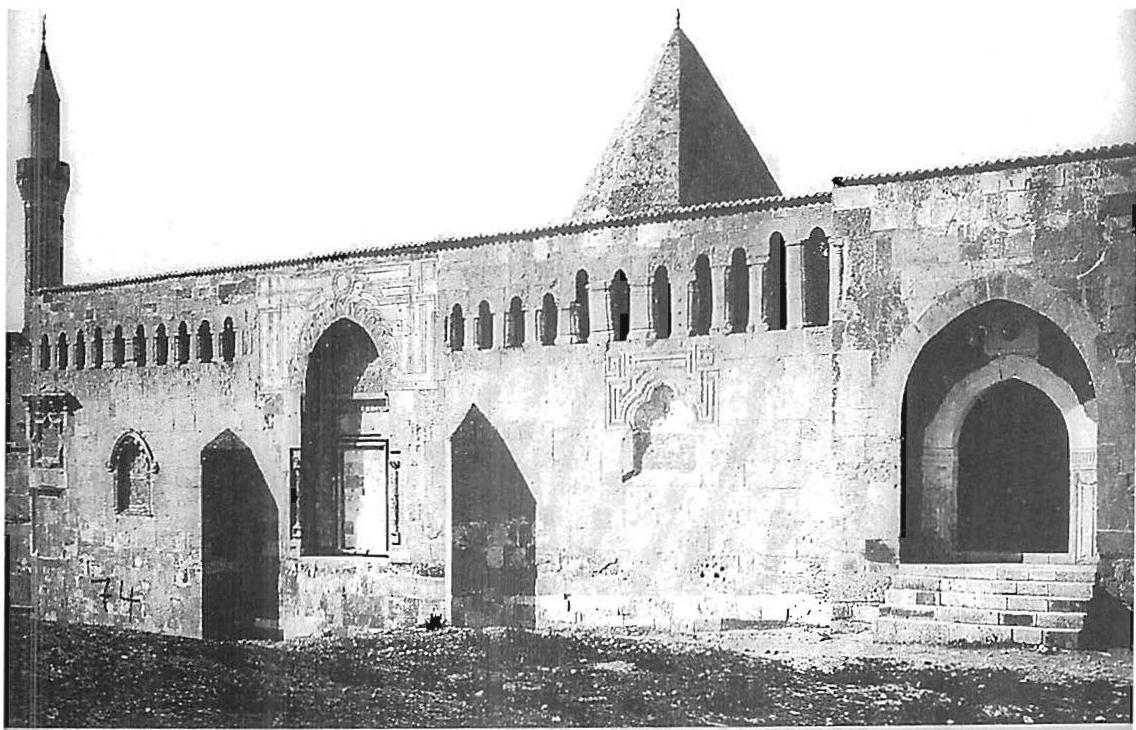

3 / A HISTORICAL EXAMPLE OF A LIVING PROCESS: EVOLUTION OF ST MARK'S SQUARE

You may get a feel for the character and impact of living process from the history of St Mark's Square in Venice. I have discussed this case in detail in Book 2, pages 252-54, but I repeat it here, in summary form, for any reader who has not seen the earlier discussion.

In this particular case, living processes (all repeating versions of the fundamental process) were active for a period of eleven centuries to reach the results we know today. Here are some highlights.

Stage 1, 560 A.D. The process started with a small square island. A small basilica was placed on it, forming an early symmetry, and a powerful center. The basilica was made symmetrical.

The castle of the Doge (lower right on the following pages) was built as a symmetrically square building surrounded by a square canal forming a second, also powerful, center.

Stage 2, 976 A.D. Two new buildings were added, both forming powerful centers. Both were axially symmetrical (with rough bits to make them fit). Both were added in such a way as to make the space to their left a near-perfect rectangle, itself thus forming a new and powerful center in the space. The land of this rectangle was pushed out into the Grand Canal, strengthening the center still more by its dovetail with the water. A tower was built (yet another center) roughly at the center of the rectangle.

angle (not quite), to form a powerful focus in the most visible place. It is on axis with the church to the left, thus forming yet a further center in the space created between the tower and this left-hand church.

Stage 3, 1071 A.D. to 1309 A.D. An additional rectangular building is built to close and shape

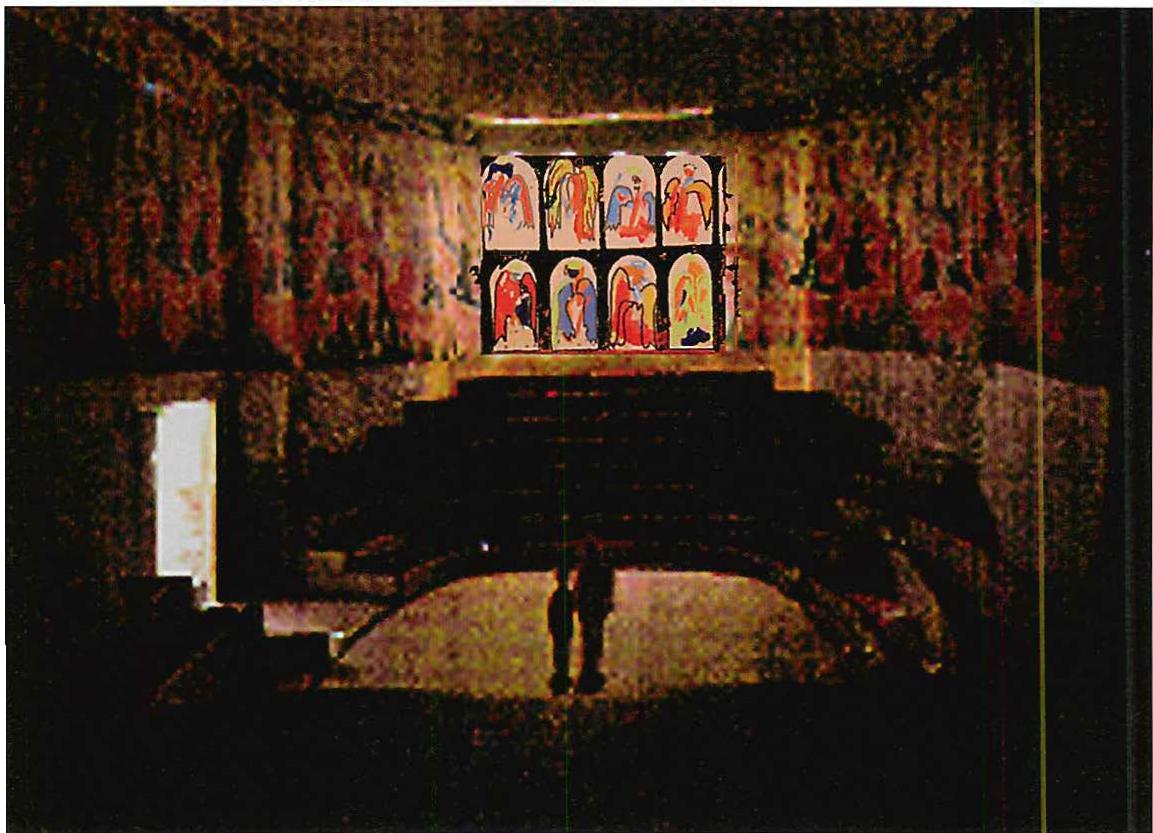

the top end of the square. For the first time the island on the left of the small canal is enclosed by a three-sided building, creating a second square (yet another powerful center) attached like a tail to the first square, focussing attention on the basilica of St Mark's. This created for the first time the enormously powerful center we now know as St Mark's square. The church of St Mark's itself is given cruciform arms (transepts), each one again symmetrical, and therefore working as a center. The land that had earlier been pushed out into the Grand Canal was now extended further to give the whole assembly a kind of apron into the Grand Canal, which gave the complex an approach that was itself a new and stronger, more powerful center when seen from the water.

Stage 4, 1400 A.D. to 1532 A.D. The tower became embedded in a rectangular building which sharpened and narrowed the square and

the view towards St Mark's from the water. St Mark's became further thickened, strengthening its impact on the square, and increasing its strength as a center. The Doge's palace was extended so that together the palace and the offices form a more coherent space which itself was even stronger than before, as a center. The campanile was left in the angle of the new-formed office building so that it still stood clear, forming the most powerful center possible seen from miles around.

Stage 5, after 1532 A.D. The building on the left was thickened, even more, with office and houses behind, clarifying its own structure as a center and that of the square which it contained. The lower building was rebuilt, pulled away from the tower, given many interior centers in the form of courtyards. The gate at the left-hand end of the square was rebuilt entirely, so that the great arcades around the

long sides of the square formed long centers that focused attention fully on the church.

This particular example is an ancient one and it is very extended: the steps took place over a nine hundred-year period. However, I show it because it is well known, and because of its great historic interest. Please look at the more detailed explanation on pages 252-53 of Book 2. It is fascinating to see it.

What is vital is that this process of building St Mark's square was all made of center-creating actions, all were processes based in one way or another on the fundamental process. Most of the entities that were created there, large and small, were living centers that have unfolded over time to make the whole more and more vibrant, and it is this which gives the place its living character.

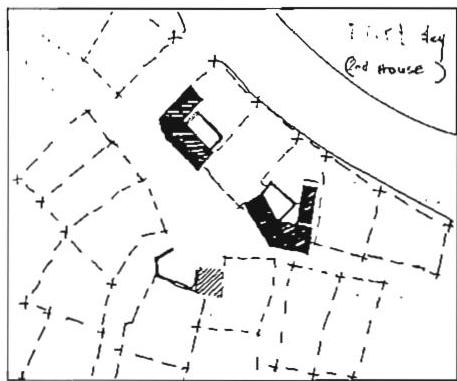

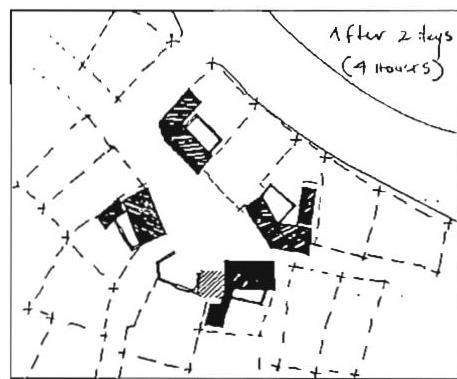

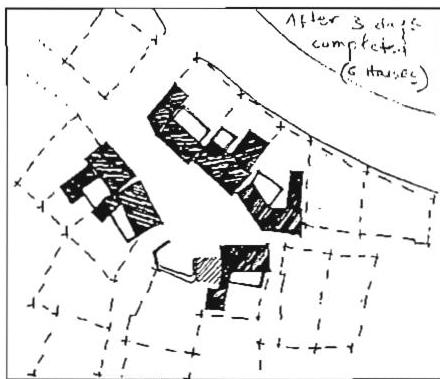

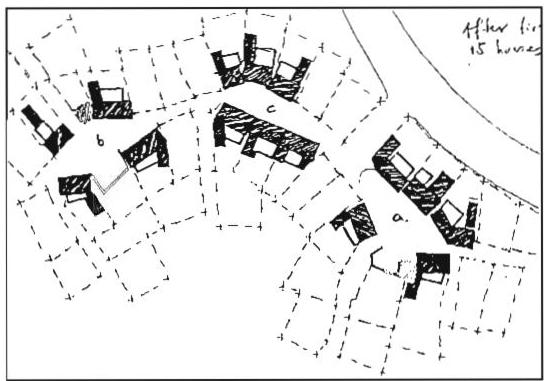

In the next section I show other examples of living process which have taken place over a period of a few weeks or months.

4 / EXAMPLES OF LIFE-CREATING PROCESSES FROM OUR ERA

When I write down in protocol language what is happening in a living process, as I have done on page 4, it possibly sounds too much like a formula. Obviously, I am not proposing that we go through life repeating this formula each time we do something, like blind idiots, just so that we can claim we are doing “a” living process.

Nevertheless it is true that the processes required to make a living thing are, at some very deep level, always similar in their essentials.

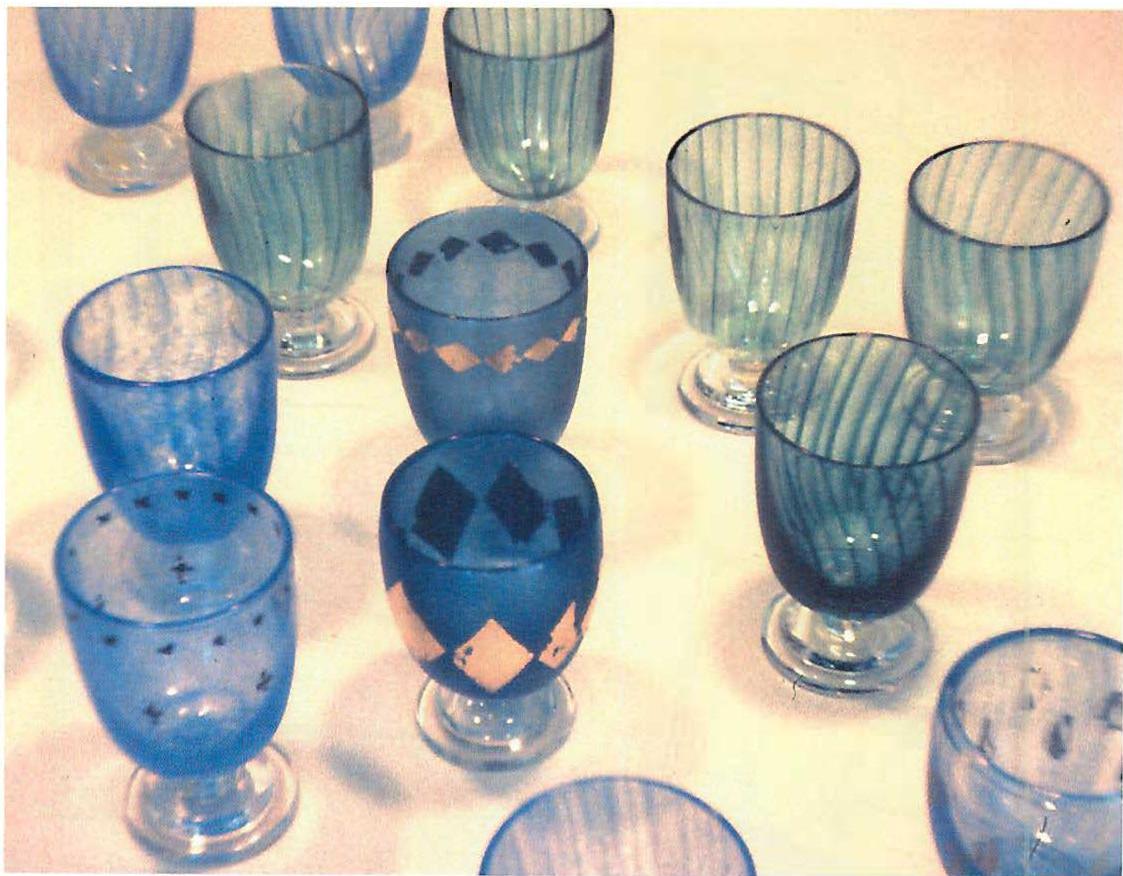

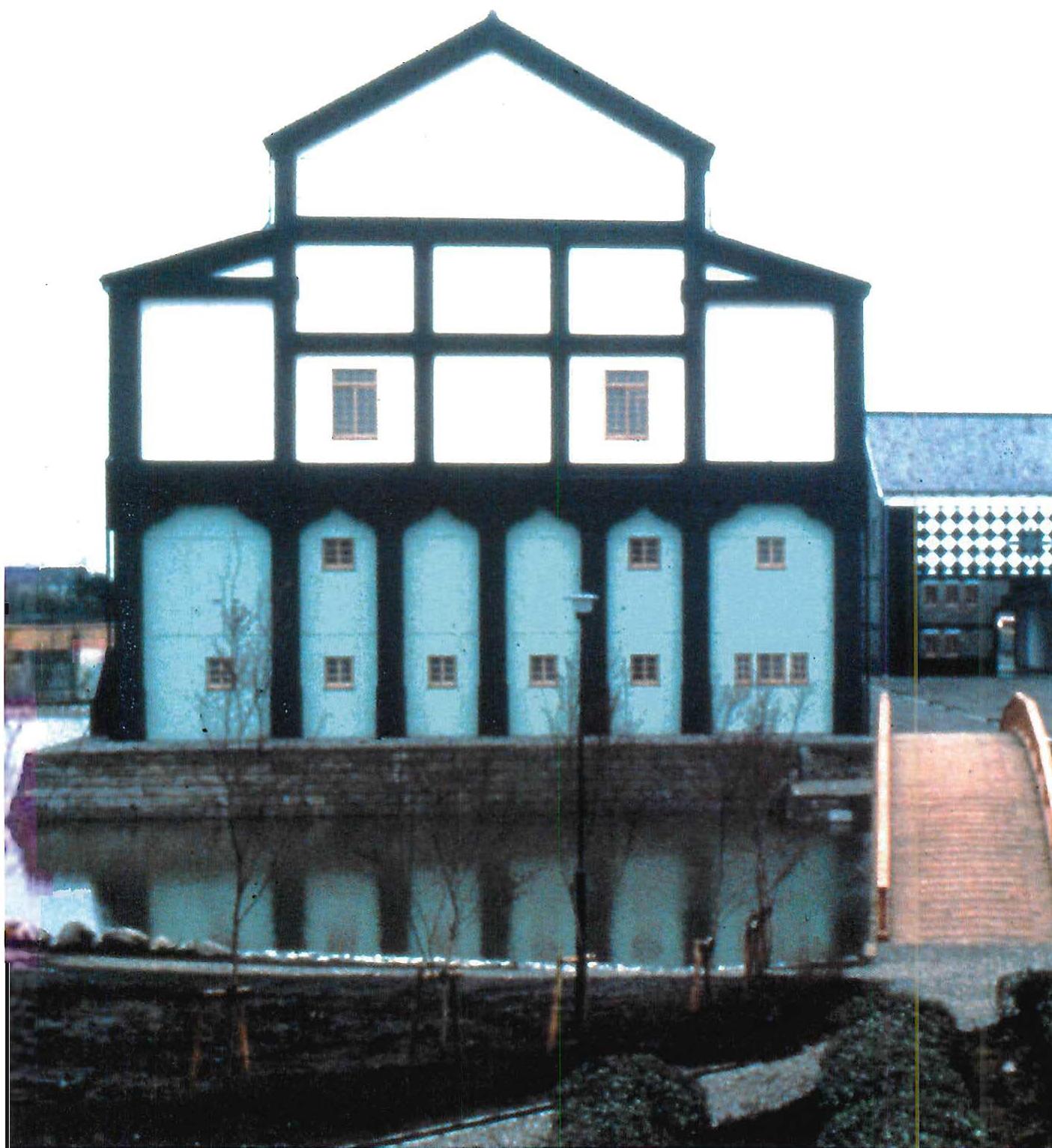

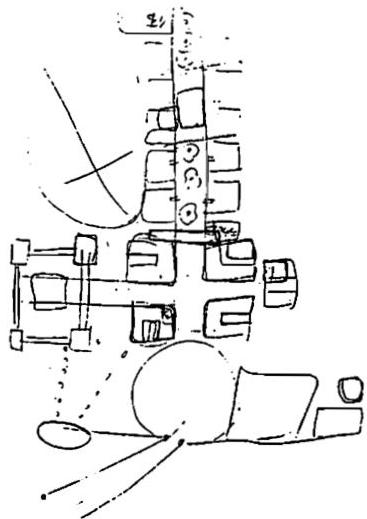

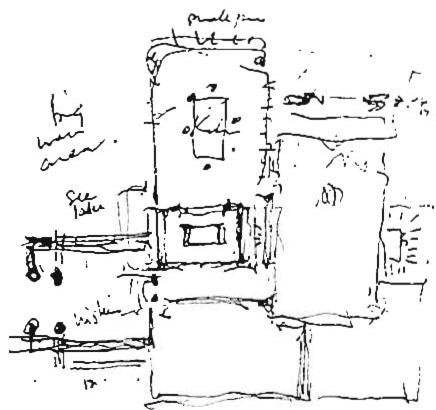

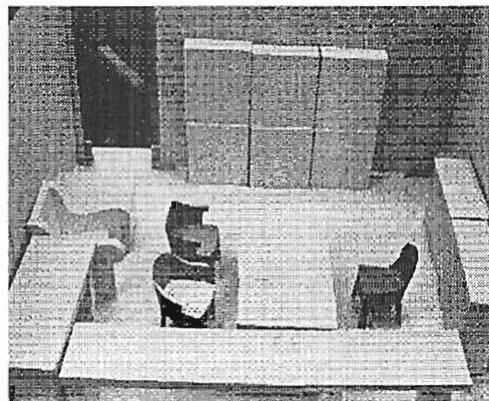

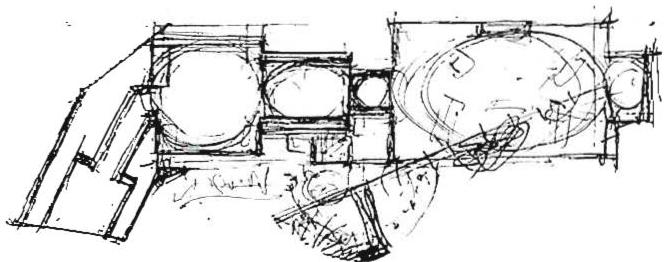

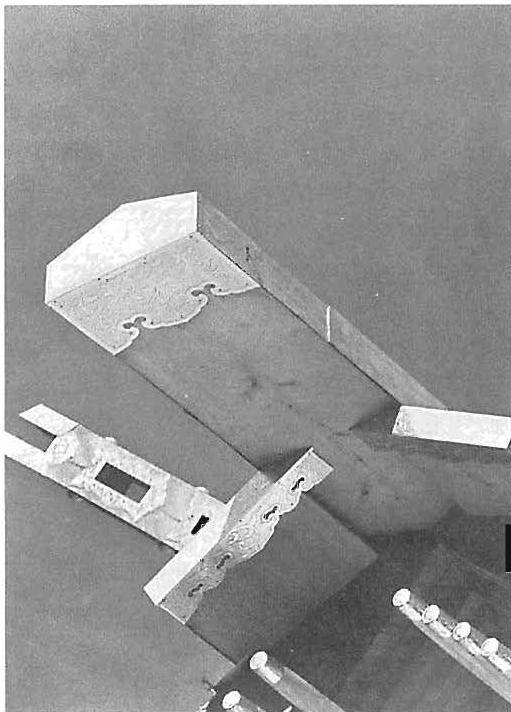

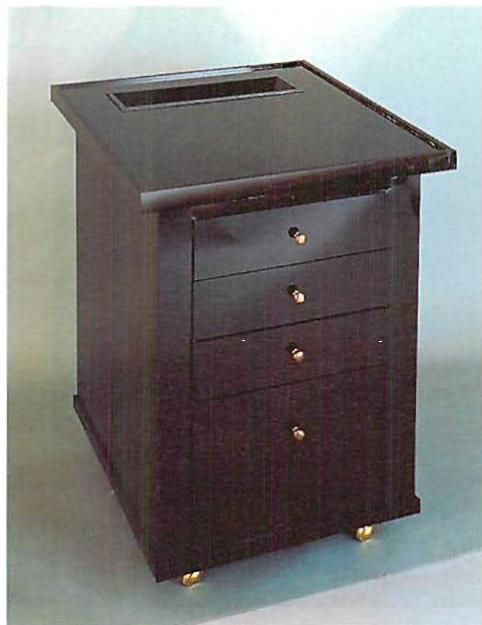

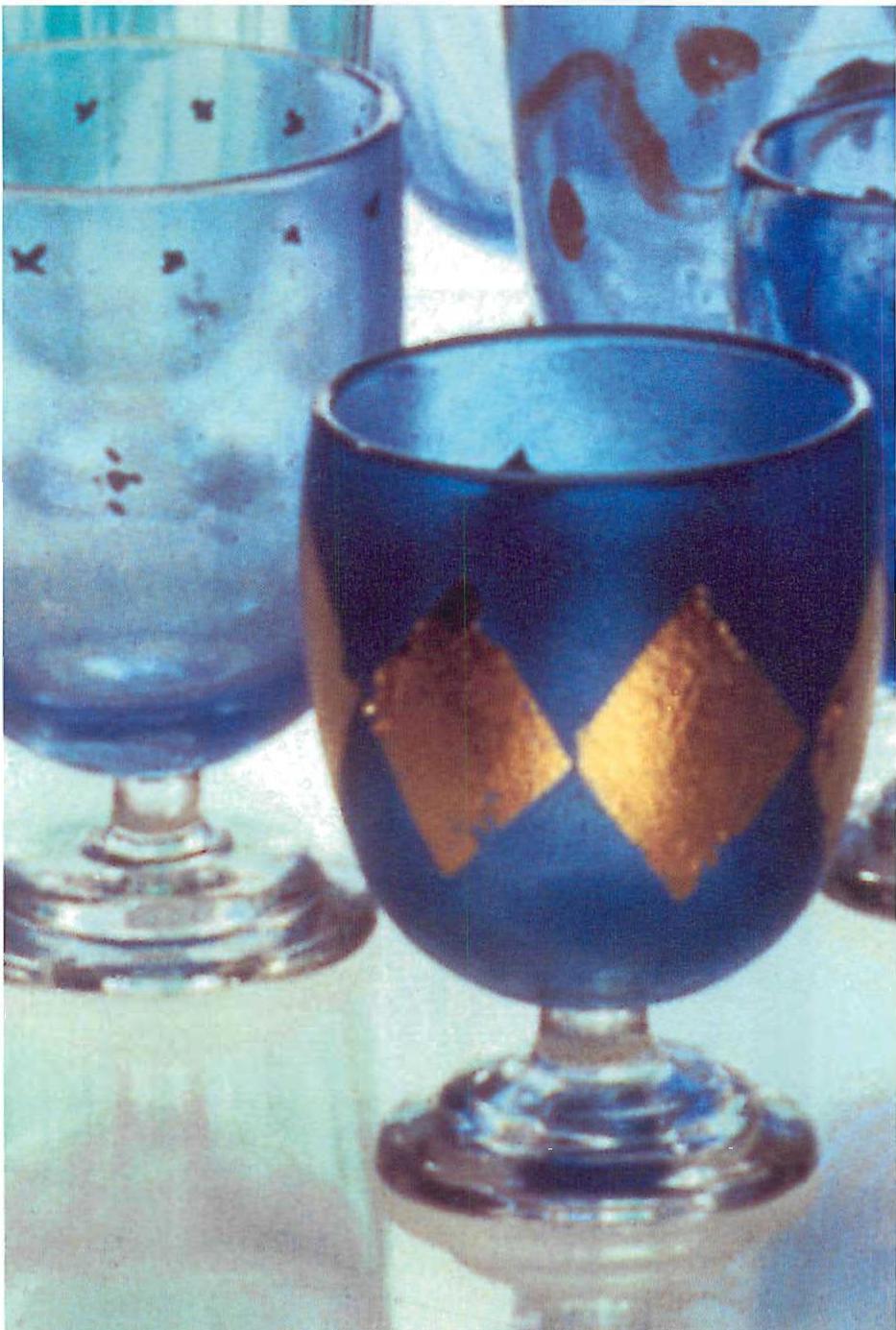

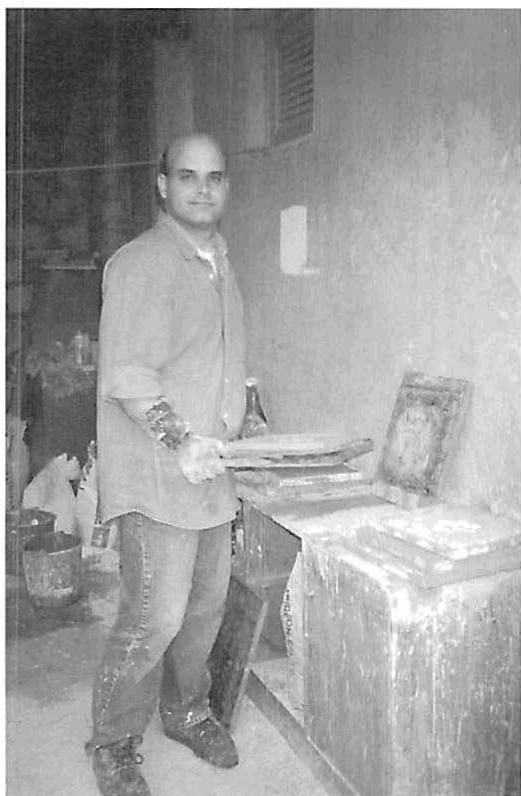

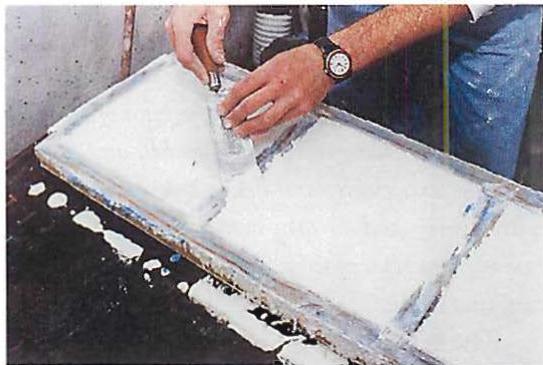

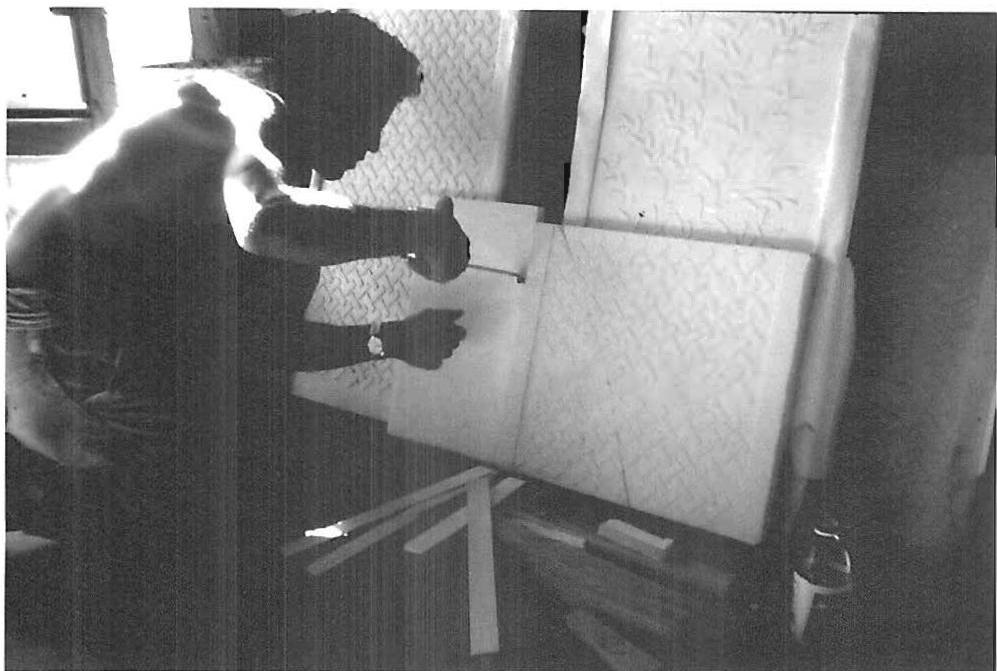

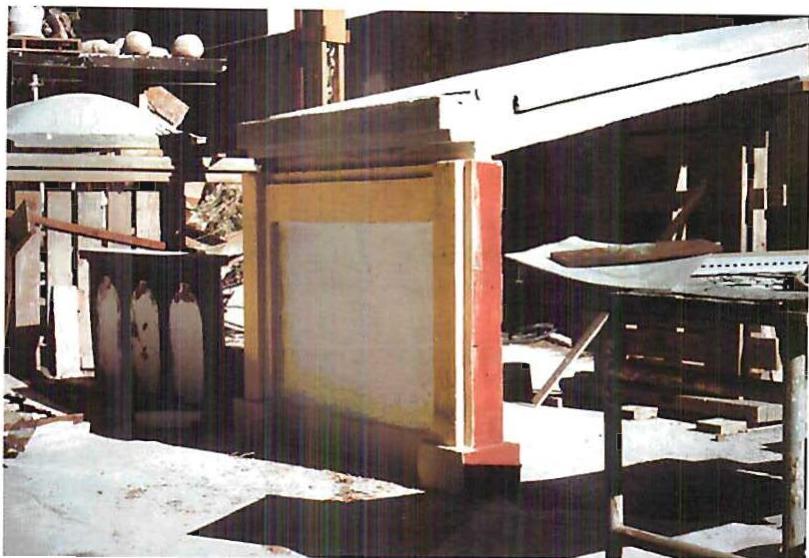

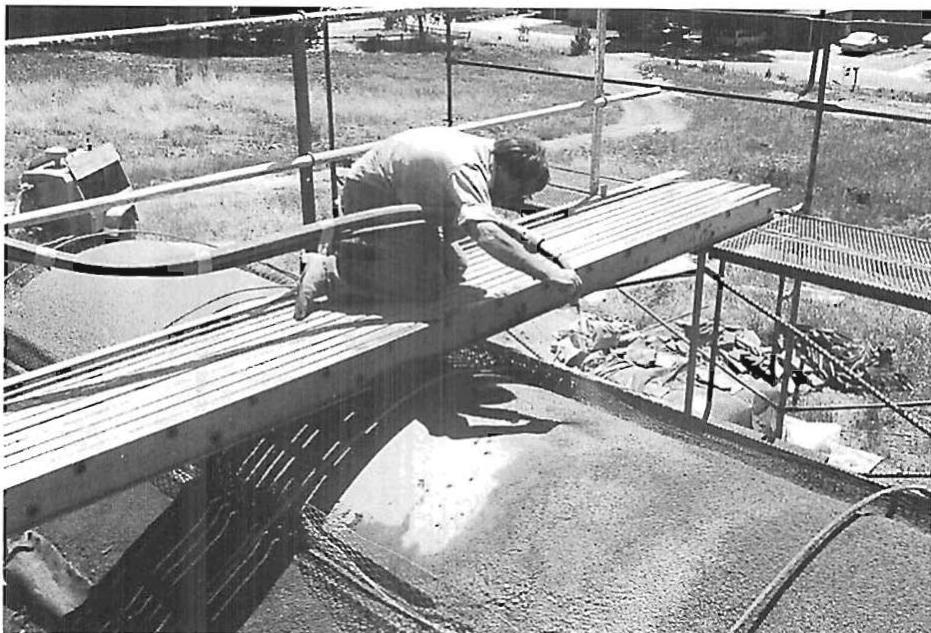

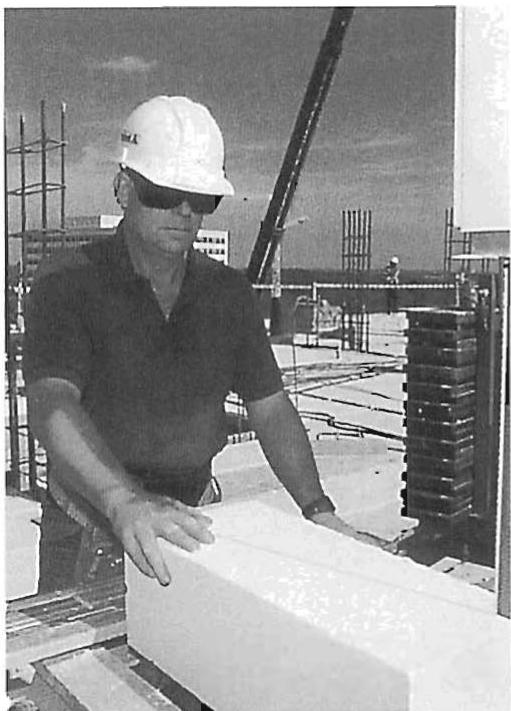

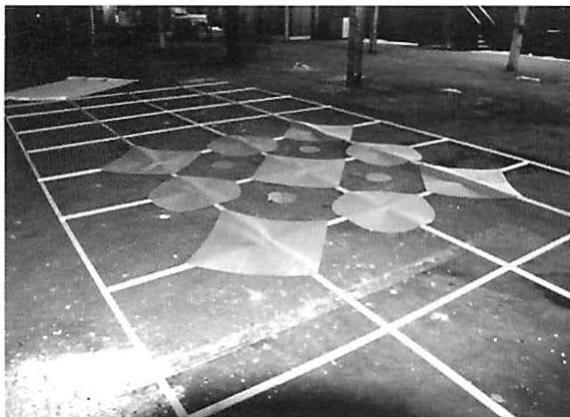

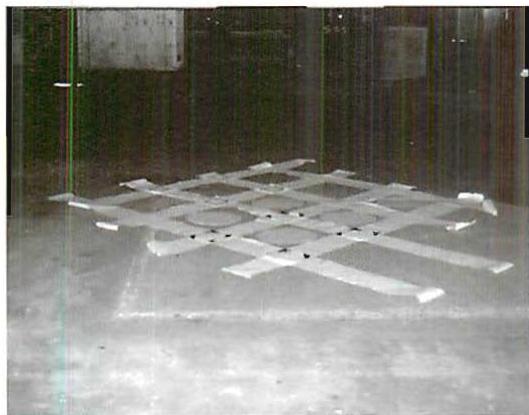

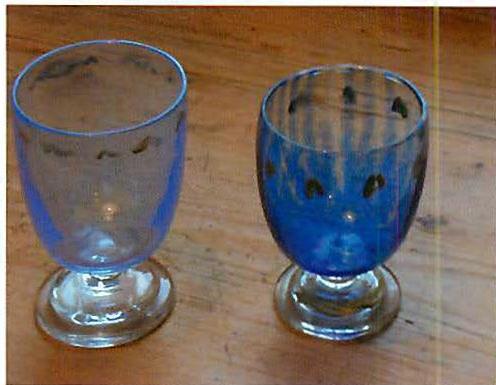

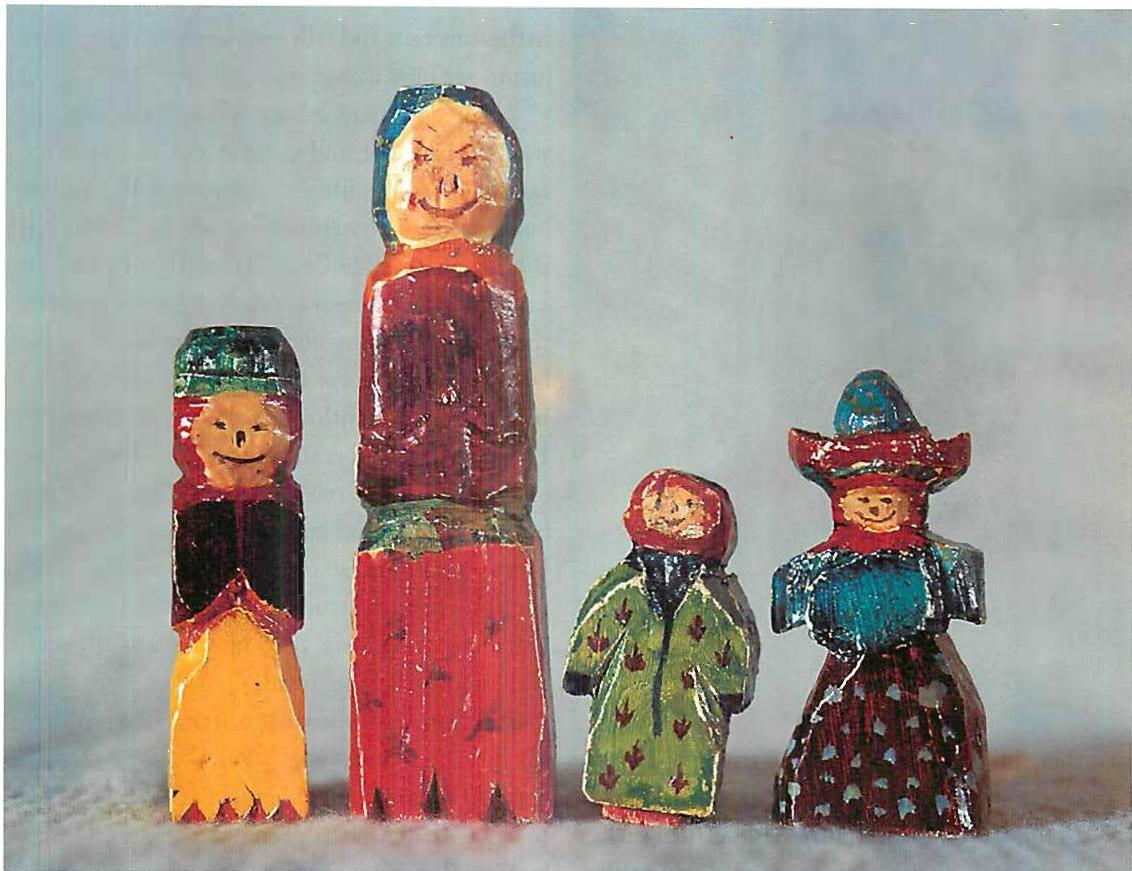

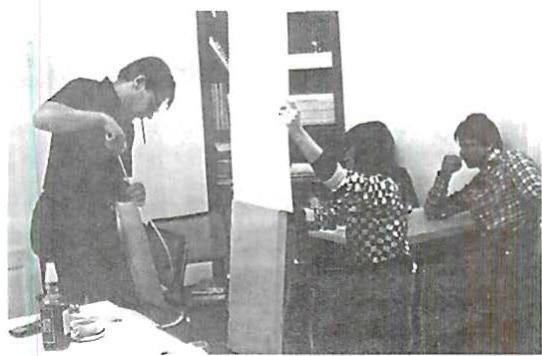

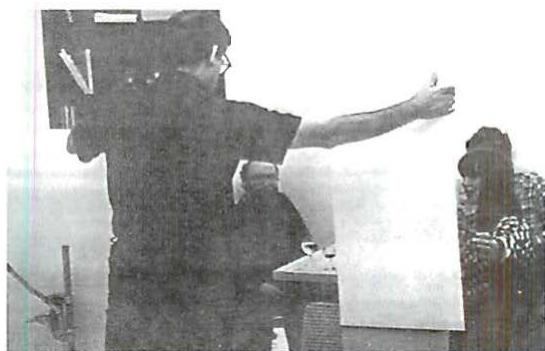

Even in the manufacture of objects, when it is done right, the fundamental process will appear. I show here a contemporary example of the use of process, lasting a few weeks, during which one of my colleagues and I designed a set of drinking glasses for the Royal Dutch Glass Works of Leerdam, Holland.

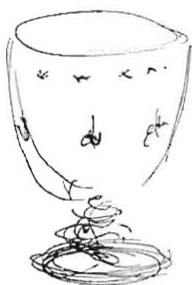

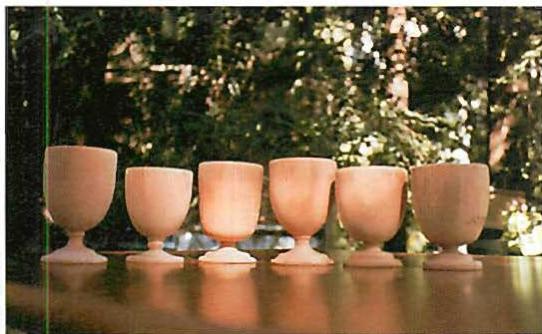

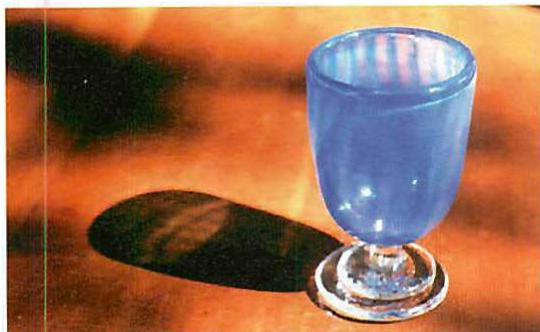

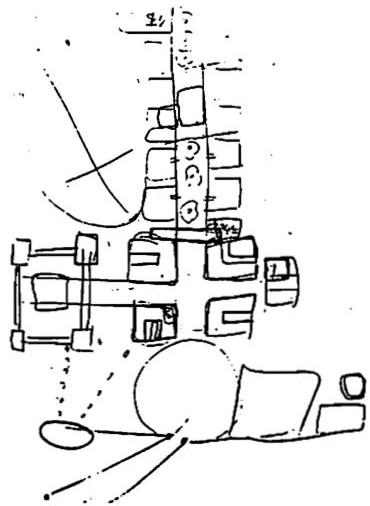

Here, in the process of designing a wine-glass, I started with a sketch. Already in this sketch several major centers that were to come were visible. Then we made many turned wooden mockups of the glass, getting the feel of the immensely subtle way that the sensation of the shape changes, even with what look like tiny variations in the curve and profile. Once again, it is living centers that I was judging — this time in relation to my hand as I imagined the glass when it had lemonade or wine in it.

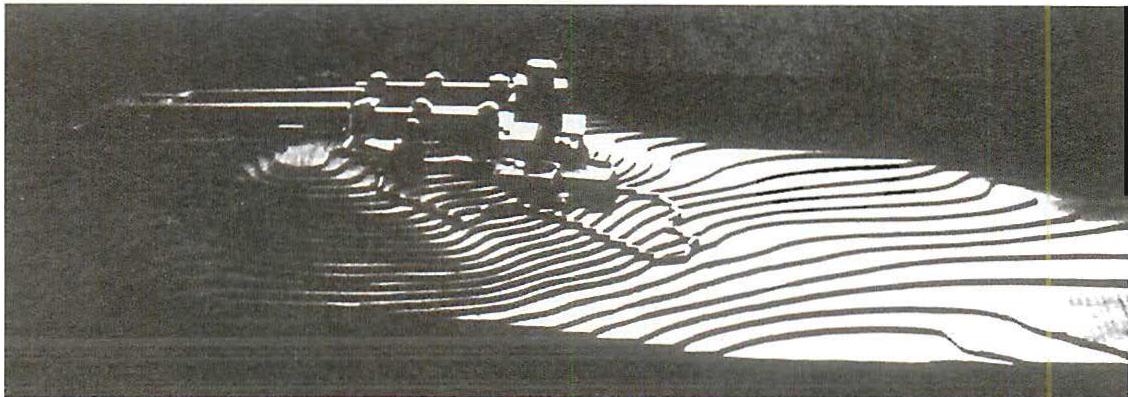

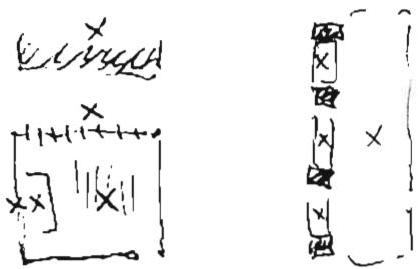

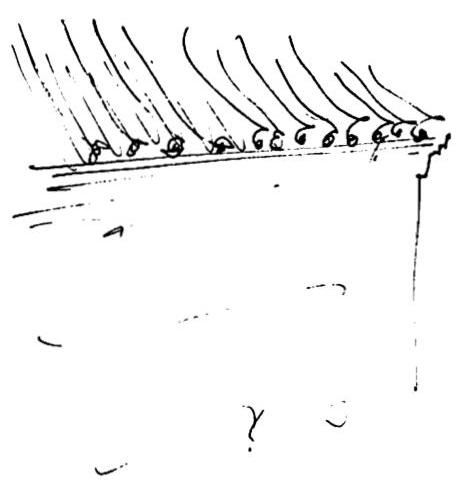

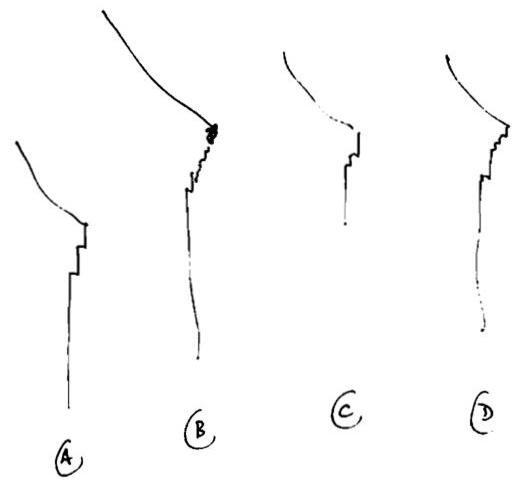

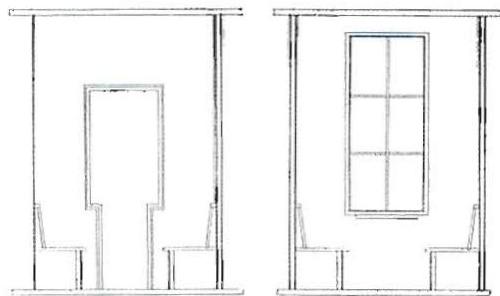

EVOLUTION OF A SET OF DRINKING GLASSES: FOUR STEPS SHOWING A LIFE--CREATING PROCESS EXTENDING OVER A FEW WEEKS

Step 1. A sketch, in which we first tried to identify the main centers of the glass, and to get its resulting form from the general character of these centers. The centers are visible and strongly marked. They form the core of the design: the center of the bowl, of the foot, of the base of the foot, even the ornaments on the glass. All were already roughly defined at this early stage, and serve to accentuate the centered aspect of the form.

Step 2. A series of wooden forms — about 20 — which were turned in my office by my assistant Katalin Bende. Here we tried to find out which of these glasses was most comfortable in the hand, most comfortable in the feeling of its weight, balance, and appearance in three dimensions.

Step 3. A stage in which a single rough glass was blown for us by Dan Reilly in his glass-blowing shop in Oakland. Here we tried to find the glass whose overall feeling, weight, appearance, color, came closest to the impression caught in the wooden molds.

Step 4. A stage in which we made a mold for the glass factory in Leerdam and in which Henk Verweg, the glassblower, blew a number of these glasses to the shapes I asked, using different thickness and layers, and which I then left plain, painted with gold paint, and remade with application of gold leaf (opposite page).

Throughout these steps, I did need to have the reality of centers in my mind while I was working. But I did not have to talk to myself in the jargon of centers to be successful. What actually happens in detail, in different projects, is unendingly varied. I hope that will be clear from the examples in this book.

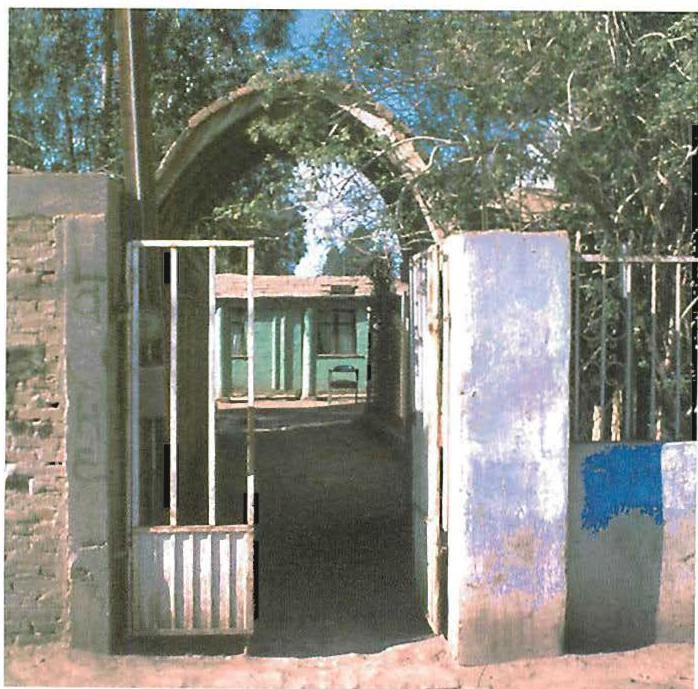

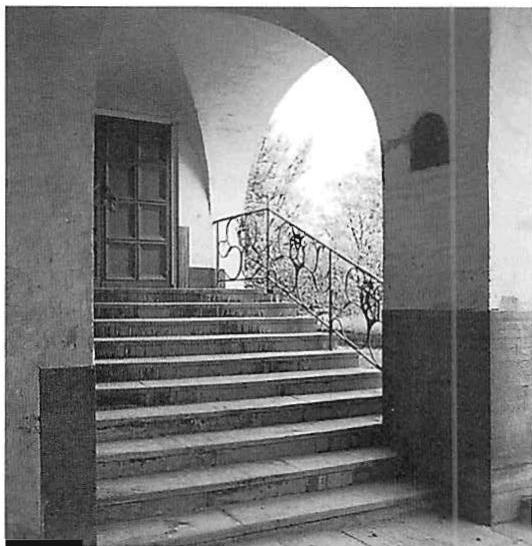

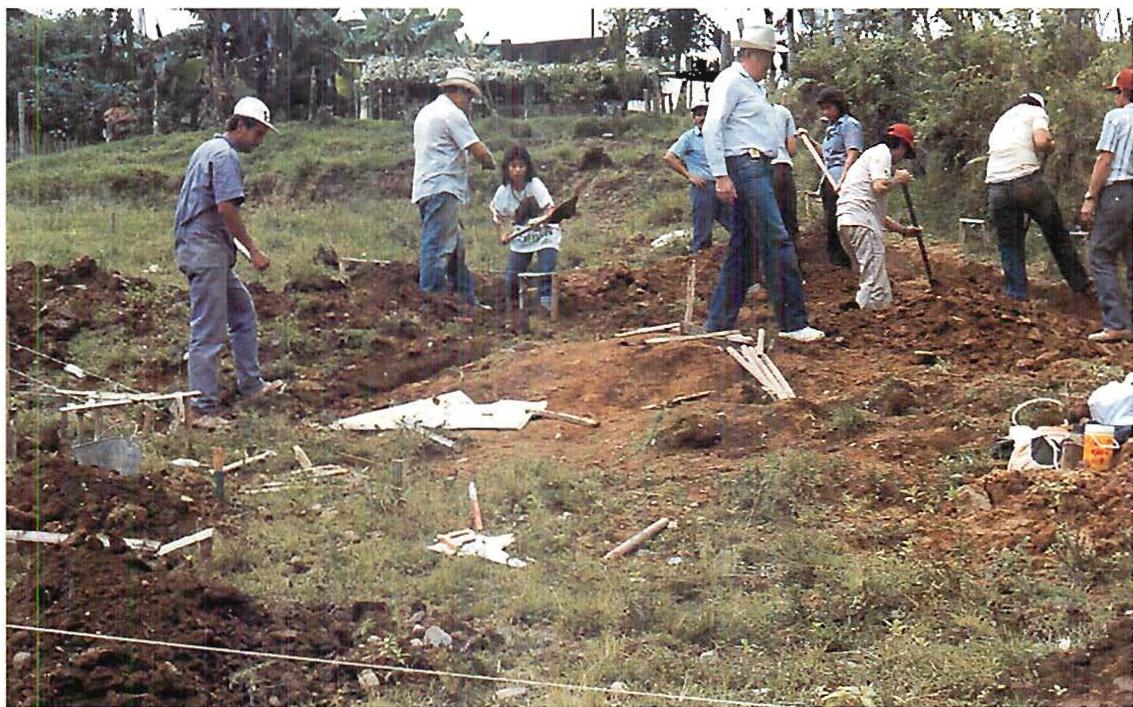

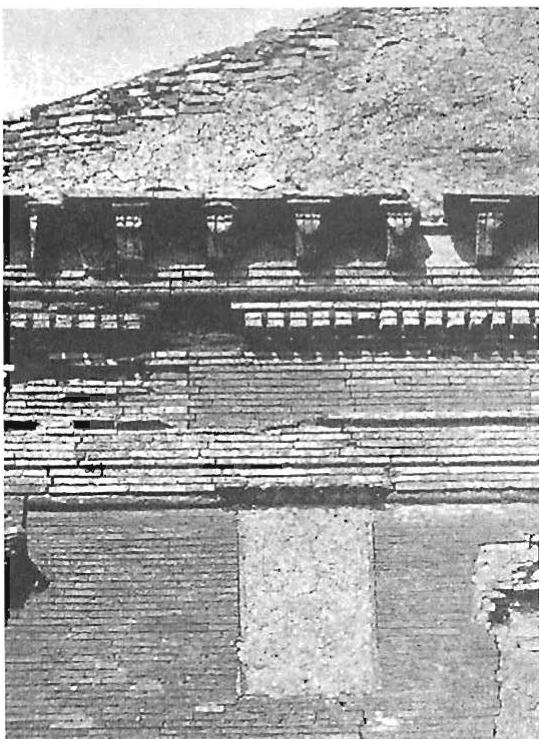

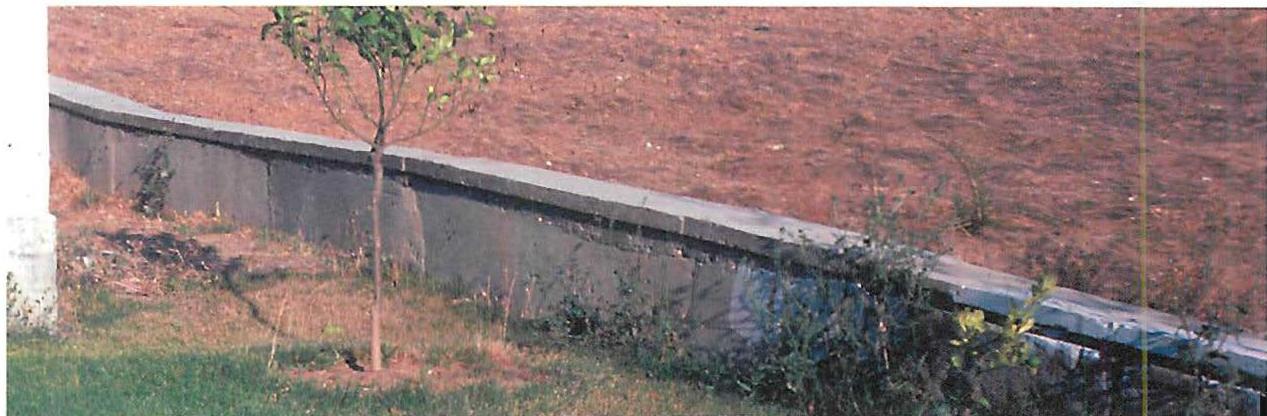

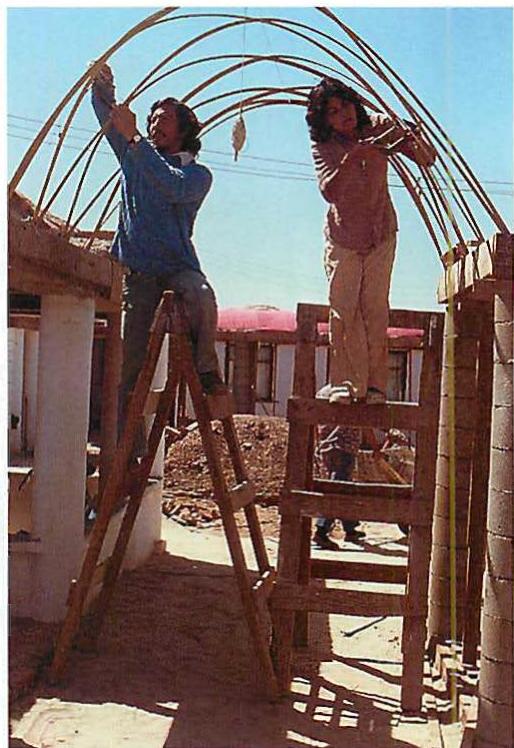

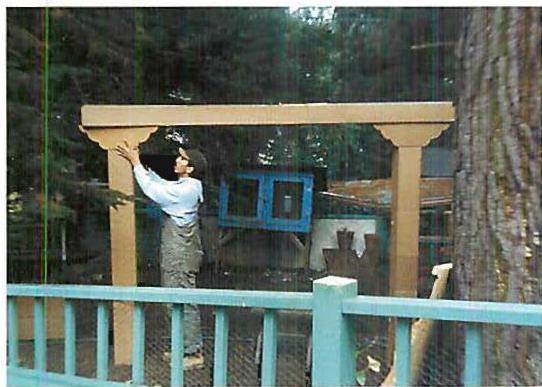

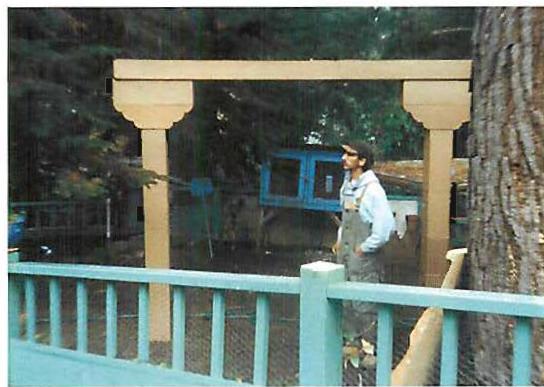

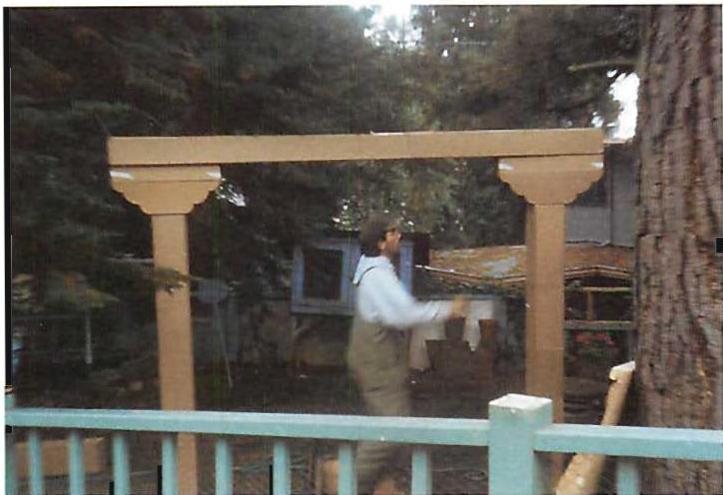

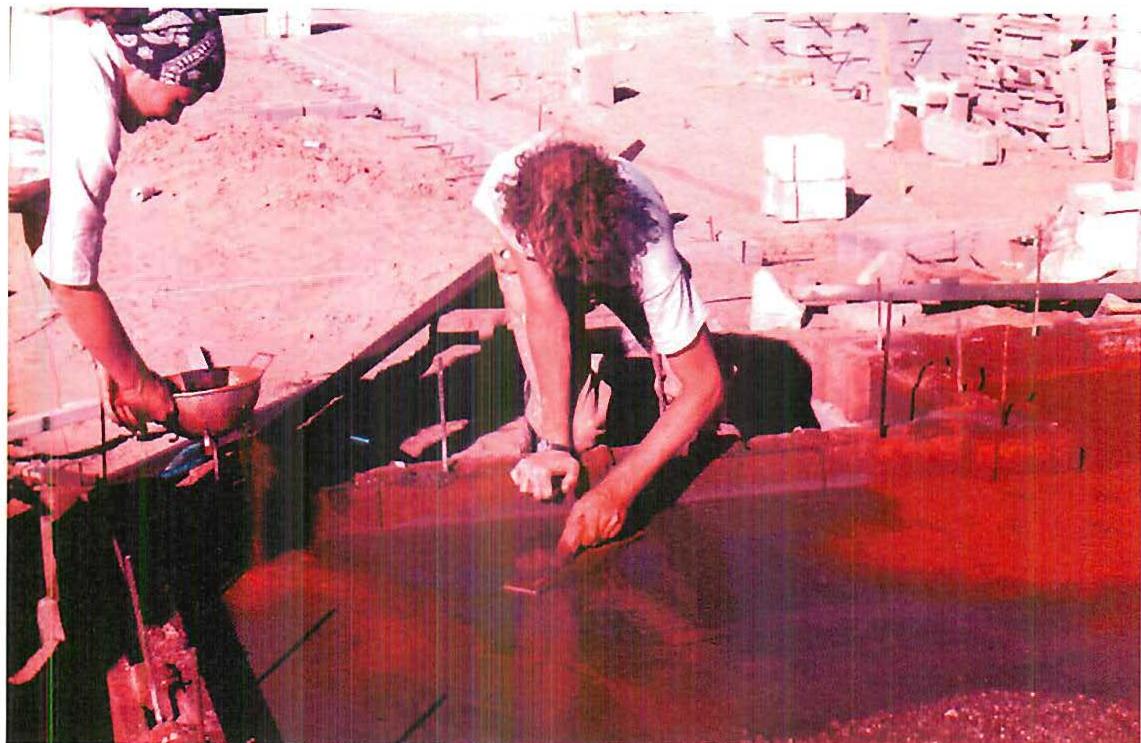

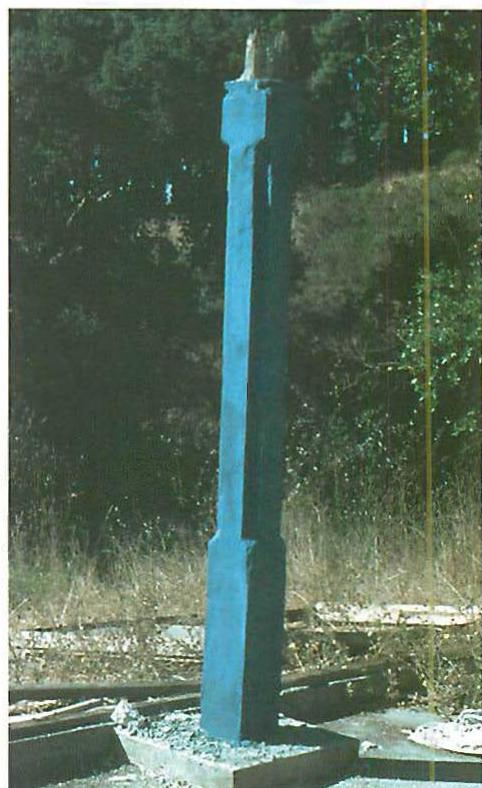

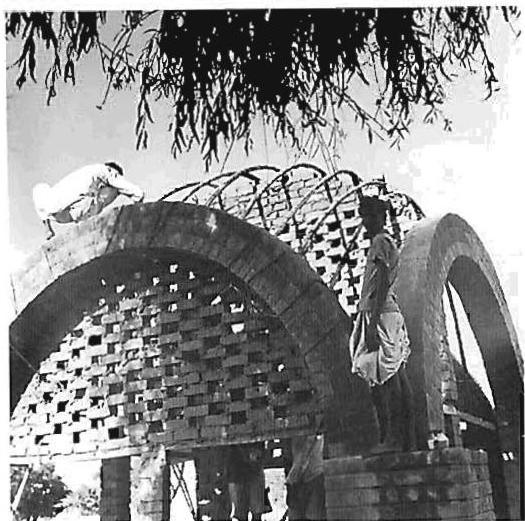

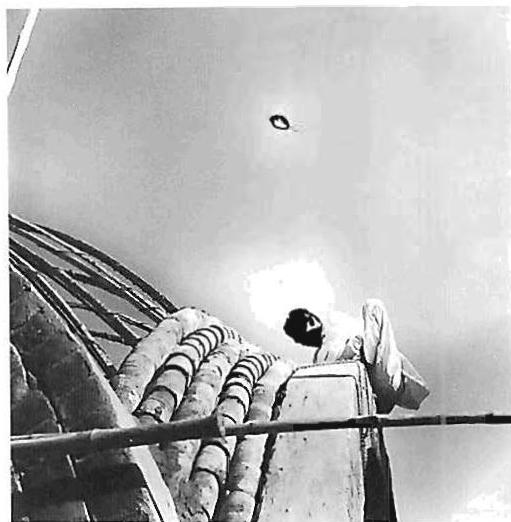

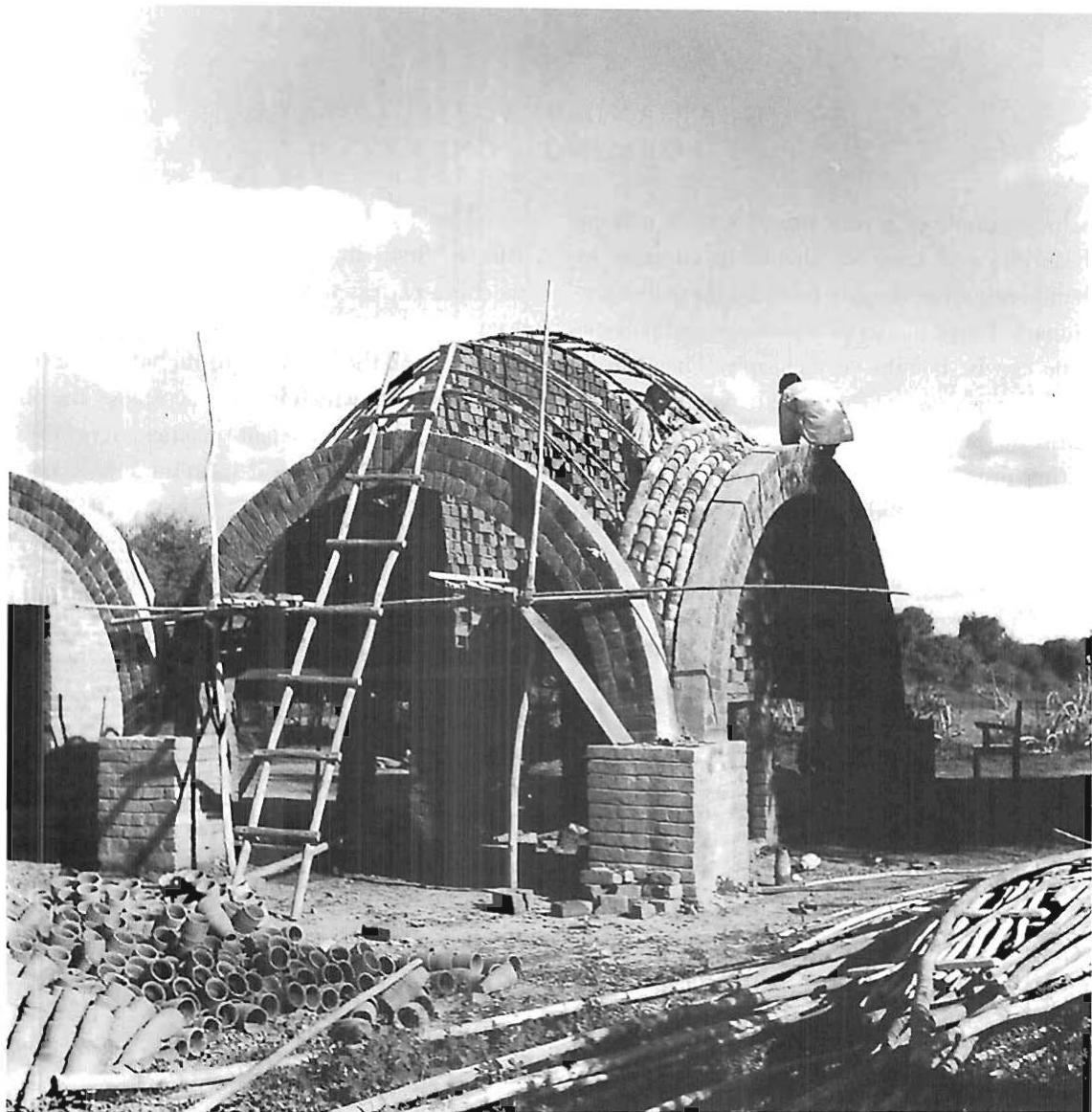

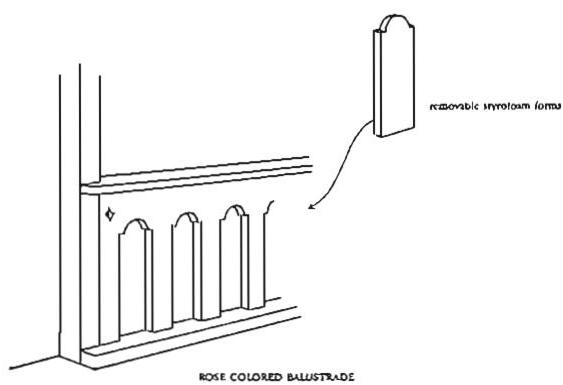

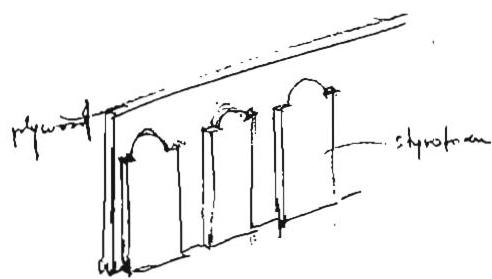

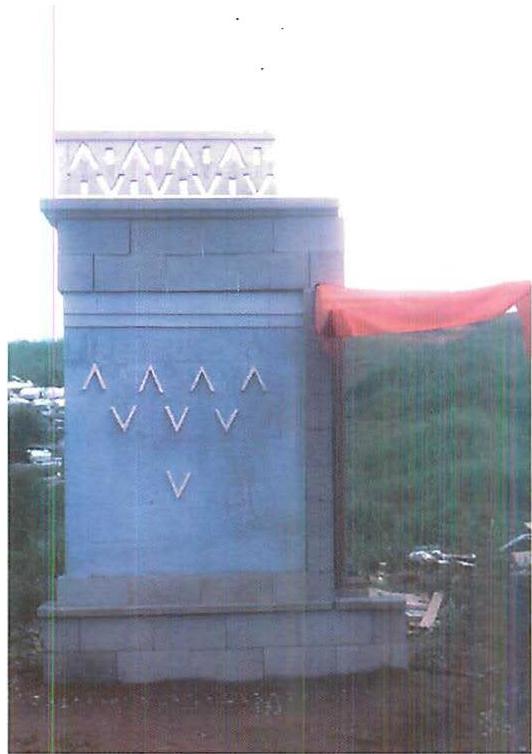

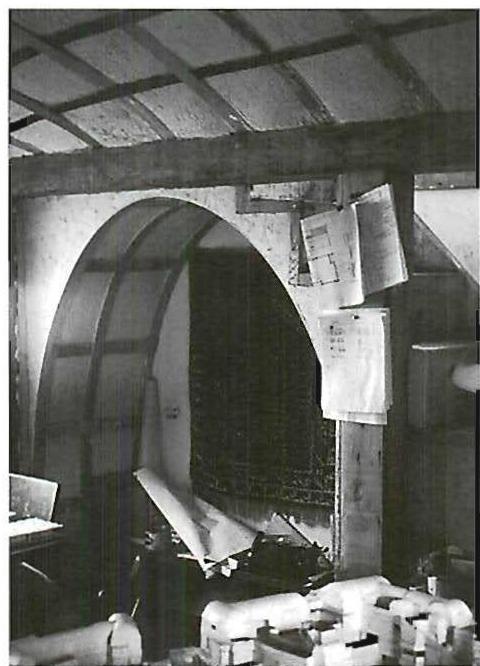

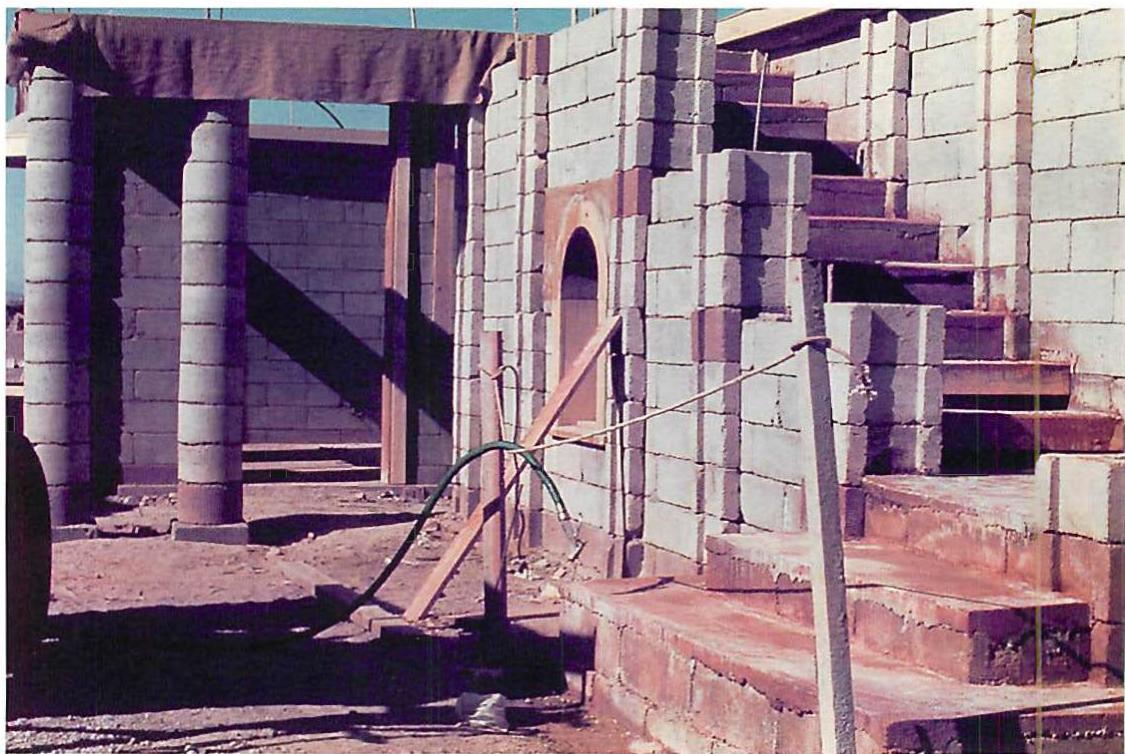

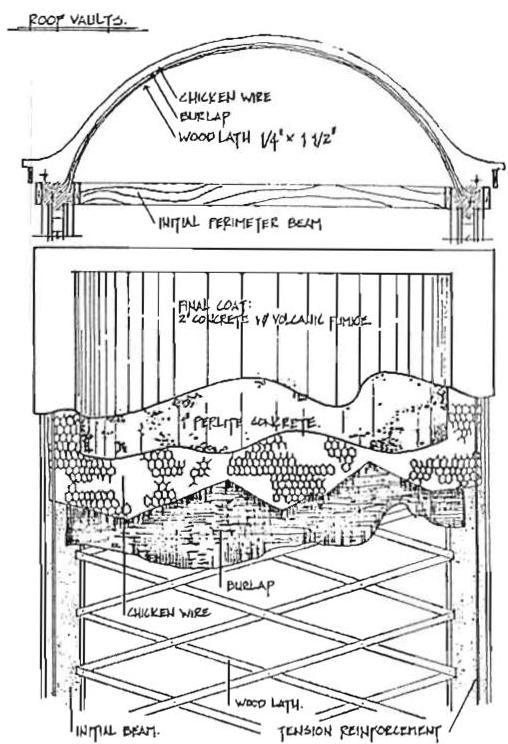

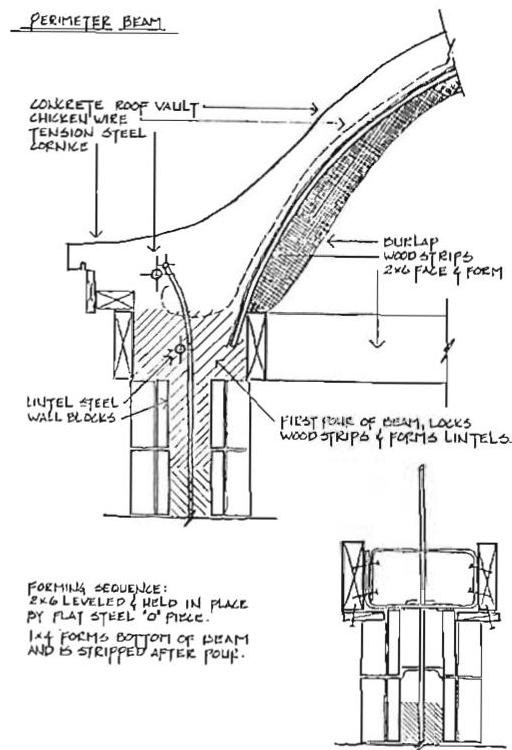

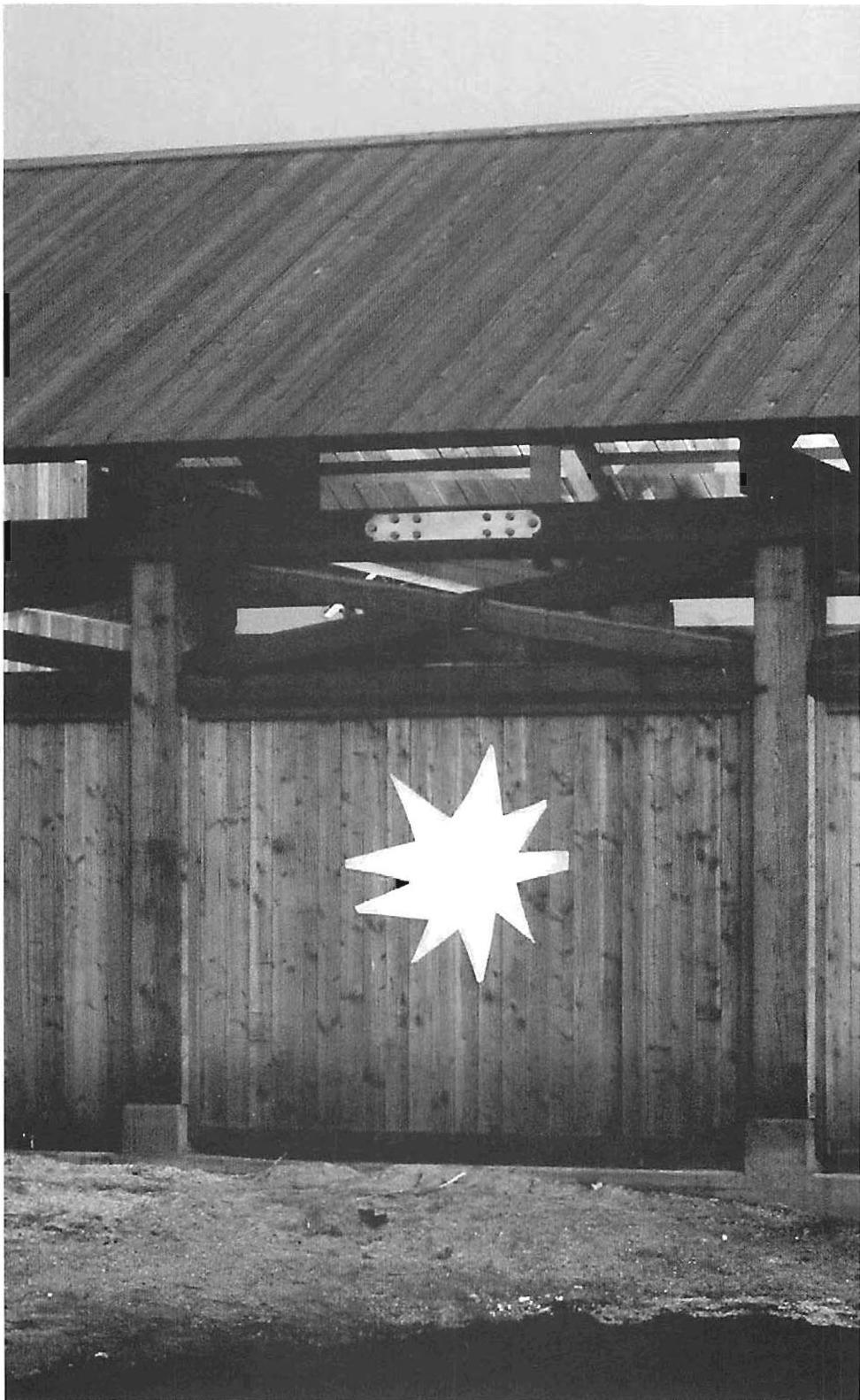

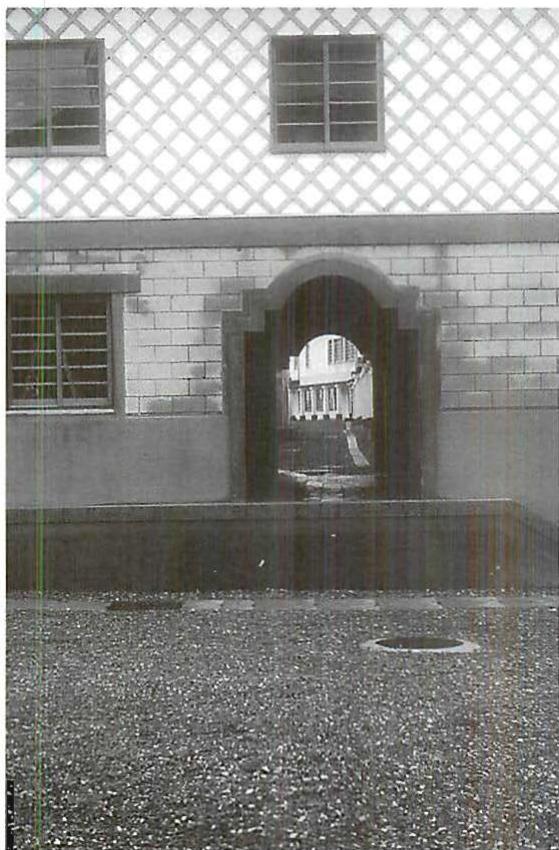

CONSTRUCTION OF A GATEWAY LEADING TO FIVE LOW-COST HOUSES IN MEXICO: ANOTHER SMALL EXAMPLE OF A LIVING PROCESS

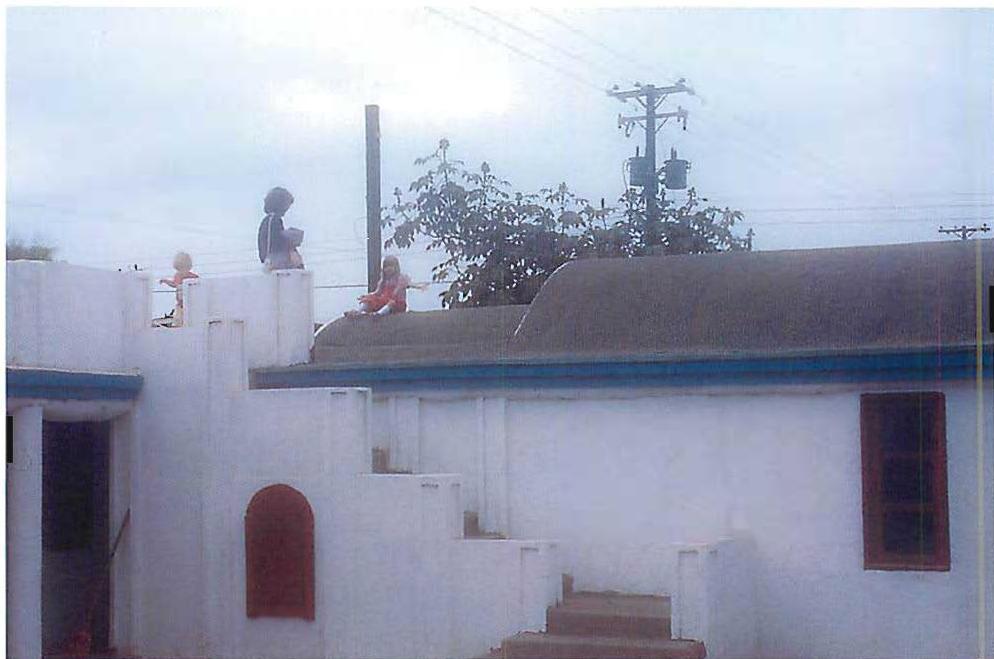

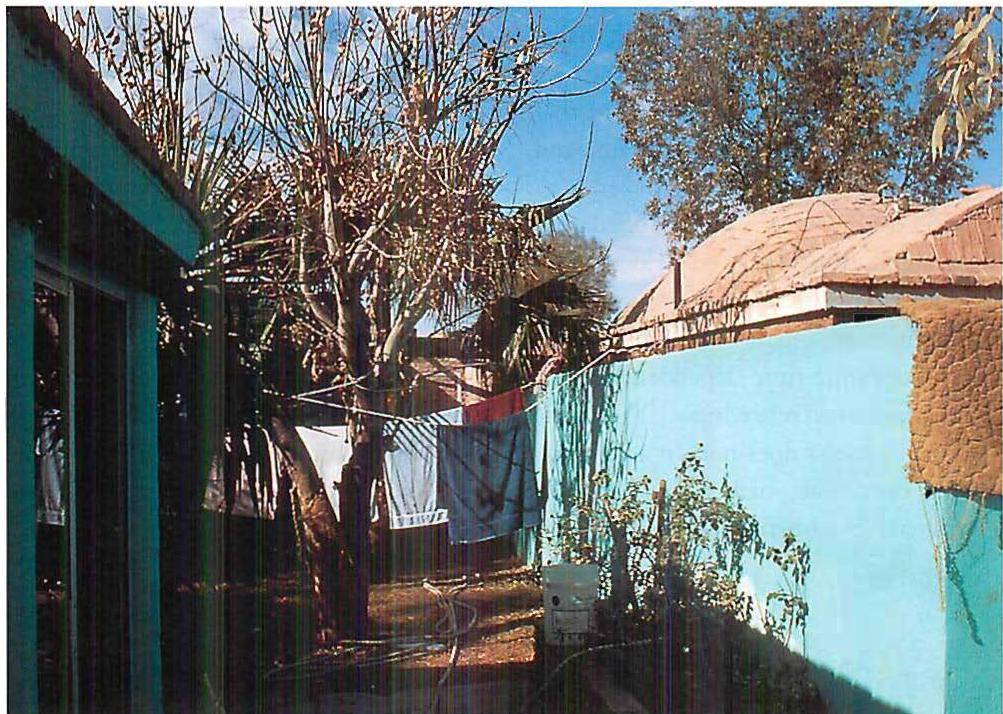

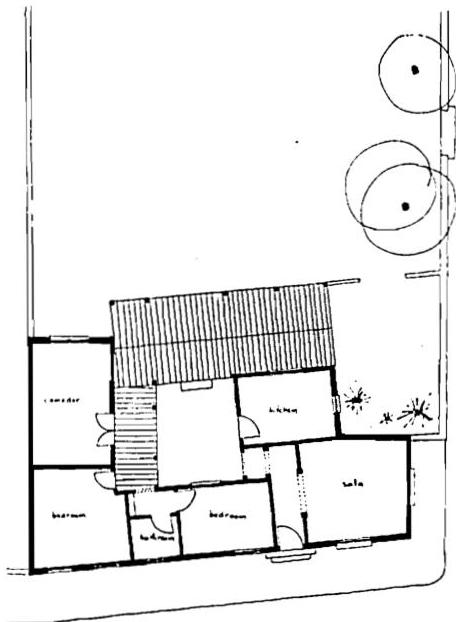

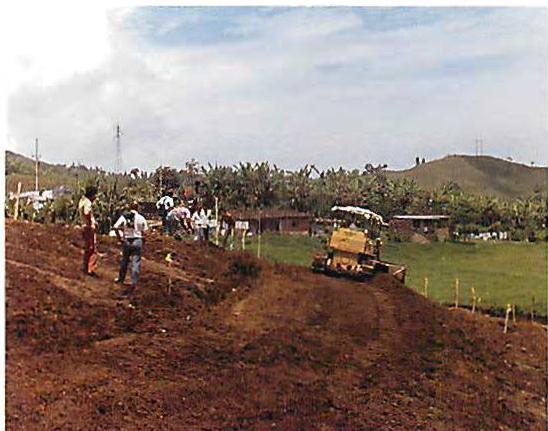

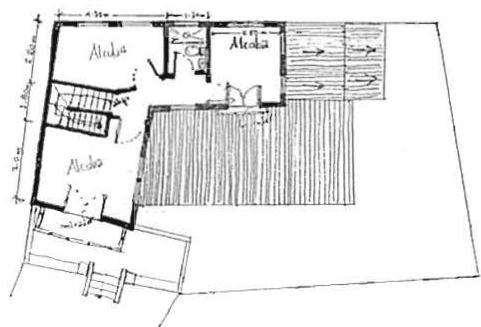

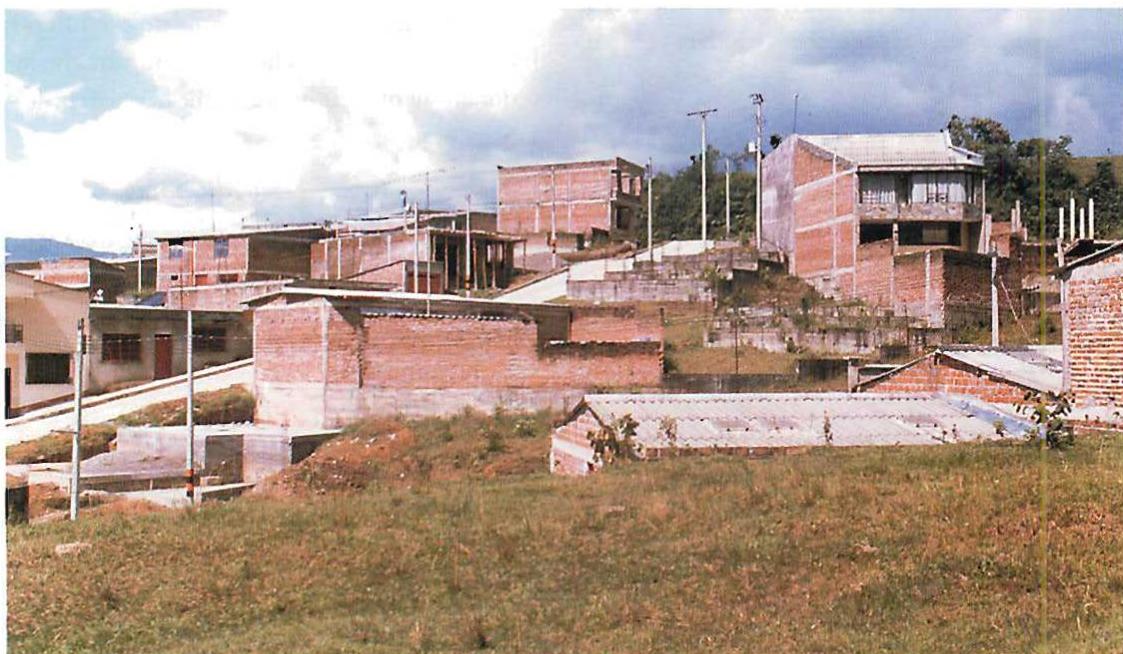

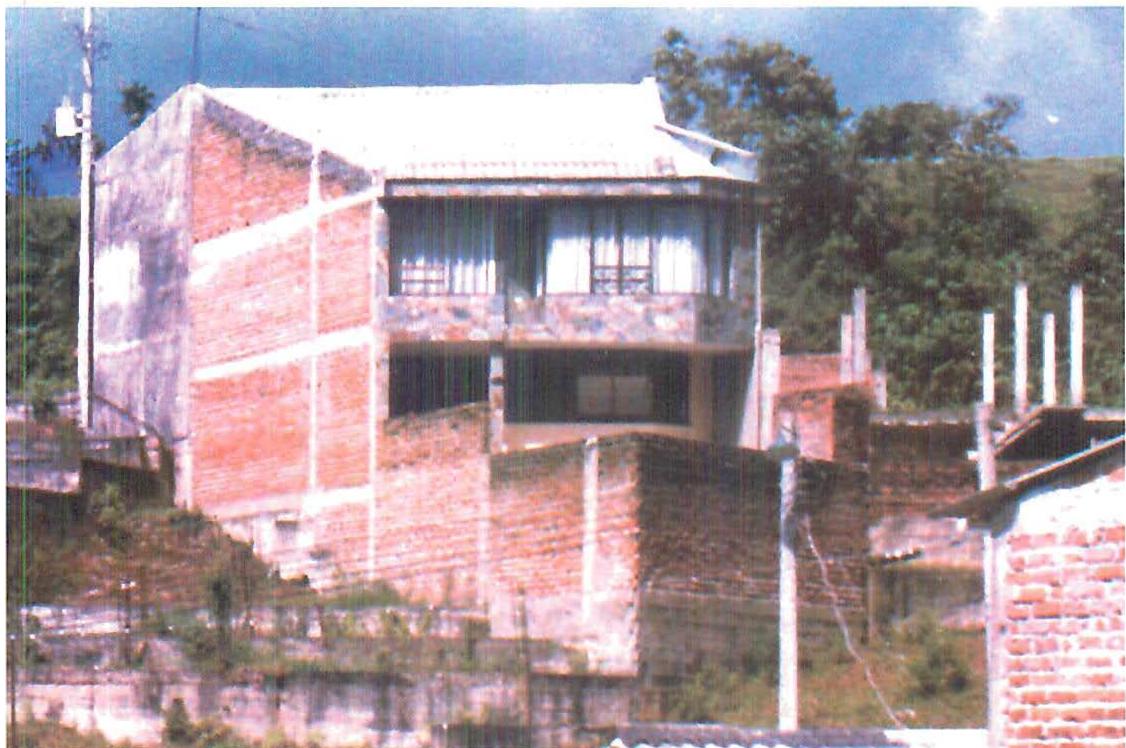

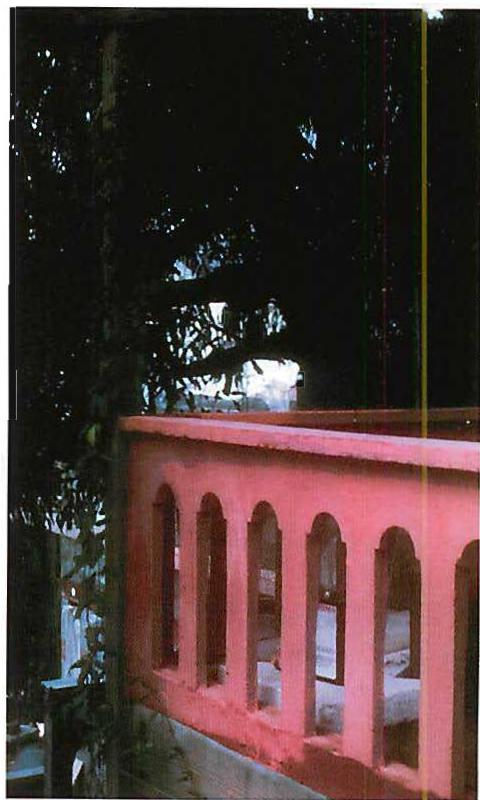

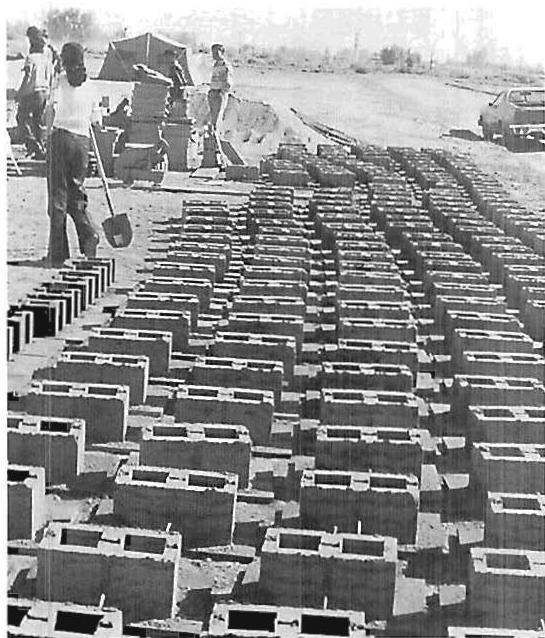

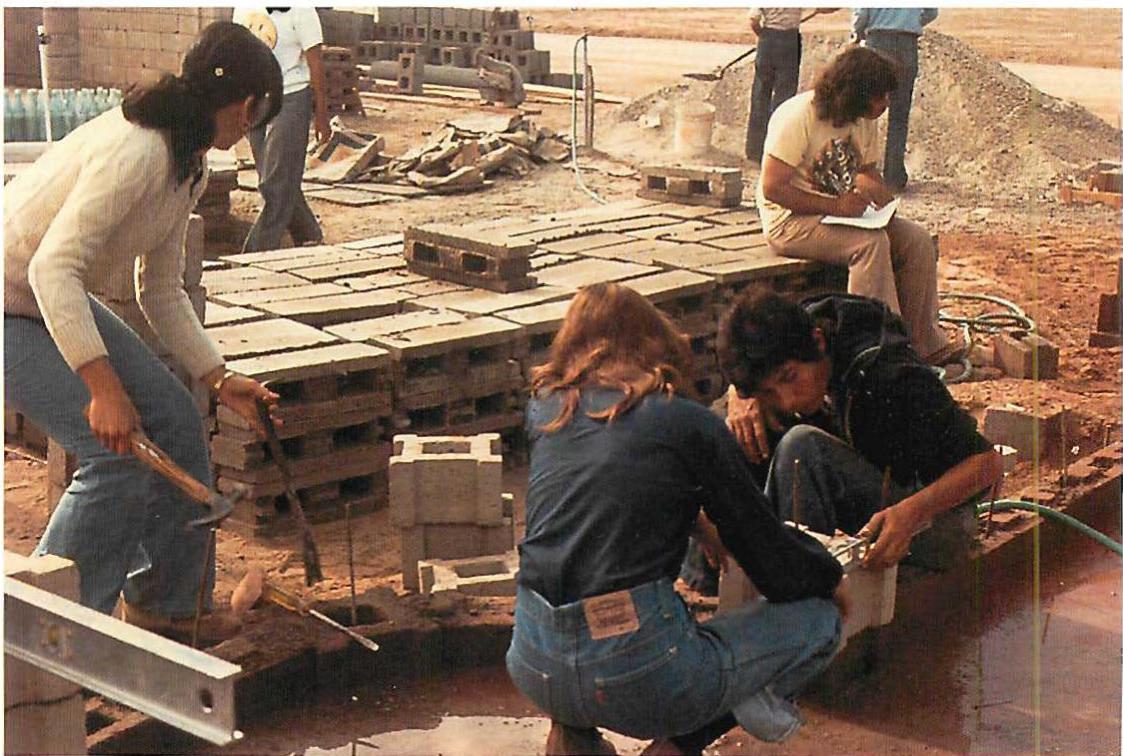

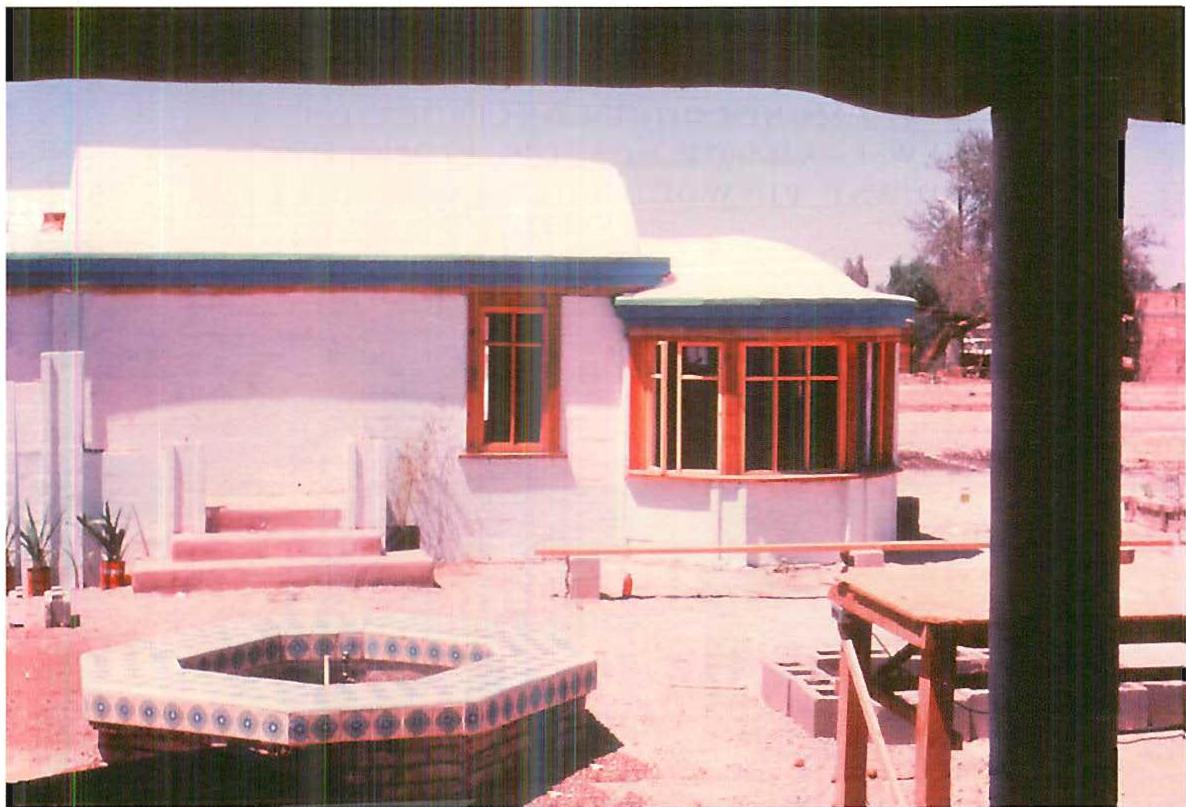

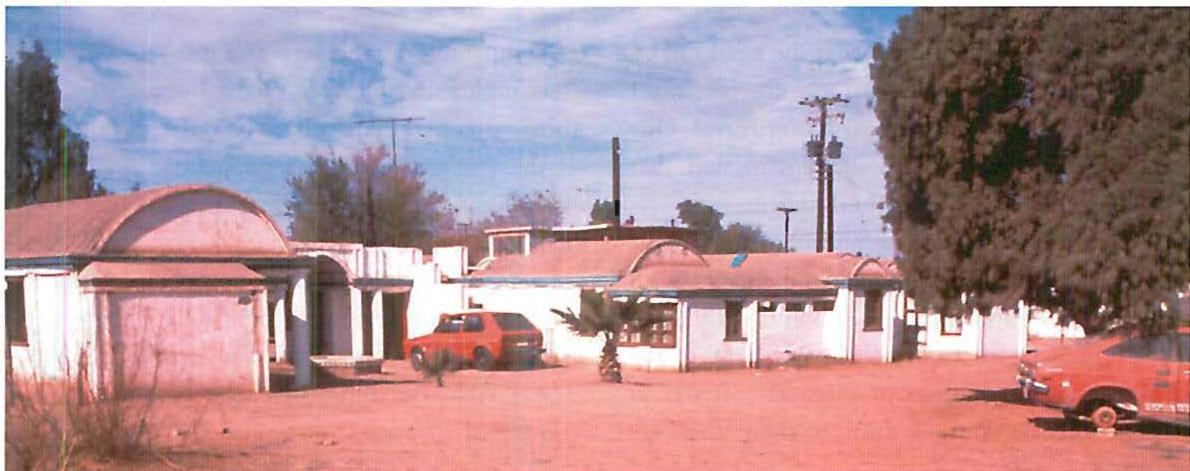

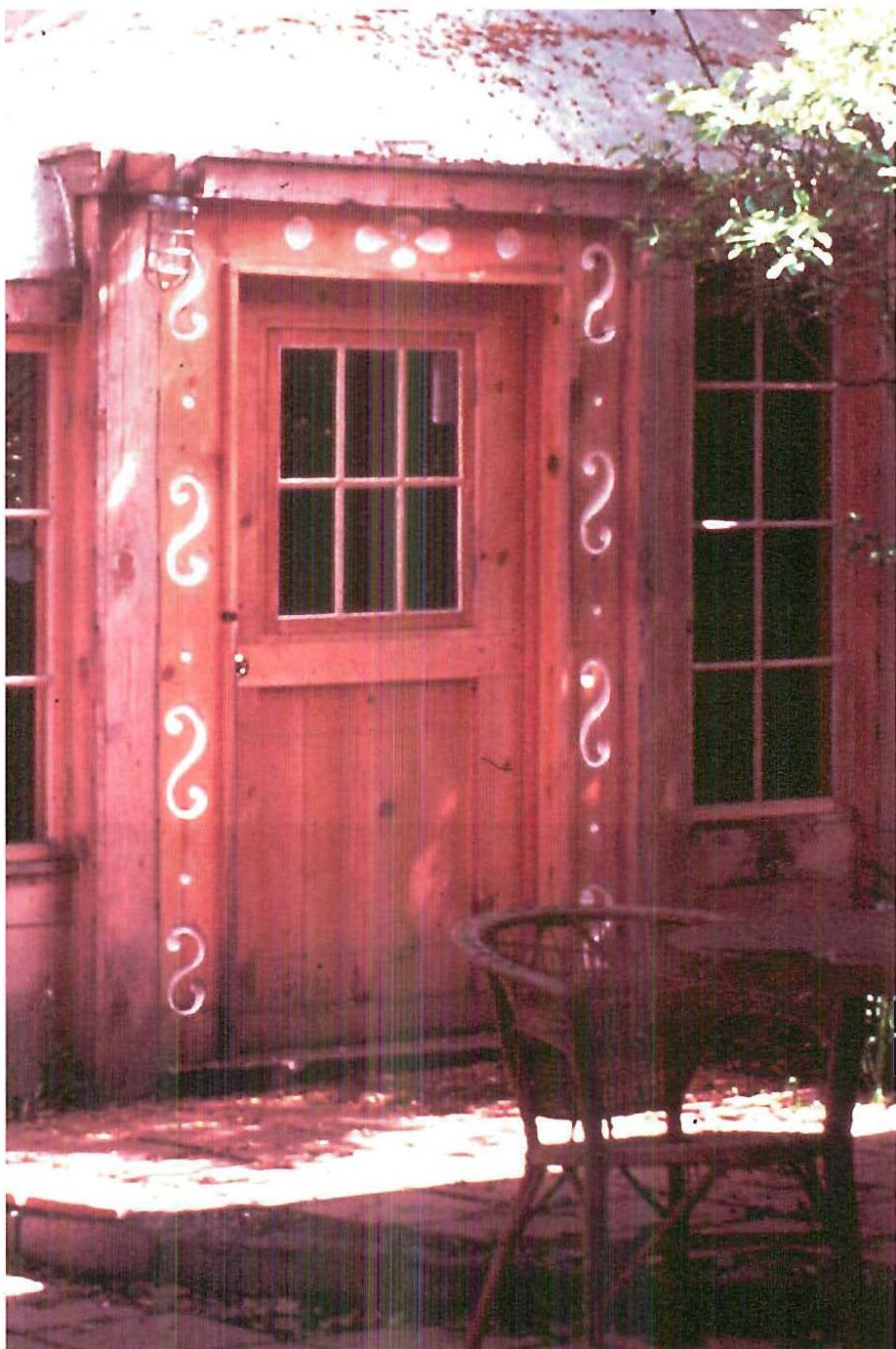

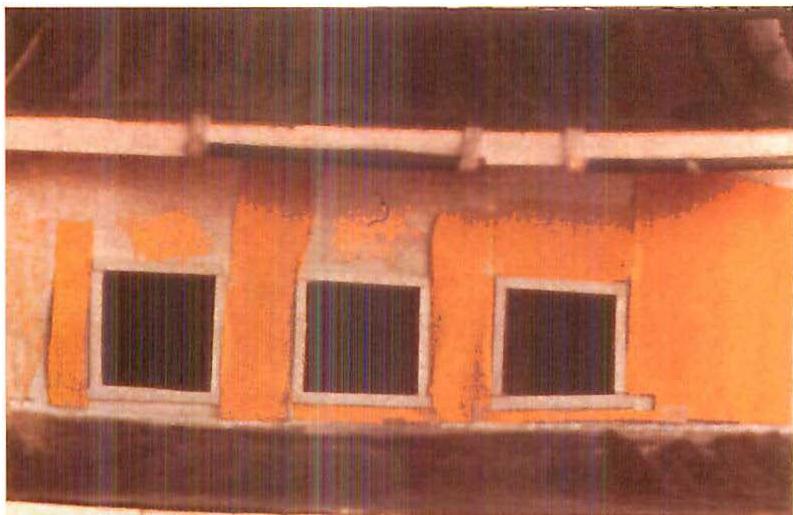

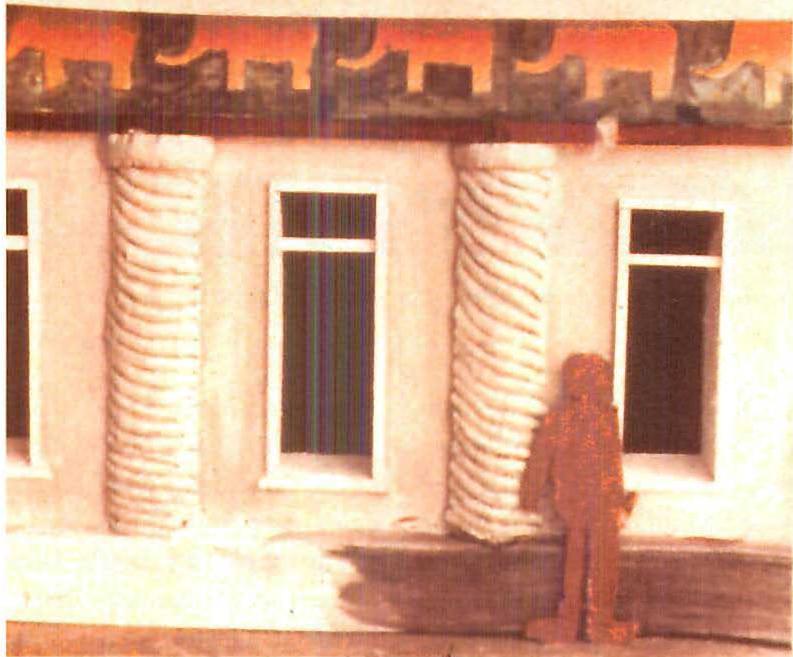

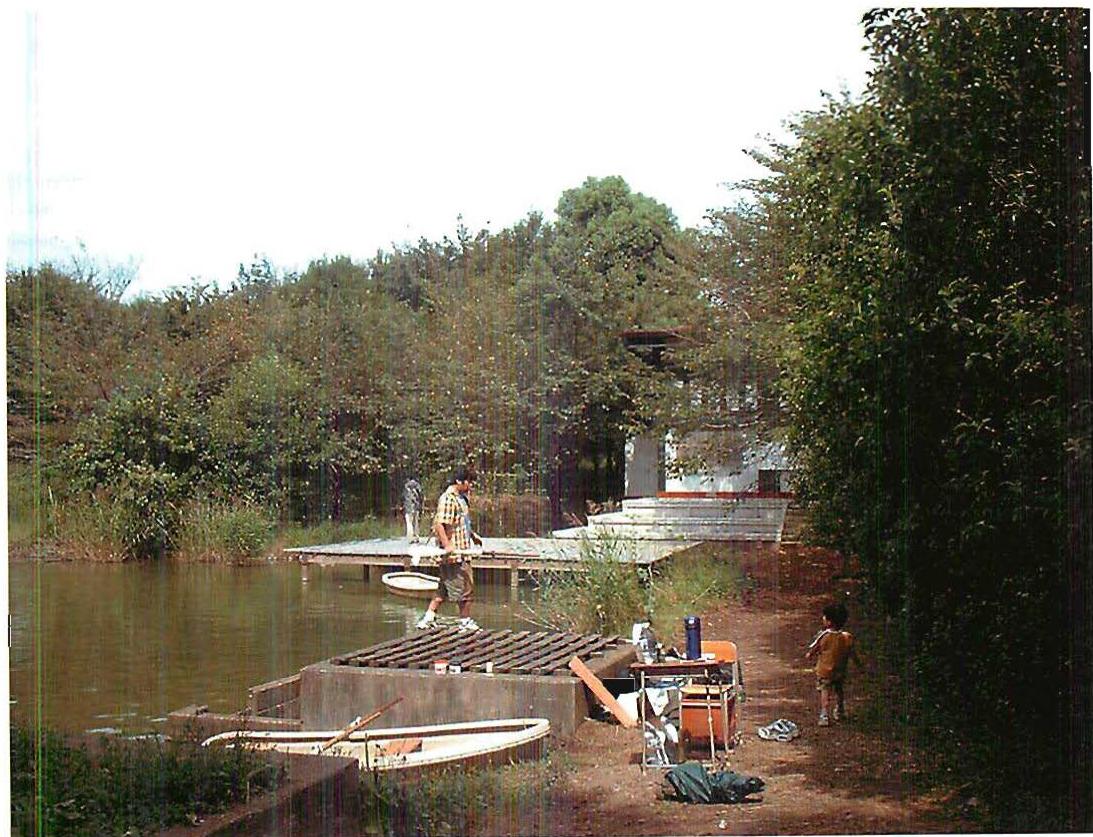

In another instance, an ultra-low-cost housing project where people built houses for themselves, with our help. Cost, $3,500 per house. When we were finished, I encouraged the users to use living processes to build further components of the project, as we had built the houses with them, using living process, paying attention to their feelings, and the way the centers helped support their feelings. They built gates, extensions to the houses, gardens, porches, a barbershop.

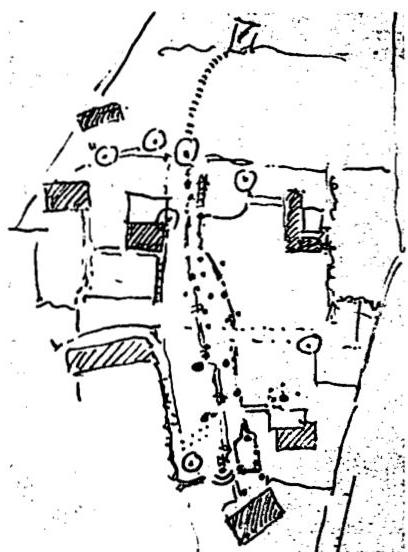

One gate they built during this later period is shown below. The families and amateur builders themselves made this rudimentary gateway. Here again, in a modest, even crude form, still the process kept on creating living centers. Crude as it is, we see living centers in the symmetry of the arch, in the ironwork of the gate, in the weight of the big column on the right as a result of their effort to form a boundary there. Because of these touches, the place has life. It may be crude, dirty, but at least for the time being such is the lot of many people. And it does have undeniable feeling—very different from a developer-built project (for all its mechanical cleanliness), much nicer, much closer to the heart. This came about, I believe, because making the gateway they used, more or less, the following simple sequence, and kept their own wishes and their feelings in mind throughout.

- First, after locating the lots and house positions, they chose the POSITION of this gateway.

- It is locally symmetric and leads to the middle of the common land.

- The width and height of the gateway were determined, again making the gate itself symmetrical.

- The family members then decided its chair

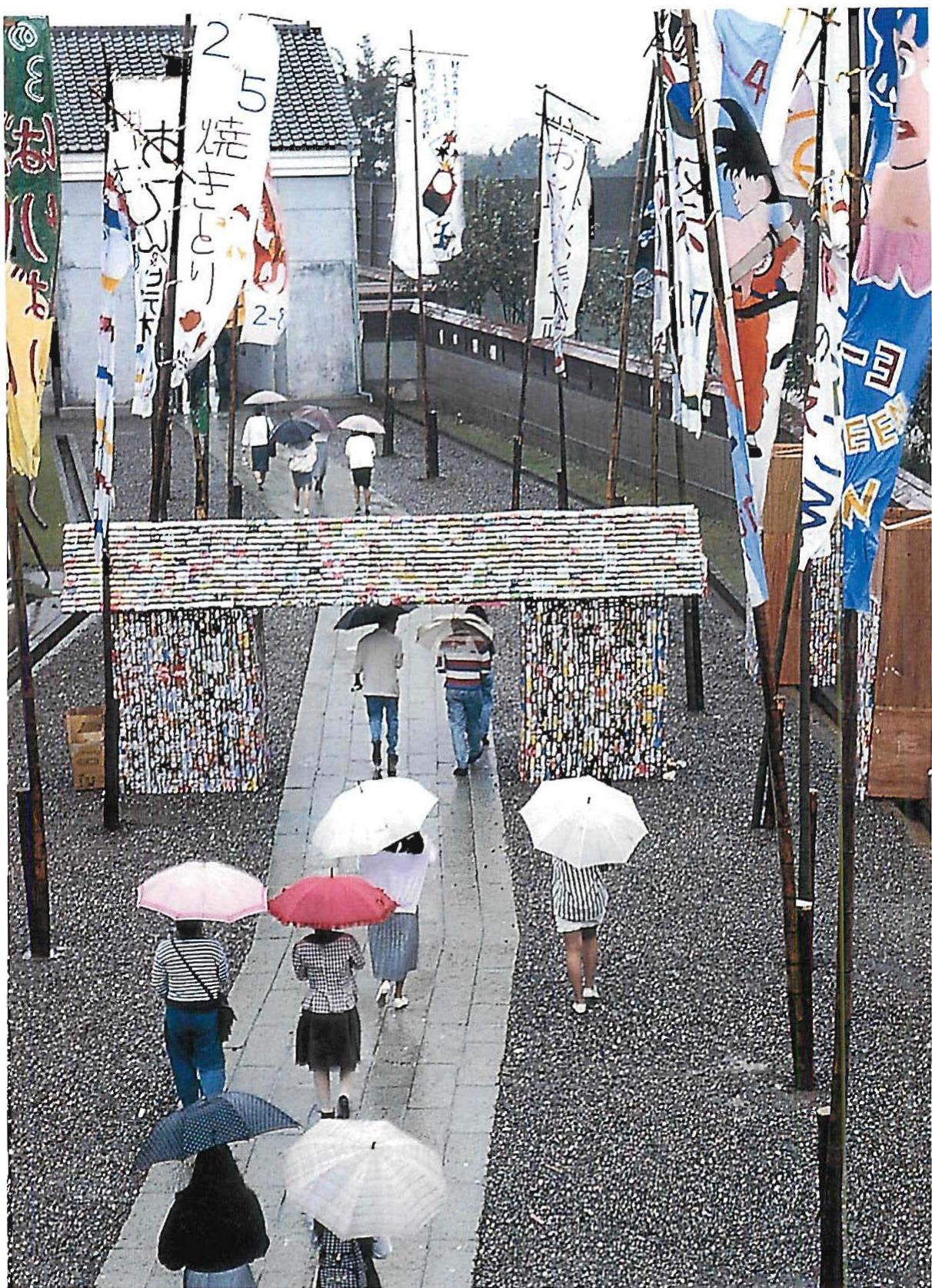

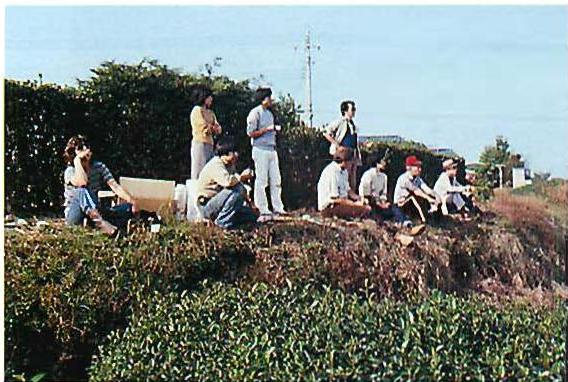

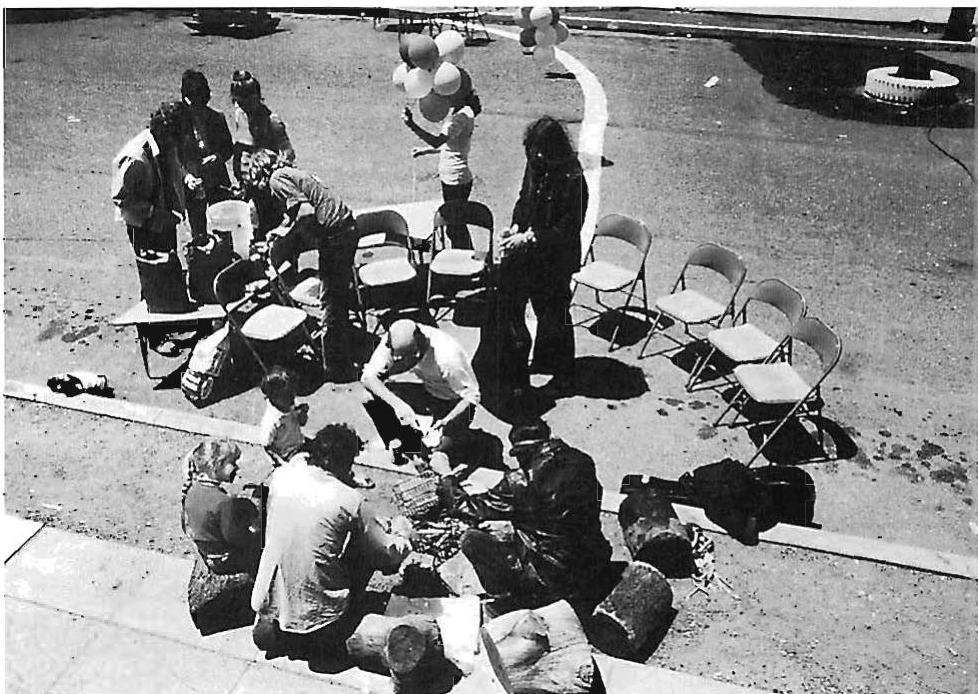

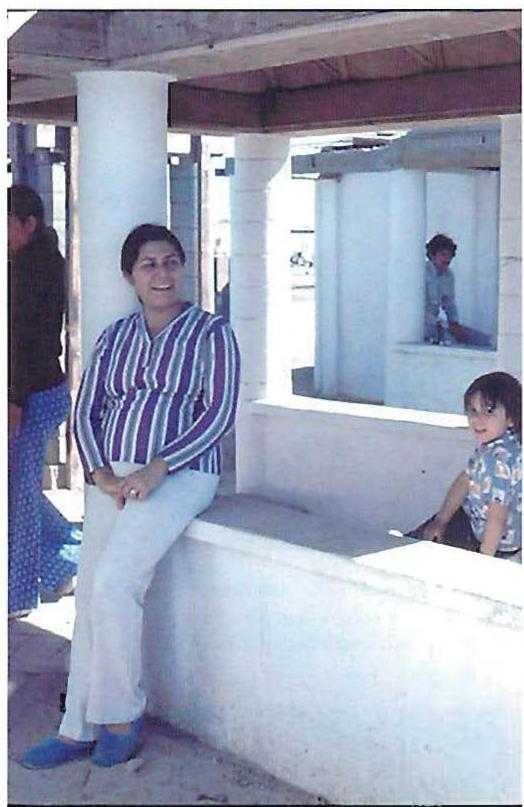

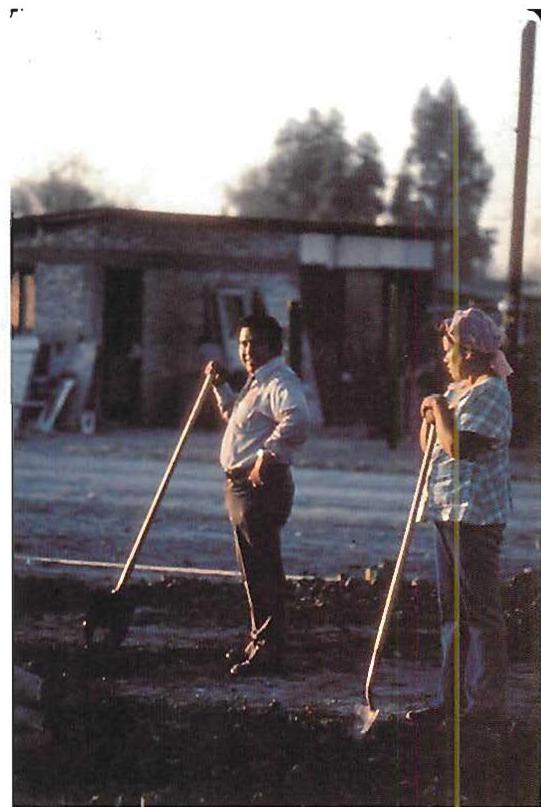

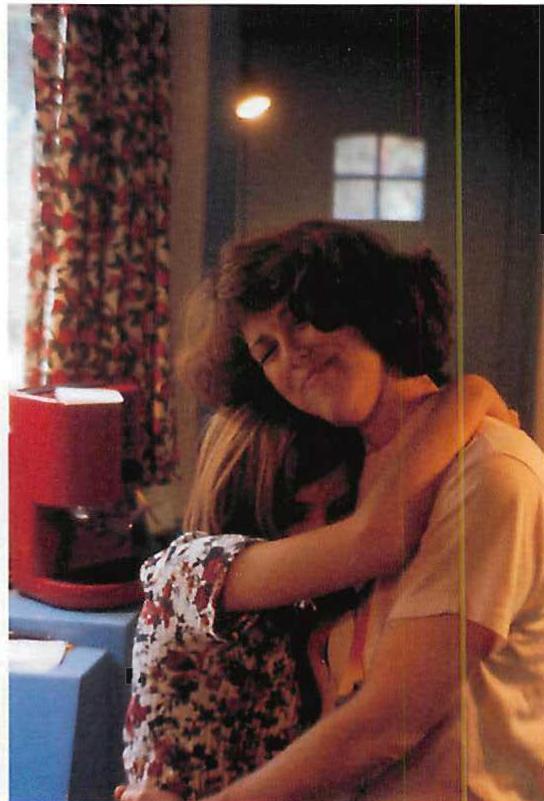

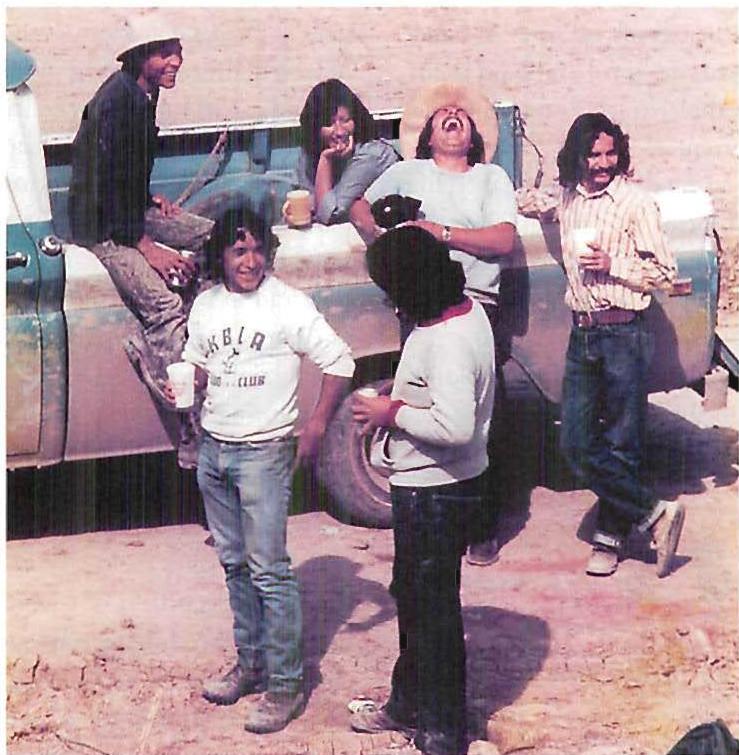

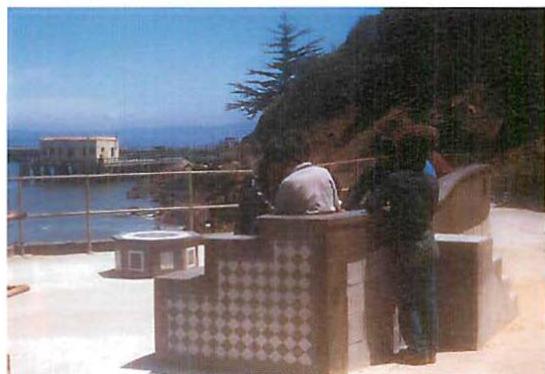

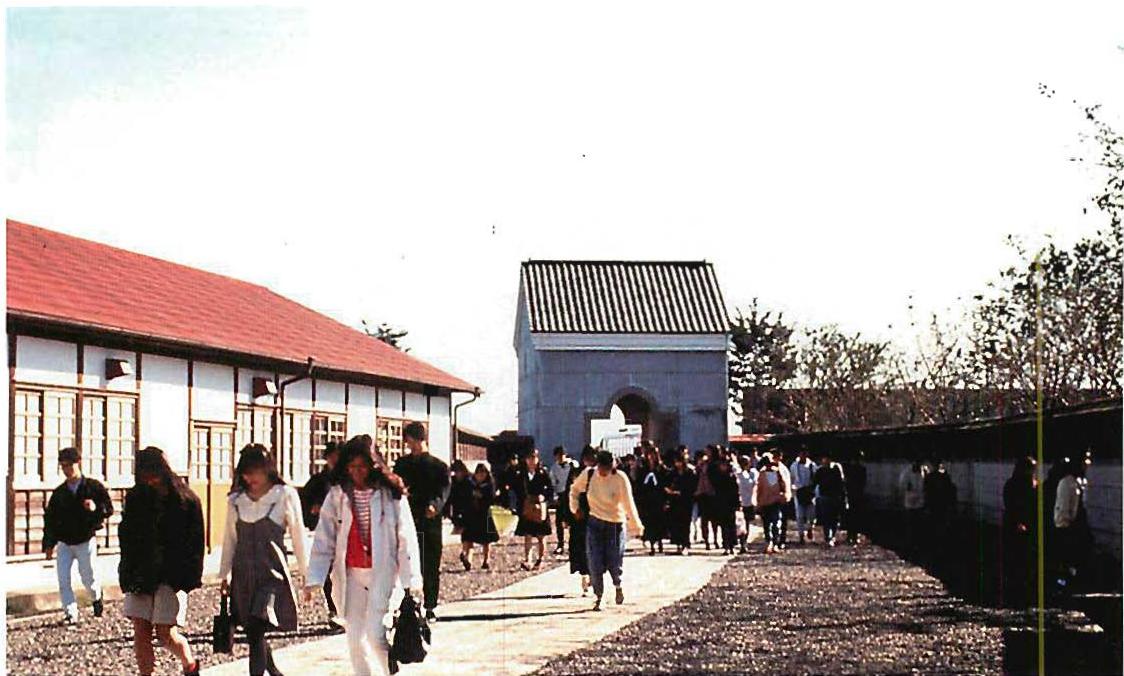

One very ordinary gateway to a small housing project I built in Mexicali, Mexico, 1938. The families, laying out and building their own houses, followed an approximation of the fundamental process. This picture shows the gateway to the five houses, twenty years after the houses were built and occupied, still splendid, in a world where people are very poor. The same five families are still living there. The right-hand picture shows a celebration at the inauguration of the project, when it was first occupied.

acter, height and width. Students who had worked earlier on the project helped the families to build the gateway.

- Next, columns were built in positions to form a positive space within the gateway itself.

- Then beams were built over the columns,

each beam symmetrical in itself, and a roughly symmetrical vault was woven over the entrance and plastered.

- As years went by, the gateway was painted, patched, and modified by the way the families used the place.

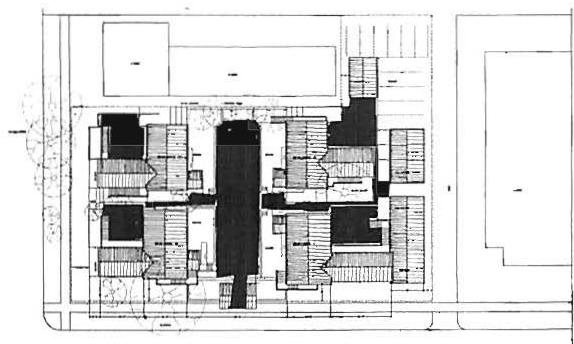

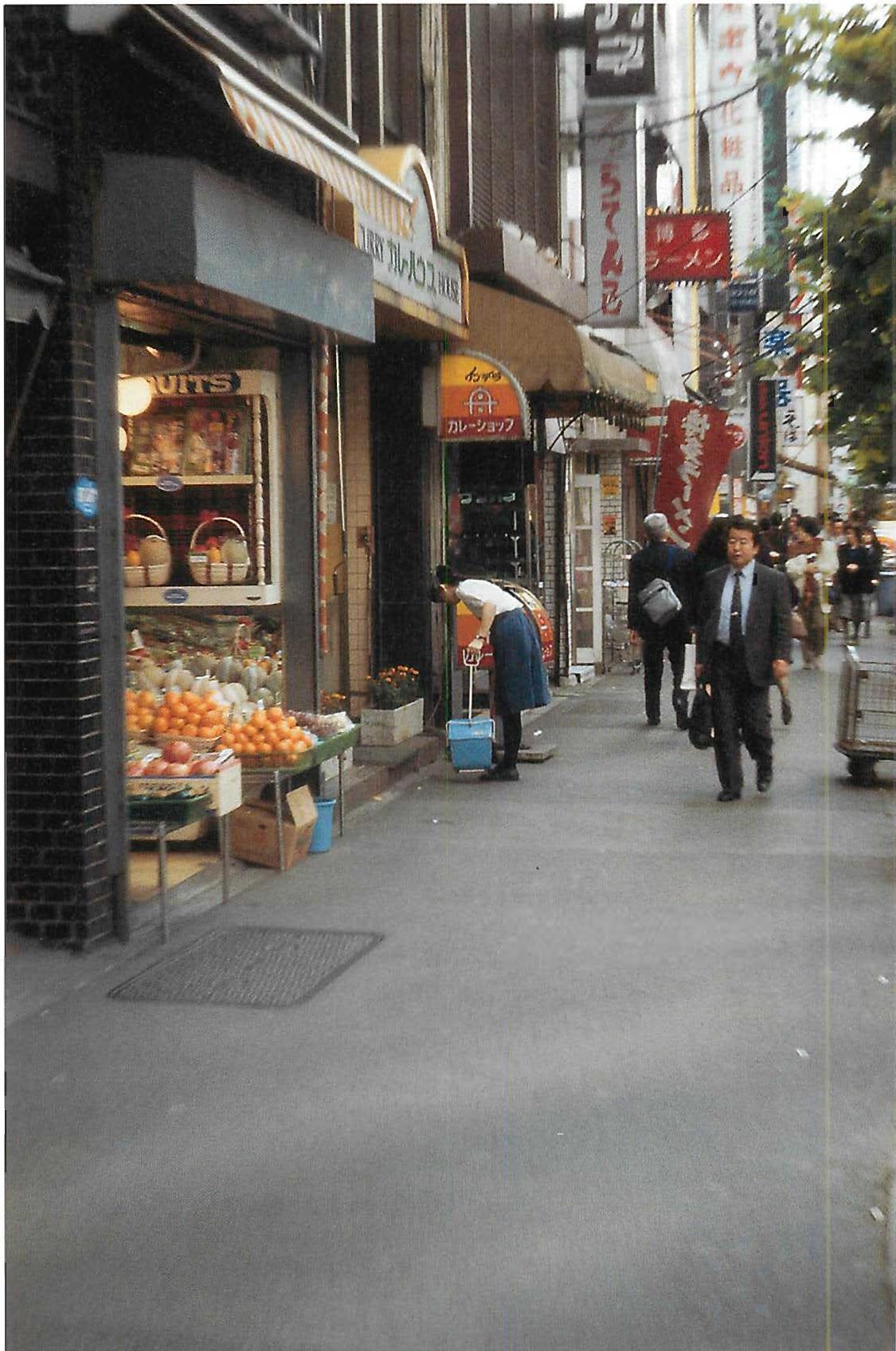

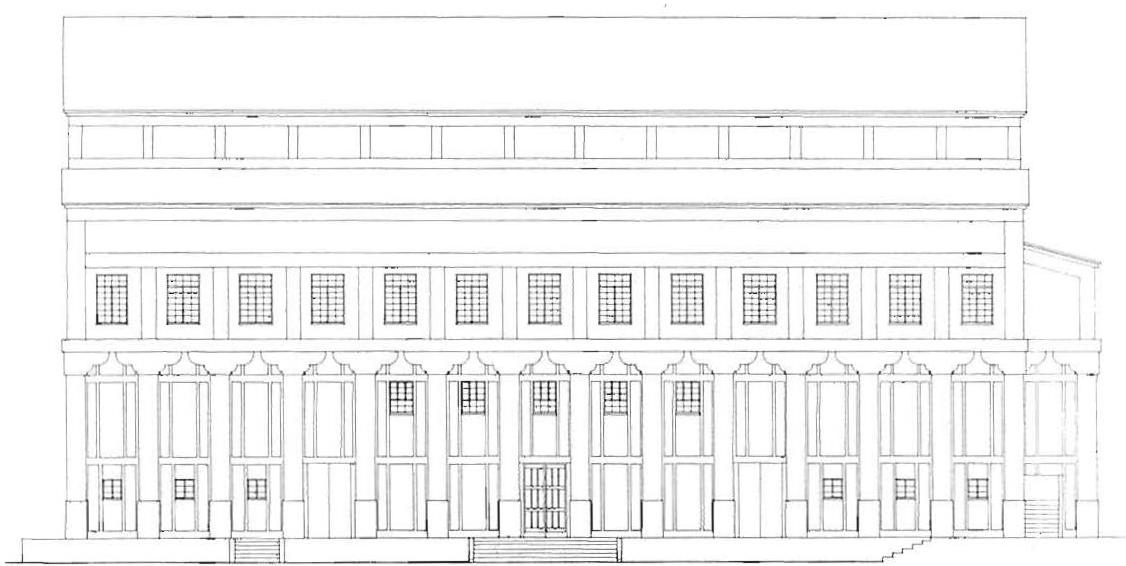

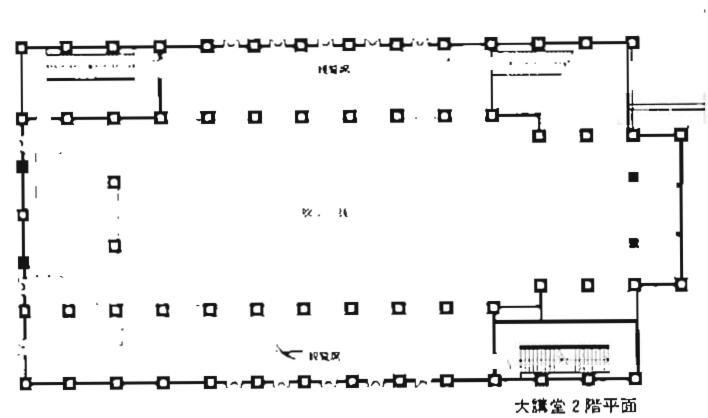

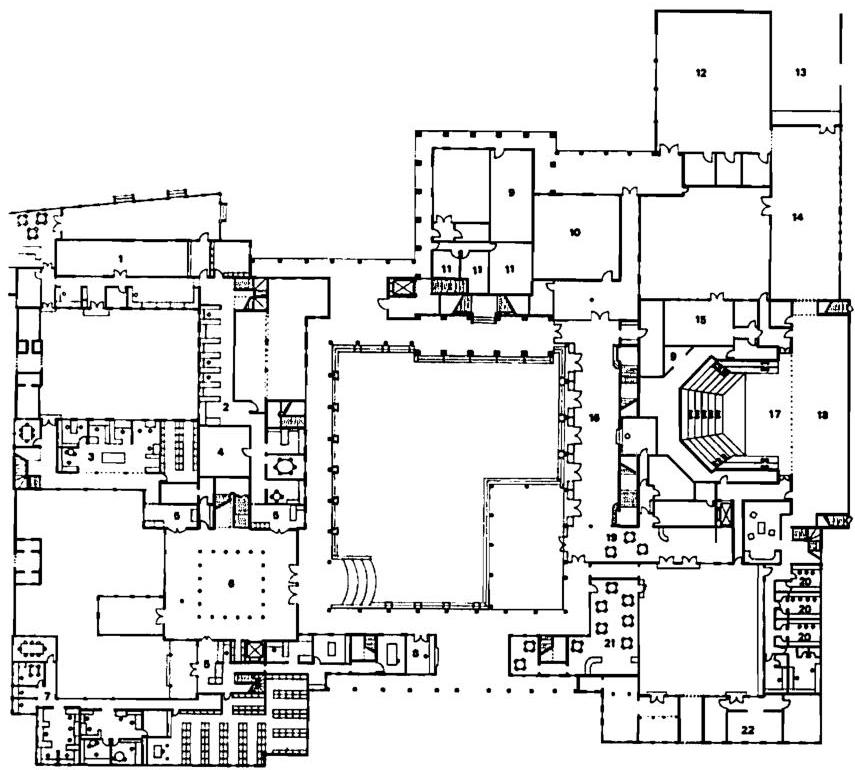

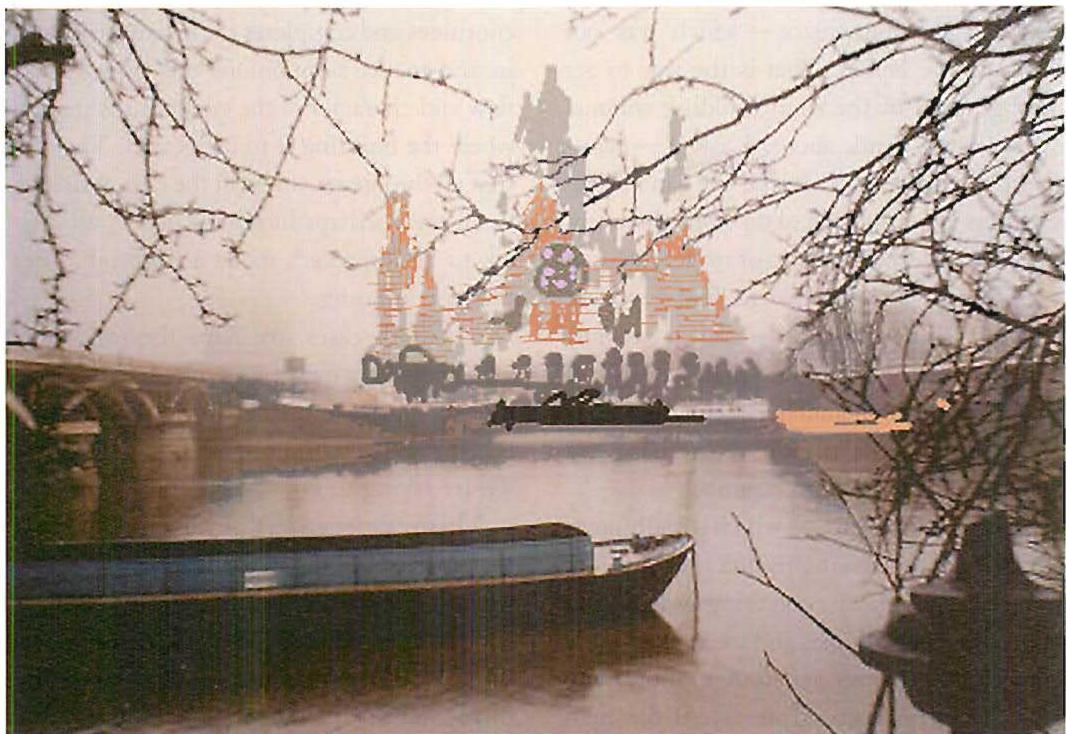

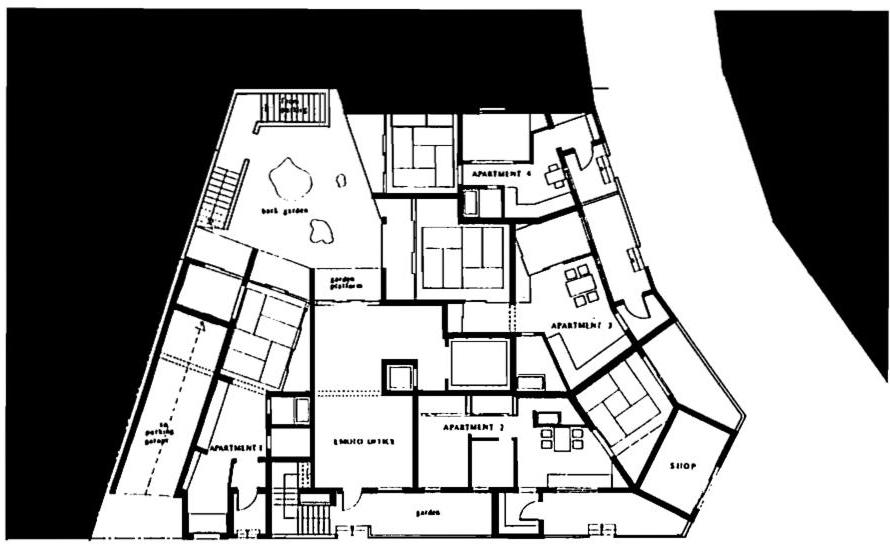

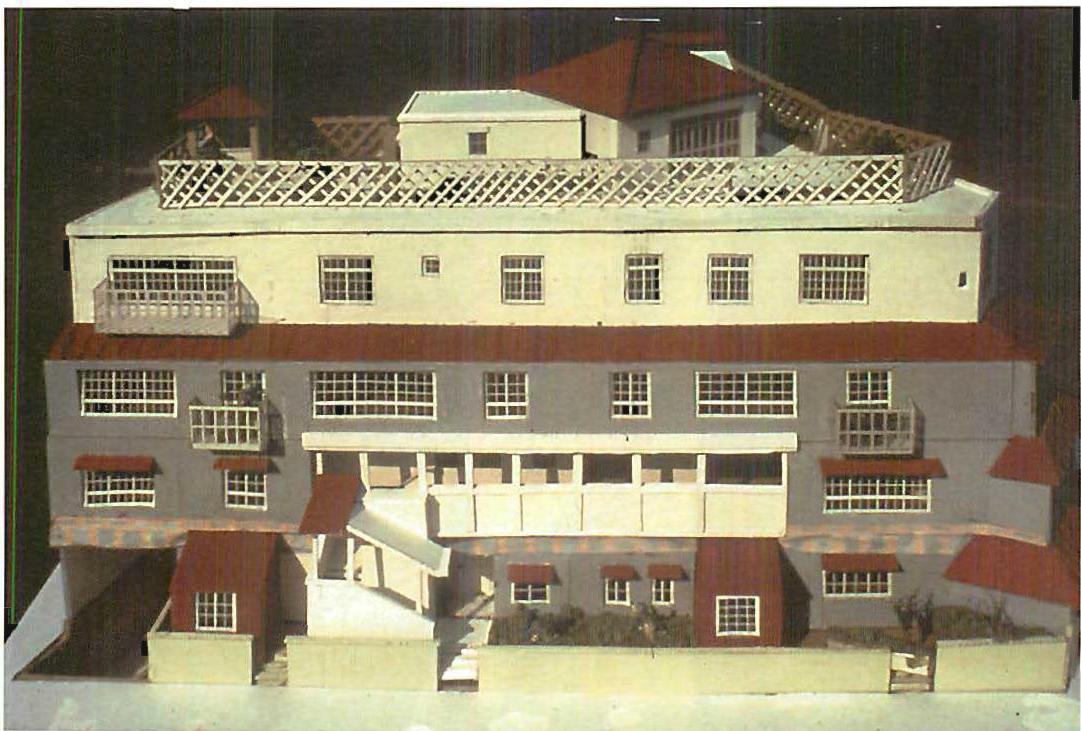

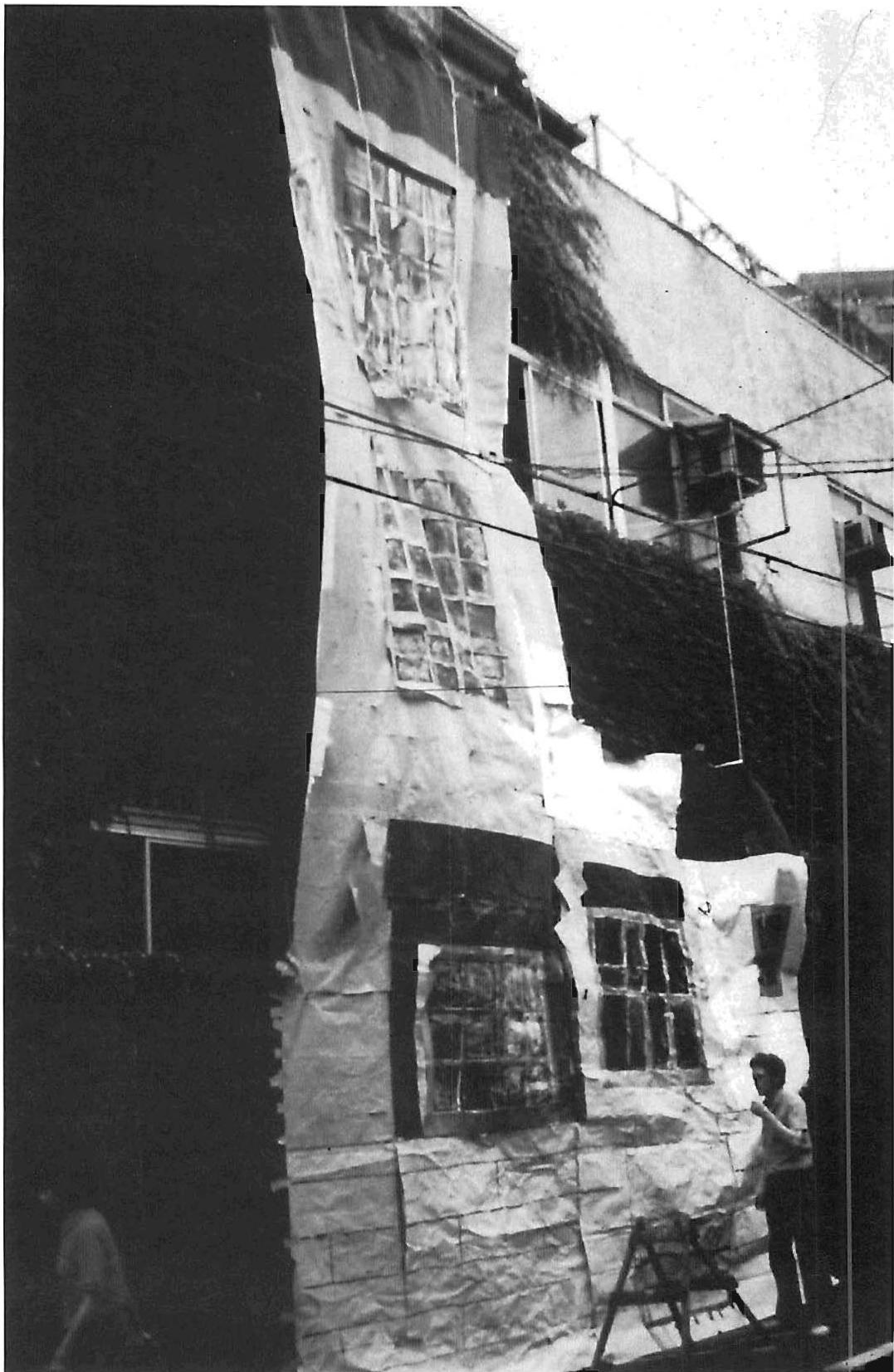

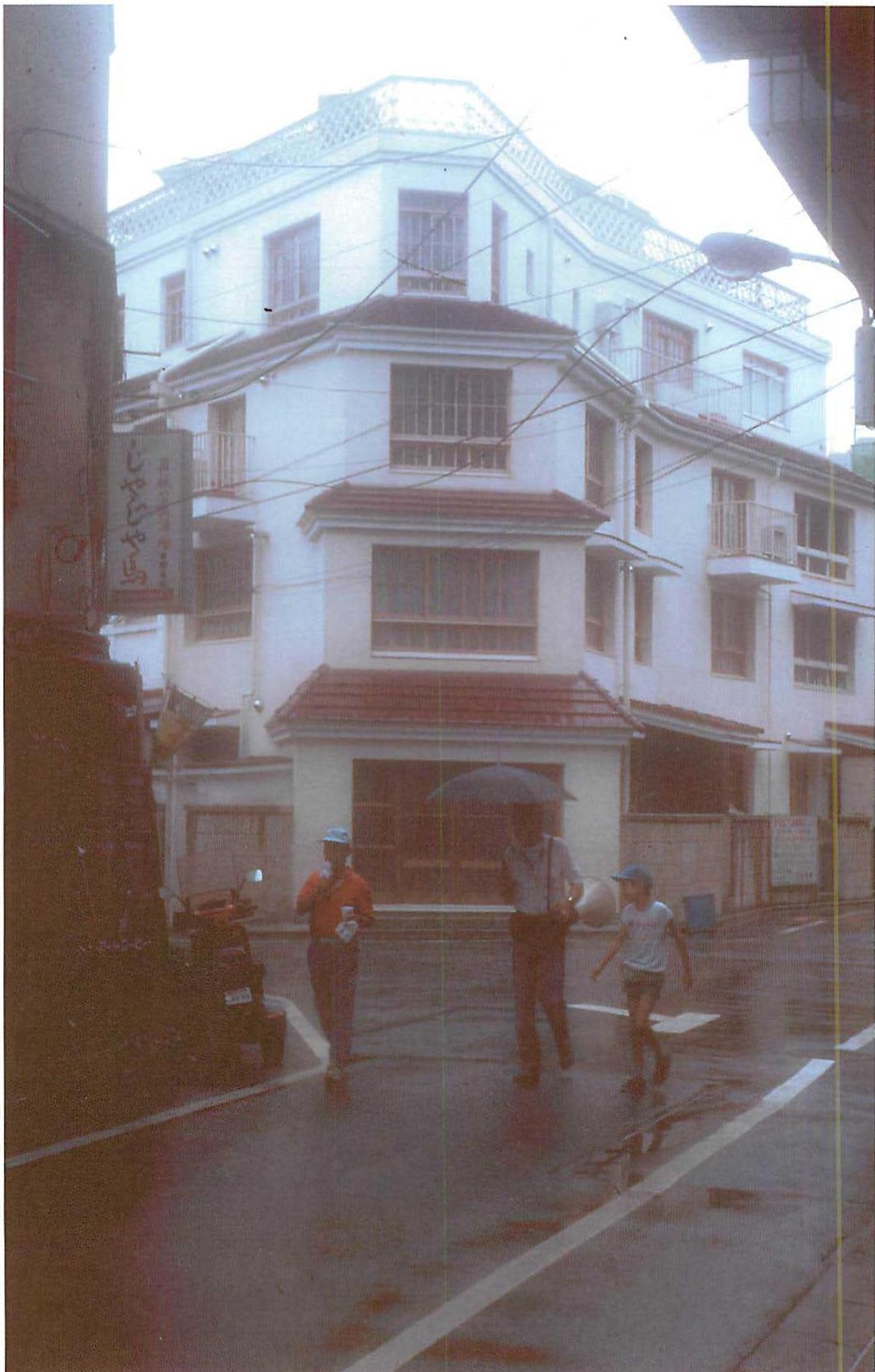

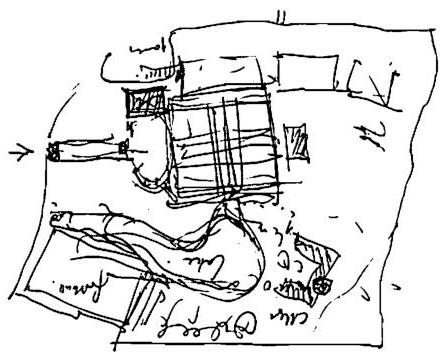

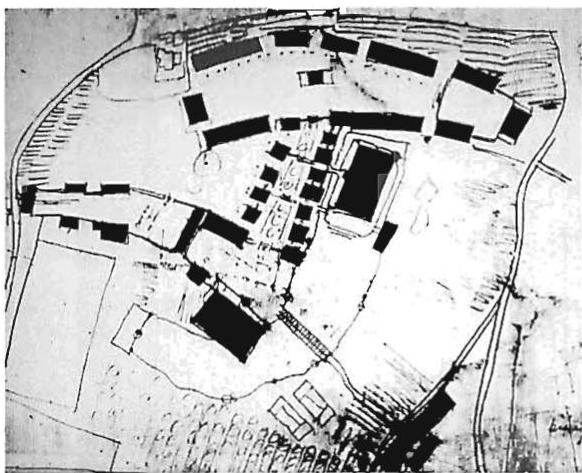

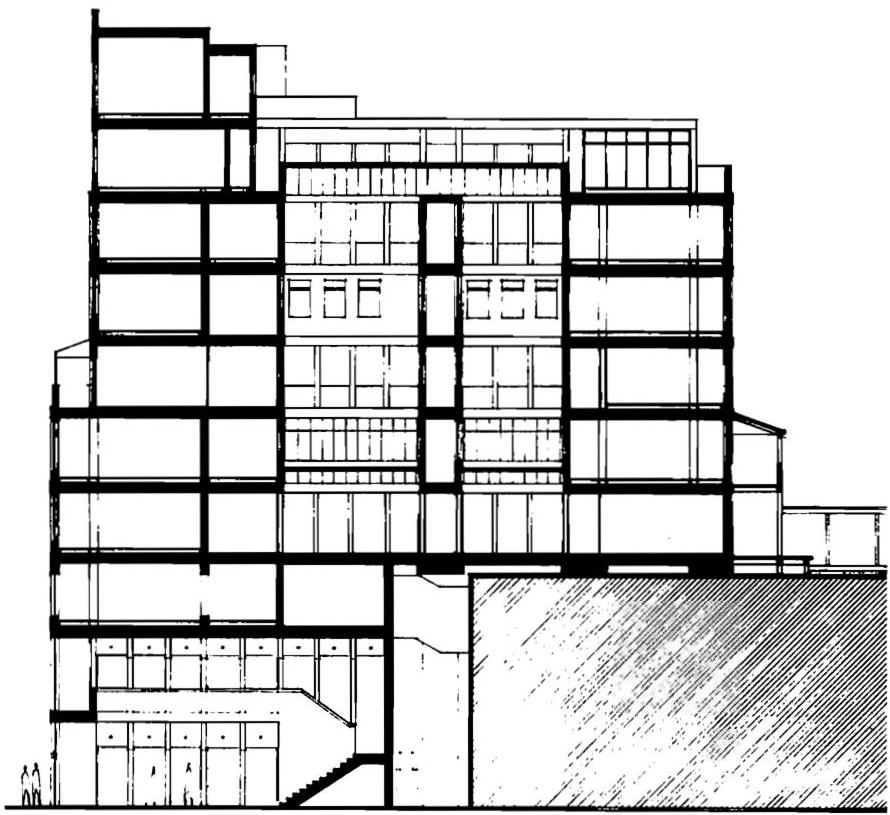

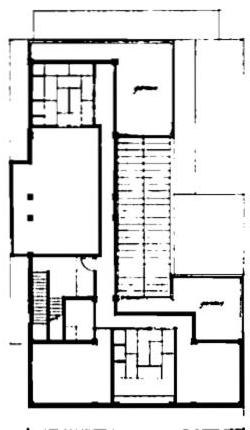

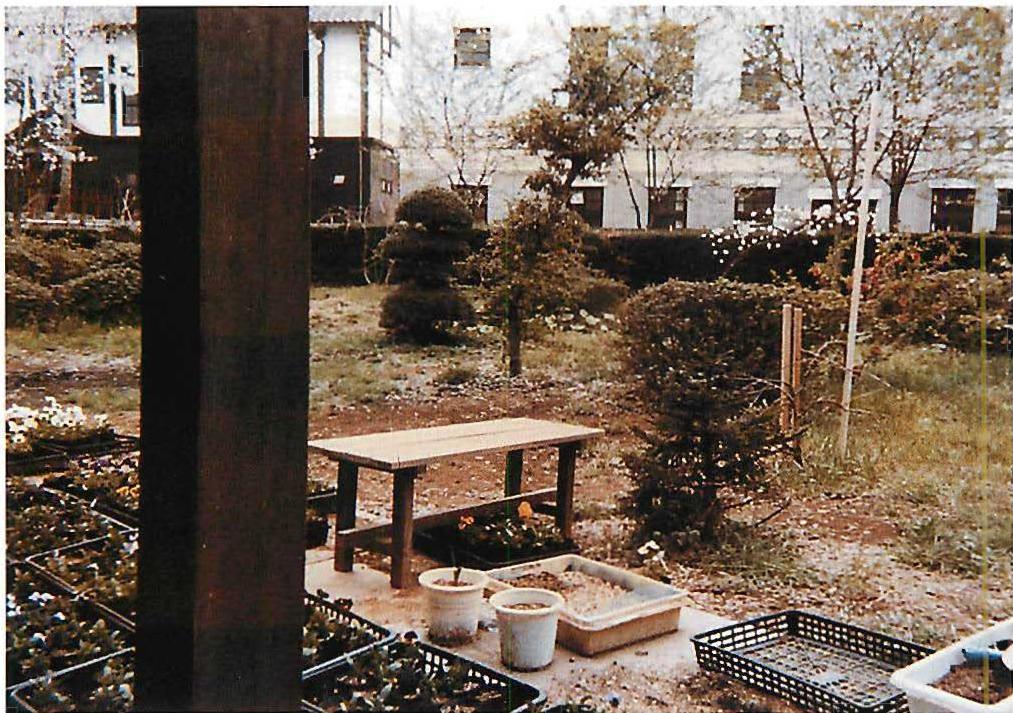

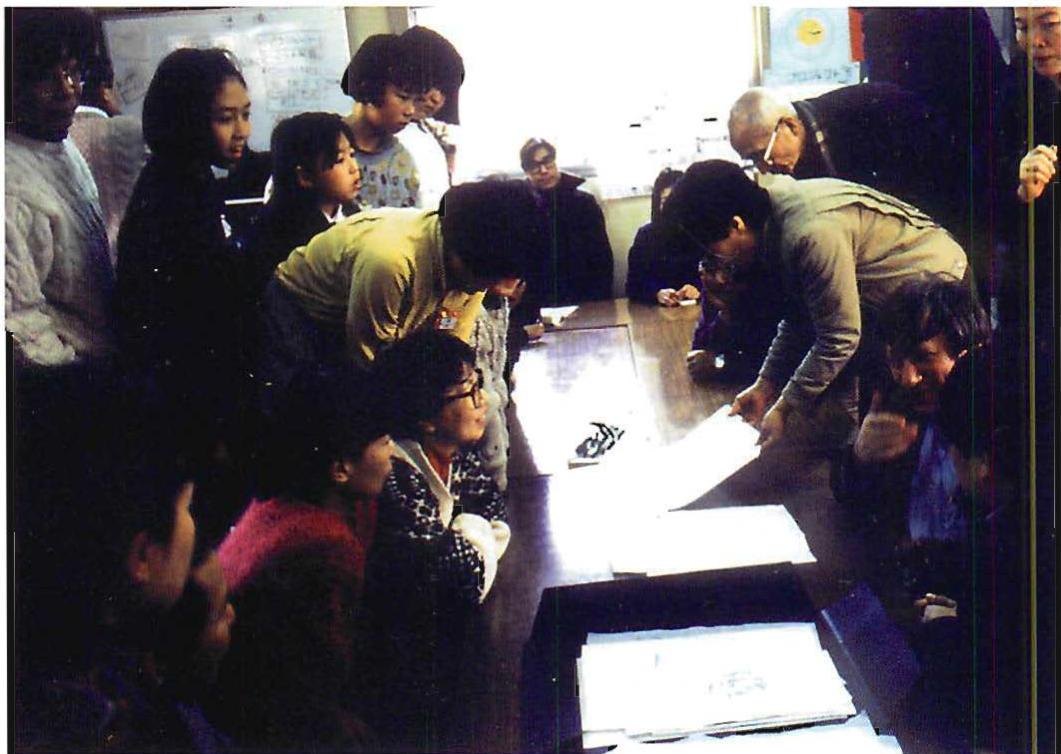

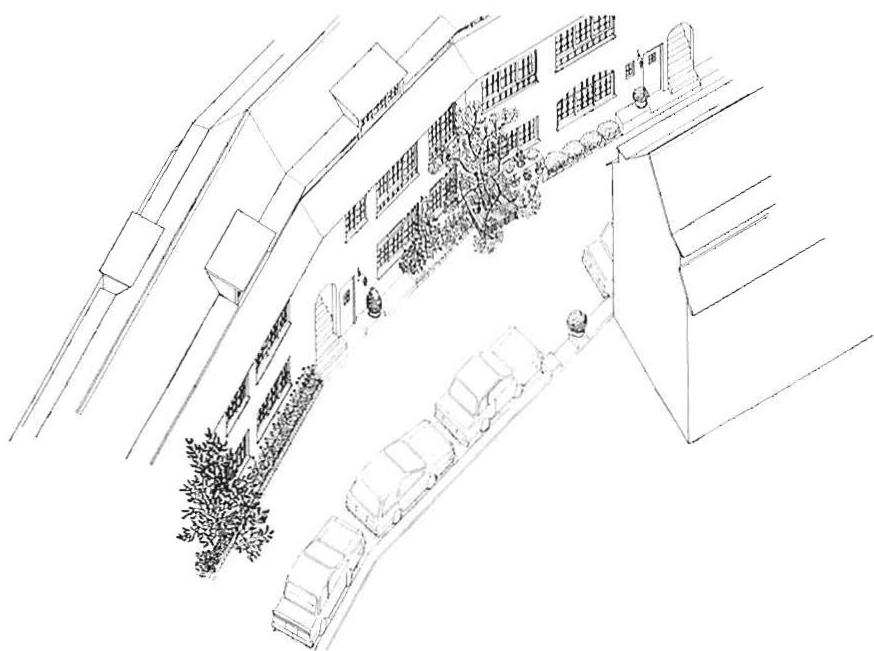

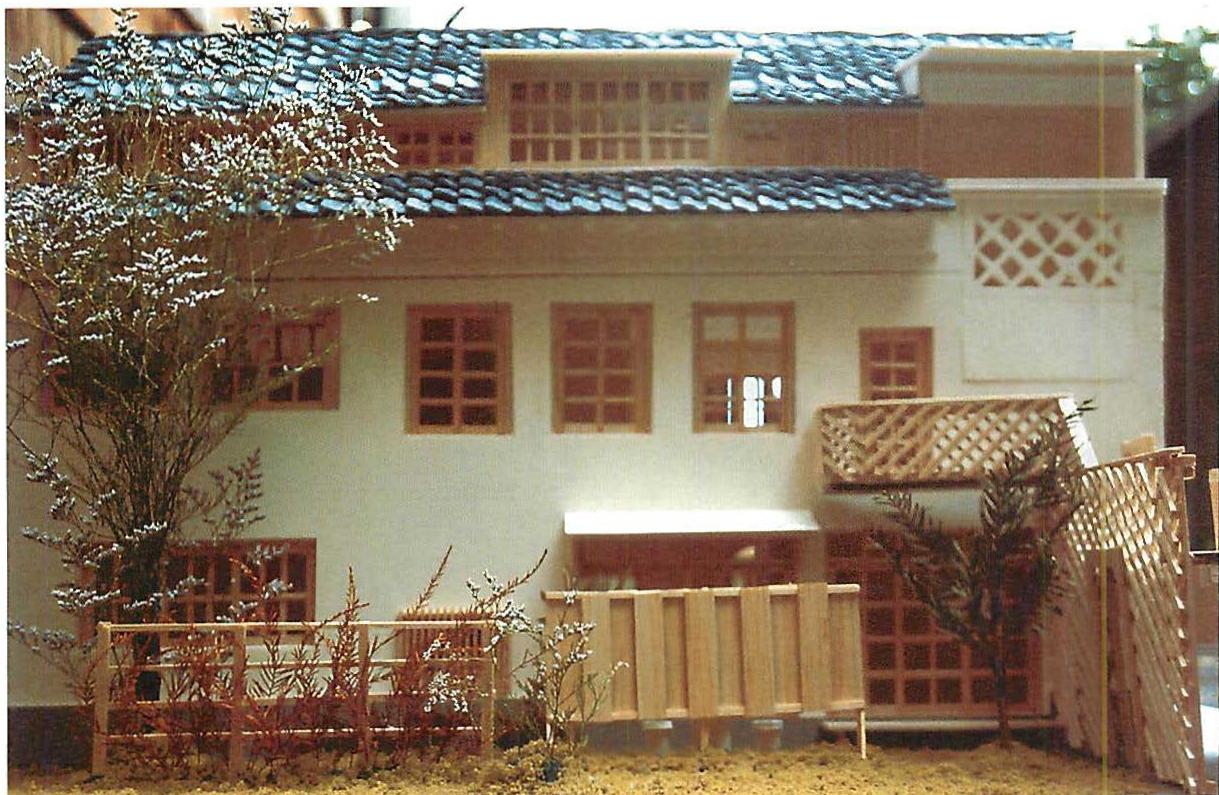

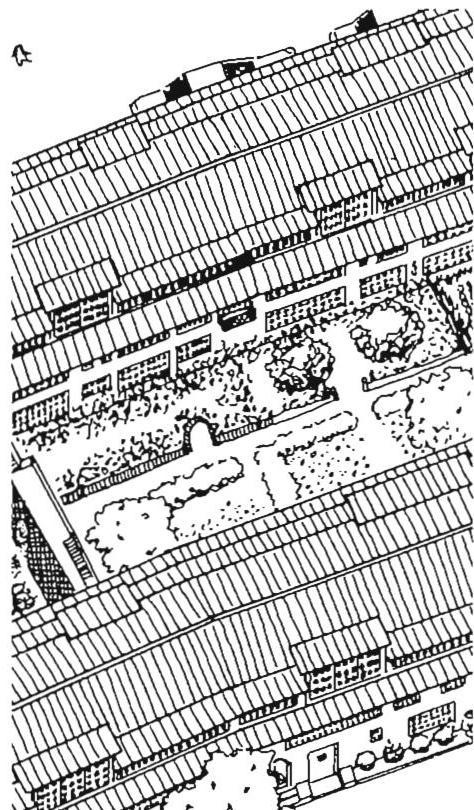

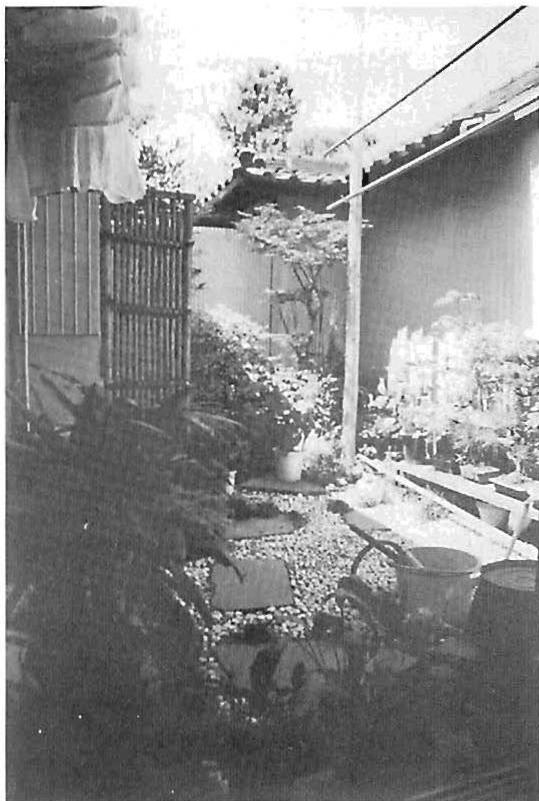

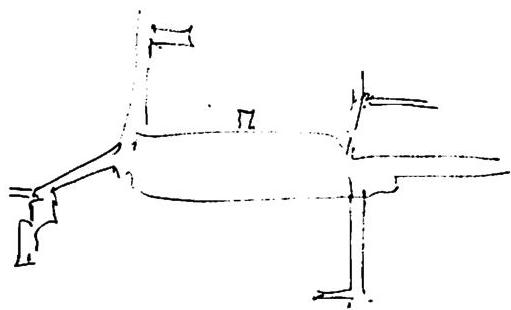

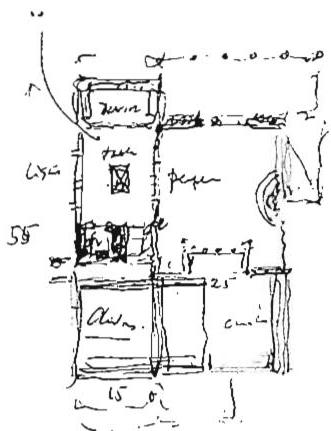

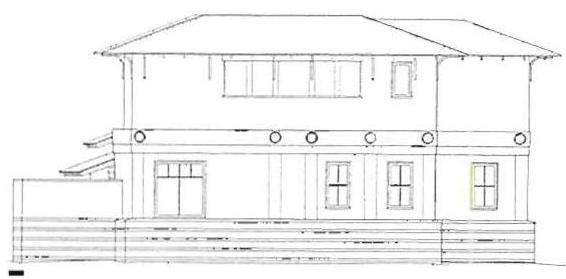

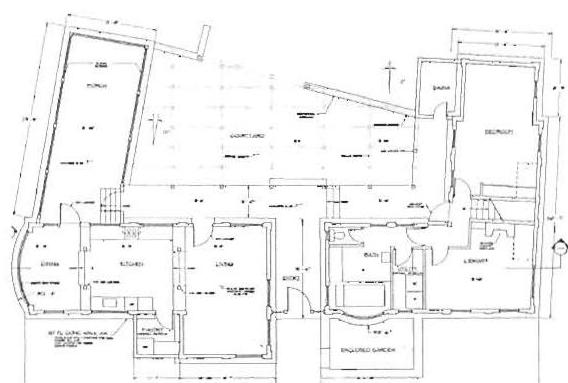

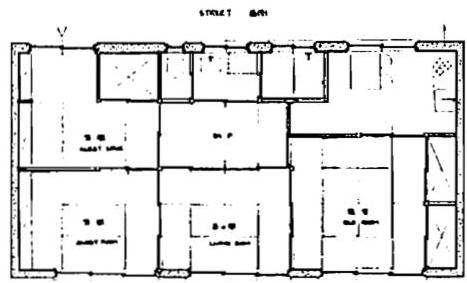

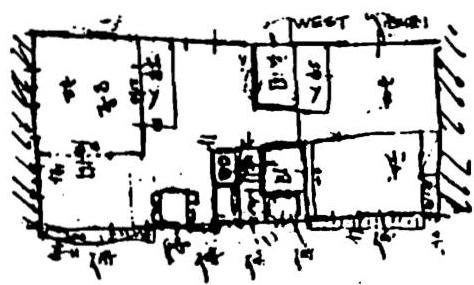

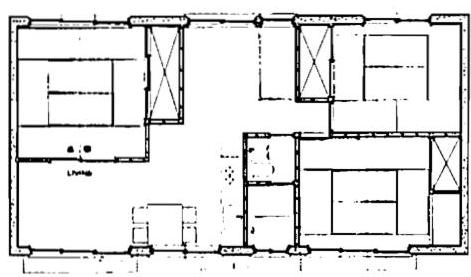

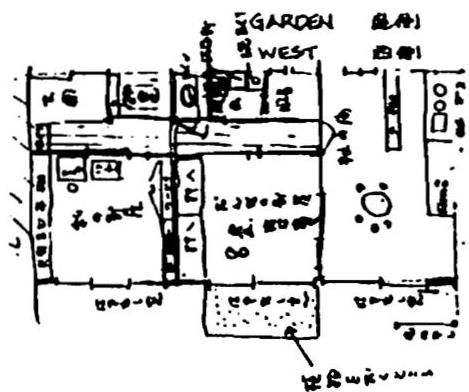

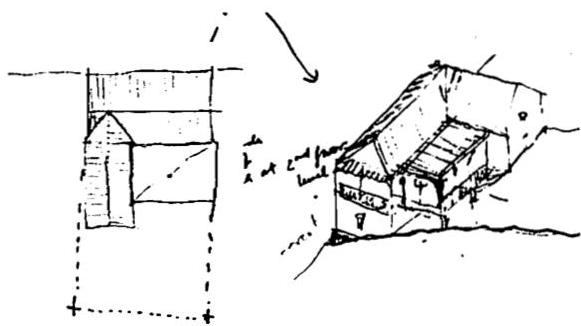

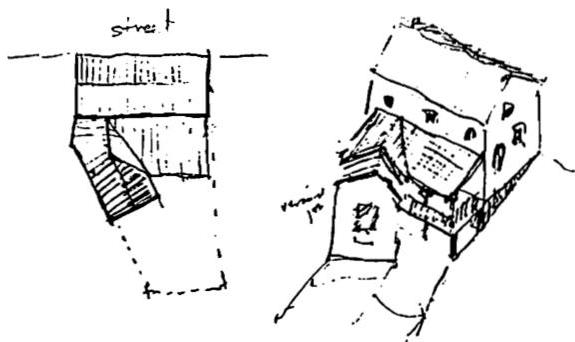

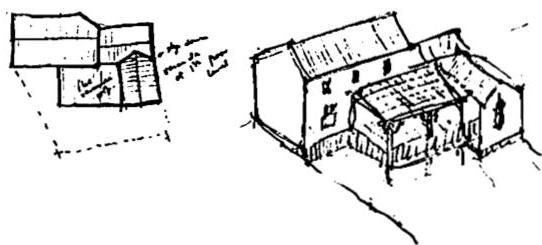

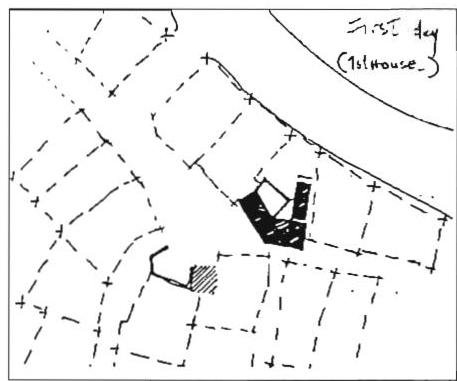

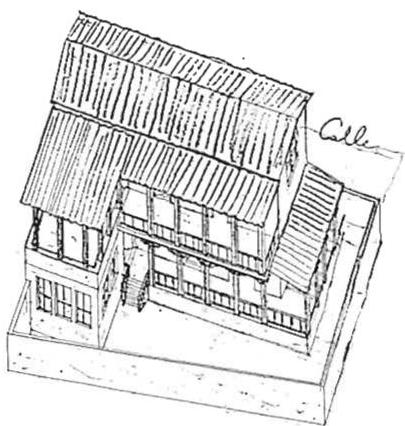

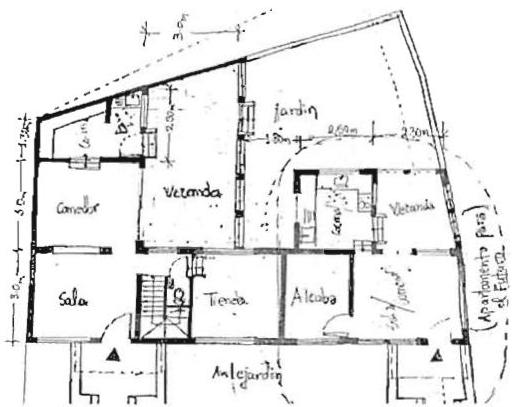

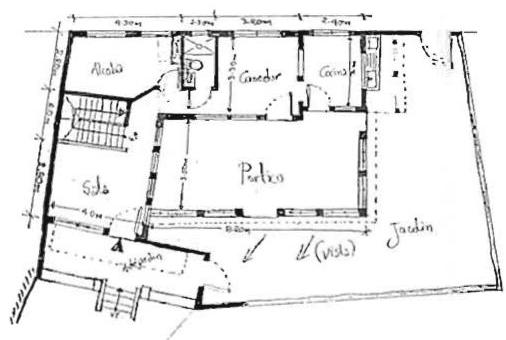

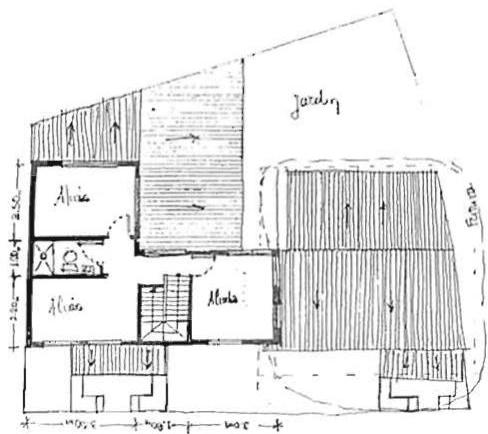

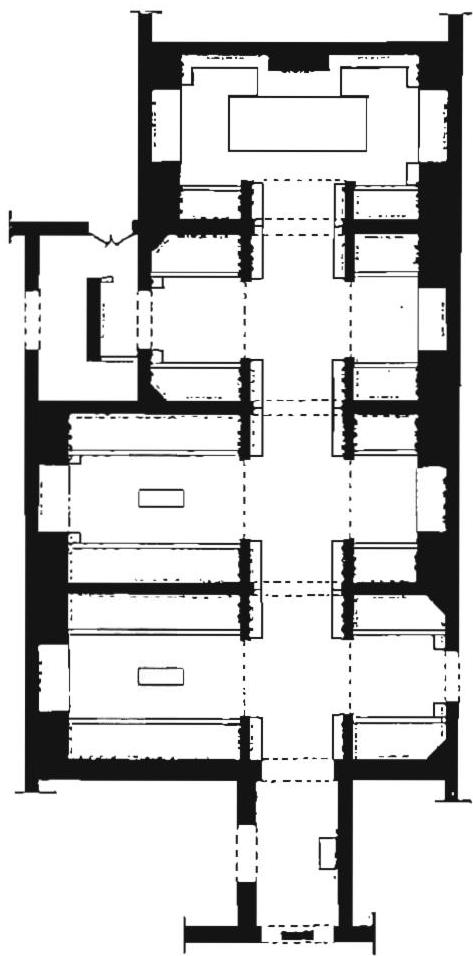

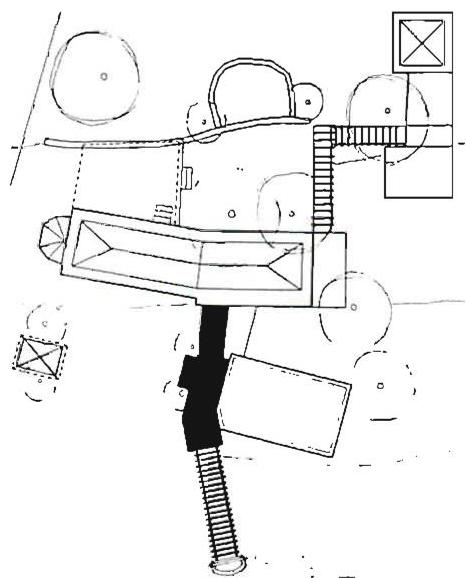

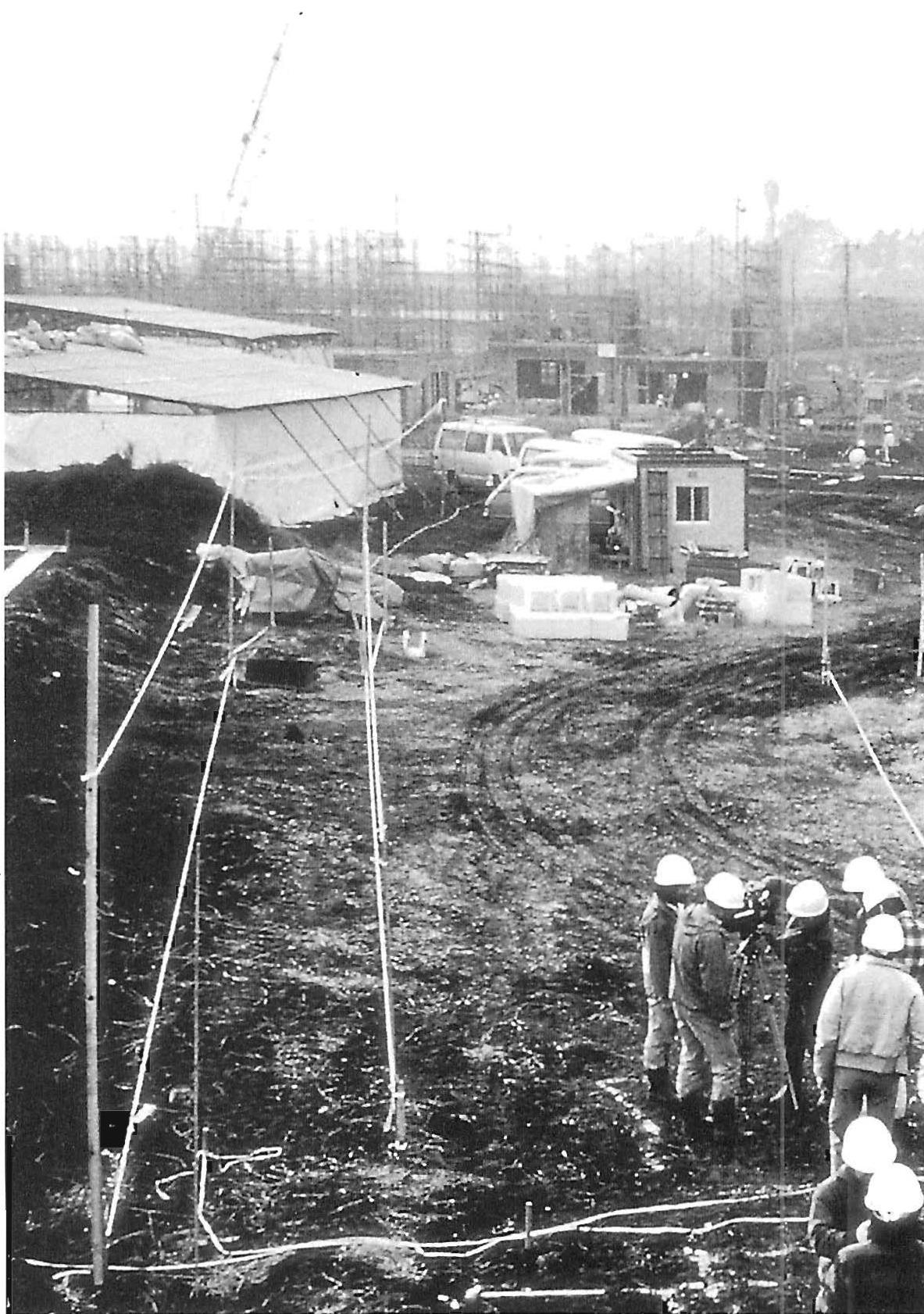

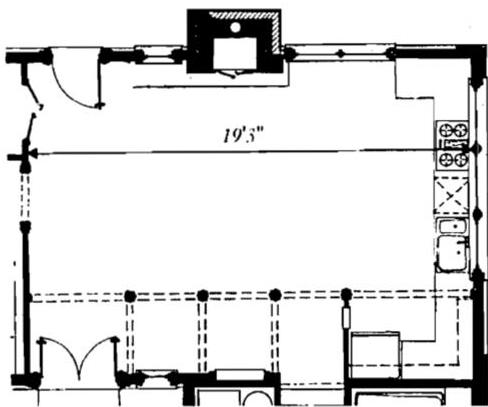

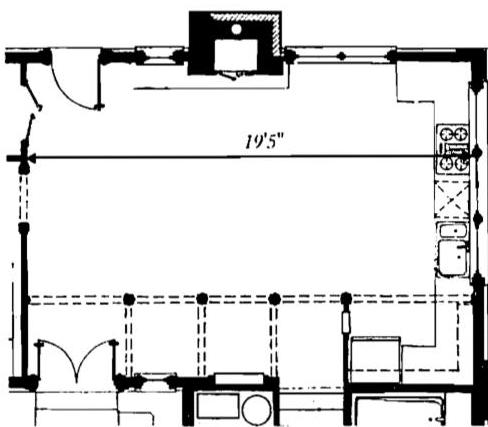

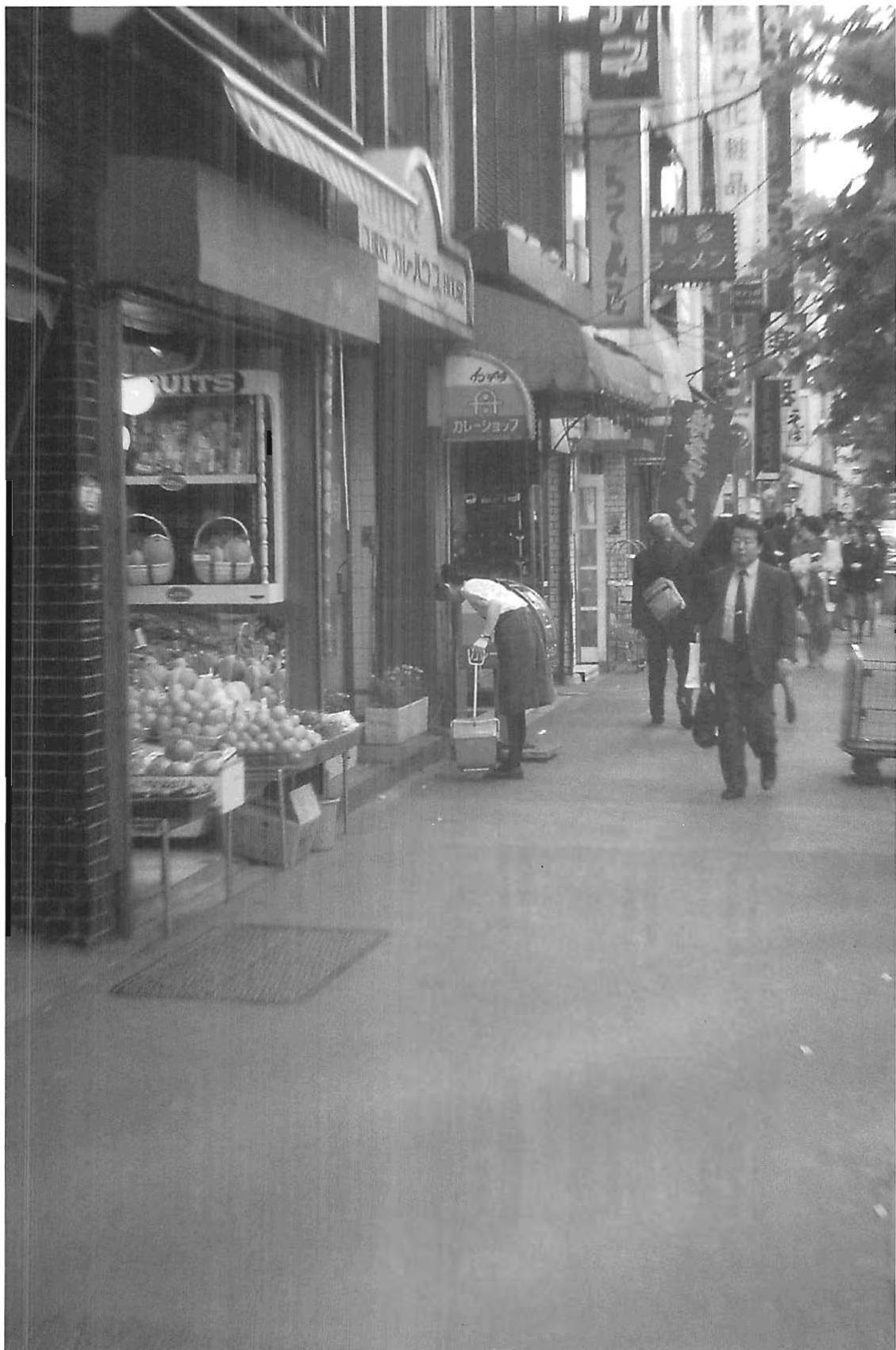

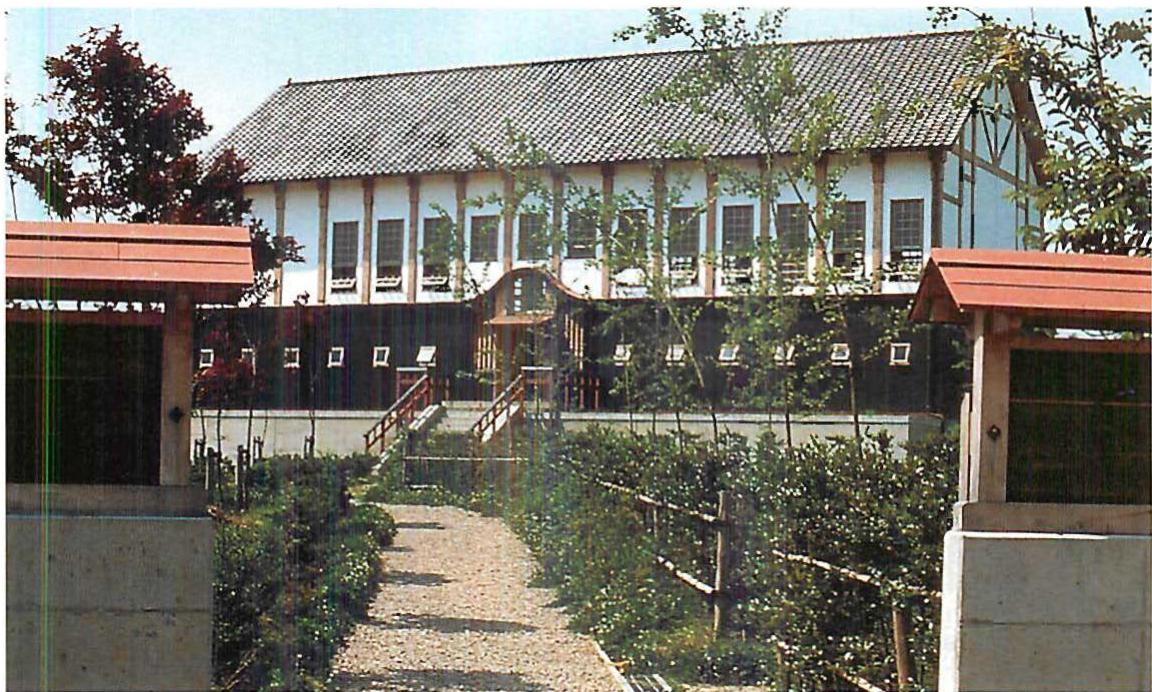

CONSTRUCTION OF AN APARTMENT BUILDING IN DOWNTOWN TOKYO

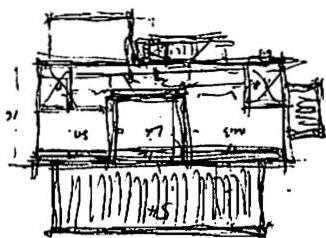

The description of this process—comprising some fifty steps, for initial planning, conception, building design, and building construction—is given at length on pages 166-73. What is especially interesting, is the fact that the steps, even for such a relatively complex building, are very simple yet lead to such a complex design almost without effort.

The first step establishes the building walls as along the street—even though they are at an awkward angle.

The next step decides the orientation of the inner courtyard, towards the sun.

The third step makes terraces step back inside

The fourth fixes the entrance. . .

And so on, for fifty steps, until a simple, but complex arrangement arises from nothing except common sense, and a little bit of structural engineering knowledge.

See the photo on the next page, and the explanation of the unfolding sequence in chapter 5.

A VARIETY OF OTHER PROCESSES, ALL SIMILAR IN FUNDAMENTAL CHARACTER

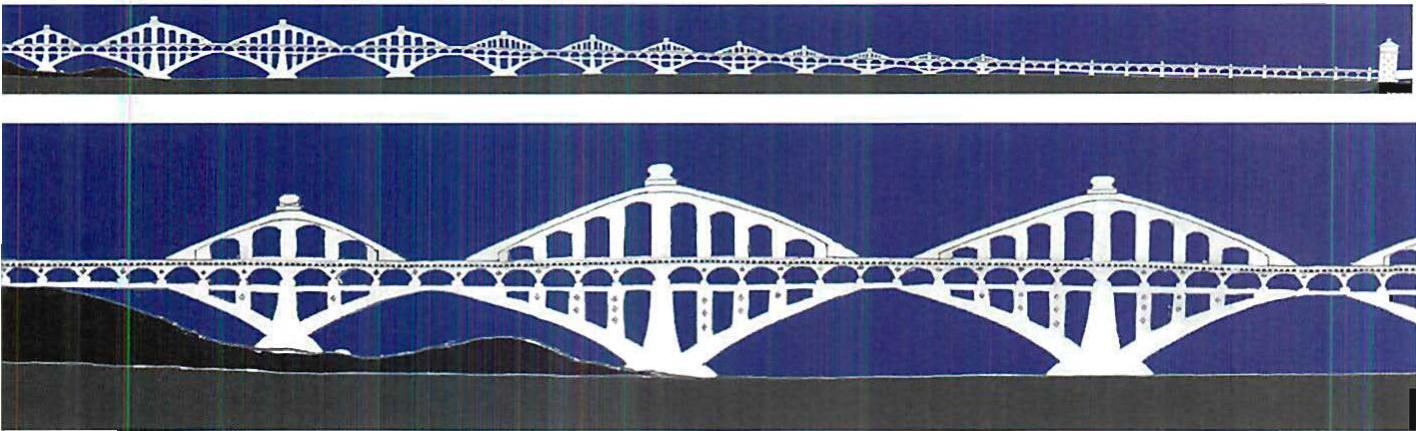

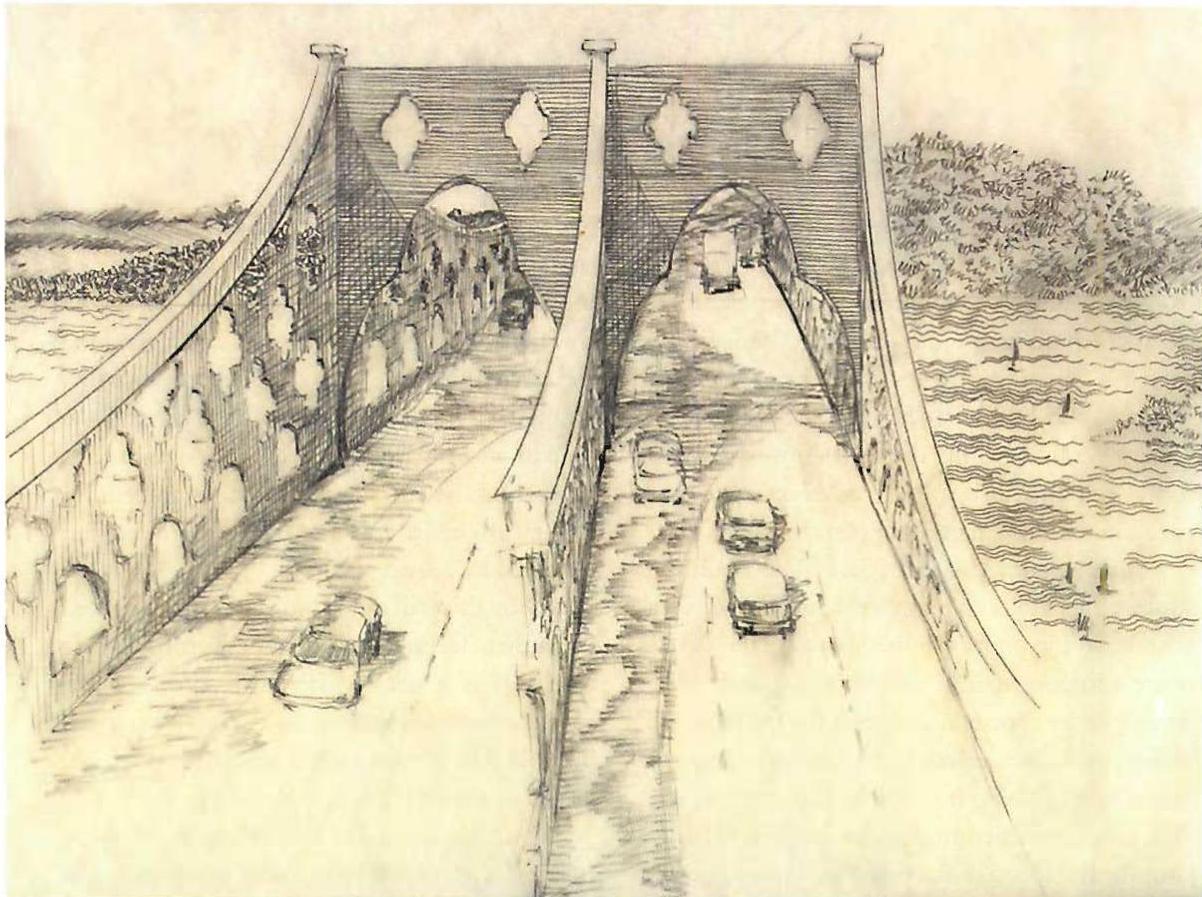

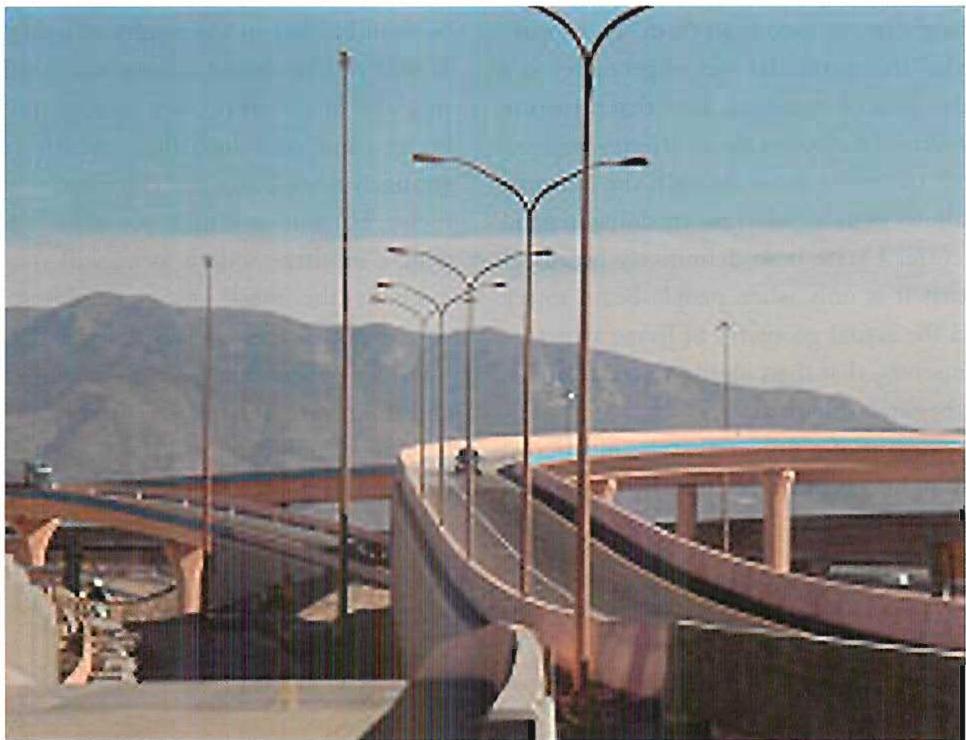

In yet another instance, I may look at a proposed new bridge we are designing and ask what shape of bridge, what shape of span, what shape of tower, is harmonious with the land-forms and water that it passes over. Analytically, I may well be looking for the center (in the space between the bridge towers) which most enhances the water which the bridge is passing over. Am I thinking about it this way when I do it? Generally not. I try to make the bridge in the best way I can, and I rarely talk to myself explicitly about the centers — unless I feel I am going off the track and need to bring myself back on track.

Another time I may be talking to clients about a room that is to be built, listening to hear what they are really trying to say. That is yet another way I might try to get insight about the living center which they are searching for.

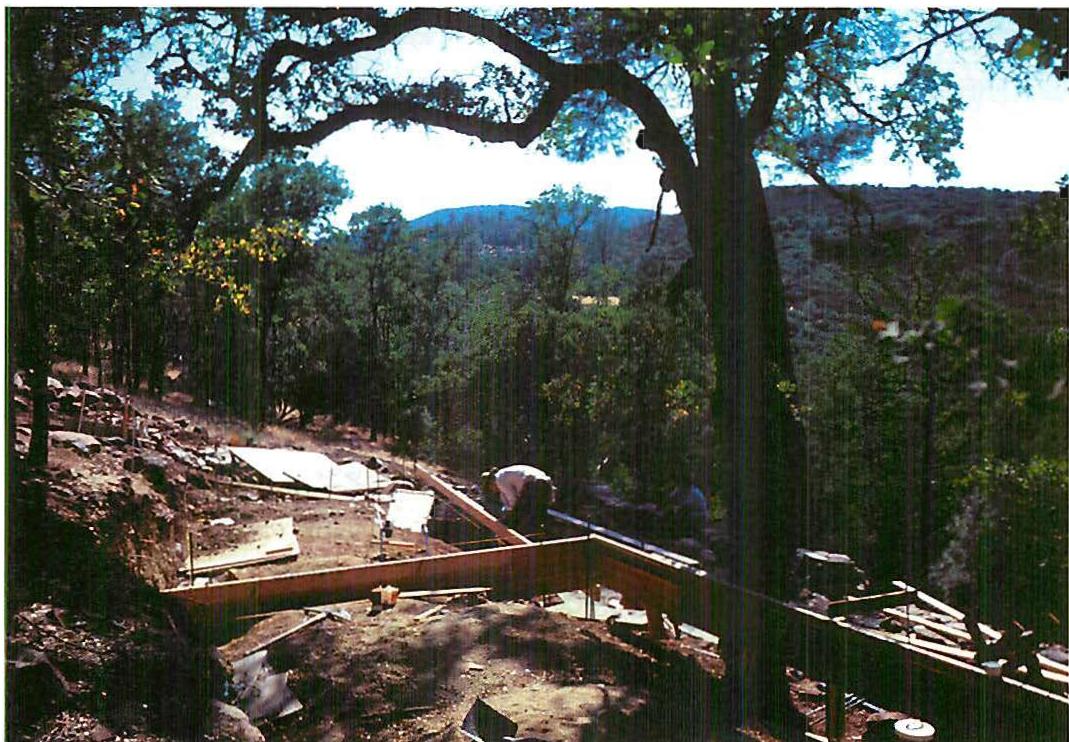

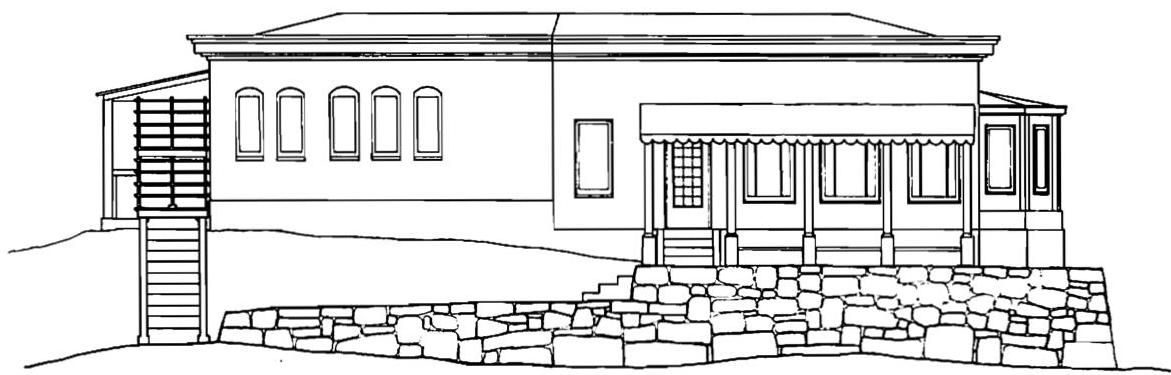

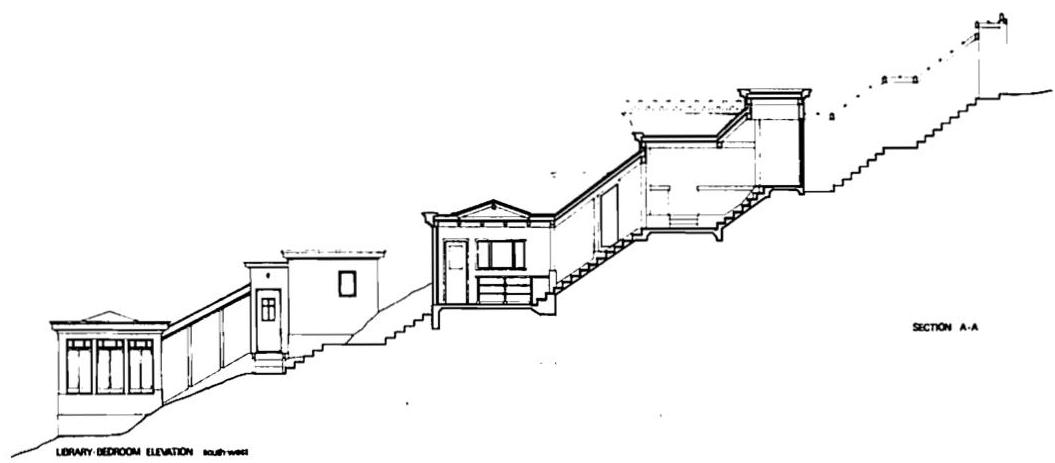

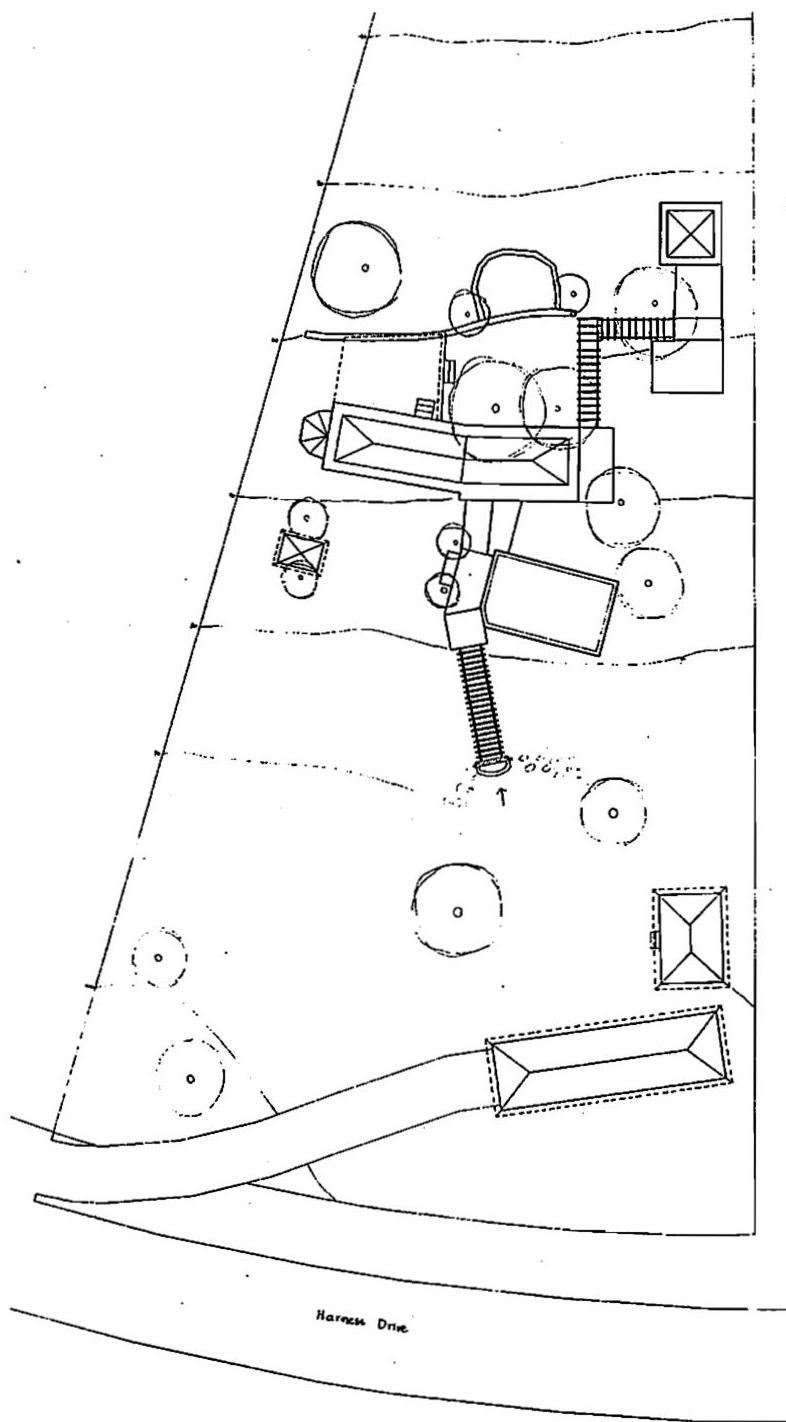

In another case, looking at a new building site for the first time, I drive along, gazing at the trees and the spaces they form, and wondering

what it is about these trees. I could be looking at the trees, thinking about the way they form a structure that is objectively present in the wholeness they help to form, trying to grasp their essence so that I can take new actions which preserve their structure.

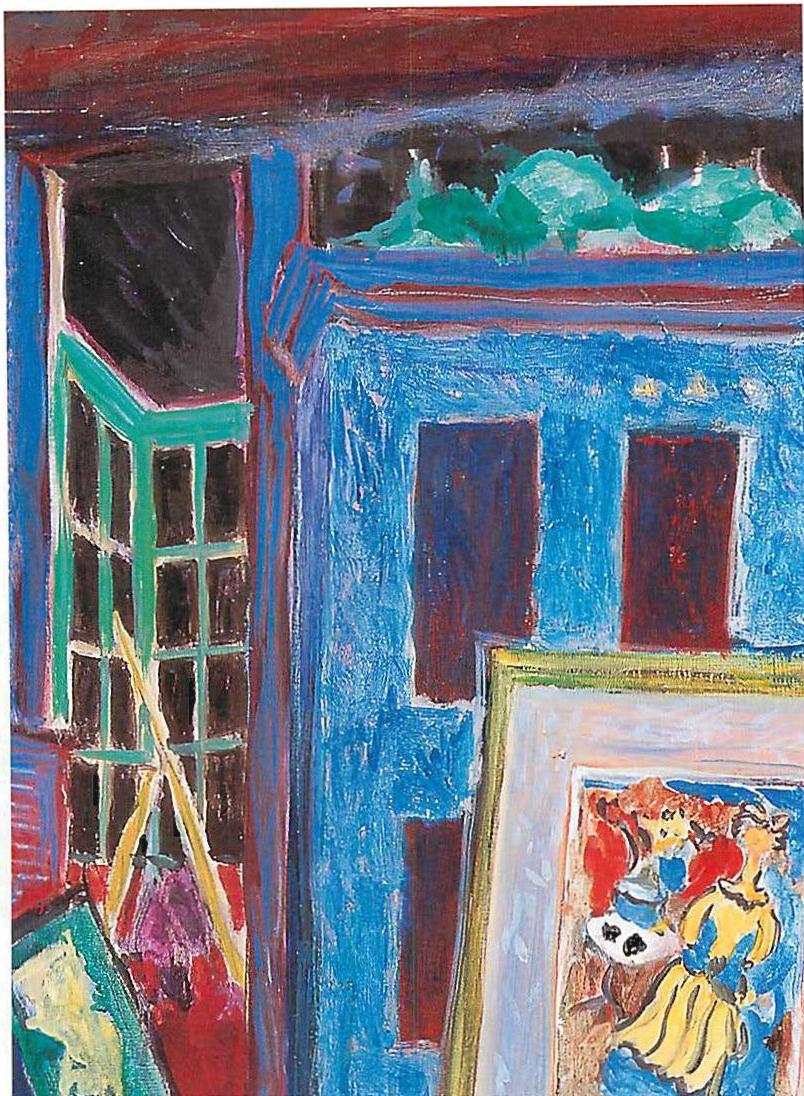

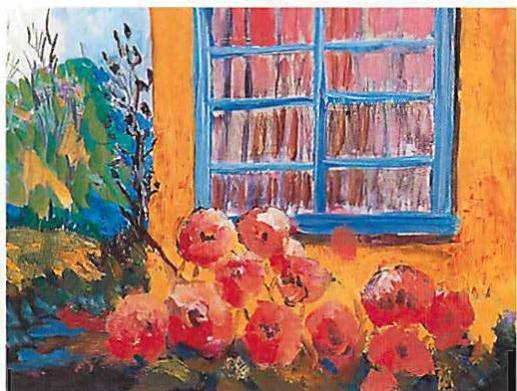

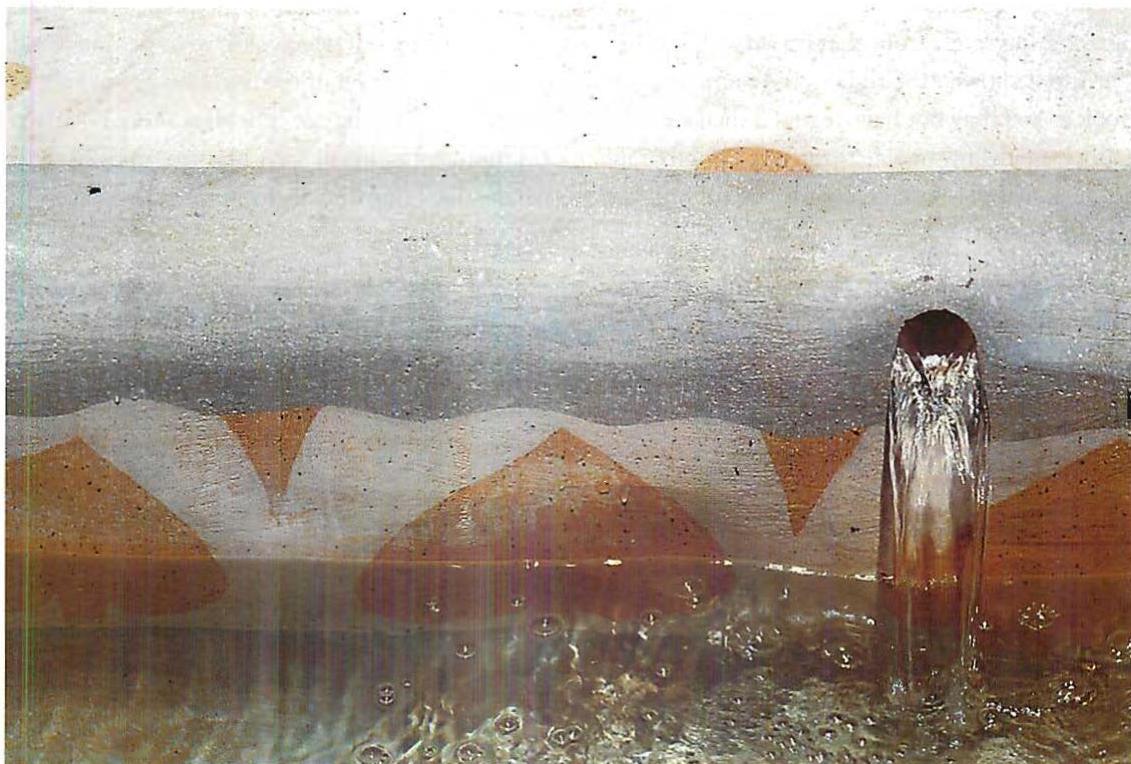

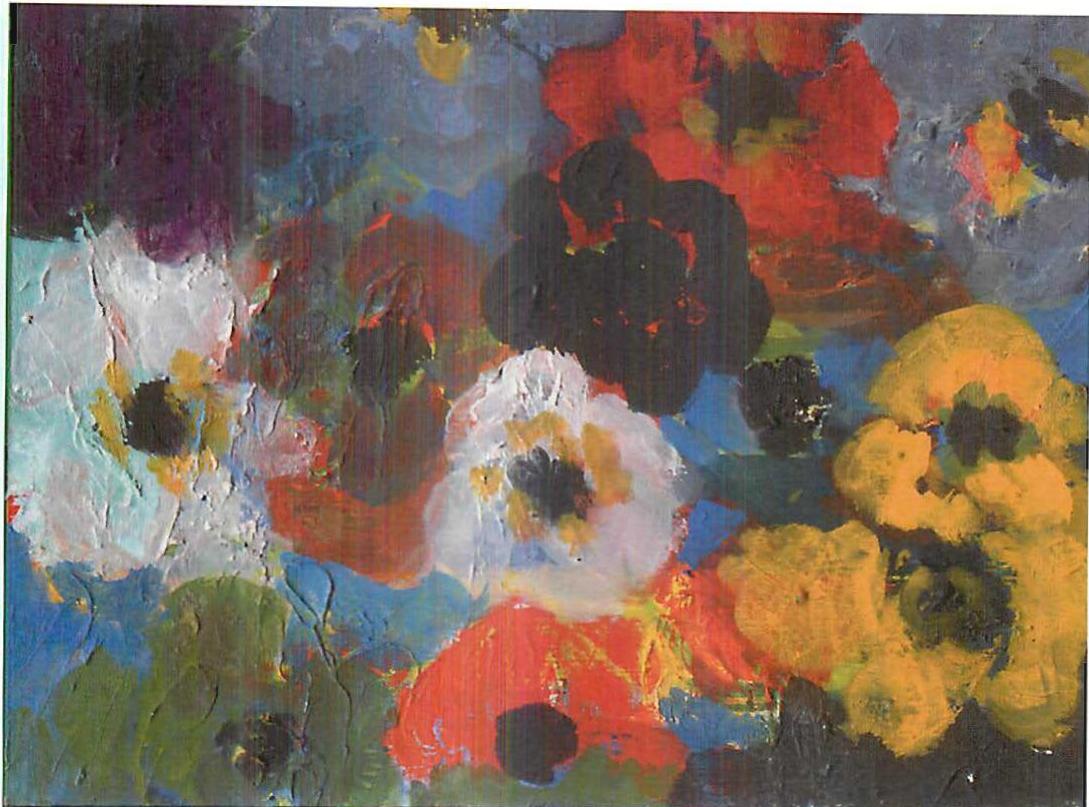

Or, if I am painting, I may look at the light on a distant mountain and try, within the painting, to put a patch of color in that place so that the color shines, and lights up the landscape in a way that is reminiscent of the real place's character. Again, if I force myself to be analytical, I can say that I am at that moment trying to construct that flash of light as a center which illuminates and strengthens the center which is the mountain, and that this in turn is being done so as to strengthen the center of that landscape as a whole. But what I am really doing is trying to get that patch of light just right so that the colors work together, concentrating on that. That, too, is an instance of a living process.

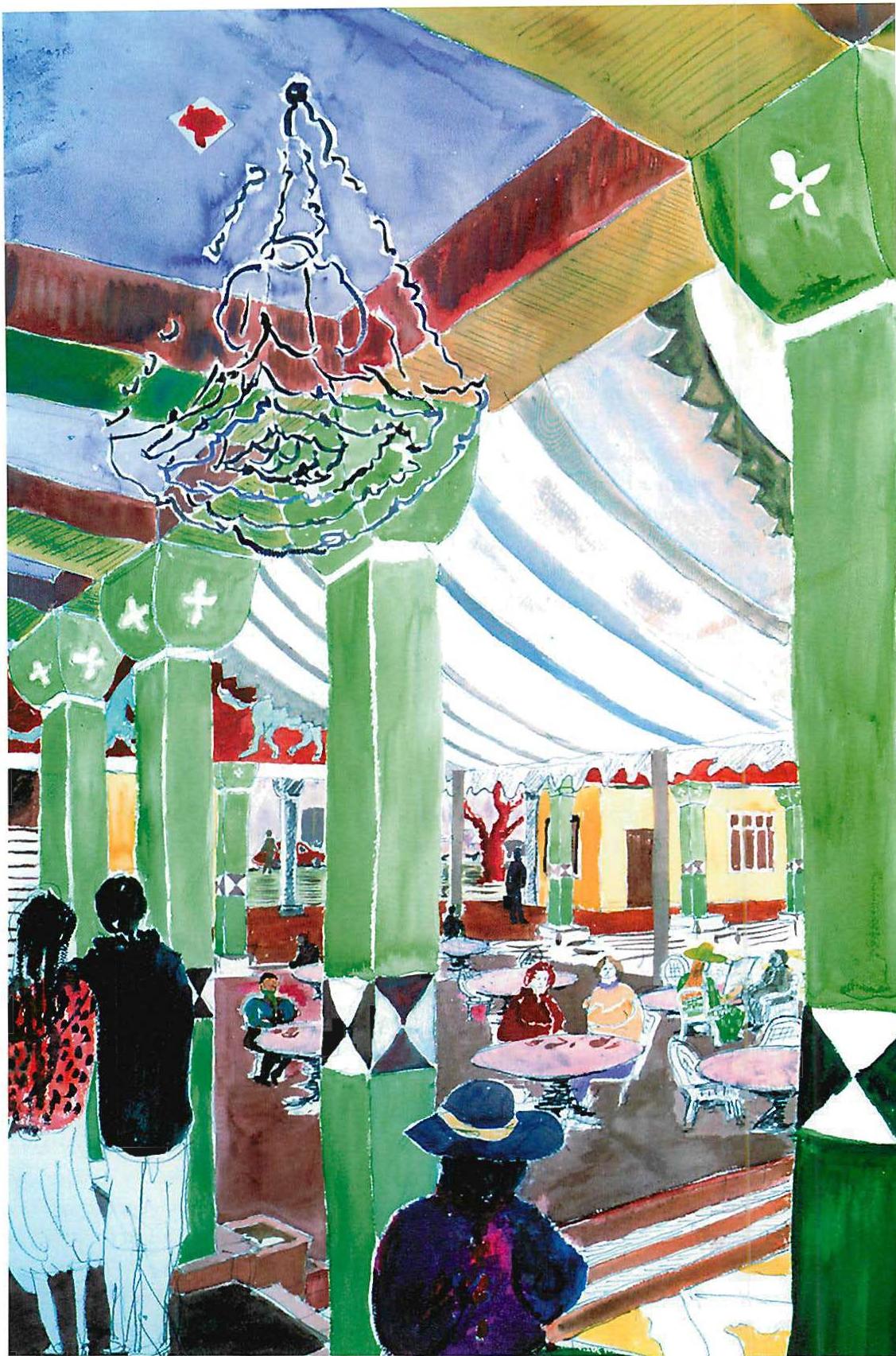

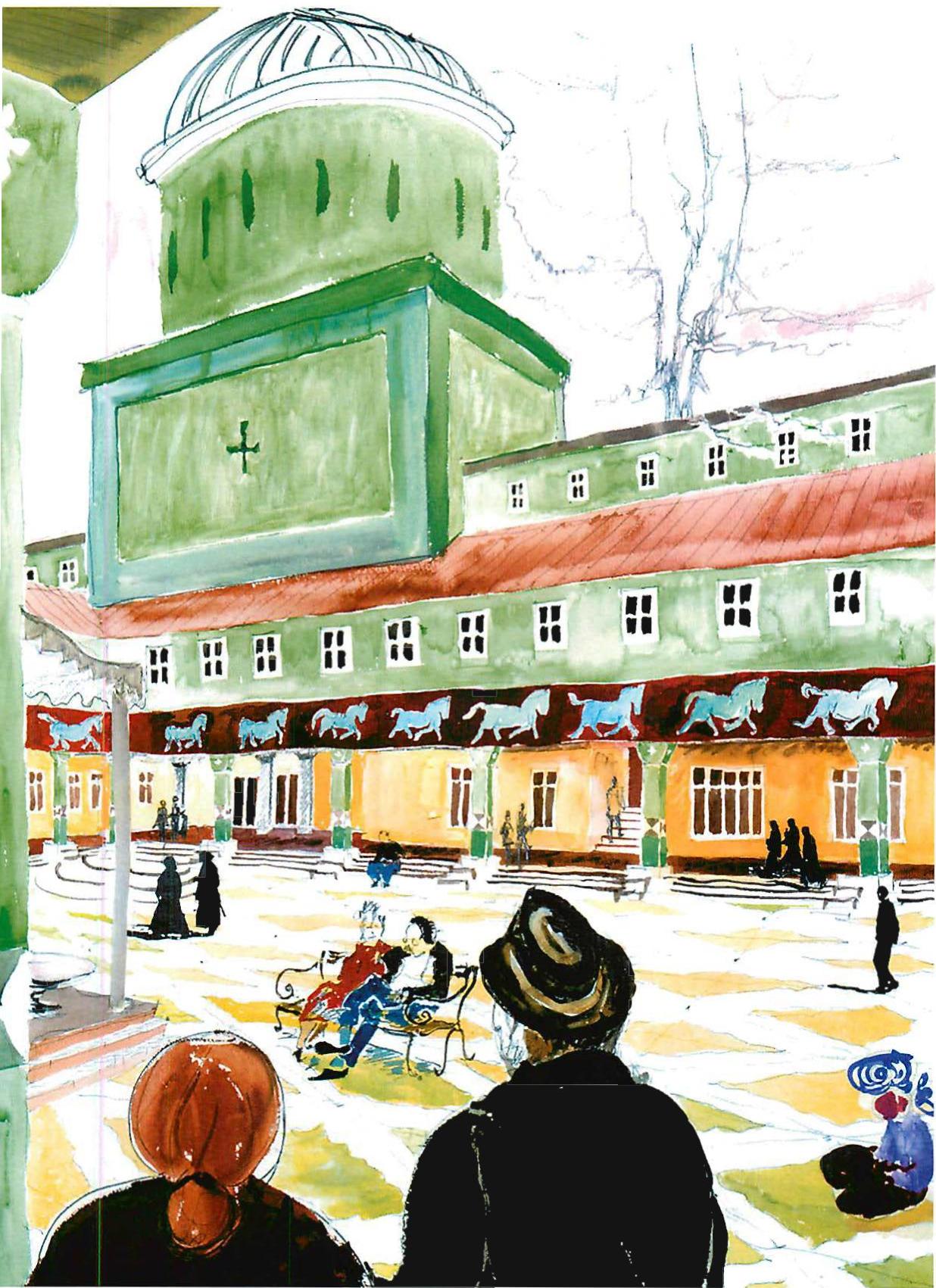

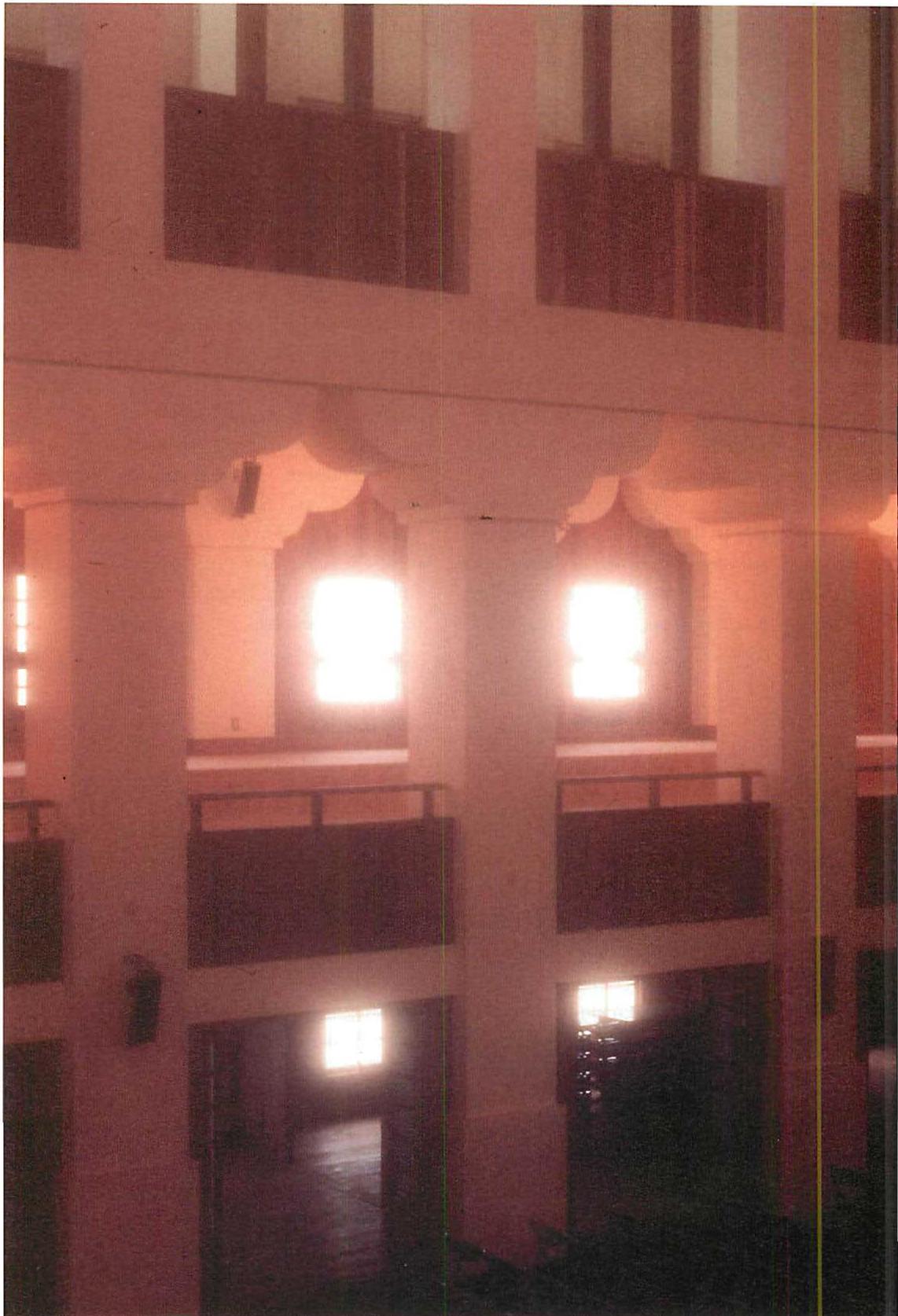

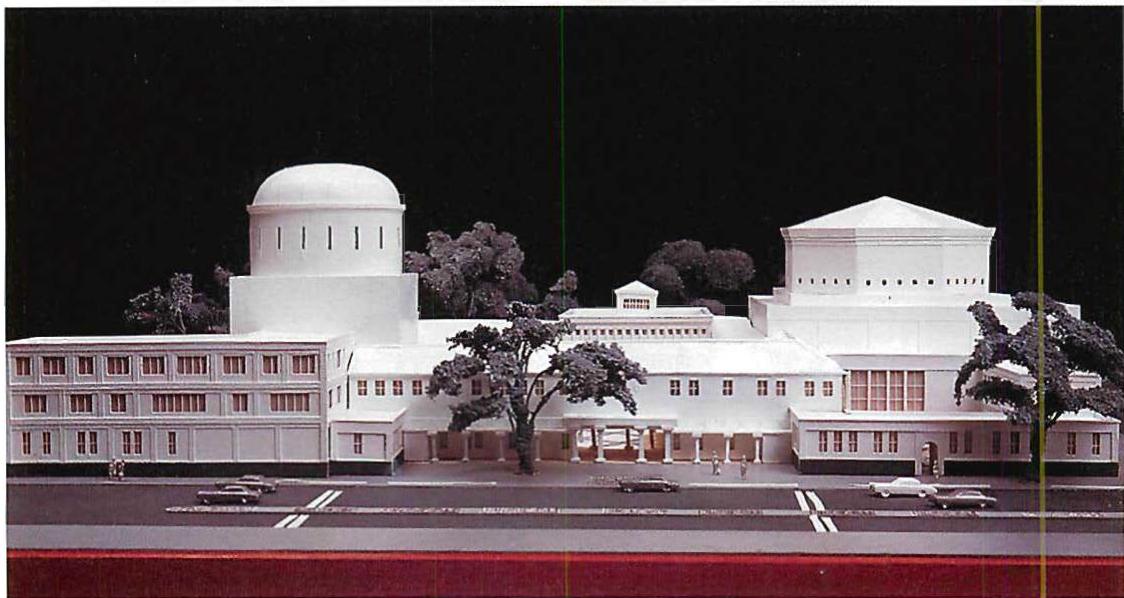

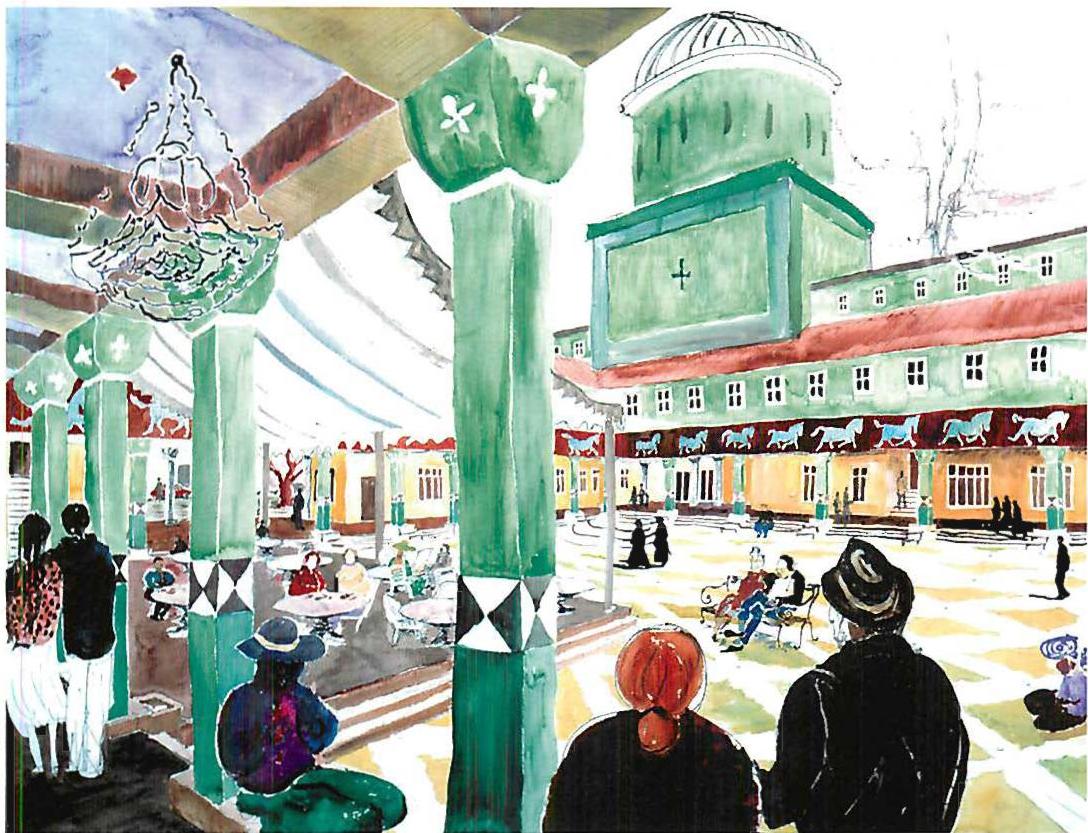

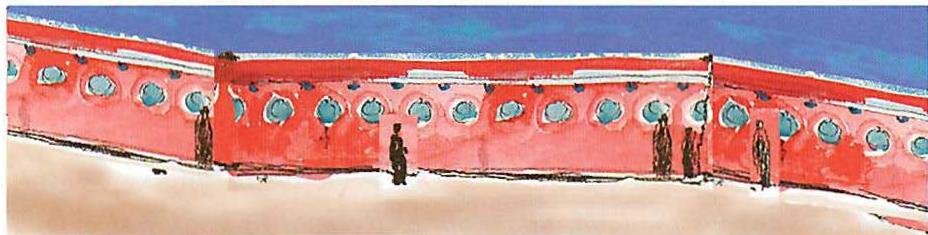

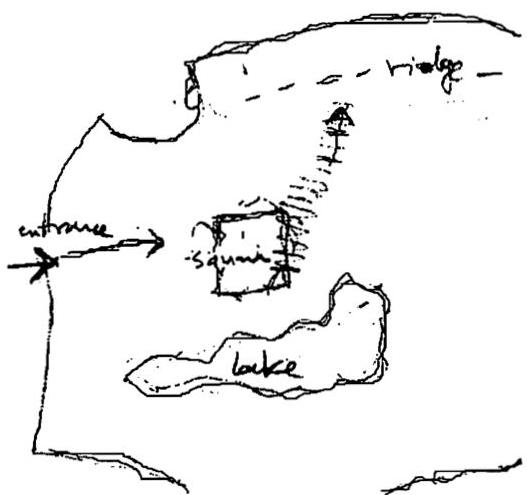

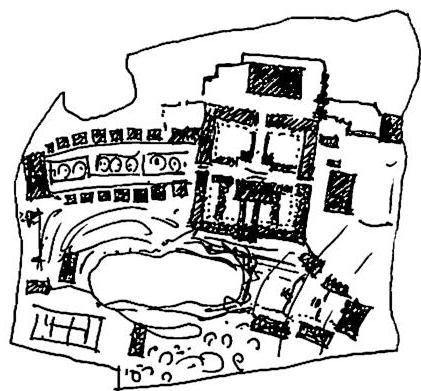

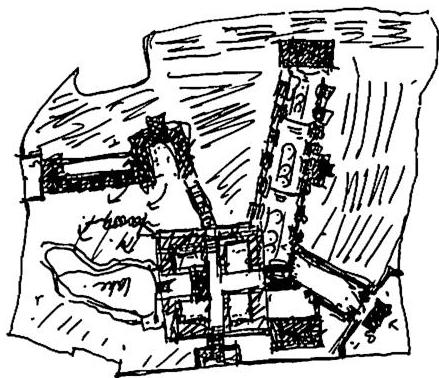

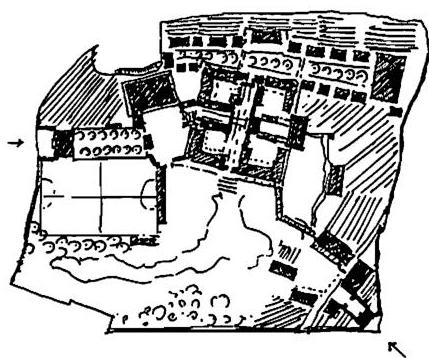

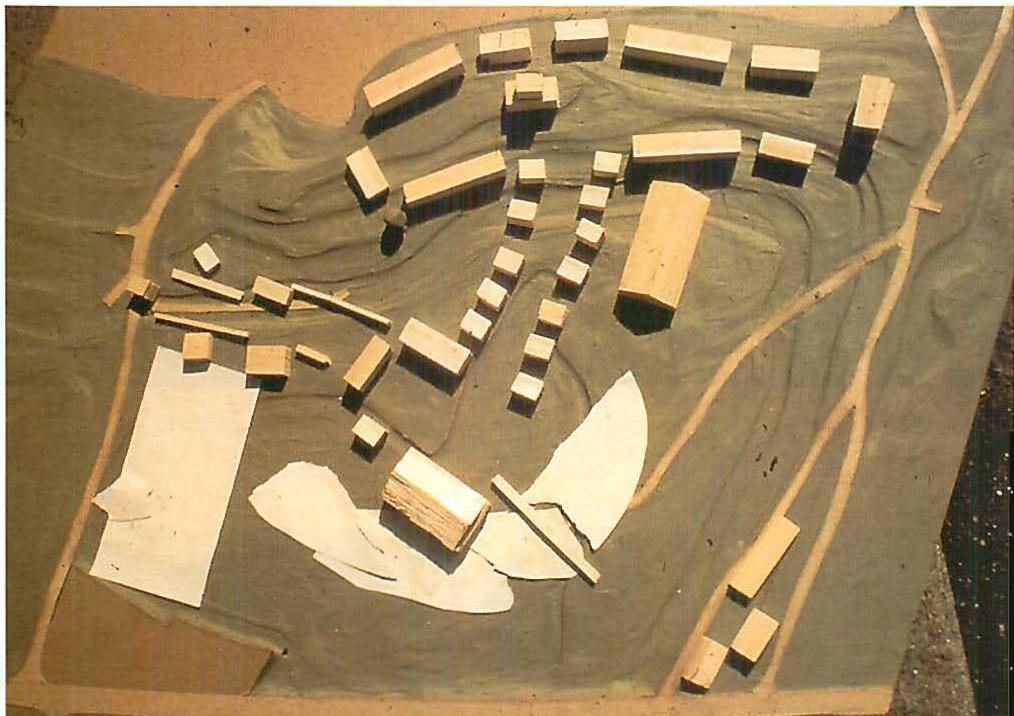

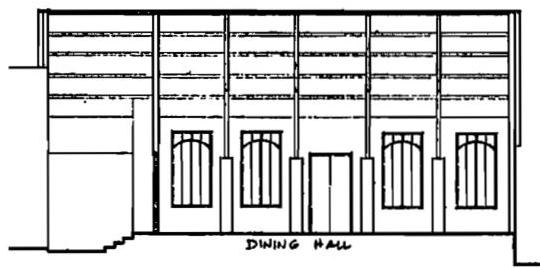

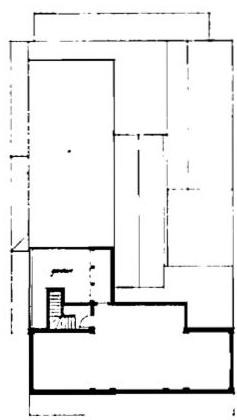

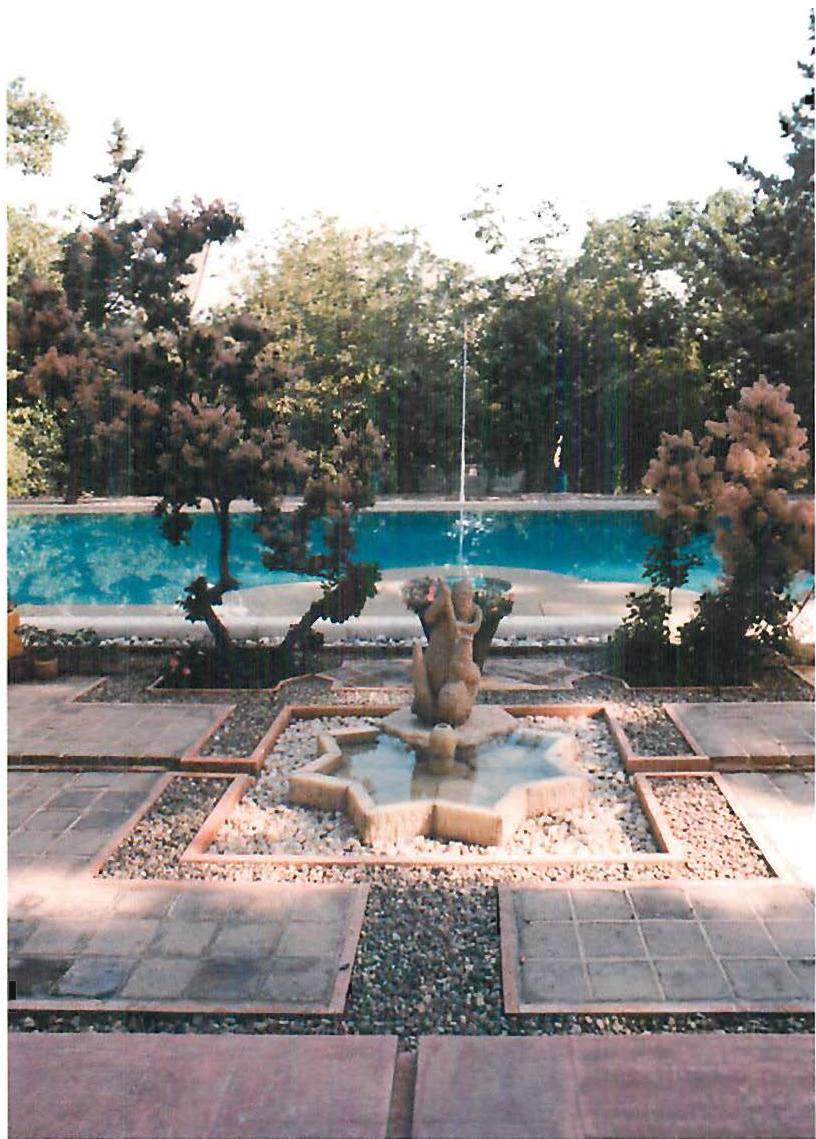

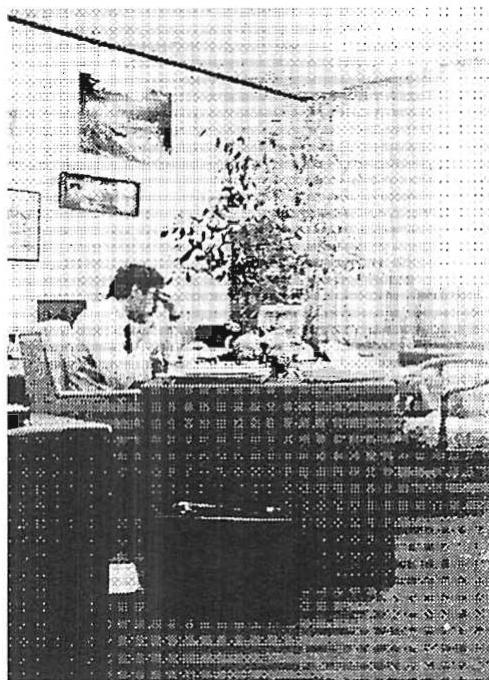

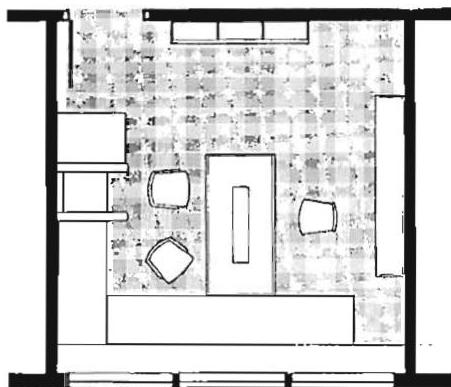

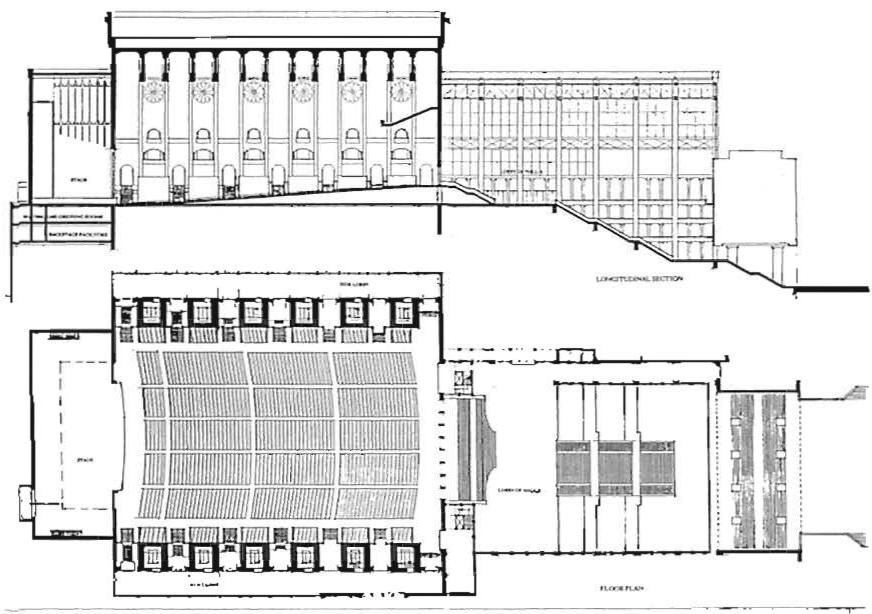

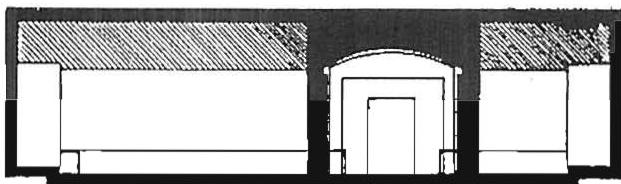

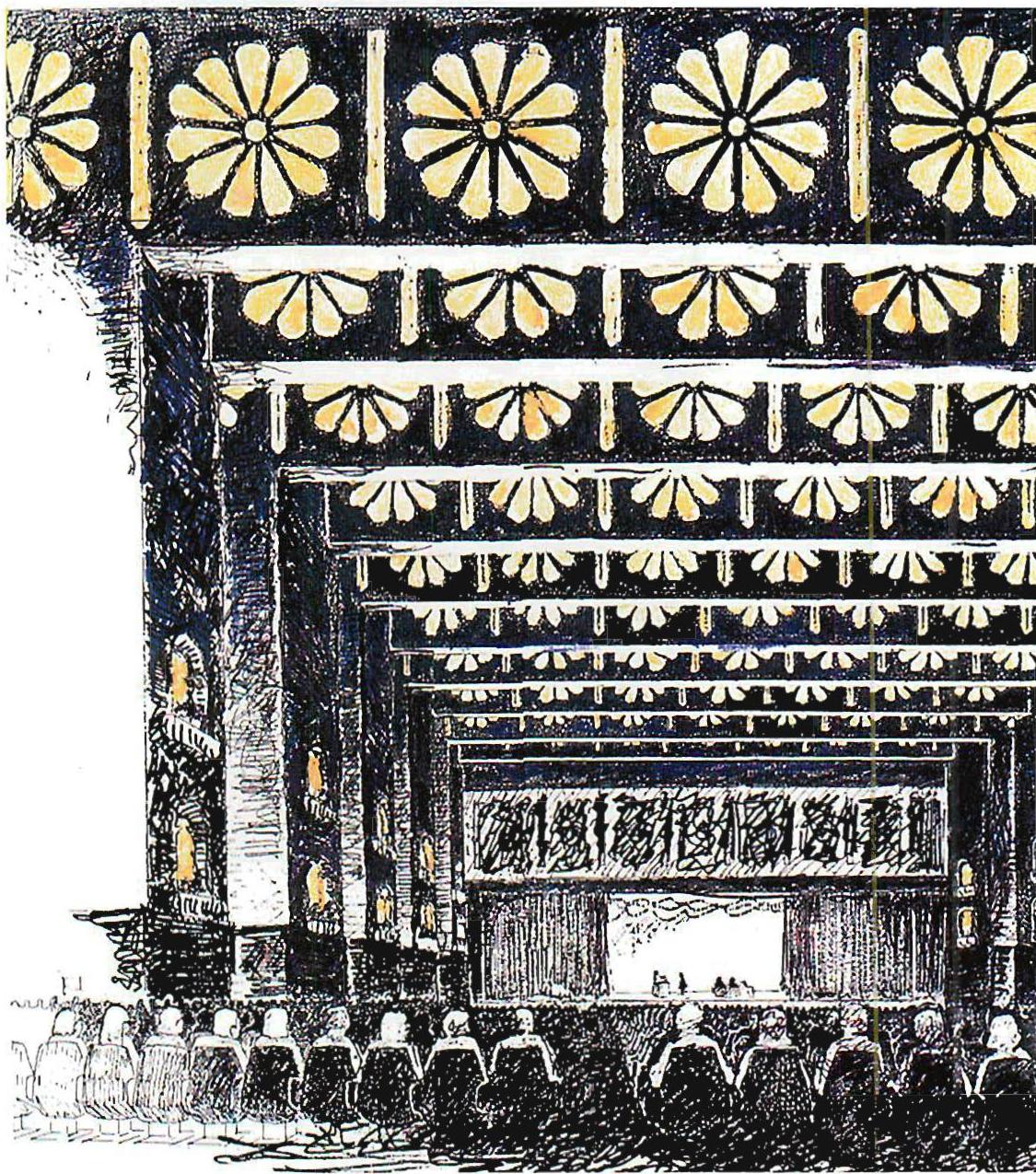

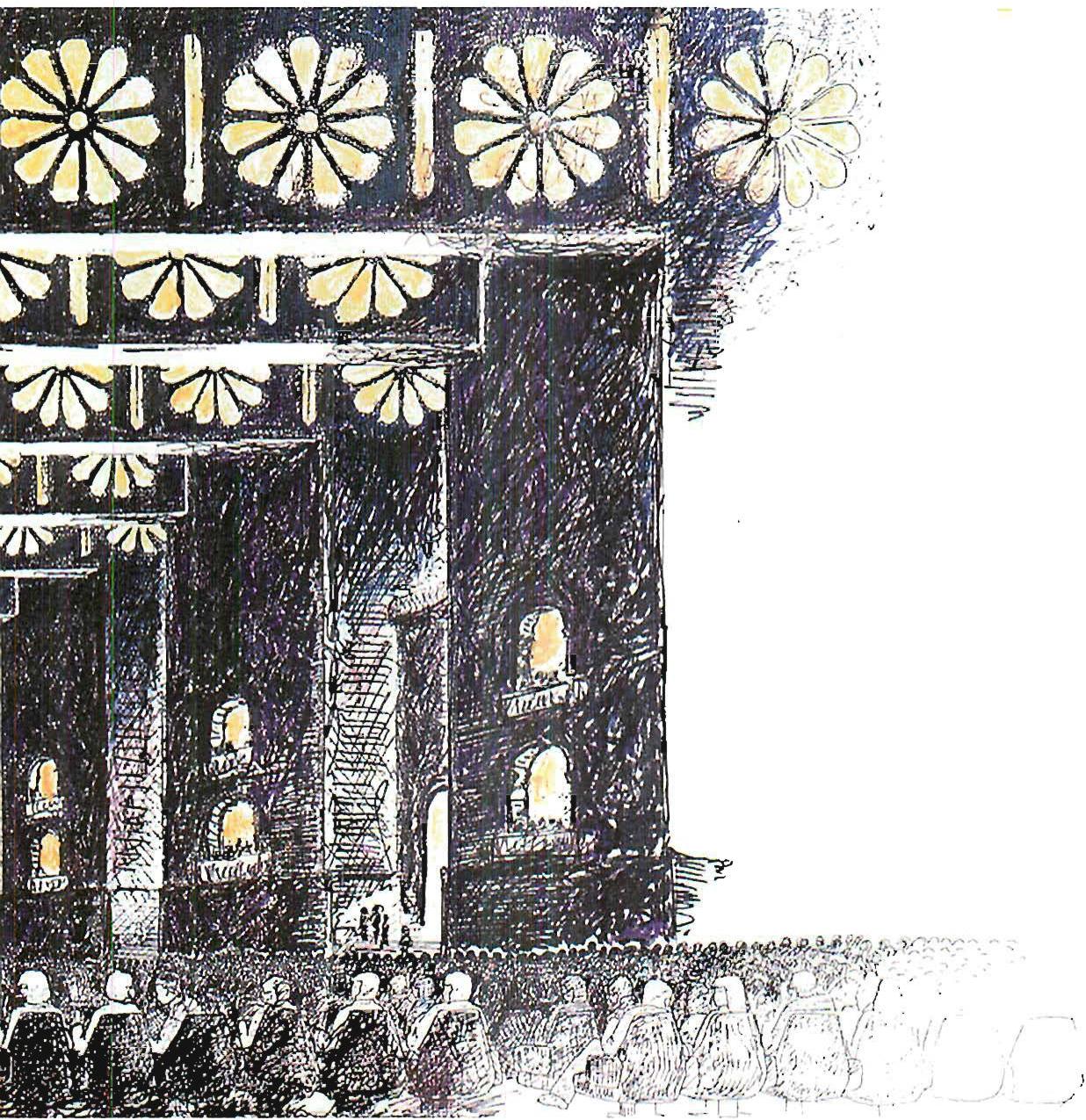

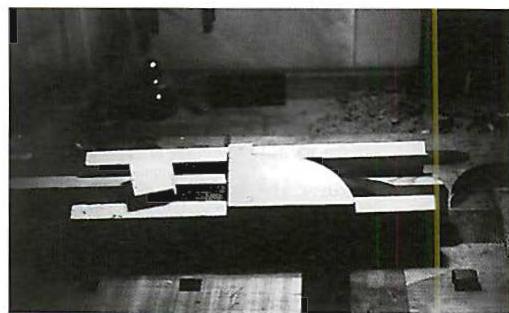

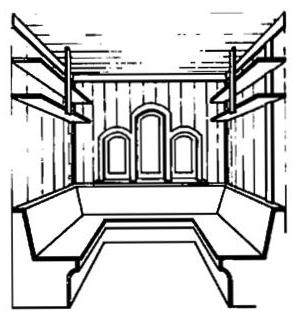

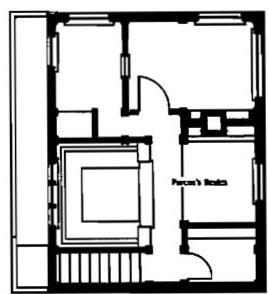

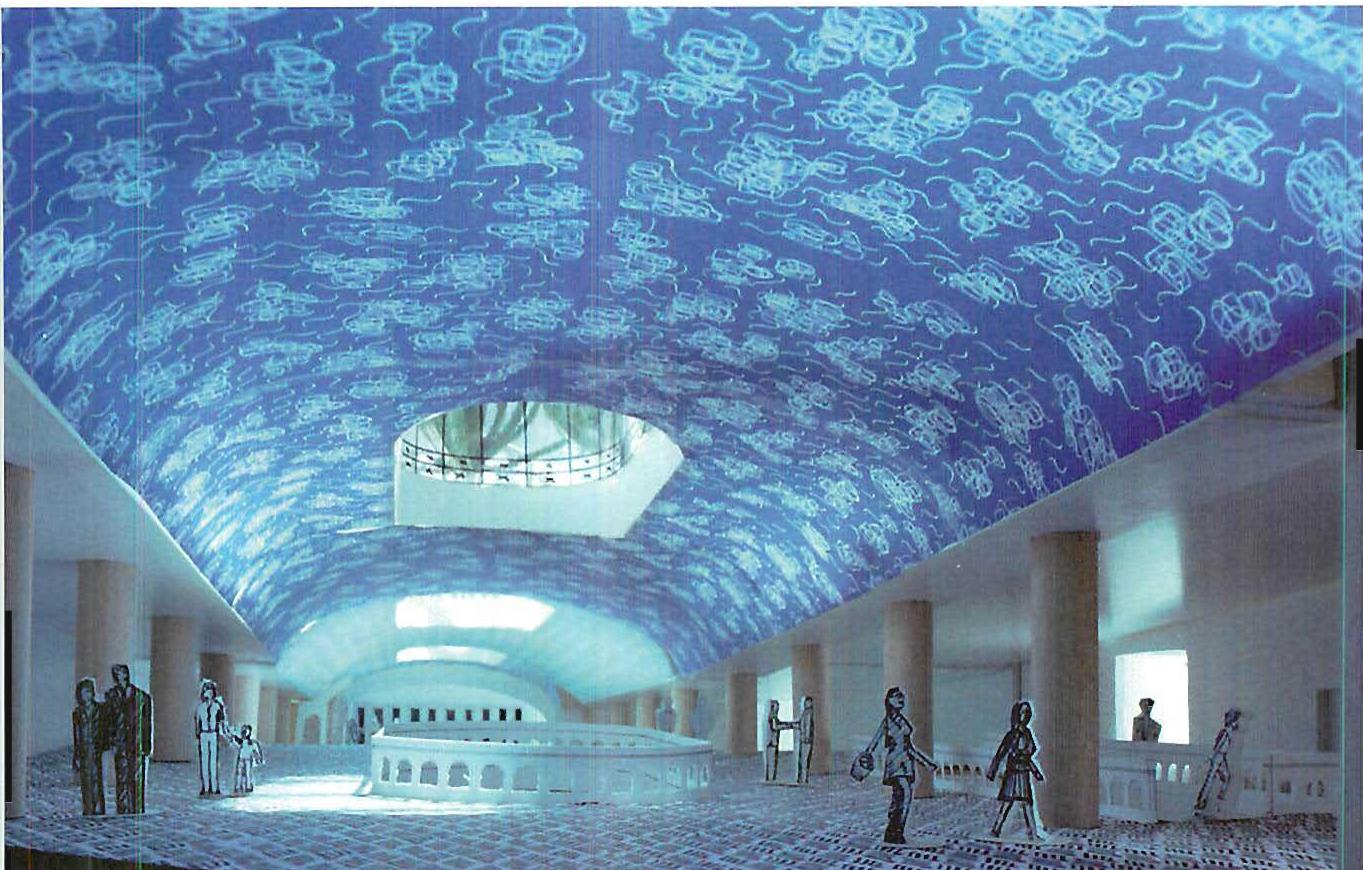

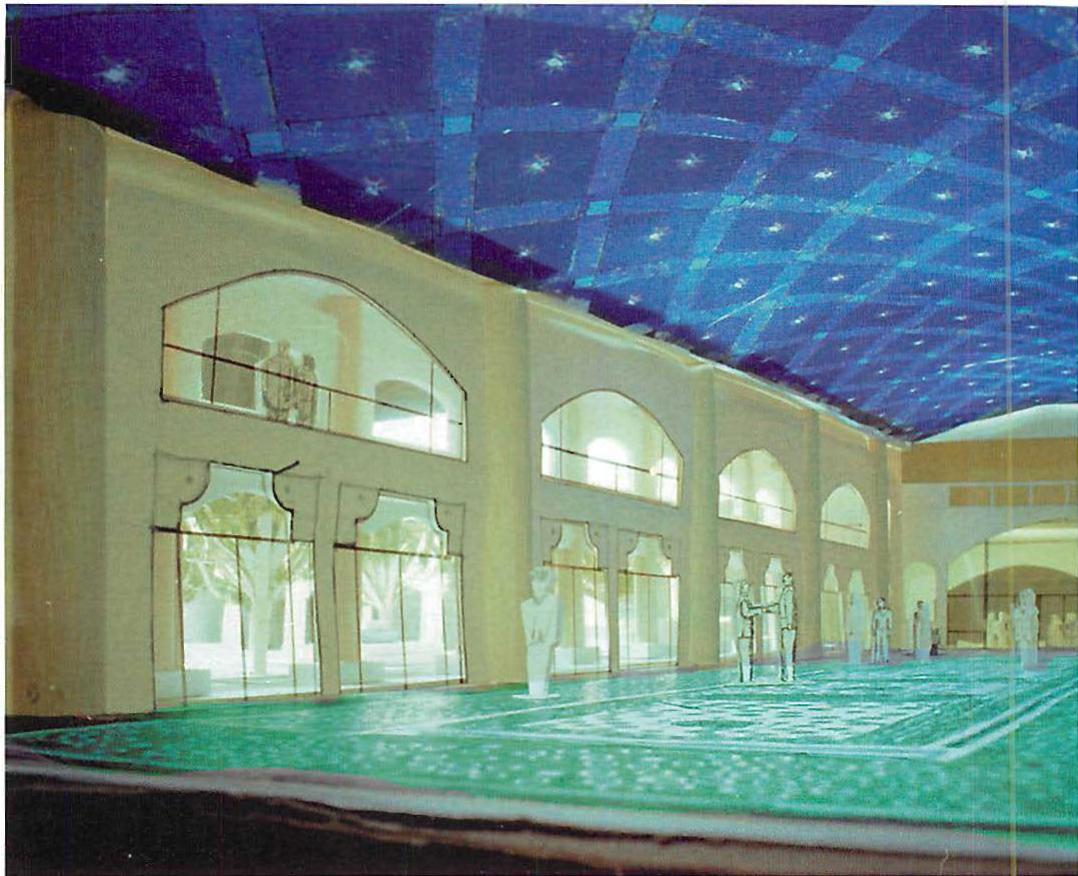

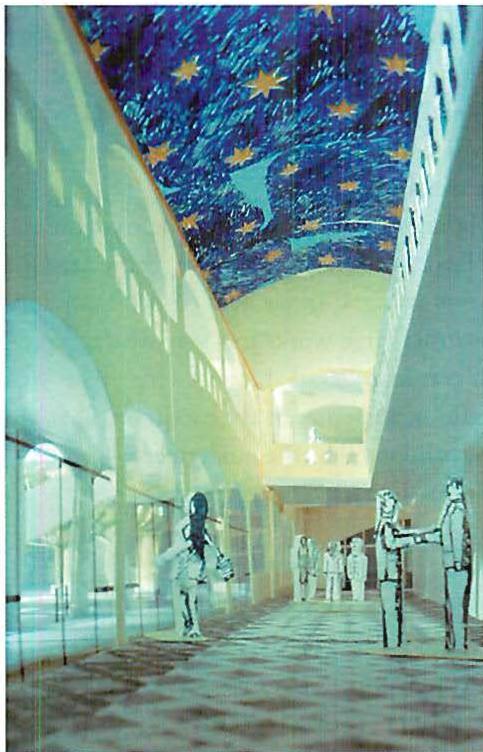

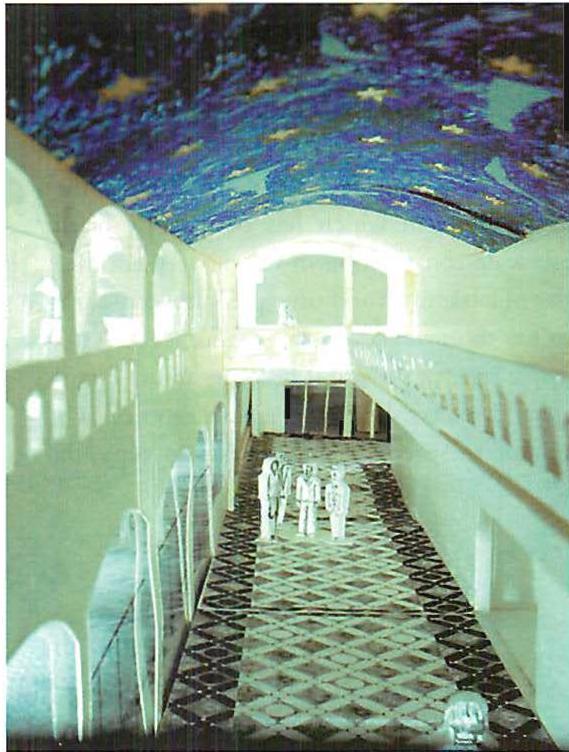

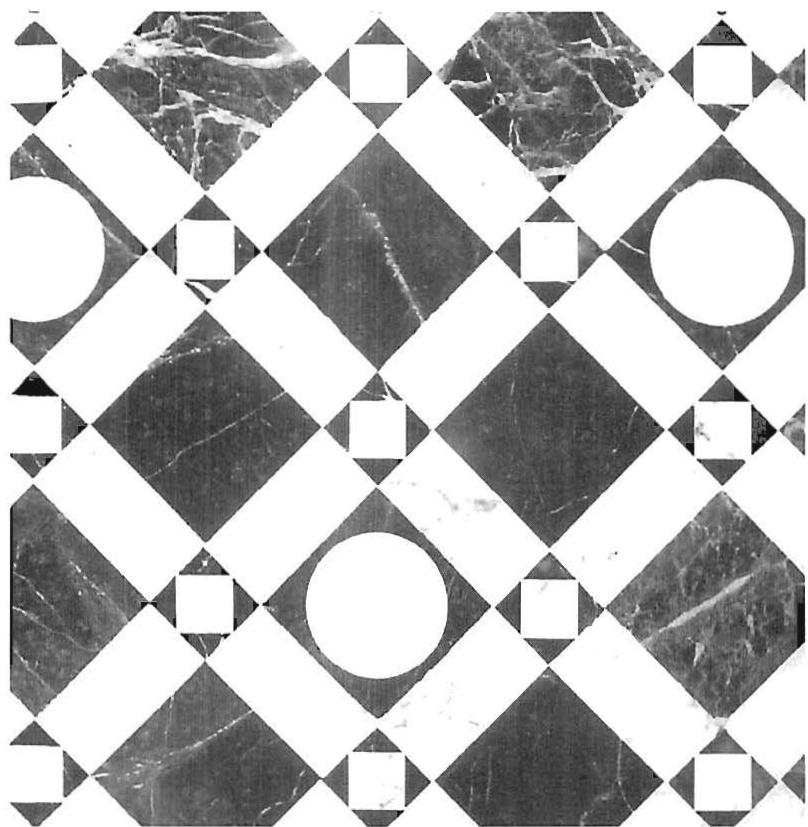

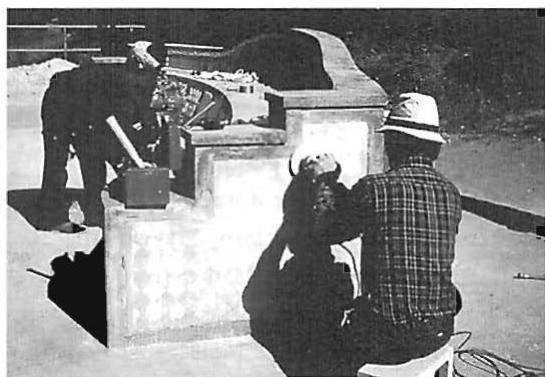

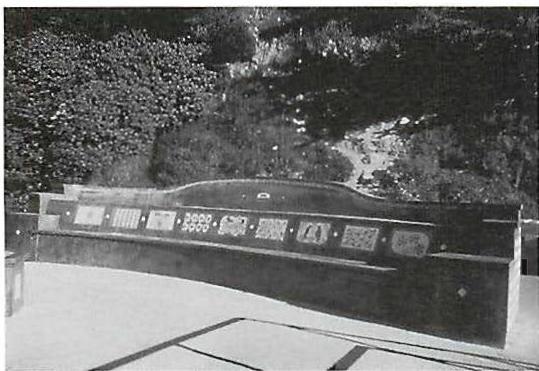

DESIGN FOR THE INTERIOR COURTYARD OF A CIVIC CENTER FOR THE CITY OF MOUNTAIN VIEW, CALIFORNIA

The building on the next two pages—a picture of the interior courtyard in a commissioned design for the Civic Center of Mountain View, California—shows an example of a large public project, conceived and designed within the framework of living processes. Again, all the steps needed to reach the design depicted here, depended on having the right sequence: patiently, one step at a time, elements—aspects of the whole—were introduced into the design, until it was complete, always, at each step, asking what fitted best, and what did most to preserve and enhance the structure of the whole that was already there.

Consider the following steps, which occurred during the making of this courtyard.

- The courtyard was located, first, by a vision of a dome arising from the place, the dome hovering over the street, and over the courtyard.

- The courtyard was located, next, in more detail and rough position, by relation to the street and to the park, forming a bridge between the two.

- Next the size and height were fixed: first the size—formed by walking out the proper diameter, standing in that place on the land.

- Then the height, 3 stories, worked out partly by reference to the area of office space needed, but more important, worked out as a height, felt by people in the courtyard, hovering above them, and giving dignity to the green dome.

Next the covered arcade, depicted — generous, high and wide, and facing the dome.

Then the color of the whole, its yellow plastered wall.

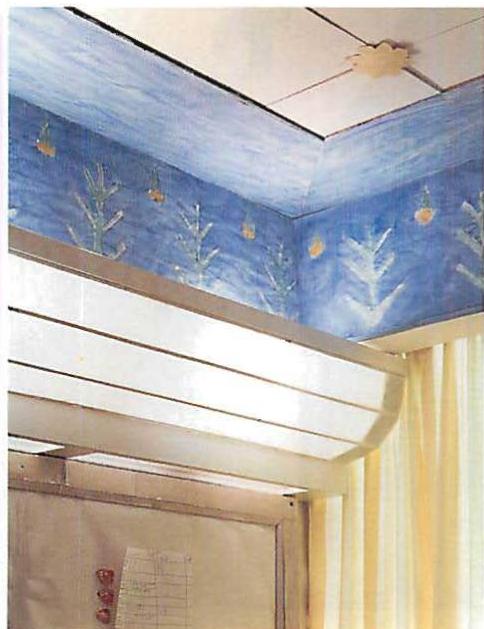

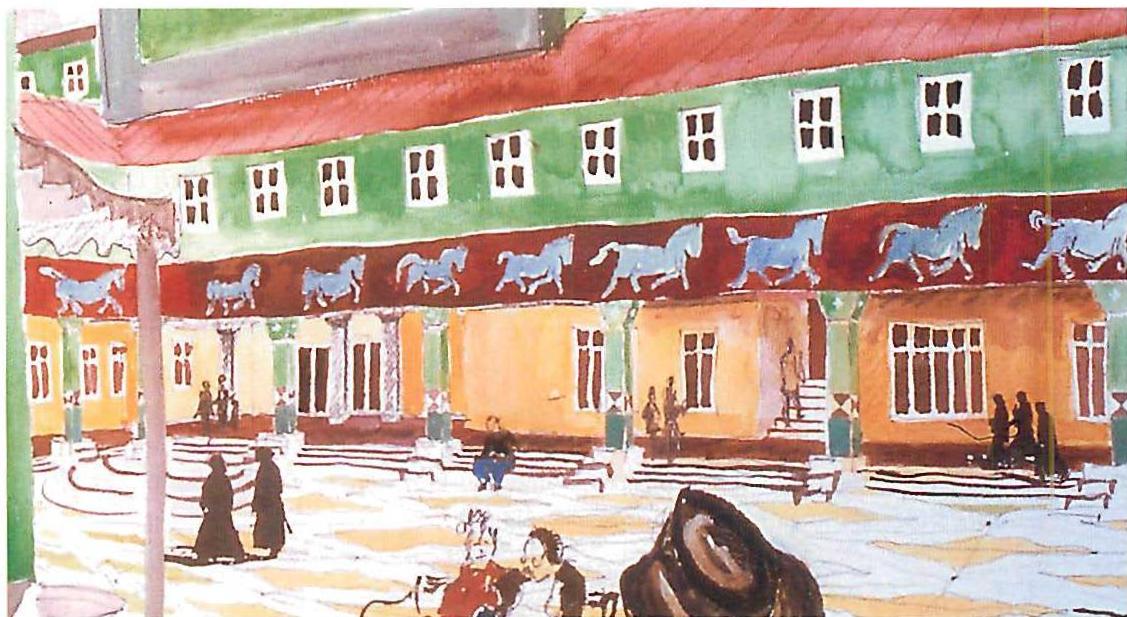

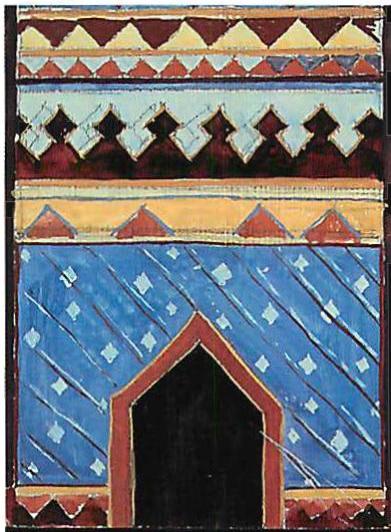

Then the blue horses, a frieze of huge ceramic horses all around, dominating the feeling, subsidiary to the dome

Then the paving, alternating with grass, worked out on a model, and once again sized by walking in the real place and deciding the 'just-right' size of the bits of lawn and alternating bits of stone and concrete.

Further details of this building and its courtyard are given on pages 109-11.

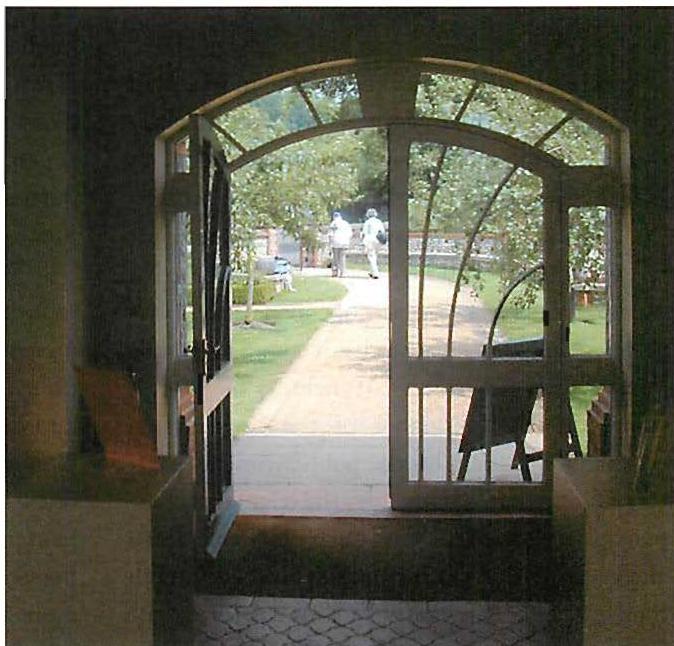

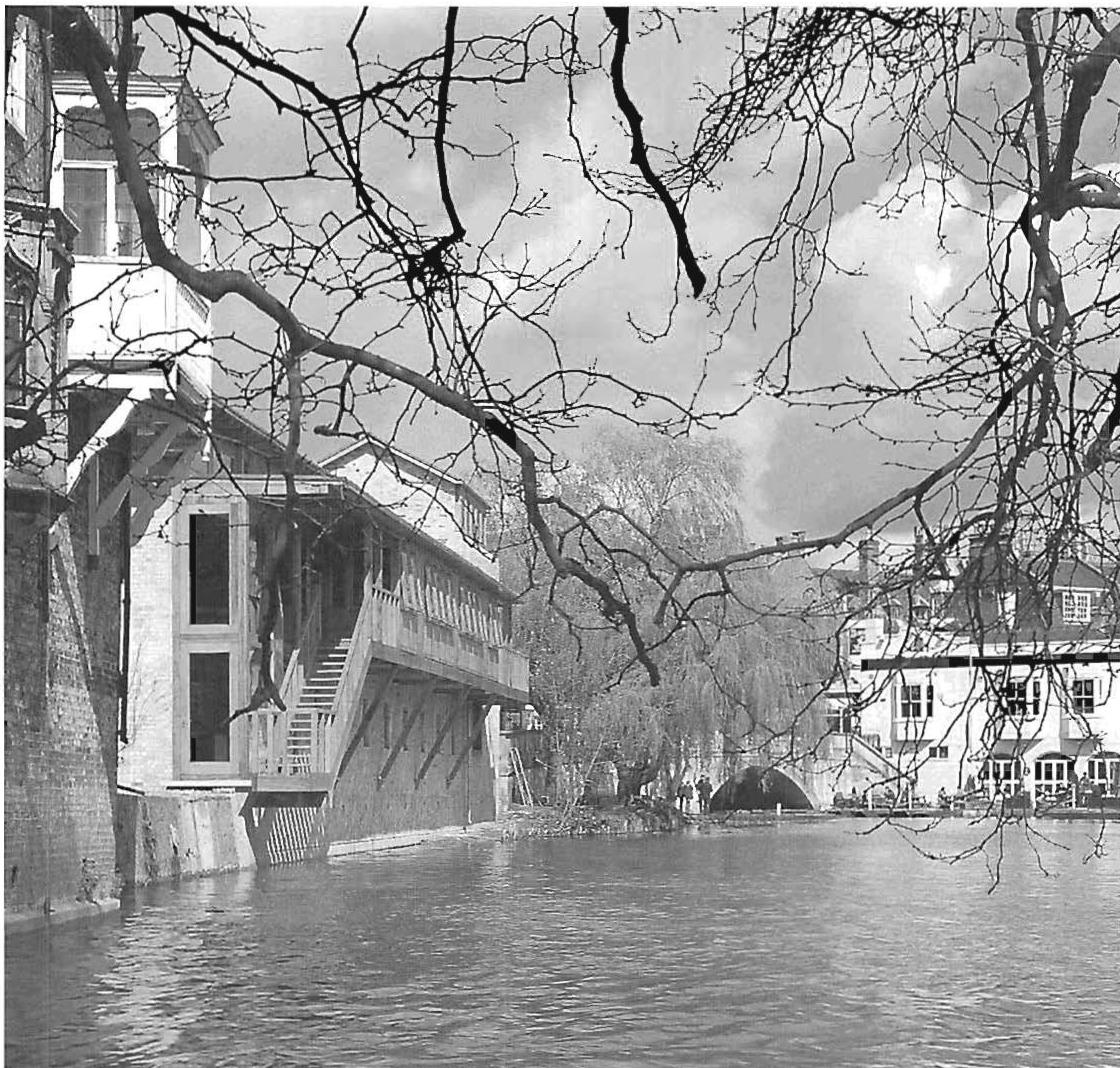

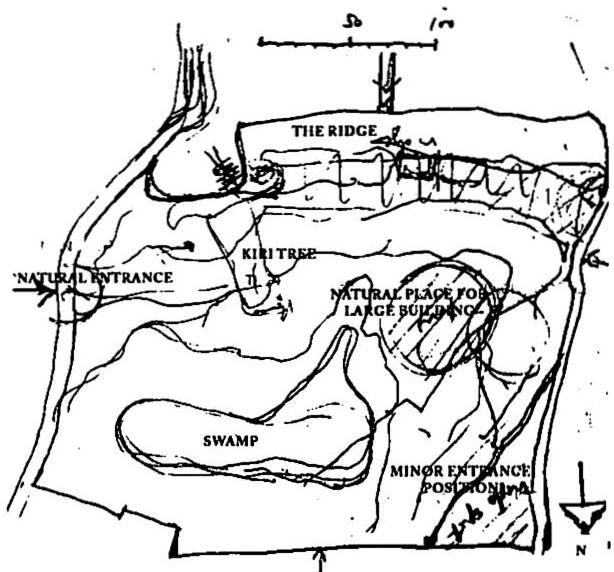

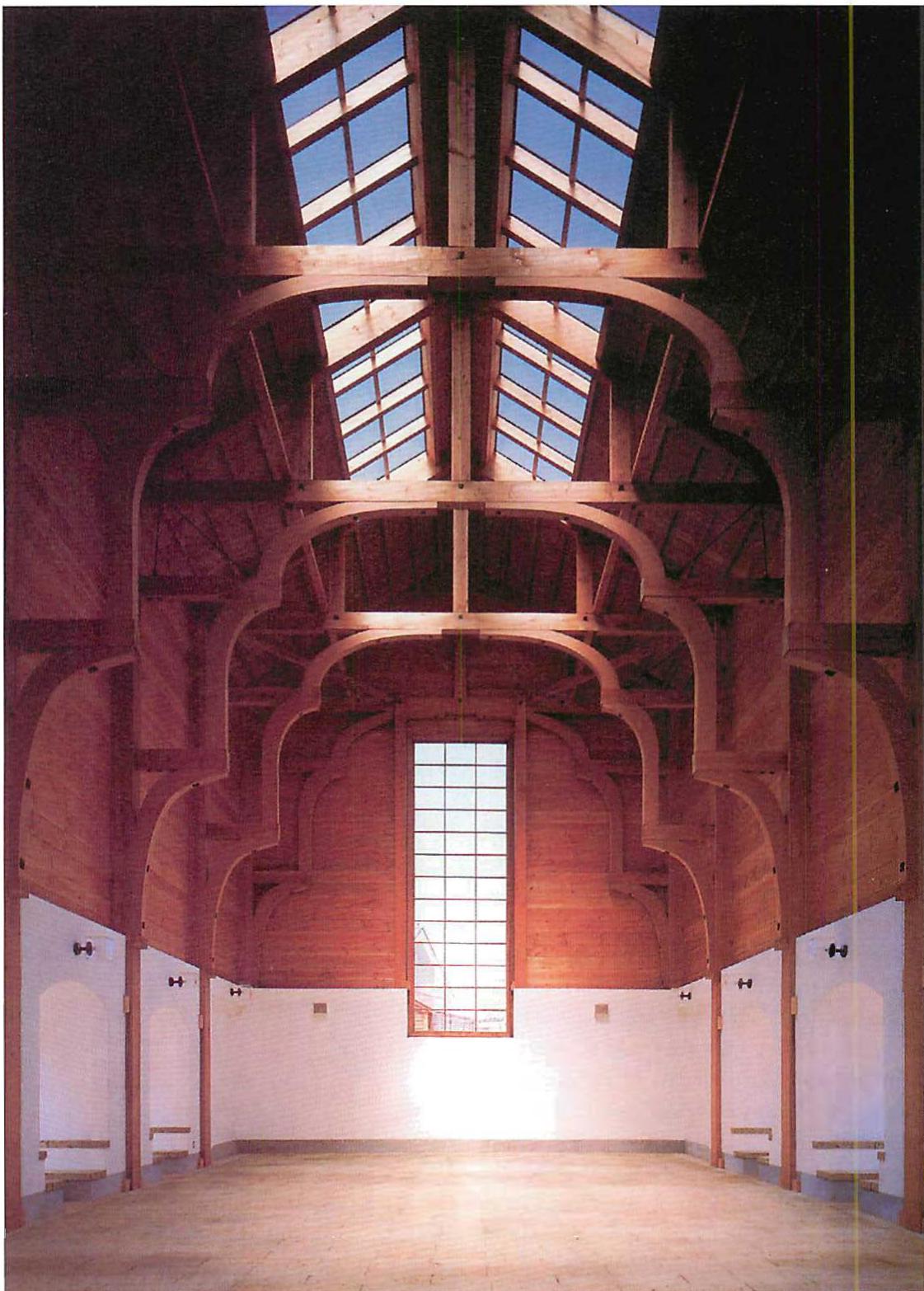

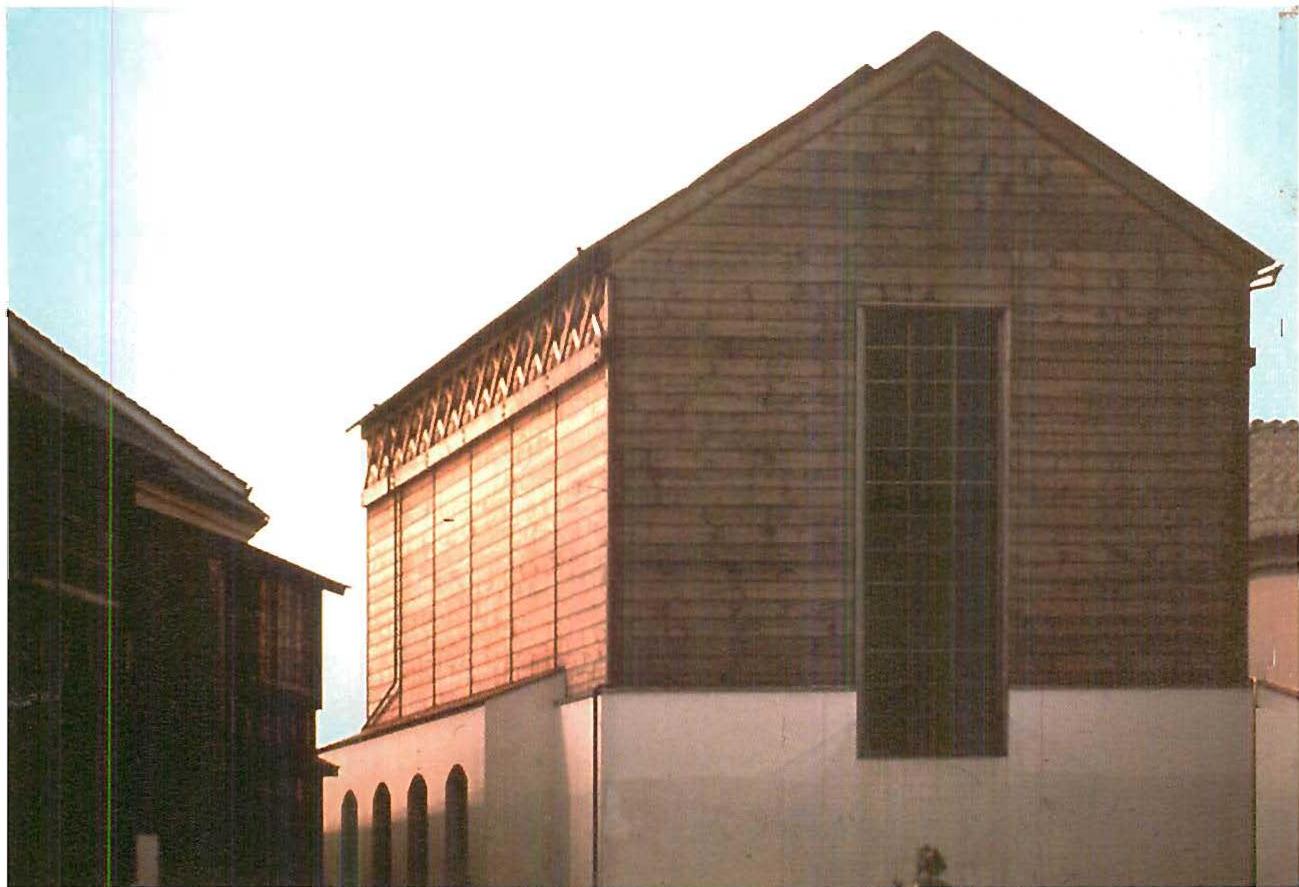

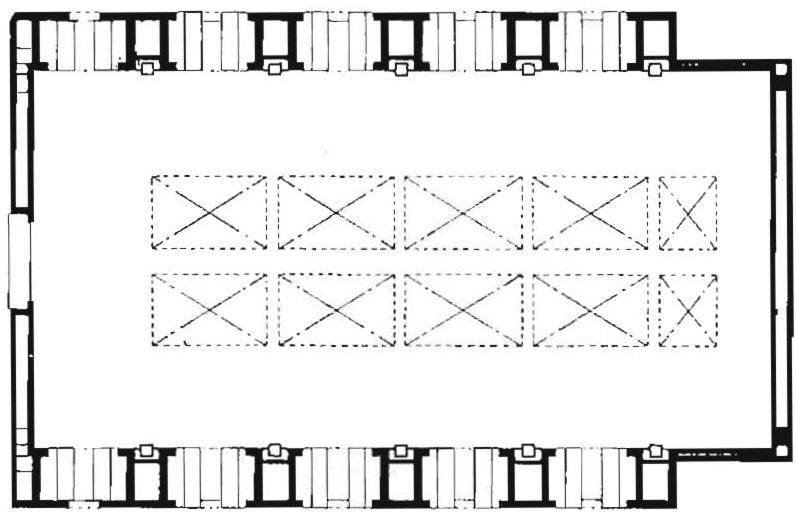

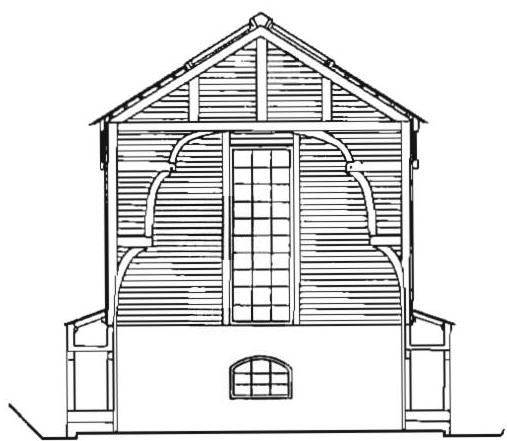

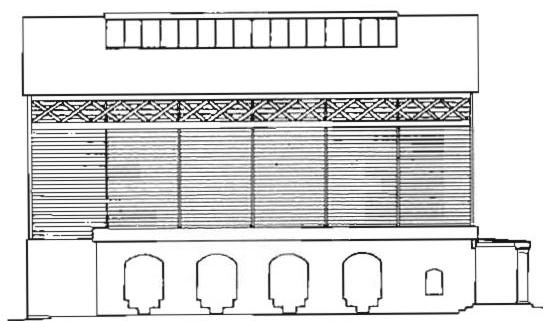

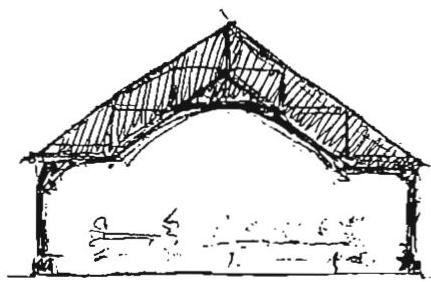

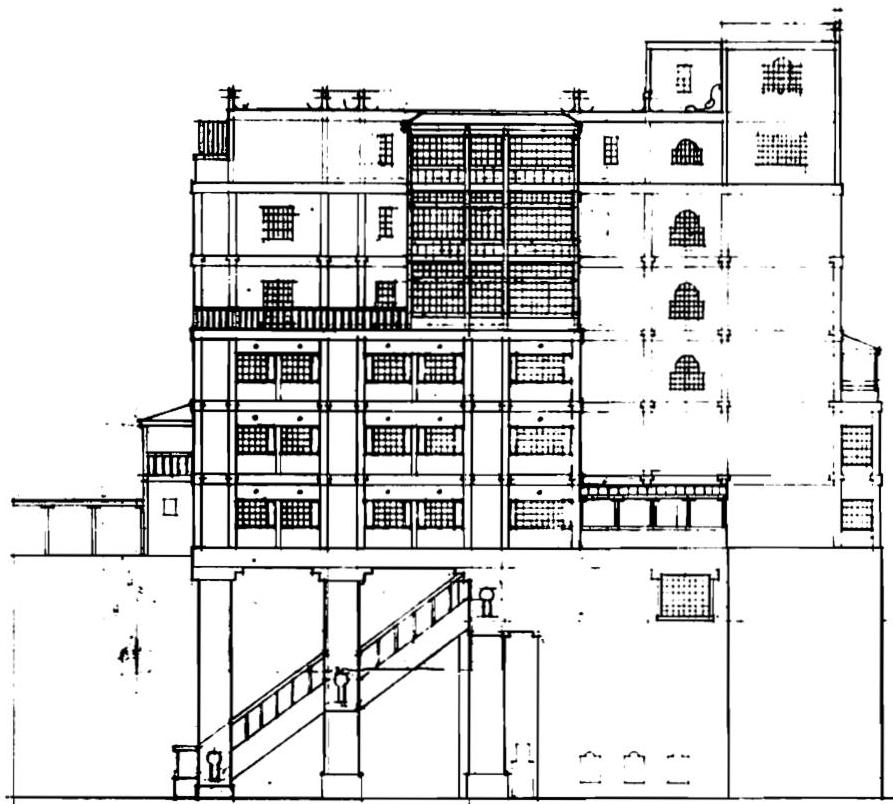

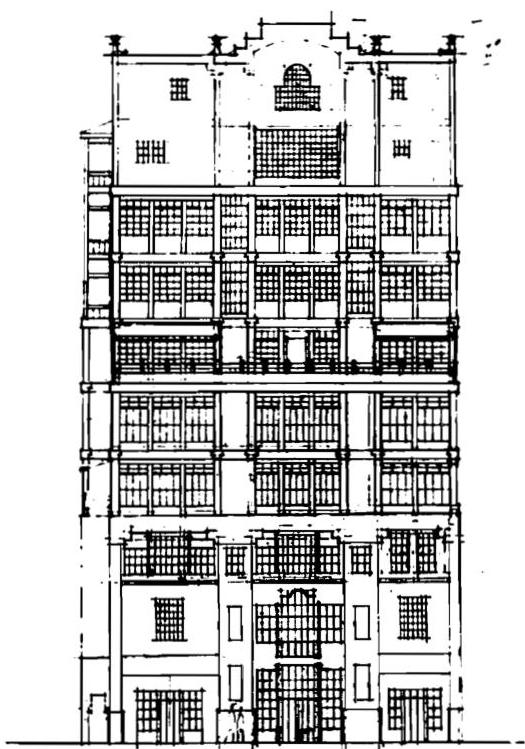

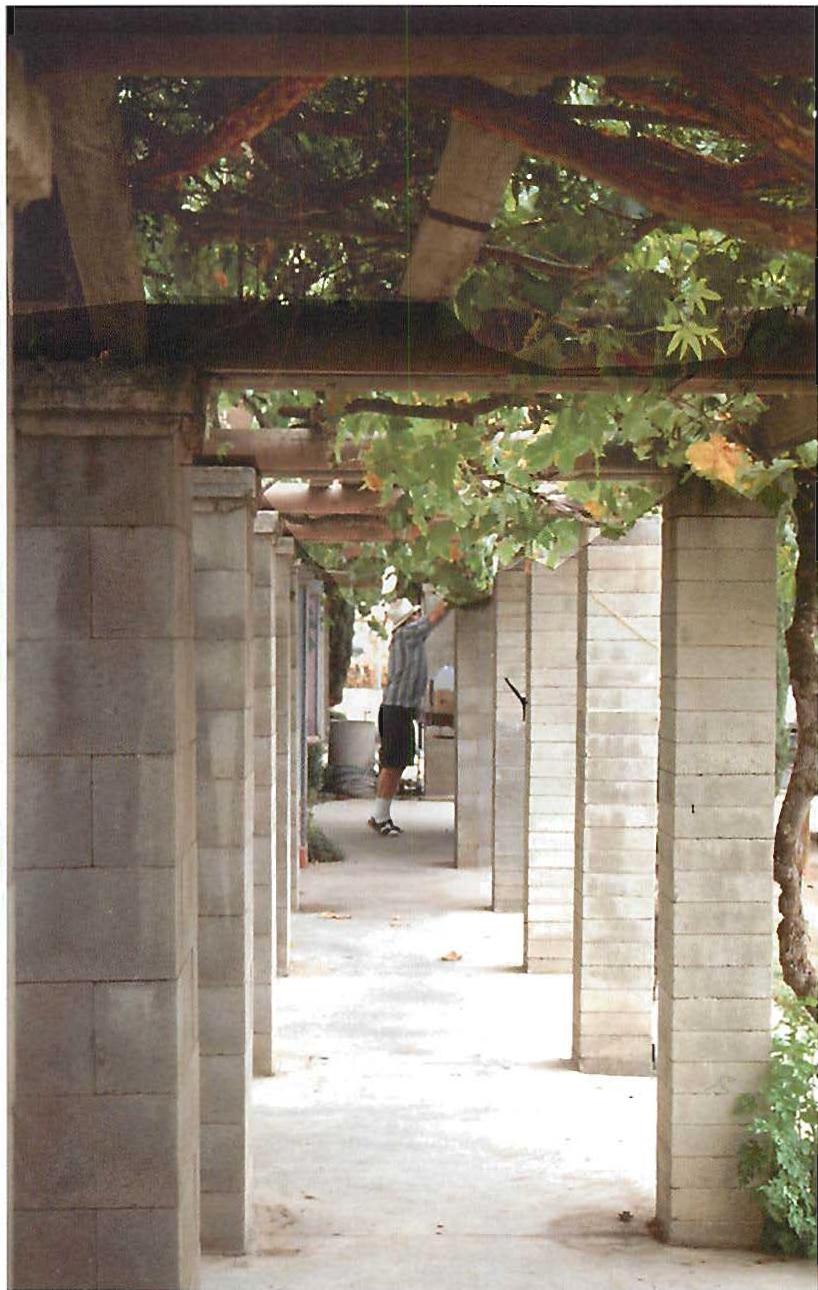

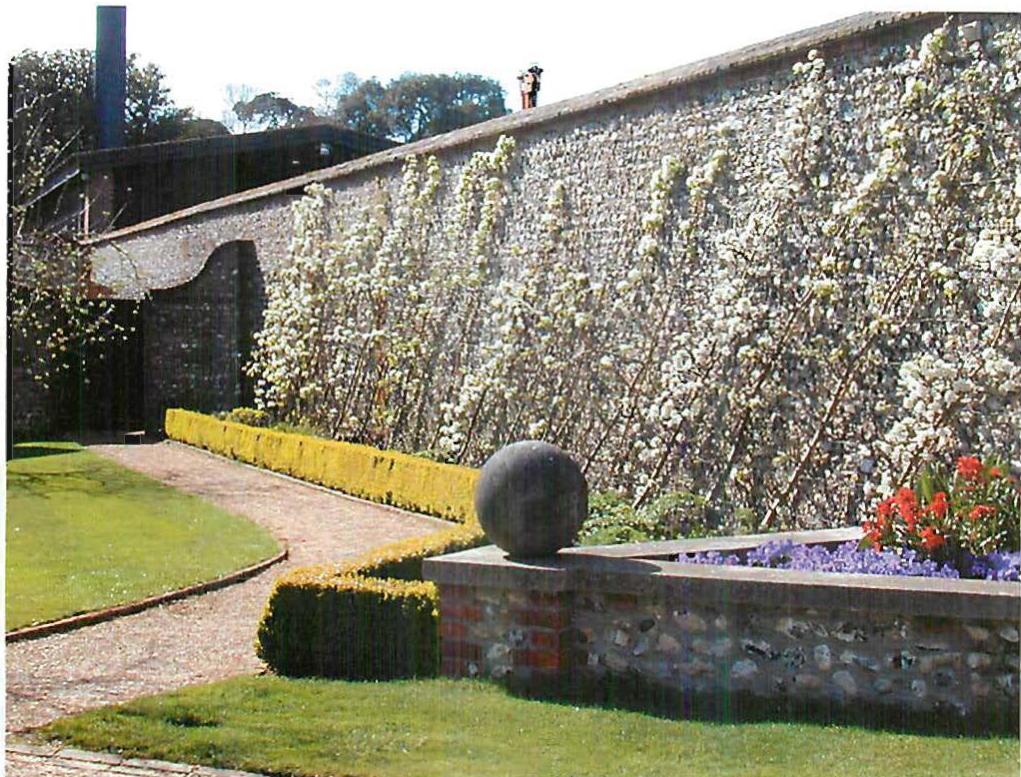

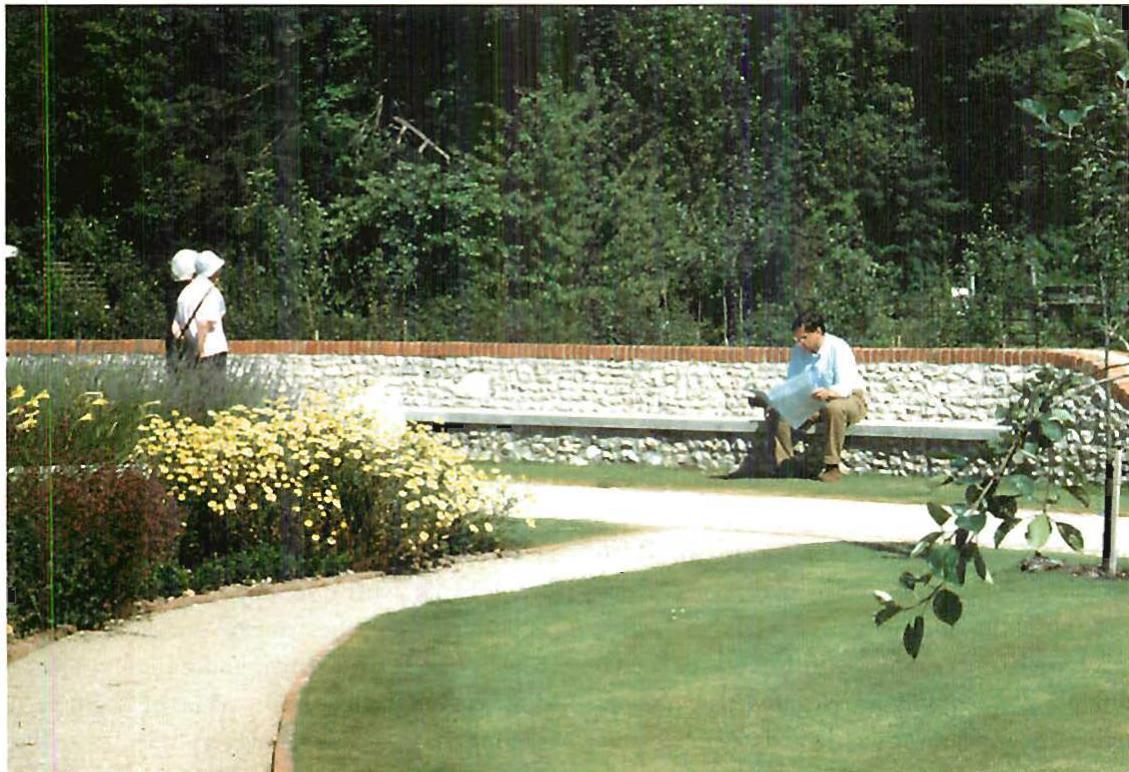

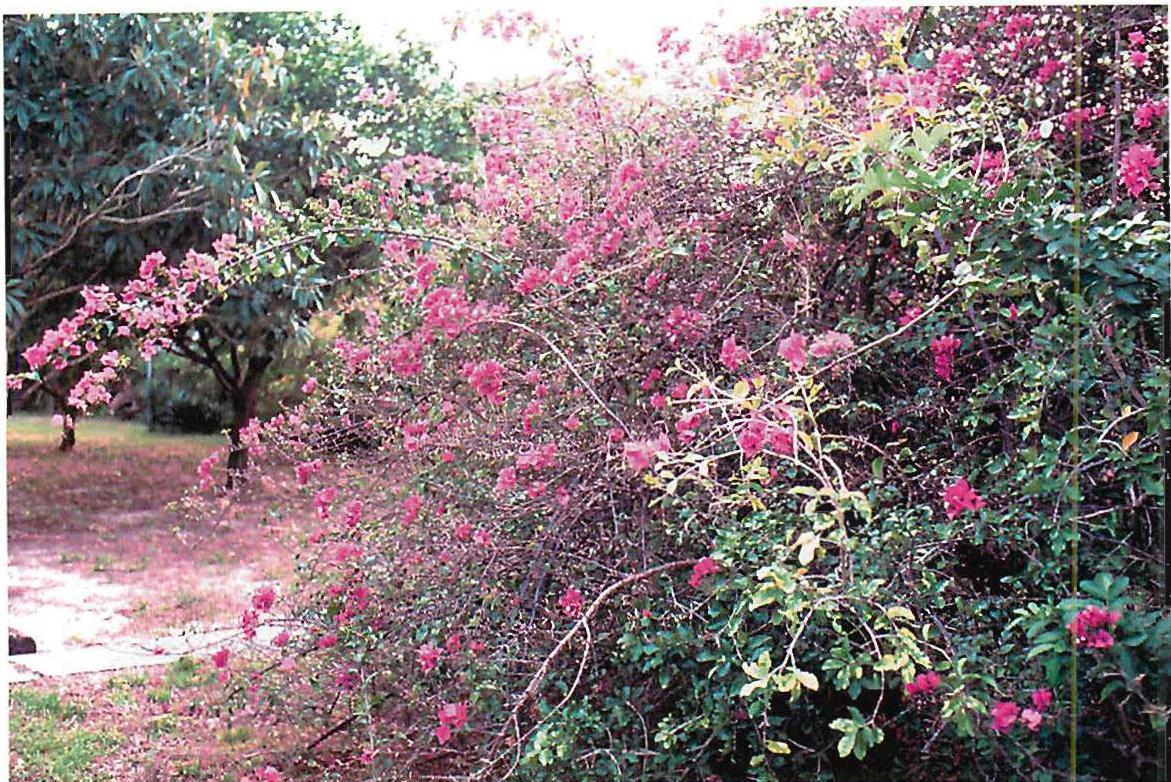

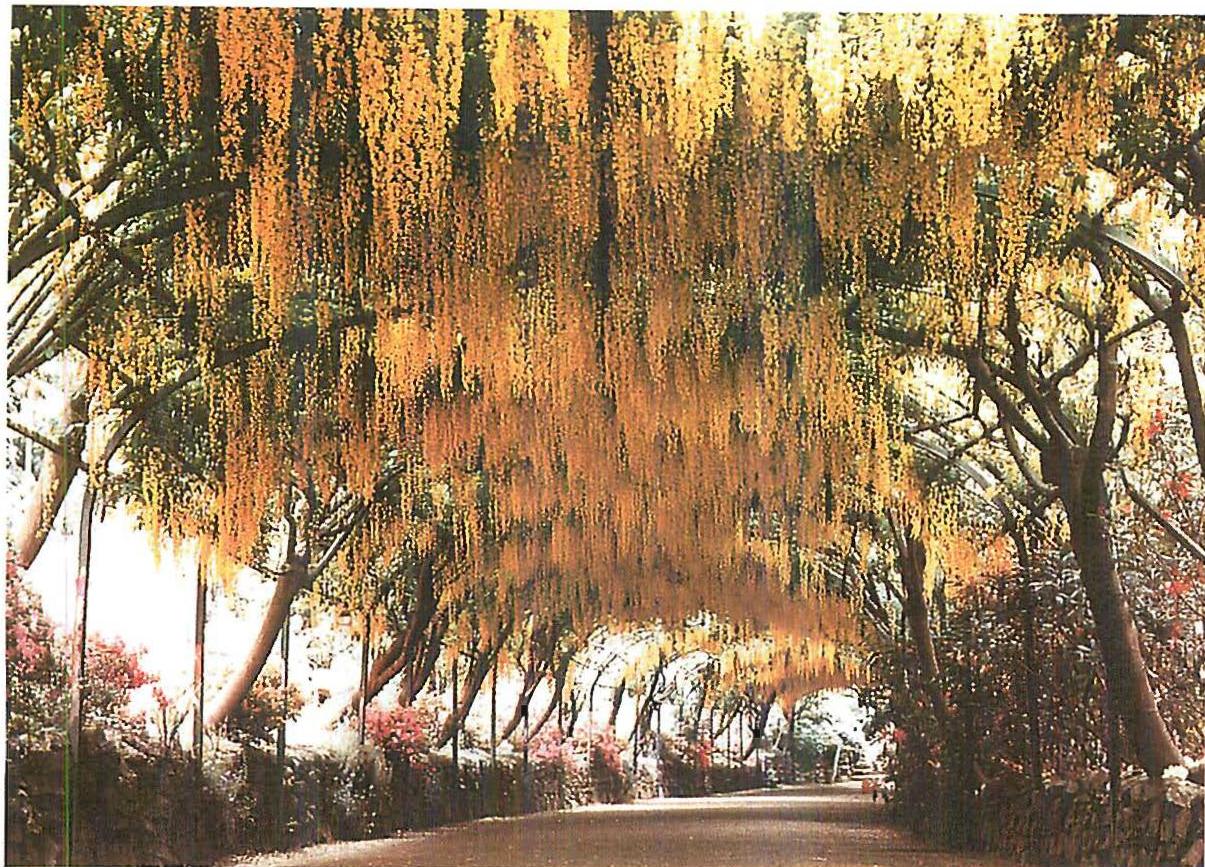

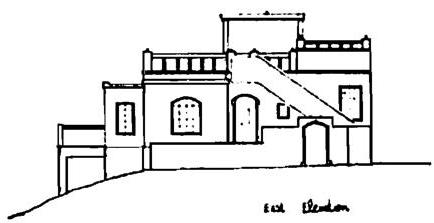

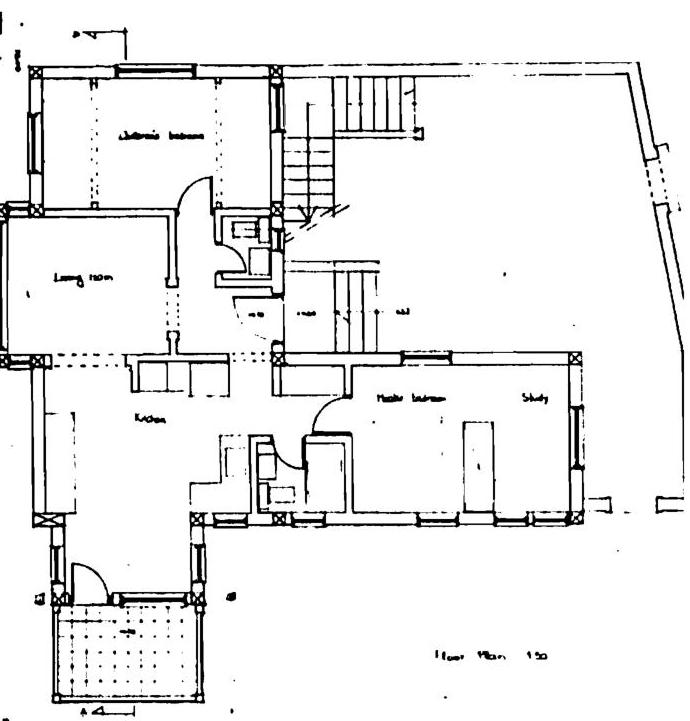

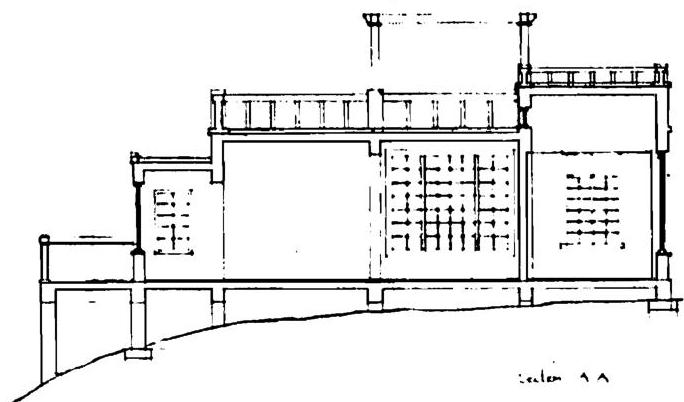

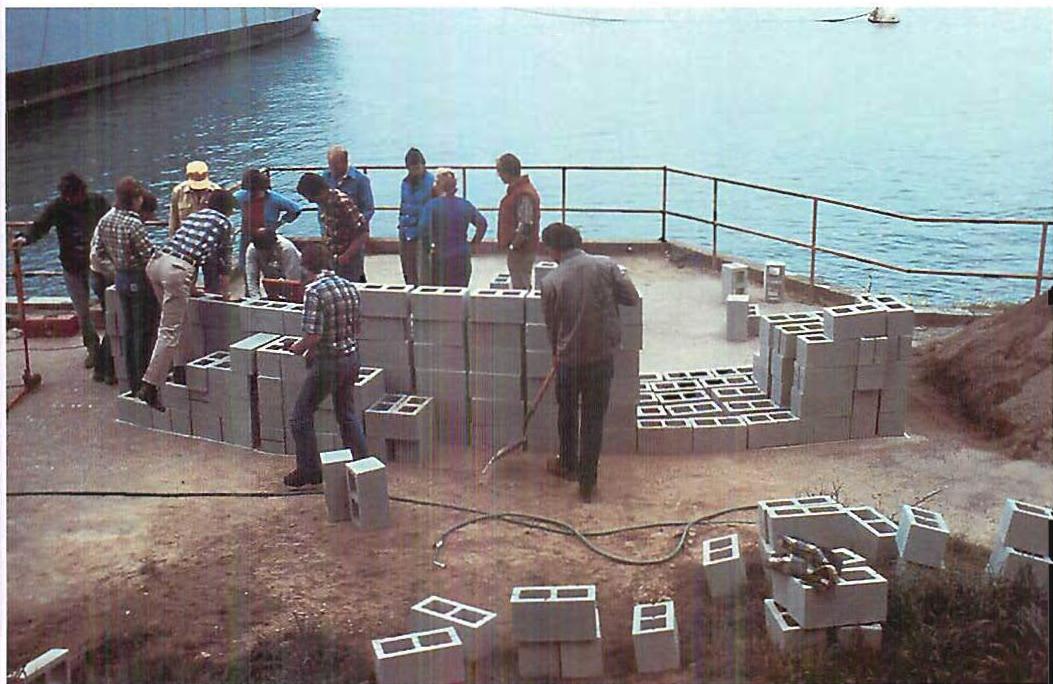

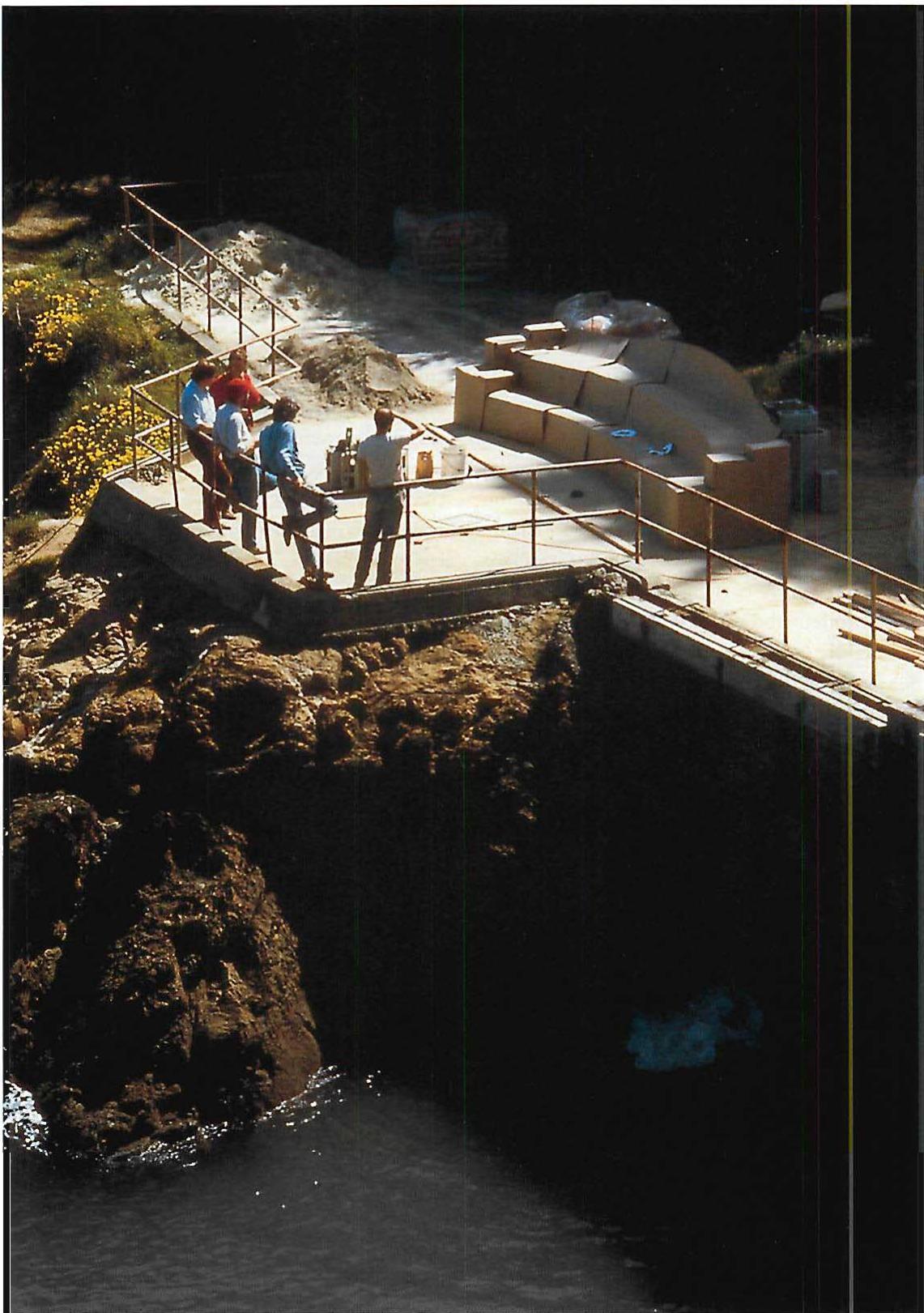

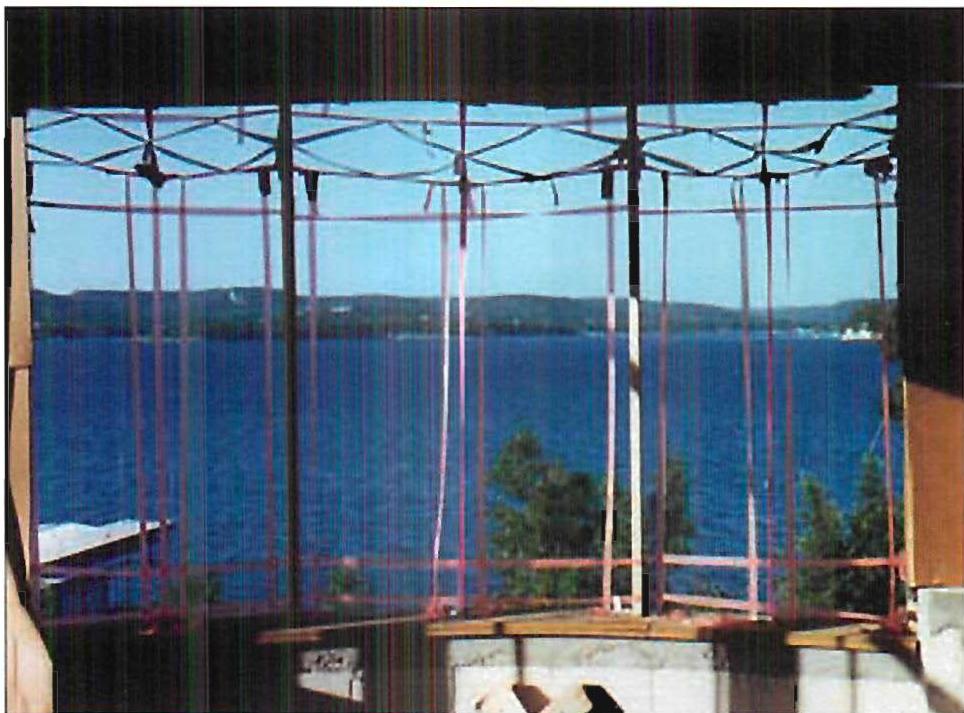

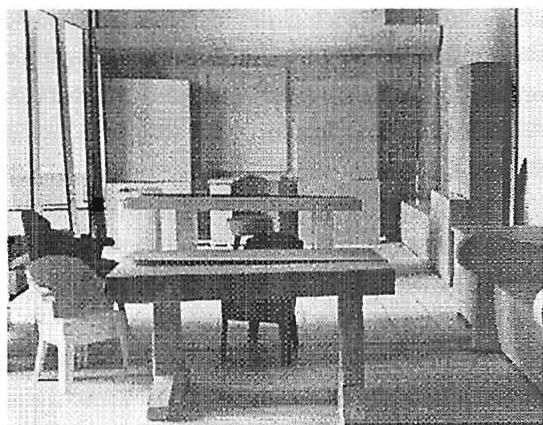

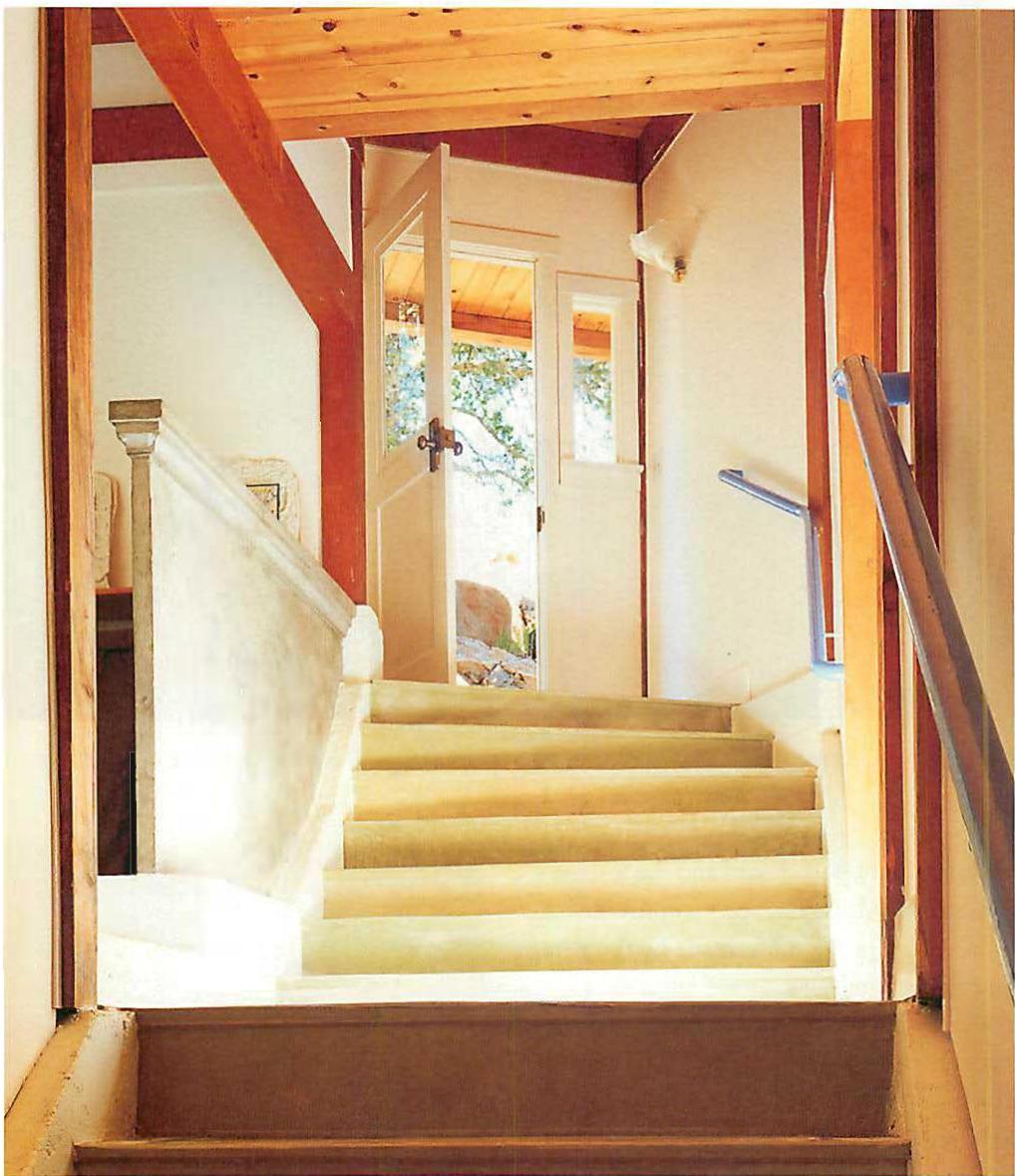

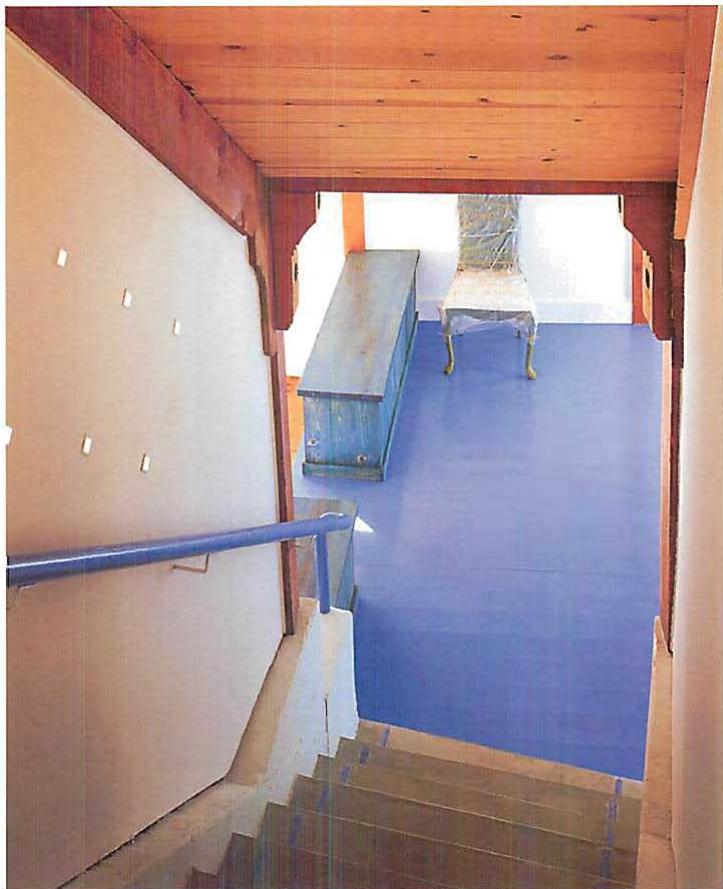

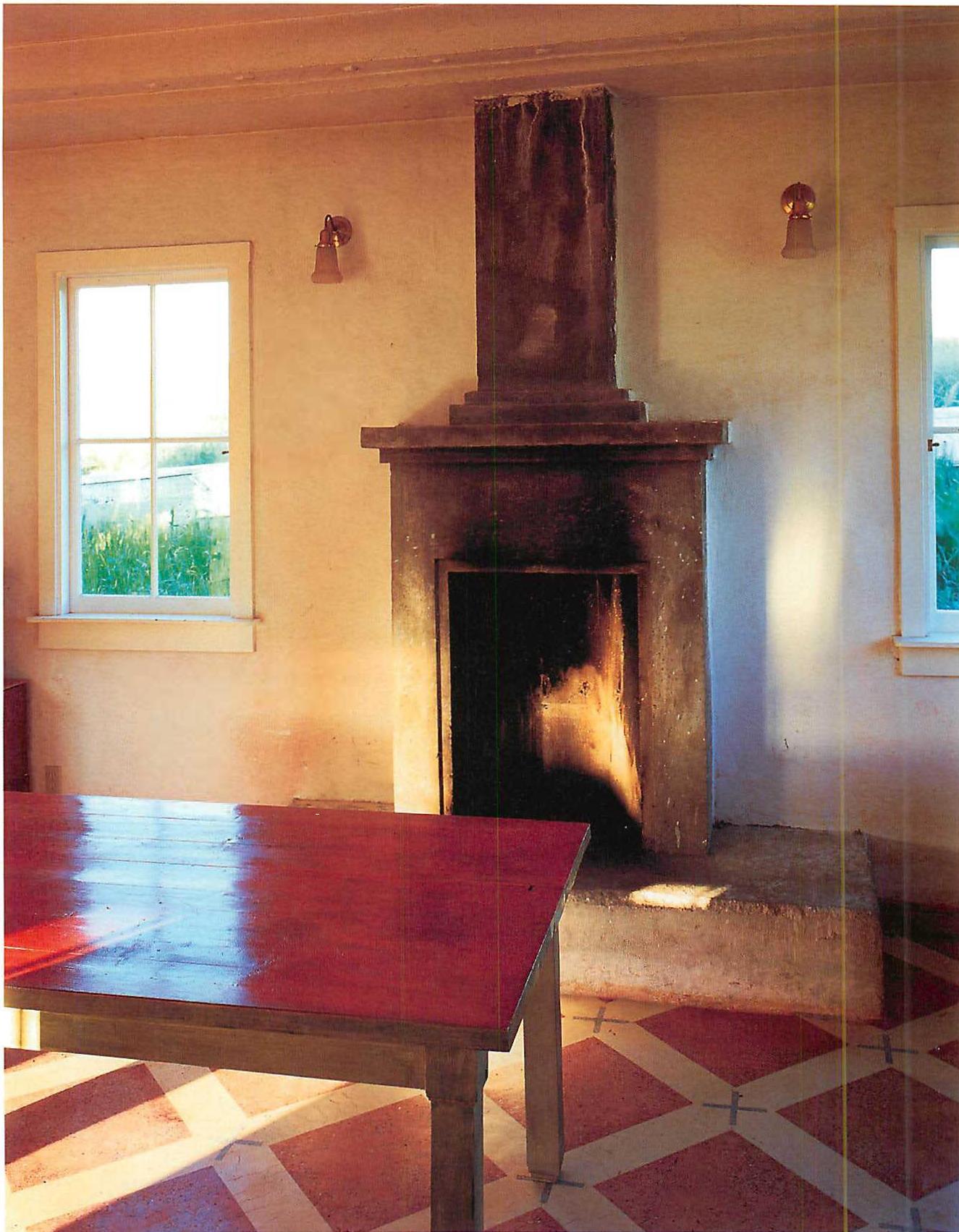

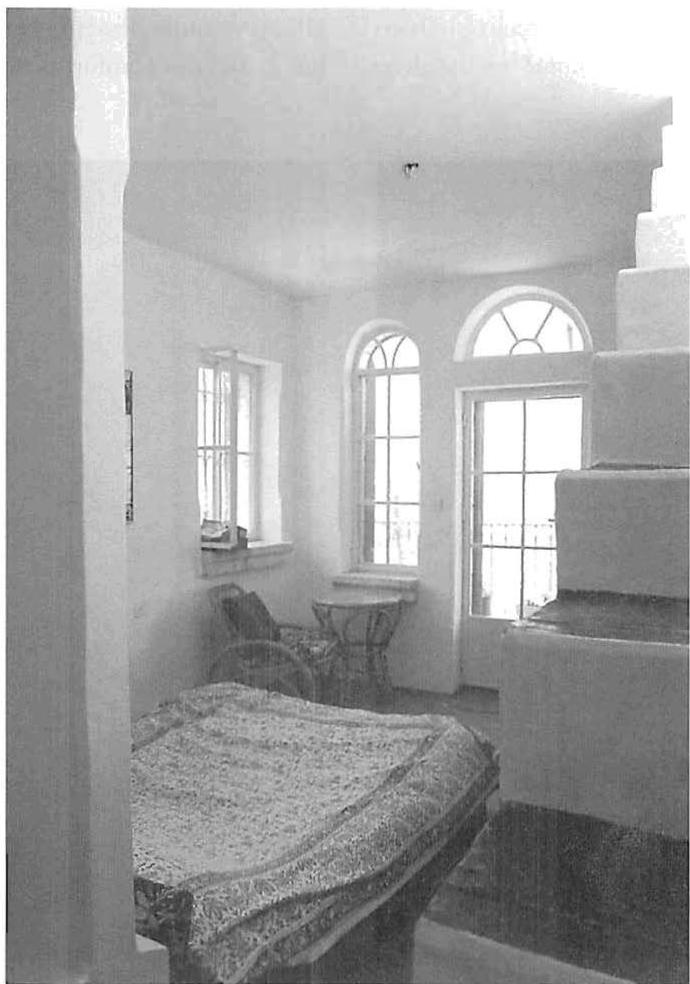

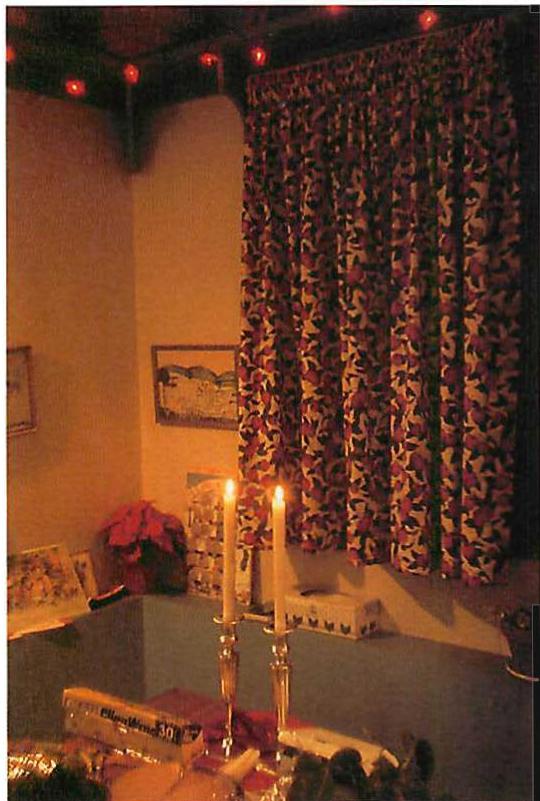

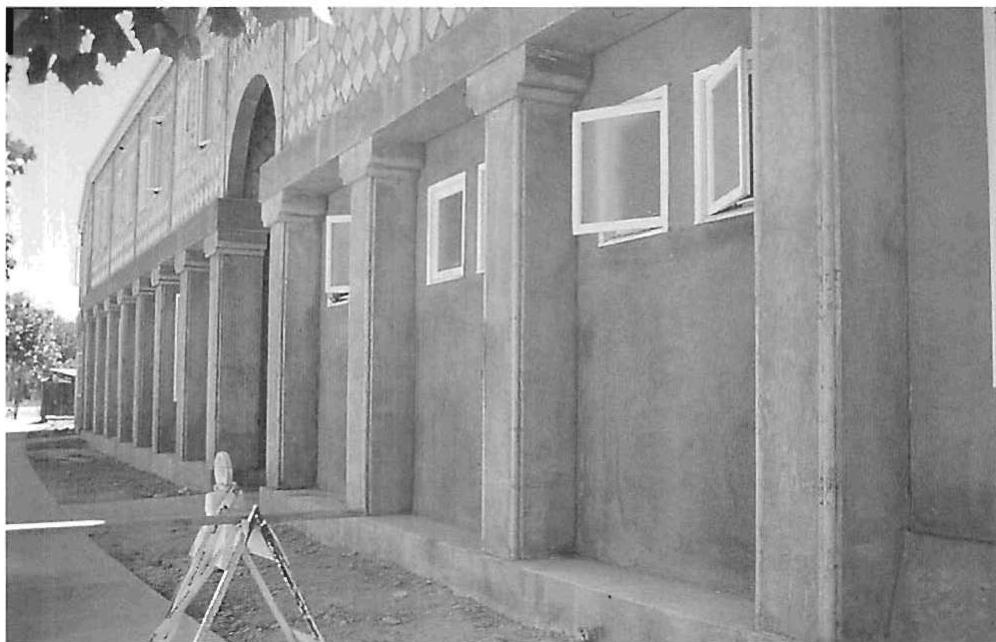

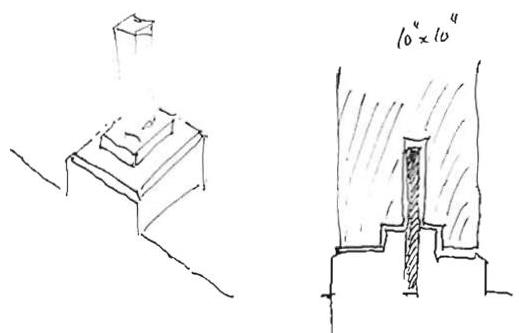

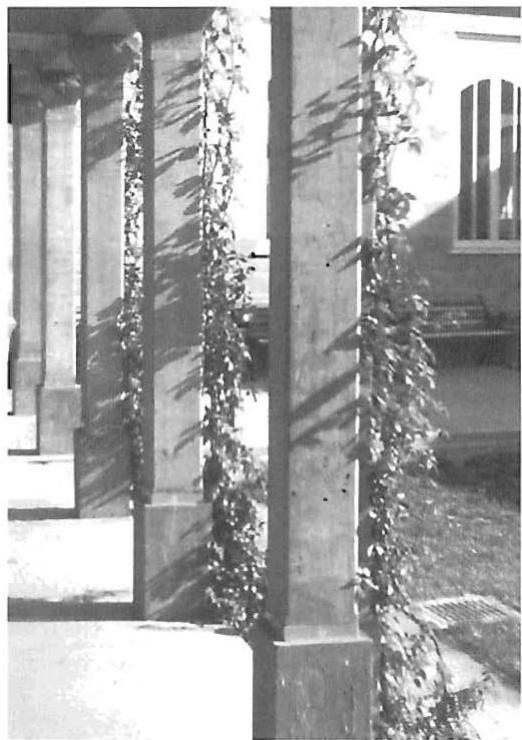

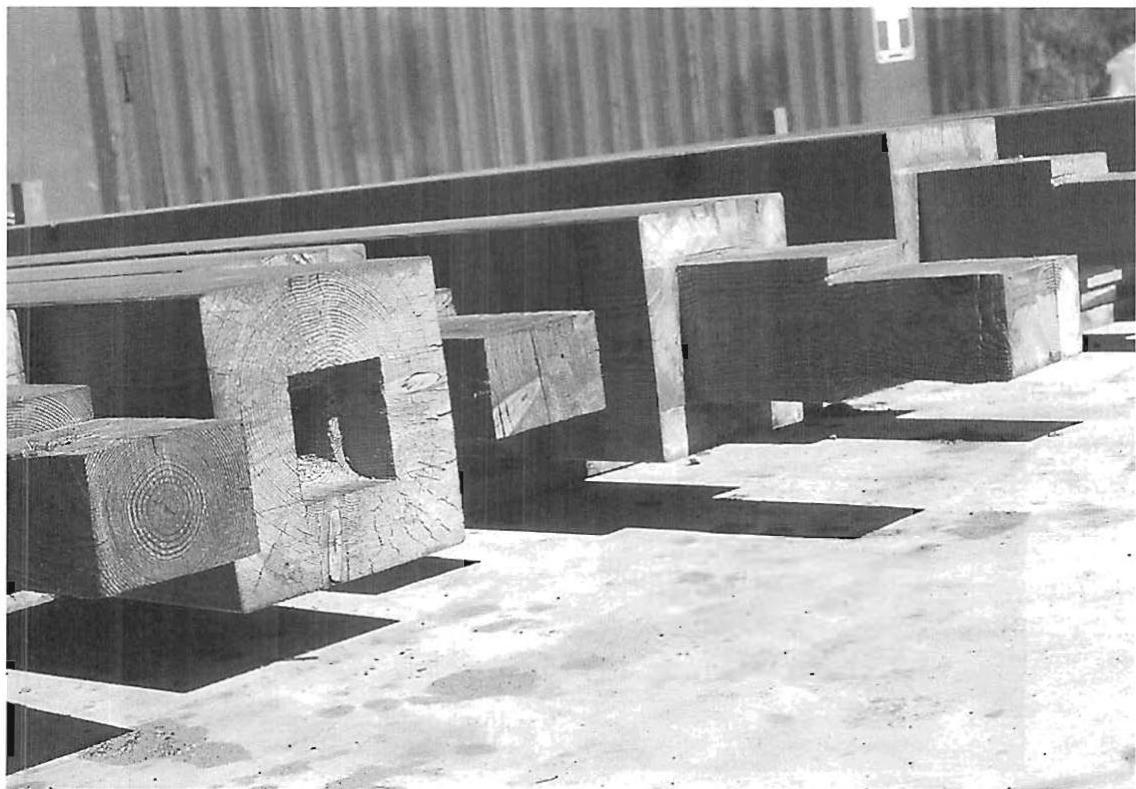

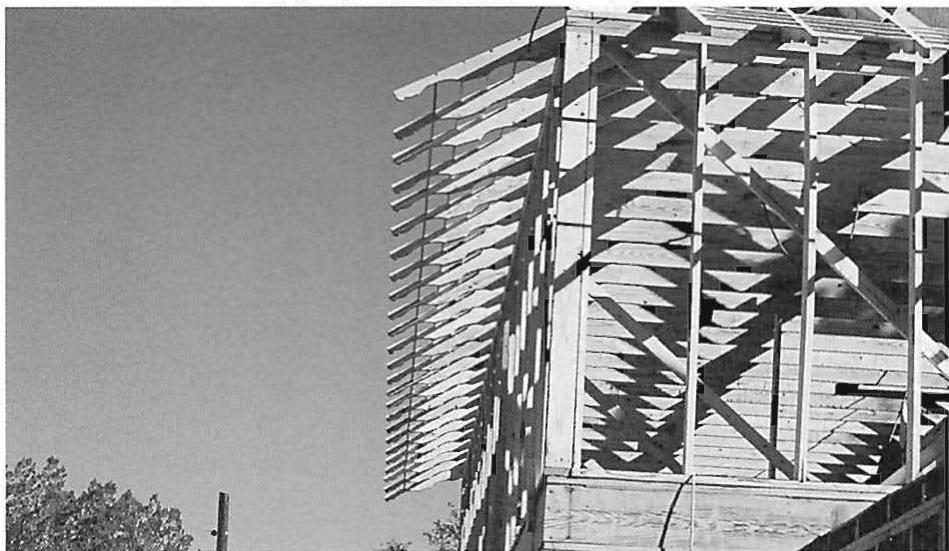

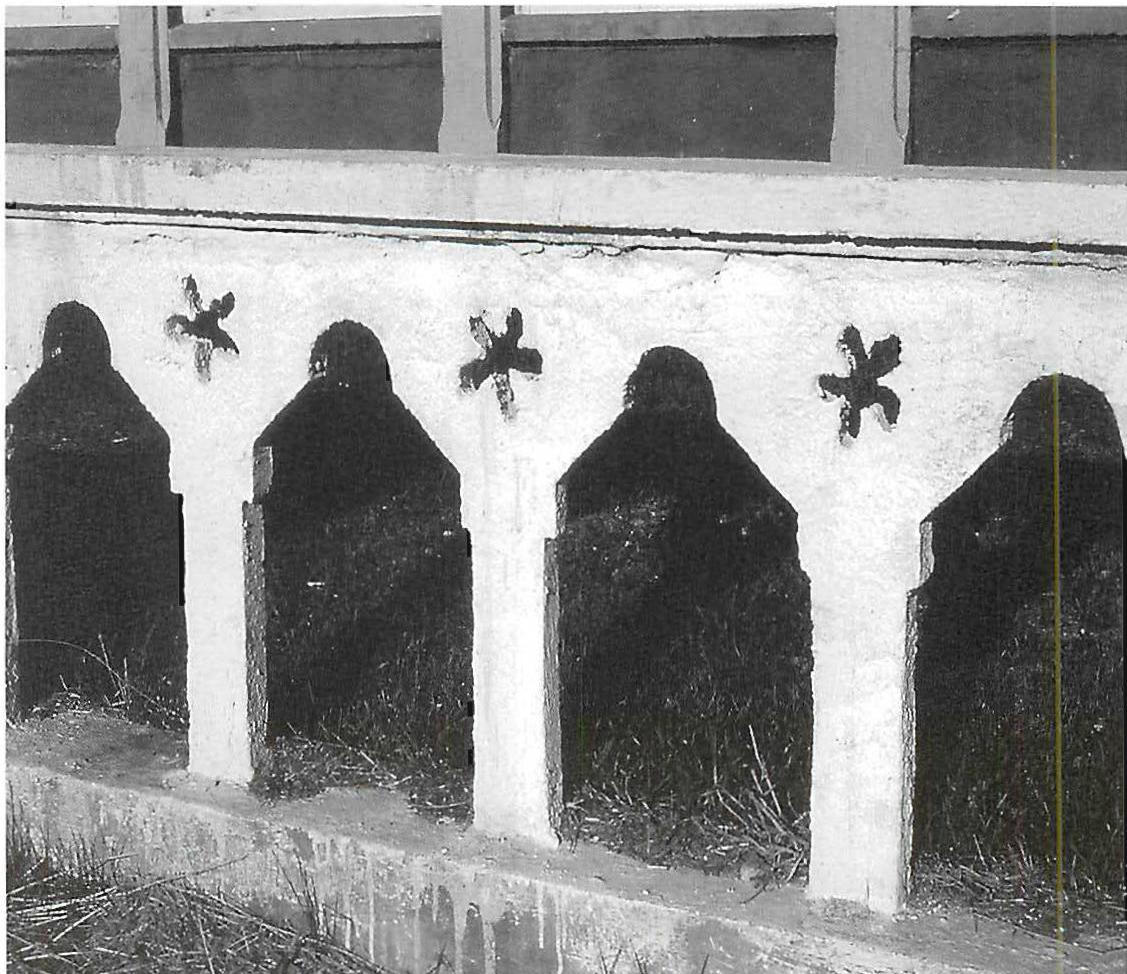

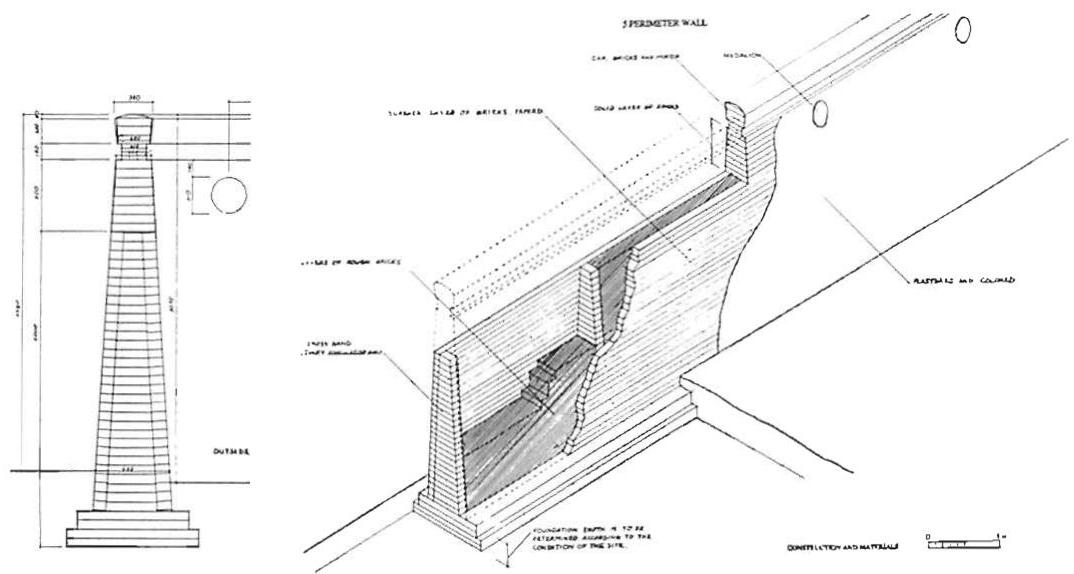

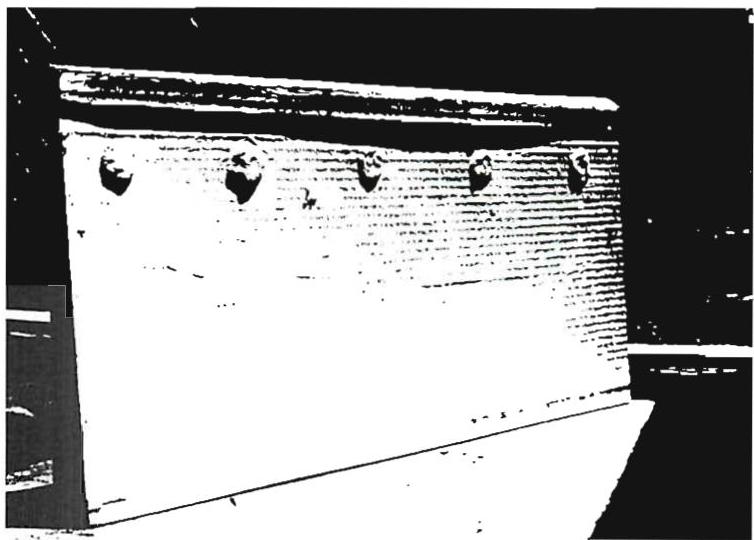

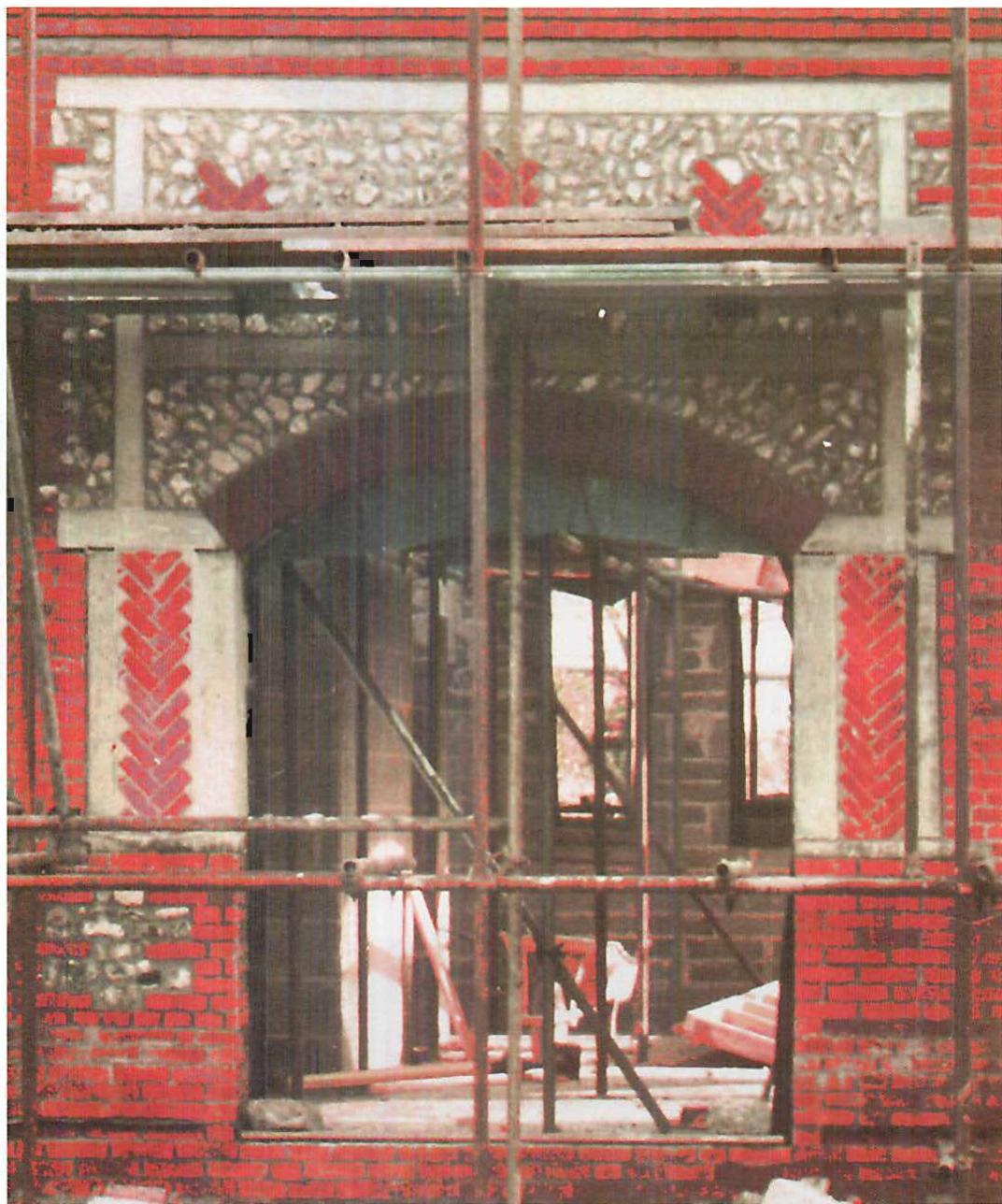

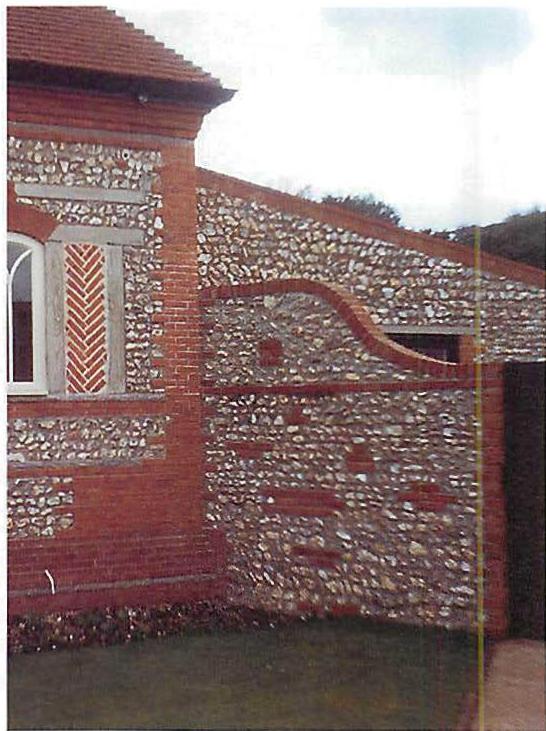

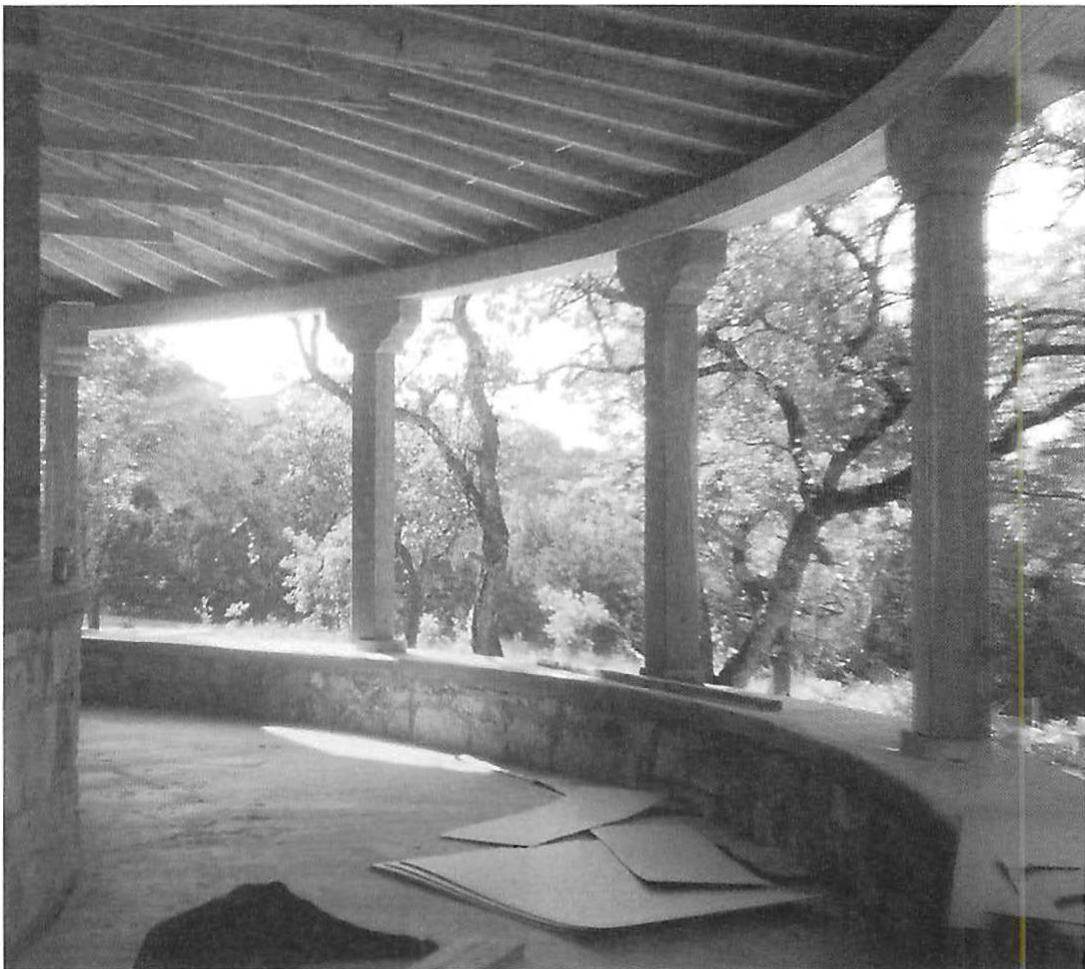

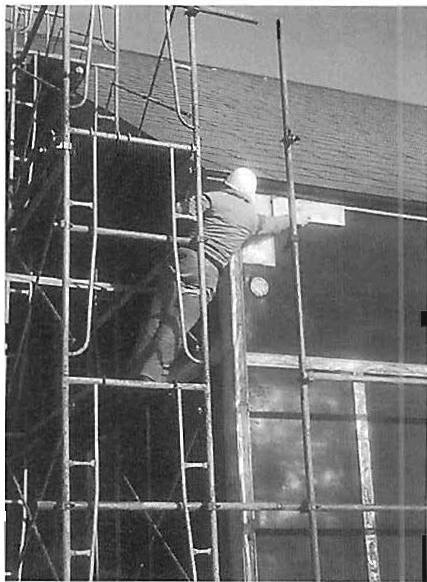

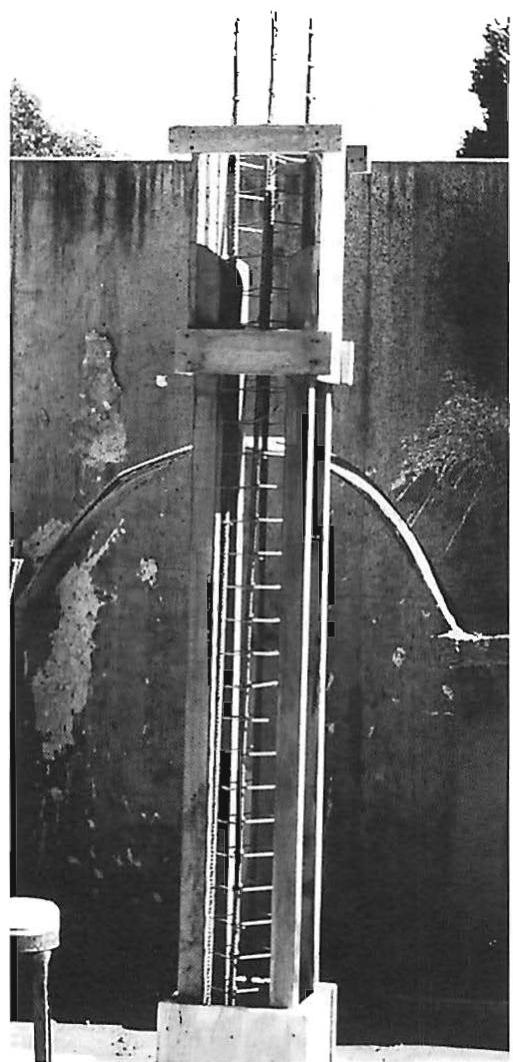

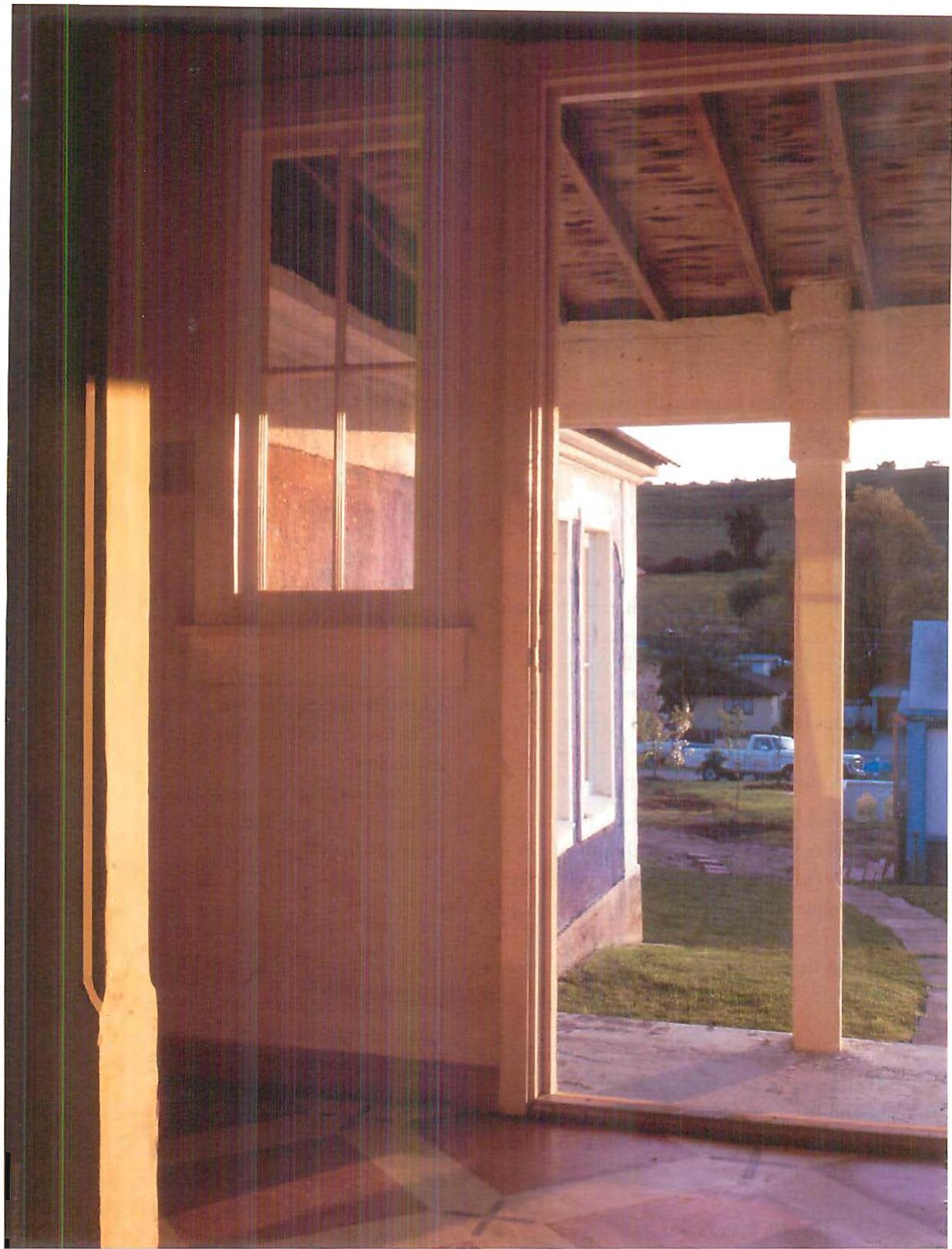

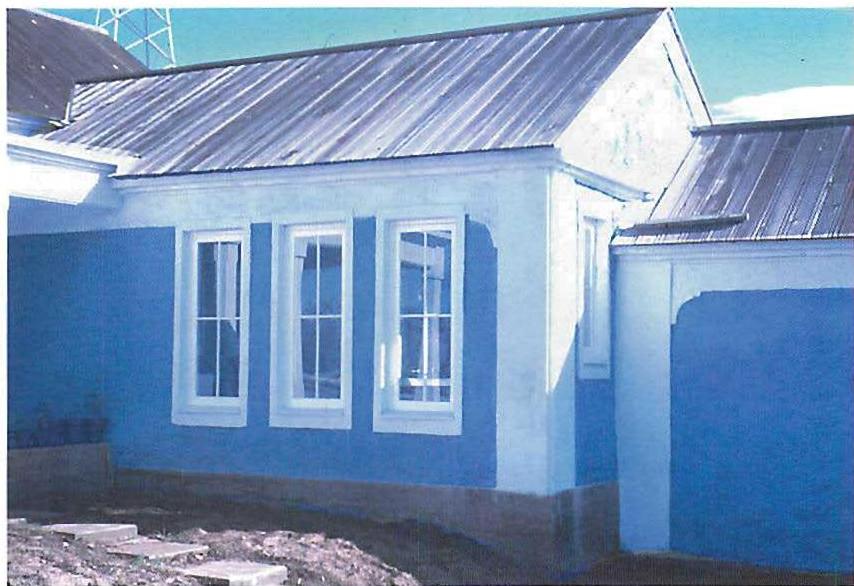

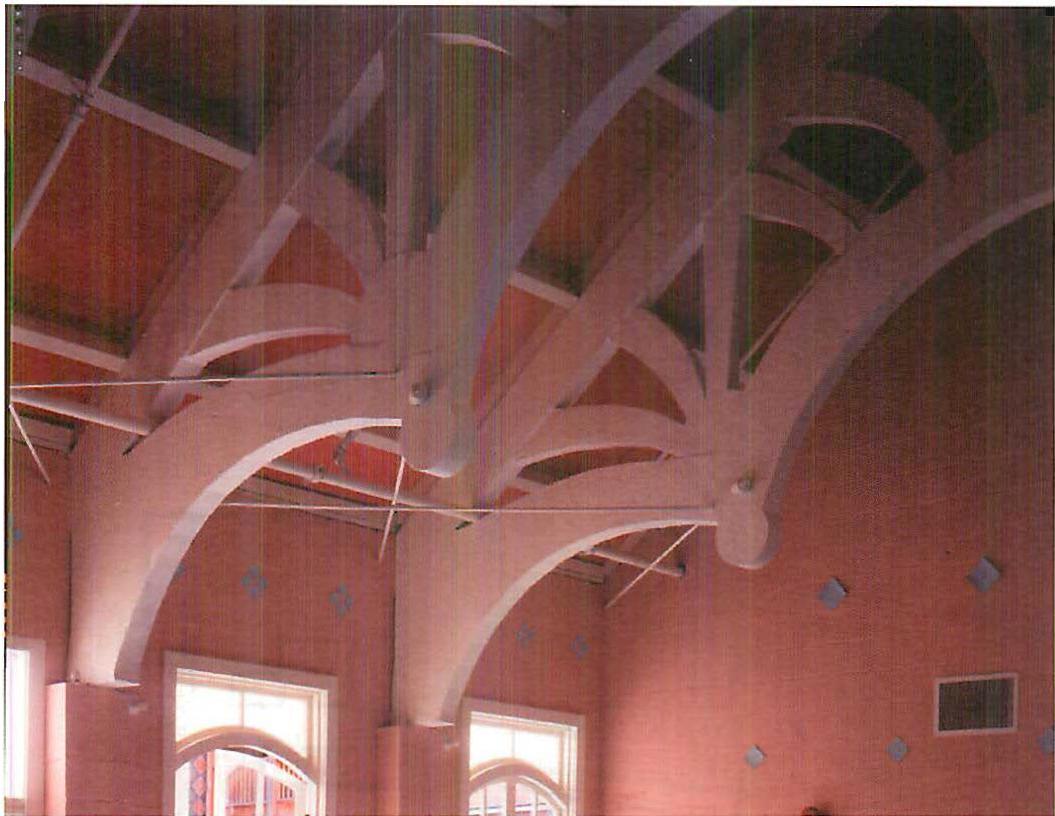

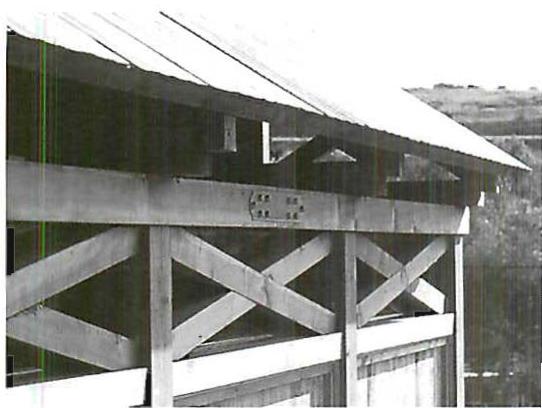

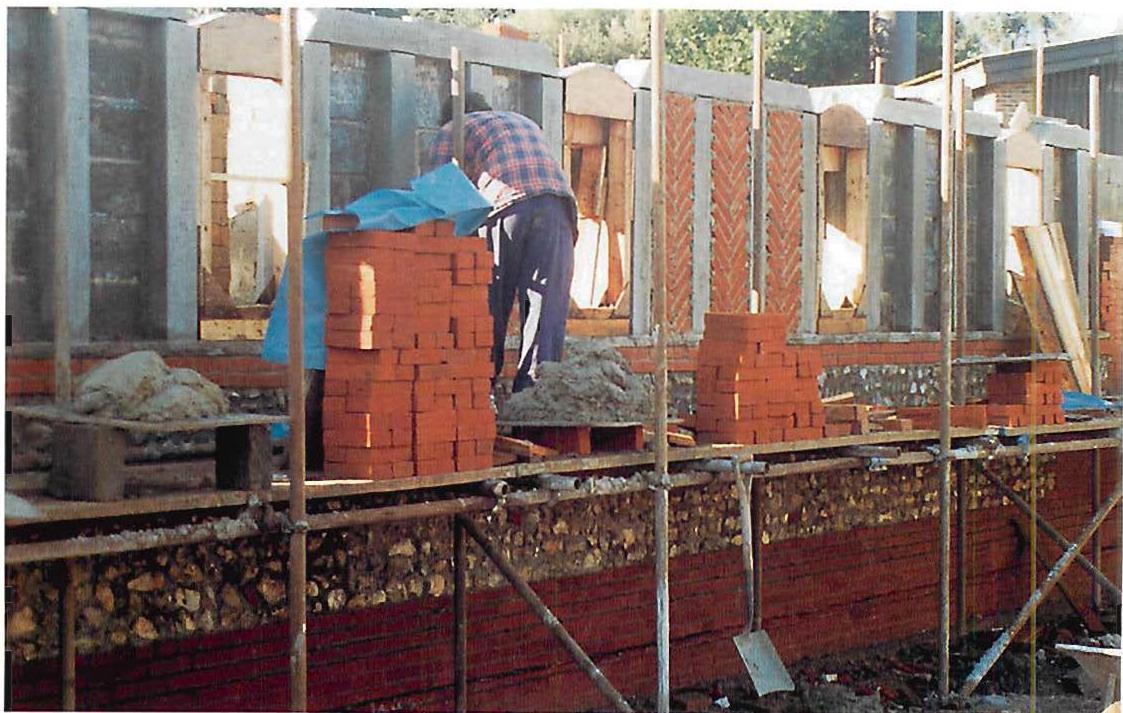

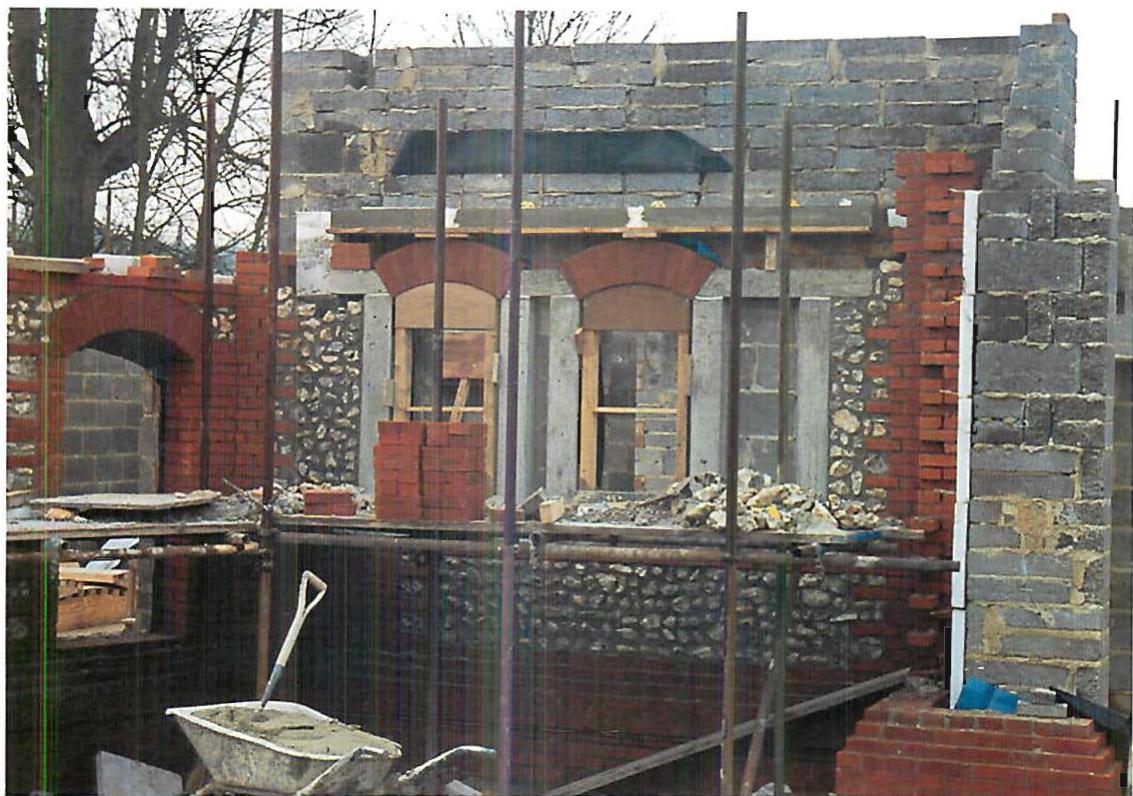

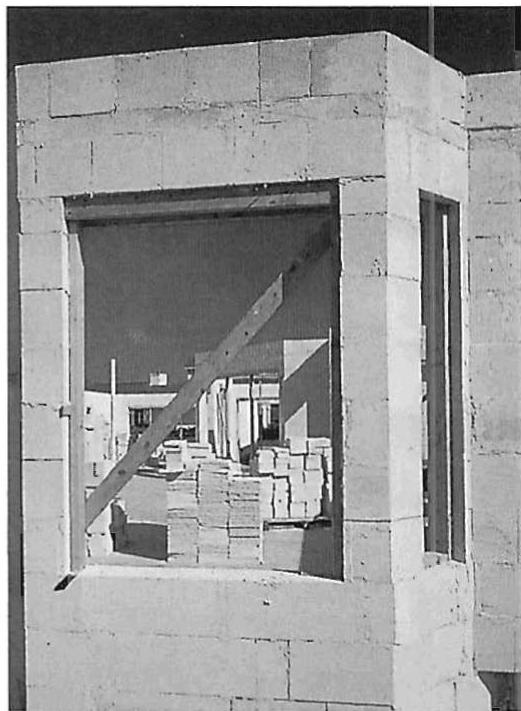

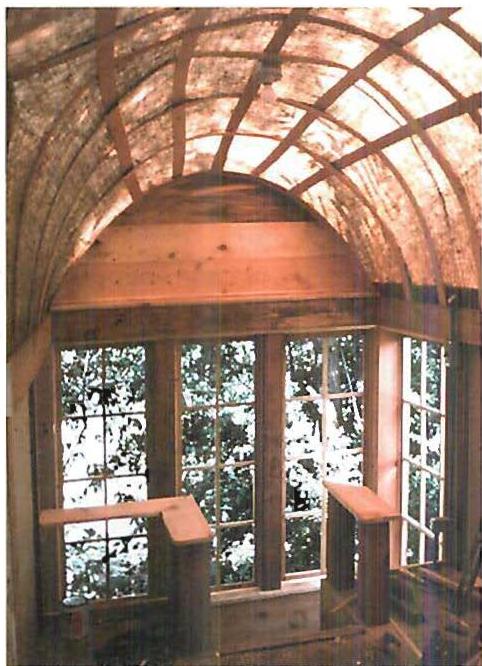

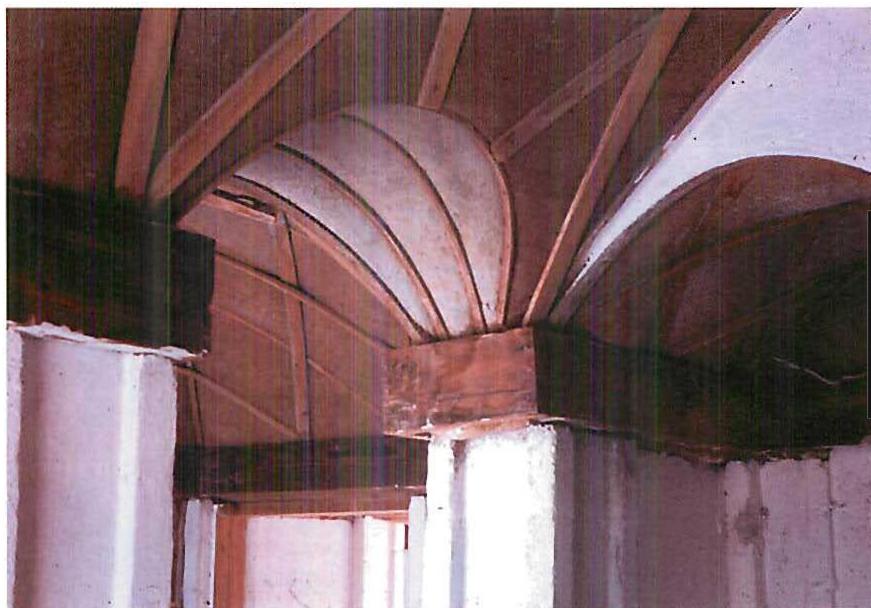

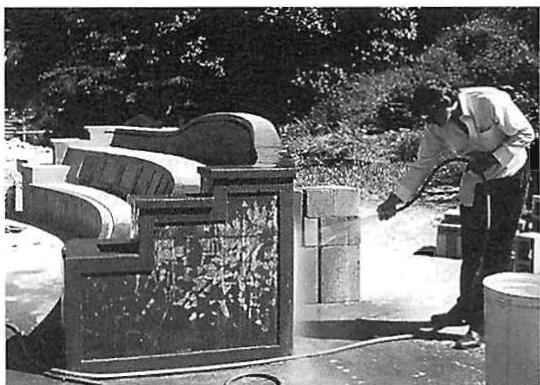

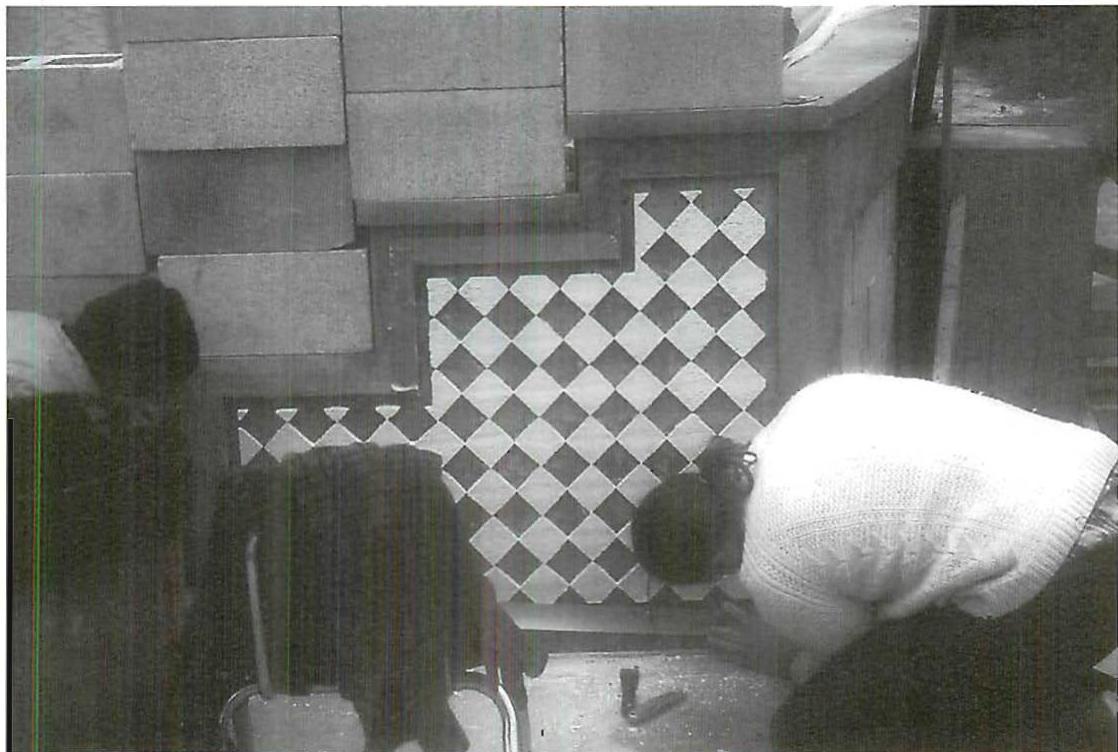

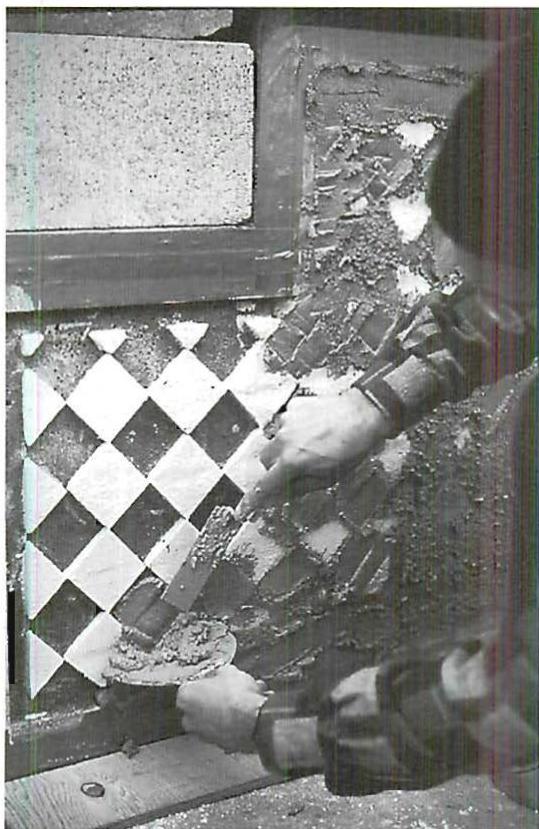

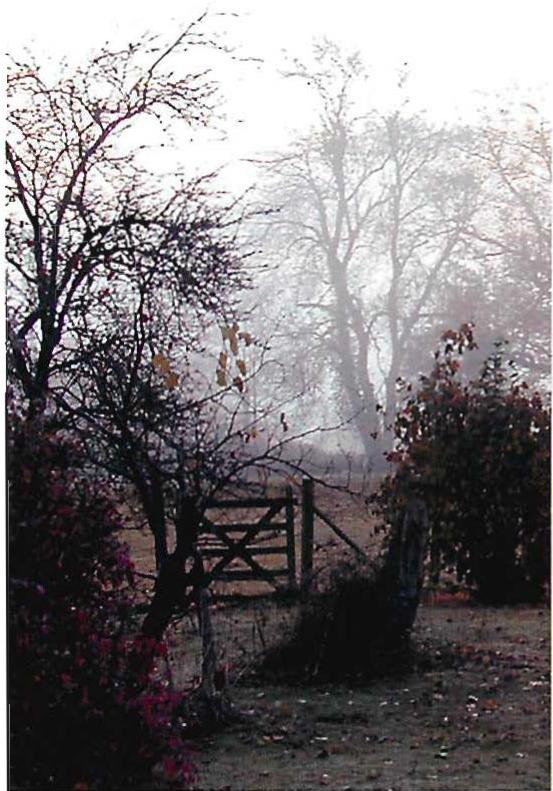

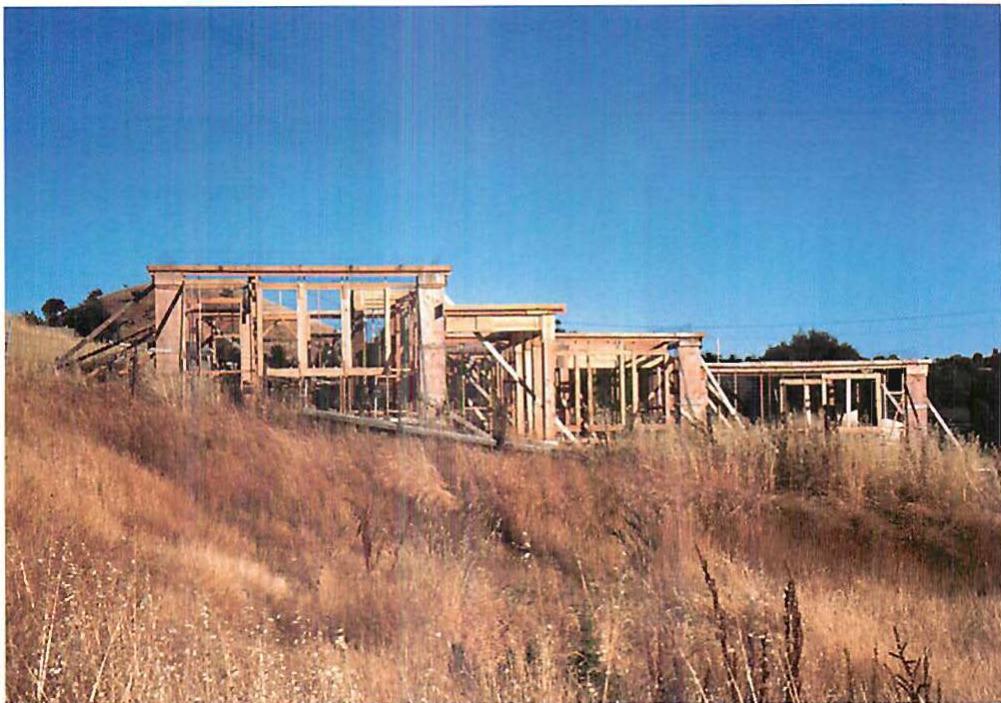

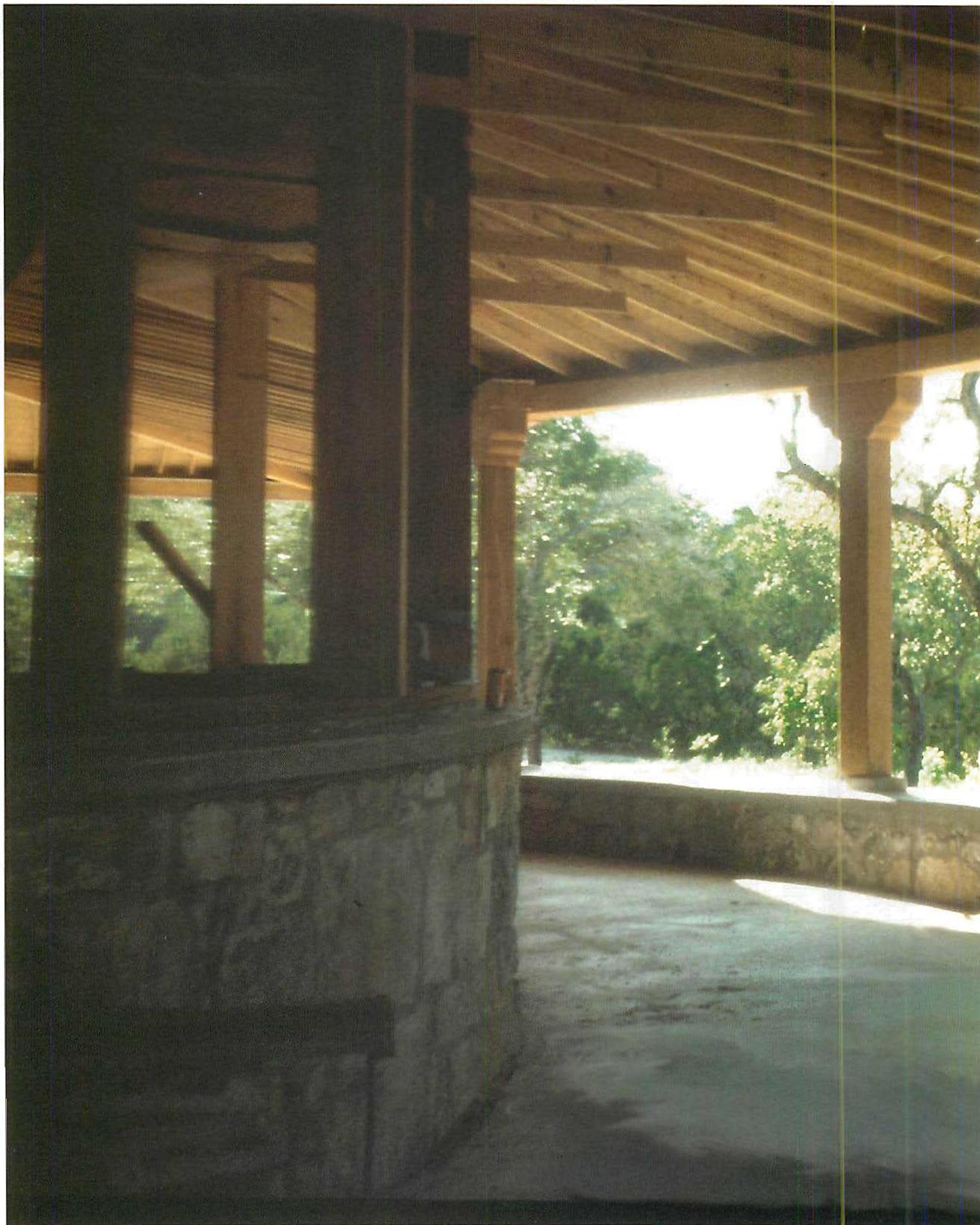

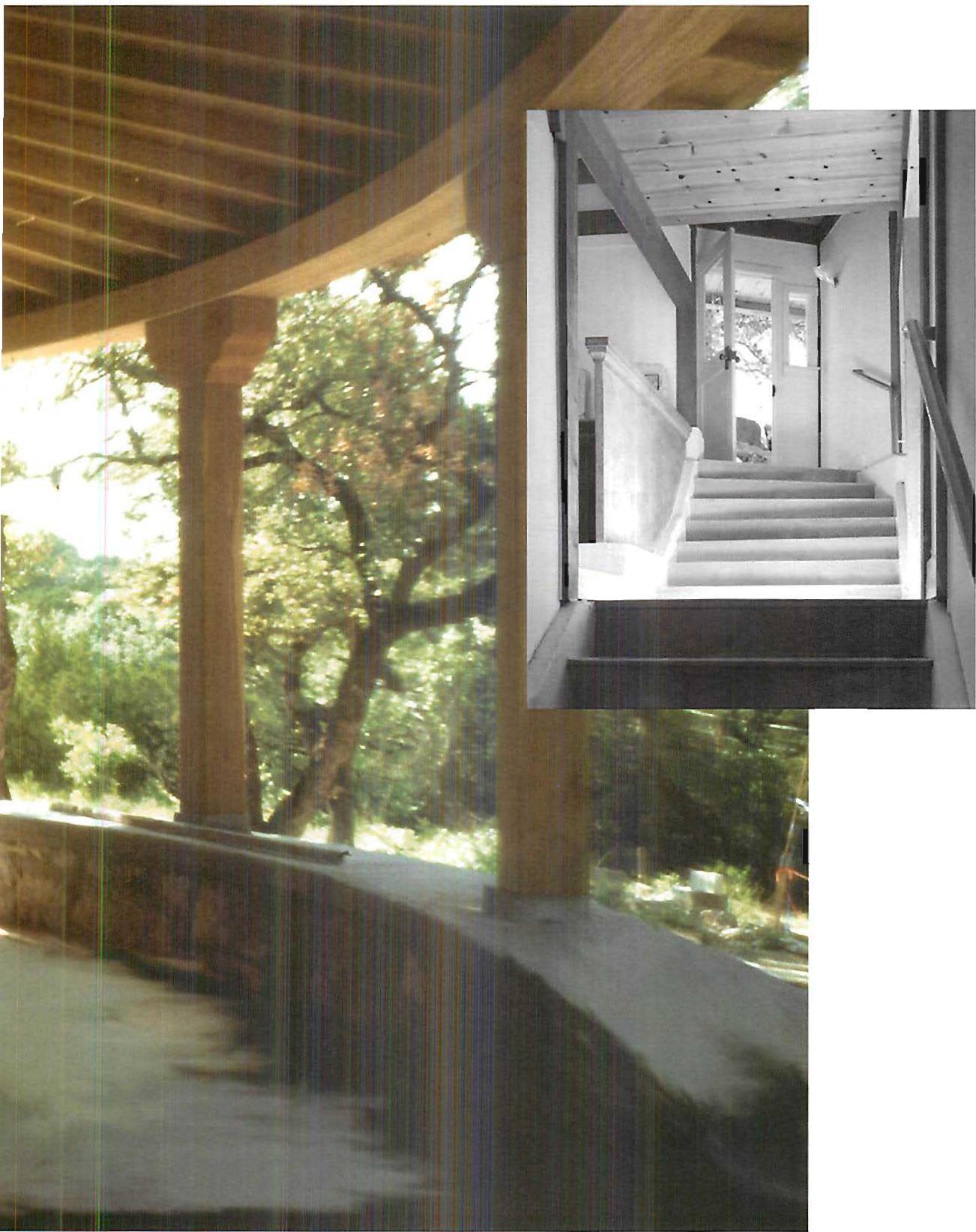

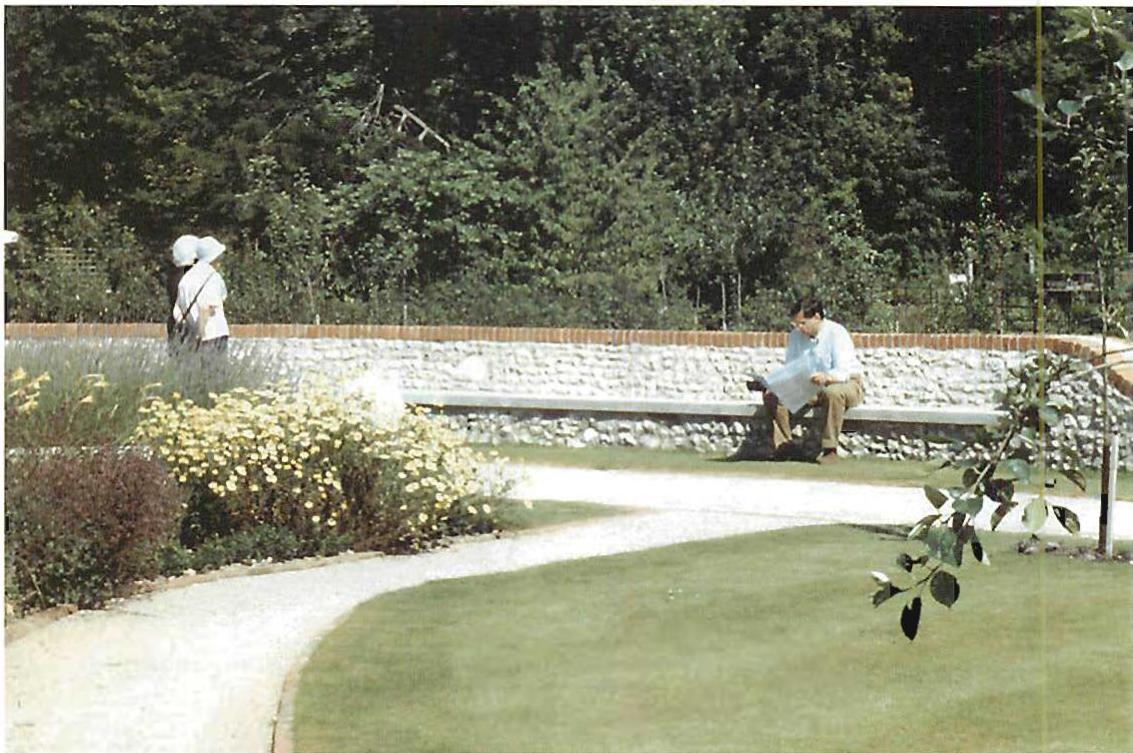

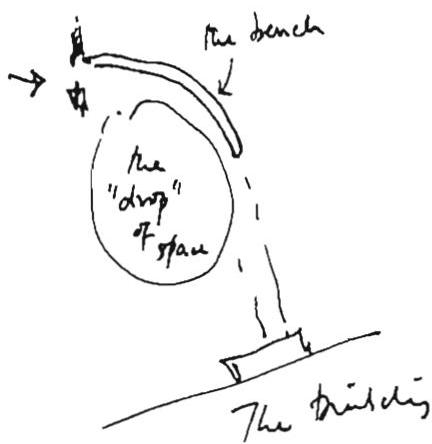

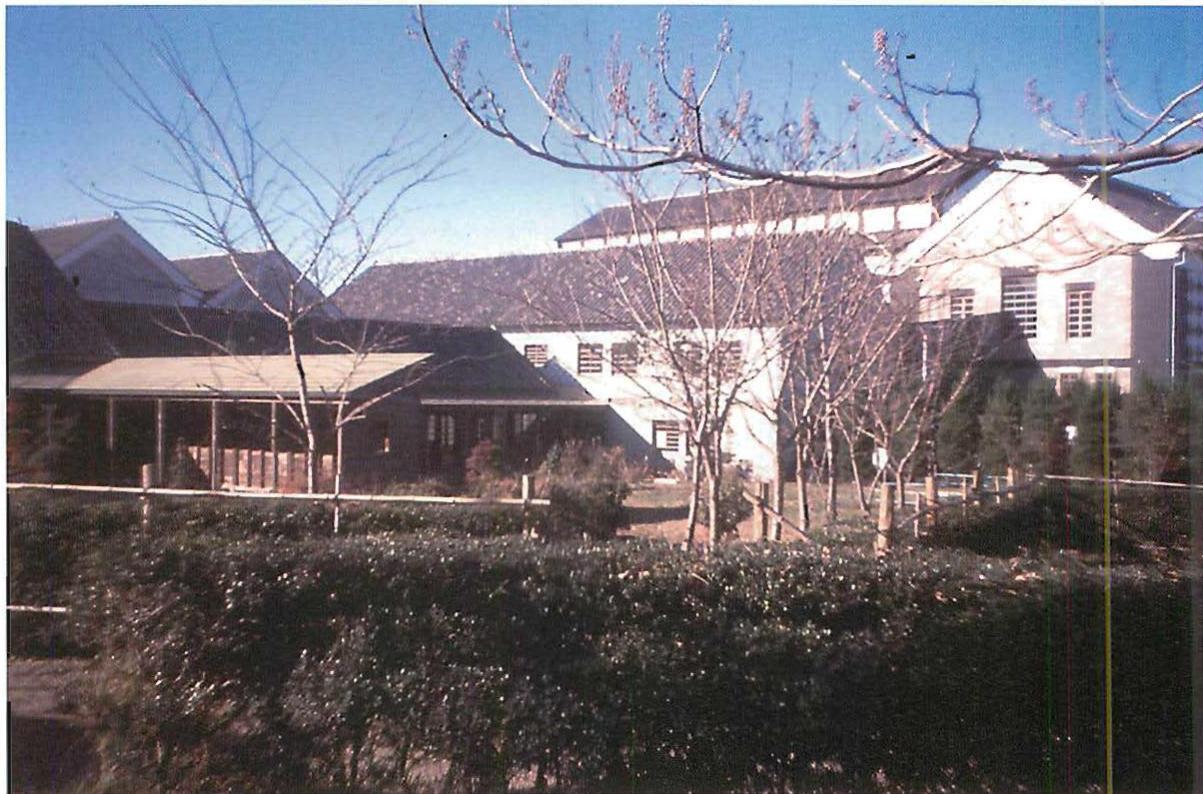

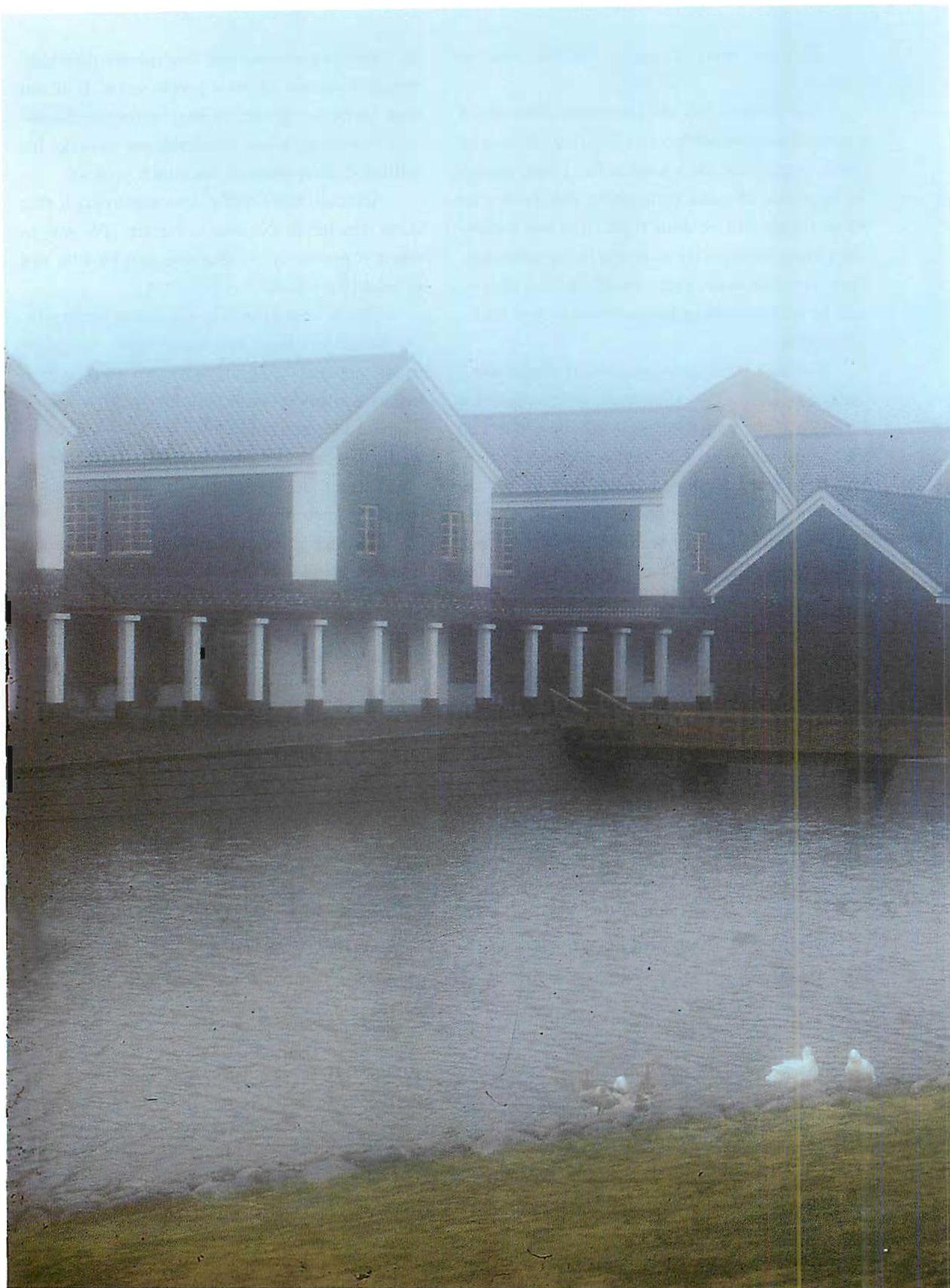

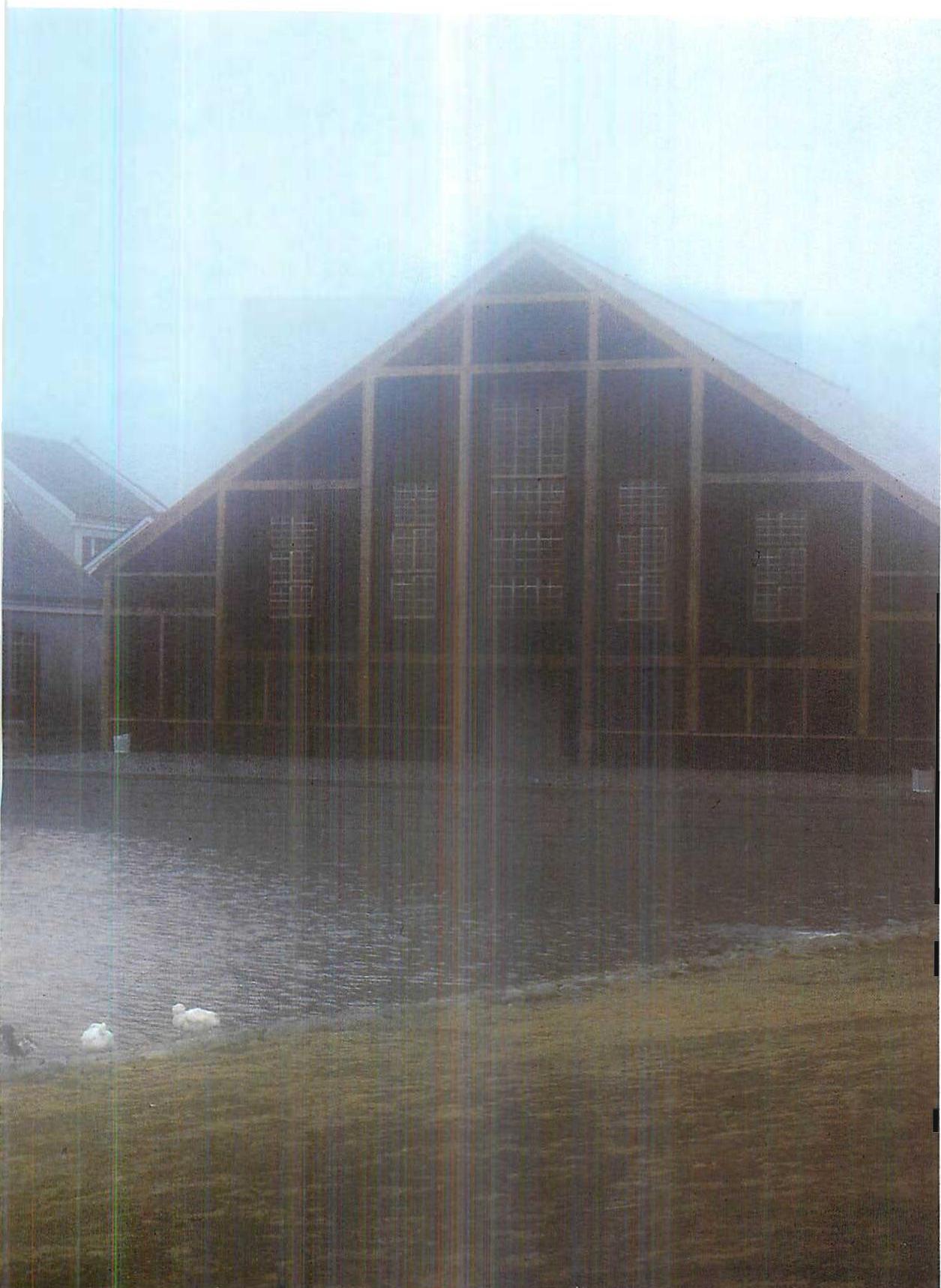

CONSTRUCTION OF A VISITORS CENTER IN SOUTHERN ENGLAND

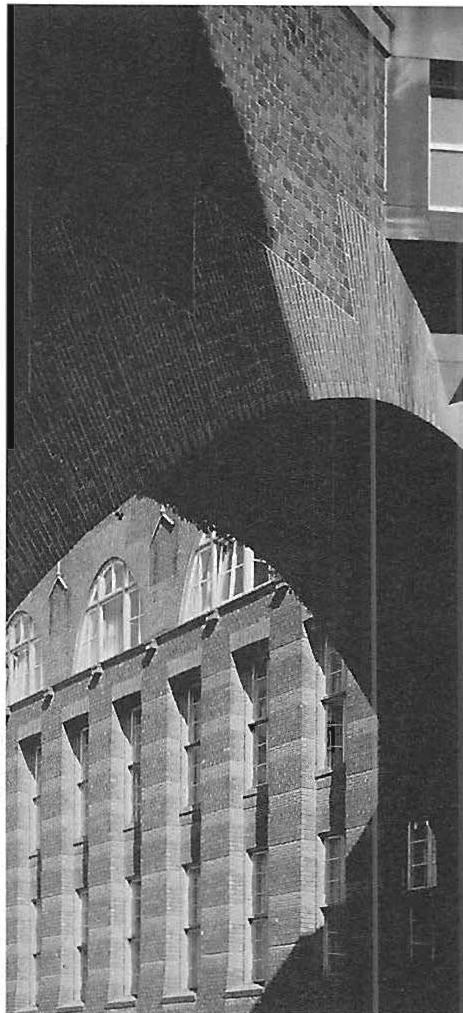

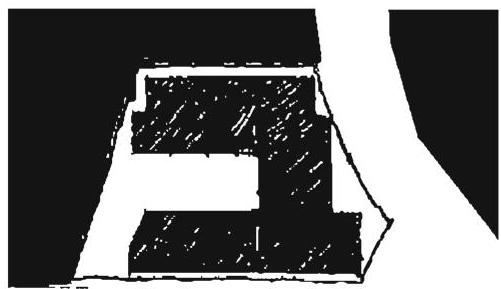

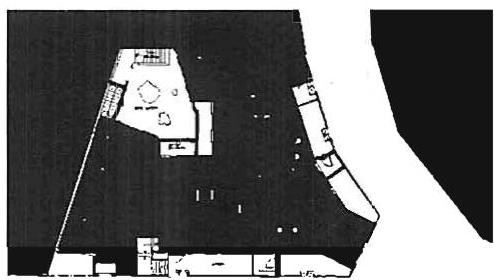

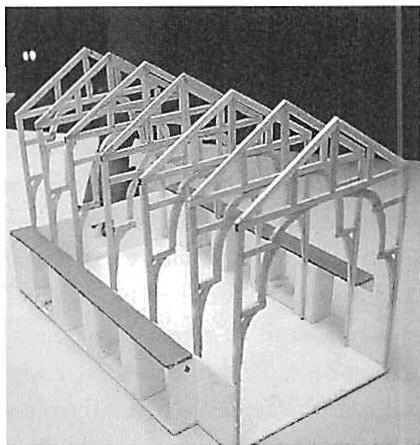

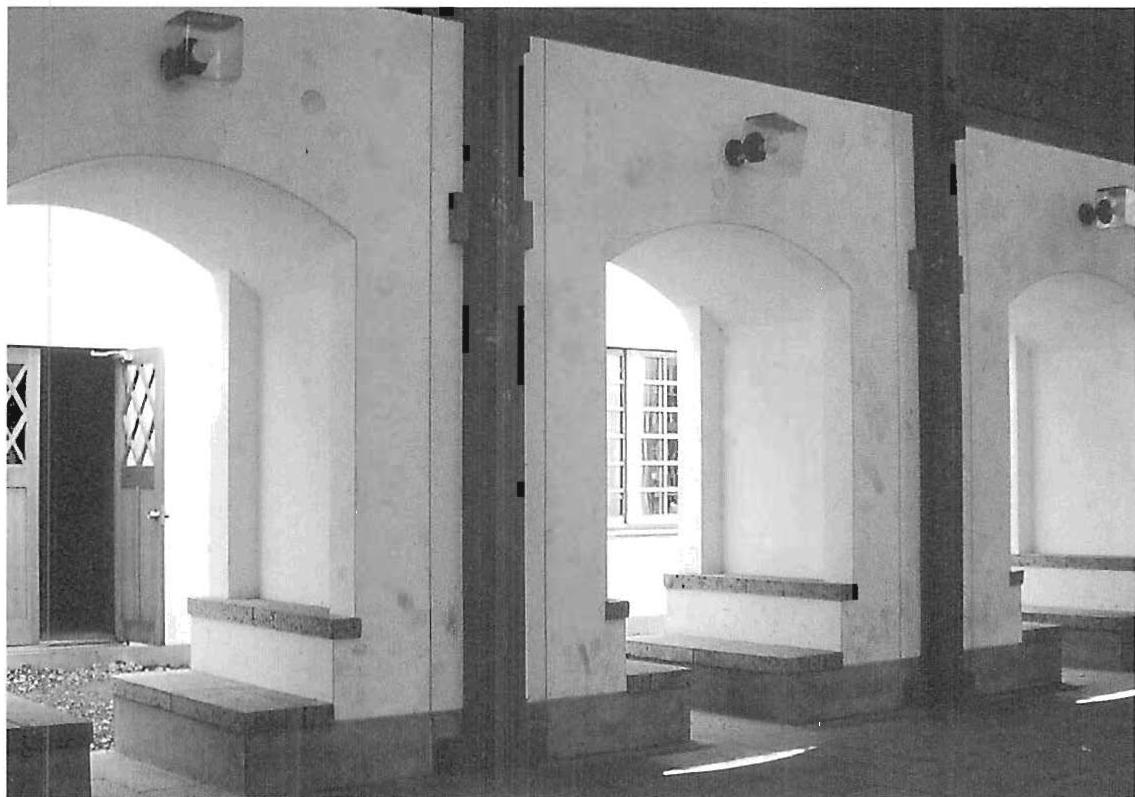

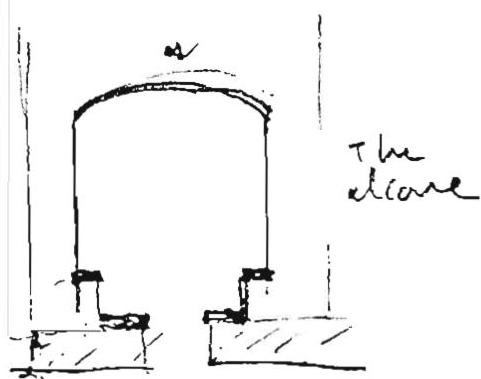

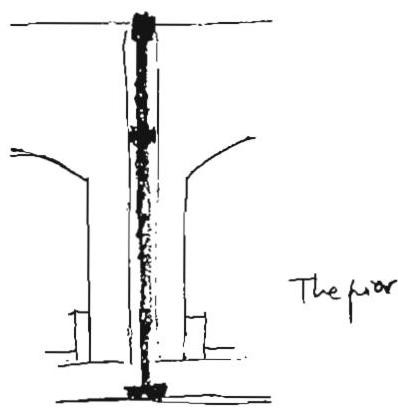

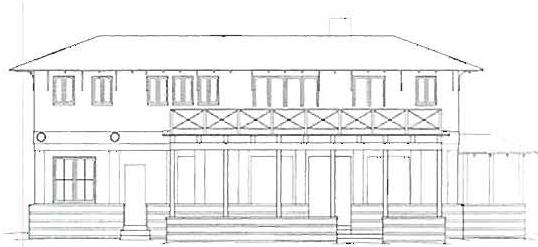

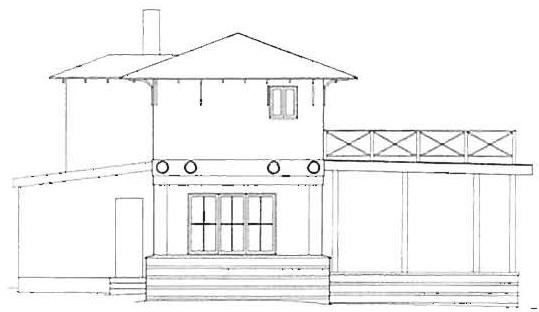

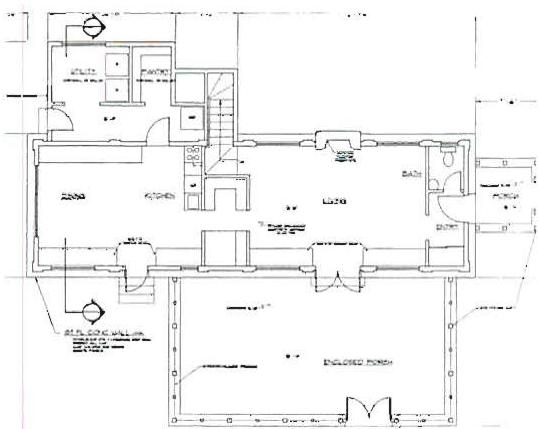

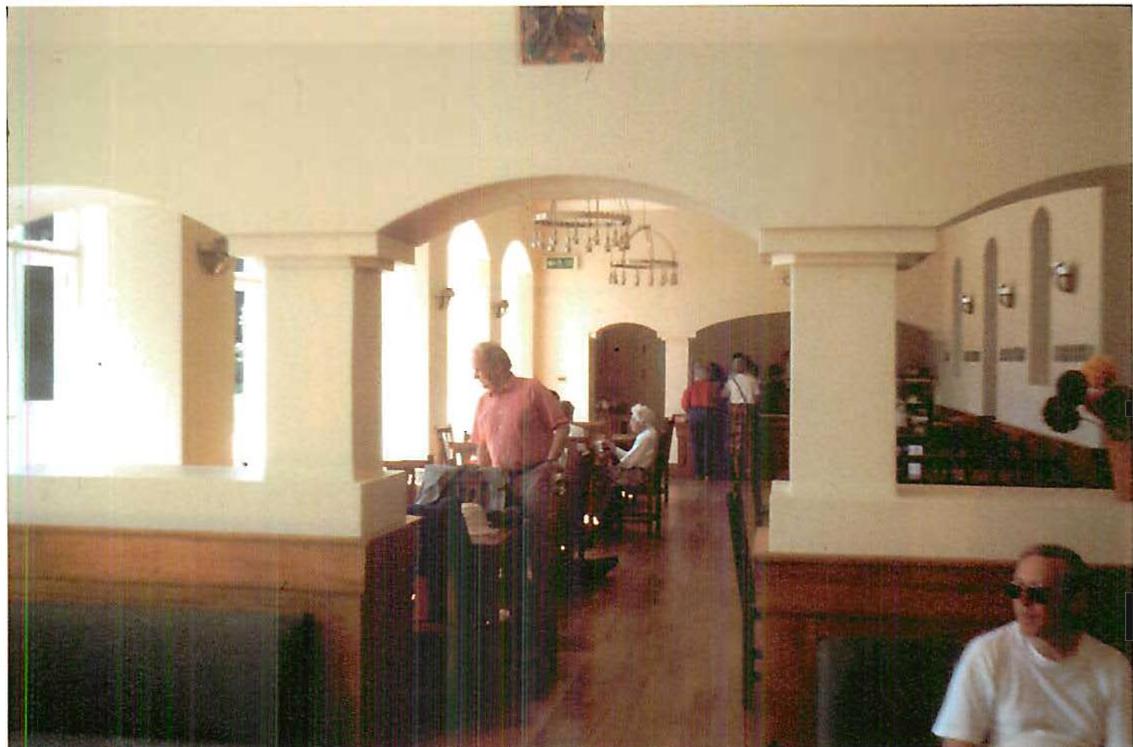

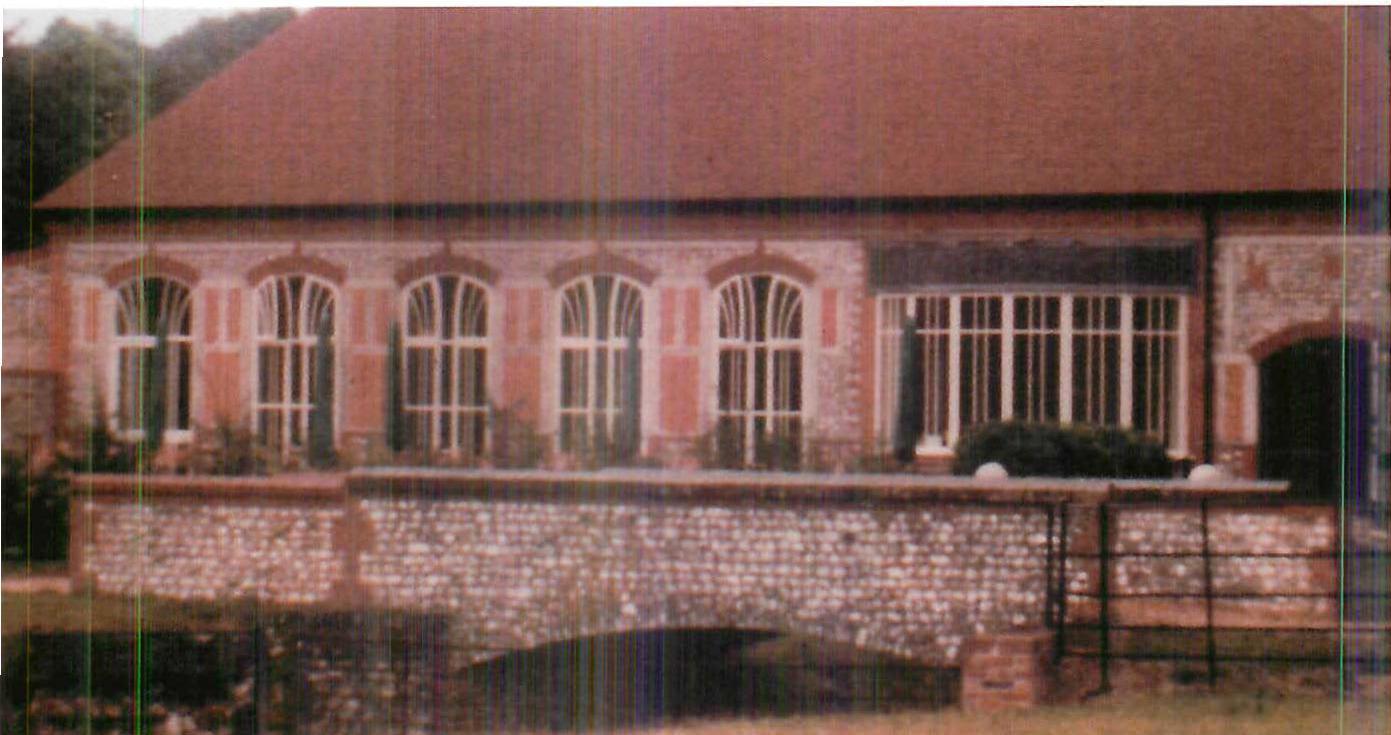

In another instance I built a visitor's center in England (these pages). Every step taken in the building, over a period of many months, defined some subtle condition which was shaped, perfected, and adapted by some further step of observation, measurement, mockup, discussion and construction. The process of designing and constructing that building is described at length in Book 4 (pages 118-29), with discussion of the contracting details in this book (pages 145-47 and 240-41).

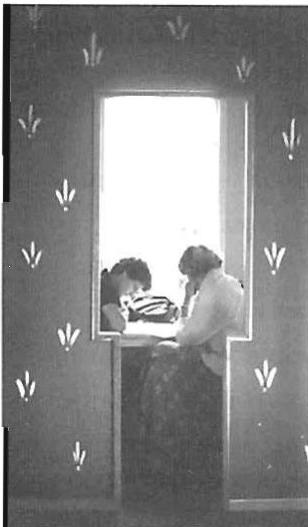

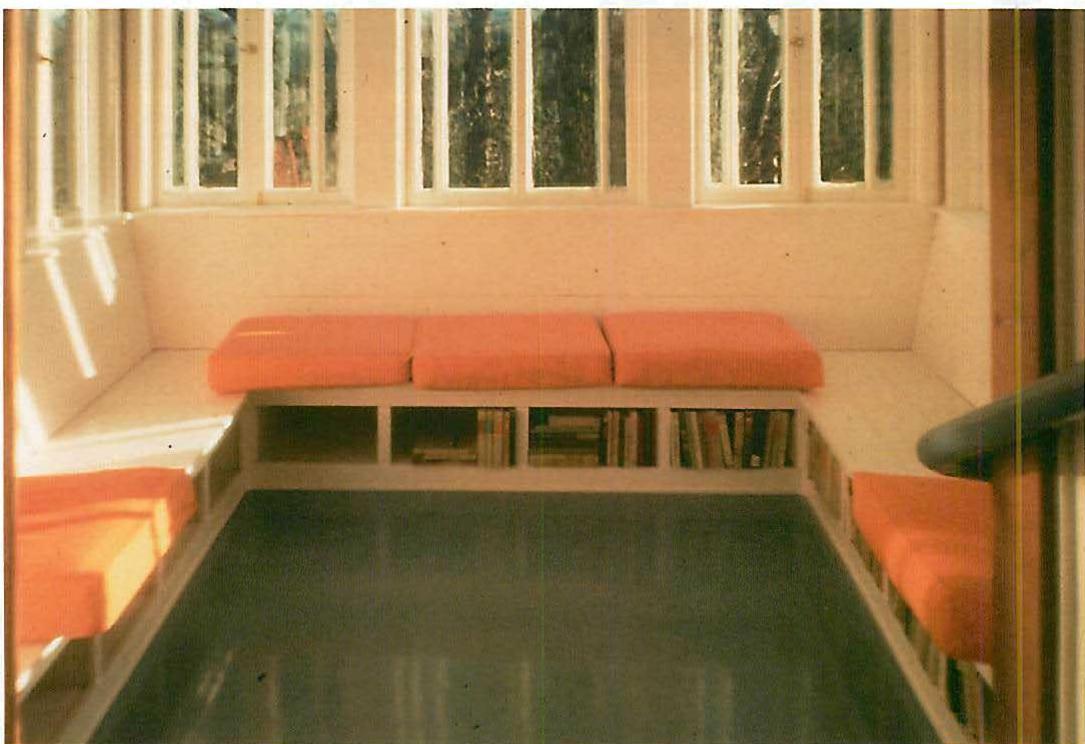

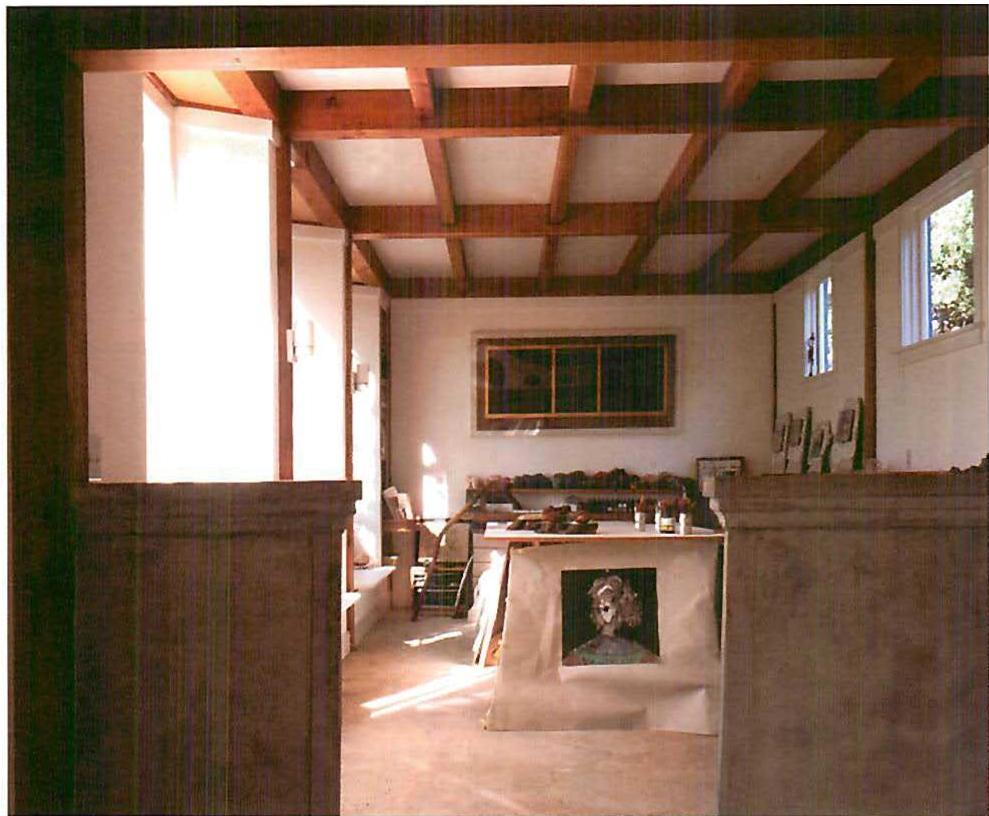

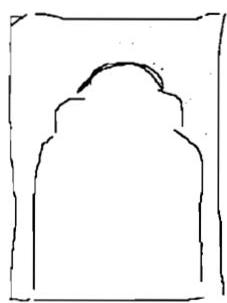

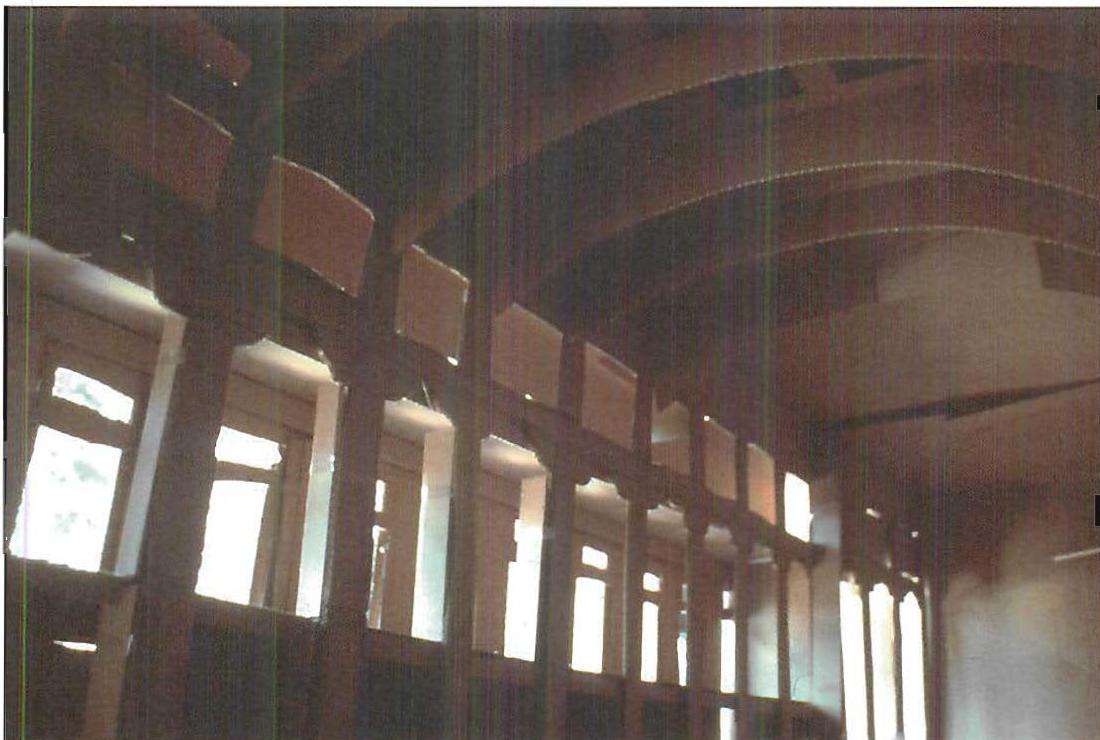

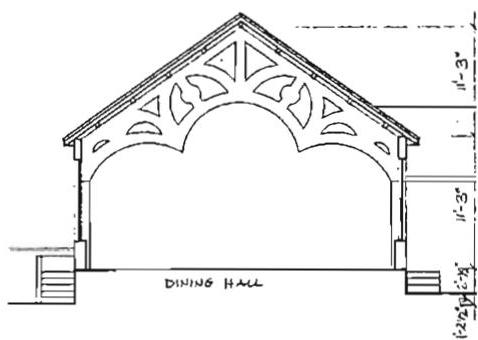

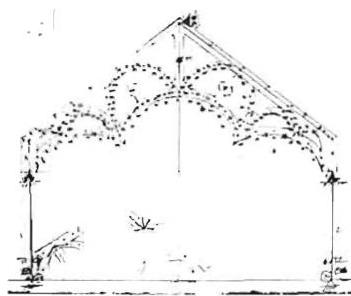

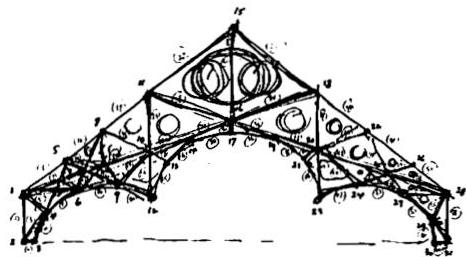

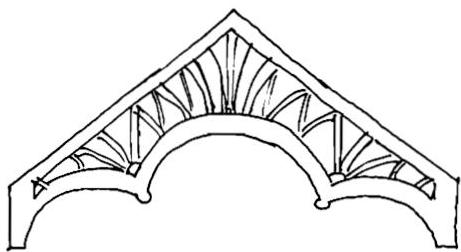

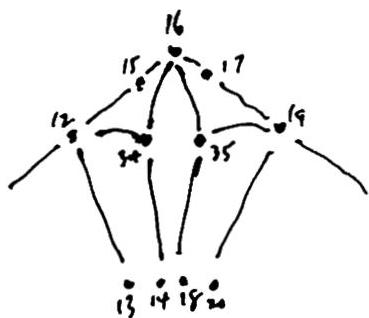

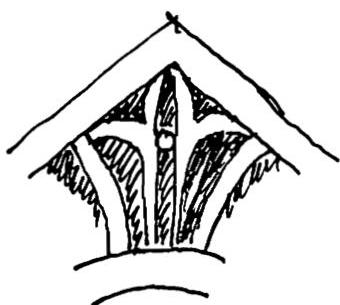

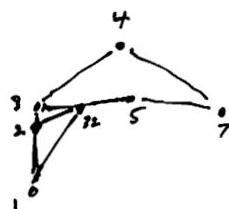

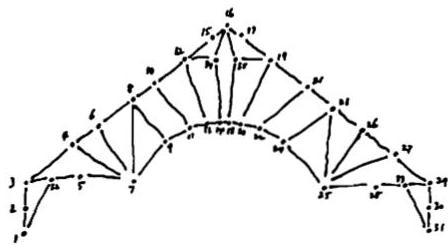

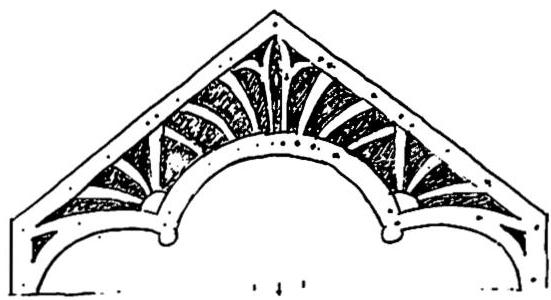

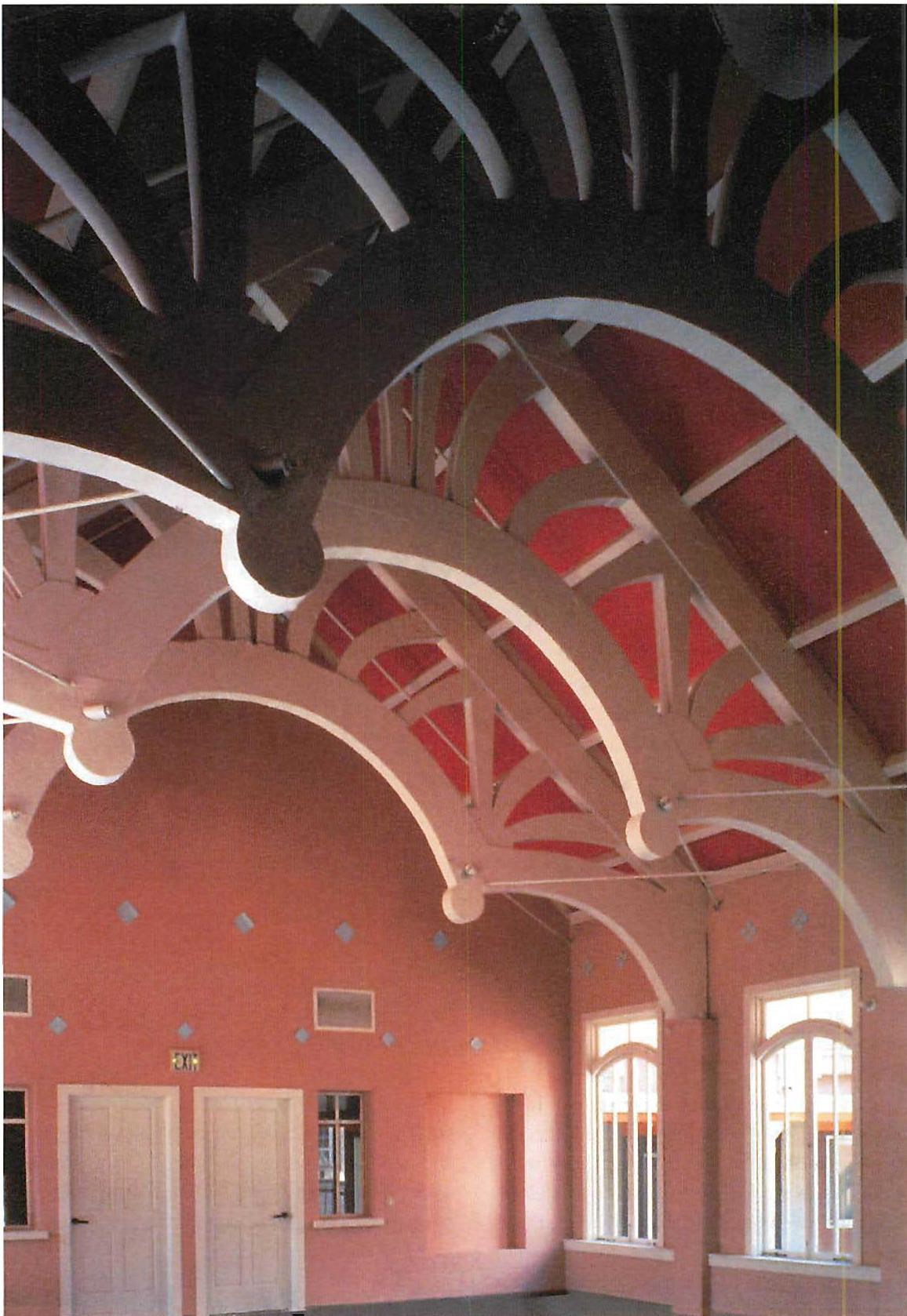

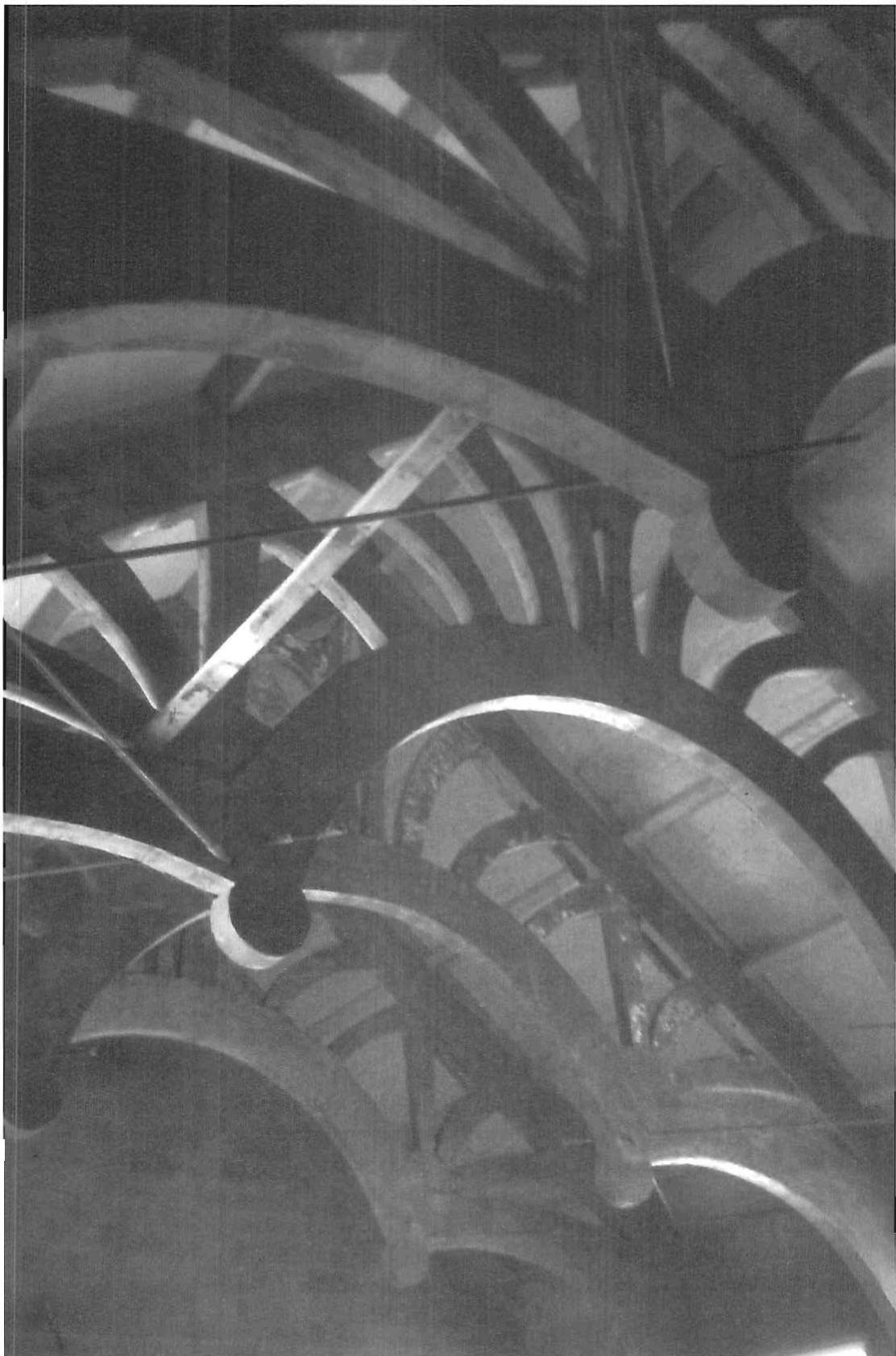

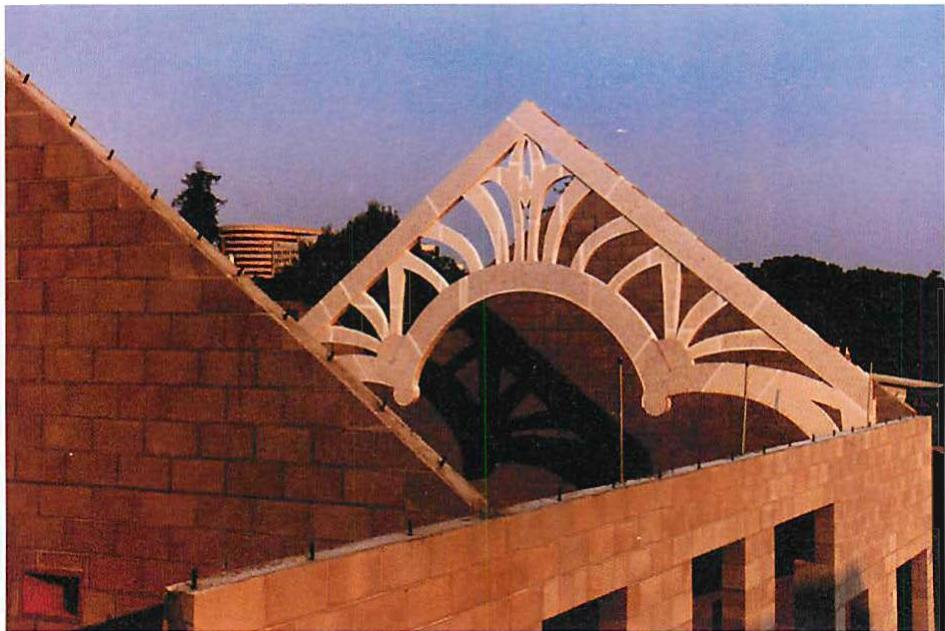

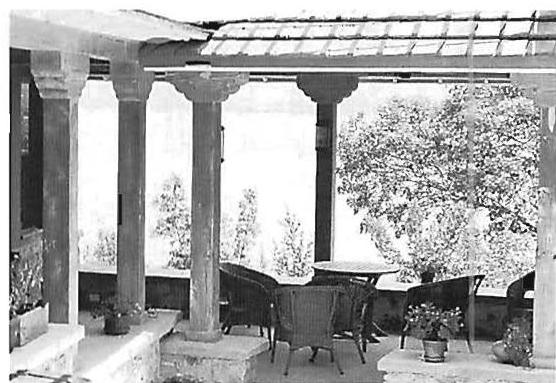

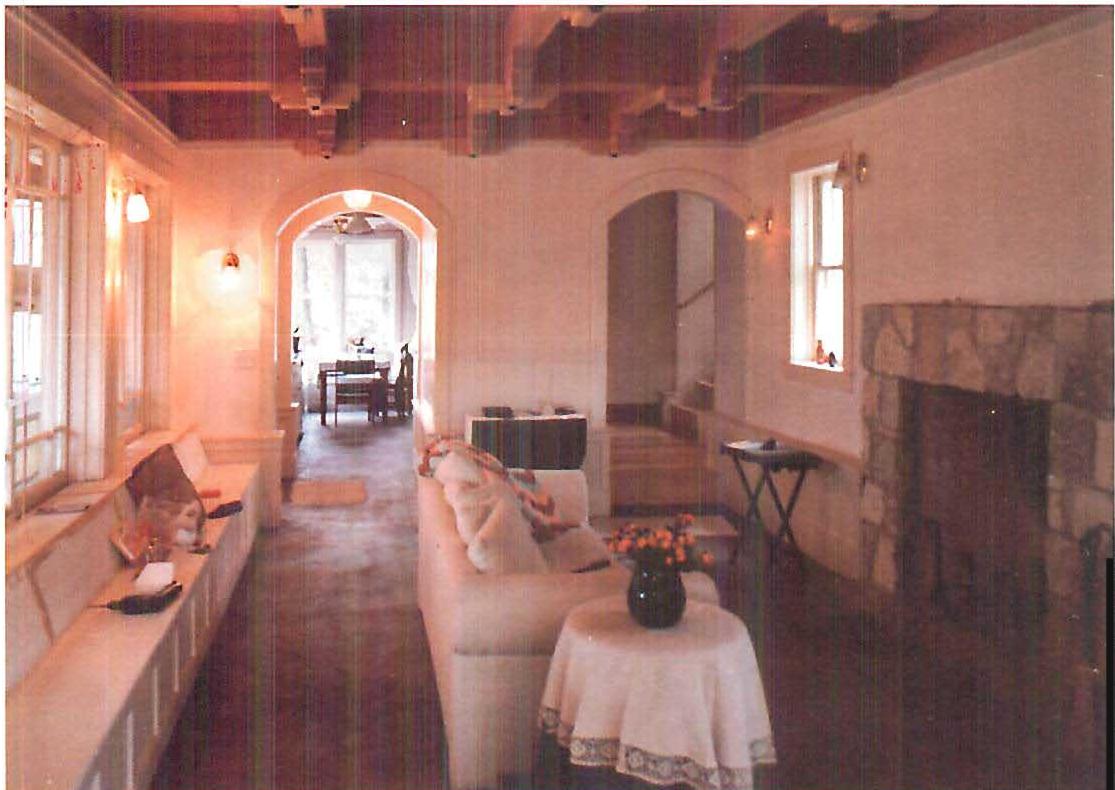

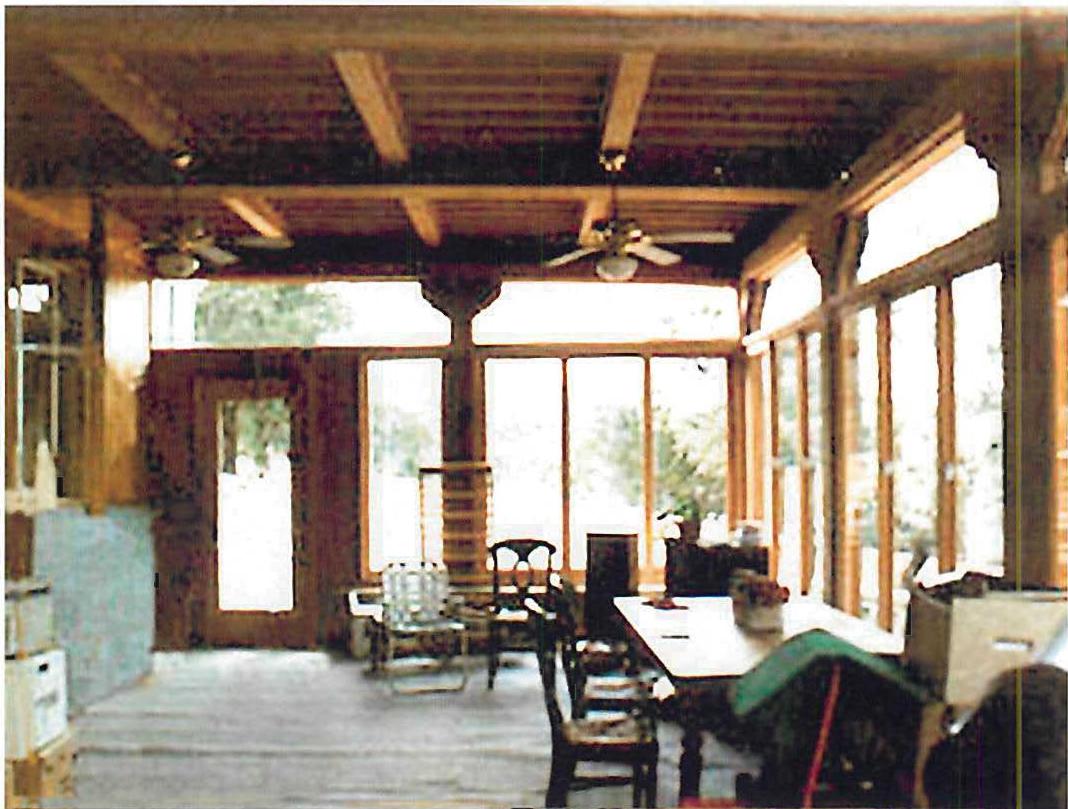

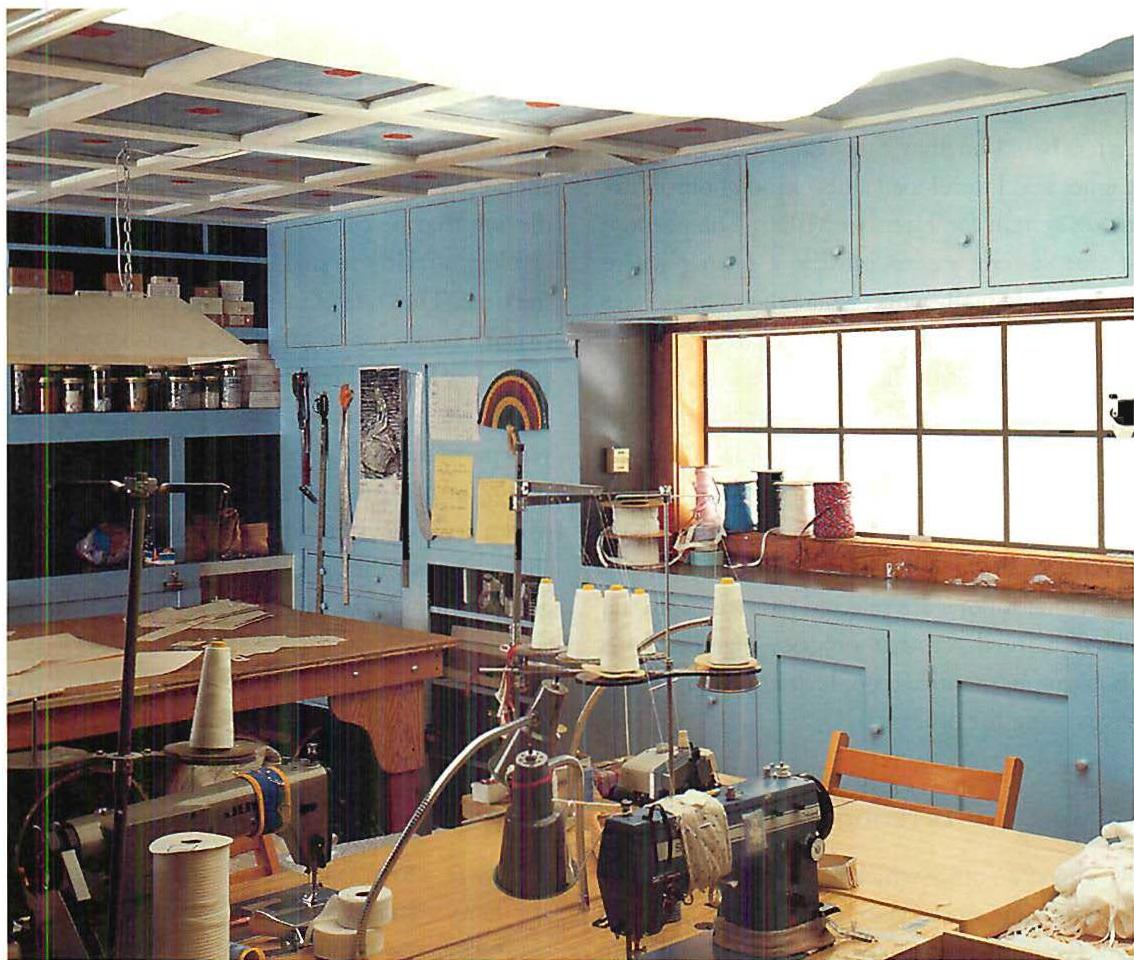

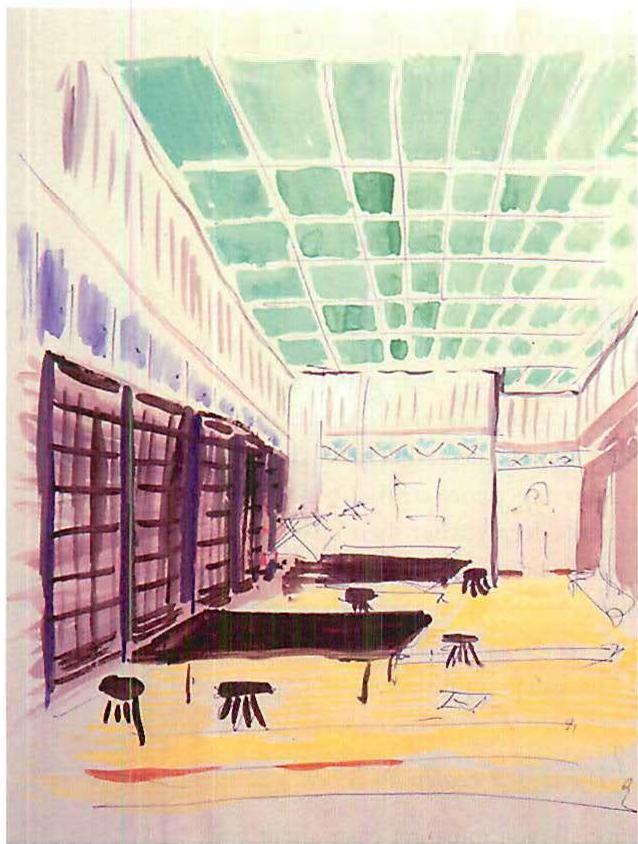

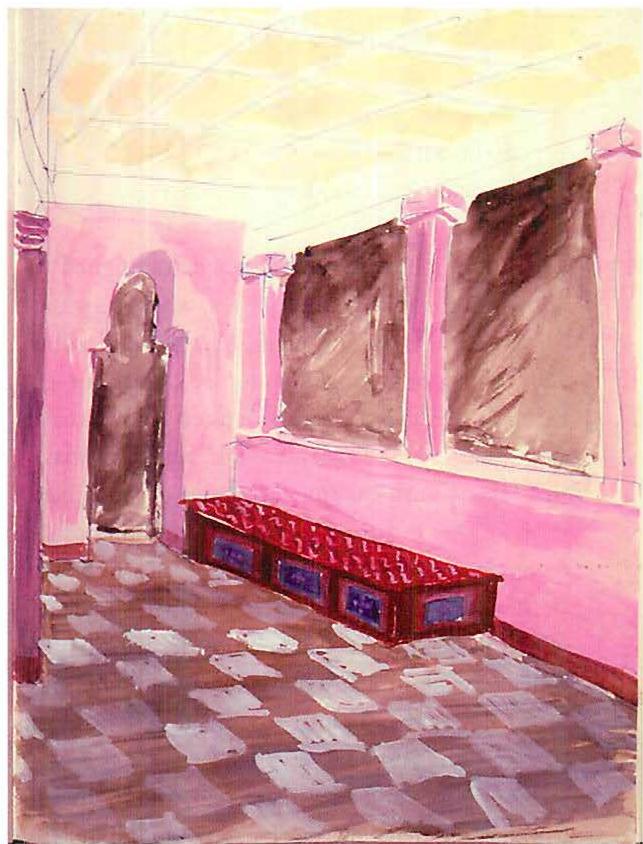

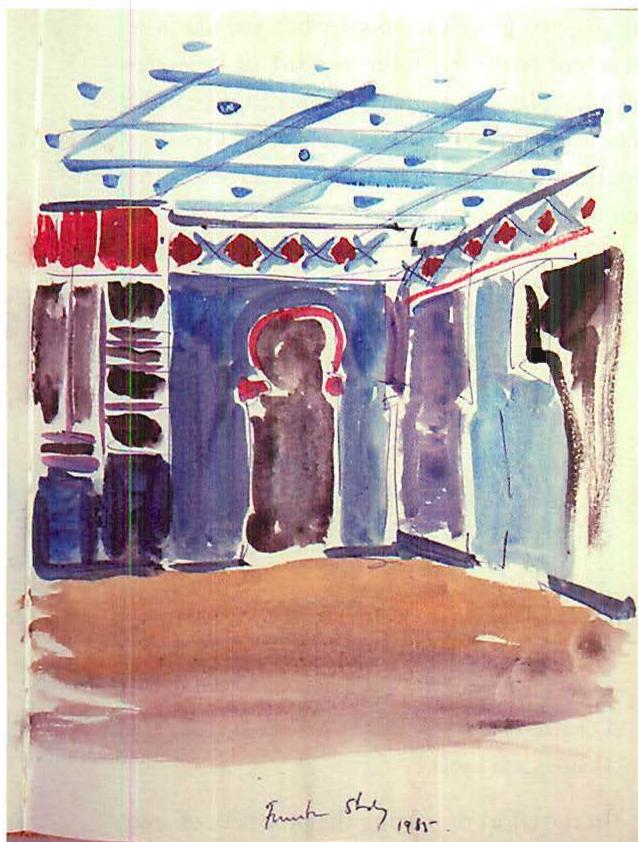

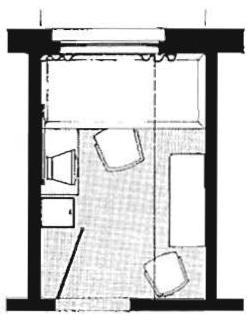

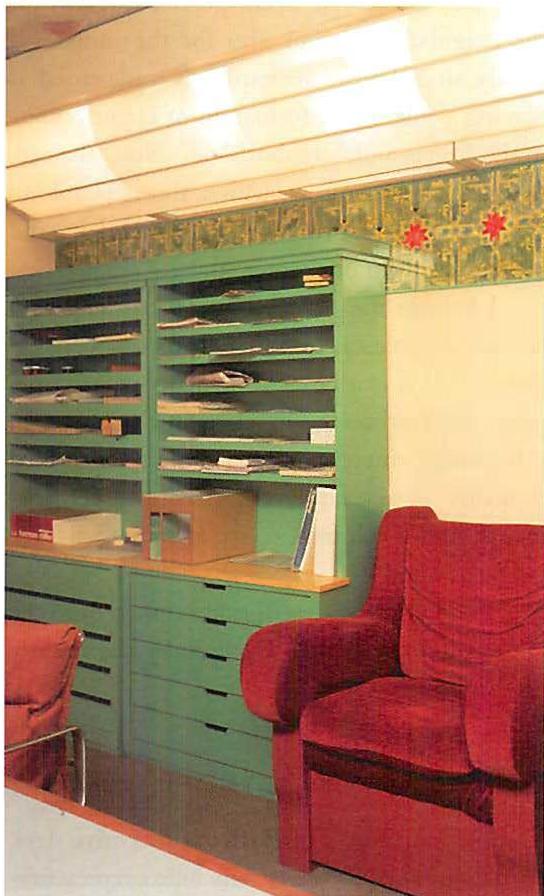

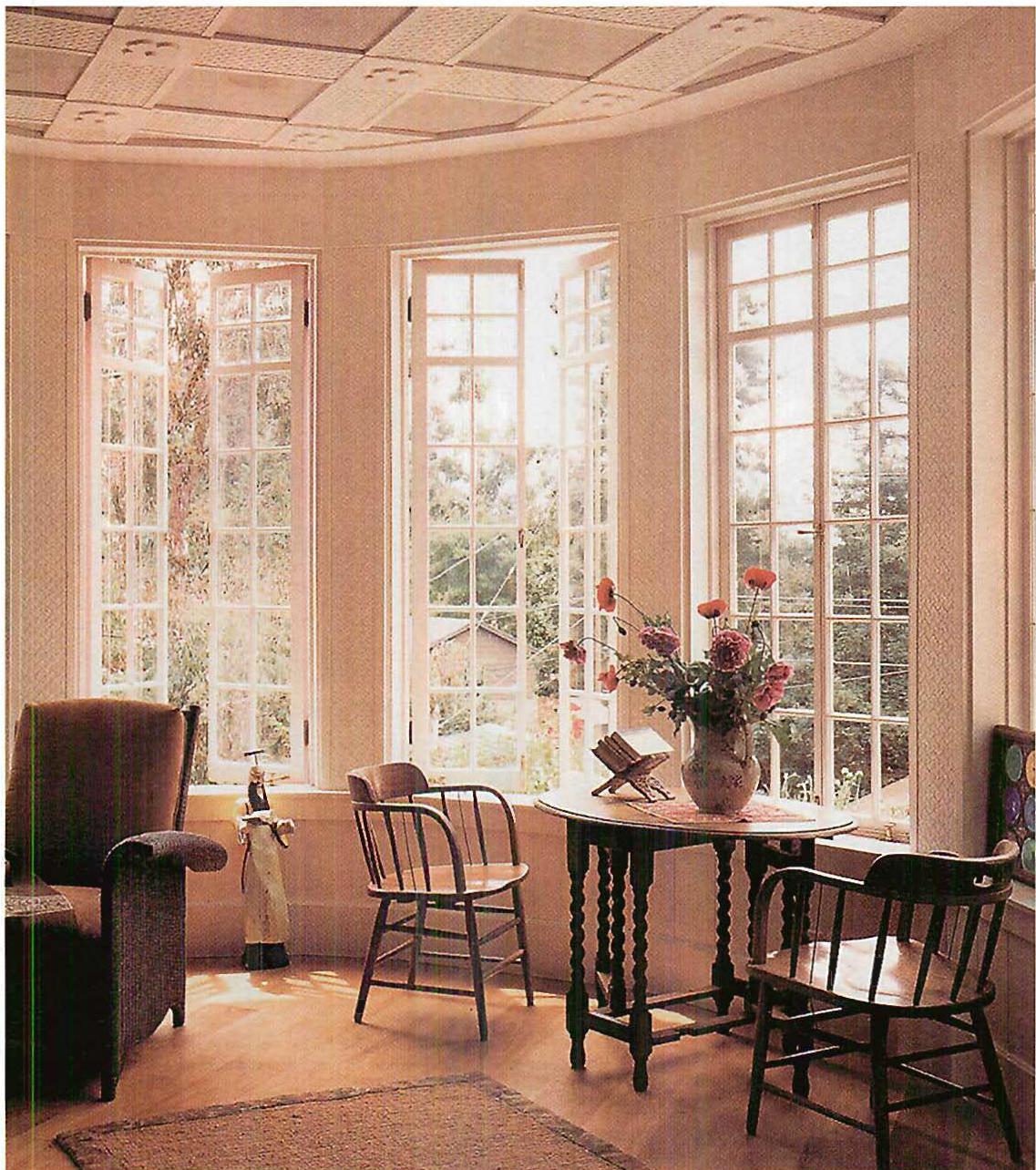

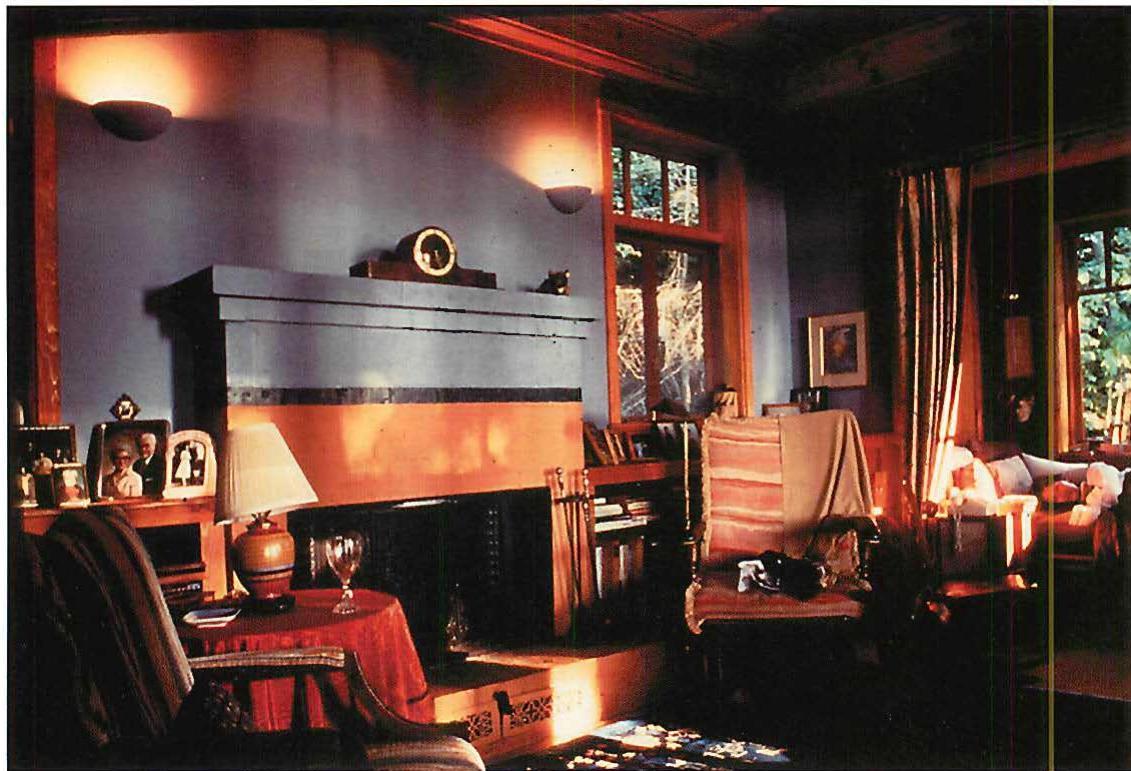

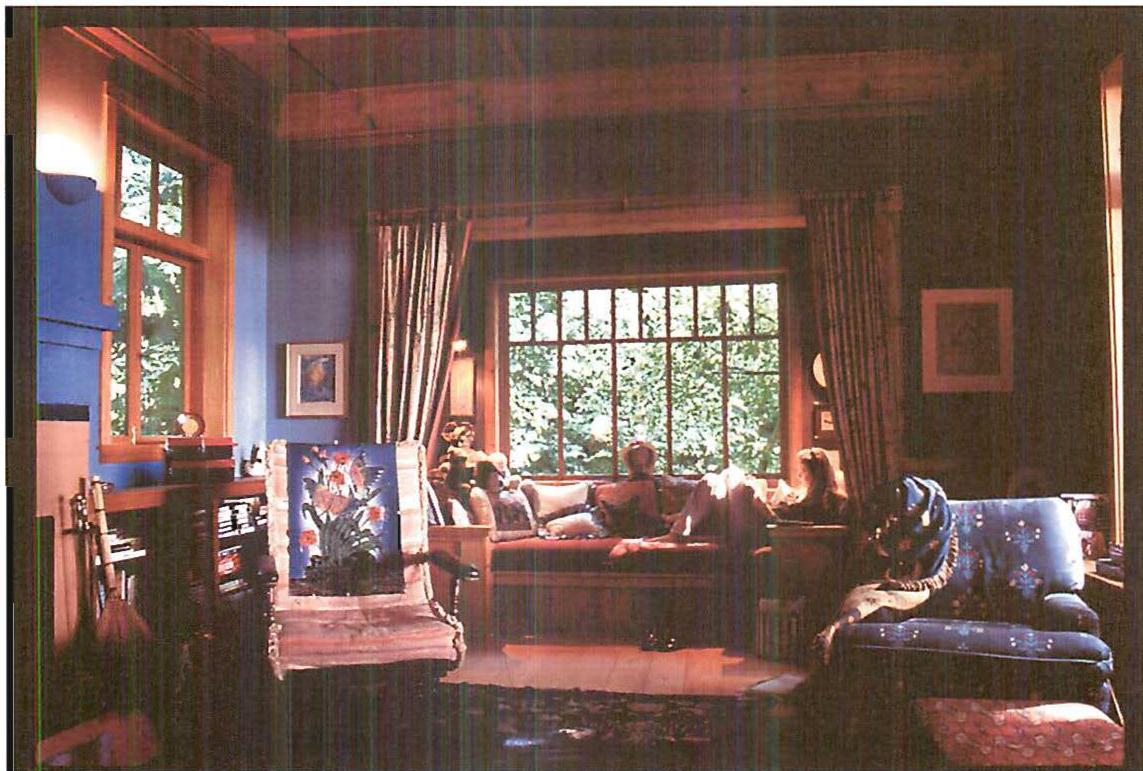

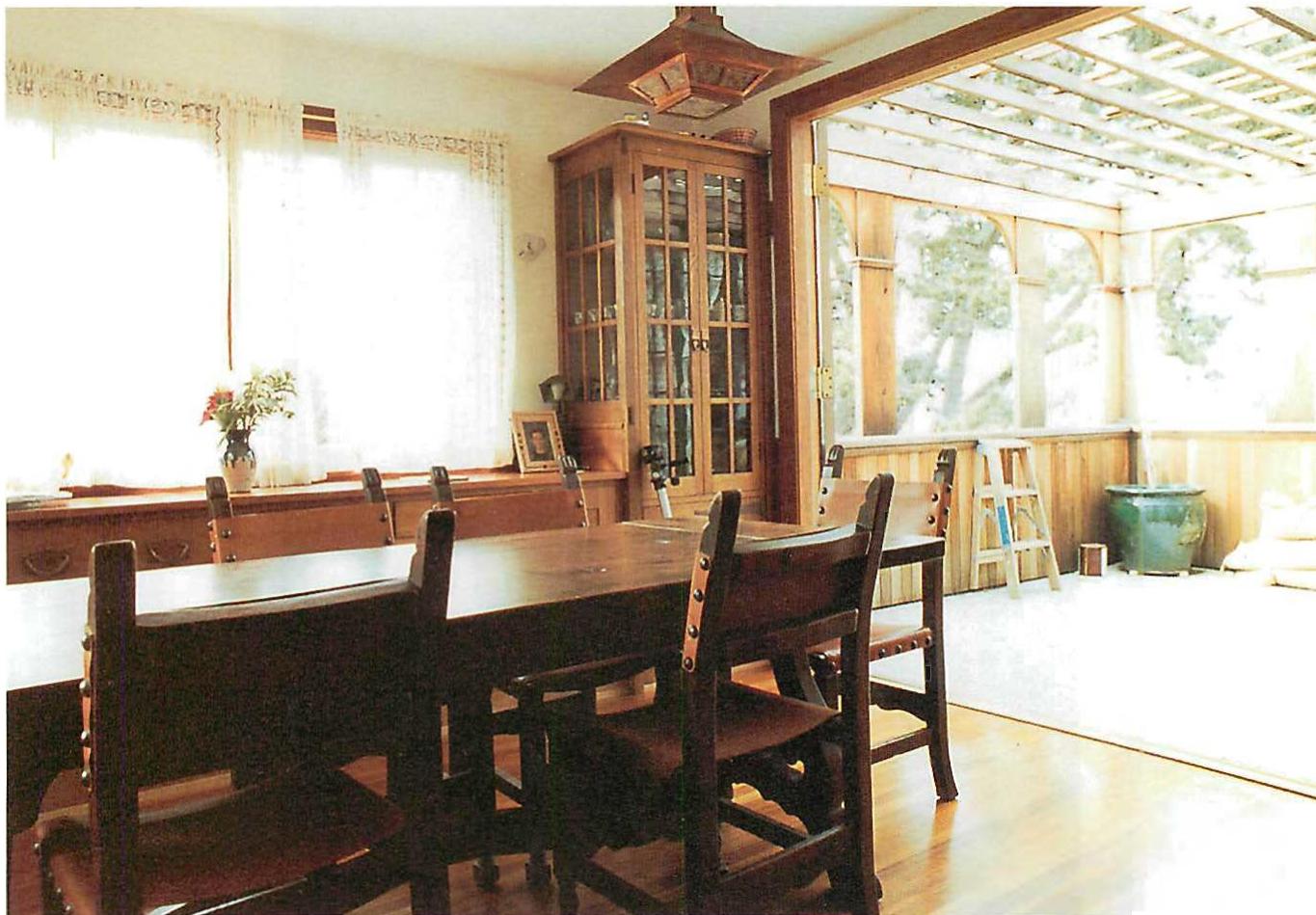

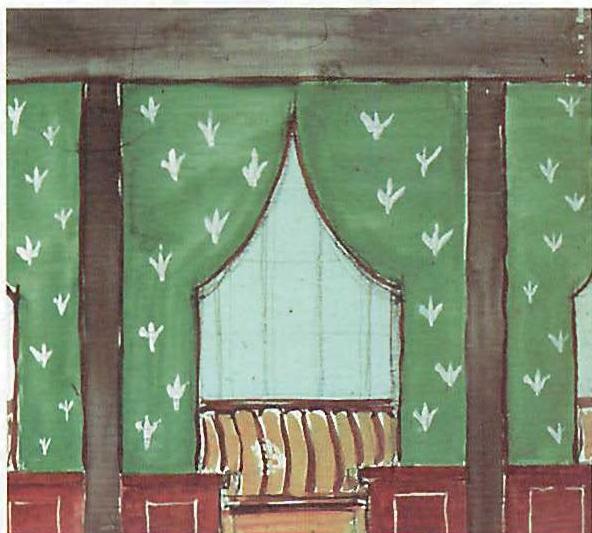

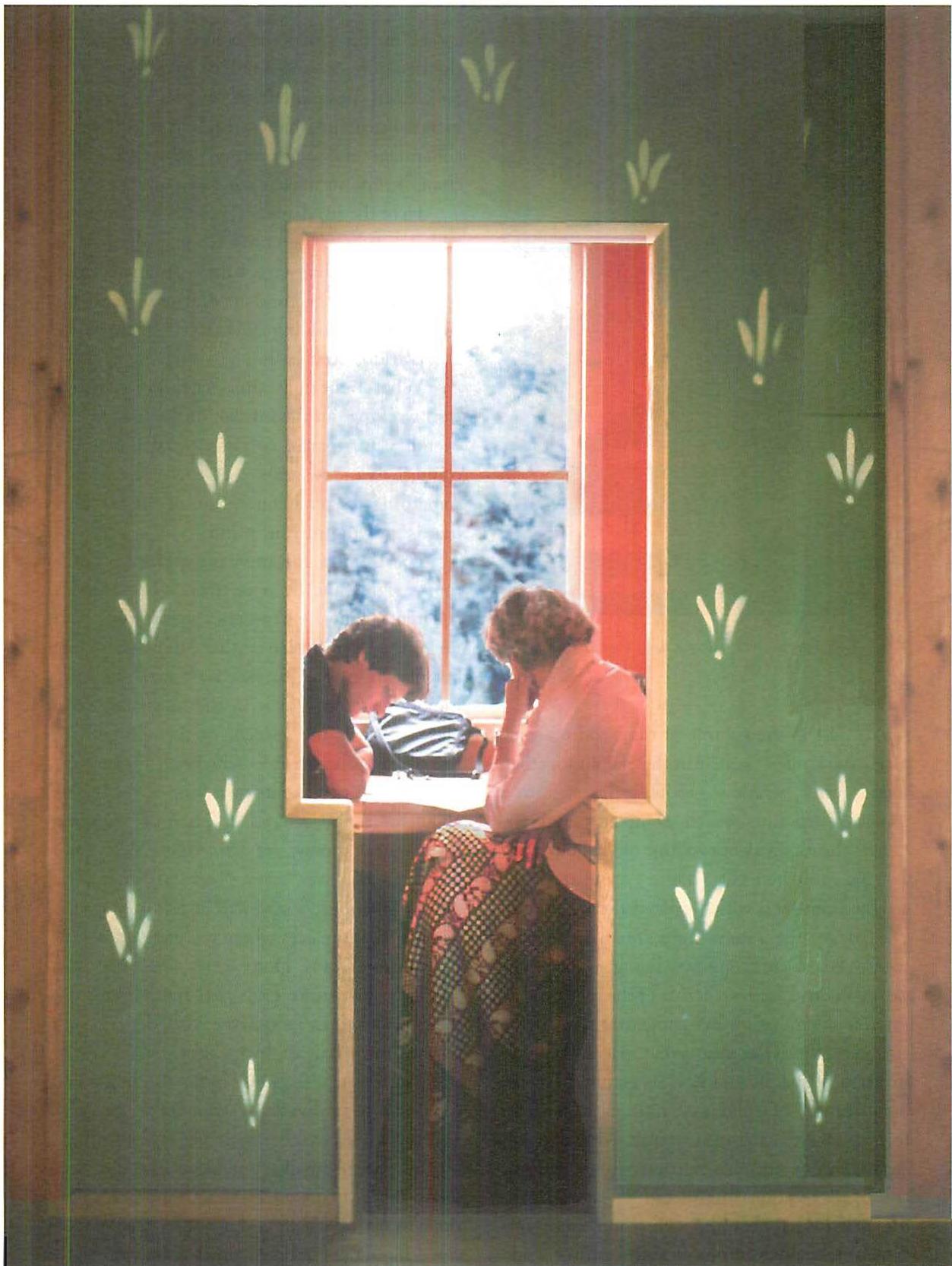

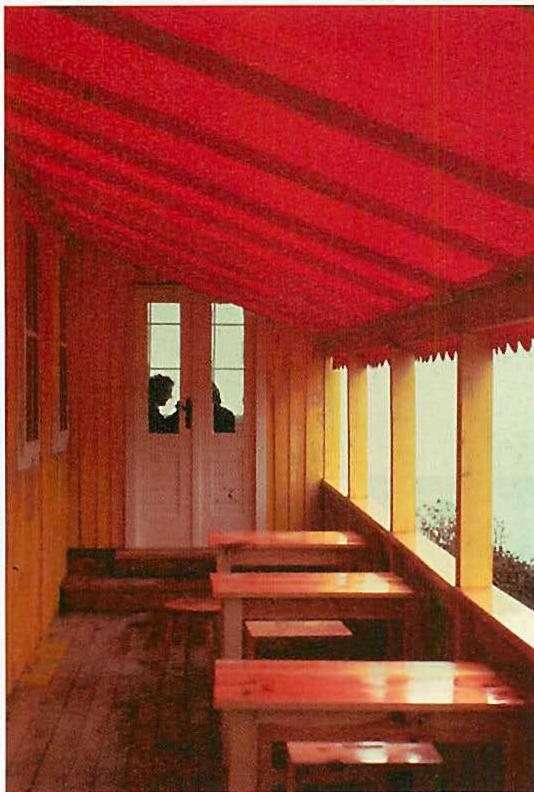

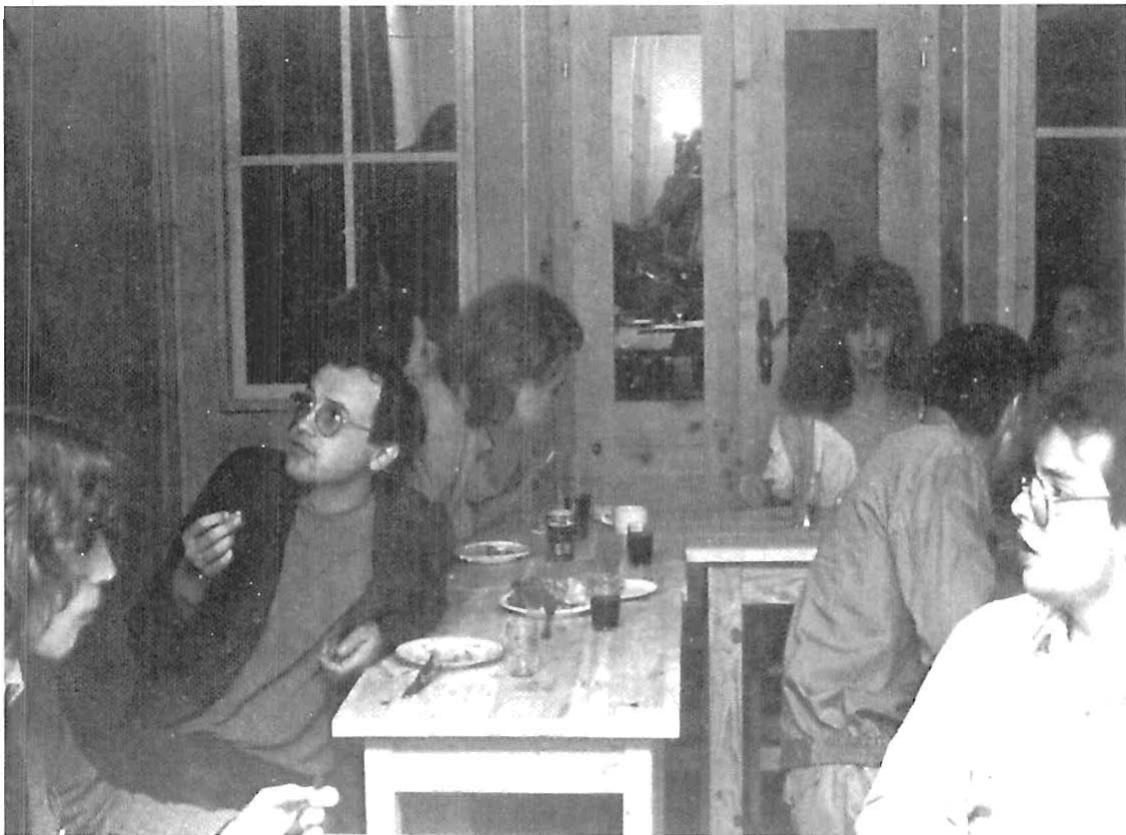

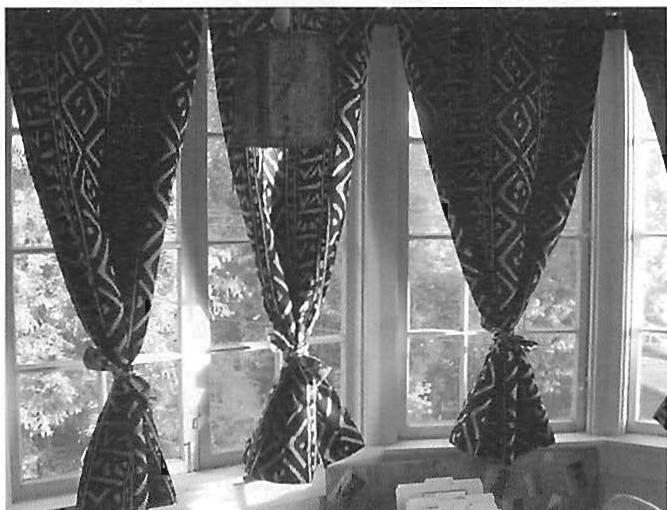

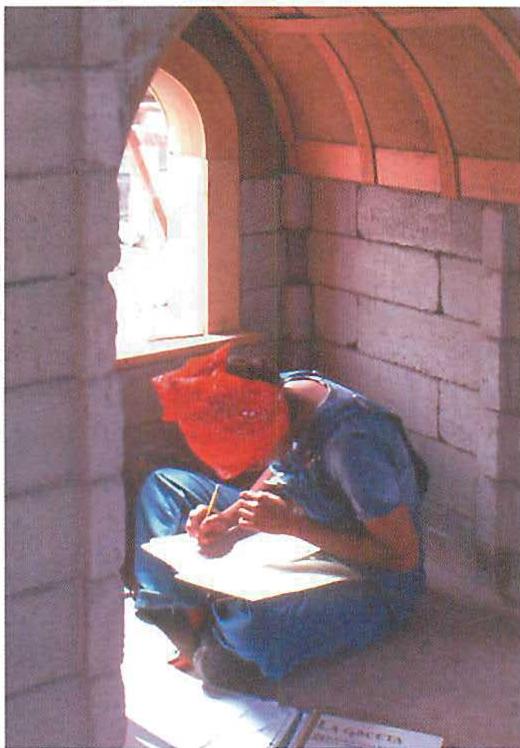

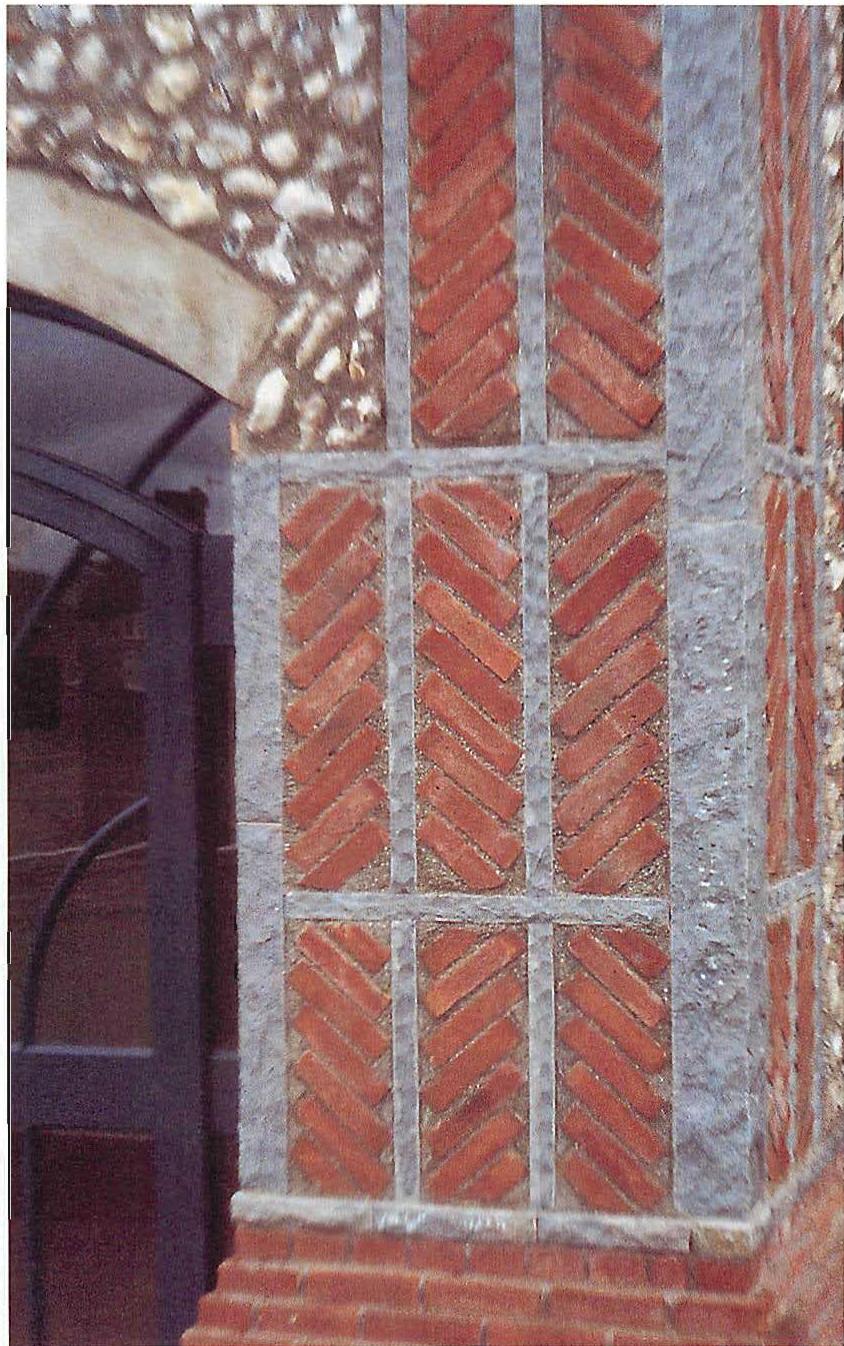

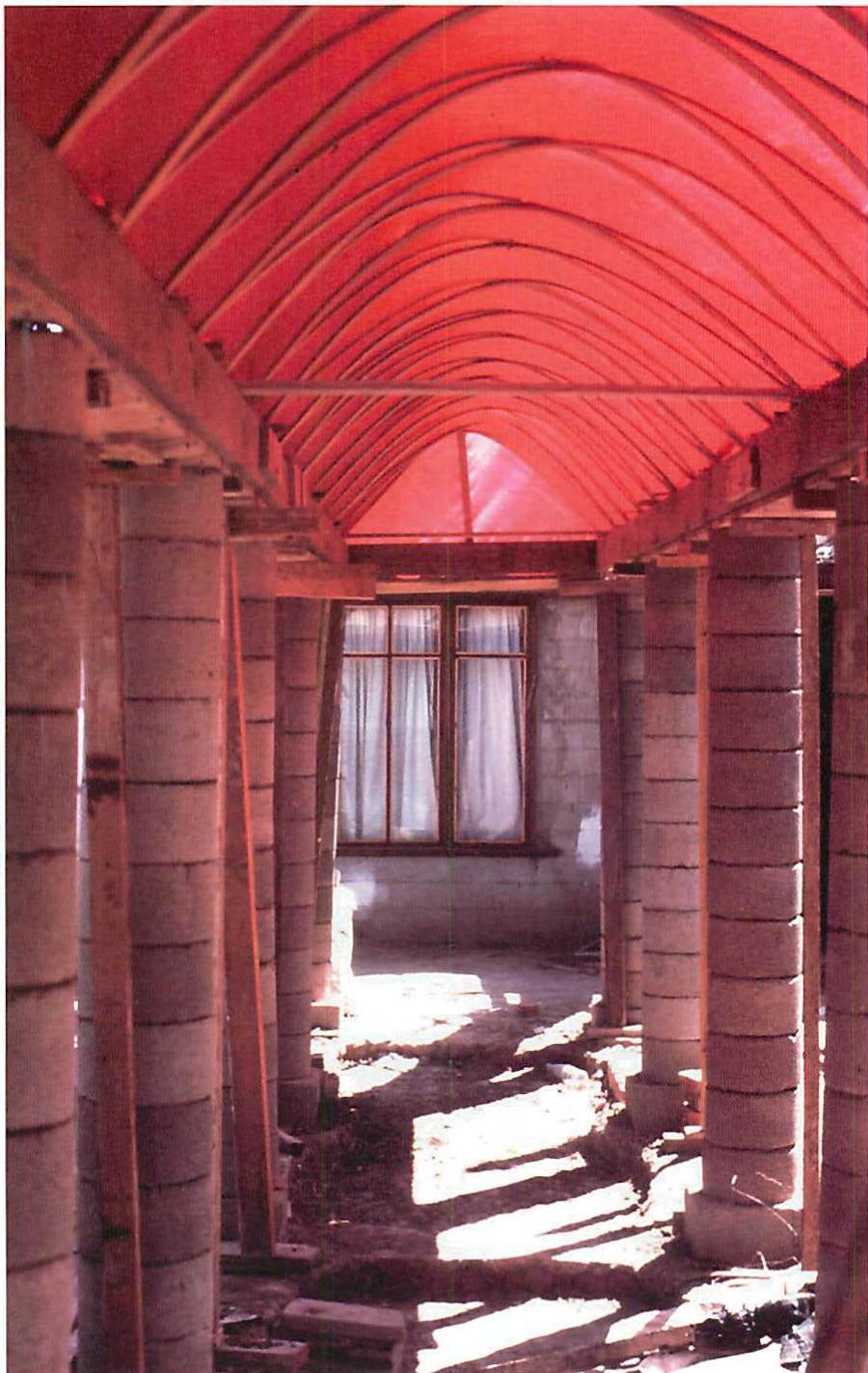

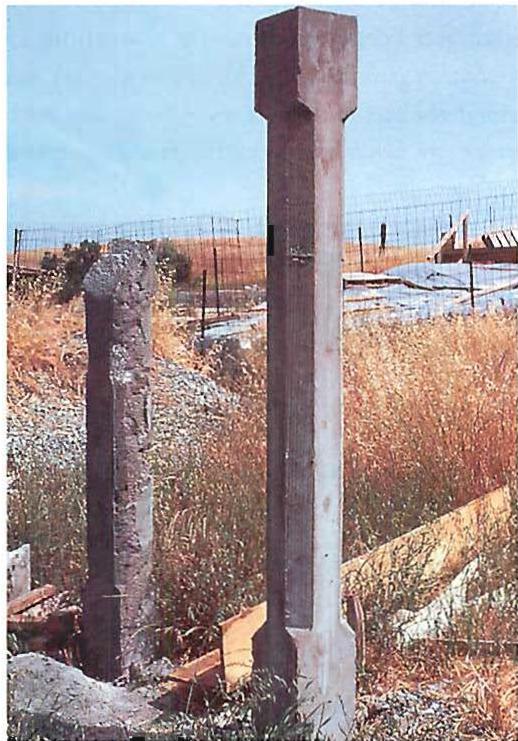

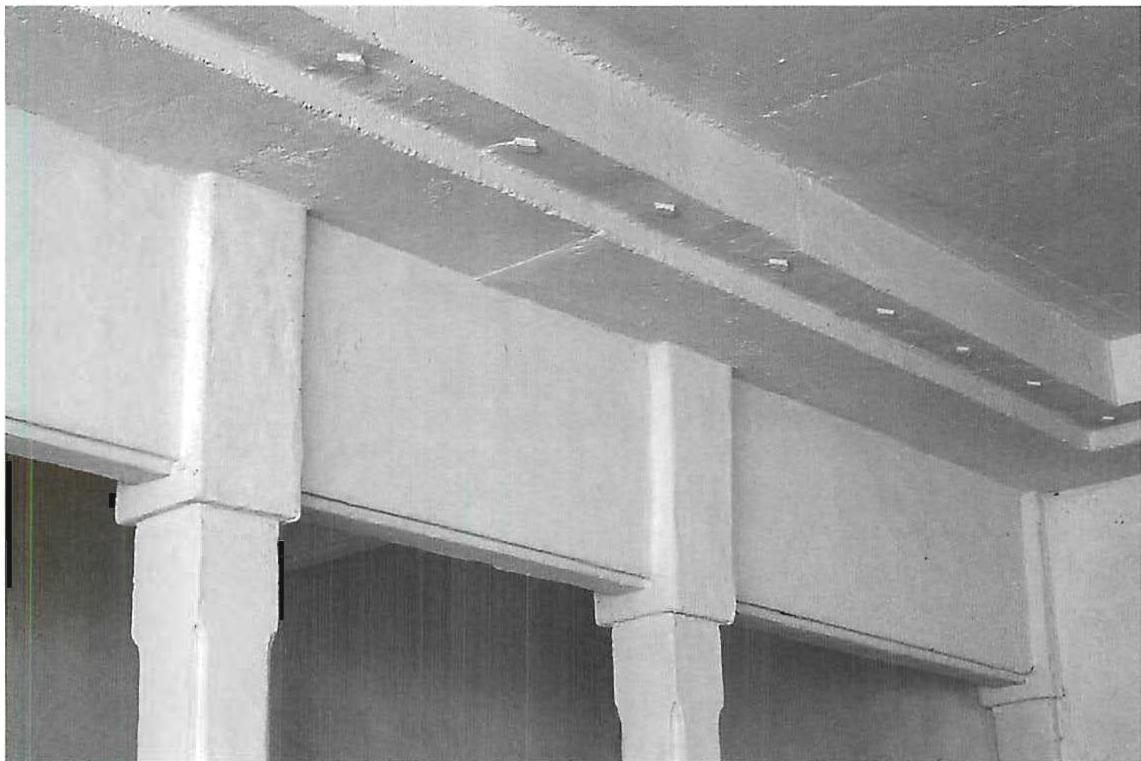

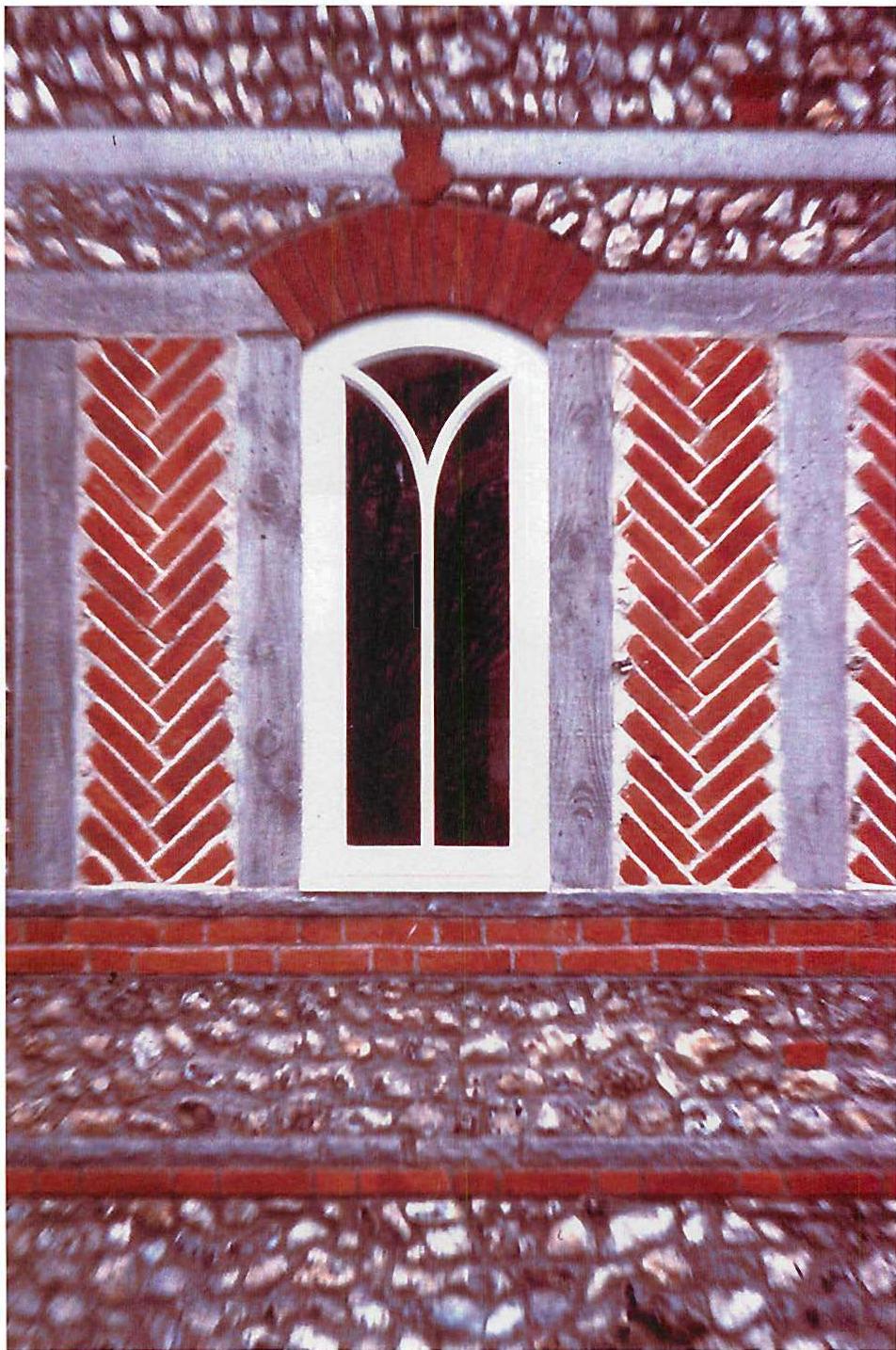

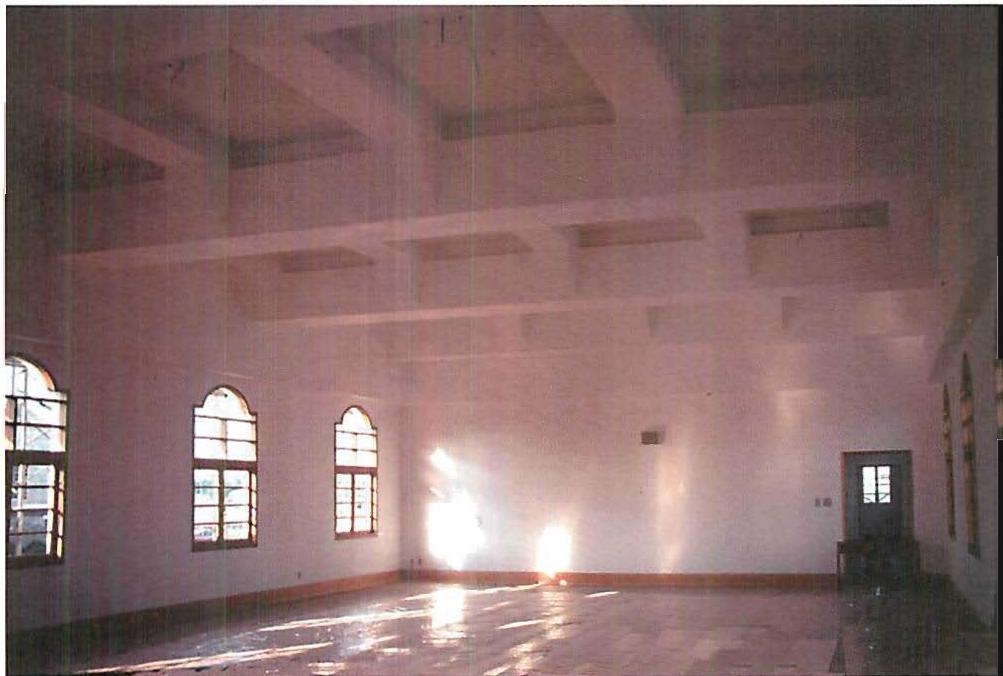

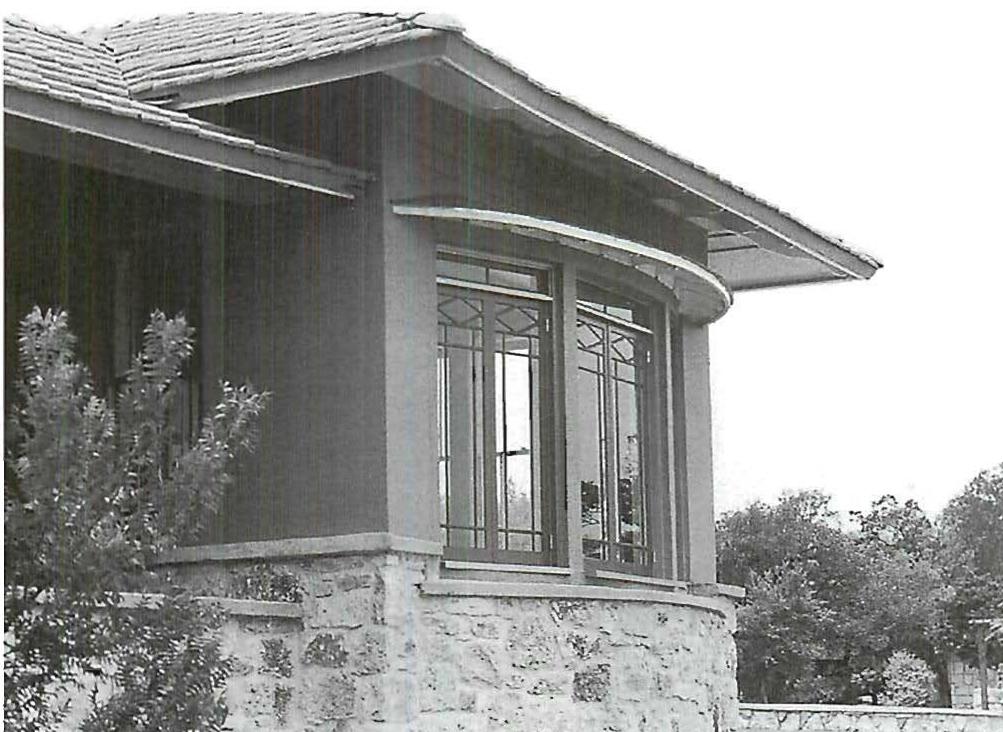

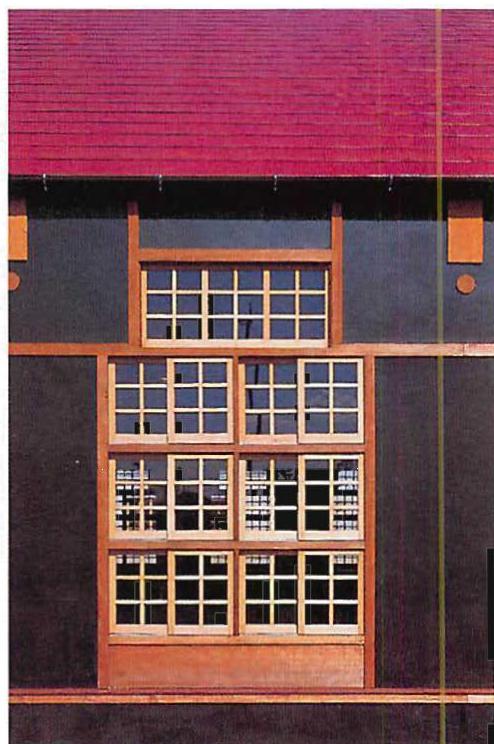

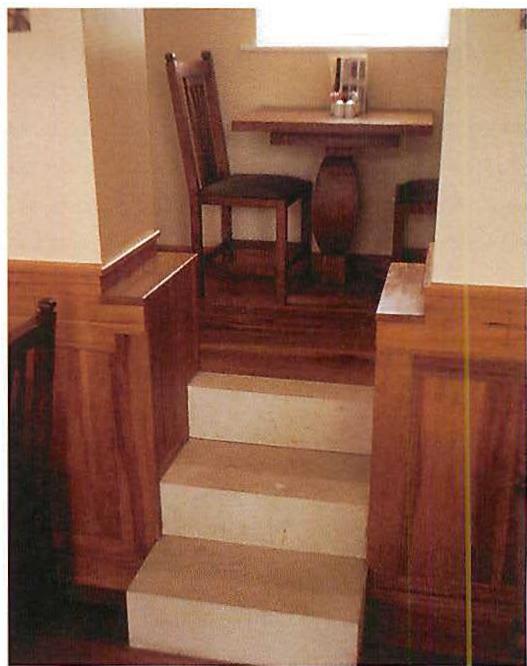

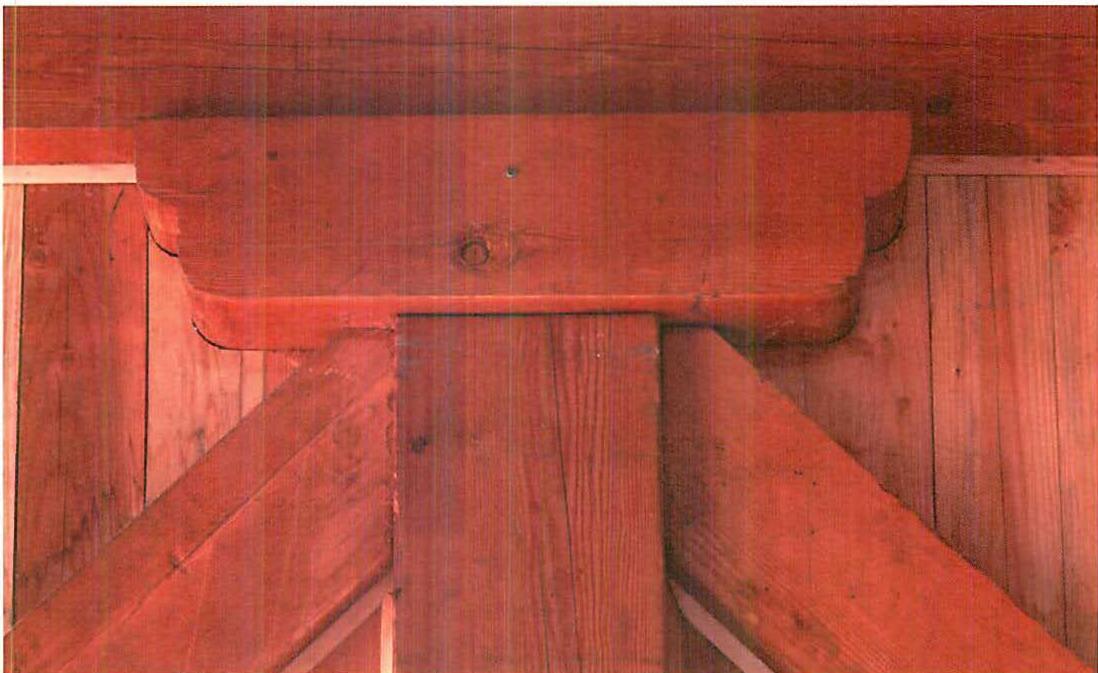

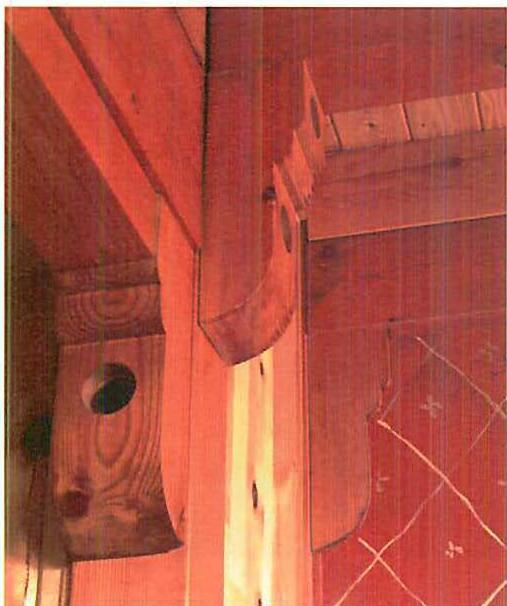

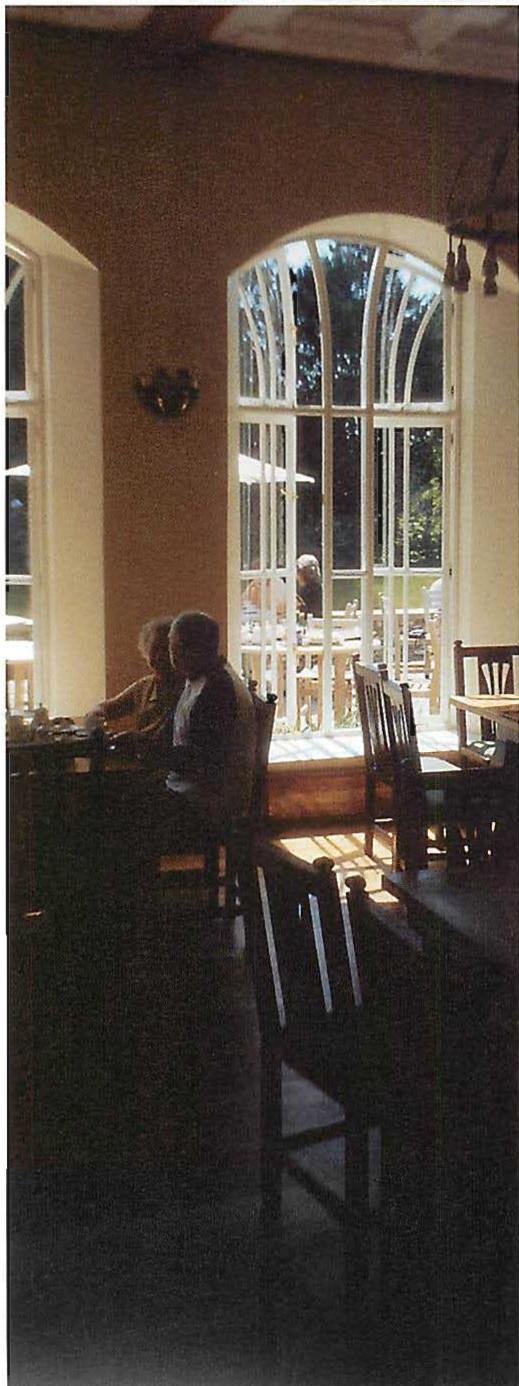

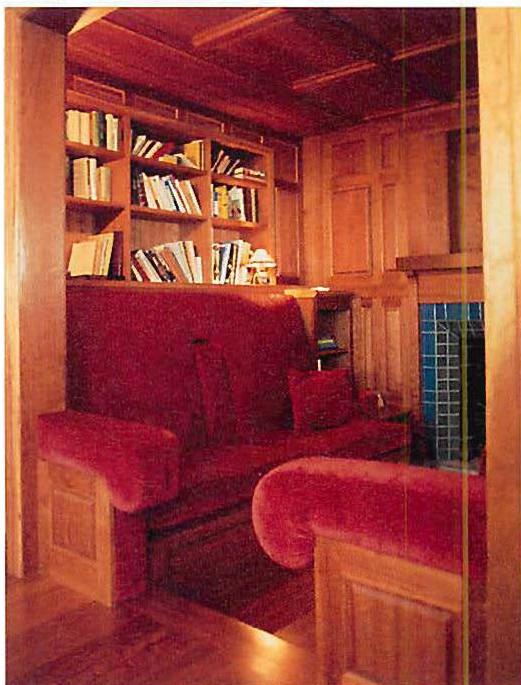

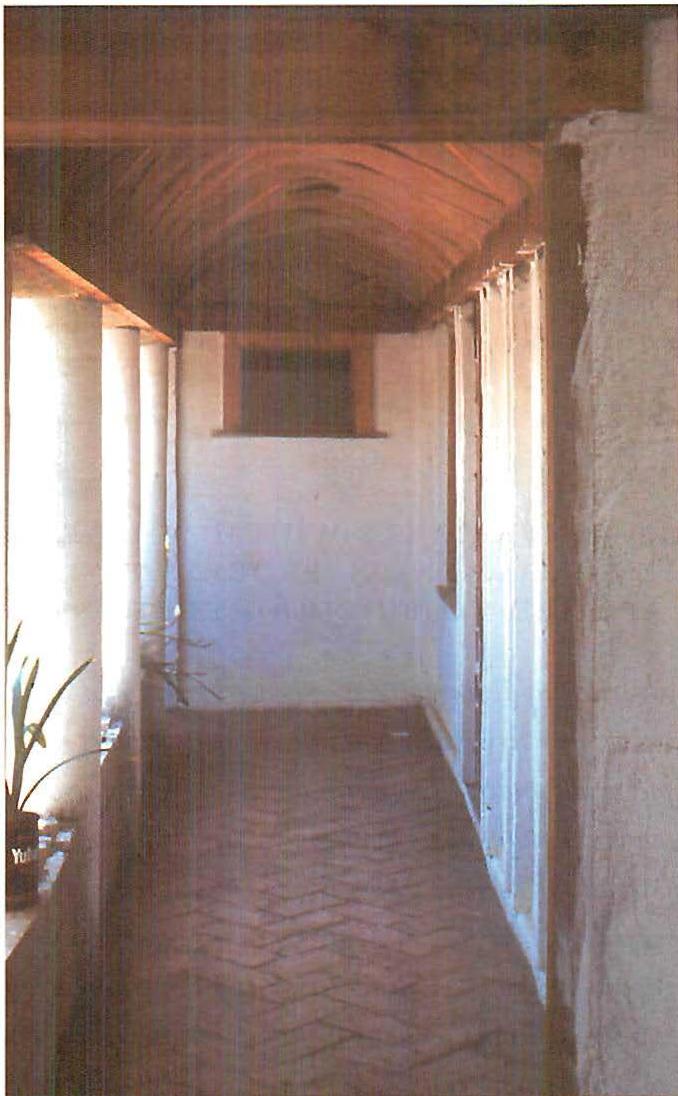

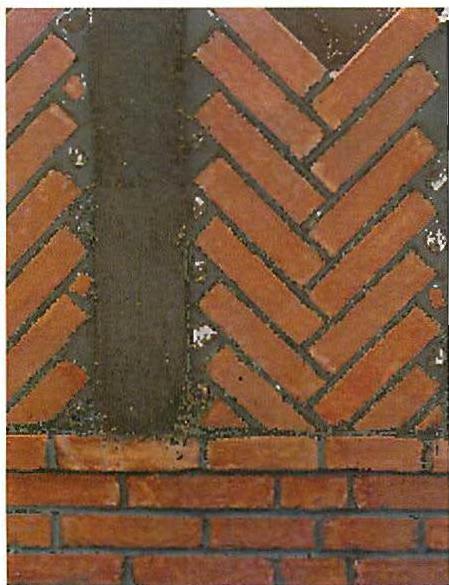

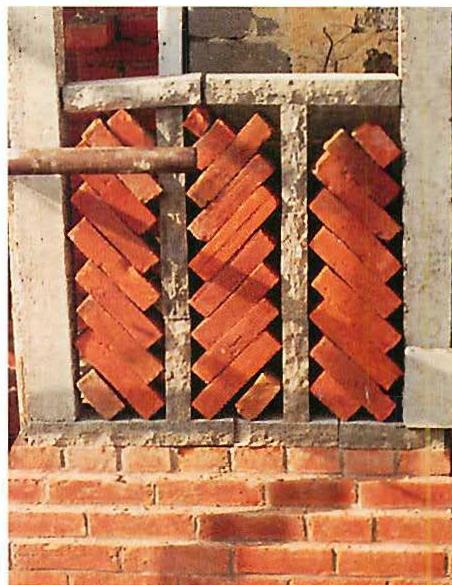

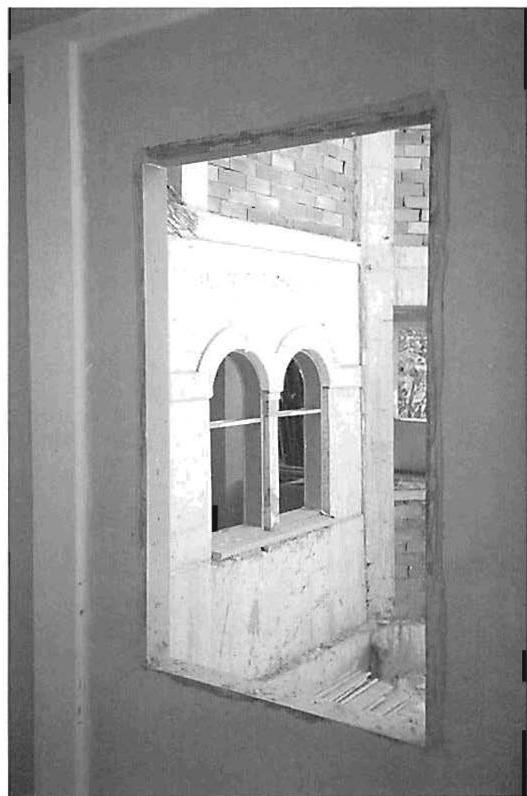

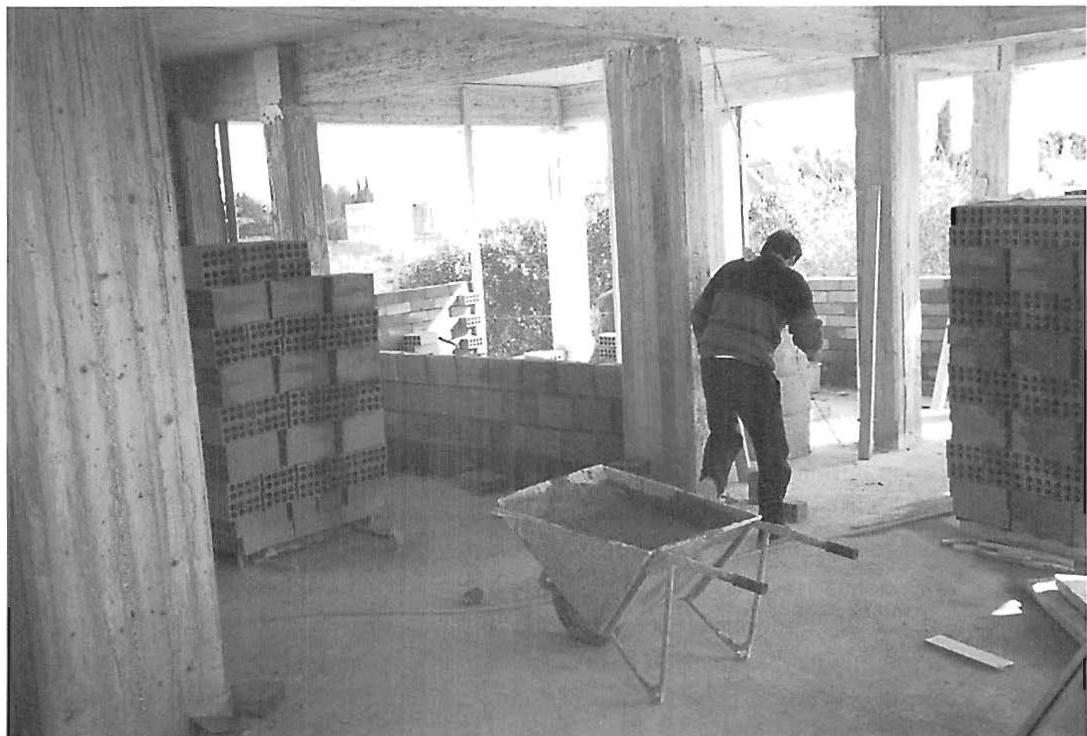

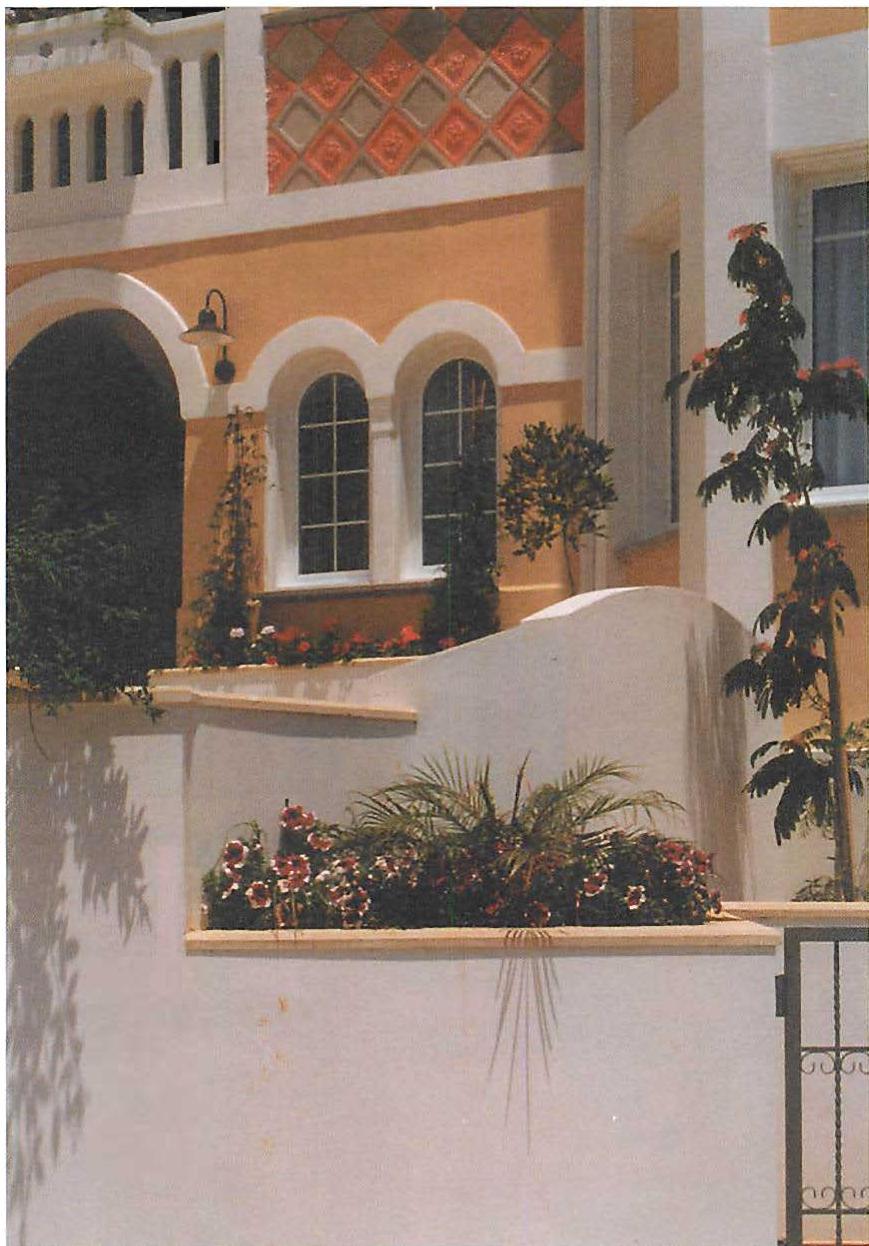

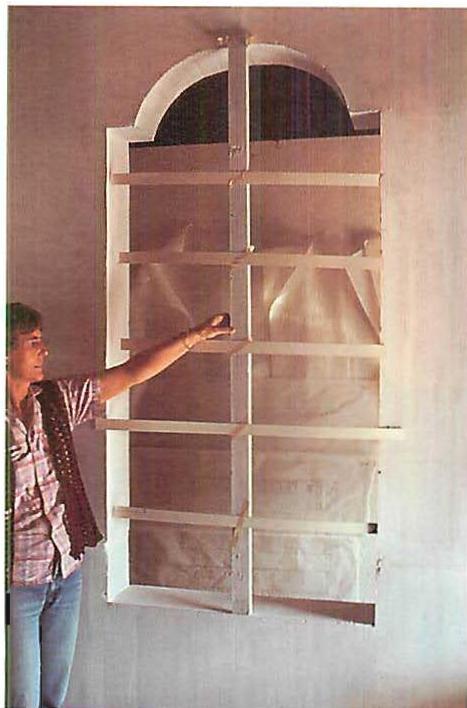

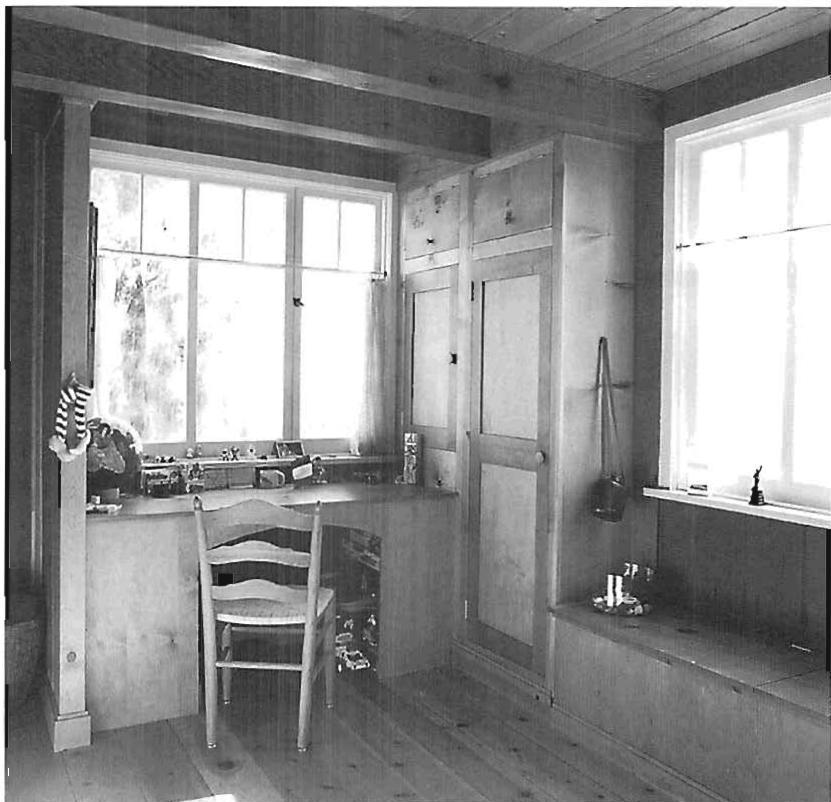

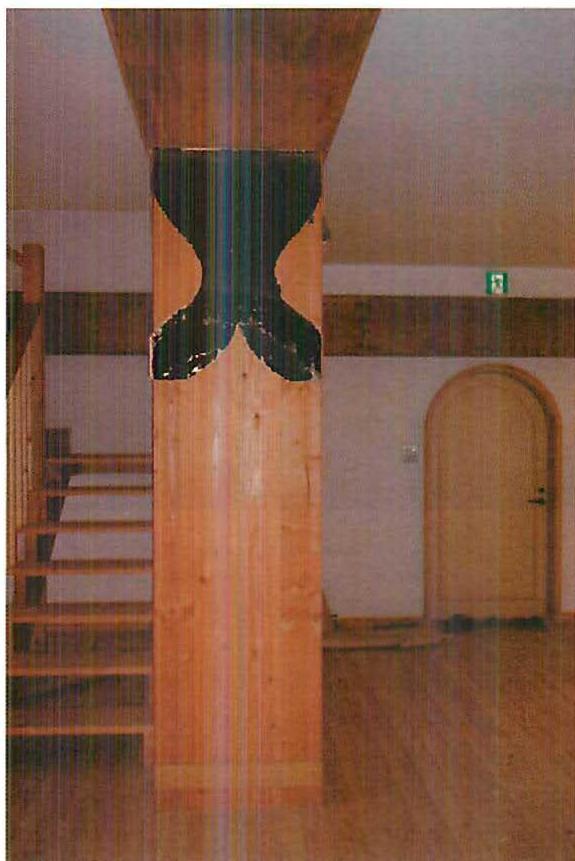

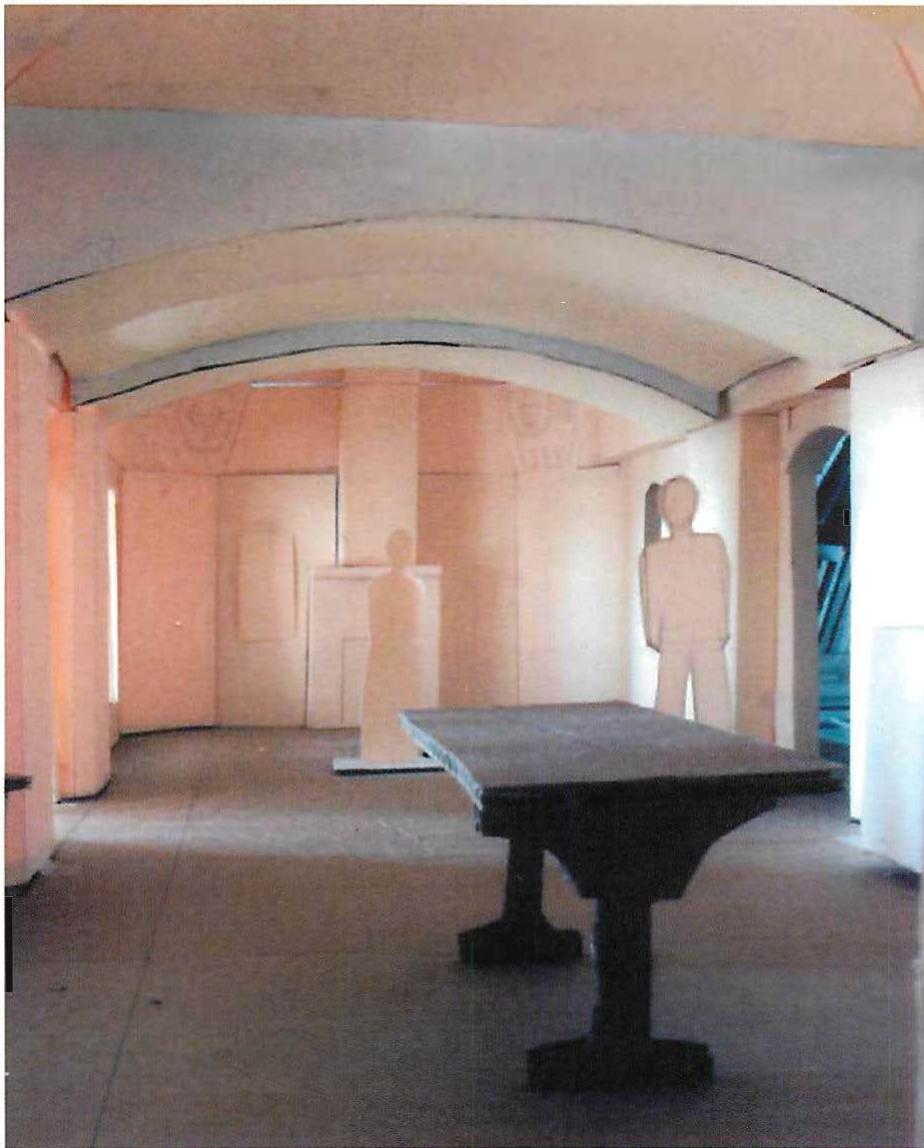

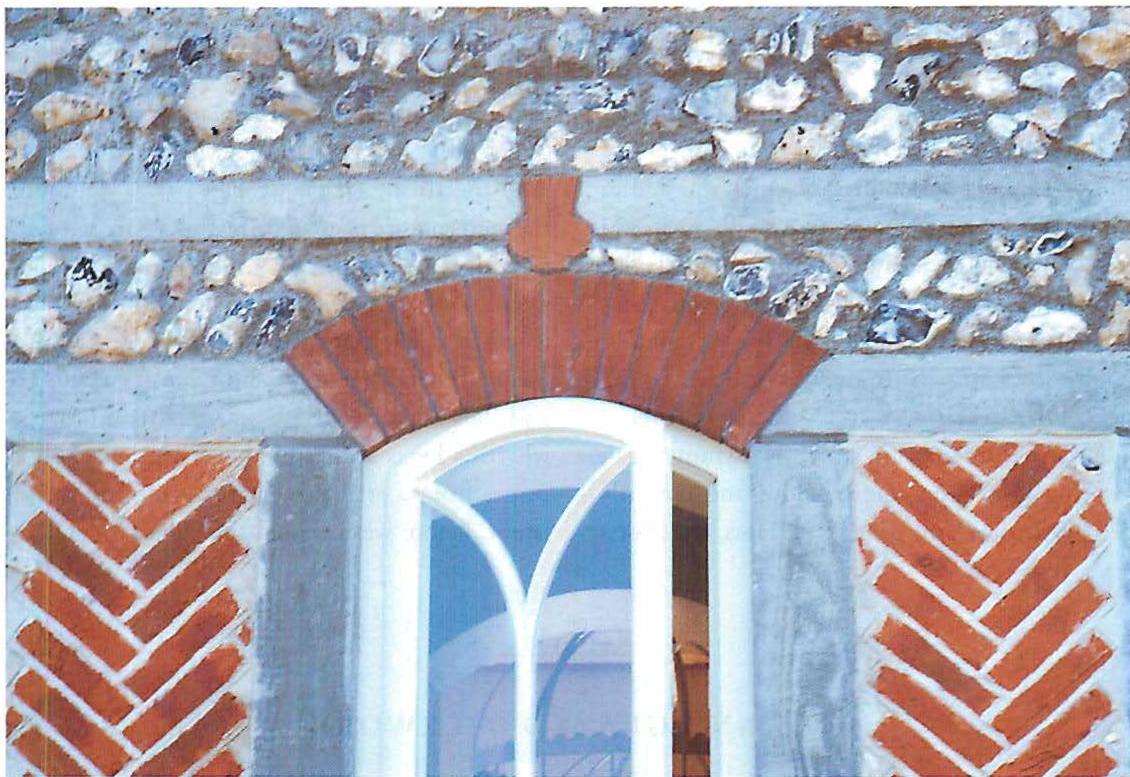

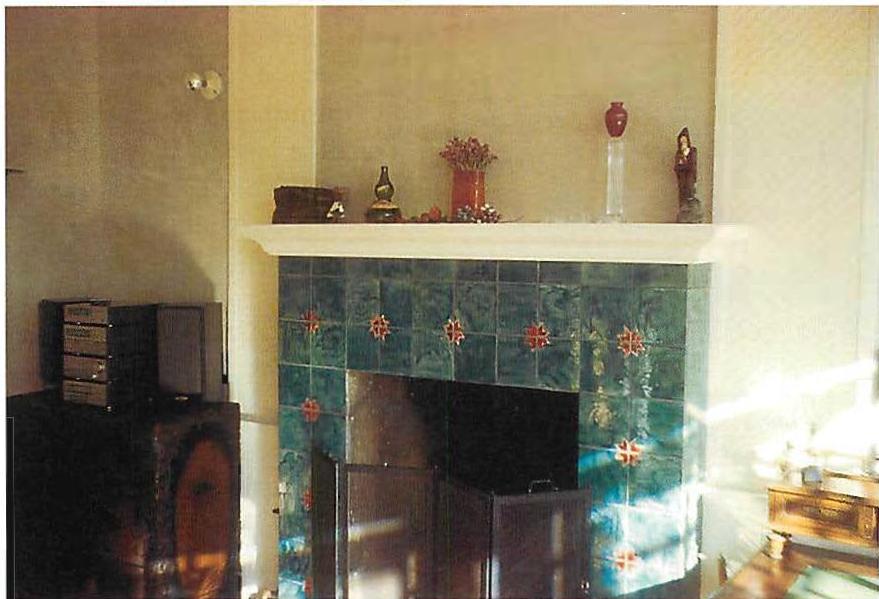

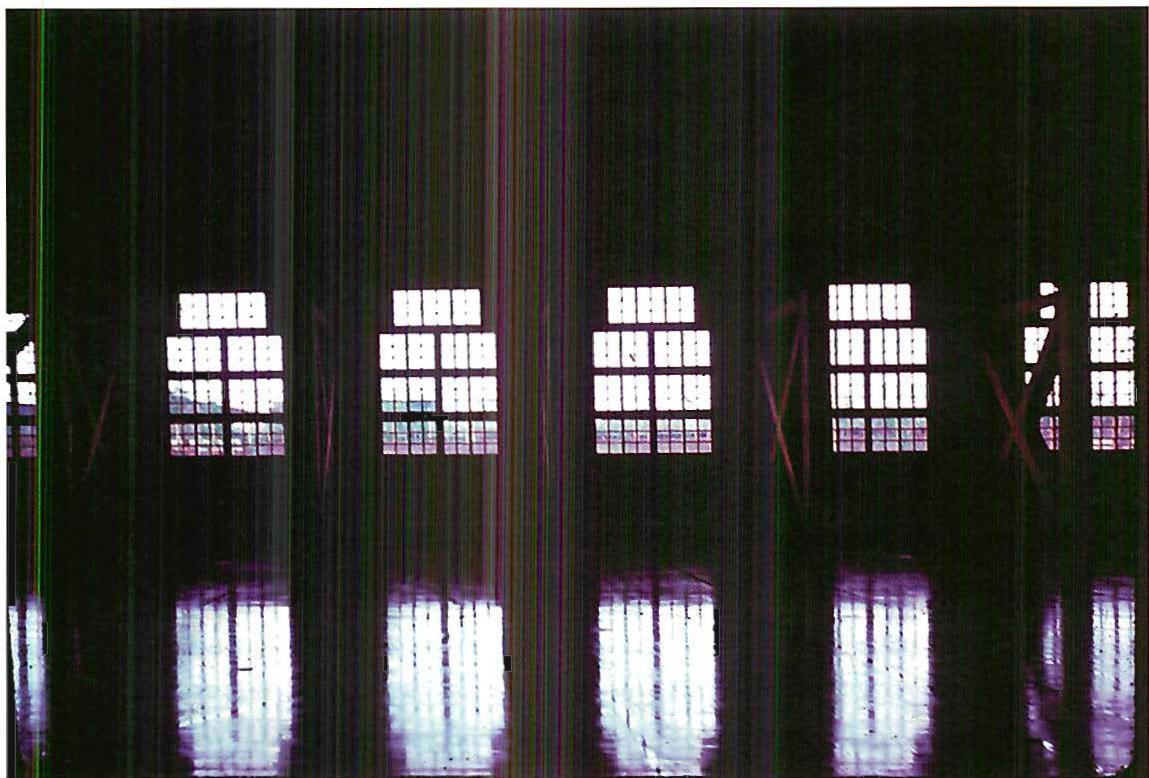

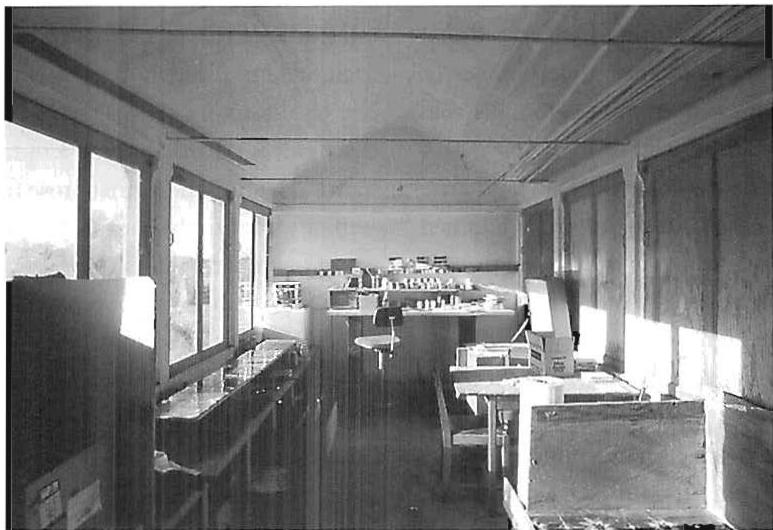

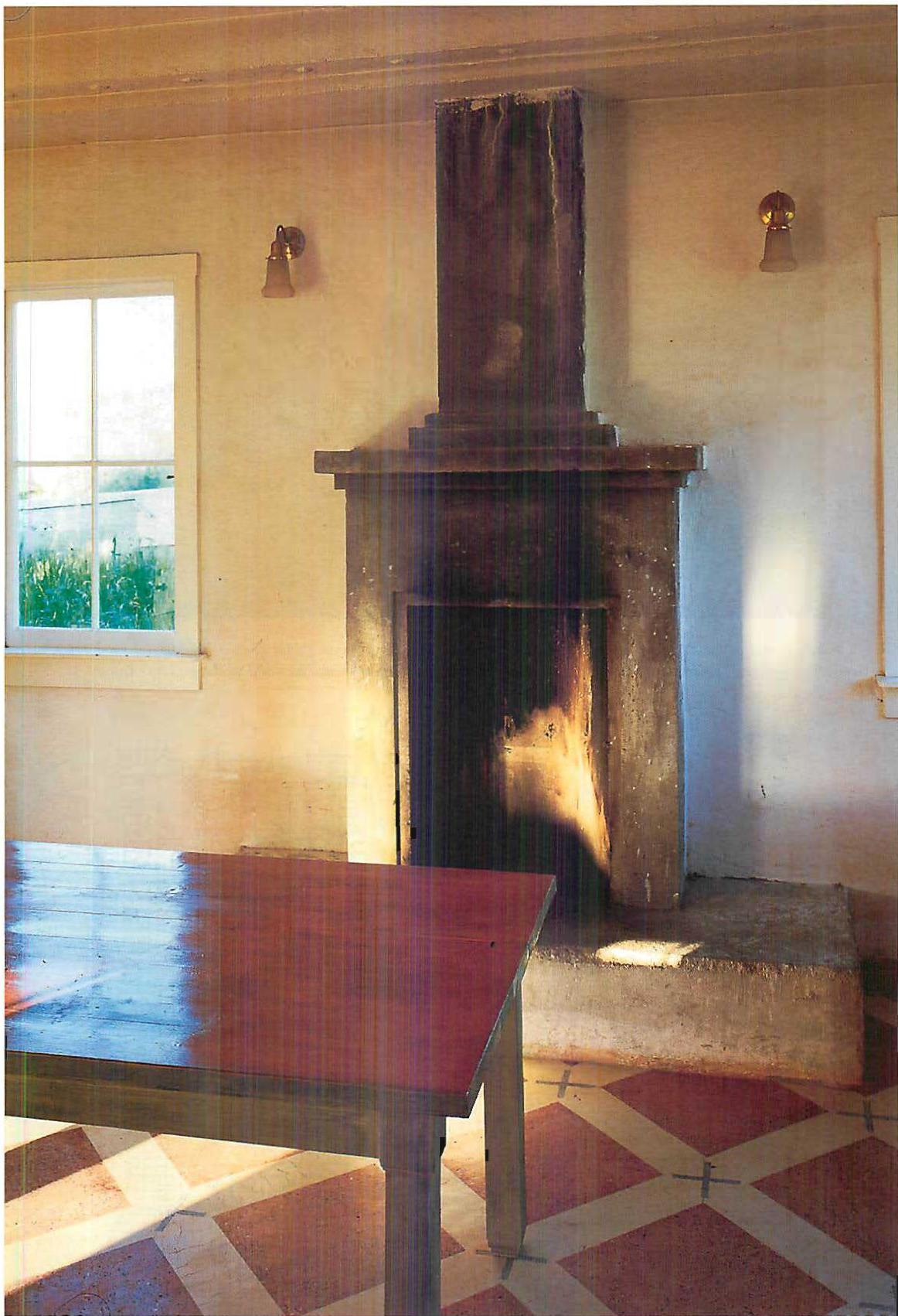

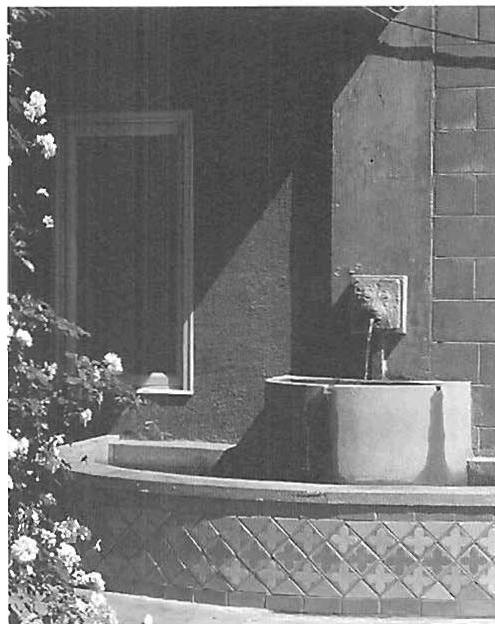

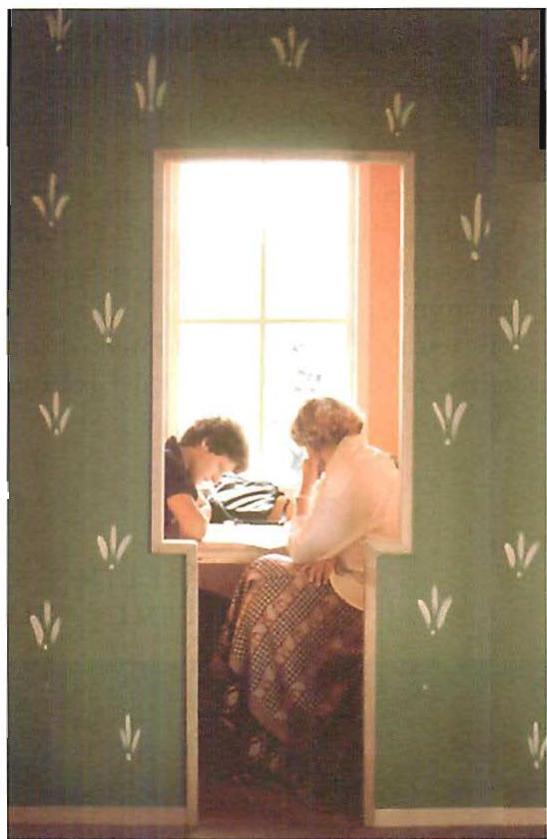

Some of the multitude of centers that were created in the West Down Visitor's Centre, West Sussex. Not only the beautiful windows, their arches, the fan shape of their glazing bars, the splayed reveals, but even the tables in the room, the table legs, the chairs, even the chair backs, all form living centers there — hence the profound harmony of such a scene. This was created by a multitude of living processes over time. Christopher Alexander and John Hewitt.

More generally, chapters 3 to 20 contain descriptions of the kinds of professional, institutional, contractual, and construction processes needed to bring such buildings to fruition. Each process is different. The variety of living processes is literally endless and one must learn to nurture this variety. Deep down, it is true that in all these varied cases we really need to be occupied with the system of centers and with the feeling of the whole — always. But there is nothing formula-like about the actual activity itself. Each living process, for each new project, is fresh and new.

5 / THE CONTINUOUS FLOW OF CREATION IN A REGION OF THE WORLD

Using the concept of living process, we may make a picture of the whole environment, natural and built, as something continually growing, continually developing, continually in flux, yet maintaining itself in a living state. We are familiar with the human body as something which exists in flow, not as a fixed object. The molecules in my body change constantly. After seven years, all the molecules — except those in certain brain cells — have changed. Much the same is true of a city or a neighborhood in the vision I am depicting. The city is being continuously built and un-built, rebuilt, built, destroyed, modified, built, added-to, improved, destroyed, and rebuilt again.

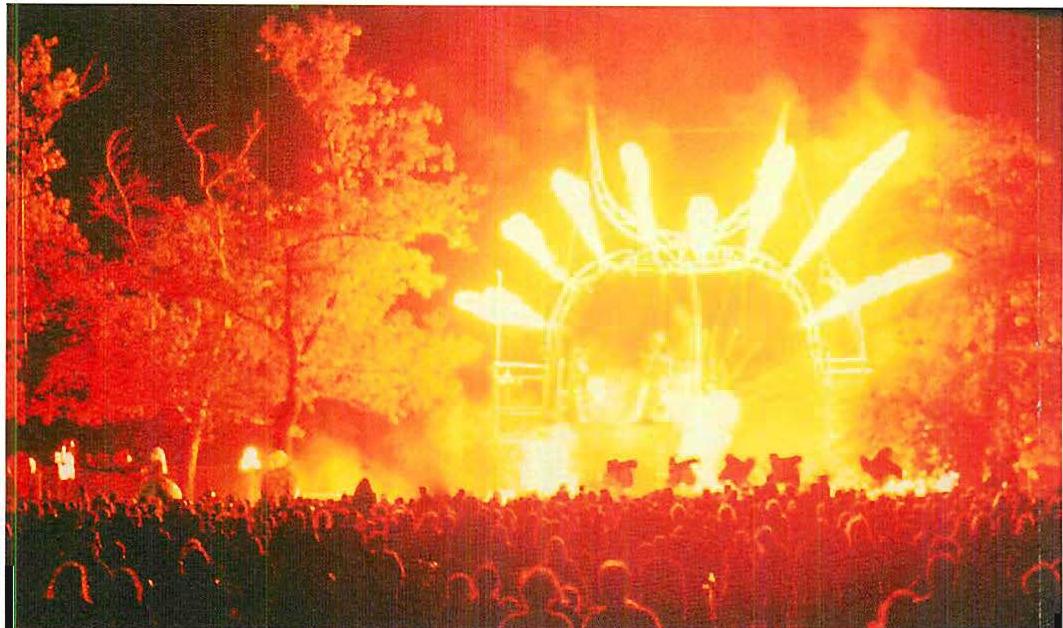

Imagine this single process, this unfolding process, endlessly repeated, always creating centers, always unfolding the existing wholeness. This process, like some imaginary needle carrying a single thread, but in a thousand hands, dipping down, now sewing a seam at the largest level, now dipping down to some detail, now plunging across the thread to stitch the middle-level seams.

What I offer you is a conception in which all of these acts of repair, design, construction planning—all of them, large or small, local or global—are guided by the fundamental process.

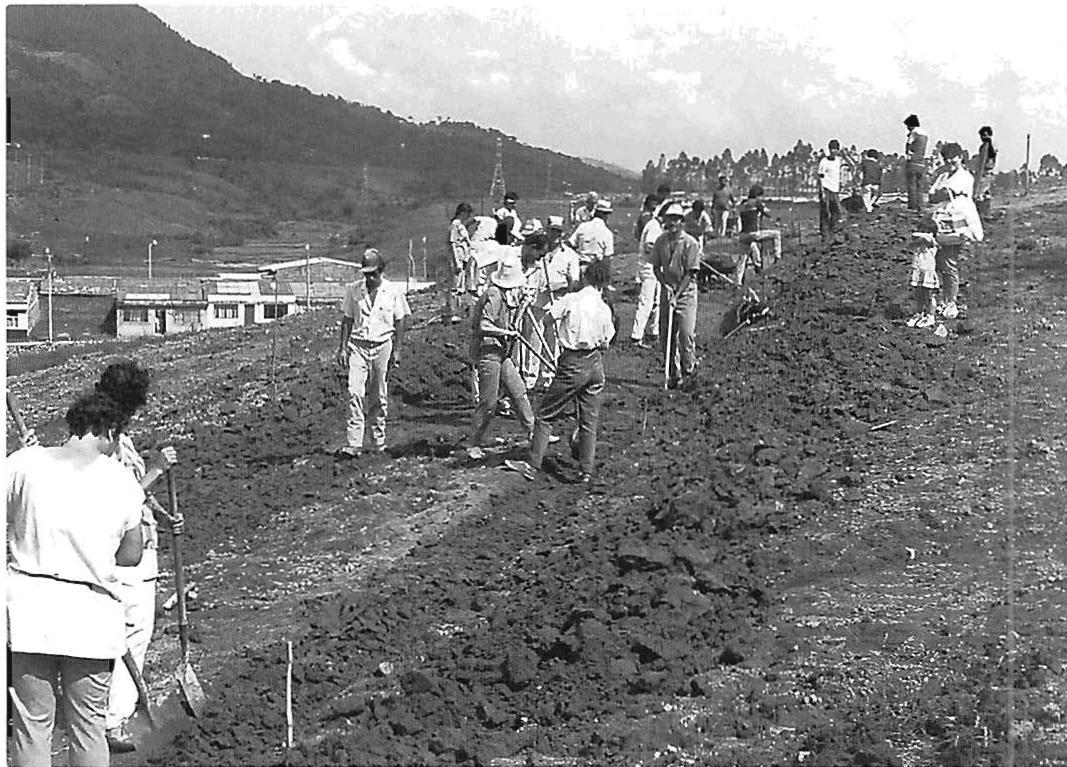

Of course a city is built by millions upon millions of acts, by millions of people. If we try to list all the different man-hours of construction labor that continuously create a city, it comes from millions of different sources. It includes the professional construction labor of the construction companies. It includes the public works department fixing roads. It includes the telephone company placing and replacing telephone cable. It includes agriculture. It includes people working in their gardens. It includes someone painting the fence on the weekend. It includes cleaning the house, sweeping the house, rearranging furniture inside a house. Thus the environment is built, and rebuilt, from a colossal number of different kinds of operations working together, continuously, to build and rebuild the city.

What we think of as the city, in its life, is the continuous flowing whole which is created and recreated daily by all these events together.

If the city becomes alive, it is because these processes governing various small bits and pieces — many of them together — are creating life locally. But because the fundamental process has, at its core, the idea that the life of any center only comes about when this center is making life in some larger center, by definition, then, the coherence spreads upwards and outward, from each small act of construction or repair, to the larger entities that are being nourished and created.

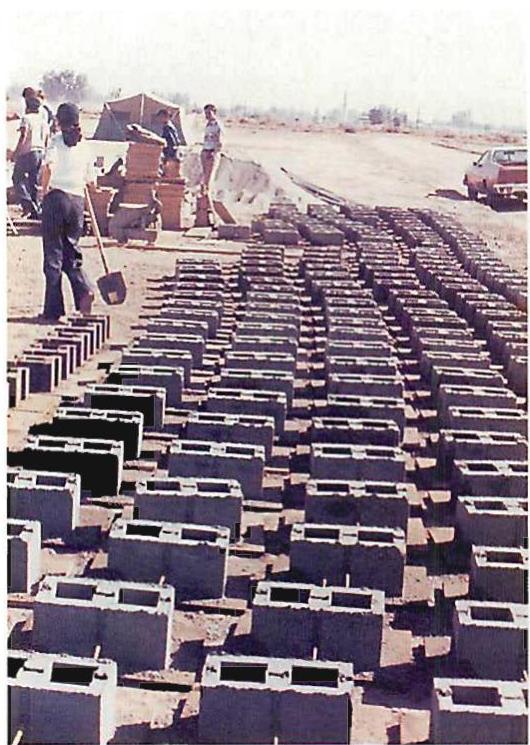

The process can be highly variegated. It can include agriculture, road-building, new construction, people repairing and rebuilding their houses, engineers building bridges. It can include someone buying and installing a lamp in the kitchen. It can include someone who paints a picture and hangs it on the wall. It can include the plowing of the fields and the pruning of the trees. It can include installation of highway signs, industrial development, manufacture of tiles, a thousand people painting their front doors.

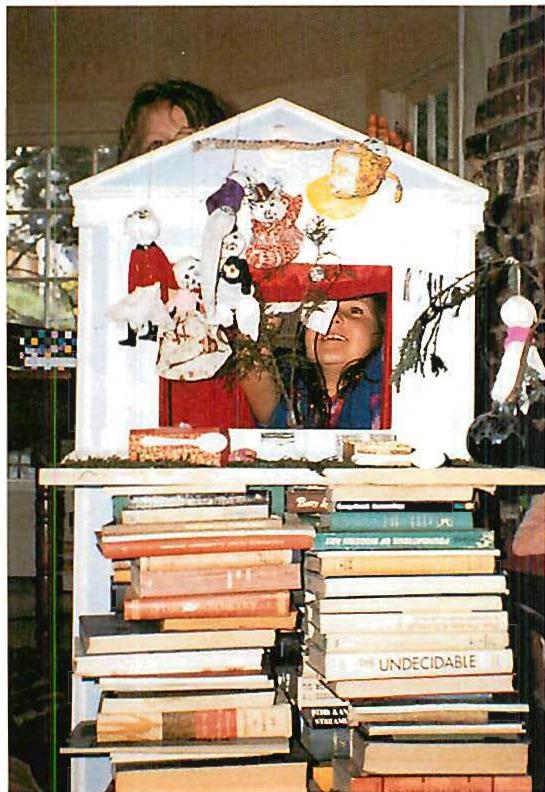

This vast and variegated process may contain, as sub-processes, thousands of individual processes of thought, design, art and construction. It can include the making of individual buildings. It can include the process of someone planing a board. It can include someone painting or carving an ornament. It can include the human process by which a group of people sit down together and plan their neighborhood: and the more modest process by which they sit down together to decide which tree to plant at the end of the street. It can include, of course, the rather

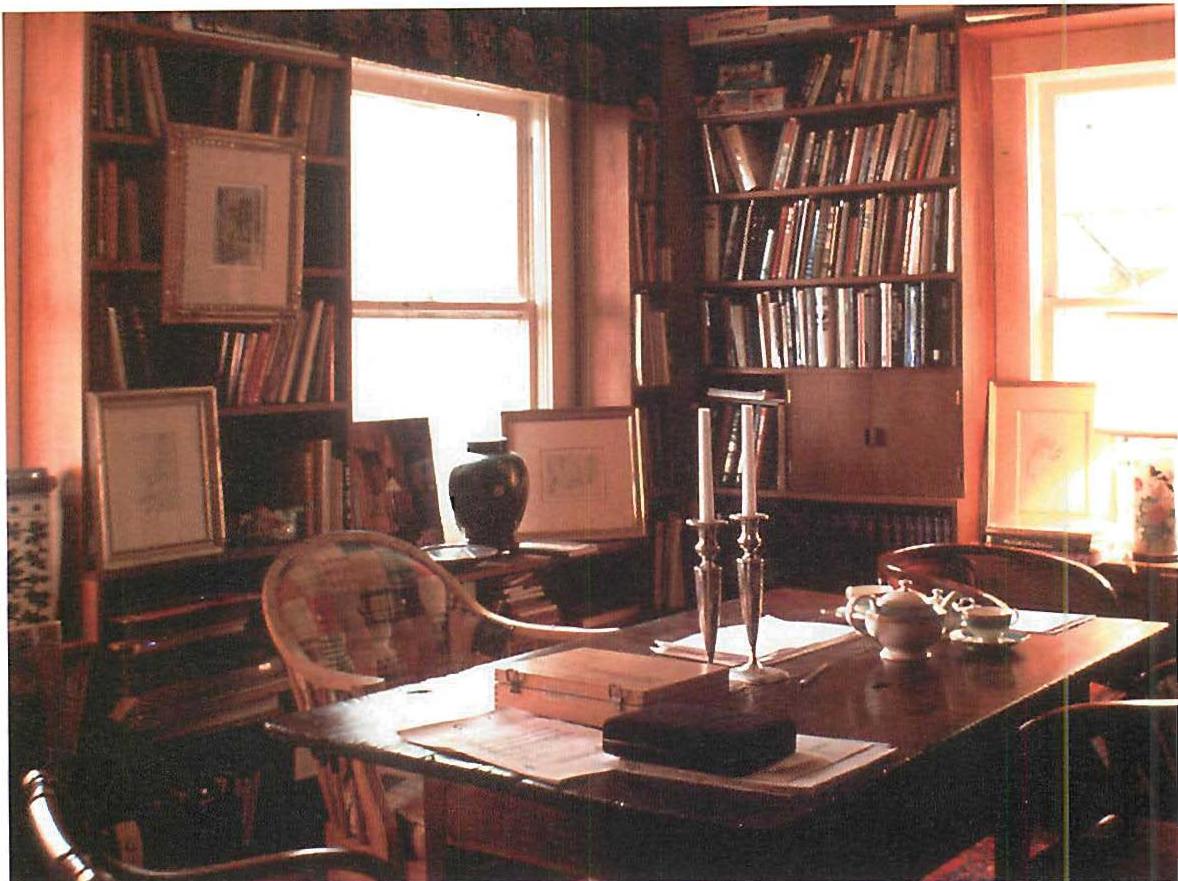

big and imposing process of building large and important buildings. It can also include the more delicate process of furnishing an individual office or a study in someone's house. It can include the placing and building of a bench by a fish pond. It can include, too, the act of stocking the pond with fish, and the act of planting a bush beside the pond. It can include, even, pruning the bush, fertilizing it, sweeping away the leaves.

And the process also includes, of course,

what we normally think of as destruction. Cutting down a dead tree, breaking out a piece of abandoned roadway, demolishing a derelict building—all have their place. Clearing and building go forward together to create and maintain the world.

This huge process of order-creation contains millions of strands. Yet it is, in the whole, a single process which can move forward to create and maintain the health and structure of the world.

6 / WIDELY SPREAD LIFE-CREATING PROCESSES

From the material presented in this book, I hope that you may get a glimpse of what is possible, a goal, a target, a hopeful sense of our beautiful and comfortable Earth as it may be in the future, and where we may one day more deeply make our home.

It is true that what I have accomplished is modest. But, for nearly forty years, I have been building, planning, making works of art and craft—all efforts, in one form or another, to test the idea of living process in the real world and to see what can be accomplished by it.

I have tried to build a body of evidence, a body of building where people may see a new spirit, a new way, a new atmosphere.

Above all, I hope I can convey to you that what I call living structure not only is more beautiful, more alive. I hope that I can also convey, and sometimes even demonstrate, what I claimed in Book I, namely, that this kind of structure supports human life better than other structures. When human beings are part of a world of living structure, they can sometimes reach the best that they are capable of, sometimes become free to be themselves.

People say that what I propose is difficult to do. But I have been doing these things for a long time, trying as hard as I could, often succeeding, though admittedly often failing.

From thirty years of experiments, some described on the following pages, you may see something of what can be accomplished. The hundreds of completed examples in the pages which follow also show how it can be done. I show six hundred pages of built examples to convey to you that life-creating processes are general, can cover inconceivably many problems and situations that do occur in different cultures and different circumstances, and still create coherent structure as a result. I hope that you can extrapolate from these few hundred pages and invent thousands of new processes of your own.

In each case of a new process that you yourself initiate, the details—what makes it a living process—are likely to be different. That, too, is part of what I want to demonstrate. It is important to understand that one has constantly to be inventive. Life-creating processes take an endless variety of forms; there is no way we could exhaust the forms of all possible processes, and this book is not a catalogue of possible processes. It is only a tiny sample of a universe of very different processes, all in some measure embodying some combination of the fundamental process repeated many times.

Nevertheless, each chapter does show, matter-of-factly, some of the features which are

likely to follow from a general use of living process. In a sense, the nineteen chapters as a group cover the main features of a world generated by living process. I have focused attention on the particular features which follow when living process is applied to them because, together, they

encompass some—not all—of the more important architectural consequences which come inevitably from repeated use of living process.

The examples show why this "new" character is likely to appear whenever living structure is allowed to unfold.

7 / CONCLUSION

I would ask you to come back, for a moment, to the title of this preface. I have called it LIVING PROCESSES REPEATED TEN MILLION TIMES because I want to say with this title that a living region, even a living village, can be created successfully only if many, many, many of the people in that society cooperate to make it happen—many individuals, acting in their own way, yet acting together.

For this to happen in different places of the Earth, for it to happen in the place where you live, it virtually requires that you, too, whoever you are, must play some role in it. So I want to suggest that you, no matter who you are, no matter what your work in daily life may be, if you have the inclination, choose to make yourself part of this process.

It is my hope that the transformation of the Earth, through millions of acts, will come from people acting individually and in small groups—from all of us, from all our hands, from yours and mine and the next person's—all over the world. This is not an empty expression of a romantic ideal. It is, in my view, unlikely that a living world can be created in any other way.

Please note: I do not say that the world which I depict OUGHT to exist. What I wish to say is something more fundamental than a moral lecture. I am simply describing, as matter-of-factly as I can, what kind of living world WILL follow from the widespread and repeated use of adaptive living process to unfold the world IF LIVING AND ADAPTIVE PROCESSES ARE REALLY USED.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

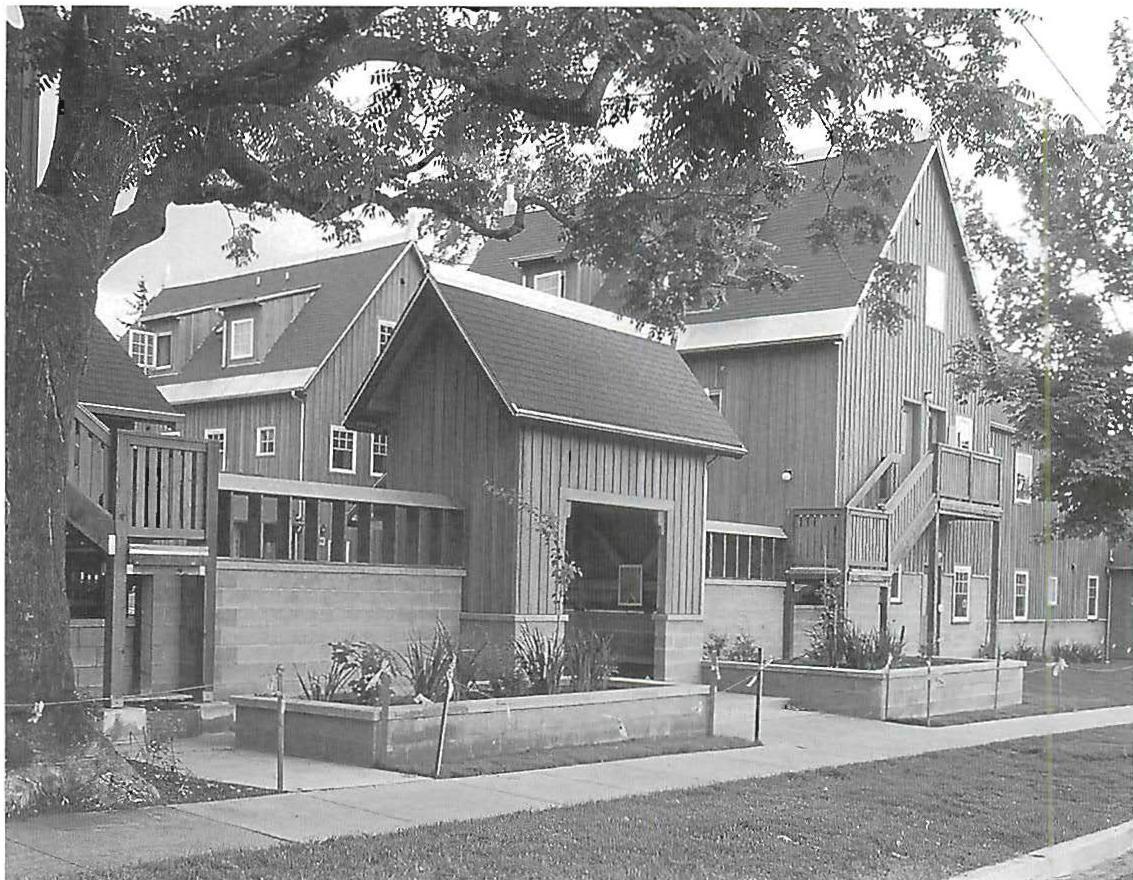

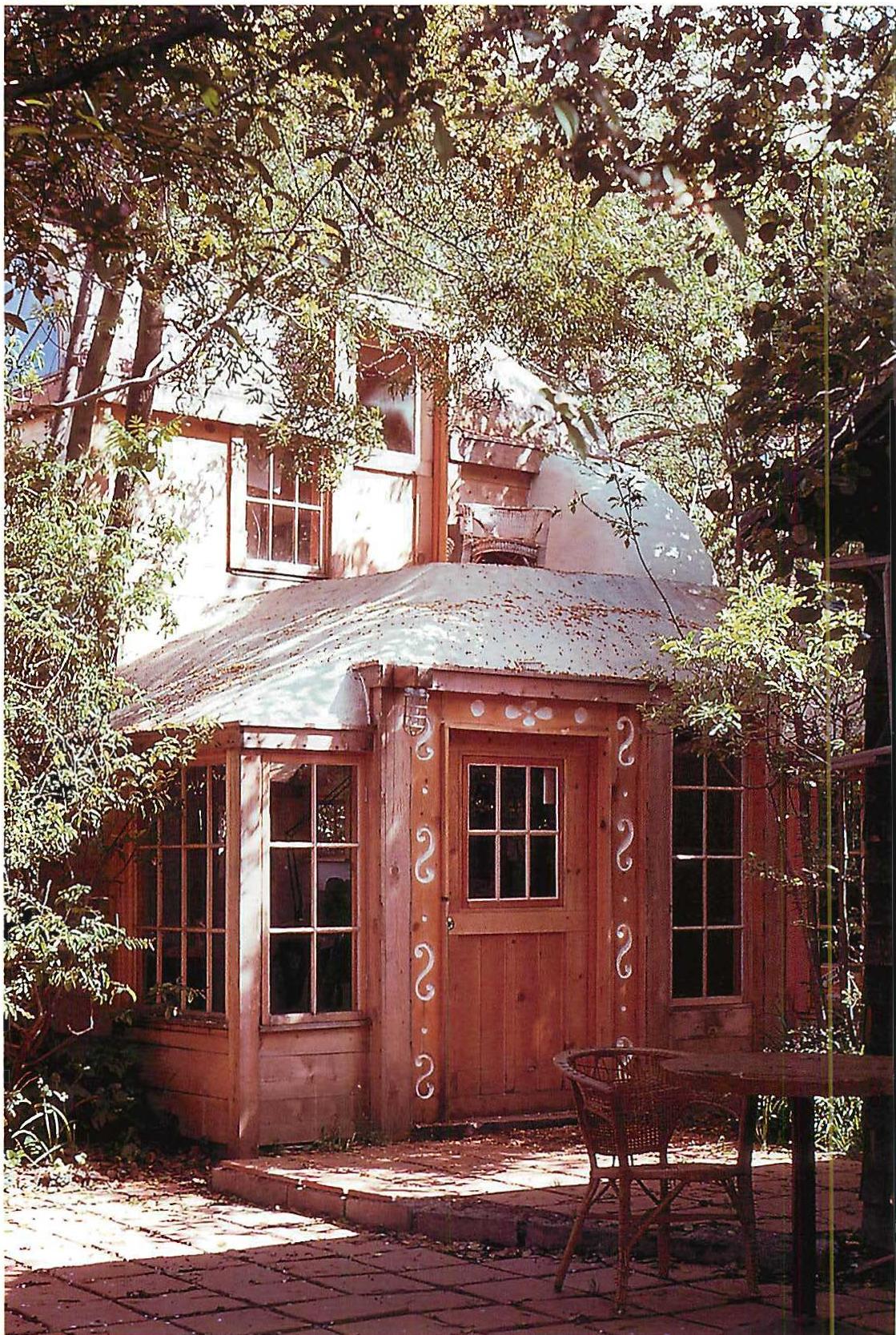

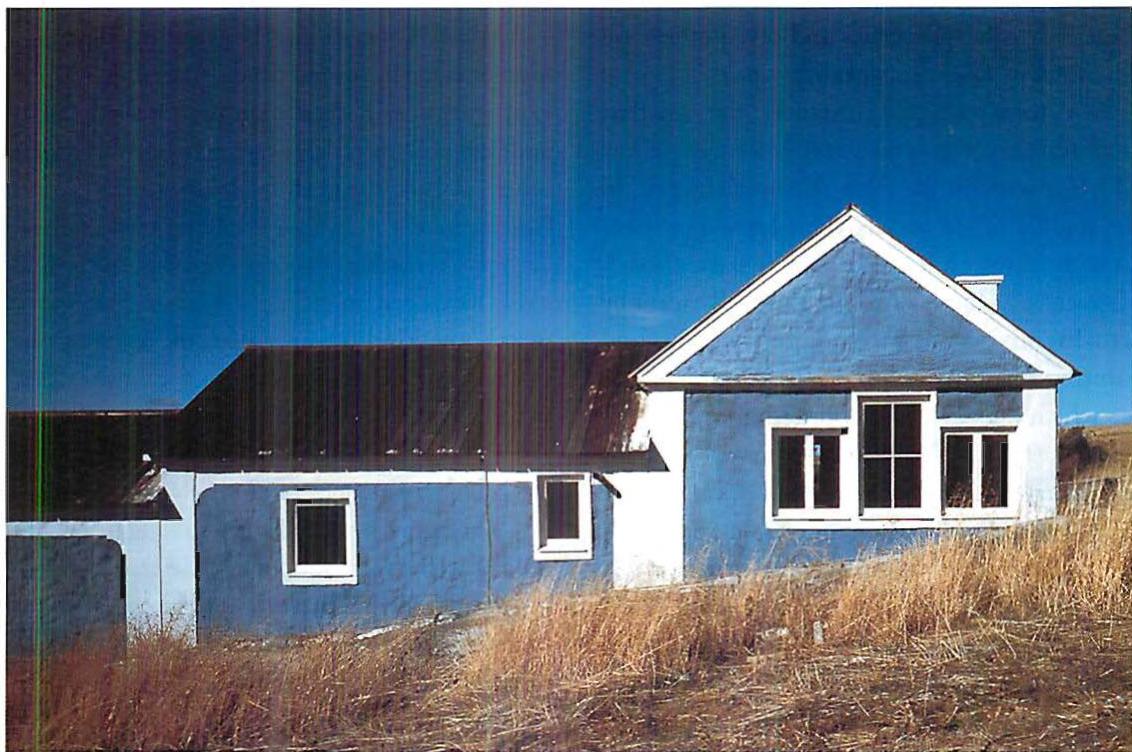

FRESHNESS AND DEEP ADAPTATION: THE CLASS OF LIVING BUILDINGS

What was lost in 20th-century building was the freshness of our buildings. Even when modern development tried as hard as it could to create life, the places built were often far too mechanical, so that the result became rigid, tired, and stiff—sometimes even horrible—and was often lacking, altogether, in the real freshness and sweetness that makes us joyful.

This problem, precisely, is the legacy we have inherited from the 20th century, and it is that problem, above all, which I try to solve in this third book. The solution of the problem, requires that we learn to distinguish two morphological classes, Class 1 and Class 2, that are defined on the opposite page. These have not previously been clearly distinguished. For it is not style that makes a building living or dead, but the freshness of its response to its surroundings; the truthful and spontaneous unfolding of order within its own fabric.

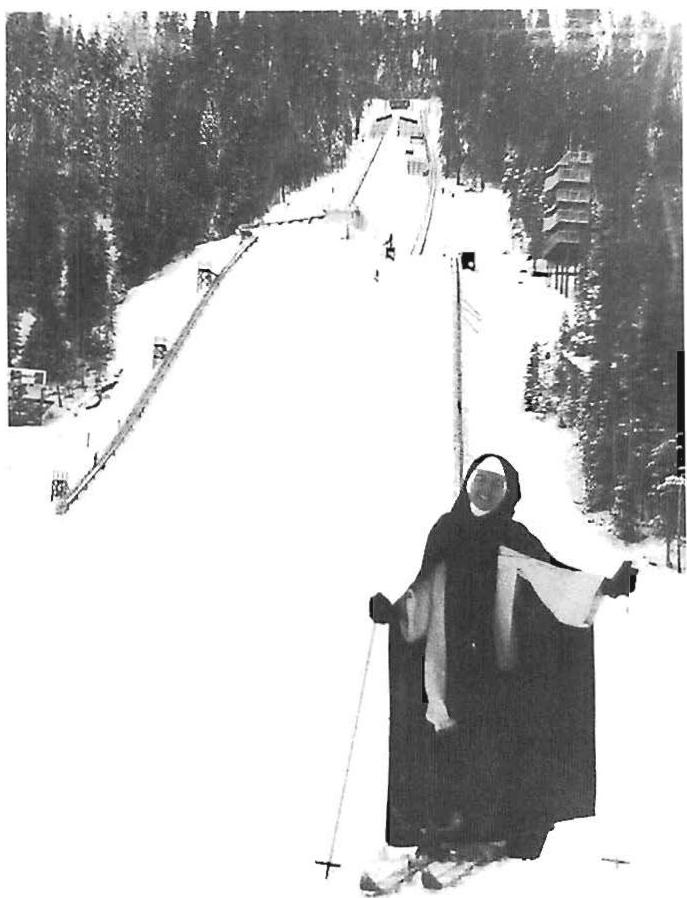

The freshness I refer to may be partly understood by reference to a martial arts discipline which lies far from the discipline of architecture. In Aikido, the martial art in which players fight, wrestle, and dance, it is above all the fluid response of one person's body to the configurations that the two players have reached together that is of the essence. What makes Aikido unique is that this response is non-mechanical, it is not within a system, rather it is always unique to circumstance. It grows out of the previous moment. That is what the players, dancers, fighters of Aikido learn. That, too, or something very much like it, is what makes a building fresh and alive and joyful.

Indeed, the essence of all life in any system at all, lies in the adaptive response of each new development in the system to the previously existing state. And this, too, stands as the foundation of any world where we experience true belonging. It cannot be achieved by a mechanical framework, by any mechanical system, nor by any stereotyped or stylistic response. Rather, it comes about only when the response of each act of building has been fresh, authentic, and autonomous, called into being by previous and present circumstance, shaped only by a detailed and living overall response to the whole.

Very few of the 20th-century architectural systems or procedures were able to approach this aim. Neither the prefabricated but supposedly endlessly open erector sets of the technical wizards, nor the humane procedures of community organizers can do it. Life is not only social but also, necessarily, geometrical. Life will come about only when each response is fresh, and each moment in the responding process truly builds something new and unexpected from a profound response to whatever whole existed just before. This, too, will be visible in the geometry, in the design.

The adaptive processes described in Book 2 (and used throughout this book as the underpinning of all adaptation) are uniquely able to achieve this quality. Similar sequences did achieve it in almost all traditional societies, and the buildings they created are living proof. Similar kinds of sequences can achieve it, now, in our modern and ultra-modern society, because the nature of these sequences is not to impose pre-fashioned order on things, but rather to extract what is new and fresh from the state of the world that exists.

That is the origin of the power of these sequences; that is their target; that is their goal.

And they do it in a surprising way. Although the adaptive sequences are highly ordered, and seem predefined, because they define steps and transformations in a disciplined sequence, it is the character of these sequences to help the user, the artist, the builder RESPOND to what is there, rather than to IMPOSE on what is there. This is the remarkable power of the structure-preserving sequences. It is this which helps people use such

AUTHOR'S NOTE

sequences to fashion true belonging—not fake belonging—for themselves.

Let me now make a key observation about deep adaptation or the lack of it, as distinguishing marks of the buildings we see around us in the world, and as the origin of the two classes I have mentioned.

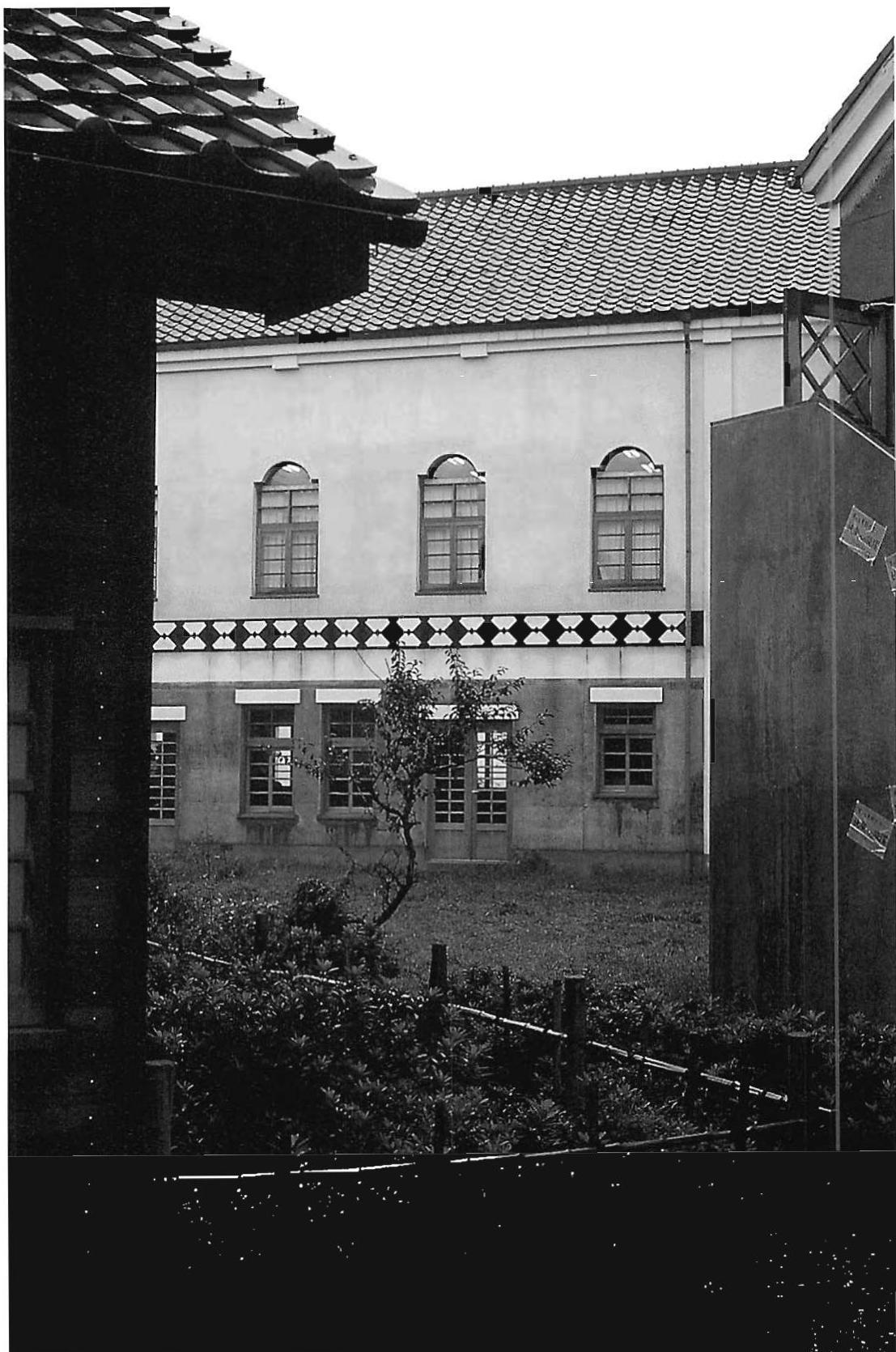

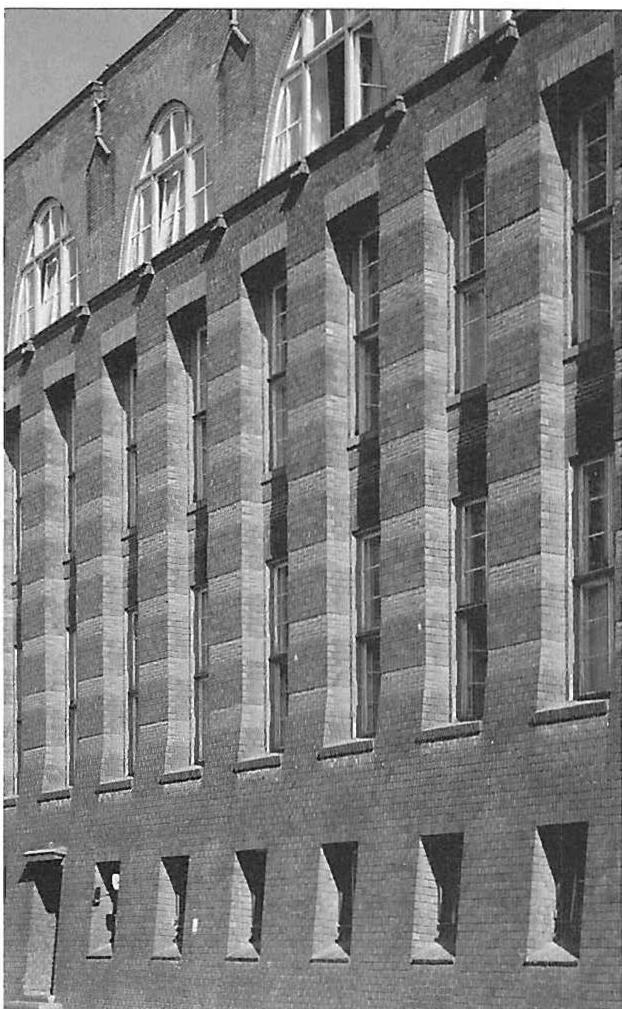

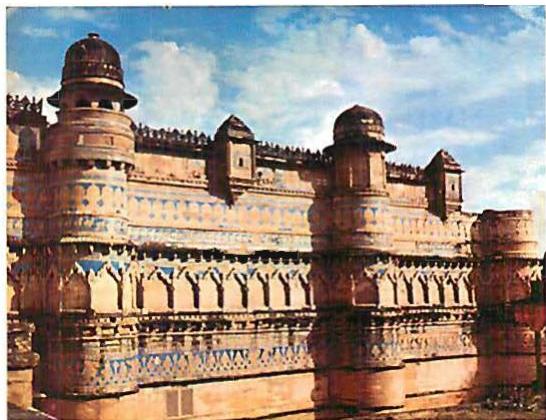

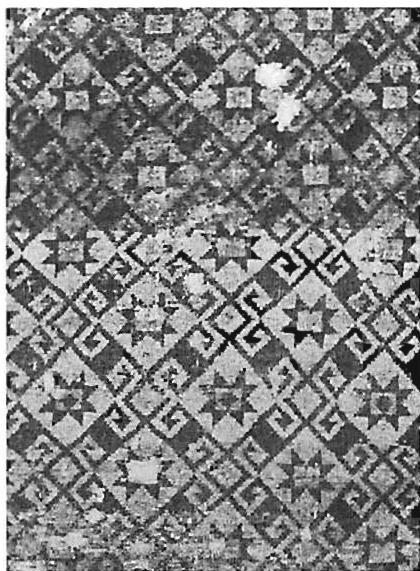

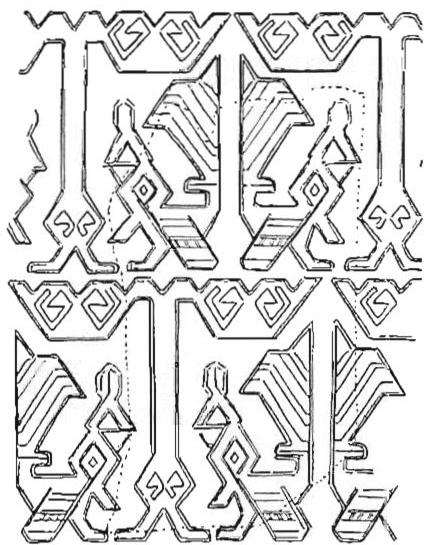

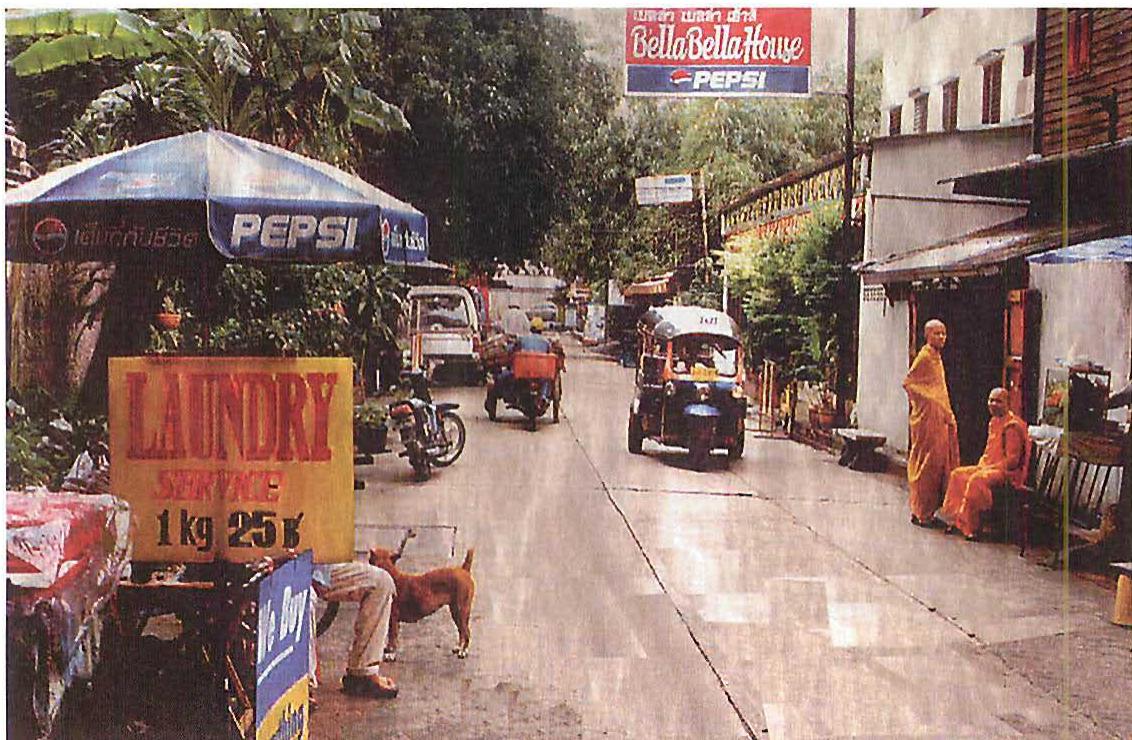

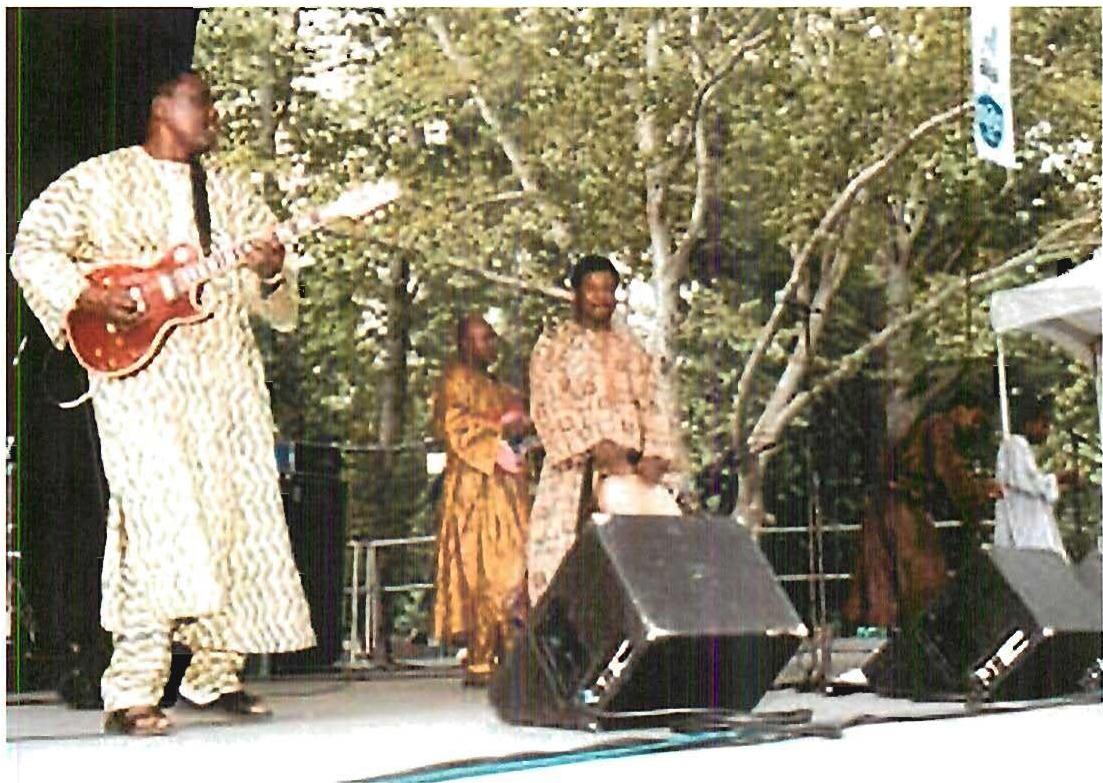

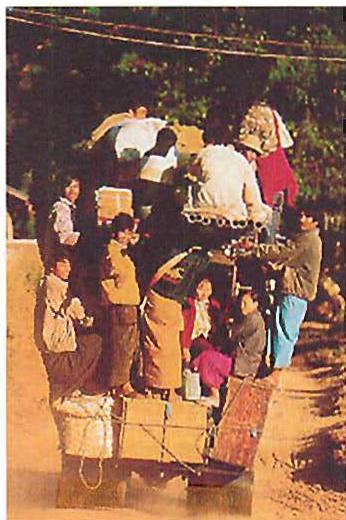

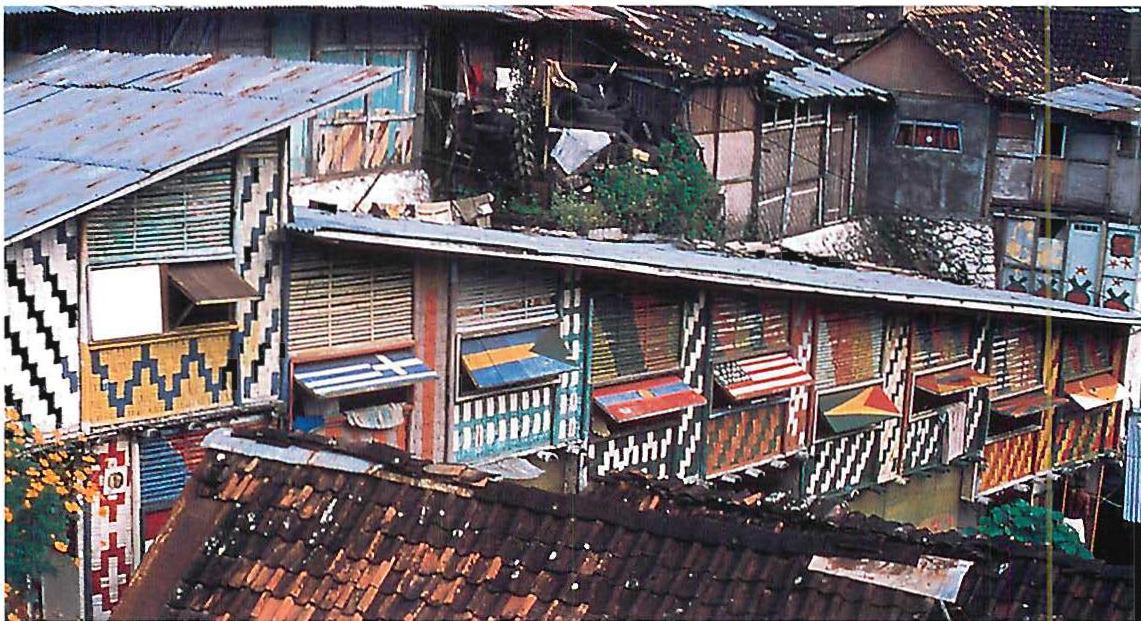

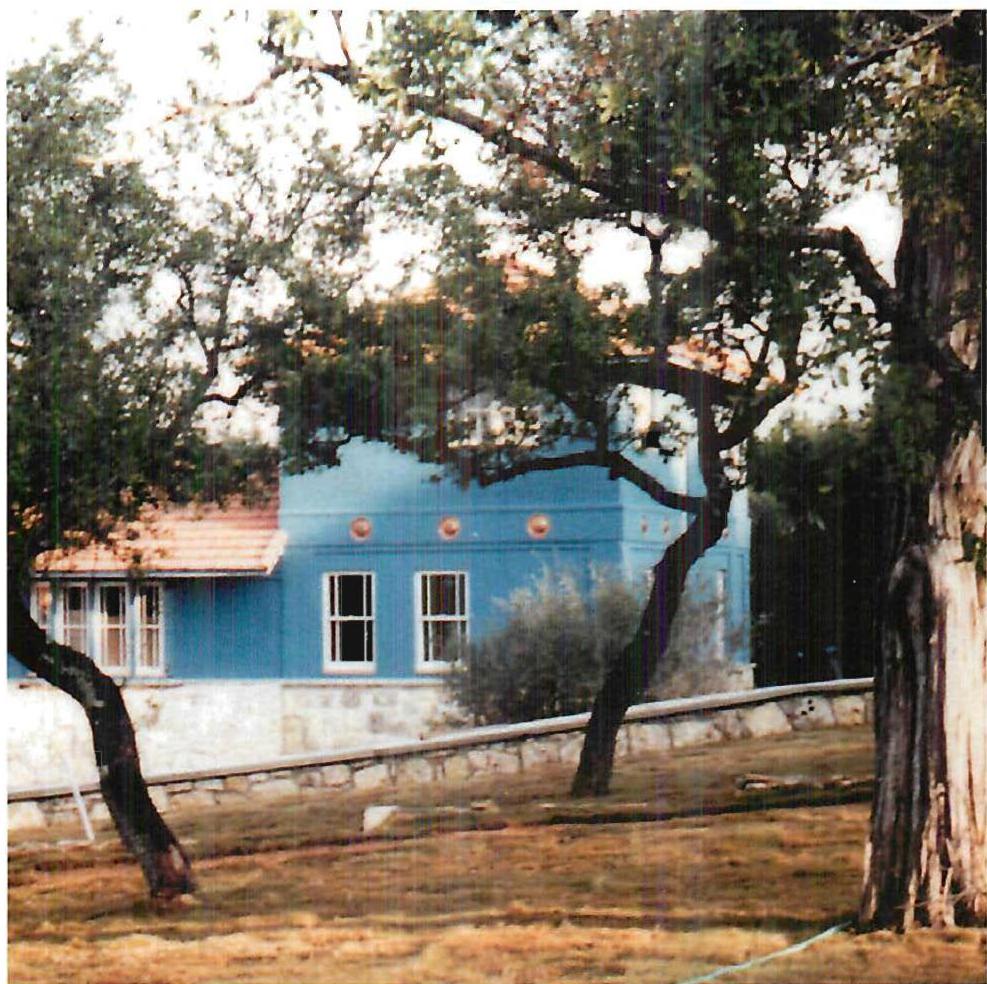

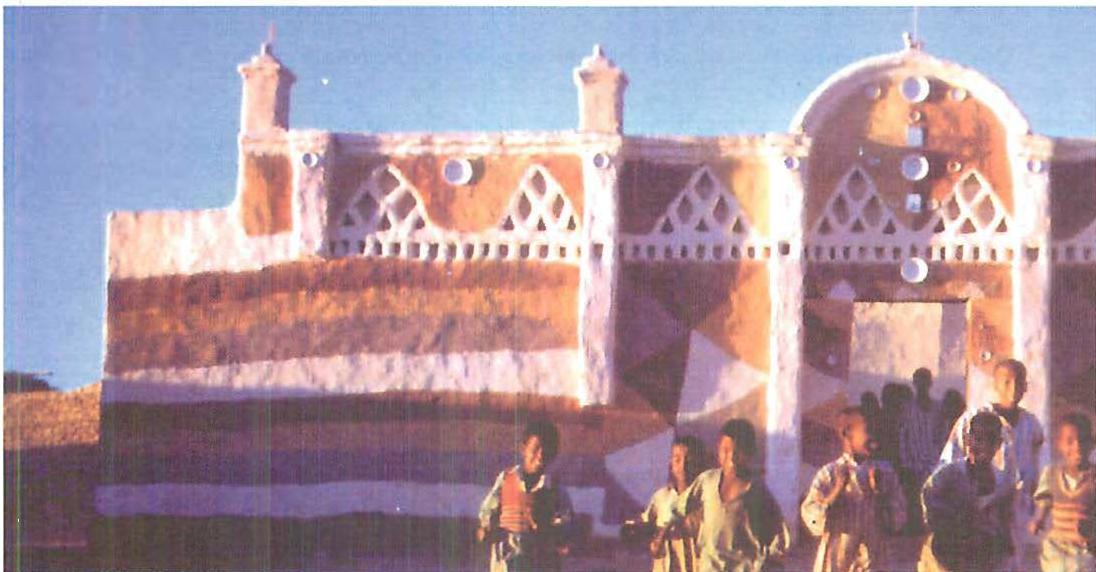

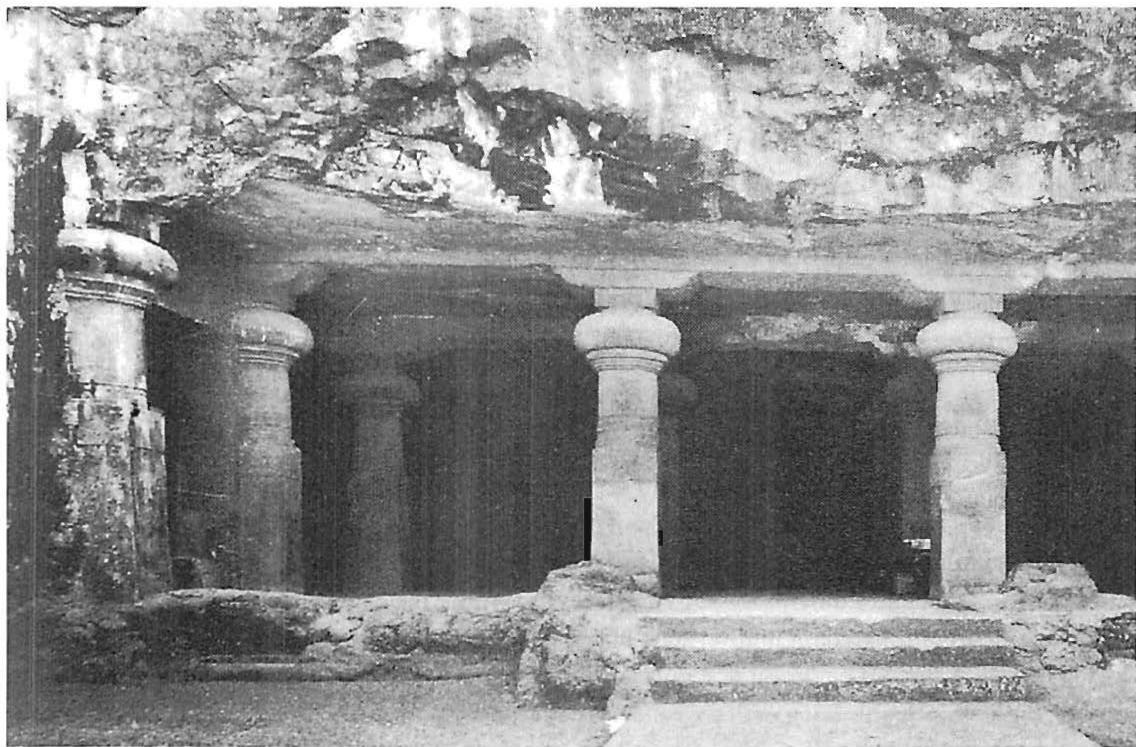

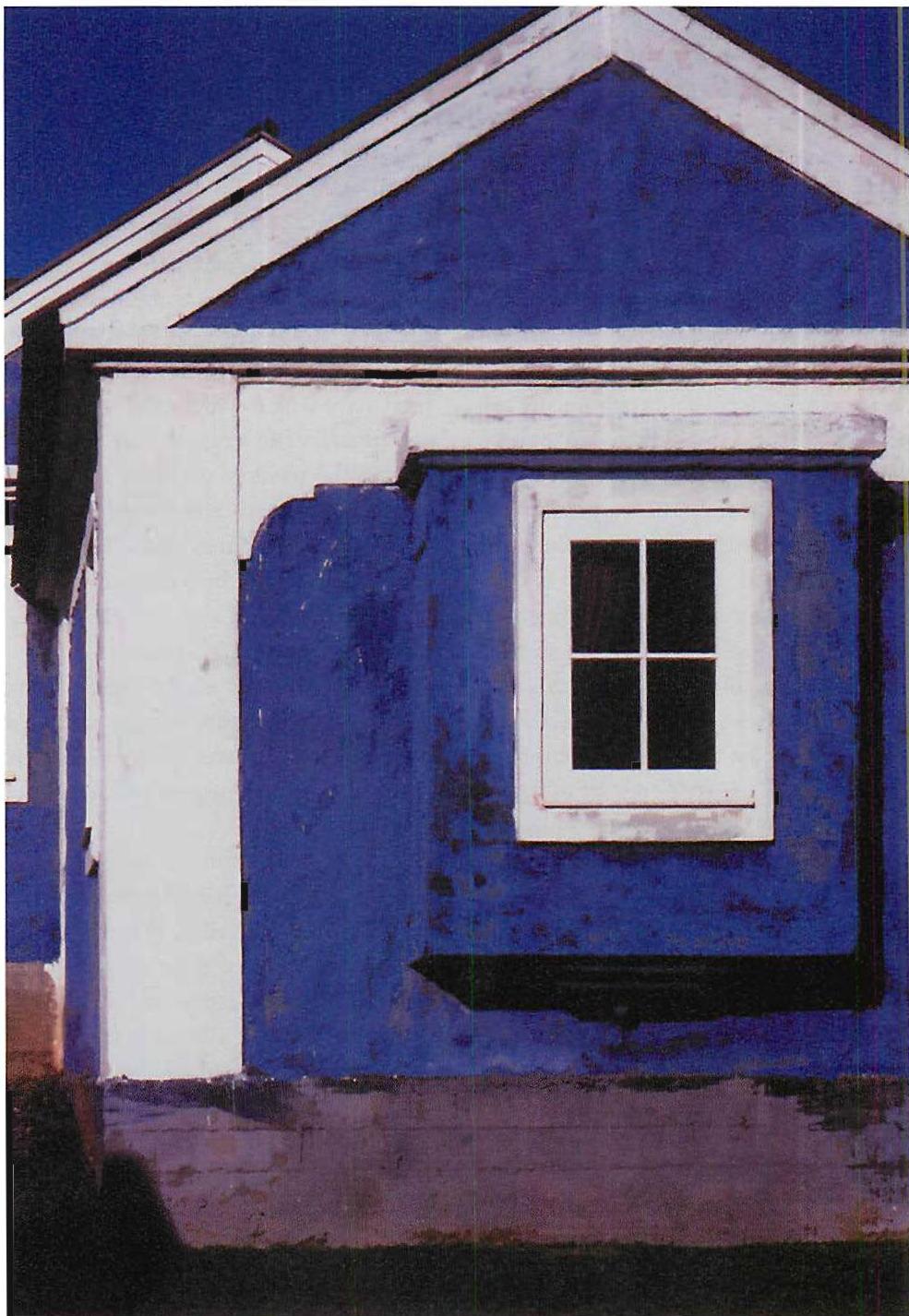

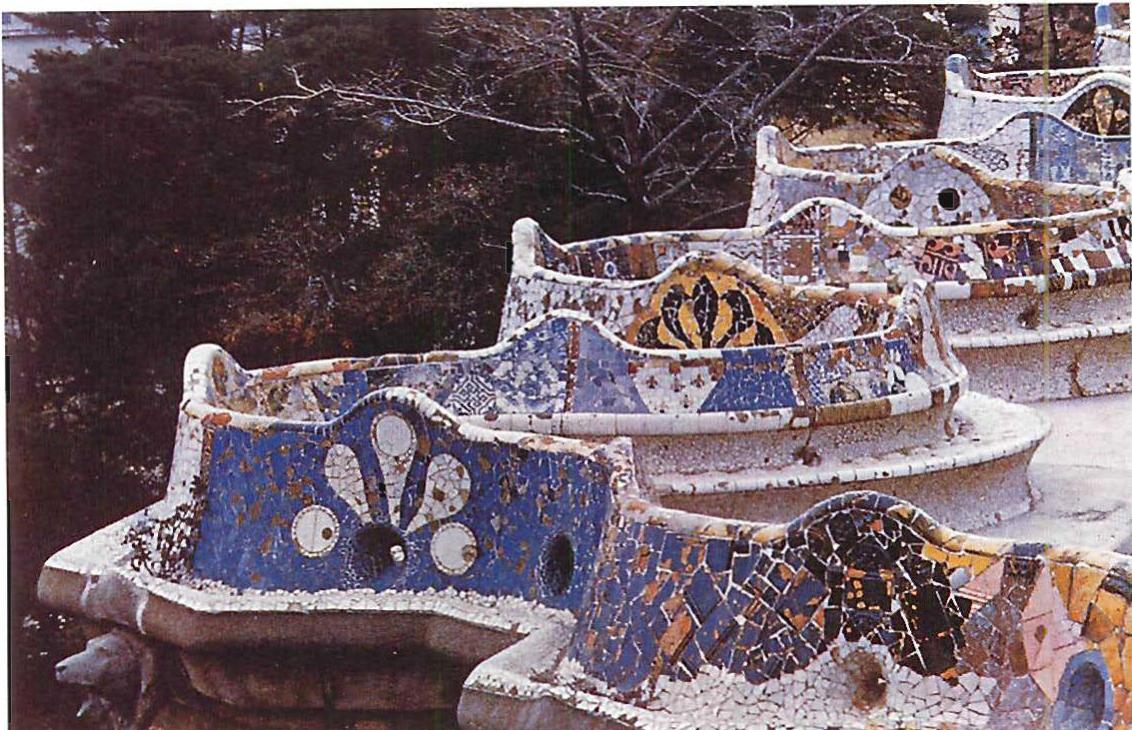

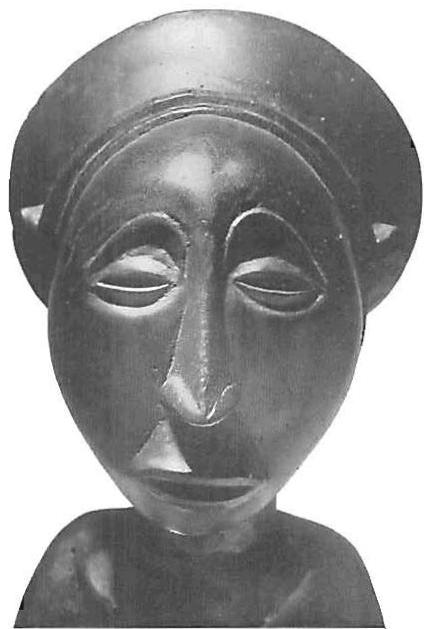

CLASS 1: THE CLASS OF BUILDINGS THAT ARE DEEPLY ADAPTED. If we consider all the examples of all traditional buildings, built, say, from the third millennium B.C. to sometime about 1900 A.D. (it varies from country to country and culture to culture), they are enormously different from one another. Igloos, African houses from Mali, Chinese palaces, the palace of Knossos, the villages of England, Japanese temples, Turkish cave dwellings ... Indian carvings... they are all enormously and vastly different from one another. They contain shapes, colors, roofs, attitudes, materials, of an unbelievable and rich variety. Yet somehow, too, they are all deeply similar. There is something about them all, which is the same.

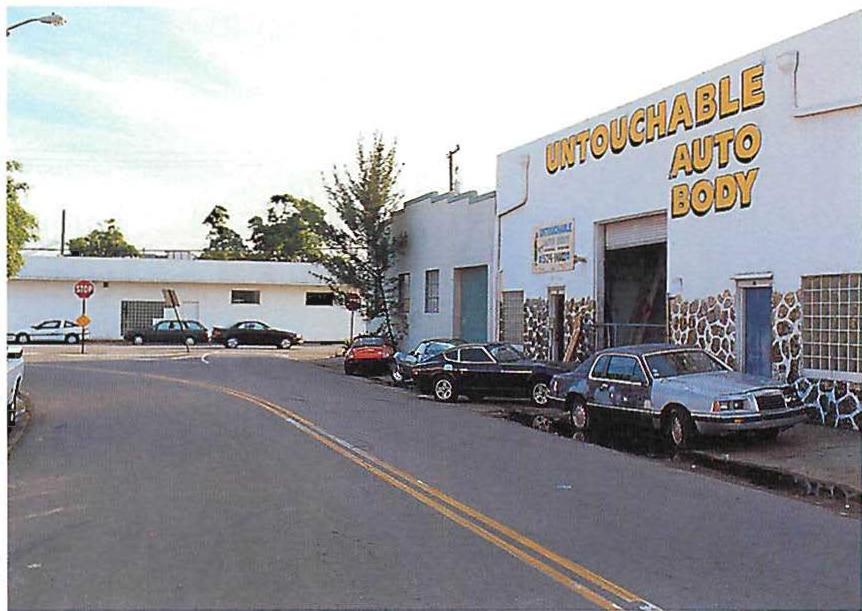

CLASS 2: THE CLASS OF BUILDINGS THAT ARE NOT DEEPLY ADAPTED. Now let us put together all the most widely published examples of the buildings of the recent historical era—say, from 1950 to 2000. These high-style examples also show many different shapes, materials, and intentions. They include, too, the fake traditional buildings made by contemporary methods of development. All these buildings, regardless of style, again, in some very deep way, all resemble each other. Once again, they share something deep which is the same in all of them.

The buildings in these two classes—those in Class 1 and those in Class 2—are utterly different, both in artistic substance and in morphological substance. This is fairly obvious. The important question is, What is the nature of the difference? On the face of it, it might appear that the distinction between the two classes is merely historical, referring merely to two eras of history—pre-1900 and post-1900. That observation though, for a scientist, would be far from

the mark. What the difference really has to do with, are two different expressions of the purpose and intent of architecture, two different sets of assumptions and procedures. The difference lies in the structure which results from the assumptions and procedures. The structure of the buildings in Class 1 and the structure of the buildings in Class 2 are quite different, not because of shape, or culture, or climate, but because of the deep, inner nature of their structure-generating assumptions, and specifically because of the way they deal, or do not deal, with adaptation.

What I mean by Class 1 is defined by one set of assumptions, relying on deep adaptation as the ordinary process of production. All the buildings in Class 1 share the deep mathematical structure of adaptation I have drawn attention to in Books 1 and 2 as living structure. It is the structure of those places and buildings which are adapted, deeply, to land and to people, and in which the inner parts of the buildings, down to the smallest elements, are also marked (and made) by continual, patient care and adaptation to the elements around it. The examples of Class 1 exhibit the structure that arises, necessarily, from this kind of adaptive unfolding. This is an invariant structure that may be understood in scientific terms.

What I mean by Class 2 is defined by another set of assumptions (outlined in Book 2, chapter 4). The buildings in Class 2 are not well-adapted structures. They represent a new brand of fantasy, so clearly marked that it is almost a commercial brand, glued on, somehow, to the products of our early first-stage industrial civilization, lacking the benefit of biological or social rigor, lacking the desire to satisfy the human heart, not stemming from the inner voice of ordinary people, but stemming instead (very often) from the ego-hungry voices of architects who desire to be famous—and who wish to promote a product. In other cases similar buildings may be generated by the wrong kinds of mass production, or by crude over-technical processes that are cut off from all possibility of detailed fine adaptation.

The fact that the buildings shown on the following 700 pages resemble buildings in Class

1, and not the buildings in Class 2, is inevitable. It occurs because the buildings shown in this third book come from living processes—that is, from processes and procedures which allow adaptation and which generate, in one form or another, precisely that living structure which these four books are about. They do not resemble the buildings of Class 2, because Class 2—its motives, intentions, images and geometry, and above all its geometric generating system—have nothing essential to do with human life, or with the life of animals or plants.

At present, the architectural images of 1950-2000 have so strongly brainwashed the public, that a person could be forgiven for asking of the buildings in this book, “Why don’t they look ‘modern’?” But the truth is, most of the buildings in Class 2 are not modern in any practical sense at all. They are merely mannered, and infected by a lack of responsibility for the connection of buildings to land and people.

Thus there is an inescapable appearance of the result. The buildings which come from adaptation—continuous, patient adaptation, concern with wholeness and nothing else—have a certain discernible structure. That is because adaptation goes towards certain structural features in a building. The buildings which have these features are not modern, or ancient, or historical: they just happen to form a definable mathematical class (see pages 685-91), and specifically, a definable class of forms (see pages 639-76). This class includes very few of the buildings being praised in our time. That does not mean the products I shall show you are nostalgic or sentimental. It means simply, that, if we have to find our way toward that large class of deeply-adapted structures, we shall find our way towards a new set of buildings and building types. The fact that they vaguely resemble members of the huge class of all buildings built all over the world during a five-thousand year period occurs, not because I desire to imitate them, but simply because for 5000 years those buildings were most often members of just that class which

is reached by careful internal and external adaptation—what I, too, have tried to do—while the buildings of the last fifty years were most often not. That’s all there is to it.

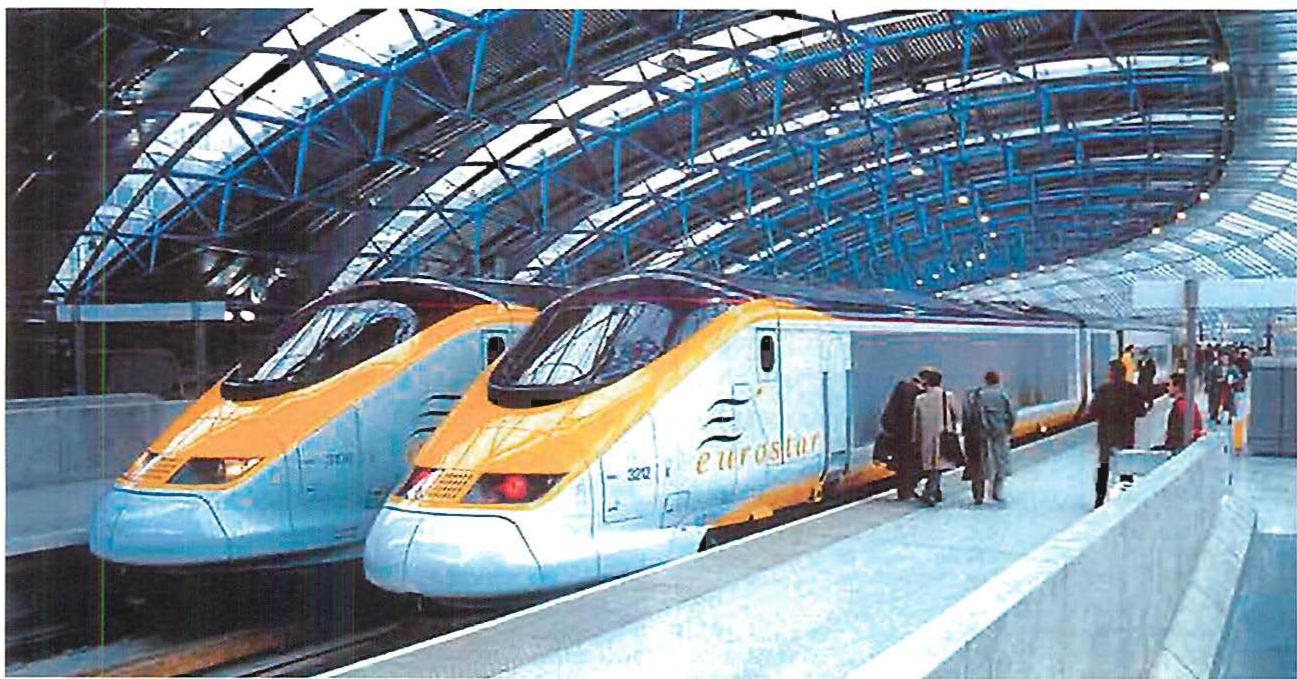

There is no inherent reason why buildings of our era should not be deeply adapted, and should not therefore be Class 1 buildings in their geometric structure. There is no reason, either, why many of them should not be made of ultra-high-tech materials. What matters is their ability to contain and exhibit the intricate deep structure of an adaptively made thing. The Eurostar terminal in London (page 119), or Calatrava’s building in Milwaukee (page 195) are examples which happen to use recently invented materials. They are therefore useful as lessons—since both exhibit some of the qualities of an adapted thing. It is my hope, that many of the Class 1 buildings in this book will provide a model for architects and builders and artists, indeed for all people, who wish to come to terms with the life of the planet, and who view themselves as people whose most pressing undertaking is to maintain the beauty of the Earth.

It is strange that in the recent era of machine society, when we encountered beauty—a living structure—and it aroused deep feeling in us, we often dismissed what we encountered as “only a feeling” and therefore not very important. In fact, the presence or absence of deep feeling, is yet another way we may distinguish between buildings of Class 1 and buildings of Class 2. Buildings of Class 2 generally do not evoke deep feeling. Buildings of Class 1 generally do evoke deep feeling. The difference comes from the different adaptive structures that they have. In this regard, Class 1 buildings are like works of nature—a patch of bluebells in a wood, for instance, or mist in the mountains. There, too, the feeling evoked arises because of the structure of the natural phenomenon, and because of the adaptive process by which it is made. Deep feeling appears in these buildings, as it does in nature, because they emerge through subtle adaptation from the whole, and because at each stage of their unfolding they support the whole.

The first two chapters contain discussion of what is perhaps the most important human issue in the built environment: our sense of ownership, participation, and belonging to the world.

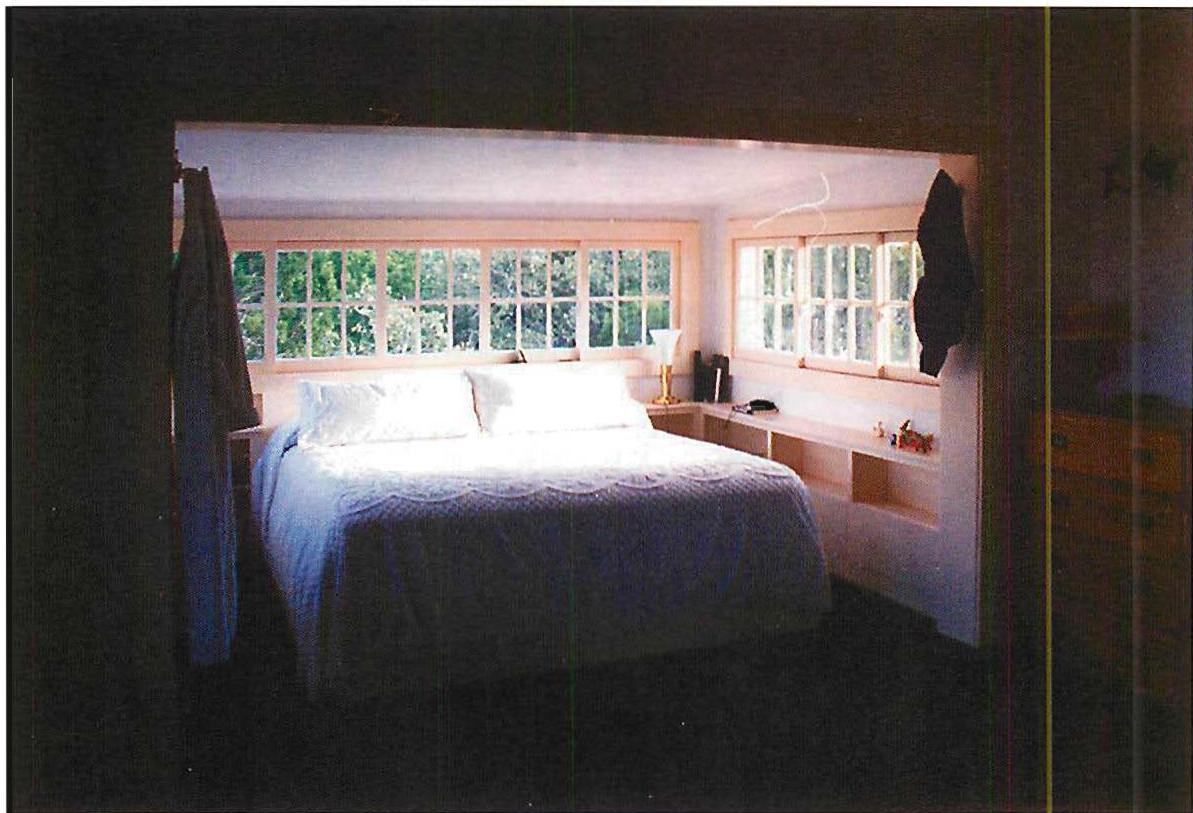

Chapter 1, BELONGING AND NOT-BELONGING, suggests that our belonging to the world works in two ways: the belonging that we feel in public places and the belonging which we feel in individual, private, places. In a world where living processes are working properly, each individual private place (whether private house, apartment, office, workplace, or workshop) will have its own uniqueness that allows its users to belong to it. At the same time, to work well each of these private places are directly attached to some hull of public space, thus giving us — people — participation in the social world at large.

Chapter 2, OUR BELONGING TO THE WORLD, describes with small examples, and with more intensity, just what I mean by belonging. This belonging — the relation through which we human beings are connected to the Earth — a visceral feeling of joy — hinges on the sensation that we have the right to be here, that we belong to the world and it belongs to us.

Only living process can generate belonging. When living processes are working well, our belonging comes about naturally. Then, both in public and in private, our belonging to the Earth is established without effort.

CHAPTER ONE: BELONGING AND NOT-BELONGING

The single photograph on the next two pages describes, vividly, the loss of belonging which has become commonplace in our era. It is a picture of people in Prague, November 1989, receiving the news that the Berlin Wall had come down. The haunted faces of the 20th century. Are these people glad about the onset of "democracy?" Is there a glimmer of hope in their mysterious faces? Or are they simply fearful because they now face the prospect of a money-centered world? I believe it made little difference to them. Belonging, as I have described it, was not available to them in either case. Because of that, like many of us whose belonging is not clear, they are afraid. That, in my mind, is what is written on their faces in this photograph. And we — who ALSO face this, every single day — what are we to do about it?

The haunted faces of the 20th century. Are these people glad about the onset of "democracy?" Is there a glimmer of hope in their mysterious faces? Or are they simply fearful because they now face the prospect of a money-centered world? I believe it made little difference to them. Belonging, as I have described it, was not available to them in either case. That, in my mind, is what is written on their faces in this photograph.

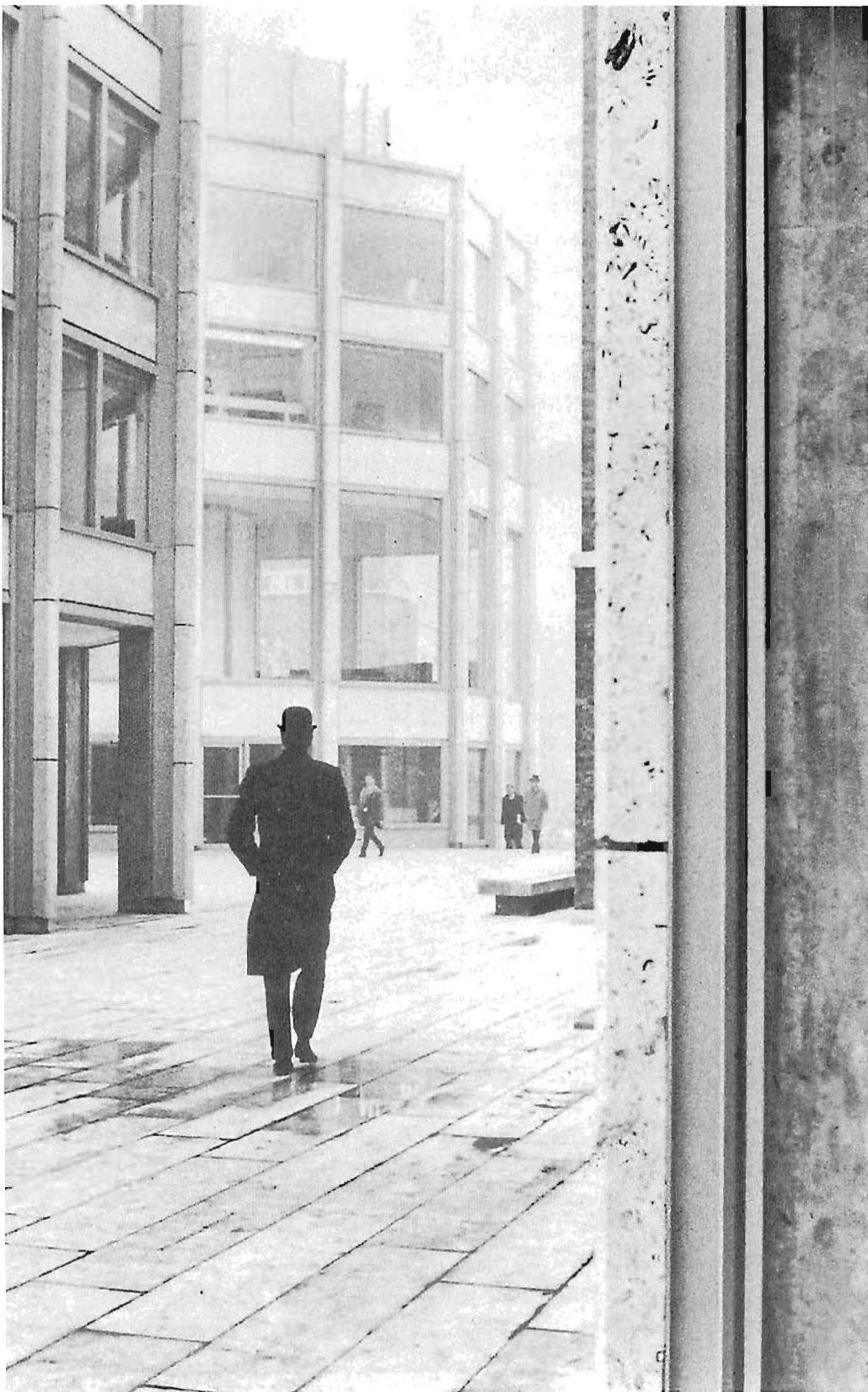

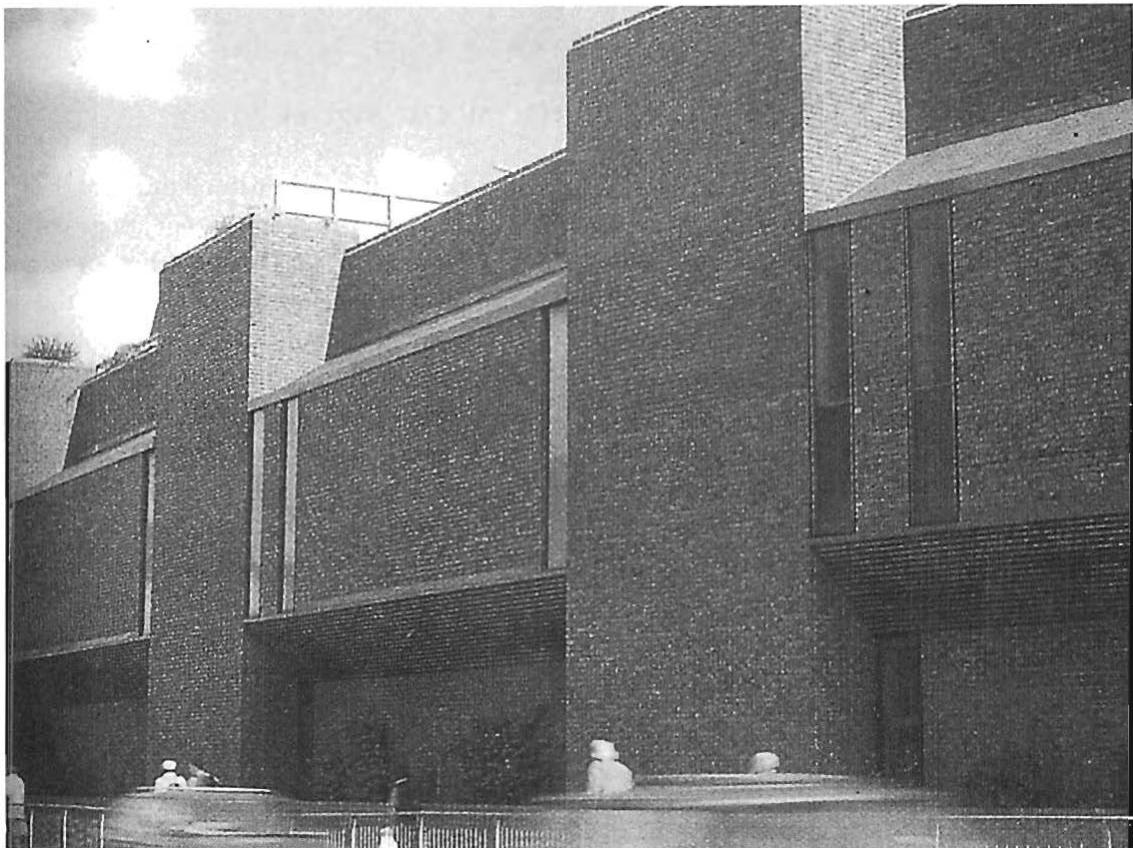

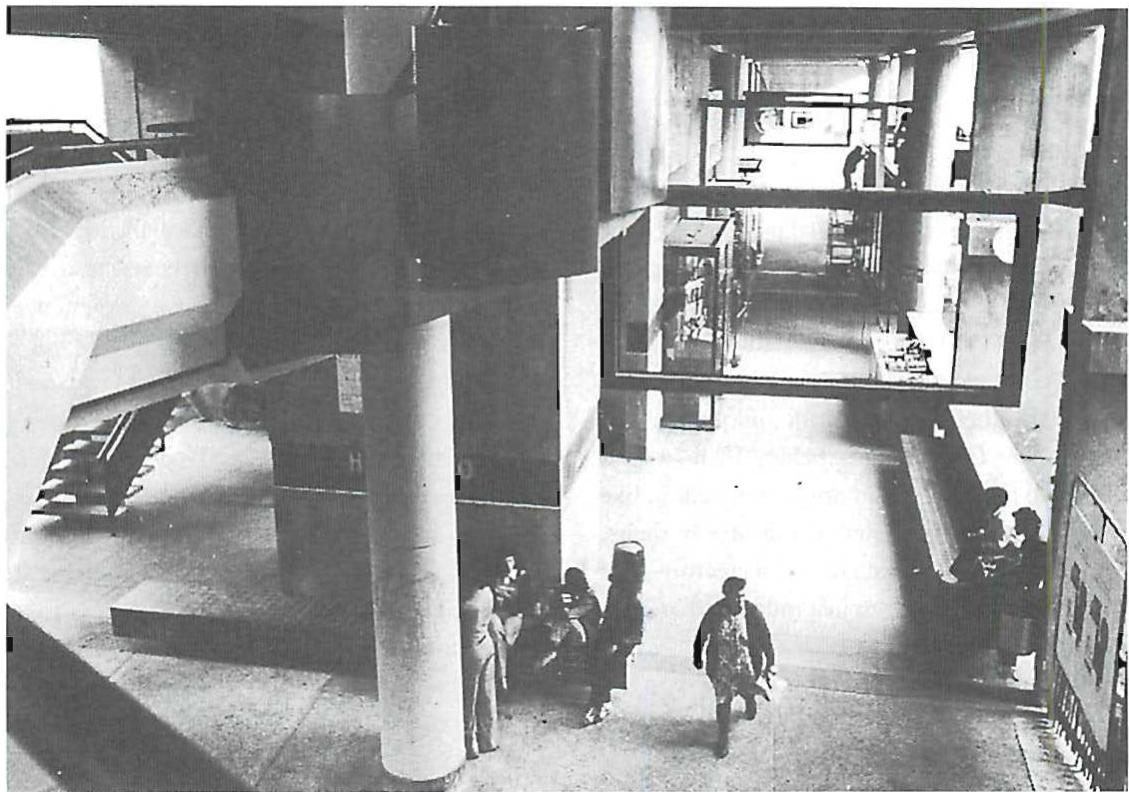

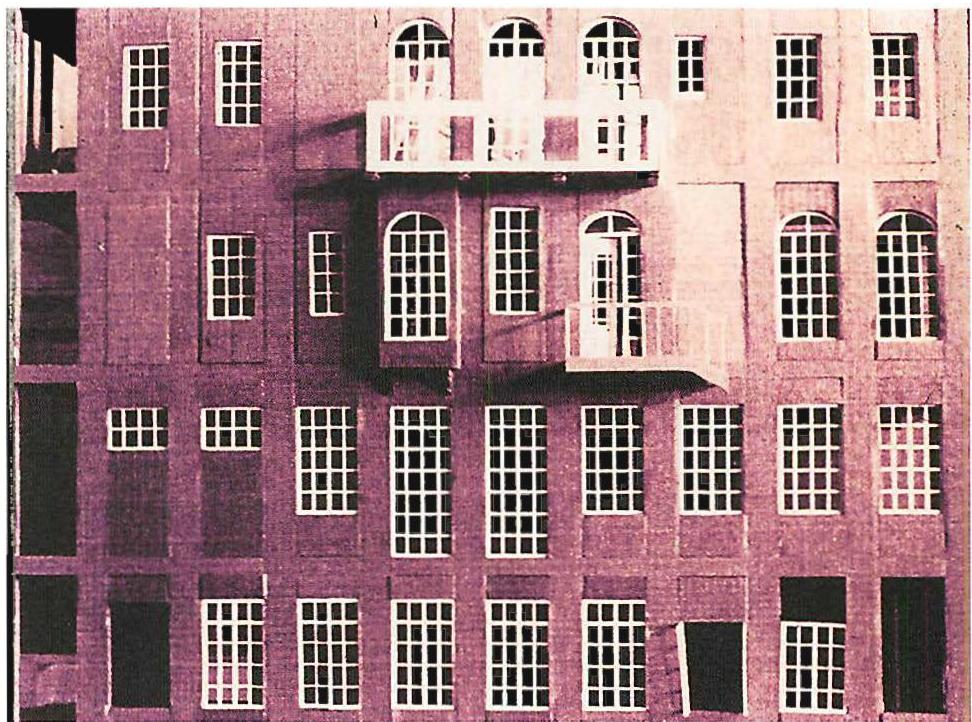

NOT BELONGING: The cold landscape of much late-20th-century city construction. It seems well-designed, but is alien to any feeling of belonging to the Earth. The photograph shows the Economist office building in central London, built about 1980.

1 / WHO, TODAY, CAN TRULY ENJOY BELONGING TO THE EARTH?

How many human beings alive today can truly enjoy belonging to the Earth?

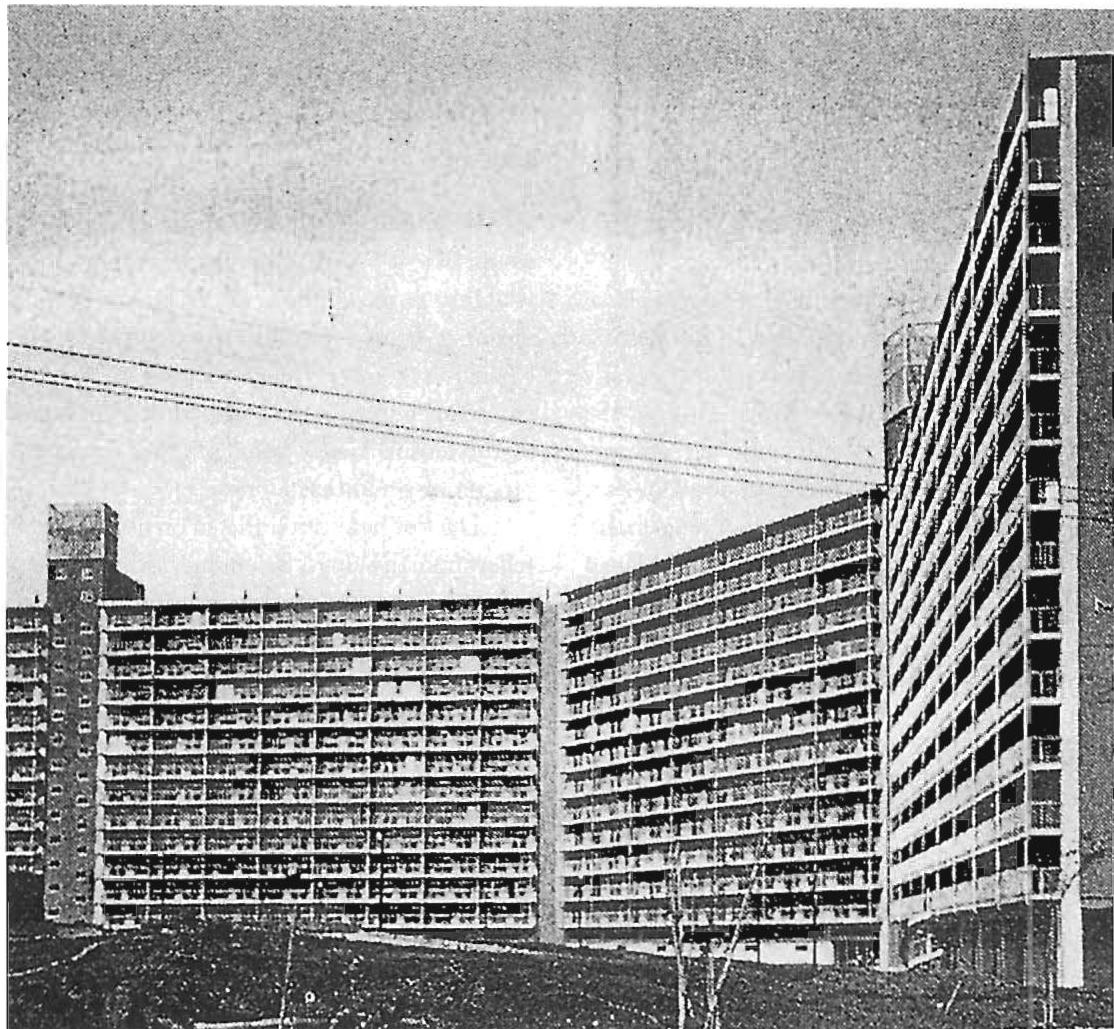

There are about 6,000,000,000 people on Earth. The conditions they live in are getting worse. Though many live in poverty, the prevailing model of existence for them — at least the present ideal which people and their governments strive for — is the model of development, mass housing, condominiums, shopping malls, worker housing in Poland and China and Japan and America. It is the quality of this mass housing, mass office space, mass hotel space, mass retail space — in short, the mass cities created by the builders of these neighborhoods and projects — which we must above all reconsider.

In these cities it is the simple human right of belonging, above all, that I want you to think about and pay attention to.

In chapter 2, I shall discuss belonging as an emotional fact of life, as a necessity. And I shall say something about the way it works. But I would like, if I can, in this chapter first to shock you into a recognition of the truly dreadful meaning of my pleasant-sounding words about belonging — and persuade you that much of the emotional misery of the 20th century was caused by the terrible loss of belonging our contemporary processes inflicted on society.

The loss has been inflicted on us and on our fellow human beings. Belonging, although it was common in traditional towns and villages, is missing in far too much of modern society. The forms of environment we have learned to create in modern times have caused us to lose the sense of true connection to ourselves and our society. That has happened, in large part, because of the nature of space we have created. It has happened because the public space of our present-day cities, both legally and metaphorically, no longer belongs to us to any deep extent. So, of course,

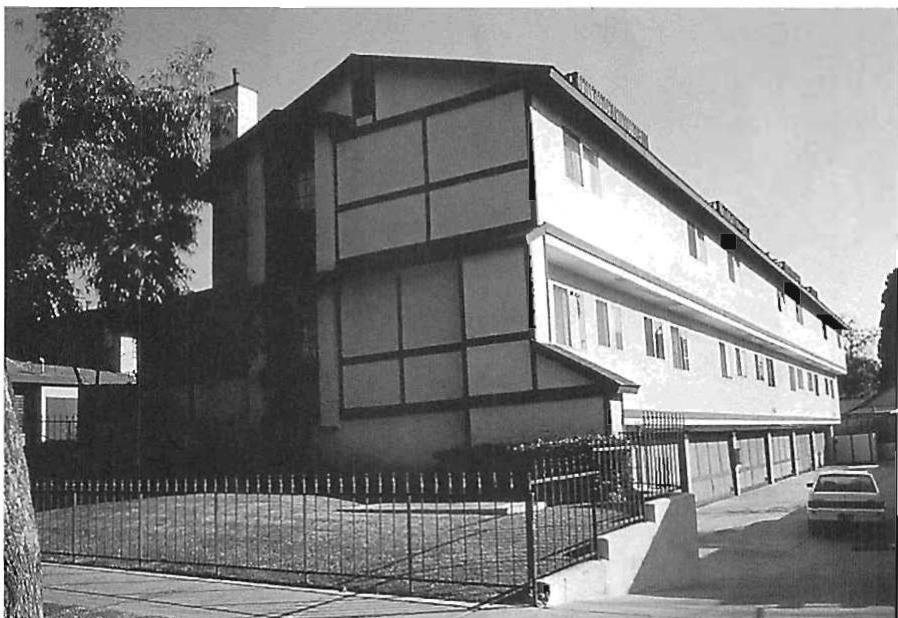

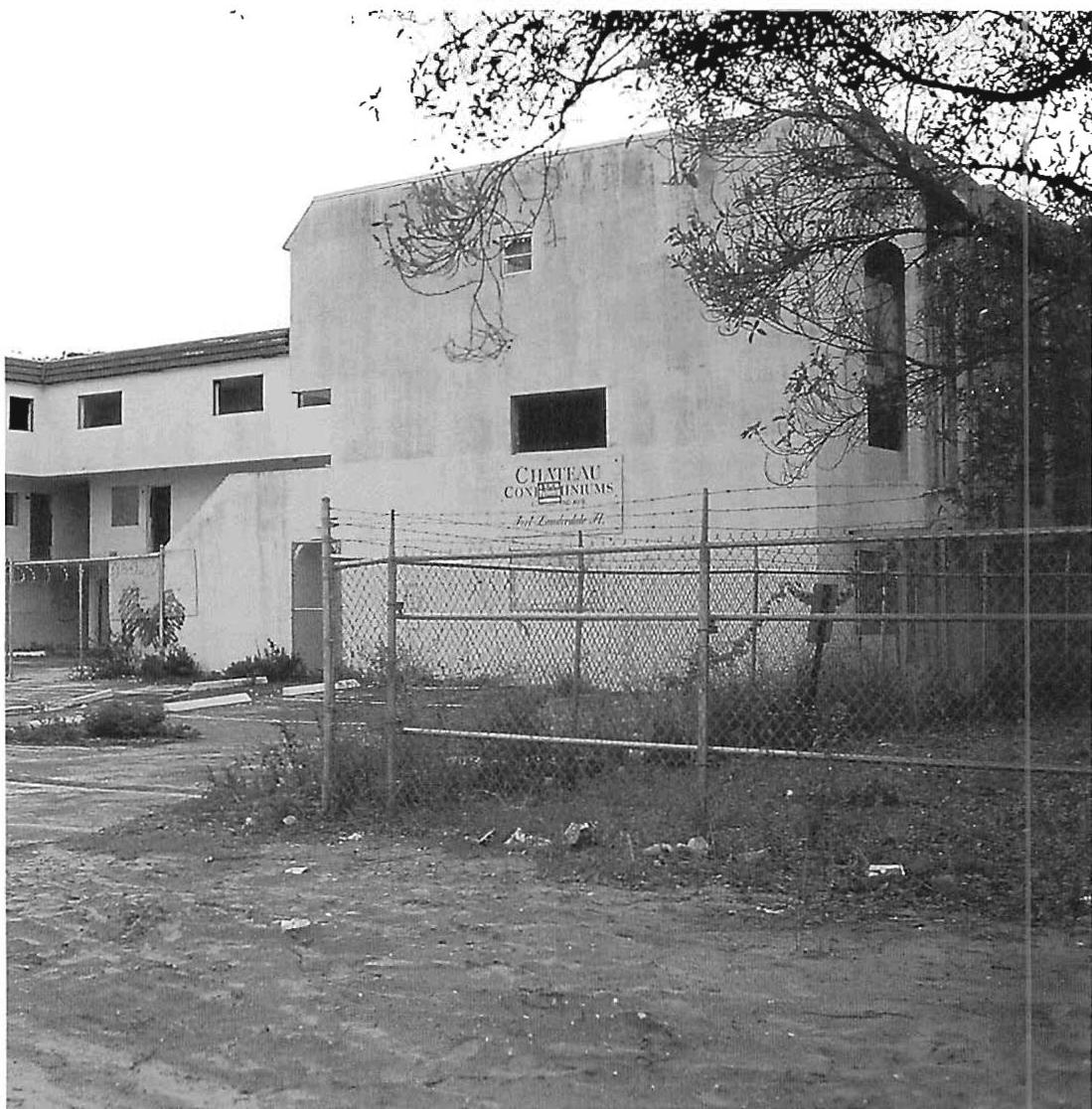

NOT BELONGING: A building in Oakland, California, horrible, but dressed up by the postmodern developer architecture of the 1990's to seem sympathetic. It is just as alienating and unable to support a true sense of belonging as the building in the picture on page 30, only dressed up to seem better. A wolf in sheep's clothing! Our prevailing thought, whenever we see a building like this: "Oh my God, they are doing it here, too, and there is nothing I can do about it."

we are not entirely well there since it does not belong to us. That must be dealt with. And the private spaces, individual places, too, are most often not particular to different individuals, and do not support belonging. One of the most frightening aspects of the 20th-century city was its faceless, nameless character. We saw identical apartments, identical offices, identical apartment windows, identical columns, identical bricks. The individual was hardly visible. Cities today do not reflect the idiosyncracies and human characters of people. They do not reflect the multitudes of differences which are the source of our humanity.

I have finally become convinced, after thinking and working for forty years, that

living processes are absolutely necessary in buildings and in towns and in the countryside simply to create belonging, true belonging. Belonging cannot, in my view, be created by non-living process.

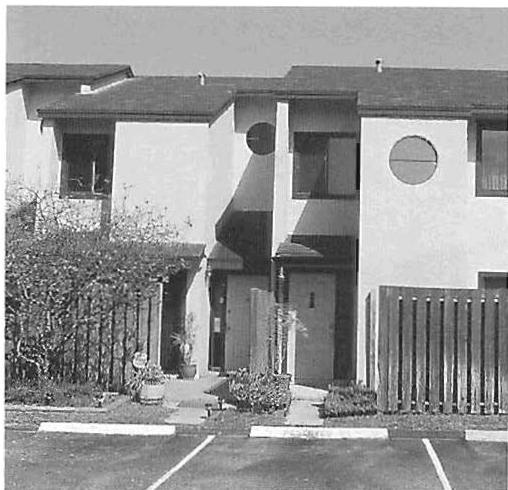

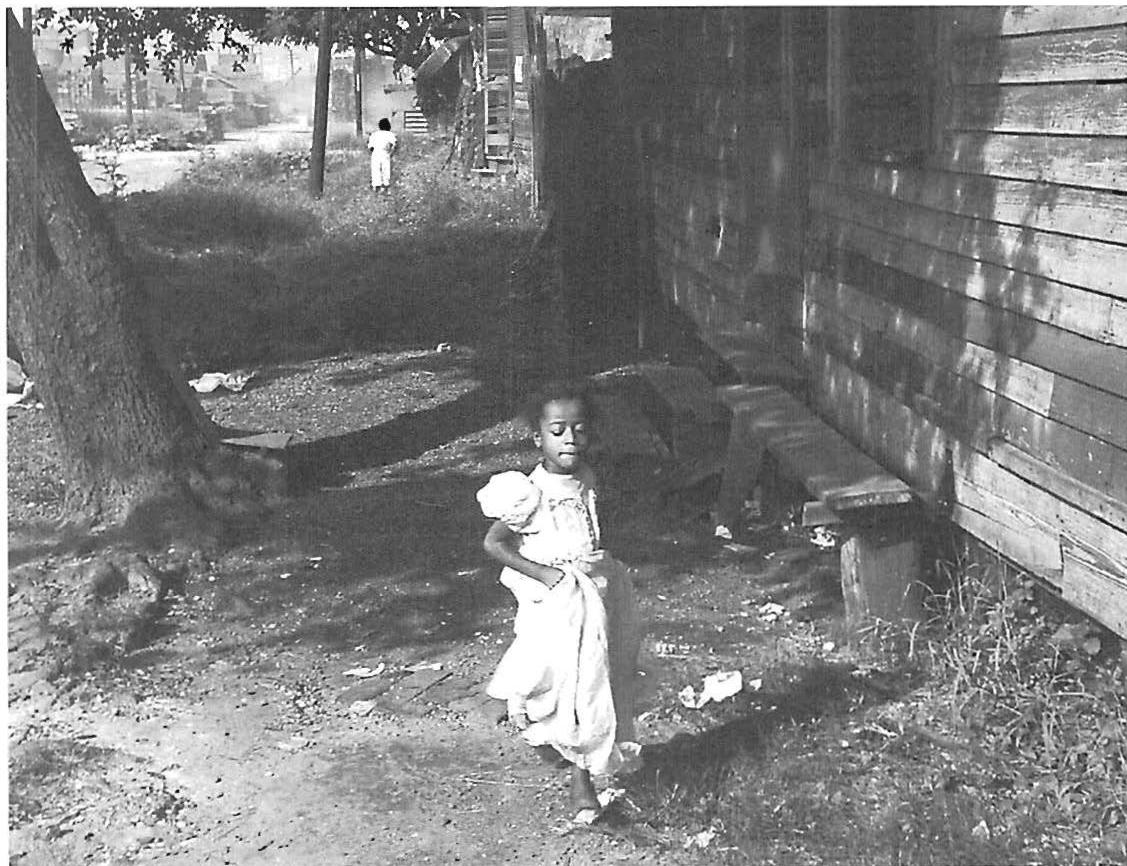

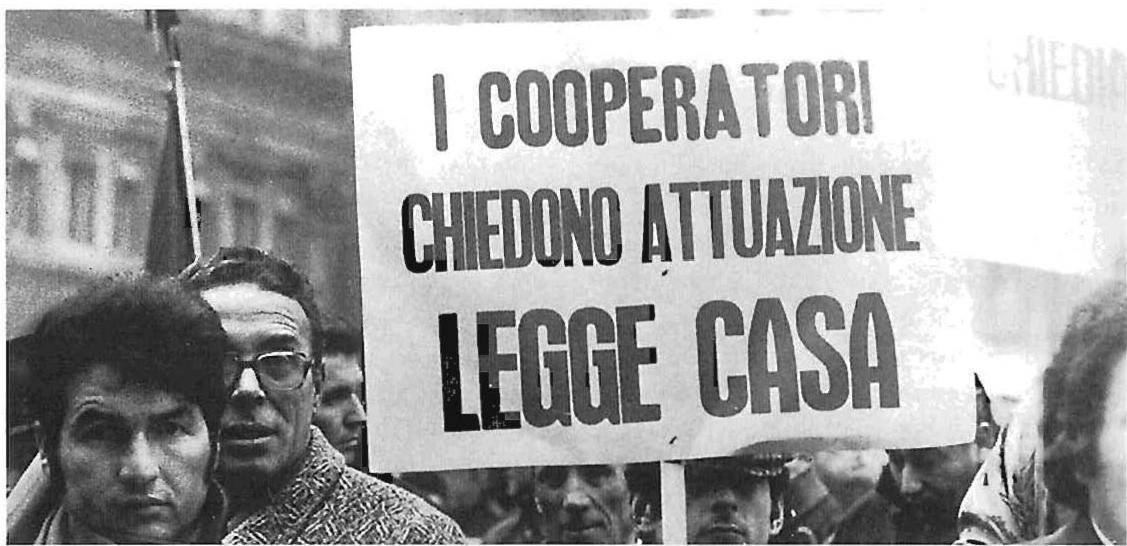

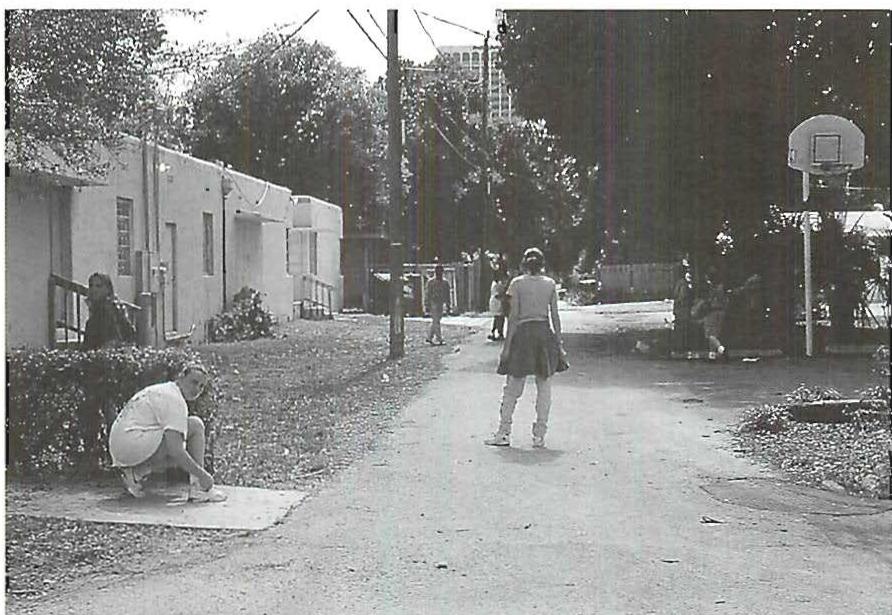

In the photographs on these two pages, we see some of the more horrible images of the 20th century. They come from a development process very far from the unfolding process. They do not reflect a living process, but a brutalized process. In almost no detail they contain do they reflect the fundamental process. Because they cannot create uniquely adapted centers, and cannot create "inhabited," "lived-in," positive space, they bespeak the character of not-belonging. That is the anonymous quality our age has created.

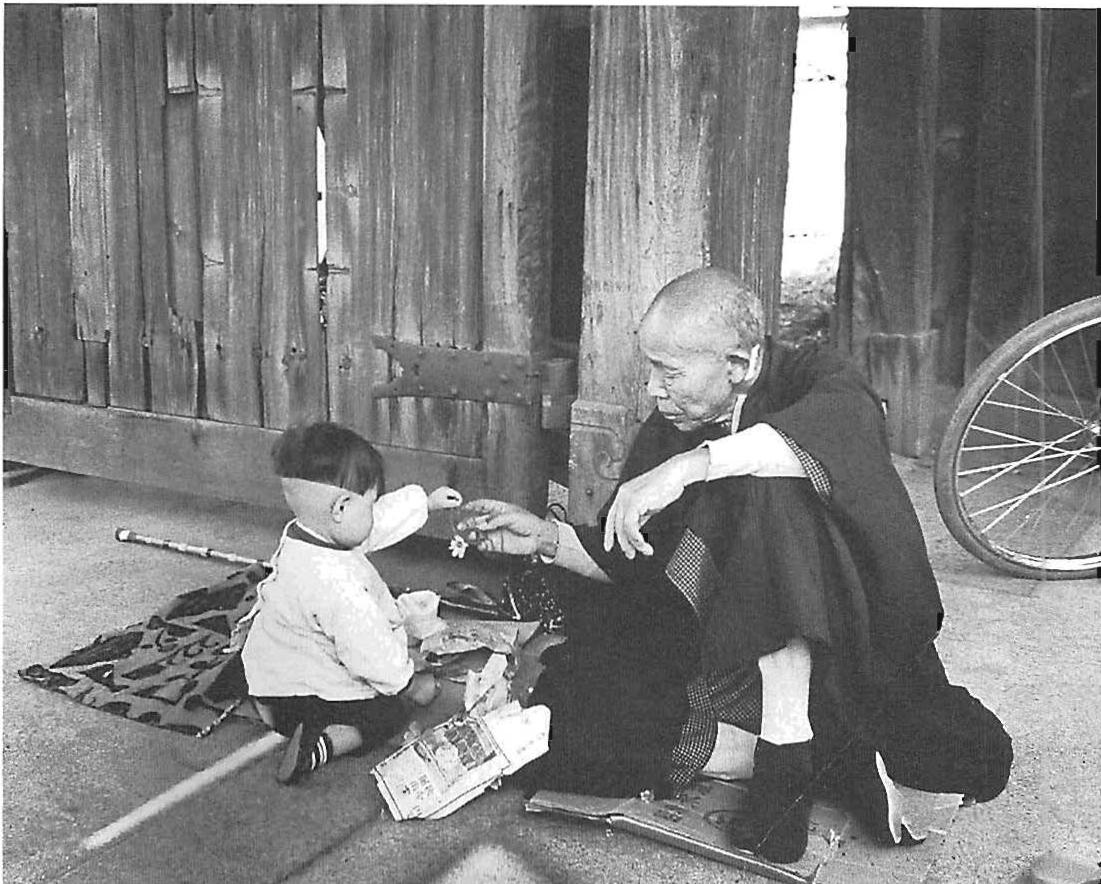

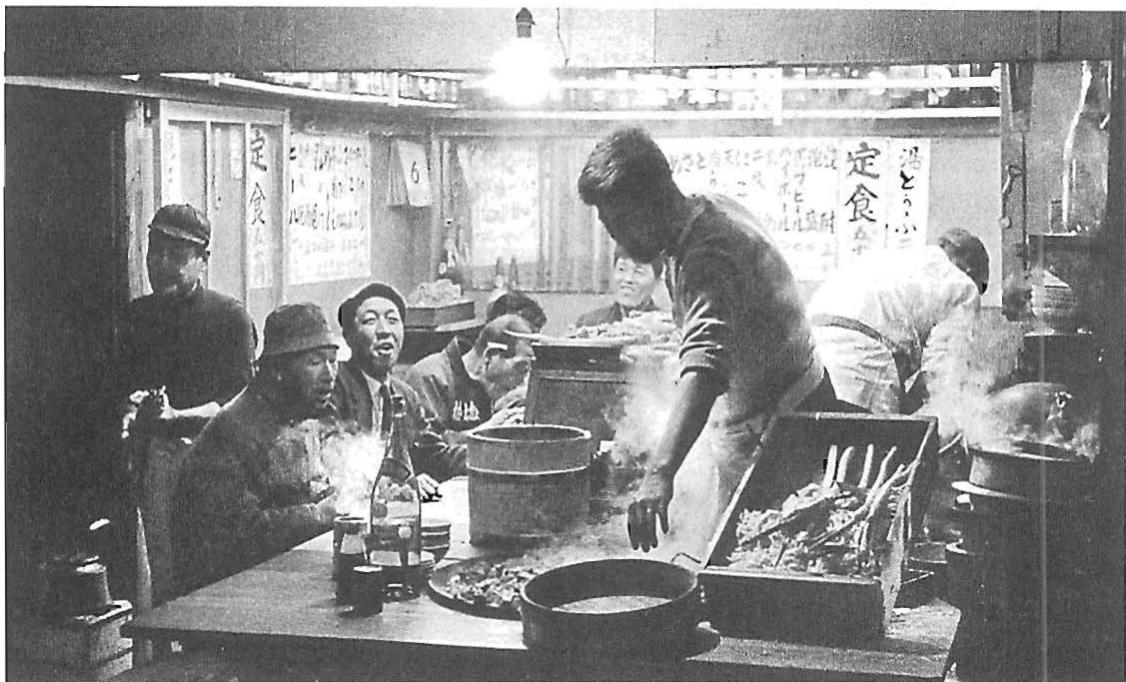

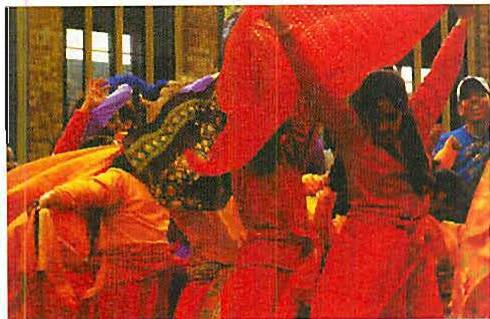

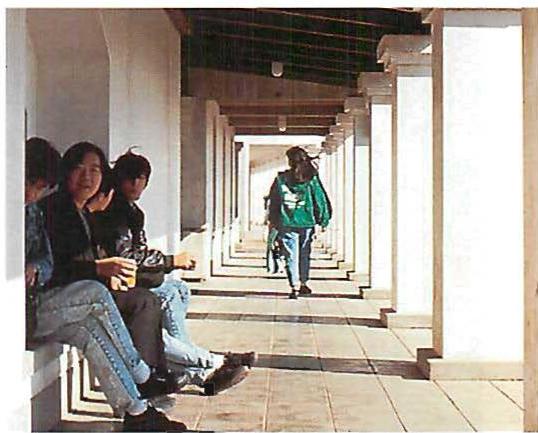

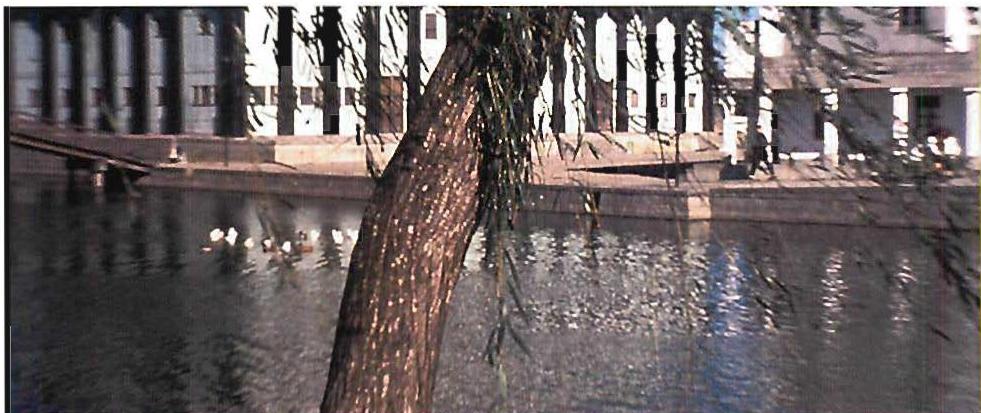

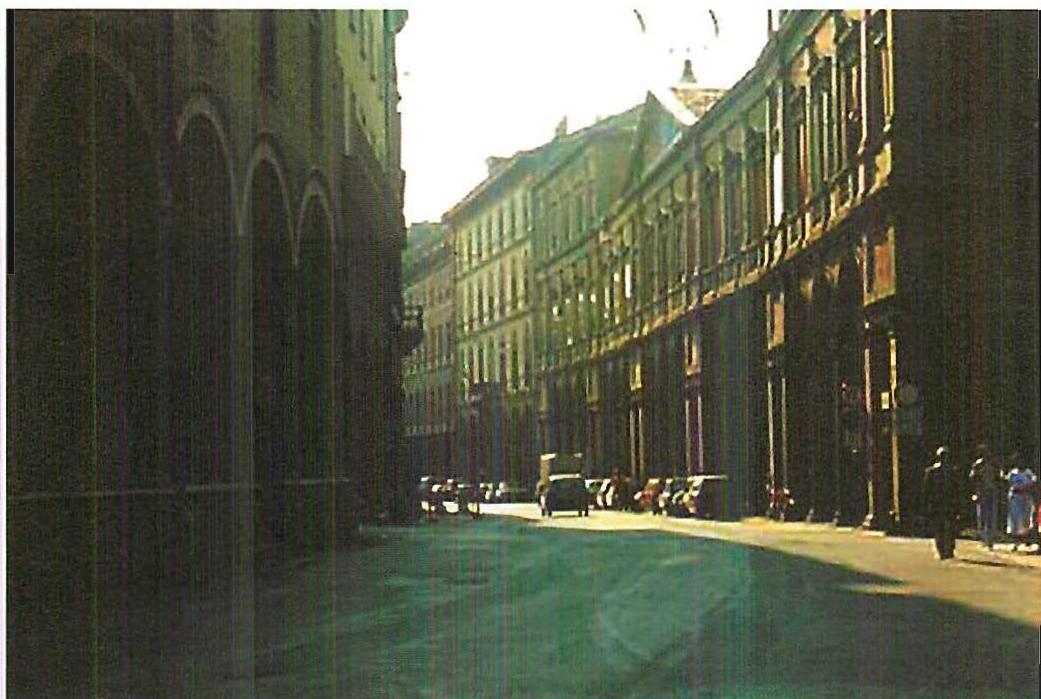

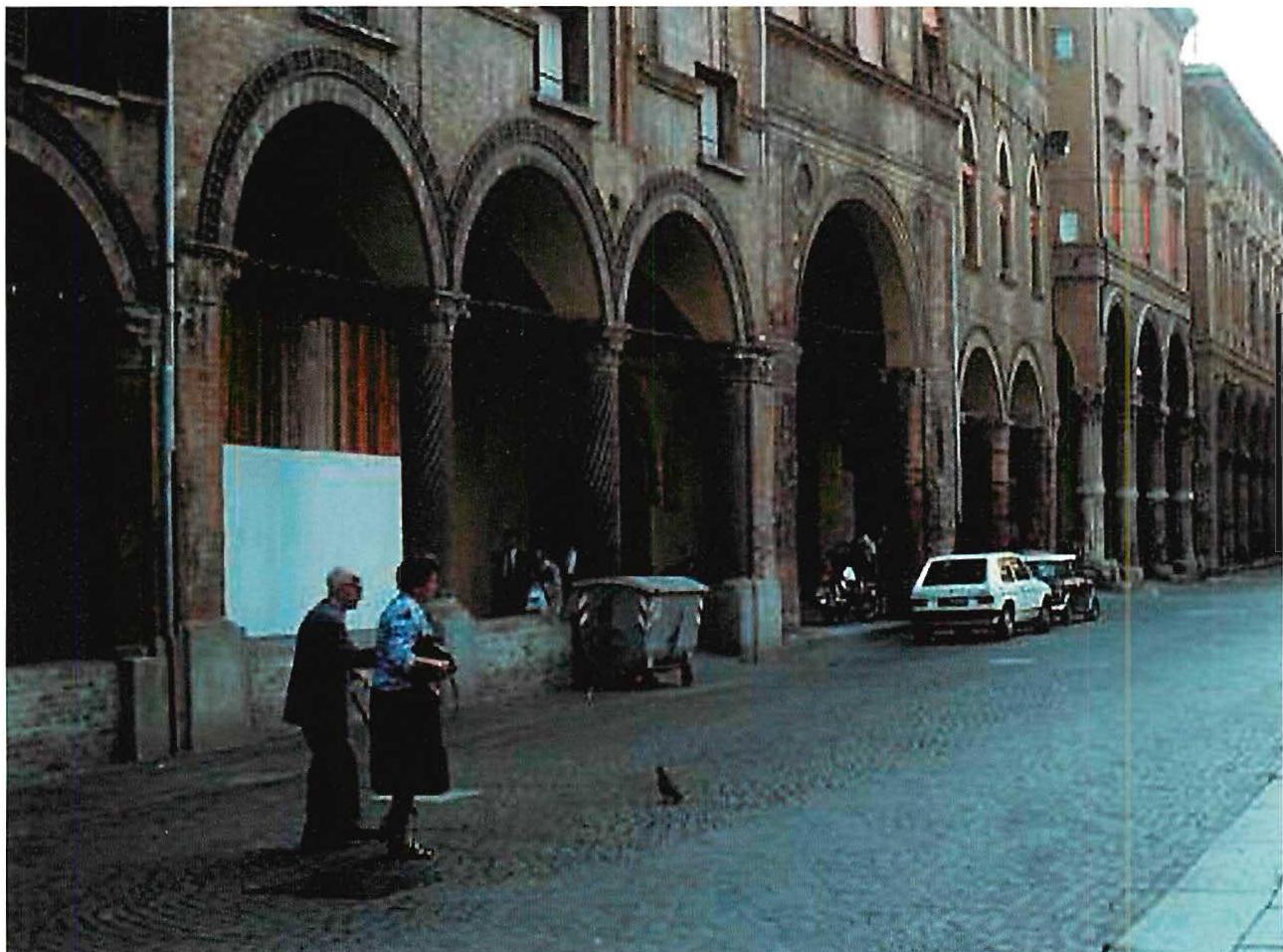

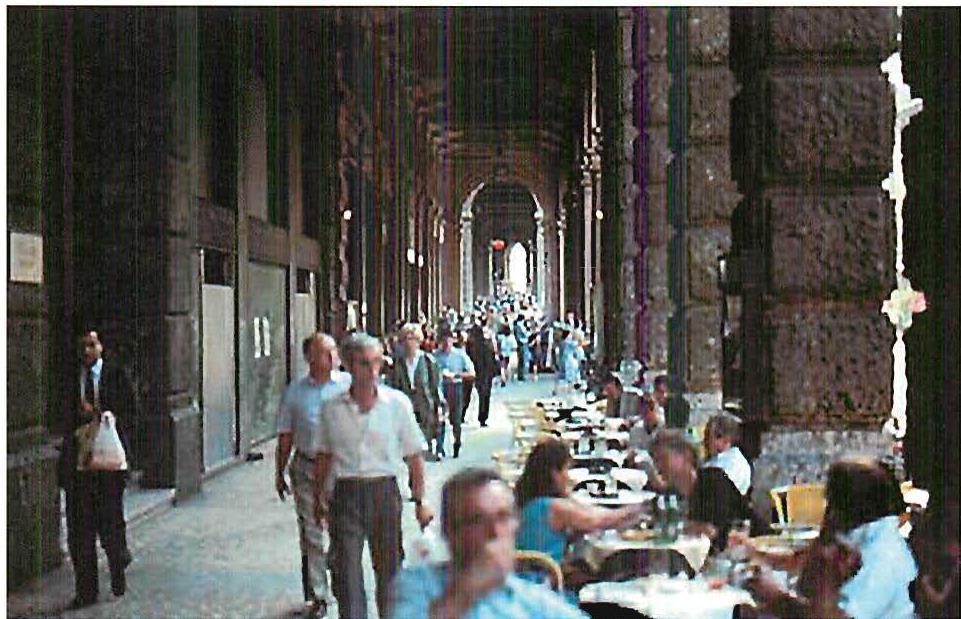

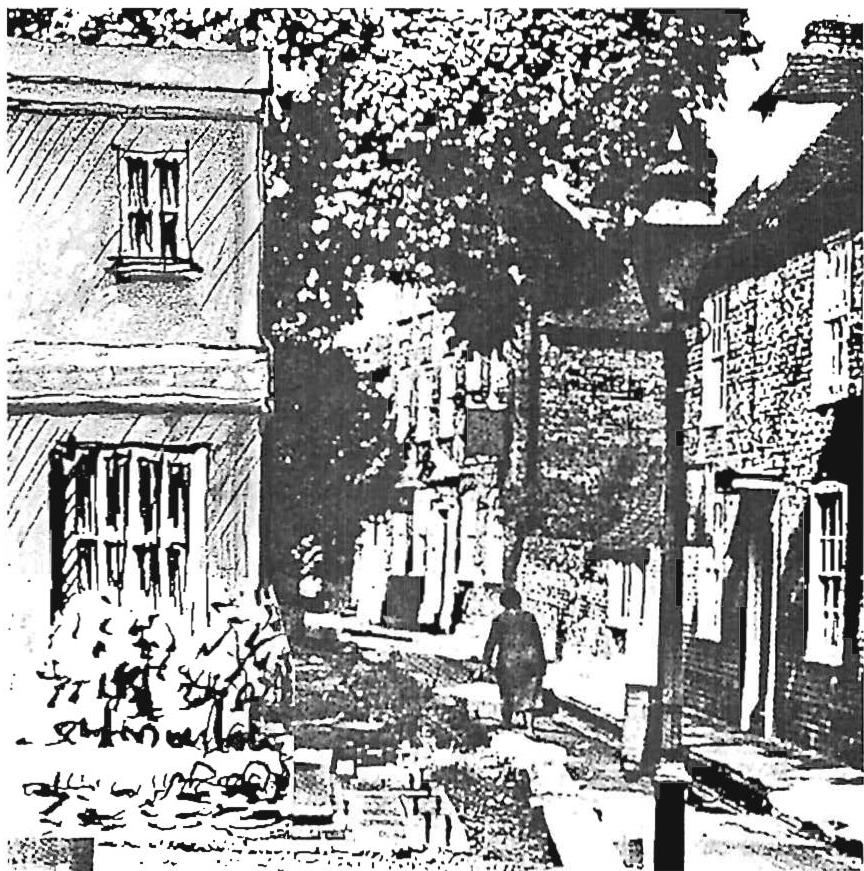

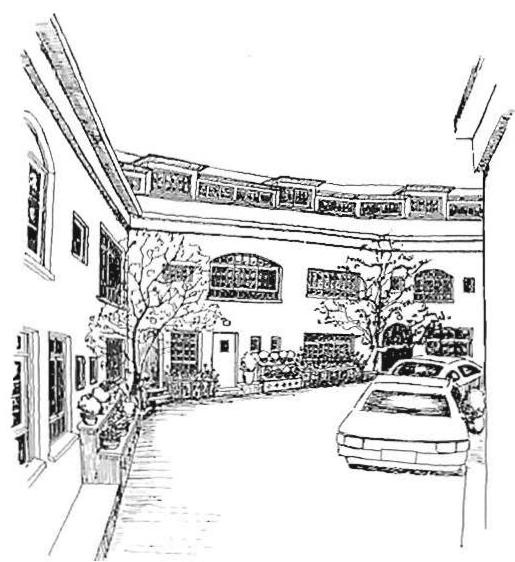

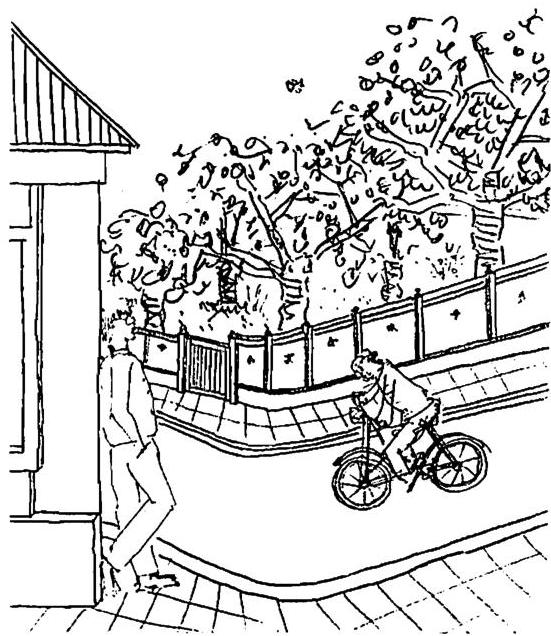

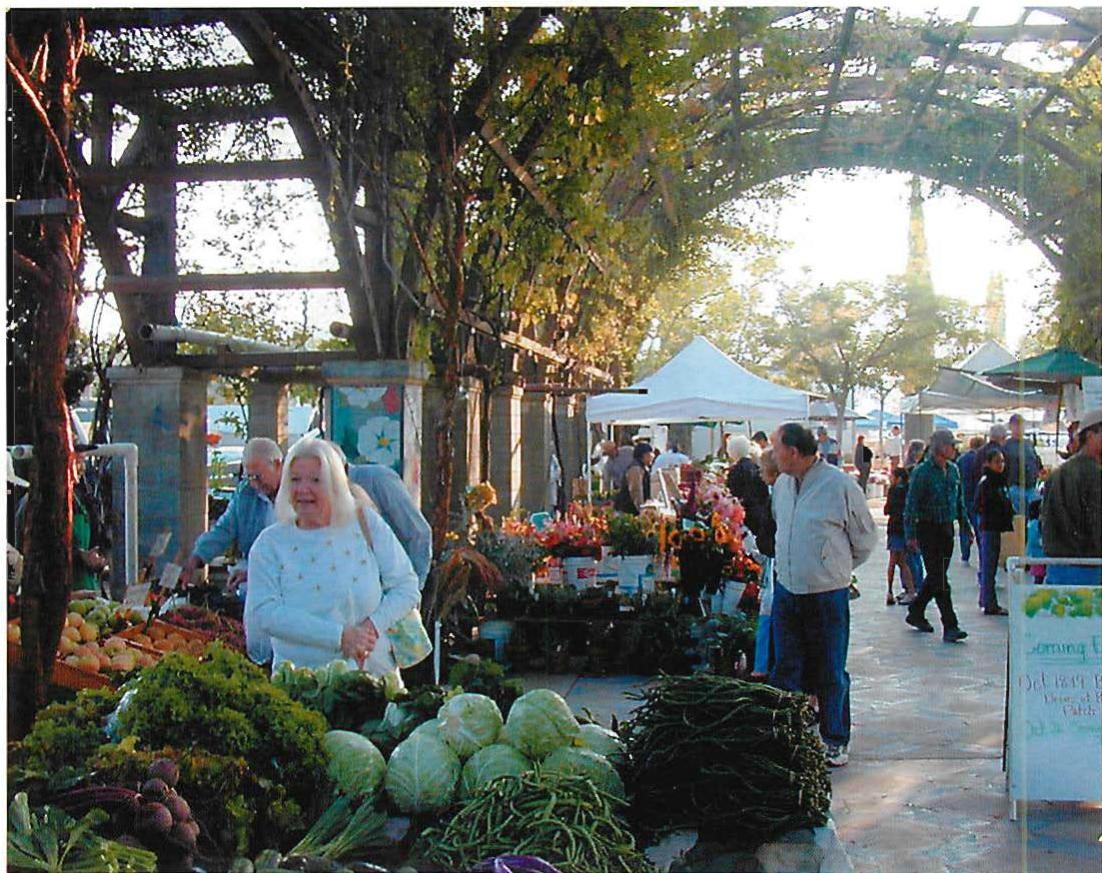

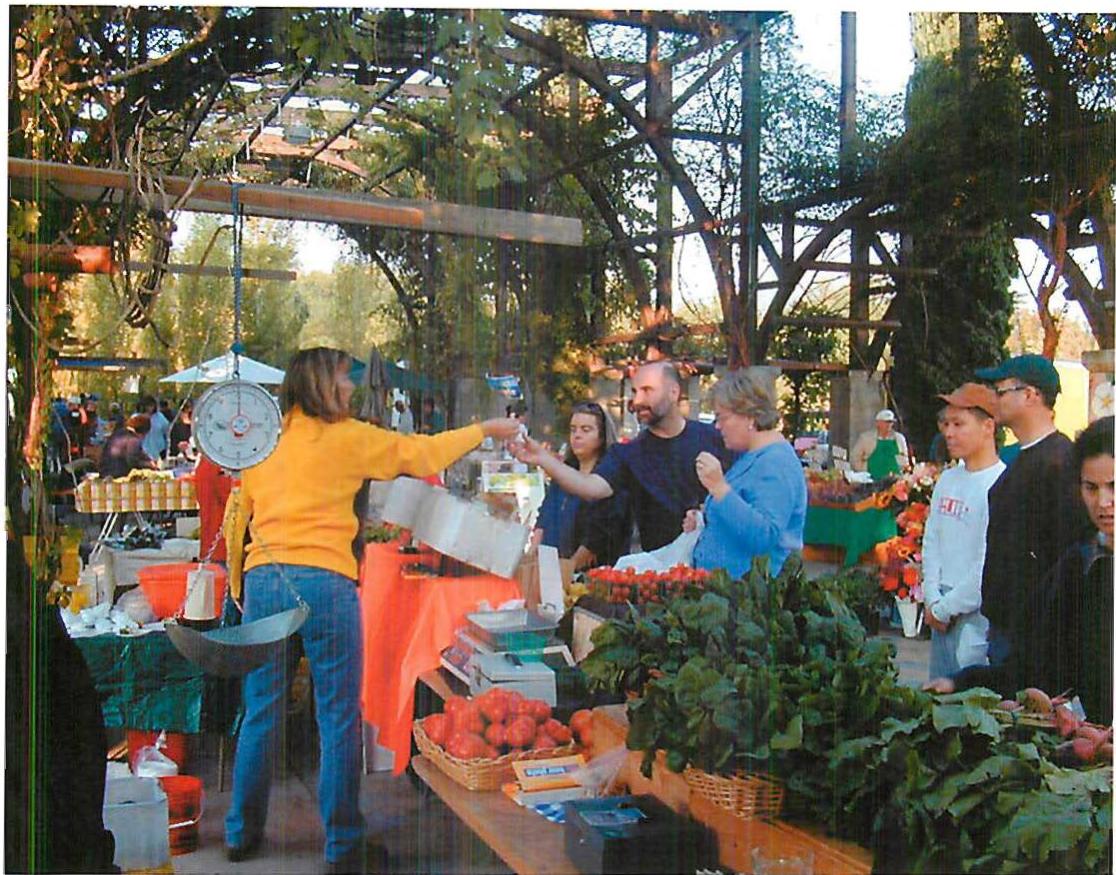

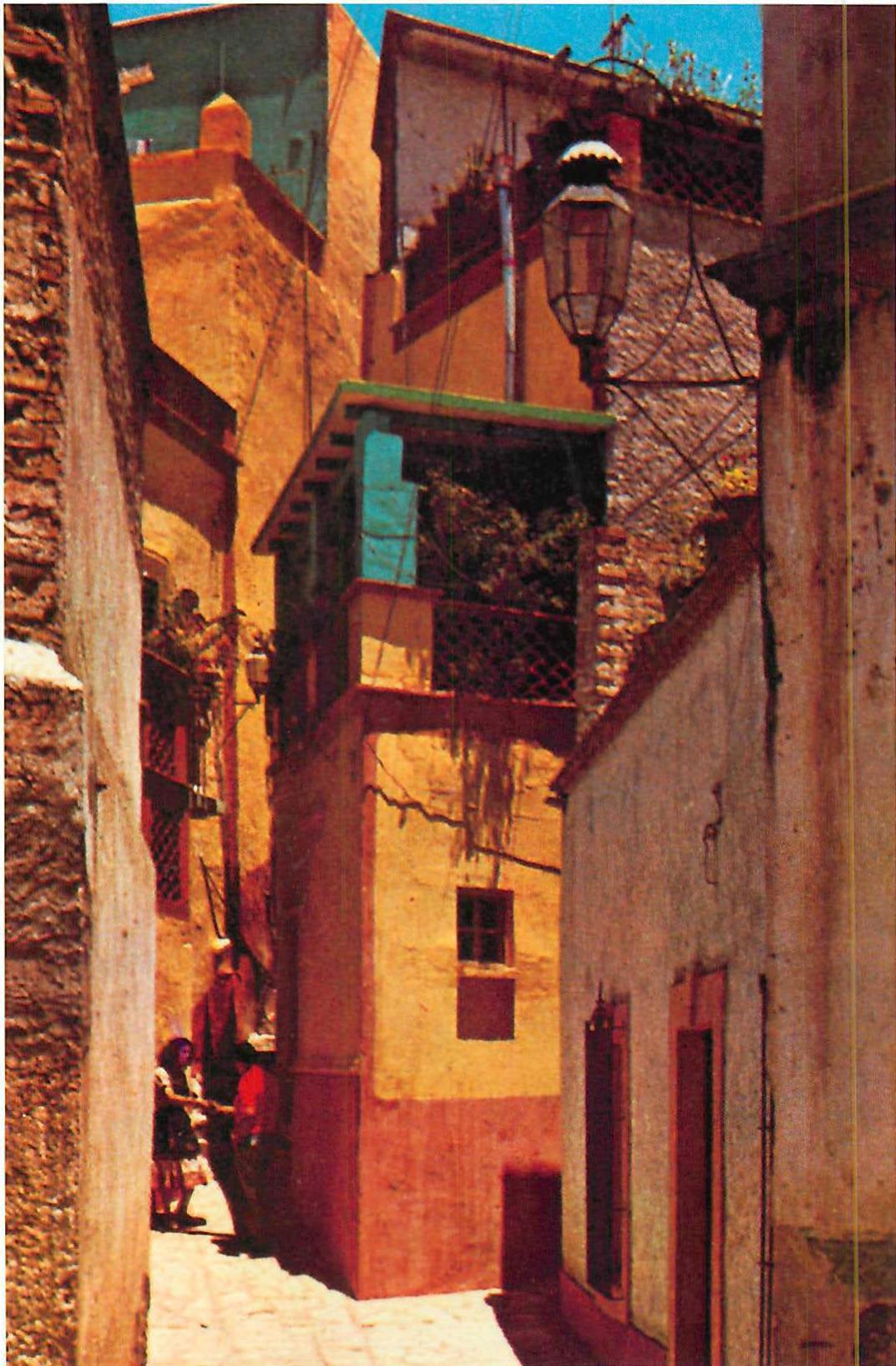

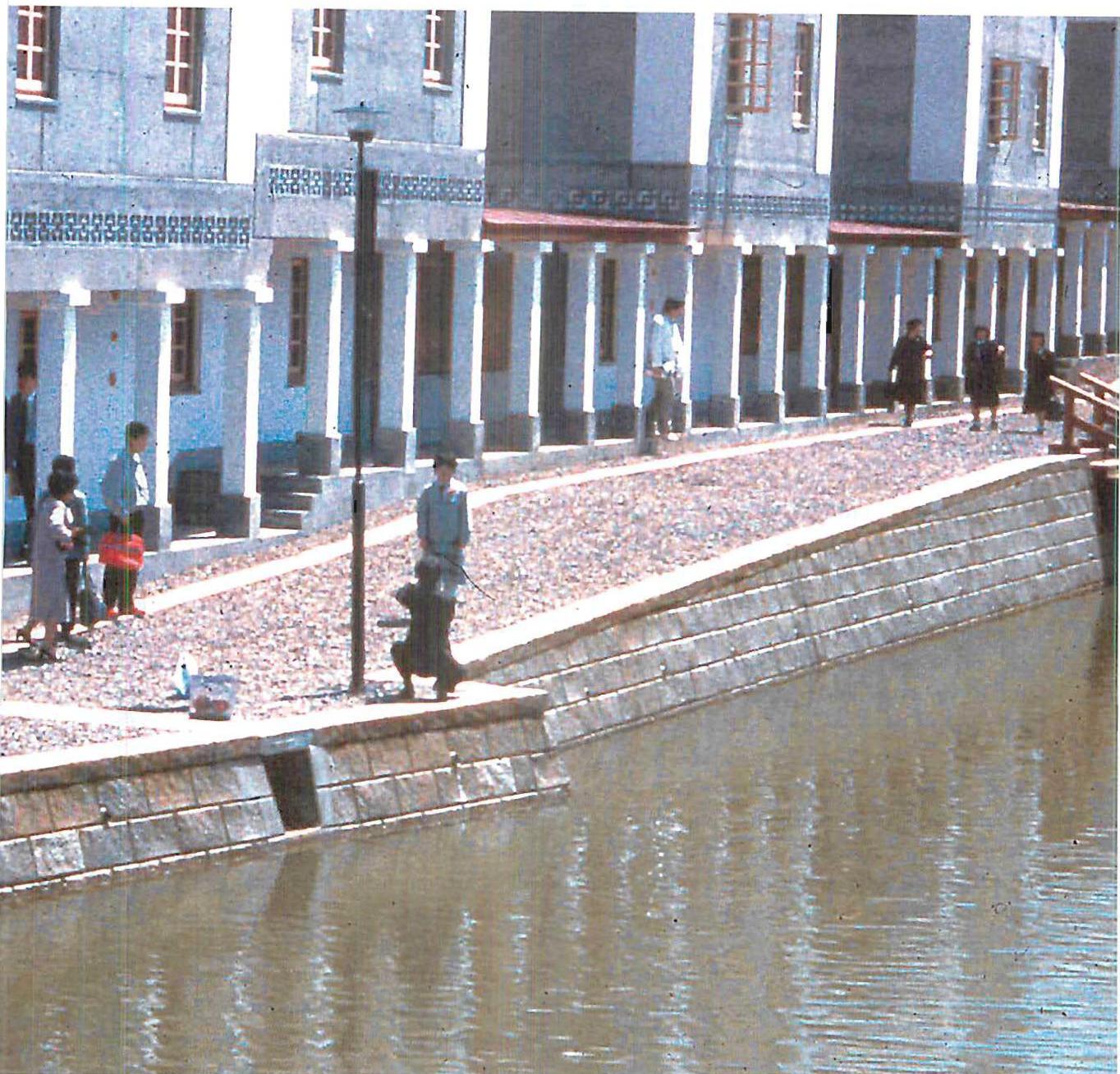

2 / THE LIVING ROOM OF SOCIETY

All my life I have been inspired by what happened in traditional society and marveled how much people all over the world knew about essential things. In traditional society, up until the onset of this century, the space that existed between buildings was like the living room of society. It was the place where people did things, got together, felt comfortable. In many traditional urban societies — I'm talking about days that are not too far away from our own time — people didn't even have enough room to entertain in their own houses. It was the natural thing for them to go out in public to entertain, not just go out and have fun as we do today, but something more ordinary; two or three people would go to the cafe or the pub in the same spirit and with the same ordinary feeling and intent that we have a friend over for a cup of coffee in the living room. And everyone felt comfortable about that, out there. The public land was the living room for everyone.

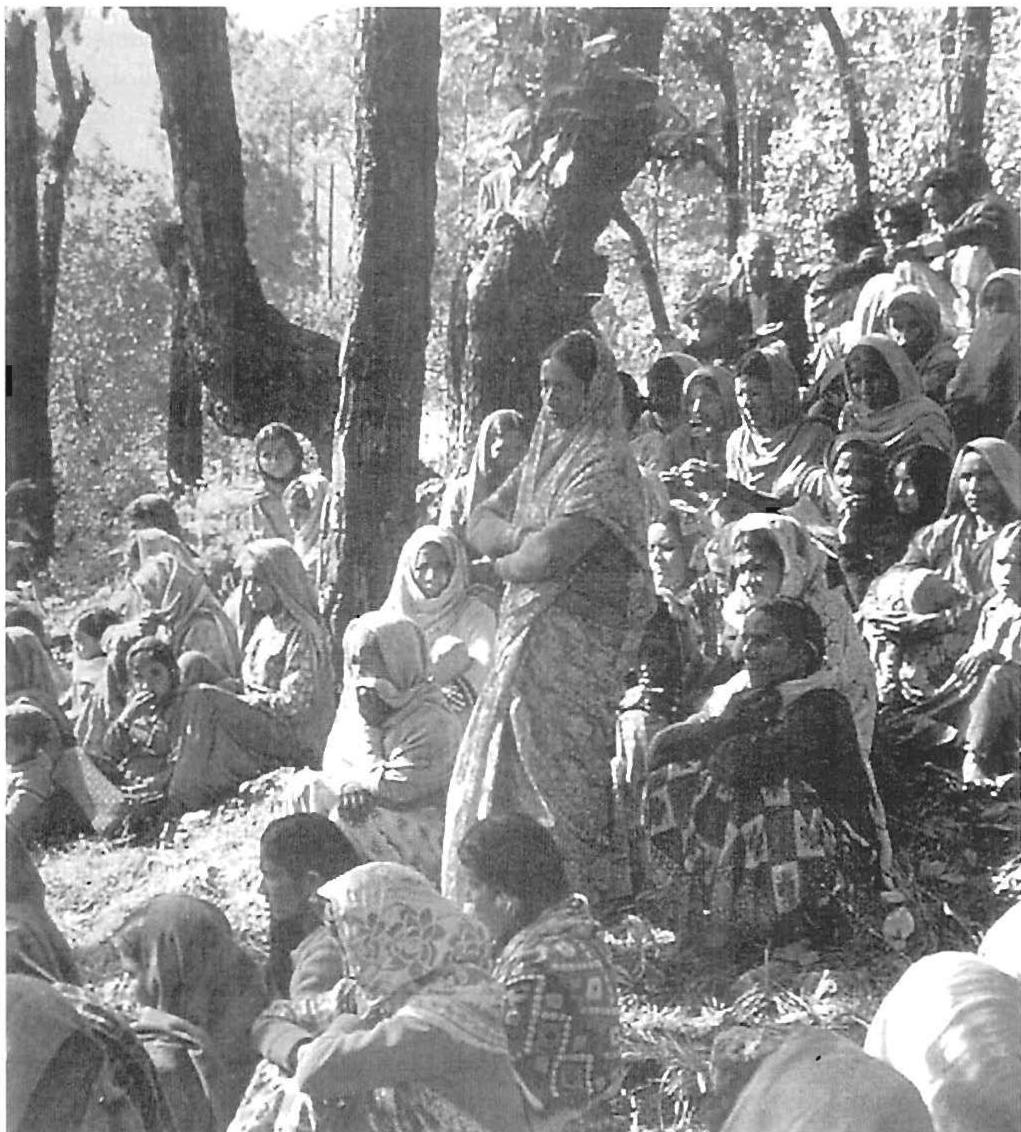

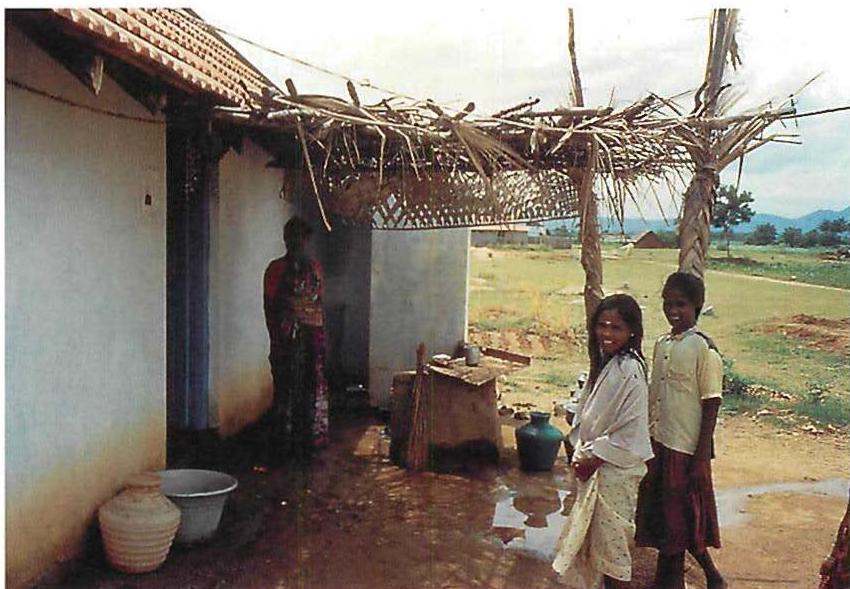

I lived in India at one point in my life, in a small village. The central space in that village

was a compound surrounded by mud huts. At night all the men pulled the cots out that were leaning up against the verandas of the houses, and we lined them up in a long row down the middle of the compound and then lay there smoking as the dusk came down, talked for a couple hours into the dark, and then went to sleep... got up in the morning and brushed our teeth... and out we went. That sense, in which the public space was actually the living room of society, was true in Italy, was true in China, was true in Africa. It has been true in every human society until the 20th century.

Where does Sakraji get the dignity and joy we see in the picture opposite? He gets it because he belongs, wholly, to this village, and it belongs to him. And how does he get this belonging? He gets it because he and his villagers control everything in their environment. Without that control, you have the situation depicted on pages 32-33.

In our century the loss of control and loss of belonging started with the car. The car of course is a wonderful thing. I, we, almost none of us, would willingly give up our ability to have cars and get what the car can get us because it creates this phenomenal kind of access to everyone and everything, which is so valuable. But at the same time during the last century, because of the car and trucks, nearly all the streets have been taken away from us. And for property reasons, too, as in the picture on page 36, even the common space that is provided for pedestrians, emotionally does not belong to us.

It sounds maybe a little exaggerated for me to say this so strongly, but in the Indian village it is very plain and ordinary, it's not some big fancy thing. In the Indian village, the public place belongs to the people that are moving through it. You can stay there, you can enjoy life when you're there, you can smell a flower or light a cigarette and not worry about the surgeon-general's rules. Just be there, talk to somebody.

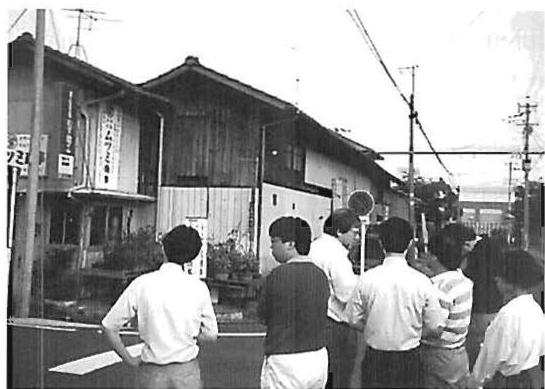

In 20th-century development—even in the best kind where communities and social agencies worked together for the common good—this is what got created. Again it was anonymous, again no belonging, again no useful public space being formed, again no expression of the individual or of the individual family. Twenty years later, this place will be just like the slum which it replaced, because there is no spiritual ownership.

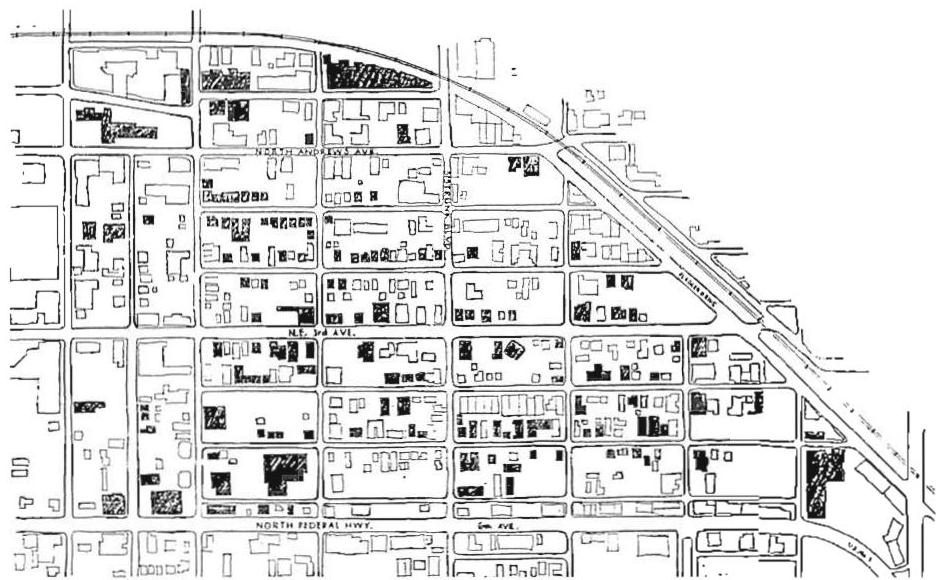

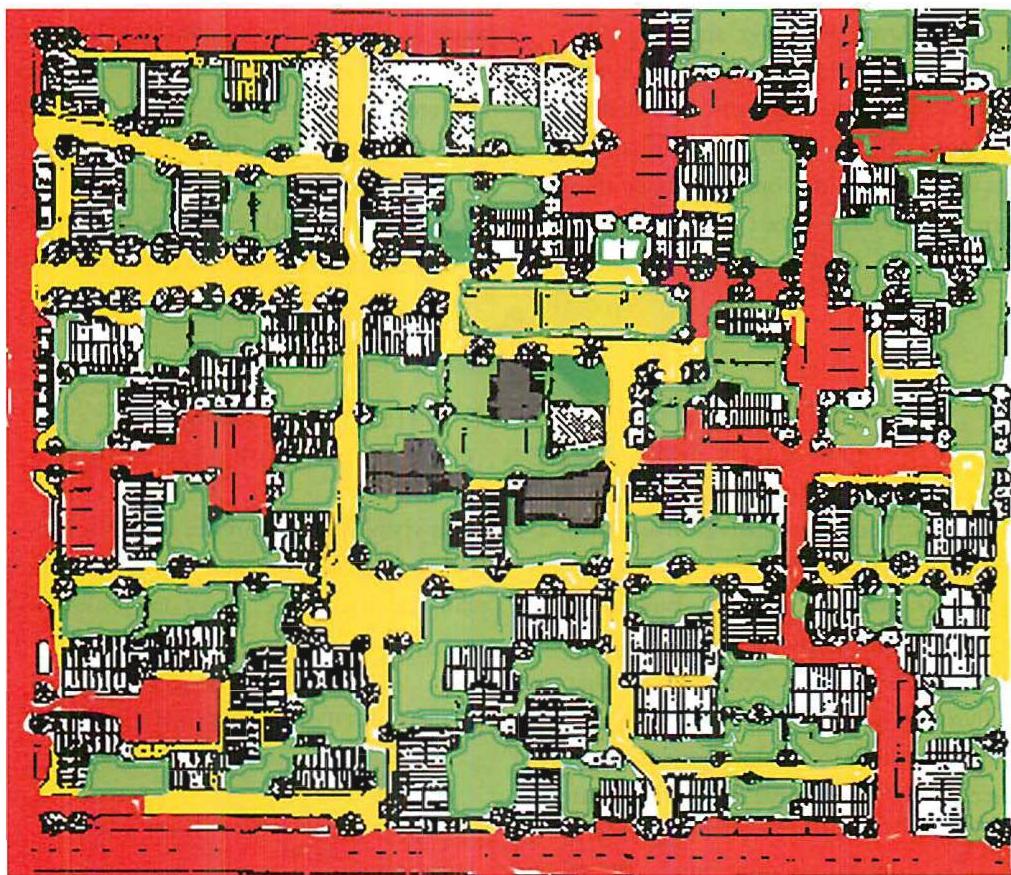

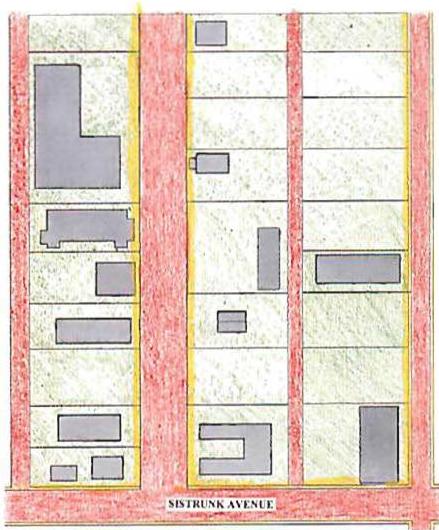

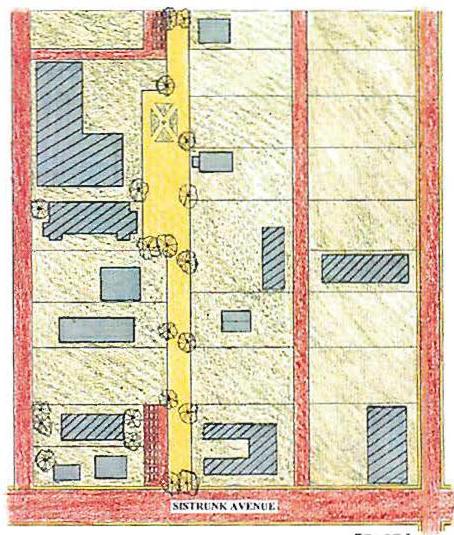

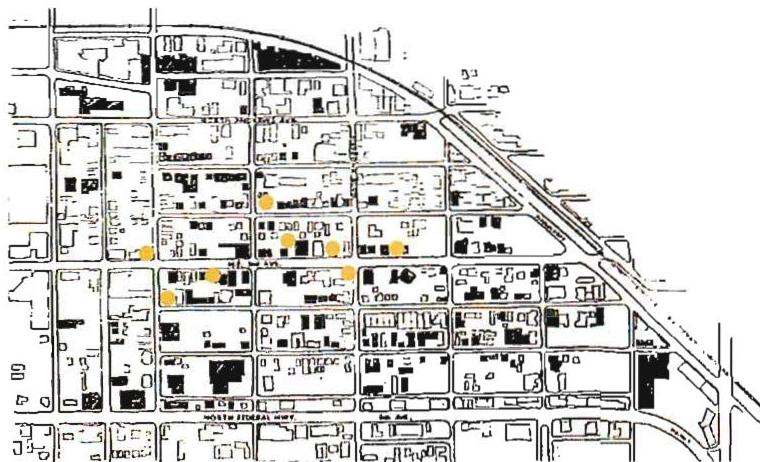

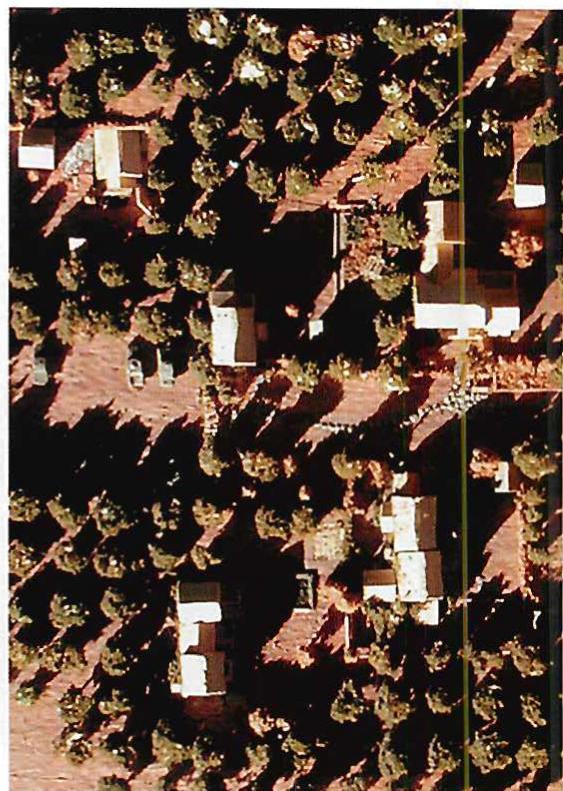

By comparison, let us look again at a typical development of the late 20th century. Look at this public housing project in Florida. You see the problem. With the parking spaces, very little space is actually usable. You may think this is a problem of density, that as density increases you just cannot handle that urban space in a fashion that can become useful. Historically that was never true. It does not have to do with density. It has to do with whether there is a general understanding by people who build, and who pay for buildings, that the public space needs to be made usable, every fifty feet a useful and beautiful place to be, and actually to be the living room of your society.

In a living structure for society, the vital importance of the public room is fundamental. The street is not a thing to drive through, but a series of spaces which are the places where you most want to be. But to get it in meaningful fashion, again, as in the Indian village, people need to be in control—in control of their individual space, and in control of the public space. Design alone cannot accomplish this. It needs a change in the way we make it possible for people to control the world around them.

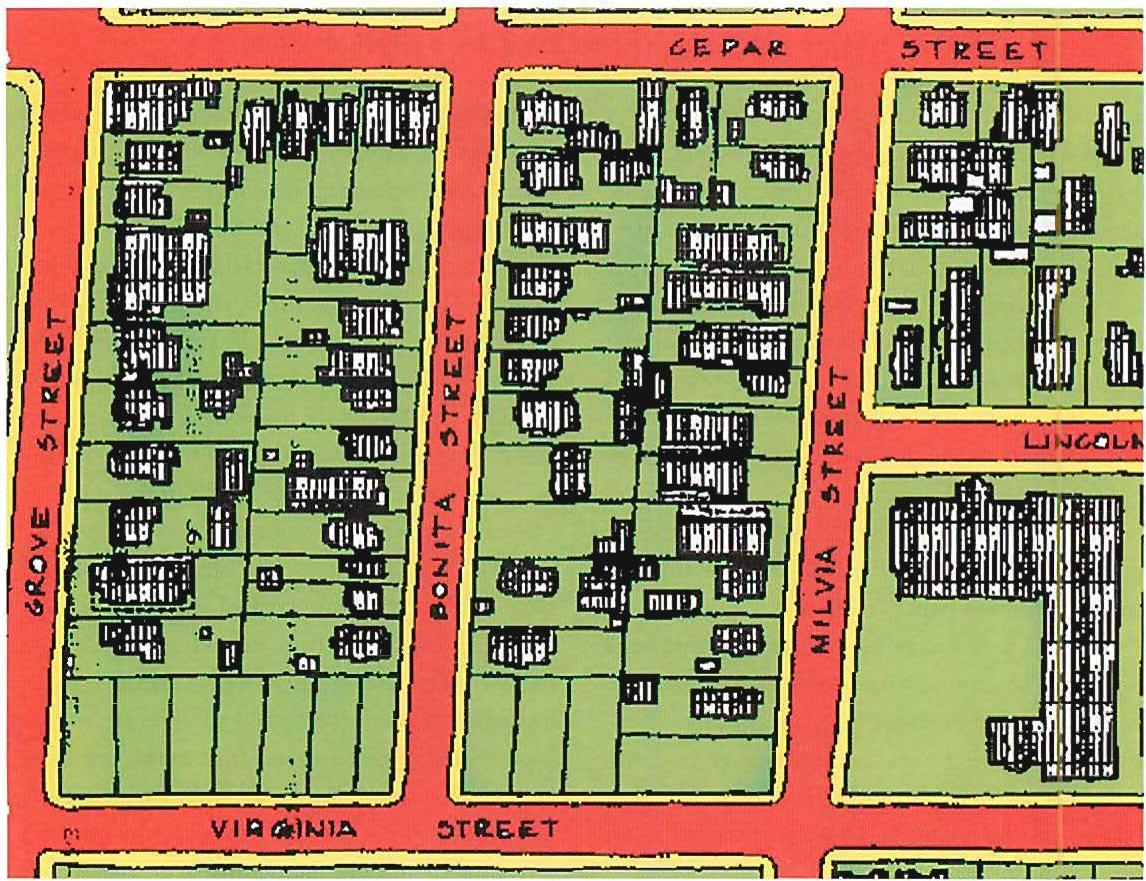

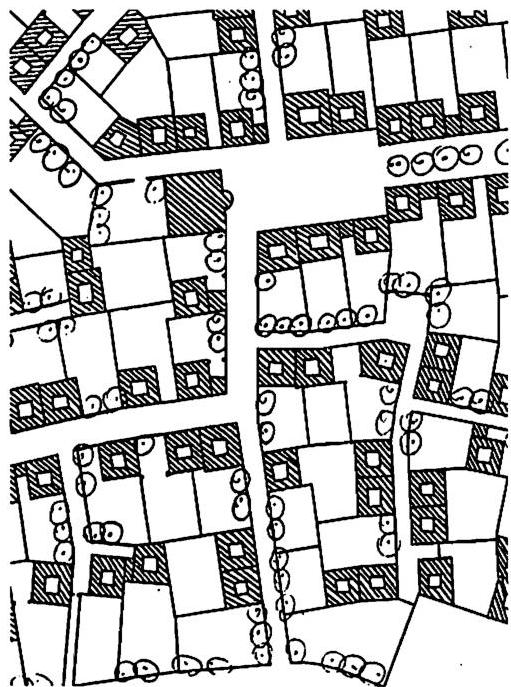

3 / THE UNIQUENESS OF INDIVIDUALS, FAMILIES, AND BUSINESSES

To get the individual adaptation which is essential for true belonging, we must have a process which allows the city to evolve so that it reflects each individual in his and her individuality. We must learn how to make a city where each one of us feels at home, whether it is yours, mine, his, hers. And once again this must be based on our individual true feeling, our true nature.

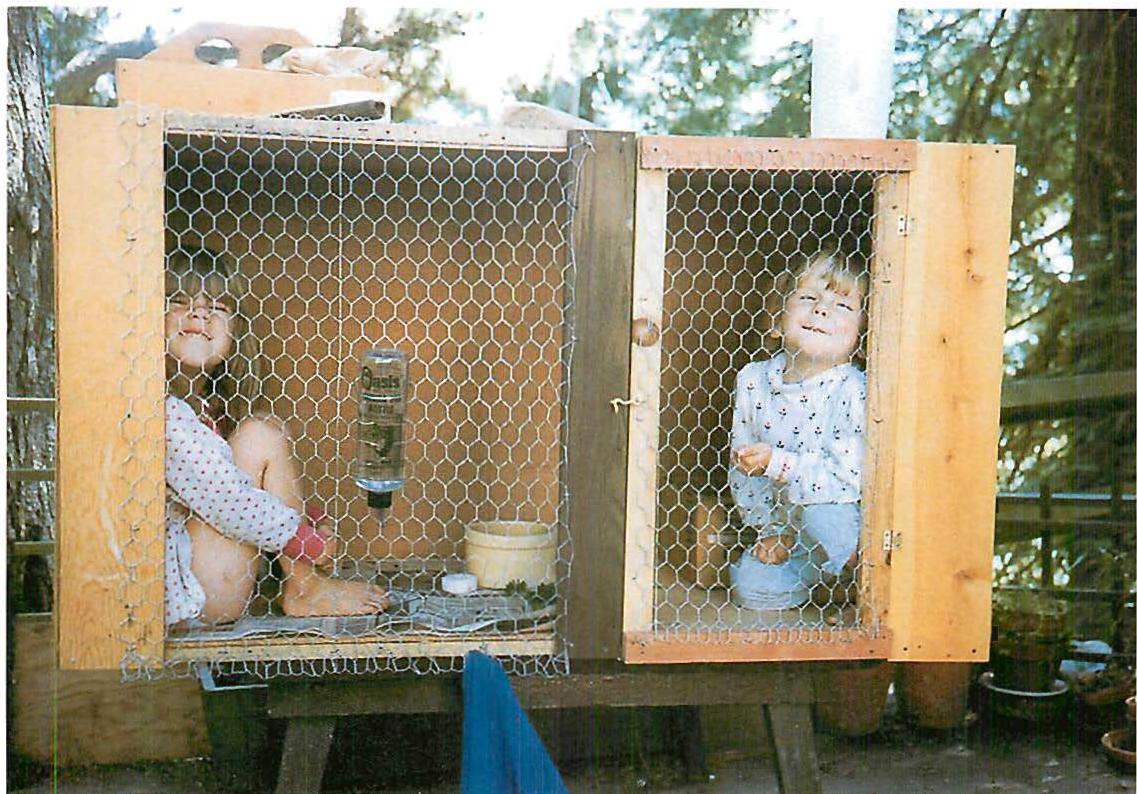

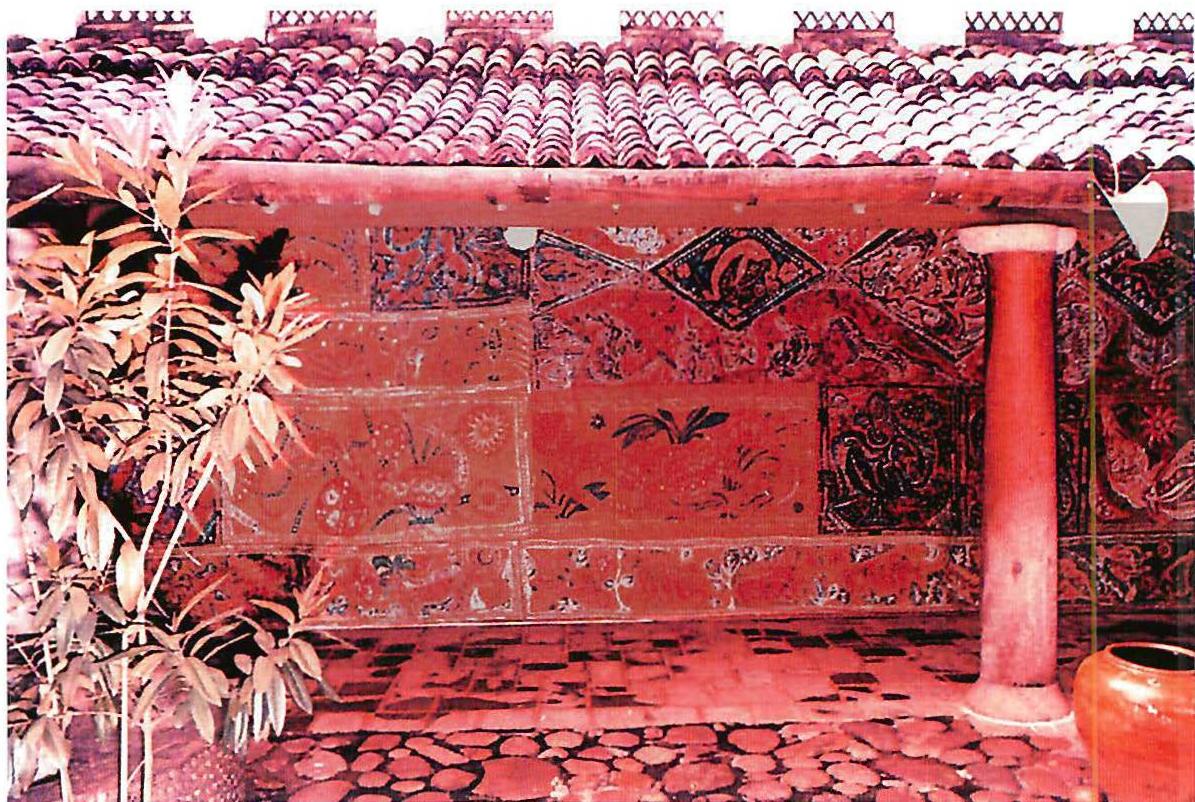

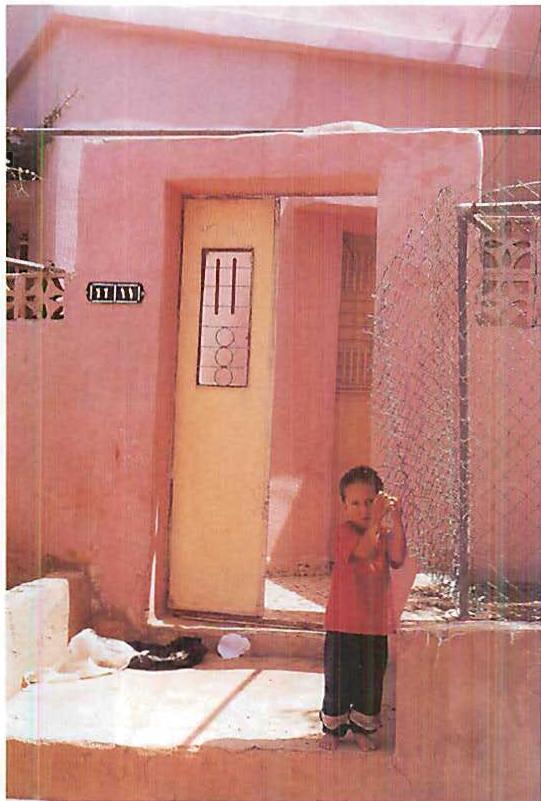

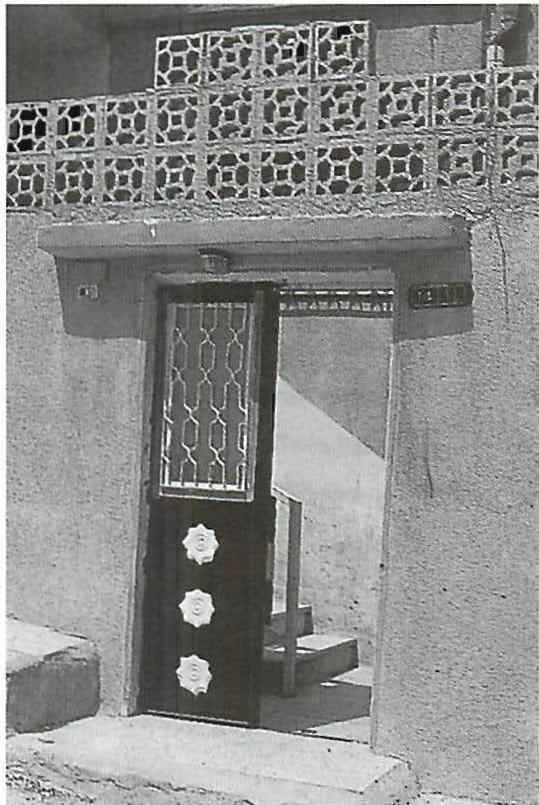

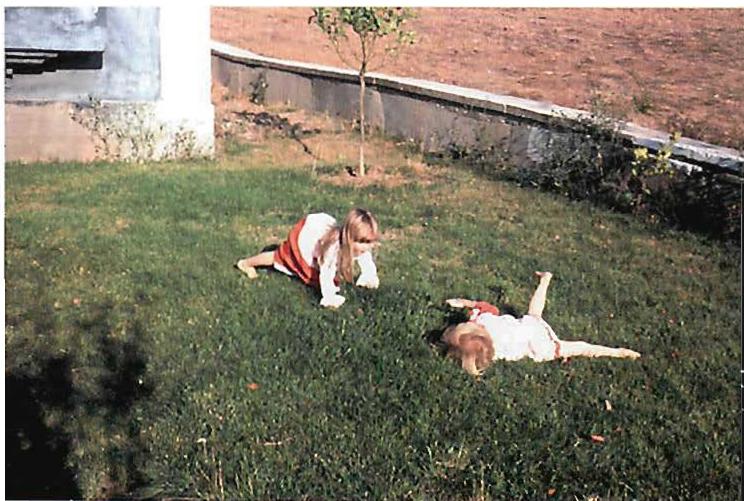

What this means is that we ask whether we experience it as ours, whether each bit of the city, of the neighborhood, each door, building, fence, garden, actually reflects human beings, reflects individuals, families, passion, reality. I was talking with somebody in a deteriorating neighborhood about this point, and she was immediately aware of this point. She said to me: "You know, even if somebody has a kind of patch, a bit of concrete in the front of their house, if it's a little scratchy bit of concrete that they did, it may not be perfect, but they know it, they love it, there's the paw print of the cat in it. It doesn't matter that it isn't perfect. What matters is that it has been done by somebody one Saturday afternoon and we see the trace of that imperfect person there."

Our lives work when we have that kind of intimate personal relationship to the environment. It is there of our making. Or it is there from the making of other individual human beings, we can recognize the human touch of it. It makes us feel something. It is ordinary. It isn't fancy, it isn't glitzy, it just makes you feel whole and comfortable.

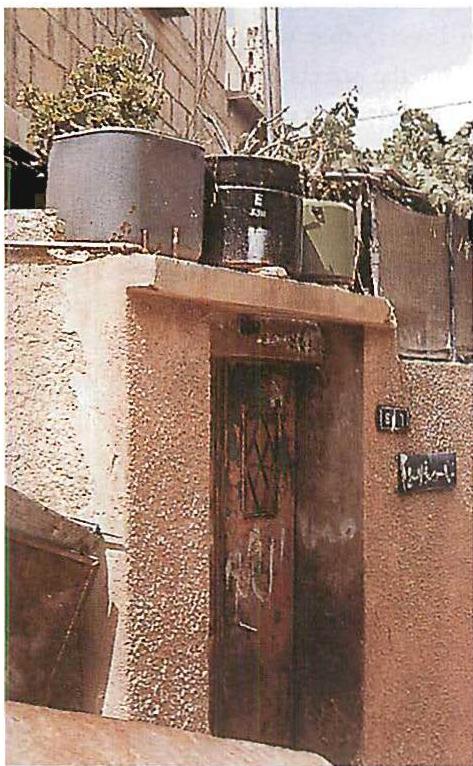

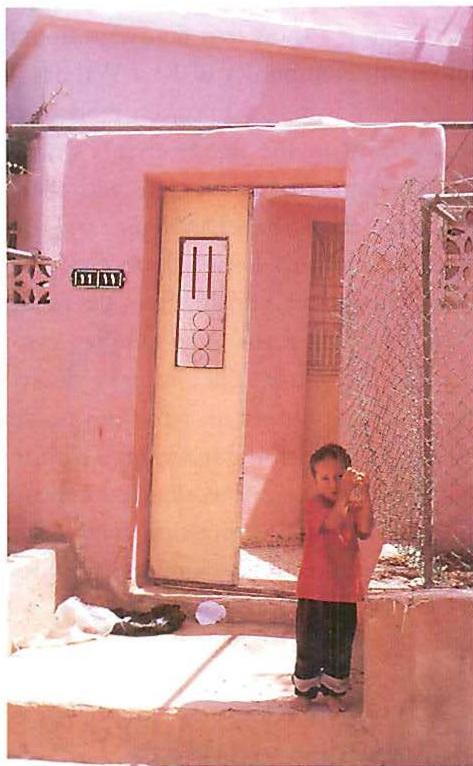

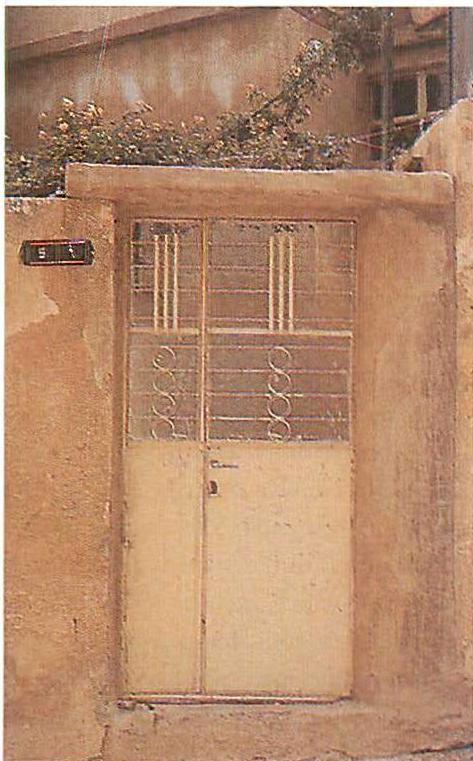

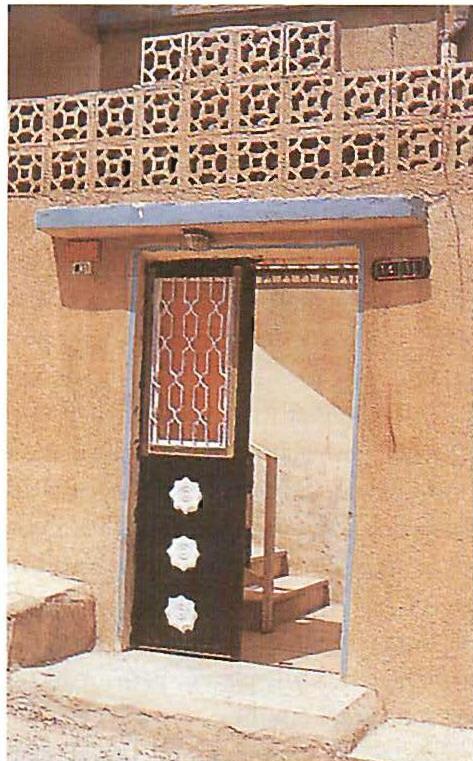

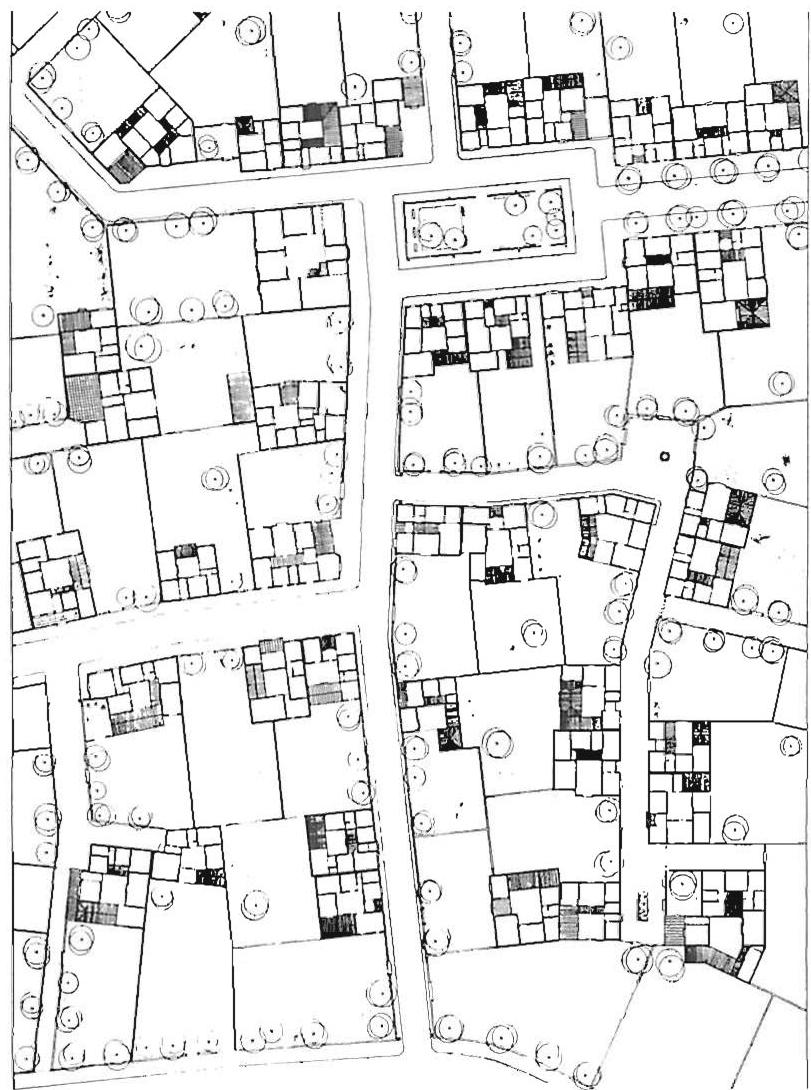

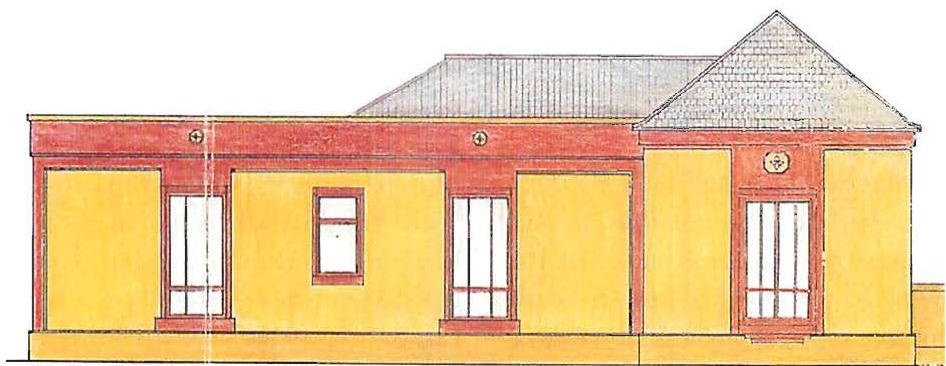

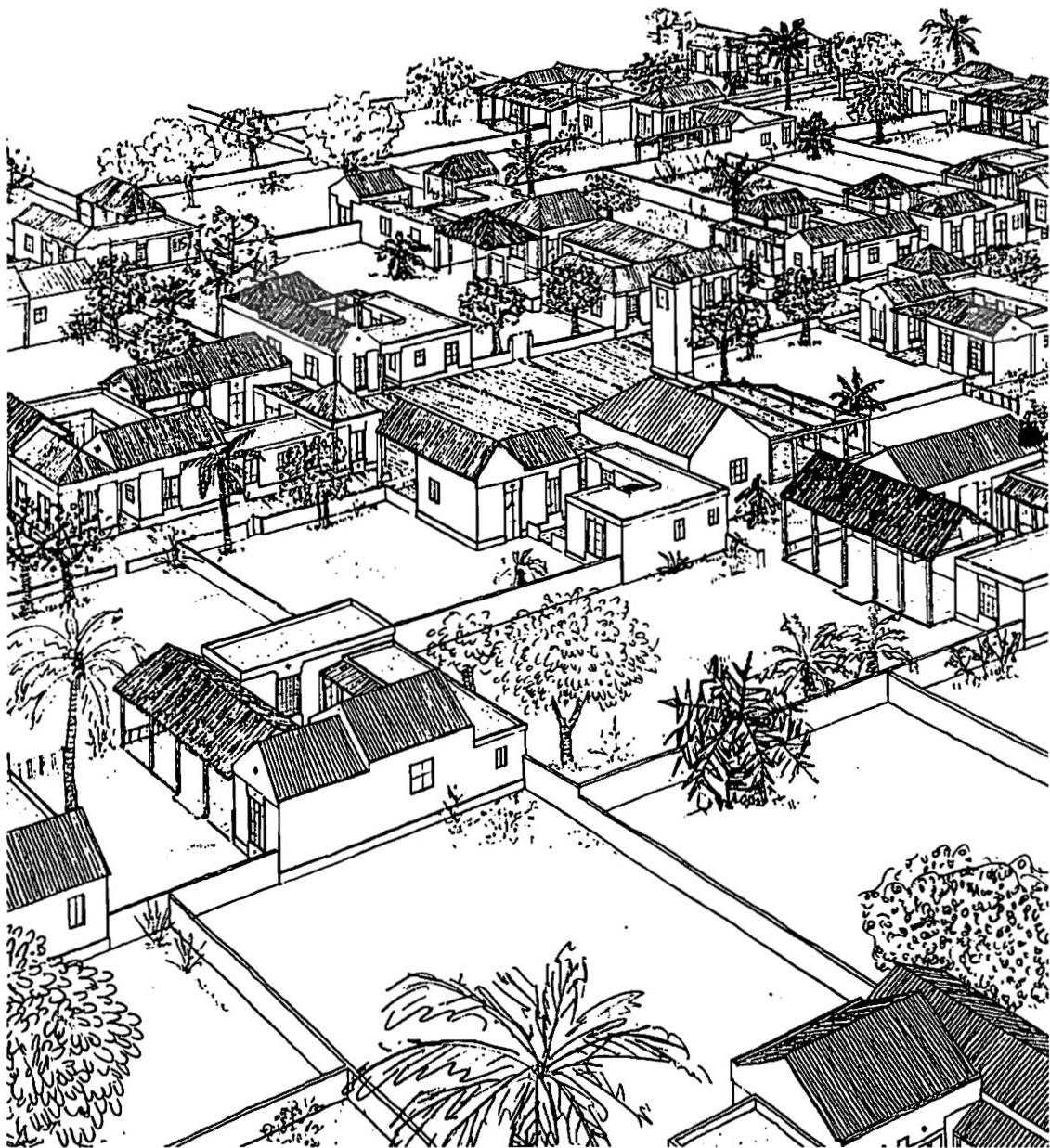

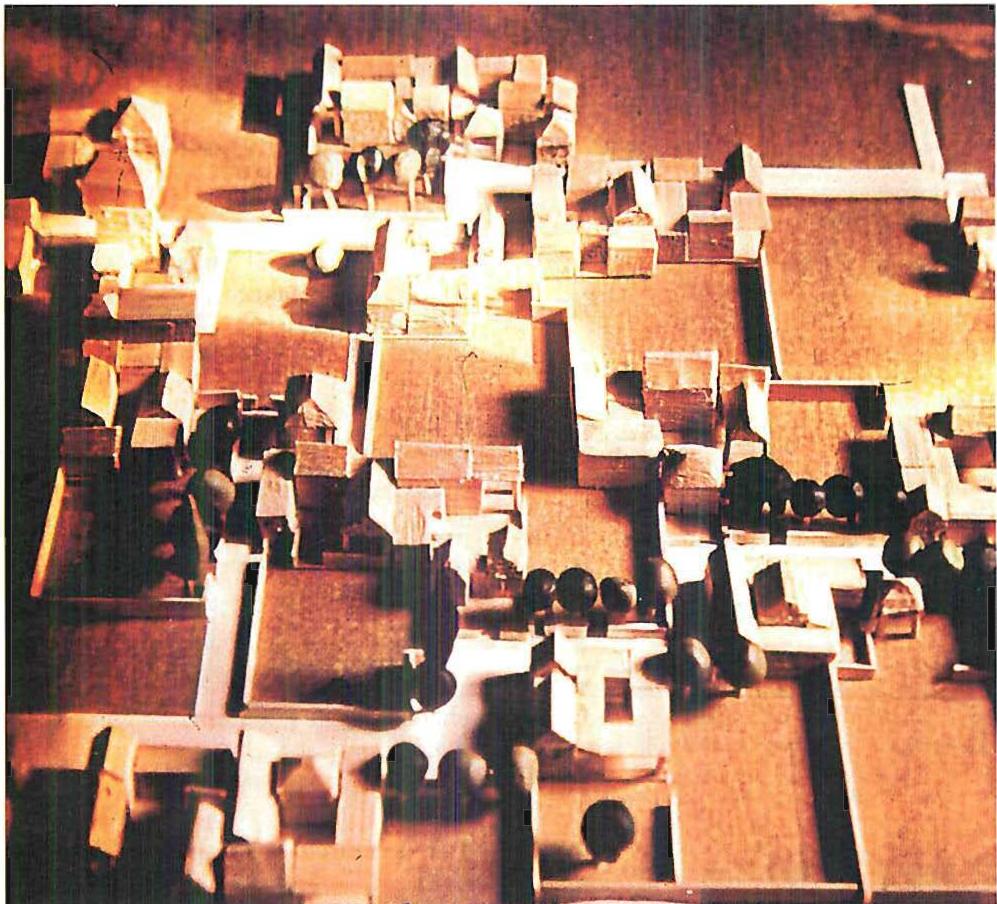

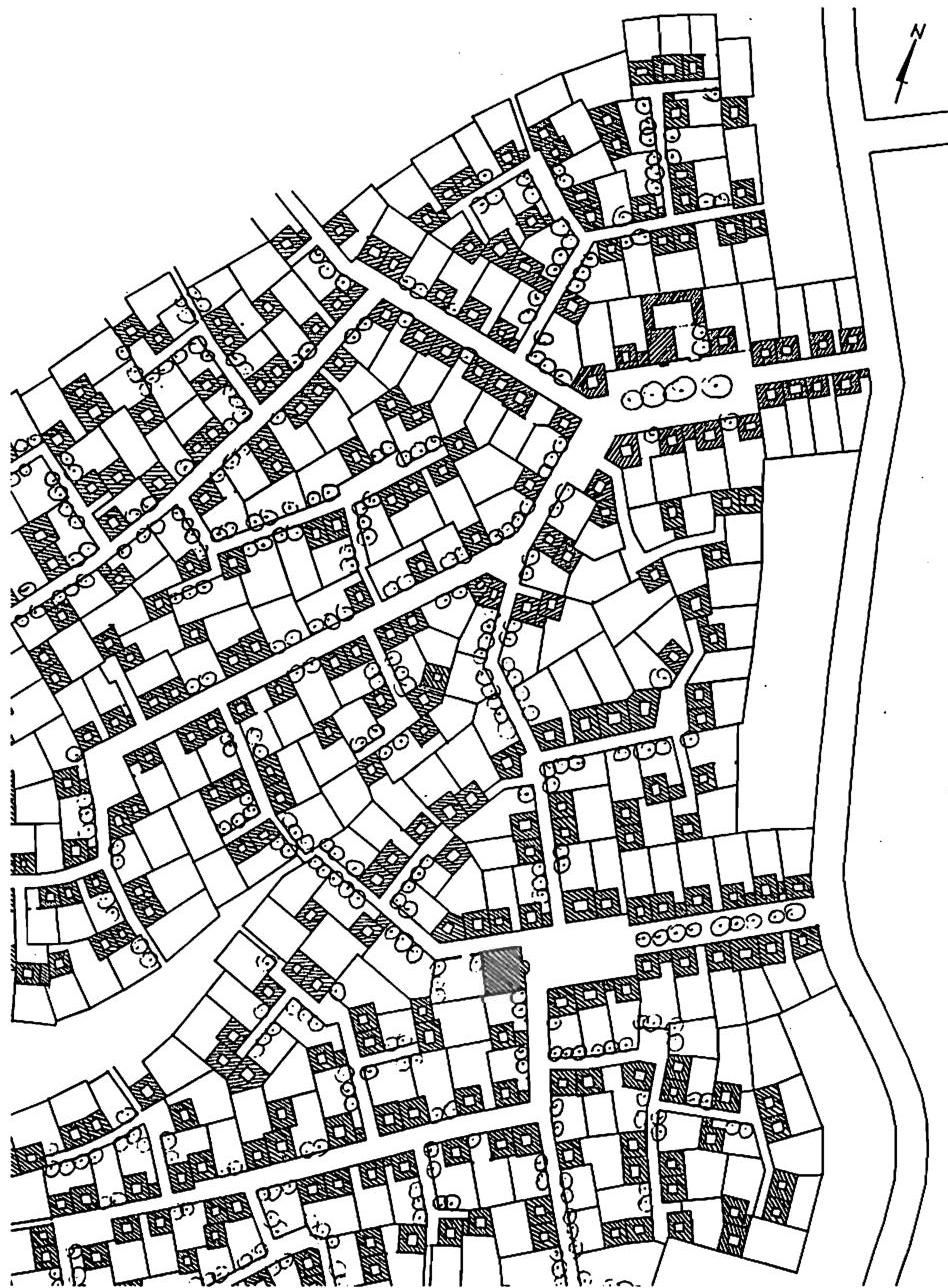

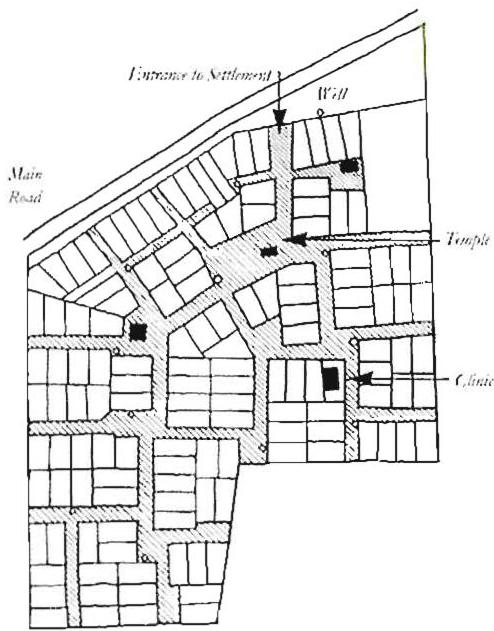

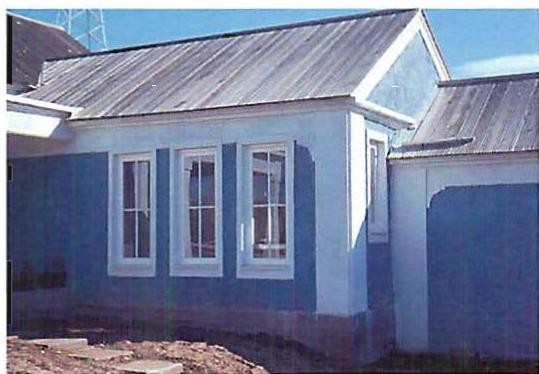

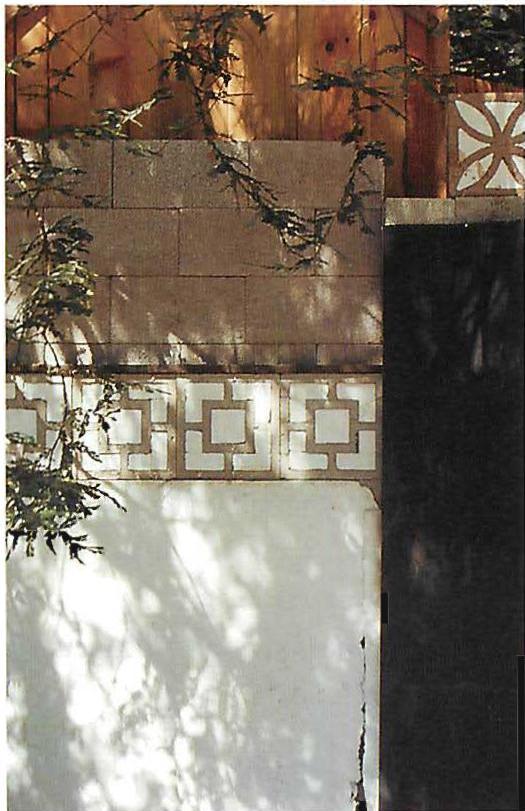

On page 37 I show four doorways from the recently built community of East Wahdat, Jordan. This is a wonderful project, modern construction, built in the last few years by public planners in Amman, Jordan. Here, with the simplest means, the Urban Development Department of Amman has been able to encourage a true unfolding process arising from the residents and families and owners. The families, not the agency, are in control. The ordinary variety of doorways is a testament to what can be done.

It has to do with the individual, with individuality, with the private world, the lovely world of individual people, expressing themselves in their funny, sad, intimate, imperfection, living their lives so that we see the imprint of those lives on the streets and in the neighborhood.

The private or individual space which is created by money, in today's society, is rarely making or fostering belonging. It creates ostentatious things, houses which express wealth and idiosyncracy, individuality for its own sake, the appearance of uniqueness. That is an immensely different thing. That is as far from true belonging as the sterile slums of the low-budget profit-hungry developer.

True belonging—true life—occurs when a penetration of the real into the fabric of the world occurs. This is far simpler. It is almost the very simplest thing a human being needs.

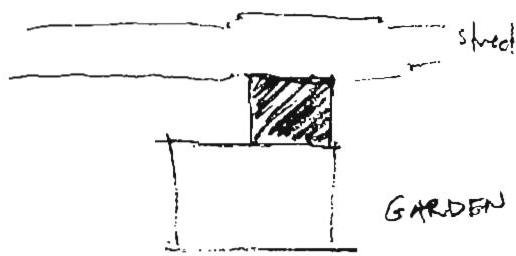

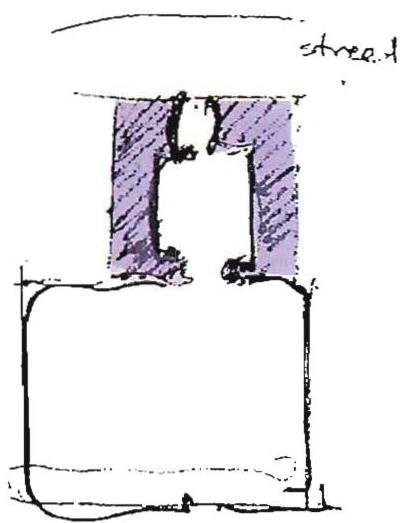

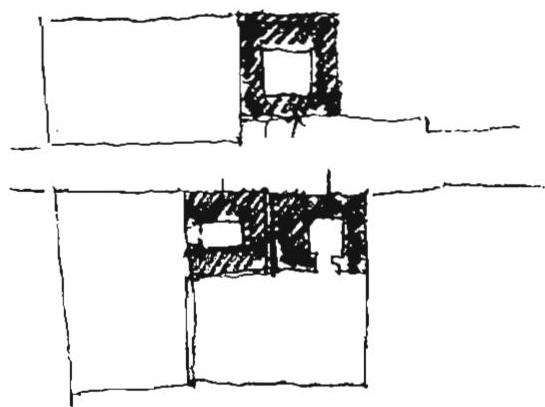

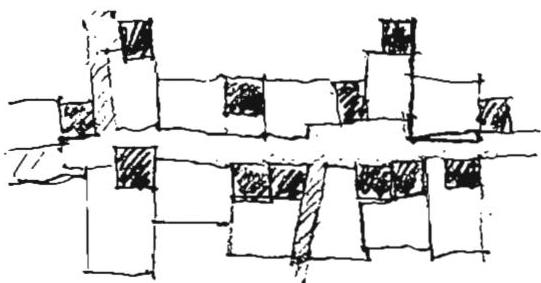

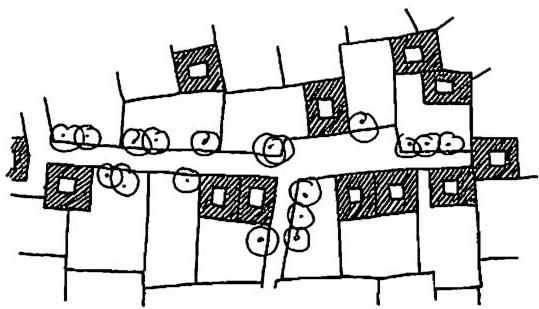

4 / INTERLOCK OF PRIVATE AND PUBLIC, AND CONTINUOUS SPATIAL TOUCHING OF THE TWO

To have true belonging, it is not enough to have uniqueness in the private realm and a living room in the public realm. The two must interlock. Each must touch the other continuously. Then the two can work effectively to complement each other.